GMRC Review: Powers by Ursula K. Le Guin

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, has gotten his January GMRC review in just under the wire. He’s an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, has gotten his January GMRC review in just under the wire. He’s an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com.

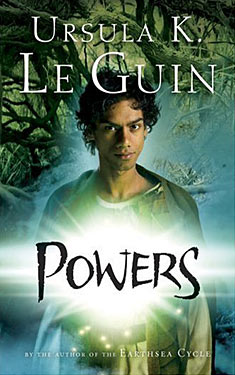

Powers is the third book in The Annals of the Western Shore, a YA series, with Gifts and Voices preceding it, and the only one that can be read as a stand-alone novel (hence my review for the GMRC, although Voices is to me the more accomplished and solid book of the series). However, the ending will be much more meaningful if all three were read in sequence. The books are loosly connected by a couple of characters, Orrec and Gry – we meet them as children in Gifts, and finally as adults in the final chapter of Powers. The seperate stories are set in geographically dispersed areas of the Western Shore and concern characters with different magical abilities, or gifts. The gifts are what make the families of the Uplands different, and even feared as witches by Lowlanders.

Powers is the third book in The Annals of the Western Shore, a YA series, with Gifts and Voices preceding it, and the only one that can be read as a stand-alone novel (hence my review for the GMRC, although Voices is to me the more accomplished and solid book of the series). However, the ending will be much more meaningful if all three were read in sequence. The books are loosly connected by a couple of characters, Orrec and Gry – we meet them as children in Gifts, and finally as adults in the final chapter of Powers. The seperate stories are set in geographically dispersed areas of the Western Shore and concern characters with different magical abilities, or gifts. The gifts are what make the families of the Uplands different, and even feared as witches by Lowlanders.

Le Guin is in familiar territory when telling Gavir’s story. Like the previous books, the narrative is told from the first-person perspective. Gavir is the house slave of a wealthy, cultured and relatively enlightened and benign family in a town called Arcamand. He has two gifts, the ability to see events that have not yet happened, as a "memory," and the ability to remember anything he has read, able to recite the complete story verbatim. One is clearly supernatural, the other, arguably, not. In the end, though, the magical abilities are less important than the social circumstances of the characters. A thread seems to run through the series: a reluctance, perhaps even a fear, to use these gifts. The question is one of power and the consequences of its use and misuse and of choice. Towards the end, when Gavir is tutored by Dorod, this choice becomes brutaly clear: control and use the power and accept the cruelty that it brings, or find another way. Wisely, early in the book, Gavir’s sister convinces him to never reveal his abilities. It is not a spoiler to reveal that Gavir does find another way.

Initially all is well. Gavir is truly happy and content with life, albeit a life badly distorted by the mechanisms of organised slavery. The first section of the book is clearly recounted by a priviliged slave living in far better conditions generally associated with his kind, even to the extent that he may go to school. With subtelty that’s almost cogent, Le Guin unravels the true nature of the oppressive society, showing just how capricious the amity of the household can be, and how utterly dangerous Gavir’s trust in his owners is. As his character develops, Gavir gradually comes to understand and accept even the betrayal of his trust. At this point Le Guin demonstrates yet again the range and depth of her artistry as Gavir informs us:

"It grieves me that blind hate and rancour should be my last link to Arcamand. I could think now of the people of that house with gratitude for what they had given me – kindness, security, learning, love. I could never think that Sotour or Yaven has or would have betrayed my love. I was able to see, in part at least, why the Mother and the Father had betrayed my trust. The master lives in the same trap as the slave, and may find it even harder to see beyond it. But Torm and his slave-double Hoby never wanted to look beyond it; they valued nothing but power, the most brutal control over people. My escape, if he heard of it, would have rankled Torm bitterly. As for Hoby, always seething with envious hatred, the knowledge that I was going about as a free man would goad him to rageful, vengeful persuit" (page 355, Orion edition 2008).

Where Gavir once may have believed that a social order of master and slave is the natural way of things, he slowly begins to percieve the true injustice of it, and when a horrible tragedy strikes, his life begins to rapidly change. Almost by accident Gavir escapes his slavery, and the narrative transforms into a compelling and riveting journey with equally compelling characters. When Gavir takes to the road, heading back to his people, it’s the beginning of his coming of age journey. He must try to understand the nature of his own talents, but always his past as a slave haunts him, like a shadow. Hoby, who once bullied him before he made his escape, ultimately after many years’ searching, tracks him down. The river crossing explained in a few short paragraphs remains for me one of the most touching and unforgettable narratives in all of Le Guin’s work, a symbolic crossing perhaps every child is destined to make.

"The way to go was plain at first, the clear water showing me the shallows between the shoals. Out of the middle of the water, I looked back once. The horseman had seen us. He was just riding into the river, the water splashing up about his horse’s legs. It was Hoby. I saw his face, round, hard, and heavy, Torm’s face, the Father’s, the face of the slave owner and the slave…. I saw it all in a glance and waded on, crosscurrent, pulling the child with me as best I could…. I knew where I was then. I had been in this river with this burden on my shoulders. I did not look around because I do not look around, I go forward, almost out of my depth, but still touching bottom, and there is the place that looks like the right way to go…." (pages 369-370, Orion edition 2008).

Le Guin’s metaphors and imagery and insights are no less powerful, no less beautiful. She can still create myths.

Le Guin’s metaphors and imagery and insights are no less powerful, no less beautiful. She can still create myths.

The final two chapters of Powers are just overwhelmingly moving, simply spectacular, and the reason why this series is now one of my favourites, alongside Earthsea. Gavir becomes a character to really like, endearing and respected, not only because of his love for scholarship and reading, but because of Le Guin’s remarkable and canny ability to remember and depict the crises and concerns of adolescence that could easily have been my story. Attentive readers will meet themselves and, sadly, the worst of the societies we live in.

Powers still resonates with me, long after I finished it. Le Guin’s familiar subjects and motifs are still present, as the all-encompassing political concern for the protection and the nurture of human freedom in all aspects of human life, and the urgent need for the creation of a real human community. This is a message I don’t mind young adults hearing. There is no miraculous conversion of slave owners, renouncing their evil, oppressive ways. Like life, there are no easy answers, but in the end, hanging on, things do get better. I, for one, do believe that.

Highly recommended, not only for young adults.

Full Details

Full Details

2 Comments

Thanks for the review. I just recently learned that this series existed. I’ve ordered copies for my college’s library (We had the first one, but not the other two). We train many teacher here. We try to have YA books that fit many genres so that the teacher candidates can read widely before they enter the classroom.

Kudos to you for exposing the candidate teachers to these books! Even though "Powers" can be read without having read "Gifts" and "Voice" I do suggest they read all three in sequence. Being familiar with the setting of the Western Shore will make the narrative more rewarding, even more touching, and certainly give the ending a far greater impact. In "Powers" particularly, books and education and knowledge are all central to Gavir’s coming of age. It is through a book by one of the protagonists in "Gifts" that Gavir is exposed to the concept of liberty: "It was the first book I’d ever owned. It was the first thing I’d ever owned. I called what I wore my clothes, the desk I used in the schoolroom I called my desk, but in fact they were not mine, they were a property of the house of Arca, as I was. But this book, this was mine."

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.