Forays into Fantasy: Gertrude Barrows Bennett’s The Citadel of Fear

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

In the midst of the Women of Genre Fiction Challenge, I’d like to direct your attention to Gertrude Barrows Bennett—possibly the most important female writer of speculative fiction that you’ve probably never heard of. Her sustained run of fantasy fiction published between 1917 and 1923—around a dozen stories, including five novels—have led to a growing acceptance of her importance to the history of the genre, following decades of neglect.

In the midst of the Women of Genre Fiction Challenge, I’d like to direct your attention to Gertrude Barrows Bennett—possibly the most important female writer of speculative fiction that you’ve probably never heard of. Her sustained run of fantasy fiction published between 1917 and 1923—around a dozen stories, including five novels—have led to a growing acceptance of her importance to the history of the genre, following decades of neglect.

Bennett (1884–1948) turned to writing when her journalist/explorer husband died while on an expedition, soon followed by her father, leaving her with a newborn daughter and invalid mother to support. She seems to have stopped writing after her mother’s death. Following her disappearance from public view, and prior to the idea being debunked in 1952, it was quite widely believed that Francis Stevens—the pseudonym under which Bennett’s work was published—was actually a penname of A. Merritt, probably the most popular and influential fantasy writer of the first third of the twentieth century (though much less well-known today). It turns out; however, that the similarities of their writings, which led readers to assume “Stevens” was Merritt, were quite likely the result of Bennett’s own influence on Merritt, who acknowledged his admiration for her works, and the inspiration he received from them. (Mention has also been made of H. P. Lovecraft’s endorsement of her work, but this story seems to have been apocryphal.)

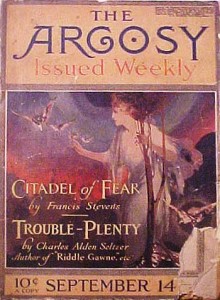

Bennett published almost all her stories in the Munsey pulps Argosy and All-Story. These were fiction pulps that featured stories from multiple genres, including science fiction and fantasy, prior to the debut of the specialized genre pulps in the mid-1920s, and may be best known today for the original serializations of the novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs, which ran contemporaneously to Bennett’s. Her final published story, “Sunfire”, appeared in Weird Tales, the first specialty fantasy pulp, during 1923, its first year of publication. Her active writing career, then, though prolific while it lasted, was quite short, and did not last long enough to establish her among the fans of weird fiction that would coalesce around Weird Tales. In hindsight, however, critics and genre historians have acknowledged Bennett’s importance as one of the founders of the weird tales tradition, and the most important woman writer of fantasy in the early pulp era. In 2004, Gary Hoppenstand, in the title of his introduction to a 2004 collection of Bennett’s short fiction, claims that Bennett/Stevens was “The Woman Who Created Dark Fantasy.”

Though most of her work is still of interest, and her novel The Heads of Cerberus is sometimes noted as the precursor of the entire parallel worlds tradition in fiction, her single best work might be the 1918 novel The Citadel of Fear. In the best pulp tradition, The Citadel of Fear is a triumph of imagination, beginning as a lost world story, but ultimately incorporating into one adventurous novel elements of science fiction, fantasy, horror, and the weird: a mysterious lost city, ancient Aztec gods reborn, a magical idol, and numerous biological monstrosities are just a few of the ingredients of Bennett’s plot. Yet all these ideas are part of a coherent and suspenseful narrative embedded in a novel that includes interesting characters and strong writing, and even a good dose of humor and a bit of romance amidst the prevailing mood of dread—definitely a combination that would have stood out above most of the material appearing alongside it in the pulps, though one that could easily have gone off the rails in the hands of a less talented writer.

Though most of her work is still of interest, and her novel The Heads of Cerberus is sometimes noted as the precursor of the entire parallel worlds tradition in fiction, her single best work might be the 1918 novel The Citadel of Fear. In the best pulp tradition, The Citadel of Fear is a triumph of imagination, beginning as a lost world story, but ultimately incorporating into one adventurous novel elements of science fiction, fantasy, horror, and the weird: a mysterious lost city, ancient Aztec gods reborn, a magical idol, and numerous biological monstrosities are just a few of the ingredients of Bennett’s plot. Yet all these ideas are part of a coherent and suspenseful narrative embedded in a novel that includes interesting characters and strong writing, and even a good dose of humor and a bit of romance amidst the prevailing mood of dread—definitely a combination that would have stood out above most of the material appearing alongside it in the pulps, though one that could easily have gone off the rails in the hands of a less talented writer.

The story begins with explorers Colin O’Hara (“a stalwart young Irishman … who even at twenty excelled most men in strength and stamina”) and Archer Kennedy, near death in the midst of a desert storm while on a gold-finding expedition in South America. Kennedy is gradually revealed as something of a weakling and a scoundrel, in contrast to O’Hara’s uprightness, but O’Hara saves Kennedy’s life, refusing to leave him behind to die. (The character dynamic between these two will be one of the unifying aspects of the story.) They stumble at the last moment onto an oasis, which at first appears to be a plantation, but which is soon revealed as the entrance to a lost Aztec city—Tlapallan. They also encounter another explorer, Svend Biornson, who had previously found the city and taken up residence and befriended its people. As Biornson tells them:

Sometimes I think they are the last remnant of a forgotten race, older than Toltec or Mayan, or even the Olmecs, who have left nothing to archaeology but a memory. And sometimes—I have other thoughts of them, thoughts that I can’t put into words, for there are no words to express them. I know that they speak the Aztec tongue in all its ancient purity, and yet they are surely not of Aztec blood. However it may be, they are good, true comrades, and my own wife is one of them, but I sometimes wonder if I have not—have not lost my soul in living here! I am saying too much—you can’t understand and you must not.

The mystery of Tlapallan (a “mythical city, set in a lake of cold fire, where phantom galleys moved in majestic silence”) involves an ancient rivalry between the gods Quetzalcoatl and Nacoc-Yaotl (the “Lord of Fear”). Nacoc-Yaotl’s priests have the power to create weird and dangerous creatures—werewolves that are allowed to roam the outskirts of the city, helping provide security—but who cannot be allowed to get the upper hand over the forces of Quetzalcoatl, whose followers keep the evil in check. Accidentally witnessing one of the grotesque rituals during which these creatures are created, Kennedy learns the source of Biornson’s warnings:

The mystery of Tlapallan (a “mythical city, set in a lake of cold fire, where phantom galleys moved in majestic silence”) involves an ancient rivalry between the gods Quetzalcoatl and Nacoc-Yaotl (the “Lord of Fear”). Nacoc-Yaotl’s priests have the power to create weird and dangerous creatures—werewolves that are allowed to roam the outskirts of the city, helping provide security—but who cannot be allowed to get the upper hand over the forces of Quetzalcoatl, whose followers keep the evil in check. Accidentally witnessing one of the grotesque rituals during which these creatures are created, Kennedy learns the source of Biornson’s warnings:

Taken by themselves one can tolerate a white dog, a white reed, or a phosphorescent fungus. Assemble them in mire, multiply them, surround them with golden thrones, and roof them with a jewel-lined dome, and the combination becomes—suspiciously weird. Suddenly the man knew that he had seen too much.

The ritual transformations of Nacoc-Yaotl would not be forgotten by Kennedy, and would (along with Kennedy himself),come back to haunt O’Hara late in the novel.

The presence of O’Hara and Kennedy in Tlapallan leads inadvertently to an escalation of the rivalry between Quetzalcoatl and Nacoc-Yaotl, and to the explorers’ escape back to civilization. The mysteries of the city are left unsolved, and the novel, about a third of the way through, in a jarring transition, shifts from exotic Tlapallan to Colin’s sister Cliona’s home in “a small suburb … of a city in the eastern part of the United States,” fifteen years later. At first this abrupt change in setting is disappointing—some of the best sections of the novel are Bennett’s descriptions of the weird city of Tlapallan, with its strange glowing lake and mysterious inhabitants, but it soon becomes clear that the weirdness is invading this new mundane setting. Colin tells Cliona of his recent return visit to Tlappalan, where all he could find were the ruins of Biornson’s hacienda, a small porcelain idol of Quetzalcoatl, and “a lake so deep there was no fathoming it.” Were the events of fifteen years past a delusion? And if not, what of Tlapallan? “Ah, you strange, bright city, do you really lie ruined at the bottom of that black lake—or were you the fancy of a fever?”

Possibly attracted by the idol, which Colin had given to Cliona, strange visitations of her home begin to take place, escalating in violence and destructiveness. Colin discovers that he source of the late-night marauders may be the estate of the mysterious Chester Reed, an exotic animal breeder recently established in the neighborhood, and who seems strangely familiar to O’Hara upon their meeting. Getting to the bottom of the mystery, Colin, Cliona, and her husband are abetted by Detective McClelland, assigned to investigate the destructive invasions of Cliona’s bungalow, and the source of some comic relief during the near-apocalyptic finale. McClelland represents the skeptical realist, forced slowly to recognize the fantastical nature of the events he has witnessed, helping to keep the fantasy grounded: “’Guess something’s wrong,’ conceded the detective heavily. ‘Any man who keeps an illuminated boa constrictor like that in his gate lodge will bear looking at.’”

Possibly attracted by the idol, which Colin had given to Cliona, strange visitations of her home begin to take place, escalating in violence and destructiveness. Colin discovers that he source of the late-night marauders may be the estate of the mysterious Chester Reed, an exotic animal breeder recently established in the neighborhood, and who seems strangely familiar to O’Hara upon their meeting. Getting to the bottom of the mystery, Colin, Cliona, and her husband are abetted by Detective McClelland, assigned to investigate the destructive invasions of Cliona’s bungalow, and the source of some comic relief during the near-apocalyptic finale. McClelland represents the skeptical realist, forced slowly to recognize the fantastical nature of the events he has witnessed, helping to keep the fantasy grounded: “’Guess something’s wrong,’ conceded the detective heavily. ‘Any man who keeps an illuminated boa constrictor like that in his gate lodge will bear looking at.’”

Reed, the keeper of the illuminated boa constrictor (the spawn of Nacoc-Yaotl often glow with some sort of bioluminescence), as well as other strange hybrid creatures, is presented as a Dr. Moreau-type mad scientist, but his true identity, and the source of his powers, bring the novel full circle back to the dreamlike experiences of O’Hara and Kennedy in Tlapallan:

Between the granite pillars, fungoids and some kind of whitish vegetation like pale rushes grew quickly, but though those fungoids and rushes had a strangeness of their own, it was not the vegetable growth alone which made Reed’s marsh peculiar. Its entire space was acrawl with living forms that for repulsiveness could only be compared to a resurgence from their graves of creatures dead and half-decayed… From the pale blob of a thing that lurched past on a bunch of tentaclelike legs, to a creature so buried in mire that only its bony head lay on the surface like the yellowed skull of a horse, all [the creatures in the marsh] were hideous… It was not their ugliness that frightened Colin. It was their eyes. Venomous, intelligent, unforgettable, that which looked through them was far removed from the innocent ferocity of wild beasts. They were goblins!

The Citadel of Fear is an impressive accomplishment: pulp weird fantasy, with vividly fantastic prose, as in some of the passages I’ve quoted, but also carefully controlled. The plot incorporates a dozen disparate elements, yet is achieves unity, with no loose threads. Bennett’s return of Kennedy and Biornsen to the story in the final third of the novel manages to seem both unexpected and inevitable. For anyone who hasn’t read pulp fantasy from this era, Bennett’s 1918 novel would be a great introduction. She combines lost world fantasy with (pre-Lovecraft) Lovecraftian horror and Wellsian science fiction in a way that would become increasingly unusual once these three genres went in separate directions with the development of the specialized pulps from the 1920s through the 1940s. The Citadel of Fear has all the fun of the early pulps, without many of the excesses which sometimes make pulp writing from this period unpalatable today. Given her position historically, and the nature of this novel, it’s clear that Gertrude Barrows Bennett/Francis Stevens deserves recognition both for her place in the development of weird fantasy, and for her writings themselves, which remain highly entertaining in a way that many of her contemporaries’ works no longer do.

The Citadel of Fear is an impressive accomplishment: pulp weird fantasy, with vividly fantastic prose, as in some of the passages I’ve quoted, but also carefully controlled. The plot incorporates a dozen disparate elements, yet is achieves unity, with no loose threads. Bennett’s return of Kennedy and Biornsen to the story in the final third of the novel manages to seem both unexpected and inevitable. For anyone who hasn’t read pulp fantasy from this era, Bennett’s 1918 novel would be a great introduction. She combines lost world fantasy with (pre-Lovecraft) Lovecraftian horror and Wellsian science fiction in a way that would become increasingly unusual once these three genres went in separate directions with the development of the specialized pulps from the 1920s through the 1940s. The Citadel of Fear has all the fun of the early pulps, without many of the excesses which sometimes make pulp writing from this period unpalatable today. Given her position historically, and the nature of this novel, it’s clear that Gertrude Barrows Bennett/Francis Stevens deserves recognition both for her place in the development of weird fantasy, and for her writings themselves, which remain highly entertaining in a way that many of her contemporaries’ works no longer do.

[If looking for a copy of The Citadel of Fear, be aware that most of the e-books based on public domain sources are incomplete, containing only the first two thirds of the novel (twenty of the thirty-one chapters), a problem that the publishers of these versions seem unaware of. A reasonably well-proofed and complete online version can be found here.]

Full Details

Full Details

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.