Forays into Fantasy: The Mabinogion Tetralogy by Evangeline Walton

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

The paperback republication of The Lord of the Rings in the 1960s and its subsequent wild success created a whole new audience for fantasy, and led to a fantasy publishing boom in the 1970s. Along with spawning, for better or worse, an unending stream of new epic fantasy, the belated popularity of J. R. R. Tolkien also sent publishers looking for other older fantasy novels to reprint. One result was Ballantine’s Adult Fantasy series, which reprinted sixty-five novels between 1969 and 1974, under the editorship of Lin Carter. Books by Lord Dunsany, Clark Ashton Smith, H. P. Lovecraft, William Hope Hodgson, James Branch Cabell, and many others now considered fantasy classics were brought back into print and released as affordable paperbacks for fantasy-hungry readers. One of Carter’s more obscure finds was the eighteenth book in the series, The Island of the Mighty by Evangeline Walton, a novelistic retelling of the fourth “branch” of the Mabinogion—a series of Welsh-language legends of the British Isles dating from the fourteenth century, the stories themselves most likely originating in the twelfth. Though it had received some critical acclaim on release in 1936 under its original unfortunate (though not inaccurate) title The Virgin and the Swine, it had failed to sell and was pretty well forgotten by the time Carter brought it to Ballantine’s attention.

The paperback republication of The Lord of the Rings in the 1960s and its subsequent wild success created a whole new audience for fantasy, and led to a fantasy publishing boom in the 1970s. Along with spawning, for better or worse, an unending stream of new epic fantasy, the belated popularity of J. R. R. Tolkien also sent publishers looking for other older fantasy novels to reprint. One result was Ballantine’s Adult Fantasy series, which reprinted sixty-five novels between 1969 and 1974, under the editorship of Lin Carter. Books by Lord Dunsany, Clark Ashton Smith, H. P. Lovecraft, William Hope Hodgson, James Branch Cabell, and many others now considered fantasy classics were brought back into print and released as affordable paperbacks for fantasy-hungry readers. One of Carter’s more obscure finds was the eighteenth book in the series, The Island of the Mighty by Evangeline Walton, a novelistic retelling of the fourth “branch” of the Mabinogion—a series of Welsh-language legends of the British Isles dating from the fourteenth century, the stories themselves most likely originating in the twelfth. Though it had received some critical acclaim on release in 1936 under its original unfortunate (though not inaccurate) title The Virgin and the Swine, it had failed to sell and was pretty well forgotten by the time Carter brought it to Ballantine’s attention.

As explained in publisher Betty Ballantine’s introduction to Overlook’s 2002 omnibus edition of The Mabinogion Tetralogy (also published under the Fantasy Masterworks banner, of which The Island of the Mighty is the fourth and final book, Ballantine’s desire to publish the novel set in motion a heartwarming series of events. Having initially been informed that the book’s copyright had expired, and having searched fruitlessly for Walton, Ballantine prepared the work for publication, finding out at the last minute that the copyright had in fact been renewed, and that Walton was alive and well and living in Phoenix. Walton’s childhood had been marked by illness that kept her in her home, and medical treatments that resulted in a skin condition that would make her reluctant to appear in public later in life. Seeking refuge in books, she developed a love of fantasy and medieval literature, leading to a determination to retell The Mabinogion as a series of fantasy novels.

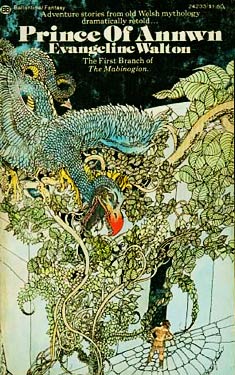

Aged 63 in 1970, Walton was amazed to learn that there was interest in her book, and revealed that she had continued adapting the stories into novels even though she did not believe they would ever be published. Following The Island of the Mighty’s publication in 1970, Ballantine was able to release the now completed manuscripts of the first three branches of the Mabinogion sequence between 1971 and 1974: The Prince of Annwyn, The Children of Llyr, and The Song of Rhiannon. So, while mostly released post-Tolkien, these works really belong to the pre-Tolkien period. The novels received much critical acclaim, and all three were nominated for Mythopoeic Awards (The Song of Rhiannon won one in 1973), and Walton received a World Fantasy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1989. Overcoming her reluctance to appear in public, she took up travel and enjoyed appearing as a guest at science fiction and fantasy conventions. It must have been very gratifying for an author, late in life, to realize such acclaim for works that she had believed to be forgotten.

Aged 63 in 1970, Walton was amazed to learn that there was interest in her book, and revealed that she had continued adapting the stories into novels even though she did not believe they would ever be published. Following The Island of the Mighty’s publication in 1970, Ballantine was able to release the now completed manuscripts of the first three branches of the Mabinogion sequence between 1971 and 1974: The Prince of Annwyn, The Children of Llyr, and The Song of Rhiannon. So, while mostly released post-Tolkien, these works really belong to the pre-Tolkien period. The novels received much critical acclaim, and all three were nominated for Mythopoeic Awards (The Song of Rhiannon won one in 1973), and Walton received a World Fantasy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1989. Overcoming her reluctance to appear in public, she took up travel and enjoyed appearing as a guest at science fiction and fantasy conventions. It must have been very gratifying for an author, late in life, to realize such acclaim for works that she had believed to be forgotten.

The Mabinogion, like the Arthurian legends, the Greek myths, or the ancient manuscripts telling the stories of Gilgamesh or Beowulf, are what critic John Clute calls “taproot texts”—works which, though fantastic by modern standards and important inspirations for fantasy writers, were not written as fantasy, being more or less accepted as representations of real events by their original audiences. In Walton’s version, the stories are retold by an omniscient narrator with access to the Mabinogion manuscripts, who admits to taking liberties with the original source, though without letting the reader completely forget that source. The occasional footnote, philosophical reflection on the events unfolding, or authorial interjection (“The Mabinogi tells that…”) reminds us that we are reading a retelling of these ancient stories, but they do not distract from or impede the flow of the narrative.

The result is a series of novels that in some ways are even more fantastic than most modern fantasies, full of wonderfully described fantastic elements—a woman created magically out of flowers, trips to the underworld and the world of Faery, animal transformations, animated severed heads, all in a world where magic is part of the fabric of life for the characters—with an added sense of strangeness that comes from reflecting on the fact that the people inhabiting the British Isles nearly a millennium ago, who told and listened to these tales, had a mindset quite alien to our own, as evidenced by the attitudes and actions of the characters portrayed, and their acceptance of supernatural events. Of course, these characters, like those of the other taproot texts, are generally archetypes representing various aspects of human nature rather than real people, but Walton adds the humanity that turns them into engaging characters, thus helping to draw us into their stories.

The result is a series of novels that in some ways are even more fantastic than most modern fantasies, full of wonderfully described fantastic elements—a woman created magically out of flowers, trips to the underworld and the world of Faery, animal transformations, animated severed heads, all in a world where magic is part of the fabric of life for the characters—with an added sense of strangeness that comes from reflecting on the fact that the people inhabiting the British Isles nearly a millennium ago, who told and listened to these tales, had a mindset quite alien to our own, as evidenced by the attitudes and actions of the characters portrayed, and their acceptance of supernatural events. Of course, these characters, like those of the other taproot texts, are generally archetypes representing various aspects of human nature rather than real people, but Walton adds the humanity that turns them into engaging characters, thus helping to draw us into their stories.

Walton unifies the loosely collected stories of the Mabinogion by focusing on themes of change hinted at in the original manuscripts. She characterizes the time in which they take place as a period in which the implicitly Christian New Tribes, characterized by a patriarchal culture that promotes monogamous marriage and patrilineal inheritance, has fairly recently invaded the islands previously inhabited by the Old Tribes, who still hold onto a pagan Druidic religion, allow sexual freedom for men and women, reject marriage, and do not recognize the father’s role in conception, maintaining the custom of matrilineal inheritance. The Old Tribes worship “the Mothers” rather than “the Father.” As the ideas of the New Tribes spread among the Old, the kings of the Old Tribes begin to see the appeal of these new ideas, and both The Children of Llyr and The Island of the Mighty center around tragic events set in motion by kings who, though otherwise considered good and wise, attempt to maneuver events in such a way as to install their own sons (instead of their sisters’ sons, as the ways of the Old Tribes prescribe) as their heirs.

In The Children of Llyr, the beloved King Bran of the Island of the Mighty (Britain) sends his sister Branwen, who should be the mother of the next king, to marry the King of Ireland. The Irish King Matholuch sees an opportunity to unite his kingdom and the more powerful Island of the Mighty. Bran agrees with this logic, at first concealing even to himself that sending his sister away might provide him an opportunity to eventually install his own son as king. Bran’s brother Evnissyen, furious at not being consulted, insults the Irish by torturing and killing their horses, in revenge for which Branwen is abused and debased. The resulting war between the two islands results in the deaths of nearly everyone involved, including Branwen’s young son, who should have been the next king of the Islands. King Matholuch, whose forces are no match for Bran’s, resorts to using the magical Cauldron of the Gods, which brings his dead warriors back to life. But this desperate action has consequences, as the uncontrollable undead army leads to an early version of a zombie apocalypse in Ireland.

In The Children of Llyr, the beloved King Bran of the Island of the Mighty (Britain) sends his sister Branwen, who should be the mother of the next king, to marry the King of Ireland. The Irish King Matholuch sees an opportunity to unite his kingdom and the more powerful Island of the Mighty. Bran agrees with this logic, at first concealing even to himself that sending his sister away might provide him an opportunity to eventually install his own son as king. Bran’s brother Evnissyen, furious at not being consulted, insults the Irish by torturing and killing their horses, in revenge for which Branwen is abused and debased. The resulting war between the two islands results in the deaths of nearly everyone involved, including Branwen’s young son, who should have been the next king of the Islands. King Matholuch, whose forces are no match for Bran’s, resorts to using the magical Cauldron of the Gods, which brings his dead warriors back to life. But this desperate action has consequences, as the uncontrollable undead army leads to an early version of a zombie apocalypse in Ireland.

In The Island of the Mighty, Gwydion, heir to the ancient King Mâth, also attempts to install his own son on the throne. Since his sister Arianrhod should be mother to the next heir, Gwydion uses magical means to impregnate her against her will, so that she will give birth to his son. They had a previous incestuous relationship, so Gwydion didn’t think she’d mind this intrusion, but Arianrhod is also infected by the ideas of the New Tribes, who put great stock in the concept of female virginity. Arianrhod, who is by no means a virgin, nevertheless wants to follow the new fashion by being thought of as one, so is understandably upset when Gwydion forces her to give birth. Her three curses on the child result in a battle of wits between the siblings that makes up much of the novel, but again set in motion a series of tragic events for the family.

This conflict between old ways and new is not presented as a good vs. bad dichotomy, however. The inroads of the New Tribes are known as “the Great Going-Forward,” and identified with a sort of progress. (And the New Tribes are not wrong, after all, about the role of the father in reproduction.) But Walton makes it clear that much is being lost as well, and her retelling of the Mabinogion can certainly be read as a feminist work. The shift toward patriarchy decreases the power of women, which is why the male kings and druid priests of the Old Tribes begin to embrace the change, despite the clear break from past traditions. Even Rhiannon, princess of the Bright World of Faery, the highest heaven untainted by violence or any of humanity’s negative impulses, sacrifices that beauty, and her own immortality, in order to be with Pwyll, the human Lord of Dyvd, in Prince of Anwynn. Rebelling against her father, and well aware of what is being lost, she has reluctantly accepted that change must come:

This conflict between old ways and new is not presented as a good vs. bad dichotomy, however. The inroads of the New Tribes are known as “the Great Going-Forward,” and identified with a sort of progress. (And the New Tribes are not wrong, after all, about the role of the father in reproduction.) But Walton makes it clear that much is being lost as well, and her retelling of the Mabinogion can certainly be read as a feminist work. The shift toward patriarchy decreases the power of women, which is why the male kings and druid priests of the Old Tribes begin to embrace the change, despite the clear break from past traditions. Even Rhiannon, princess of the Bright World of Faery, the highest heaven untainted by violence or any of humanity’s negative impulses, sacrifices that beauty, and her own immortality, in order to be with Pwyll, the human Lord of Dyvd, in Prince of Anwynn. Rebelling against her father, and well aware of what is being lost, she has reluctantly accepted that change must come:

“You men and your Gods! You mock at the Mother for snail slowness, for creating blindly in the dark. Yet when you create without Her, swiftly and in the light, you will create blindly indeed—shaping, maybe, a world’s death! Well, poison sea and sky, the air you breathe, and even the sweet brown skin of Her breast, that always She has allowed you to tear to give you grain. Kill and kill until nothing is left but bare bones upon barren, polluted earth. The Mother is mighty; She has many bodies, and your world is but one of them. In Her mightiness She may yet heal Her wounds and make earth bloom again—yes, raise you men along with it, even if She has to bear your whole race again. For a good mother is patient; she knows that a child must stumble many times before it learns to walk… Also you do have your good points. Who should know that better than I?” She laughed, and cradled Pwyll’s head upon her breasts.

Walton herself makes this clear in an afterword to Prince of Annwyn, the first book of the sequence but the last to be published: She credits anthropologist Robert Briffault with giving her “several intriguing ideas to play with. He believed, as I understand him, that civilization first evolved from the efforts of childbearing women to provide for their families, and that when men took over they invented nothing really new until our own machine age appeared, an almost exclusively masculine creation. Pollution has dimmed that last glory a little; I hope I will not be accused of sex bias for saying so; I like penicillin, electric toasters, jet travel, etc., as well as anybody. But when we were superstitious enough to hold the earth sacred and worship her, we did nothing to endanger our future upon her, as we do now. That seems a little ironic.”

Walton herself makes this clear in an afterword to Prince of Annwyn, the first book of the sequence but the last to be published: She credits anthropologist Robert Briffault with giving her “several intriguing ideas to play with. He believed, as I understand him, that civilization first evolved from the efforts of childbearing women to provide for their families, and that when men took over they invented nothing really new until our own machine age appeared, an almost exclusively masculine creation. Pollution has dimmed that last glory a little; I hope I will not be accused of sex bias for saying so; I like penicillin, electric toasters, jet travel, etc., as well as anybody. But when we were superstitious enough to hold the earth sacred and worship her, we did nothing to endanger our future upon her, as we do now. That seems a little ironic.”

Award-winning, derived from an important “taproot text,” beautifully written and with a fascinating feminist subtext that provides much food for thought, it’s surprising that Walton’s tetralogy isn’t better known. I was disappointed to find that it wasn’t included in the recent “Fantasy Mistressworks Fifty” list of the top fantasy novels by women writers. If Walton’s accomplishment is fading from the memory of fantasy fans, these books are ripe for rediscovery.

Next: The origins of sword and sorcery: Robert E. Howard’s Conan.

Full Details

Full Details

4 Comments

This is what fantasy was all about back then…adapting ancient myths to modern storytelling. With so much original fantasy on the bookshelves, these days, I wonder how many long forgotten myths still need rescuing by contemporary authors.

@icowrich: Good question, and authors are beginning to make inroads into areas we haven’t seen before in English-language fantasy. For example, Saladin Ahmed using Arab mythology in Throne of the Crescent Moon, or Nnedi Okorafor’s books incorporating West African legends…

I read the first of these books long ago and really enjoyed it. I don’t know why I didn’t go on to the others. It made me want to seek out the original myths, too, and see how much was already there and how much Walton added.

Thanks for this one, Scott. I really like fantasy that’s build on existing myths. I’m particularly interested in how Walton applies the narrator’s voice. Probably because of my love for Gene Wolfe’s works. Will be looking to get the Overlook omnibus.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.