Reading the Pulps #4: “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” by David H. Keller, M.D.

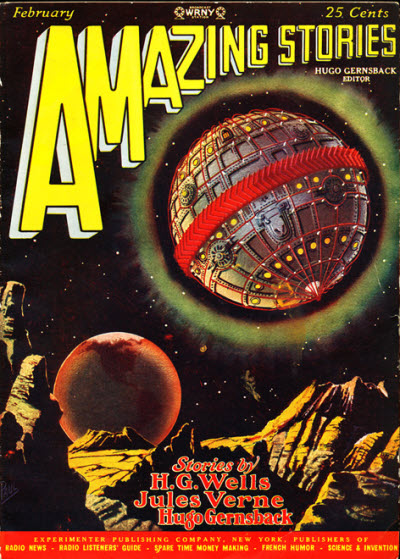

Read it now: Amazing Stories February 1928 (from the Luminist League)

You might already own “The Revolt of the Pedestrian” in one of these anthologies:

- The Road to Science Fiction #2: From Wells to Heinlein edited by James Gunn

- Amazing Stories: 60 Years of the Best Science Fiction edited by Asimov/Greenberg

- The Twelfth Golden Age of Science Fiction Megapack (.99 cent ebook)

- The Best of Amazing Stories: The 1928 Anthology ($2.99 ebook)

Warning: This column contains spoilers.

If you only read science fiction for entertainment you could find “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” entertaining enough, especially if you get a hoot out of old-fashioned science fiction. A quick reading might suggest it’s a silly story, but I believe under the surface it has a number of nasty streaks. We generally think of science fiction as cheerleading for the final frontier. Reading “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” shows David H. Keller promoting something else.

My purpose in analyzing this tale is to show that science fiction wanted to be more than just entertainment. Science fiction can’t take itself too seriously because the genre is burdened by the prejudice that it’s not. However, some science fiction writers wanted to distinguish themselves by using science fiction to say something serious about society. The gold medal example of this is Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell. Keller wins no medal though.

It is often assumed science fiction began genre in April of 1926 with the first issue of Amazing Stories edited by Hugo Gernsback. But that first issue was all reprints, with stories from 1845-1923, suggesting that science fiction had already been around at least 83 years. David H. Keller M.D. (1880-1966) was one of Gernsback early writers, and “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” was his first short story for Amazing. Few readers remember Keller or this story today

Hugo Gernsback took science fiction very seriously. “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” is an example of what Gernsback wanted: speculation, and extrapolation. Keller’s story isn’t much of a story as a polemic against mechanization if we are to assume Keller was serious. He could have gotten its idea on a whim, hoping to make a few bucks at a new magazine about the future. On the other hand, I think he was expressing his conservative views.

What I’d love to know is how Americans thought of science fiction in 1928. The term wasn’t in use yet, as Gernsback wanted to call his stories scientifiction – a tongue twister that would never be accepted. Stories involving travel to other planets had been around for a while, but only in journals and books that few people read.

On January 7, 1929, the Buck Rogers comic strip began running in newspapers. That comic strip was read by millions, and with the 1934 Flash Gordon strip, they probably spread science fictional ideas too far more Americans than Amazing Stories ever did. Buck Rogers originally appeared in Amazing Stories as a short story, but I’ve read so few stories from Gernsback Amazing to know if it was typical. Buck Rogers in the comic strip and serial was silly, even campy, which suggests it’s where the prejudice that science fiction wasn’t serious began. People used to call science fiction, “That crazy Buck Rogers stuff.”

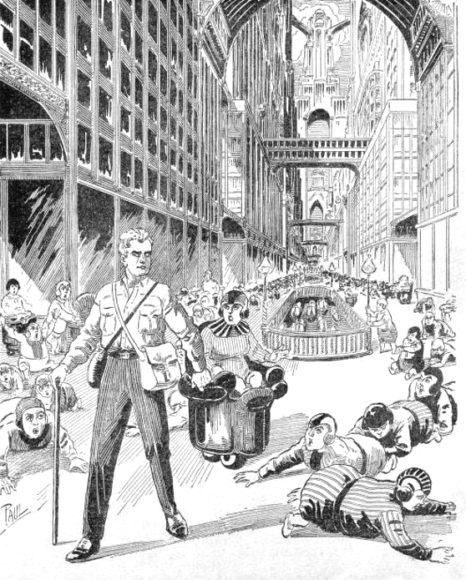

“The Revolt of the Pedestrians” is set many centuries in the future after humans divide into two species – the pedestrians and the automobilists. Automobilists have shrunken legs from always using automobiles or powered chairs called autocars. Eventually, the overwhelming majority of society become automobilists and decide pedestrians are anti-progress — a threat to society. They are outlawed, killed and assumed extinct.

Most of Keller’s story is narrative. There is very little drama or action. Keller may have gotten his central idea from The Time Machine by H. G. Wells, where humanity splits into two opposing species. I find it especially hard to believe that Keller thought automobiles were bad for humanity, or it would cause humans to devolve their legs. Logically, he should have known we spend far more time not using cars. Nor could a few centuries have caused the changes he suggests.

I believe Keller was writing about a divide in humanity in his own day, between conservatives and liberals. David H. Keller is now remembered as having been an extreme right-wing, anti-feminist, and racist. Cars and voting women were still new in 1928. Within the story, Keller also expresses pro-eugenic and pro-euthanasia ideas that were also common in the 1920s. The society of the automobilists is seen as socialist and scientific, whereas the rebelling pedestrians are advocates of back to nature and rugged individualists. Hating the automobilists they invent a kind of EMP device to switch-off technological society, thus killing billions of automobilists.

This isn’t escapist fun, but a vicious view. In a way, it prefigures Brave New World by Aldous Huxley that came out in 1932. “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” is an early dystopia. Why would Gernsback accept an anti-science, anti-technology story for Amazing Stories?

The story comes down to a battle between two families, and two men, the pedestrian Abraham Miller and the automobilist William Henry Heisler. They were even distant cousins, and an ancestor of Miller was killed by a distant ancestor of Heisler. The son of that slain victim works for generations to revenge the pedestrians.

For me, the story only had two engaging characters. Margaretta Heisler, child of the automobilist, is a biological throwback who has working legs. Because William Henry Heisler is rich he protects his daughter from being destroyed.

After that conversation, Heisler engaged the old man, whose sole duty was to investigate the subject of pedestrian children and find how they played and used their legs. Having investigated this, he was to instruct the little girl.

The entire matter of her exercise was left to him. Thus from that day on a curious spectator from an aeroplane might have seen an old man sitting on the lawn showing a golden-haired child pictures from very old books and talking together about the same pictures. Then the child would do things that no child had done for a hundred years—bounce a ball, skip rope, dance folk dances and jump over a bamboo stick supported by two upright bars. Long hours were spent in reading and always the old man would begin by saying:

“Now this is the way they used to do.”

Occasionally a party would be given for her and other little girls from the neighboring rich would come and spend the day. They were polite—so was Margaretta Heisler—but the parties were not a success. The company could not move except in their autocars, and they looked on their hostess with curiosity and scorn. They had nothing in common with the curious walking child, and these parties always left Margaretta in tears.

“Why can’t I be like other girls?” she demanded of her father. “Is it always going to be this way? Do you know that girls laugh at me because I walk?”

Heisler was a good father. He held to his vow to devote one hour a day to his daughter, and during that time gave of his intelligence as eagerly and earnestly as he did to his business in the other hours. Often he talked to Margaretta as though she were his equal, an adult with full mental development.

“You have your own personality,” he would say to her. “The mere fact that you are different from other people does not of necessity mean that they are right and you are wrong. Perhaps you are both right—at least you are both following out your natural proclivities. You are different in desires and physique from the rest of us, but perhaps you are more normal than we are. The professor shows us pictures of ancient peoples and they all had legs developed like yours. How can I tell whether man has degenerated or improved? At times when I see you run and jump, I envy you. I and all of us are tied down to earth—dependent on a machine for every part of our daily life. You can go where you please. You can do this and all you need is food and sleep. In some ways this is an advantage. On the other hand, the professor tells me that you can only go about four miles an hour while I can go over one hundred.”

“But why should I want to go so fast when I do not want to go anywhere?”

“That is just the astonishing thing. Why don’t you want to go? It seems that not only your body but also your mind, your personality, your desires are old-fashioned, hundreds of years old-fashioned. I try to be here in the house or garden every day—at least an hour—with you, but during the other hours I want to go. You do the strangest things. The professor tells me about it all. There is your bow and arrow, for instance. I bought you the finest firearms and you never use them, but you get a bow and arrow from some museum and finally succeed in killing a duck, and the professor said you built a fire out of wood and roasted it and ate it. You even made him eat some.”

“But it was good, father—much better than the synthetic food. Even the professor said the juice made him feel younger.”

Heisler laughed, “You are a savage—nothing more than a savage.”

“But I can read and write!”

“I admit that. Well, go ahead and enjoy yourself. I only wish I could find another savage for you to play with, but there are no more.”

“Are you sure?”

“As much so as I can be. In fact, for the last five years my agents have been scouring the civilized world for a pedestrian colony. There are a few in Siberia and the Tartar Plateau, but they are impossible. I would rather have you associate with apes.”

“I dream of one, father,” whispered the girl shyly. “He is a nice boy and he can do everything I can. Do dreams ever come true?”

Heisler smiled. “I trust this one will, and now I must hurry back to New York. Can I do anything for you?”

“Yes—find someone who can teach me how to make candles.”

“Candles? Why, what are they?”

She ran and brought an old book and read it to him. It was called, “The Gentle Pirate,” and the hero always read in bed by candle light. “I understand,” he finally said as he closed the book. “I remember now that I once read of their having something like that in the Catholic churches. So you want to make some? See the professor and order what you need. Hum—candles—why, they would be handy at night if the electricity failed, but then it never does.”

“But I don’t want electricity. I want candles and matches to light them with.”

“Matches?”

“Oh, father! In some ways you are ignorant. I know lots of words you don’t, even though you are so rich.”

“I admit it. I will admit anything and we will find how to make your candles. Shall I send you some ducks?”

“Oh, no. It is so much more fun to shoot them.”

“You are a real barbarian!”

“And you are a dear ignoramus.” So it came to pass that Margaretta Heisler reached her seventeenth birthday, tall, strong, agile, brown from constant exposure to wind and sun, able to run, jump, shoot accurately with bow and arrow, an eater of meat, a reader of books by candlelight, a weaver of carpets and a lover of nature. Her associates had been mainly elderly men: only occasionally would she see the ladies of the neighborhood. She tolerated the servants, the maids and housekeeper. The love she gave her father she also gave to the old professor, but he had taught her all she knew and the years had made him senile and sleepy.

The other character I cared for was a pedestrian man who dressed as a woman working as a stenographer so he could spy on automobilist Heisler. This is a short scene, and almost an aside to the main story, so I wondered why Keller included it. I’m sure Keller was expressing his own prejudices here, but what did Amazing Stories readers make of this scene?

But for the first time in his life, he was in a big city. The firm on the floor below employed a stenographer. She was a very efficient worker in more ways than one and there was that about the new stenographer that excited her interest. They met and arranged to meet again. They talked about love, the new love between women. The spy did not understand this, having never heard of such a passion, but he did understand eventually, the caresses and kisses. She proposed that they room together, but he naturally found objections. However, they had spent much of their spare time together. More than once the pedestrian had been on the point of confiding in her, not only the impending calamity, but also his real sex and his true love.

In such cases where a man falls in love with a woman the explanation is hard to find. It is always hard to find. Here there was something twisted, a pathological perversion. It was a monstrous thing that he should fall in love with a legless woman when he might by waiting, have married a woman with columns of ivory and knees of alabaster. Instead, he loved and desired a woman who lived in a machine. It was equally pathological that she should love a woman. Each was sick—soulsick, and each to continue the intimacy deceived the other. Now with the city dying beneath him, the stenographer felt a deep desire to save this legless woman. He felt that a way could be found, somehow, to persuade Abraham Miller to let him marry this stenographer—at least let him save her from the debacle.

So in soft shirt and knee trousers he cast a glance at Miller and Heisler engaged in earnest conversation and then tiptoed out the door and down the inclined plane to the floor below. Here all was confusion. Boldly striding into the room where the stenographer had her desk, he leaned over her and started to talk. He told her that he was a man, a pedestrian. Rapidly came the story of what it all meant, the cries from below, the motionless auto-cars, the useless elevators, the silent telephones. He told her that the world of automobilists would die because of this and that, but that she would live because of his love for her. All he asked was the legal right to care for her, to protect her. They would go somewhere and live, out in the country. He would roll her around the meadows. She could have geese, baby geese that would come to her chair when she cried, “Weete, weete.”

The legless woman listened. What pallor there might be in her cheeks was skillfully covered with rouge. She listened and looked at him, a man, a man with legs, walking. He said he loved her, but the person she had loved was a woman; a woman with dangling, shrunken, beautiful legs like her own, not muscular monstrosities.

She laughed hysterically, said she would marry him; go wherever he wanted her to go, and then she clasped him to her and kissed him full on the mouth, and then kissed his neck over the jugular veins, and he died, bleeding into her mouth, and the blood mingled with rouge made her face a vivid carmine. She died some days later from hunger.

When I first read this story back in the early 1970s it just seemed like a silly spoof on evolutionary possibilities. I didn’t contemplate how the central idea would have been stupid even back in 1928. I didn’t think about how it could be a political statement.

The apparent hero of this story, Abraham Miller, is a mass murderer, destroying a world-wide civilization of billions. As part the story we see a city of millions thrown into chaos as its inhabitants try to crawl out of the city. I wonder if Keller wanted us to associate the name Abraham with Lincoln, or the Abraham of the Bible. I associated Abraham Miller with Adolph Hitler.

“The Revolt of the Pedestrians” has not been reprinted often. Few stories from the early days of Amazing Stories have, but reading “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” make me want to read more of those old stories to see what else Gernsback was philosophically promoting. Maybe there are more reasons than financial why Gernsback lost his magazine.

We generally assume science fiction was propaganda for progress, but this story is really a revolt against modernity. I used to think it amusing back in the 1970s when I took courses in the Modern Novel we mostly read books from the 1920s. A tremendous amount of change happened in that decade, and I guess Keller wasn’t too thrilled with them. The 1920s was a huge era for the KKK, with many state governors belonging to that racist organization. And like I mentioned above, Keller promotes eugenics within the story, which had been adopted by some states at that time. I guess Amazing Stories readers just assumed Keller’s ideas were part of the status quo.

Contemporary conservatives often seem anti-science today. Maybe they see liberals as a divergent species. I wonder if we’re still in a civil war over modernity. For the most part, I believe science fiction has taken the side of the Enlightenment, but I need to pay more attention when I read these old science fiction stories for their political philosophy.

Science fiction is always about the times in which it was written. Growing up in the 1960s I assumed science fiction reflected my liberal beliefs for my future, but now that I’m rereading these old stories I realize I had ignored obvious conservative hopes for their future. Since we’re living in a Donald Trump timeline, I wonder if some science fiction helped create it.

JWH

Full Details

Full Details

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.