The Universe Wants You Dead: The Return of Cosmic Horror

It’s a phrase I expect to find written in fat, drippy letters on the cover of an EC comic book from the 1950’s. Or one of the empty promises hurled at the audience in the previews for what will prove to be a predictably ordinary 1940’s horror film: Fiendish Tortures!… Ghastly Terrors!!… Cosmic Horror!!!

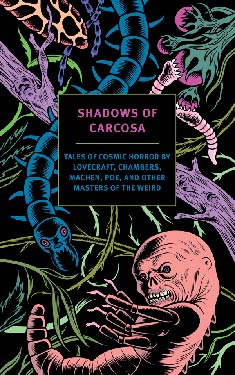

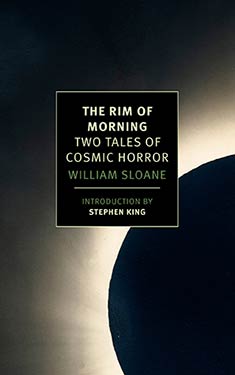

It is not a term I expect to find in the subtitle of not one but two current releases from New York Review Book Classics – Shadows of Carcosa, Tales of Cosmic Horror edited by D. Thin; and, The Rim of Morning, Two Tales of Cosmic Horror by William Sloane. NYRB Classics is an admirably eclectic sampling of world literature where major if obscure works of European Modernism find themselves shelved alongside noirish crime fiction of both U.S. and European vintages and the novels, memoirs and travel journals of excellent prose stylists who the editors have rightly decided deserve a fresh hearing.

But “Cosmic Horror”?

First of all, what are they talking about? And are they just trying to avoid the even pulpier term, Weird Fiction, which is, by the way, what they are talking about. Weird Fiction found its home in the classic pulp magazine Weird Tales. That magazine had a long run from 1923 – 1954 and several incarnations since, one of which remains in print. Hundreds of authors, many lost to time, appeared in the magazine, but it remains best known for the presence of H.P. Lovecraft in its early issues.

First of all, what are they talking about? And are they just trying to avoid the even pulpier term, Weird Fiction, which is, by the way, what they are talking about. Weird Fiction found its home in the classic pulp magazine Weird Tales. That magazine had a long run from 1923 – 1954 and several incarnations since, one of which remains in print. Hundreds of authors, many lost to time, appeared in the magazine, but it remains best known for the presence of H.P. Lovecraft in its early issues.

Although Lovecraft acknowledged his many forbearers, his florid, visionary style defined the genre. This new NYRB anthology quotes him on the back cover. He writes that in the true weird tale —

An atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; a hint of that most terrible conception of the human brain – a malign and particular suspension of defeat of those fixed laws of nature what are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.

Lovecraft’s was a cosmic vision, and later writing on the genre introduced and refined the term “cosmic horror.” A Wikipedia entry covers the field but has the unfortunate term “comicism” as a title. The website TV Tropes takes a more casual and entertaining approach. They offer a five-question quiz readers can use when confronting possible entries to the cosmic horror canon. Two negative answers means that you have slipped into the watered down realm of “Lovecraft Lite.”

With the first season of the HBO series True Detective, the Cosmic Horror genre wormed its way into the minds of a great swath of the American public that had probably never considered reading Lovecraft or Weird Fiction. The ritualistic murders and the decadent sect that the protagonists uncovered in the American South made references to The King in Yellow and Carcosa. Viewers and commentators rushed to the internet to unpack those references and found the peculiar 1895 work by R.W. Chambers, a popular if not particularly good writer of the time who specialized in romance novels but turned out several anthologies of weird fiction. In Chamber’s work, The King in Yellow is the name of a forbidden play, a work so diabolical that reading it, particularly reading Act Two, will drive a person mad. The play is set in Carcosa, an imaginary city Chambers borrowed from an 1891 Ambrose Bierce short story. The HBO series employs the terms divorced from any of their previous fictional uses, but weirdness and cosmic horror is all about hints and evocations. True Detective’s grand guignol set pieces and its pessimistic denouement did the tradition proud.

Shadows of Carcosa includes both the Bierce short story and a tale from the Chambers collection. It’s a chronological anthology that begins with Edgar Allan Poe and ends with Lovecraft, therefore much of what is here is “proto-weird.” It’s a progression of established tales that allows editor D. Thin to make a case for a genuine tradition. Genre fans will find mostly familiar material with a few hard-to-come-by entries, and such terror masterpieces as Poe’s “MS Found in a Bottle” or Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” are always worth rereading in a new context. For people only familiar with Dracula, Bram Stoker’s “The Squaw” proves that he was a refined purveyor or Victorian frights that had found their way into a more modern world than their Gothic predecessors. Arthur Machen is an enthusiasm I have long aspired to without ever quite attaining, but rereading “The White People” makes me want to have another go at him. Including Henry James and Walter de la Mare may be a stretch for the editor, but I am not one to complain given the quality of their stories.

This was my first encounter with M.P. Shiel, who I know wrote The Purple Cloud (1901), an apocalyptic novel kept in print by Penguin Classics. “The House of Sounds,” his story collected here, is an off-the-rails variation on the theme of a young man’s journey to the remote home of an old college friend. I am not surprised to learn that his contemporaries considered Shiel “gorgeously mad,” and that he had become a “reclusive religious maniac” by the time of his death.

Prose as feverish as Shiel’s or Lovecraft’s, and situations as extreme as those that fill these stories, ask the committed reader not to find the enterprise ridiculous. The writing at its best, or at its worst – these terms can become relative – may be bonkers, but woven through the lurid fireworks are passages effective as both visceral horror and exciting of explorations of extreme psychological states. The diarist in Poe’s “MS Found in a Bottle” is trapped on a ship blown off course and headed for oblivion. His lucidity is the last remnant of his humanity.

To conceive the horror of my sensations is, I presume, utterly impossible; yet a curiosity to penetrate the mysteries of these awful regions predominates even over my despair, and will reconcile me to the most hideous aspect of death. It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge – to some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction.

To conceive the horror of my sensations is, I presume, utterly impossible; yet a curiosity to penetrate the mysteries of these awful regions predominates even over my despair, and will reconcile me to the most hideous aspect of death. It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge – to some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction.

The two William Sloane novels from the 1930’s gathered in The Rim of Morning may seem like tame stuff compared to the stories in D. Thin’s anthology. To Walk the Night and The Edge of Running Water were Sloane’s only two novels. He wrote a few stories, edited a couple of significant sf anthologies, but spent most of his career as the director of Rutgers University Press. Stephen King writes the admiring introduction to the NYRB volume, and he lets the reader know not to anticipate the kind of horror show that we have come to expect from the genre:

Sloane builds his stories in carefully wrought paragraphs, each one clear and direct. He is a man of the old school, who learned actual grammar in grammar school…and probably Latin at the high school and college levels.

King may be weeding out the sensation seekers, but, like King, I was hooked by the first sentence of each of Sloane’s novels. These openings promise the kind of storytelling I weaned myself on as a child and still find irresistible.

The form in which this narrative is cast must necessarily be an arbitrary one. In the main it follows the story pieced together by Dr. Lister and myself as we sat on the terrace of his Long Island house one night in the summer of 1936.

To Walk the Night

The man for whom this story is told may or may not be alive.

The Edge of Running Water

Sloane’s novels bring in university settings and academic protagonists, which is not surprising given his background. In To Walk the Night, two young men making their way in the New York City financial markets return to their alma mater for a homecoming football game. When they go to visit a favorite astronomy professor, they find him seated in the chair at his telescope in the school’s observatory and burned to a crisp. (Small North Eastern colleges have observatories in these types of stories the same way college professors have elaborate laboratories in their remote country homes – see The Edge of Running Water ff.) The deceased professor had recently acquired, to his ex-students’ surprise, a young, beautiful, otherworldly wife. To the reader’s surprise, when this woman shows up in Manhattan one of the young men falls under her spell, marries her, and moves to the desert. Distressed letters from the young husband brings his friend to Cloud Mesa and sets up Sloane’s final set piece, a conclusion that proves that this director of Rutger’s University Press knew how to put on quite a show.

In The Edge of Running Water, a young science professor answers a distressed message from his mentor who has retired – in disgrace – to some New England backwater. There he continues researches that may change the way we think about life and death. That sounds like the hackneyed plot to some minor, 1940’s Universal Studios Boris Karloff vehicle, and in fact it is. You can stream it on Your Tube under its more suitable Saturday matinee title, The Devil Commands. (I recommend it on principle, not having yet watched it myself.) Sloane squeezes all the action of his final novel into a forty-eight-hours and incorporates a love interest for the young protagonist, a creepy medium whose agenda may run counter to the aging professor’s best interests, and a possible murder. What the novel lacks in suspense it makes up for in characterization and a frenzied conclusion. Sloane’s novels may appeal to only a small segment of the horror market, but they definitely have their place in the history of American fantastic literature. They are best read on rainy afternoons.

NYRB Classics have sprinkled horror and science fiction through their lists, and these two volumes are welcomed additions. Two new titles do not mark a trend, but given the depth and quality of their crime list, weird fiction, cosmic horror, or however they choose to label it is a promising field should they choose to commit to it.

Full Details

Full Details

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.