Forays into Fantasy: The Castle of Otranto, the Gothic Novel and the Origins of Fantasy

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

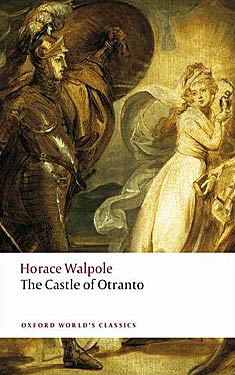

As my interest in science fiction was revived over the last couple of years, and I decided to expand my reading into fantasy as well, I went in search of context. Looking for a guide to some superior and important examples of fantasy, beyond the usual suspects, I pulled David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels off the shelf (and examples of some of these novels will continue to show up in this series of posts), but Pringle begins in 1946, and I wanted to start at the beginning. Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, published in 1988, starts in the eighteenth century. Specifically, the first book listed is Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) — no surprise there. The other three examples from the 1700s, though, I had never heard of before: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, Vathek by William Beckford, and The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis. Upon reading Cawthorn and Moorcock’s essays, it became clear that these were all examples of early Gothic novels, which make up one of the earliest strands of the fantasy genre.

As my interest in science fiction was revived over the last couple of years, and I decided to expand my reading into fantasy as well, I went in search of context. Looking for a guide to some superior and important examples of fantasy, beyond the usual suspects, I pulled David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels off the shelf (and examples of some of these novels will continue to show up in this series of posts), but Pringle begins in 1946, and I wanted to start at the beginning. Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, published in 1988, starts in the eighteenth century. Specifically, the first book listed is Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) — no surprise there. The other three examples from the 1700s, though, I had never heard of before: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, Vathek by William Beckford, and The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis. Upon reading Cawthorn and Moorcock’s essays, it became clear that these were all examples of early Gothic novels, which make up one of the earliest strands of the fantasy genre.

So, did fantasy as a genre really begin in the 1700s (clearly, there was fantastic literature prior to that), and what role did these Gothic novels play in those beginnings? During this eighteenth century, poets and philosophers debated the nature of imagination, and there was a new and rising view that the imagination was not merely a repository of memory and observation, but was a faculty capable of the visionary illumination of the unknown, as Samuel Coleridge and William Blake tried to do in their poetry. In literature, these ideas led to the ongoing distinction between the realistic and the fantastic. As Gary K. Wolfe writes in “Fantasy from Dryden to Dunsany,” in The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature (2012):

“The modern fantasy novel, and to an arguable extent the modern novel itself, is in part an outgrowth of this debate. While we can reasonably argue that the fantastic in the broadest sense had been a dominant characteristic of most world literature for centuries prior to the rise of the novel, we can also begin to discern that the fantasy genre may well have had its origins in these eighteenth- and nineteenth-century discussions of fancy vs. imagination, history vs. romance…”

In particular, Wolfe sees the fantasy genre as arising from three sources during the 1700s and 1800s: “private history” novels such as Robinson Crusoe, a revival of interest in old folk tales and fairy tales, and the vogue for Gothic novels, all three of which required the use of imagination to envision what we now think of as “the fantastic.”

Where, then, did this Gothic strand of literature arise from, and what does it entail? Our story begins during the latter stages of the Roman Empire, when the Goths pillaged their way south from Scandinavia, ultimately sacking Rome in 410. After gaining control of the Italian peninsula, they eventually lost power later in the Middle Ages, after sundry violent run-ins with the Huns, the Franks, and the Moors. Due to its association with the decline of the Classical world, the term “Gothic” came into use during the 1500s as a pejorative term for a medieval style in art and architecture, from the twelfth — through the sixteenth — centuries, which was considered during the Renaissance to be ugly and barbaric when compared to the Classical art and architecture it supplanted. It is best represented by the intricate and sculpturally adorned Medieval cathedrals with their soaring pointed arches, which took advantage of advances in structural design to achieve previously unprecedented height, with correspondingly tall windows and, of course, lots of gargoyles.

Where, then, did this Gothic strand of literature arise from, and what does it entail? Our story begins during the latter stages of the Roman Empire, when the Goths pillaged their way south from Scandinavia, ultimately sacking Rome in 410. After gaining control of the Italian peninsula, they eventually lost power later in the Middle Ages, after sundry violent run-ins with the Huns, the Franks, and the Moors. Due to its association with the decline of the Classical world, the term “Gothic” came into use during the 1500s as a pejorative term for a medieval style in art and architecture, from the twelfth — through the sixteenth — centuries, which was considered during the Renaissance to be ugly and barbaric when compared to the Classical art and architecture it supplanted. It is best represented by the intricate and sculpturally adorned Medieval cathedrals with their soaring pointed arches, which took advantage of advances in structural design to achieve previously unprecedented height, with correspondingly tall windows and, of course, lots of gargoyles.

As pointed out by Adam Roberts in his essay on “Gothic and Horror Fiction” also in The Cambridge Companion, by the time the term “Gothic” was first used to describe a form of literature, in the mid-eighteenth century, its “primary signification… was that of barbarous anti-enlightenment.” At the same time, a revival of interest in Gothic aesthetics would result in the term becoming more complimentary in the eyes of those who began to bring the now old-fashioned medieval styles back into fashion. Among these was Horace Walpole, who rebuilt his London mansion in what he considered to be a “Gothic” style, and wrote what is generally agreed to be the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto: A Story, published in 1764. (Subsequent editions would be subtitled A Gothic Story.)

Walpole originally published The Castle of Otranto under a pseudonym, claiming in the preface that it was a translation of a recently discovered manuscript printed in 1529 and most likely written between 1095 and 1243, thus pretending to establish it as an actual work of the Middle Ages. He speculates that it was written by a priest in order to “avail himself of his abilities as an author to confirm the populace in their ancient errors and superstitions” at a time when such superstitions were being challenged by the Italian intelligentsia. Although presented by the translator as a mere entertainment:

“Some apology for it is necessary. Miracles, visions, necromancy, dreams, and other preternatural events, are exploded now even from romances. That was not the case when our author wrote; much less when the story itself is supposed to have happened. Belief in every kind of prodigy was so established in those dark ages, that an author would not be faithful to the manners of the times, who should omit all mention of them. He is not bound to believe them himself, but he must represent his actors as believing them. If this air of the miraculous is excused, the reader will find nothing else unworthy of his perusal. Allow the possibility of the facts, and all the actors comport themselves as persons would do in their situation… Terror, the author’s principal engine, prevents the story from ever languishing; and it is so often contrasted by pity, that the mind is kept up in a constant vicissitude of interesting passions.”

Clearly, Walpole was aware of the debate over the role of imagination in literature described above by Wolfe, and was attempting to combine the virtues of the modern novel with the fanciful content of ancient stories and myths. Ironically, while claiming to apologize to the reader for the old-fashioned fantastical elements in the story, what Walpole was really doing, by bringing these elements into a novel, was to create something entirely new. In the Middle Ages, people really were superstitious, and such stories would not have been considered “fantastic” in the modern sense. By the 1700s, by which time the Enlightenment had banished superstition from the educated mind, bringing back the fantastic required a new use of imagination for both writers and their audience.

Clearly, people were ready for it. In a popular and commercial sense, his experiment was very successful, unleashing a sea of imitators. Despite Walpole’s apology for it, it is that very “air of the miraculous” that makes the novel intriguing. The plot itself is quite ludicrous, but individual incidents, and the overall mood, keep things interesting. Manfred, lord of the Castle of Otranto, while overseeing the wedding of his sickly son Conrad to Isabella, is shocked and dismayed when a giant helmet appears and crushes Conrad to death, leaving Manfred without an heir. The enormous helmet is otherwise identical to that once worn by Alfonso the Good, who is supposed to have granted the castle to Manfred’s grandfather many years before. Clearly concerned about the implications of this strange event, and determined to maintain his family’s succession, he announces his intention to divorce his wife Hippolita, who has been incapable of providing him with another son, and marry Isabella himself. Neither woman is pleased. Isabella escapes with the help of Theodore, whom Manfred sentences to death. Chasing Theodore and Isabella into the vaults beneath the castle, Manfred encounters an apparition of his grandfather, as well as manifestations of giant armored body parts and weapons, presumably arising from the same source as the helmet. As Manfred had feared, these visions herald the fulfillment of a prophecy that foretold the end of his family’s usurpation of the castle, and the return of its rightful heir, who turns out to be Theodore. Isabella ends up Queen of the castle after all.

Clearly, people were ready for it. In a popular and commercial sense, his experiment was very successful, unleashing a sea of imitators. Despite Walpole’s apology for it, it is that very “air of the miraculous” that makes the novel intriguing. The plot itself is quite ludicrous, but individual incidents, and the overall mood, keep things interesting. Manfred, lord of the Castle of Otranto, while overseeing the wedding of his sickly son Conrad to Isabella, is shocked and dismayed when a giant helmet appears and crushes Conrad to death, leaving Manfred without an heir. The enormous helmet is otherwise identical to that once worn by Alfonso the Good, who is supposed to have granted the castle to Manfred’s grandfather many years before. Clearly concerned about the implications of this strange event, and determined to maintain his family’s succession, he announces his intention to divorce his wife Hippolita, who has been incapable of providing him with another son, and marry Isabella himself. Neither woman is pleased. Isabella escapes with the help of Theodore, whom Manfred sentences to death. Chasing Theodore and Isabella into the vaults beneath the castle, Manfred encounters an apparition of his grandfather, as well as manifestations of giant armored body parts and weapons, presumably arising from the same source as the helmet. As Manfred had feared, these visions herald the fulfillment of a prophecy that foretold the end of his family’s usurpation of the castle, and the return of its rightful heir, who turns out to be Theodore. Isabella ends up Queen of the castle after all.

The genre ushered in by Walpole’s story remained very popular until about 1820, and continued to evolve thereafter (think of Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights, Dracula, and Rebecca). Very few of the novels from the original flowering of the Gothic are still read, but they represented an unleashing of imaginative literature that would ultimately lead to the development of the modern genres of horror (which still maintains an explicitly gothic strand), fantasy, and even science fiction, whose readers are often looking for the same “sense of wonder” as was the original audience for gothic fiction.

The characteristic feeling evoked by the Gothic story is the combination of the familiar and the foreign — the simultaneous attraction and repulsion that Freud wrote about as “the uncanny.” This characteristic of the Gothic has to do with the mood rather than the well-known trappings of the stories — the feeling of mysteriousness, that there are things happening that we can’t quite understand and that may ultimately remain obscure; that important realizations are just out of reach in the shadows and gloom. The reader wants to find out what horrors (usually evils from the past returning to haunt the present) underlie the events in the story, but at the same time is afraid to find out.

The typical elements of the settings in which these strange stories play out have become iconic. As Adam Roberts explains:

“In Otranto we find, in nascent form, many of the props and conventions that were to reappear in the scores of novels published at the height of the Gothic vogue…: moody atmospherics, picturesque and sublime scenery, darkness, buried crimes (especially murderous and incestuous crimes) revealed, and most of all a spectral supernatural focus. Many imitators tried to follow Walpole’s commercial success by littering their novels with similar props, settings and conventions — the haunted castle, the night-time graveyard, the Byronic villain and so on,”

But the elements that make the works successful are not these outward trappings, but rather their ability to invoke the uncanny and the transgressive, and to fire the reader’s imagination.

But the elements that make the works successful are not these outward trappings, but rather their ability to invoke the uncanny and the transgressive, and to fire the reader’s imagination.

As for Otranto in particular, it is the first, but not the very best. Fantasy readers today will have no problem with the fantastic elements, but may struggle with the improbable plot twists, many of which hinge on mistaken or hidden identity, and with the overwrought dialogue. Those willing to make allowances, however, will be carried along by the onrushing events and the feverish intensity of the characters’ emotions and actions, until the situation they are caught up in is finally resolved. These events, manifested through supernatural interventions into the real world, were precipitated by past injustice, a pattern which will play out again in subsequent Gothic novels, often within some variation on Walpole’s shadowy castle and subterranean vaults, literary images that have never ceased to haunt readers of the fantastic.

Next: More early Gothic novels will be reviewed in a future post, but up next is a 1949 American fantasy novel set in a land where stories are real: Silverlock by John Myers Myers.

The Horror! The Horror! – In Which I Confront Fear

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. This is the start of a new series where Dee explores the darker side of genre fiction and it’s practitioners. Be sure to visit his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com for more genre goodness.

Depending upon which survey you read, somewhere between 30% and 50% of Americans believe in ghosts.

Depending upon which survey you read, somewhere between 30% and 50% of Americans believe in ghosts.

That number seems high to me, and I would like to know how each survey phrased the question. If some one hated to be rude to the lingering dead and deny their existence entirely, did they waffle and say, "Well, maybe," and then get classified with the yea sayers? Were they merely ghost agnostics, wanting to leave at least a tiny rent in the veil that separates the living from the dead? After all, how can you really know?

I realize that I am about to lose potentially between a third and one half of my already scant readership here, but I have to say that on this one point at least, people who believe in ghosts simply are not very bright. Now all those same people are saying that I’m not very open-minded to shut the door on the very possibility of a spirit lingering after the body’s death, but you know, fuck that. Grow up.  Ghosts answer a variety of needs in peoples’ lives, from comfort to punishment, but they are not real. There are many creepy aspects to deserted houses, lonely country roads, bad parts of town, and abandoned mental hospitals, but they have nothing to do with ghosts. The night you saw your grandmother, a week after her death, sitting at the foot of your bead may have seemed very real — I know it did in my case — but she was not a ghost.

Ghosts answer a variety of needs in peoples’ lives, from comfort to punishment, but they are not real. There are many creepy aspects to deserted houses, lonely country roads, bad parts of town, and abandoned mental hospitals, but they have nothing to do with ghosts. The night you saw your grandmother, a week after her death, sitting at the foot of your bead may have seemed very real — I know it did in my case — but she was not a ghost.

Having said all this, I admit that the only thing that really scares me, in movies or stories, is a ghost or a haunted house. Vampires, werewolves, serial killers, monsters large and small are there for my entertainment. If one leaps out from behind a closed door I may jump out of my seat with the rest of the audience, but I would do the same thing if a CPA jumped out from behind a closed door. That is nothing more than being startled. But ghosts are uncanny. They worm their way into that part of my brain that knows better but cannot fight back the reflex reaction that raises goosebumps or makes you wish the wife would just stay in her room and not check out those noises downstairs.

I blame my parents. When I was in seventh grade they gave me the Modern Library, Giant Edition, Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural. The stories terrified and delighted me. They were almost all of either Victorian or Edwardian vintage, and that specific diction in a story, the sound of the Oxford Don hesitant to tell his tale for fear of being thought mad, still does it for me. Films and modern writers that attempt that exact atmosphere tend to be creaky and ineffectual. But there are endless modern variations. I find modern vampire stories silly and serial killers tedious if sometimes disgusting, but a film like Paranormal Activity can have me squirming in my seat. (At least the first one did. I just saw Paranormal Activity 3 and felt like I was hearing the same joke for the third time. Although it had its moments.)

I blame my parents. When I was in seventh grade they gave me the Modern Library, Giant Edition, Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural. The stories terrified and delighted me. They were almost all of either Victorian or Edwardian vintage, and that specific diction in a story, the sound of the Oxford Don hesitant to tell his tale for fear of being thought mad, still does it for me. Films and modern writers that attempt that exact atmosphere tend to be creaky and ineffectual. But there are endless modern variations. I find modern vampire stories silly and serial killers tedious if sometimes disgusting, but a film like Paranormal Activity can have me squirming in my seat. (At least the first one did. I just saw Paranormal Activity 3 and felt like I was hearing the same joke for the third time. Although it had its moments.)

Recently I have begun reading horror novels. The Horror Writers Association has published a list of 40 must reads in the genre, many of which I must have read in Junior High and High School. I have also taken a look at the annual Bram Stoker Award winners. It’s an interesting list with some surprises. Joyce Carol Oates, no doubt, was delighted to win in 1996 for a book I’ve never heard of called Zombie, but how must a writer the quality of Stewart O’Nan have felt about first being nominated and then losing out to a novel by Peter Straub in 2003?

Recently I have begun reading horror novels. The Horror Writers Association has published a list of 40 must reads in the genre, many of which I must have read in Junior High and High School. I have also taken a look at the annual Bram Stoker Award winners. It’s an interesting list with some surprises. Joyce Carol Oates, no doubt, was delighted to win in 1996 for a book I’ve never heard of called Zombie, but how must a writer the quality of Stewart O’Nan have felt about first being nominated and then losing out to a novel by Peter Straub in 2003?

I have misgivings about the length of most of these books. How can anything be scary for 400 pages? But I am approaching this with an open mind, hoping for entertainment and the occasional creepy moment. And yes, they will find their way here and onto Potato Weather. I hope to use the word putrescent a great deal.

Novelettes, Unveiled!

Our recent post on where to read the Hugo nominated short stories for free has been by far our most popular post ever (500 clicks from our Twitter feed, and counting). We should have seen that coming. After all, who doesn’t want free award-nominated SF/F? Since it was such a hit, we thought we’d do a follow up on all of the novelettes that were recently nominated for the 2012 Hugos.

Before I show you the list, I should (once more) remind you that a Chicon 7 (Worldcon 70) membership will garner you digital copies of all five novels, six novellas, five novelettes, and five short stories. We highly recommend you attend the con, of course (because then you can visit our booth!), but even if you lack the spare time (and spare change) for that, you can get a supporting membership for only $50… far less than the cost of buying all those stories and books. Plus, you get to vote, which gives you the right to complain about who actually won, Christopher Priest style.

Still, it’s possible that you don’t care to vote, or can’t afford the cash, or (as is the case with me) can’t wait for the Chicon committee to release the reader packets in May. Well, your wait is over. I looked far and wide to find the nominated novelettes, and while they are not all free, most of them are. They are as follows:

- The Copenhagen Interpretation by Paul Cornell (free!)

- Fields of Gold by Rachel Swirsky (free!)

- Ray of Light by Brad Torgersen

This one is interesting, and I expect this to be a phenomenon that will grow in the coming years. You may read the bulk of the story here, but the entire story is for sale on Kindle or Nook at a buck and a half. Not bad.

- Six Months, Three Days by Charlie Jane Anders (free!)

- What We Found by Geoff Ryman

This is a little more complicated. I haven’t found it anywhere online by itself, but it is part of a collection called The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year (Volume 6). The price, $13.59, isn’t bad for a whole collection, but may be a bit hefty if all you want to do is read this one novelette. You could always buy the back issue of its original publication (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March/April 2011) for $9.50, but that seems more of a hassle for not much savings. I, personally, am quite surprised that I can’t buy back issues on Kindle or Nook. Does anyone know if that is possible? Some readers might find this novelette worth the price, as it received a nomination for both the Hugo and Nebula awards.

If there are any updates on these novelettes, I will redact this blog post, and I’ll tweet that I have done so (@wwend). Fair enough? Next up: Novellas!

SF/F Quotes: Arthur C. Clarke

“

Before you become too entranced with gorgeous gadgets and mesmerizing video displays, let me remind you that information is not knowledge, knowledge is not wisdom, and wisdom is not foresight. Each grows out of the other, and we need them all.

”

GMRC Review: Bellwether by Connie Willis

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog. This is Allie’s third GMRC review.

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog. This is Allie’s third GMRC review.

Note: This review was originally posted on Allie’s blog and was submitted last month but got overlooked.

Bellwether by Connie Willis

Bellwether by Connie Willis

Published: Bantam Spectra, 1996

Awards Nominated: Nebula Award, 1997

The Book:

“What makes something become a fad? That’s the question Sandra Foster wants to answer through her research for HiTek Corporation. HiTek’s bureaucratic atmosphere isn’t making her task any easier. Sandra is constantly derailed by overcomplicated paperwork, meetings, HiTek’s obsession with acquiring a prestigious grant and her supremely incompetent fad-following office assistant, Flip.

Thanks to a mis-delivered package, Sandra gets to know her fellow HiTek researcher Bennet O’Reilly, who works with monkey group behavior and chaos theory. Sandra is initially interested in him due to his strange immunity to fads, but their acquaintanceship quickly moves towards a closer collaboration. As their research spirals out of control, Bennet and Sandra search for the link between chaos theory, romance, fads, and a flock of sheep…” ~Allie

I’ve read a lot of Willis’ work, though this is the first book I’ve read outside of her time travel novels (Doomsday Book, Blackout / All Clear, To Say Nothing of the Dog). Bellwether is definitely characteristic of Willis’ style, but it is also a light, silly romantic comedy. This is also the third novel I’ve reviewed for the Grand Master Reading Challenge, hosted by WWEnd.com, a fantastic website I recommend highly for any fans of speculative fiction.

My Thoughts:

Bellwether does feature scientists, but it doesn’t really seem like a science fiction story. I can’t help but wonder if it was simply labeled that way out of habit, since most of Willis’ work is science fiction. Bellwether is mostly a light, satirical romantic comedy about fads, scientific discoveries, and office politics. Willis’ familiar style is present here, as she draws humor out of obnoxious side characters, miscommunication, incompetence, and all the little frustrations that crop up in everyday life. Bellwether is more in the vein of To Say Nothing of the Dog than Doomsday Book or Blackout / All Clear. It is by far the shortest and fluffiest Connie Willis novel I’ve ever read, but it was a very pleasant, light read.

Throughout the story, Willis includes little facts about real fads and circumstances around unexpected scientific breakthroughs. I really enjoyed these inserts, though I think this attention to historical and recent-to-publication (1990s) fads dates the book. It happens to be just the time period to invoke nostalgia for me, but I’m not sure how well this would fly with people who aren’t in my generation. There are a lot of ‘current’ fads introduced in the novel as well. Most of these are believably ridiculous, but some of them seem unlikely to occur in our current times. I think that it is the nature of fads to become obsolete very quickly, and the fad-focused setting causes the book to be very much a product of its time.

Aside from the fads, there was a lot of satire of office culture. Having dealt with bureaucracy extensively, I found this satire ridiculously stressful to read. To ‘help’ their employees’ productivity, HiTek had constant meetings and workshops, and a lot of time was spent describing their required paperwork, which was so ridiculously complicated that it actually obstructed employee progress. Included in this satire is also one of the major ‘obnoxious characters’, the office assistant Flip. Flip is a trendy young woman who doesn’t really do anything useful, and instead seems to damage productivity everywhere she goes. Sandra tries to make the best of things by befriending her, but this only makes her behavior worse. I think many people who’ve worked in an office environment have probably been stuck at some point with someone as lazy and incompetent as Flip.

Aside from the fads, there was a lot of satire of office culture. Having dealt with bureaucracy extensively, I found this satire ridiculously stressful to read. To ‘help’ their employees’ productivity, HiTek had constant meetings and workshops, and a lot of time was spent describing their required paperwork, which was so ridiculously complicated that it actually obstructed employee progress. Included in this satire is also one of the major ‘obnoxious characters’, the office assistant Flip. Flip is a trendy young woman who doesn’t really do anything useful, and instead seems to damage productivity everywhere she goes. Sandra tries to make the best of things by befriending her, but this only makes her behavior worse. I think many people who’ve worked in an office environment have probably been stuck at some point with someone as lazy and incompetent as Flip.

Most of the plot featured Dr. Sandra Foster as she went about her daily life, attempting all the while to find the origin of hair bobbing. This may sound boring, but I think that describing daily life in a light, humorous way is Willis’ forte. Sandra goes through children’s birthday parties, cafes, libraries, and HiTek, observing everything with an eye towards fads and absurdities. The romance in the story is pretty obvious and predictable, but adorable all the same. The conclusion was as chaotic and ridiculous as expected, and the whole story left me in a cheerful mood. Bellwether is certainly a light read, but it was a lot of fun.

My Rating: 3.5/5

Bellwether is a satire of fads and office culture and a romantic comedy, but it didn’t really seem like a science fiction story. The story is much lighter, shorter and more carefree than many of Willis’ other novels, but her style was still here in full force. There’s no time-traveling Oxford (as in Doomsday Book, To Say Nothing of the Dog, etc.), but her characters still come up against irritating minor characters, minor frustrations, and ridiculous bureaucracy. The focus on fads, and some of the attitudes of the main characters, left the story feeling firmly set in the 90s, and it will likely feel even more dated to readers who haven’t lived through that decade. The writing was light and humorous, the characters were likeable or likeably obnoxious, and the predictable eventual romance was very cute. It may lack the depth and gravity of some of her other works, but Bellwether is a funny, cheerful book that made for pleasant light reading.

2011 British Science Fiction Association Award Winners Announced

The winners of the 2011 British Science Fiction Association Award were announced last night at Eastercon. The winners are:

The winners of the 2011 British Science Fiction Association Award were announced last night at Eastercon. The winners are:

- Novel: The Islanders – Christopher Priest (Gollancz)

- Short Fiction: "The Copenhagen Interpretation" (PDF) – Paul Cornell (Asimov’s, July)

- Artwork: Cover of Ian Whates’s The Noise Revealed – Dominic Harman (Solaris)

- Non-Fiction: The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, 3rd Edition ed. – John Clute, Peter Nicholls, David Langford and Graham Sleight

Visit the BSFA website for the complete list of nominees in all categories. Congratulations to the winners and nominees.

It’s certainly been a busy weekend for awards – PKD winners, Hugo Nominees and now the BSFA winners! What do you think of Christopher Priest’s The Islanders for best novel?

Thanks to SF Signal for the report.

Short Stories, Unleashed!

It’s true that Worlds Without End mainly covers award winning SF/F/H novels, but, as we all know, novelists write in all kinds of formats. With the recent announcement of the 2012 Hugo Award nominees, we though you might be interested in reading all of the stories that were nominated, including novellas, novelettes and short stories. Our crack team of researchers (okay, just me) has been feverishly working to find where you can find all of the stories that Worldcon members have chosen to put before us fans. Here is what I found.

It’s true that Worlds Without End mainly covers award winning SF/F/H novels, but, as we all know, novelists write in all kinds of formats. With the recent announcement of the 2012 Hugo Award nominees, we though you might be interested in reading all of the stories that were nominated, including novellas, novelettes and short stories. Our crack team of researchers (okay, just me) has been feverishly working to find where you can find all of the stories that Worldcon members have chosen to put before us fans. Here is what I found.

First, I highly recommend Chicon7 (hence Worldcon 2012) membership. If you can’t afford an attending membership of $215 (as of this writing, installment plan available) or can’t make it out to Chicago, the supporting membership is only $50, and it includes digital copies of all five novels, six novellas, five novelettes, and five short stories for your perusing. The novels alone would cost more than $50 to buy. Chicon7 has told us that the reading packets will be out by May.

Of course, we know that you don’t want to wait until May to read some of these outstanding stories, so here are some more fruits of our research labors. All five nominated short stories can be read for free online right now (except one…but it’s coming it’s here). I also included the original publication dates, in case you just want to go out and buy a back issue:

- Shadow War of the Night Dragons: Book One: The Dead City: Prologue has long been online, since it was published by John Scalzi as an April Fools joke that has clearly gone rogue.

- The Paper Menagerie by Ken Liu was originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Fiction (March/April 2011). That link is actually to a PDF format, so this story may be transferred to your e-reader of choice. Also, there is a short interview with Ken Liu here.

- Movement by Nancy Fulda was published Asimov’s (March 2011), but you audio book readers can catch a podcast version here.

- The Homecoming by Mike Resnick has not yet been published online, but Mr. Resnick has said that Asimov’s will be making it available soon. is also in PDF format (now). Find it in dead tree format by obtaining the April/May 2011 edition of Asimov’s. We will update this post updated this post when a digital copy becomes became available.

- The Cartographer Wasps and the Anarchist Bees by Lily Yu was published by Clarkesworld (April 2011).

We hope that this keeps you satisfied for a little while, while we wait for our Worldcon readers packets. I know my personal goal is to read every nominated story, so that I can actually fill out a whole Hugo ballot.

Next up: Novelettes!

2012 Hugo Award Nominees Announced

The 5-convention simulcast is over, and the 2012 Hugo Award nominees have been announced. The nominees for Best Novel are:

- Among Others by Jo Walton (Tor)

- A Dance With Dragons by George R. R. Martin (Bantam Spectra)

- Deadline by Mira Grant (Seanan McGuire) (Orbit)

- Embassytown by China Miéville (Macmillan / Del Rey)

- Leviathan Wakes by James S. A. Corey (Ty Franck and Daniel Abraham) (Orbit)

See the the complete list of nominees in all categories on the home page of the Chicon 7 website. Congratulations to all the nominees.

What do you think of this year’s lineup? Anything you really like on this list? Anything make you scratch your head in confusion? More importantly, will it satisfy Christopher Priest?

2011 Philip K. Dick Award Winner

The winner of the 2011 Philip K. Dick Award has been announced.

The winner is: Samuil Petrovitch Trilogy – Simon Morden (Orbit)

Special Citation was given to: The Company Man – Robert Jackson Bennett (Orbit)

The announcement was made last night at Norwescon 35 in SeaTac WA. This marks the first time that the PKD Award has gone to a trilogy. Congratulations to Simon Morden and Robert Jackson Bennett and all the nominees. What a banner day for Orbit!

What do you think of the result?

2012 Hugo Award Nominees to be Announced Tomorrow – Live

![]() The 2012 Hugo Award nominees will be announced tomorrow on a live stream that starts at 3 p.m. CT. In an impressive display of technological competence, they will stream simultaneously at five conventions in the US and Europe. We will, of course, post the results here on the blog, in BookTrackr, and on our Twitter feed as soon as the results are announced.

The 2012 Hugo Award nominees will be announced tomorrow on a live stream that starts at 3 p.m. CT. In an impressive display of technological competence, they will stream simultaneously at five conventions in the US and Europe. We will, of course, post the results here on the blog, in BookTrackr, and on our Twitter feed as soon as the results are announced.

In case you’d like to know even (seconds) earlier, here are the five streams where you can catch the nominating action live (lifted from chicon.org):

- Norwescon 35: one of the Pacific Northwest’s premier science fiction and fantasy conventions, at Seatac, WA (1 p.m. PDT). With Special Guest John Picacio. Ustream channel www.ustream.tv/channel/hugo-nominee-announcement-live-from-norwescon.

- Leprecon 38: Arizona’s annual science fiction and fantasy convention, at Tempe, AZ (1 p.m. MST). With Special Guest Joe Haldeman. Ustream channel www.ustream.tv/channel/hugo-nominee-announcement-live-from-leprecon.

- Minicon 47: Minnesota’s longest-running science fiction convention, at Bloomington, MN (3 p.m. CDT). Ustream channel www.ustream.tv/channel/hugo-nominee-announcement-live-from-minicon.

- Marcon 47: the Midwest’s largest annual convention, at Columbus, OH (4 p.m. EDT). Ustream channel www.ustream.tv/channel/hugo-nominee-announcement-live-from-marcon.

- Olympus 2012: the British National Science Fiction Convention (Eastercon) (9 p.m. BST). With Chicon 7 Chair Dave McCarty and Special Guest George R.R. Martin. Ustream channel www.ustream.tv/channel/hugo-nominee-announcement-live-from-eastercon.

Full Details

Full Details