WoGF Review: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest

Matt W. (Mattastrophic), is a teacher and a PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition in Kentucky. SF is his literary indulgence, his escape from dissertation writing, and the subject of an occasional conference presentation. His blog, Strange Telemetry, is both his sounding board and his chronicle as he makes his way through the various sub-genres of SF in order to better understand his tastes as a reader and the craft of writing in general.

Matt W. (Mattastrophic), is a teacher and a PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition in Kentucky. SF is his literary indulgence, his escape from dissertation writing, and the subject of an occasional conference presentation. His blog, Strange Telemetry, is both his sounding board and his chronicle as he makes his way through the various sub-genres of SF in order to better understand his tastes as a reader and the craft of writing in general.

It is the late 19th century. The American Civil War has carried on for over a decade, and the America’s northwestern territories are mostly left to fend for themselves. On a commission from the Russian government, inventor Leviticus Blue creates a mighty machine, the Boneshaker, whose drill was intended to pierce the tough rock and permafrost in the vast oil fields of the Alaskan territories. Before its unveiling, however, Blue’s machine was turned on. The Boneshaker tore through his laboratory and through the underground of a great chunk of Seattle, in what would later become the state of Washington. Buildings collapsed, people and structures fell into massive sinkholes, and a noxious gas that turned people into rotting, cannibalistic monsters was released. Panic ensued, and in the confusion a well-respected lawman, Maynard Wilkes, went into the heart of the blight-gassed streets and released a mass of prisoners, possibly to help him take advantage of the chaos and rob the now-vulnerable banking district. Well, Wilkes died, Blue disappeared, and a great wall went up around downtown Seattle to cordon off the blight-filled streets and the rotters, the living dead, who now dwelt there.

It is the late 19th century. The American Civil War has carried on for over a decade, and the America’s northwestern territories are mostly left to fend for themselves. On a commission from the Russian government, inventor Leviticus Blue creates a mighty machine, the Boneshaker, whose drill was intended to pierce the tough rock and permafrost in the vast oil fields of the Alaskan territories. Before its unveiling, however, Blue’s machine was turned on. The Boneshaker tore through his laboratory and through the underground of a great chunk of Seattle, in what would later become the state of Washington. Buildings collapsed, people and structures fell into massive sinkholes, and a noxious gas that turned people into rotting, cannibalistic monsters was released. Panic ensued, and in the confusion a well-respected lawman, Maynard Wilkes, went into the heart of the blight-gassed streets and released a mass of prisoners, possibly to help him take advantage of the chaos and rob the now-vulnerable banking district. Well, Wilkes died, Blue disappeared, and a great wall went up around downtown Seattle to cordon off the blight-filled streets and the rotters, the living dead, who now dwelt there.

WoGF Review: Zoo City by Lauren Beukes

Matt W. (Mattastrophic), is a teacher and a PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition in Kentucky. SF is his literary indulgence, his escape from dissertation writing, and the subject of an occasional conference presentation. His blog, Strange Telemetry, is both his sounding board and his chronicle as he makes his way through the various sub-genres of SF in order to better understand his tastes as a reader and the craft of writing in general.

Matt W. (Mattastrophic), is a teacher and a PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition in Kentucky. SF is his literary indulgence, his escape from dissertation writing, and the subject of an occasional conference presentation. His blog, Strange Telemetry, is both his sounding board and his chronicle as he makes his way through the various sub-genres of SF in order to better understand his tastes as a reader and the craft of writing in general.

What if your guilt was visible for everyone to see? Suppose your crimes actually granted you special powers, like some inverted superhero story. Would the powers be worth being set apart from the rest of humanity, or would the magic only make that isolation worse?

What if your guilt was visible for everyone to see? Suppose your crimes actually granted you special powers, like some inverted superhero story. Would the powers be worth being set apart from the rest of humanity, or would the magic only make that isolation worse?

Zoo City, winner of the 2011 Arthur C. Clarke Award, follows former journalist Zinzi December. Zinzi has been isolated from much of humanity due to the baggage she carries: a lingering drug habit, massive debt to her dealer, a bad email scam habit, guilt for her brother’s death, and a sloth. Zinzi is one of the animalled, or a “Zoo,” and her sloth marks her as a criminal. Her connection to her sloth is magical, granting her the power to find lost things. It’s also terminal, meaning that when she or it dies the Undertow will come for her and literally drag her kicking and screaming into the dark.

Zoo familiars come in all forms–mongooses, snakes, tigers, monkeys, scorpions, etc.–with a variety of special gifts and powers. In Johannesburg, South Africa, they are segregated into a run-down ghetto called Zoo City (based on the “gray area” of the Hillbrow district of Johannesburg). Shunned by most normals, Zoos have to get by however they can. Zinzi, playing the Marlowe-esque character, is hired by a reclusive music executive to find the female half of a pair of twin teenie Afro-pop stars. The problem is she doesn’t find lost people, only lost things, and her problems are compounded by the shadiness of her employers. Her search will find her combing the dregs of Johannesburg and Zoo City, making connections with the shattered remains of her former life, struggling to cope with her debt and her flaws, all the while with Sloth on her back, non-verbally chiding her.

WoGF Review: Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood

Matt W. (Mattastrophic), is a teacher and a PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition in Kentucky. SF is his literary indulgence, his escape from dissertation writing, and the subject of an occasional conference presentation. His blog, Strange Telemetry, is both his sounding board and his chronicle as he makes his way through the various sub-genres of SF in order to better understand his tastes as a reader and the craft of writing in general.

Matt W. (Mattastrophic), is a teacher and a PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition in Kentucky. SF is his literary indulgence, his escape from dissertation writing, and the subject of an occasional conference presentation. His blog, Strange Telemetry, is both his sounding board and his chronicle as he makes his way through the various sub-genres of SF in order to better understand his tastes as a reader and the craft of writing in general.

Oryx and Crake is told in the third person and it alternates between the past and present of Snowman, the last normal human survivor of an apocalyptic plague. Snowman is sworn to watch over the “Crakers,” bio-engineered humans created by his childhood friend Crake. Snowman is very much alone, however, since the Crakers are very naive and have had many human traits (like love and the need to eat animal meat) bypassed in their design. Snowman whiles away the time reminiscing about his previous life, when he was known as Jimmy.

Oryx and Crake is told in the third person and it alternates between the past and present of Snowman, the last normal human survivor of an apocalyptic plague. Snowman is sworn to watch over the “Crakers,” bio-engineered humans created by his childhood friend Crake. Snowman is very much alone, however, since the Crakers are very naive and have had many human traits (like love and the need to eat animal meat) bypassed in their design. Snowman whiles away the time reminiscing about his previous life, when he was known as Jimmy.

Jimmy grew up under the domes of mega-corporations, segregated from the poverty-stricken, disease-ridden plebeians. Disregarded by his father (a corporate genetic engineer) and abandoned by his mother (who leaves him to become a corporate saboteur), Jimmy befriends Crake, a boy genius who grows up to become a leading corporate bio-engineer. The story of Snowman/Jimmy is told as he wanders the wastes of civilization, pondering his relationships with Crake and with Oryx (former child prostitute, teacher of the Crakers, and lover of both Jimmy and Crake), and trying to reconcile the events that brought him and the rest of humanity over the precipice.

GMRC Review: Non-Stop by Brian Aldiss

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed.

Published in 1958, Non-Stop (a.k.a. Starship in the UK printing) was Brian Aldiss’ first novel, and it uses as its central conceit that well-trodden SF trope, the generation ship. These are enormous, self-sustaining star-ships that can house and support multiple generations of humans living within them as the ship makes its slow way from one star to another. Only the first generation will know Earth, and only the last ones will know their destination; the middle generations will know only the ship. Barring faster-than-light travel or some form of suspended animation, this is the only way for humans to effect interstellar travel. The idea was posited in the late 1920′s/early 1930′s, and has appeared often throughout SF, and 2009′s Pandorum and Mary Robinnette Kowal’s 2011 Hugo-Award-winning short story “For Want of a Nail” (a very good story, I might add), show that there is still traction and interest in this well-worn trope. Of course, the ubiquitous element of the generation star-ship sub-genre is that something goes terribly wrong during the voyage. In the early 1940′s, Heinlein published two stories (later collected into Orphans of the Sky) about a generation starship in which the middle generations of the generation ship have forgotten that they are on a starship, since it is the only world they know, causing shipboard society to erode into a more primitive, superstitious state. Aldiss, loved the concept, but disliked Heinlein’s execution, and Non-Stop is his response.

Published in 1958, Non-Stop (a.k.a. Starship in the UK printing) was Brian Aldiss’ first novel, and it uses as its central conceit that well-trodden SF trope, the generation ship. These are enormous, self-sustaining star-ships that can house and support multiple generations of humans living within them as the ship makes its slow way from one star to another. Only the first generation will know Earth, and only the last ones will know their destination; the middle generations will know only the ship. Barring faster-than-light travel or some form of suspended animation, this is the only way for humans to effect interstellar travel. The idea was posited in the late 1920′s/early 1930′s, and has appeared often throughout SF, and 2009′s Pandorum and Mary Robinnette Kowal’s 2011 Hugo-Award-winning short story “For Want of a Nail” (a very good story, I might add), show that there is still traction and interest in this well-worn trope. Of course, the ubiquitous element of the generation star-ship sub-genre is that something goes terribly wrong during the voyage. In the early 1940′s, Heinlein published two stories (later collected into Orphans of the Sky) about a generation starship in which the middle generations of the generation ship have forgotten that they are on a starship, since it is the only world they know, causing shipboard society to erode into a more primitive, superstitious state. Aldiss, loved the concept, but disliked Heinlein’s execution, and Non-Stop is his response.

The story follows Roy Complain, a hunter for the nomadic Greene Tribe that crawls its way through the vine-filled decks and hallways, slashing the ‘ponics, looting the rooms they come across, and leaving nothing useful in their wake to dissuade competitors. Roy has prospects, and life seems pretty decent: the tribe eats well, everyone adheres to the religion of Psychology, and he has hopes of being elevated from hunter to guard (giving him access the prime loot). But then his mate bugs him to come on a hunting trip with him, and she is captured by a neighboring tribe. Shamed and angry, Complain questions his place in the tribe and the tribe’s place in the grand scheme of things and so joins a renegade Priest named Marapper along with a handful of Greene tribesman on a wild adventure through unexplored corridors. Their goal is to find the fabled civilization of Forwards, and eventually the Captain of the ship. Of course, Roy doesn’t believe that his world is really a ship, but strange things happen along the way that shake his beliefs in who he is, why he is there, and who he can trust.

Non Stop Adventure: What Non-Stop Does Well

Non-Stop really doesn’t stop; it’s a brisk novel that rarely drags, which works both for and against the narrative. This pace benefits the narrative in that it keeps things interesting by keeping them moving: you can count on something new always lurking just around the bend. There is plenty of action, particularly towards the end, where the novel takes on a frenzied pace and bulls it’s way to the final conceptual breakthrough or revelation.

Actually, knowing that they are on a generation ship is a revelation Roy has later on and thus a kind of minor spoiler (sorry, dear readers), but A) that twist is general knowledge in regards to this novel and B) Aldiss includes plenty of other big surprises that make what happened to the ship just as interesting as what it is, if not more so. The characters know some things about the ship and the artifacts they find, but many truths about their environment have been lost to time and strife among the survivors. It’s interesting to note “the givens,” which are the things that the characters take for granted about their surroundings and how they interact with it. No one sees anything wrong in the hydroponically-grown plants that have burst their confines and overtaken most of the ship. The regularity of their environment (decks, doorways, overhead lighting) is seen as a part of nature. Indeed, when one character finally sees a real sun, he remarks that he expected it to be square just like a giant version of one of the lights within the ship. Aldiss paints a fairly restrictive, claustrophobic picture of life on the ship throughout the novel, which adds nicely to the sense of menace and paranoia built into the plot. I think I might wig out and run amok (which some characters do) due to the unceasing regularity of the environment only broken up by the thick, choking vines. The star-ship is a familiar, orderly setting that is defamiliarized and rendered strange in Aldiss’ work.

The early part of the novel has the strongest sociological speculation in it which, sadly, the story moved away from it fairly quickly to keep things moving. The way the Greene tribe is organized, the rituals and social structures they have developed, were very interesting to me as it illustrated how the people of the ship have adapted to their environment and to the needs of survival while maintaining a semblance of sanity and happiness. For example, children are weaned away from parents and siblings very early, partly, I expect, due to the ersatz religion of psychology (which enshrines consciousness as defined by Freud and Jung) but also to dissuade large families and keep the population manageable. Men don’t meet each other’s eyes, and the common greeting is “Expansion to your Ego,” with the response being “at your expense,” as an explicit albeit civil representation of the psychological power games of respect and abasement we all play. It was interesting and I had hoped for more, but for what it was I enjoyed it.

The characters held a lot of promise in the beginning for me. Roy Complain ultimately reads like a a violent, fairly unremarkable, knuckle-dragging hunter/warrior, but early on he piqued my interest with his encroaching existential crisis: why am I here, why are we here, who are we, what is this place, really? His band of adventurers seemed like a nice mix as well: the uptight Valuer (merchant/trader), the twitchy warrior, the secretive storyteller, and, most intriguing of all, the power-hungry and opportunistic priest Marapper. Marapper is a great character to love and hate: he is devious, backstabbing, dishonest, and alternately self-aggrandizing and self-abasing (whichever benefits him most at the moment).

Overall, what I enjoyed most from this novel was the growing sense of claustrophobia and menace that underlies the exploration of this familiar setting (the starship) rendered strange through the characters’ limited understanding of their environment. This ominous atmosphere was at its prime when the non-human creatures start to appear, some of which really creeped me out (I have a problem with moths, so moths with psychic powers in a confined, claustrophobic space makes me feel uncomfortable to say the least). The action and revelations kept a brisk pace and didn’t let things drag much, and early on in particular the ways in which Complain wrestles with the outward pressures of the tribe and the inward pressures compelling him to leave and discover what is really going on were palpable and helped me sympathize with him a great deal.

Complaints for Complain: Where Non-Stop Could Have Been Better

I found myself frequently frustrated at the inconsistencies in the book’s sociological/phenomenological perspective. To provide an example, early on in the book, Marapper reads aloud from a technical manual he found and Roy doesn’t understand much of what he is hearing (he only knows the syllables), but later Roy and his love interest read through the Captain’s diary without linguistic difficulty even though they are separated from the author by many, many societal decay generations. Which is it, can they read or not? Also, Aldiss frequently uses contemporary cliches or turns of phrase that are way too out of place for the third-person limited perspective of Roy Complain. The best articulation I found of this was from a review on the website Geek Chocolate:

While not unintelligent, the tribes are most certainly uneducated, and told from Complain’s point of view, the novel should reflect this, yet the reader’s vicarious rendering is described using vocabulary that would be beyond his comprehension. “The tight spiralling traced by the rifling in the barrel” would be meaningless to him, as the only projectile weapon the tribes have is bow and arrow, and he is likely similarly ignorant of ancient Greek musical notation, yet apparently the atmospheric systems sound “like a proslambanomenos implementing a sustained chord.”

Aldiss’ writing is good and heart-wrenching in places, but in a novel of this type–where one culture is encountering another that is significantly different and more advanced–the writing should reflect the phenomenological experience of the characters. For example, we know its just a swimming pool, but to Roy–who hasn’t seen so much water before–it’s an awe-inspiring ocean, and the narrative should help us experience that with Roy. It does in places, but inconsistencies in the tribes’ level of education and technological understanding, and Aldiss’ use of contemporary cliches and turns-of-phrase, pulled me out of the experience of encountering the mystery of the ship as the characters perceive it. This made me feel like the worldbuilding–the construction of the world as the characters understood it–was only half done, or that Aldiss was defeating himself in trying to evoke the strange with familiar, contemporary narrative devices.

While I had great enthusiasm for the characters in the beginning, by the end I felt that characterization in this book was fairly flat, which may be the effect of the non-stop, briskly-paced narrative. Roy seems primed to under go some kind of change as his worldviews (literally) are challenged, but he basically remains a predictable, short-tempered hunter-warrior throughout. Aldiss tries to signal a change in Roy that I either didn’t get or that didn’t feel warranted by the narrative. There is one moment when the whole ship is going ape that his love interest, Vyann, reflects that at least he is keeping his humanity and is changing into some kind of better person… at the same moment that Roy, elsewhere, is beating and threatening someone to compel his cooperation. He didn’t change all that much, and thus the character arc was pretty flat and forced if anything. Perhaps this is because the narrative can’t stop to contemplate these changes in more depth and detail, so characters kind of remain in given archetypes. Roy’s love interest, Vyann, begins as a cold, calculating woman who represents the more civilized, advanced people of the Forwards section of the ship, but she melts like butter for Roy. Once again, to quote the review on Geek Chocoloate (because I can’t say it any better): “Laur Vyann, representing the more advanced Forwards section, [is] cold and efficient, yet apparently waiting for the right inbred knuckle-dragger from the rear section of the ship to shamble along and unleash the woman within.” This is a very typical example of the “male gaze,” but one that renders a strong, seemingly complex female character into a simple damsel. By the end, only Marrapper with his barely-contained egoism and opportunism remained interesting to me.

While I had great enthusiasm for the characters in the beginning, by the end I felt that characterization in this book was fairly flat, which may be the effect of the non-stop, briskly-paced narrative. Roy seems primed to under go some kind of change as his worldviews (literally) are challenged, but he basically remains a predictable, short-tempered hunter-warrior throughout. Aldiss tries to signal a change in Roy that I either didn’t get or that didn’t feel warranted by the narrative. There is one moment when the whole ship is going ape that his love interest, Vyann, reflects that at least he is keeping his humanity and is changing into some kind of better person… at the same moment that Roy, elsewhere, is beating and threatening someone to compel his cooperation. He didn’t change all that much, and thus the character arc was pretty flat and forced if anything. Perhaps this is because the narrative can’t stop to contemplate these changes in more depth and detail, so characters kind of remain in given archetypes. Roy’s love interest, Vyann, begins as a cold, calculating woman who represents the more civilized, advanced people of the Forwards section of the ship, but she melts like butter for Roy. Once again, to quote the review on Geek Chocoloate (because I can’t say it any better): “Laur Vyann, representing the more advanced Forwards section, [is] cold and efficient, yet apparently waiting for the right inbred knuckle-dragger from the rear section of the ship to shamble along and unleash the woman within.” This is a very typical example of the “male gaze,” but one that renders a strong, seemingly complex female character into a simple damsel. By the end, only Marrapper with his barely-contained egoism and opportunism remained interesting to me.

The brisk pace of the plot doesn’t only harm characterization, however, as overall plot structure suffers as well. The plot is facilitated by a series of lucky breaks or coincidental revelations that help drive the action and, after a while, felt fairly contrived. The novel moves quickly enough though that it didn’t bother me much as long as I didn’t think about it much, but there were several plot elements that didn’t feel resolved. The big find of the Captain’s diary is just a big data dump that isn’t adequately explored, the threat of the belligerent non-humans doesn’t go beyond being a nuisance, and the conclusion itself feels rather abrupt.

Concluding Thoughts

Despite it’s flaws, I can see why Non-Stop was re-printed in the SF Masterworks series. While the world-building felt inconsistent and the characters half done, Non-Stop is still enjoyable since it maintains a brisk pace, has plenty of action, keeps the discoveries rolling, and houses it all in a menacing but intriguing environment of the starship-turned-wilderness. It’s an interesting exemplar of how sociological concerns play into the generation ship narrative and indeed into all space exploration stories.

Review: The Warded Man by Peter V. Brett

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed. Check out his profile page for more great reviews or visit his blog and let him know you found him here.

Note: The Warded Man is published in the UK as The Painted Man.

The demons rise every night without fail, and every night a few more humans are viciously killed. The only thing that can hold them at bay are the magical wards people put around their homes, and within which they huddle together at night, trying to ignore the sounds of the monsters outside constantly looking for a way in. Some of them find it. When the corelings–demons of fire, rock, air,water, sand, and rot–first rose, they massacred humans close to the point of extinction. Then mankind discovered the magical combat wards that allowed them to fight the beasts. An unparalleled age of science and progress followed, but safety bred complacency, and when the corelings returned mankind fell into a dark age and lost a great deal of knowledge about the wards. Now, during the day men and women work and check their defensive wards, while at night all they can do is huddle in their homes and hope the defenses will hold and keep the monsters out. Travel between townships is minimal, and few know the world beyond their own hometown. Much has been lost, and much continues to be lost as every night as a few more people succumb to the corelings.

The demons rise every night without fail, and every night a few more humans are viciously killed. The only thing that can hold them at bay are the magical wards people put around their homes, and within which they huddle together at night, trying to ignore the sounds of the monsters outside constantly looking for a way in. Some of them find it. When the corelings–demons of fire, rock, air,water, sand, and rot–first rose, they massacred humans close to the point of extinction. Then mankind discovered the magical combat wards that allowed them to fight the beasts. An unparalleled age of science and progress followed, but safety bred complacency, and when the corelings returned mankind fell into a dark age and lost a great deal of knowledge about the wards. Now, during the day men and women work and check their defensive wards, while at night all they can do is huddle in their homes and hope the defenses will hold and keep the monsters out. Travel between townships is minimal, and few know the world beyond their own hometown. Much has been lost, and much continues to be lost as every night as a few more people succumb to the corelings.

Three young people from different towns in this perilous world set off on paths that will eventually converge, and which may eventually lead them to some measure of hope and salvation for mankind. Arlen is a young boy with a knack for wards who has become sick at everyone’s cowardice and lack of resolve to fight the demons. Leesha is a blossoming young woman with a talent for herb gathering and healing, making her a keeper of some of the oldest surviving tradition, lore, and medicine from the days before the corelings return. But a nasty rumor and a town scandal threatens her. Rojer always wanted to be jongleur, a wandering musician and performer who is the delight of every town he passes through (and who brings rare rays of sunshine and joy into this otherwise bleak world). When demons attack his home and he is horribly maimed, that dream is threatened, but eventually he discovers he has a talent for music that goes beyond mere entertainment. Each has been scarred by the demons, and the book follows their growth from childhood to adulthood.

This is the premise of The Warded Man, by Peter V. Brett, which is yet another book that made me think “fah, what crap” when I first saw it. I guess at the time I was put off by what I have noticed is a pretty formulaic title: The (insert adjective here) Man, as in The Demolished Man, The Illustrated Man, The Female Man, The Invisible Man, The Unincorporated Man, The Thin Man, ad inifinitum. Once I got over my title prejudice and took a close gander at the blurb, I was seized by the interesting premise. It put me to mind of the dark ages following the fall of the Roman Empire, when knowledge was lost and the world grew smaller, darker, and scarier, and having just seen a documentary on the dark ages the premise of this book grabbed me at the right moment. After checking out a few reviews of the book, I decided to give it a shot; I had a spare Audible credit at the time, and I was keeping my expectations flexible. To my surprise, I was really sucked into this book, and once again I found that (ugh) you can’t judge a book by its cover (thank you every elementary school teacher I ever had).

Strong Magic: What The Warded Man Does Well

Brett has stated that he really wanted to write a book about fear and it’s effect on people, and in this YouTube interview he links that desire to his experience with 9/11 and it’s aftermath. The fear angle really comes out in this novel. It is strong in the first thread, Arlen’s, where the young boy learns contempt for his own father’s cowardice before the demons. Much of the worldbuilding Brett does revolves around fear of the corelings and the precautions taken to stay safe from them, which fits since it is a constant, pervasive threat in a similar way fear of terrorism swept the U.S. following 9/11. The night is a time of danger and fear for the people of Brett’s novel, so much so that “night!” has become a curse word. Brett has showed how fear of the corelings has affected everything from architecture and city planning to the way cities and societies have become more insular. Messengers, who travel from town to town bearing supplies and act as diplomats and emissaries, are raised to heroic status for braving the open night between towns with nothing but a portable warding circle between them and the monsters. People have become resigned to living in this world, with only one group, the desert people to the south, actively fighting the monsters. Overall, the atmosphere this creates has an appropriate dark ages feel, similar to what happened after the fall of Rome: technology and knowledge has been lost, and the world suddenly grows a lot smaller and a lot scarier.

The characterization is very good as well. Thankfully, it’s is not filler in between action scenes. The demons are catalysts and background for the tragedies and rites of passage that each character struggles with as they grow up, and their circumstances and character arcs makes them feel like distinct, believable characters. I lost myself (in a good way) in the stories of each of the three viewpoint characters, and even when they were not dealing with the demons their stories were still exciting, tense, and interesting. Will Arlen find a way to fight the demons, or is it only a boy’s fantasy? Can he ever settle for a normal life, one with a wife and children? Will Leesha ever get past the stigma put on her by that nasty rumor, and finally be able to move on with her life? Will she ever be rid of her domineering mother? Will Rojer be able to hang on to his dream of being a jongleur given his maimed hand and his now drunkard of a mentor? Their life experiences feel true to the human condition given such an environment, and like George R. R. Martin’s books (which Brett cites as a major inspiration) the situations they are in frequently offer no easy out or simple moral choice. Each viewpoint character feels well-realized, so that when they eventually come together their relationships with one another is dynamic and interesting.

While the characterization is not just filler between the action, that doesn’t mean that the action is disregarded or underdeveloped. The action works pretty well, especially the climax of the book. There are very few ways to fight the demons, who can shrug off the attacks of most weapons and heal rapidly, so most of the time it’s a desperate struggle for survival and a dash for safety. When a character is caught out at night and trying to find shelter from the monsters, the narrative puts you on the edge of your seat.

Finally, while this book has some very dark places, there is the thread of hope that Brett nurtures along the narrative: hope of turning the tide in the fight against the demons, hope of the people finding courage instead of despair, hope that characters will find their dreams, etc. My one major problem with dystopian or apocalyptic narratives is that the bleakness of them can be a real turnoff. The Warded Man shares elements of the latter genre, although it is squarely fantasy, but thankfully the bleakness does not overwhelm the narrative. Normalcy has a way of asserting itself in the midst of prolonged disaster, and Brett does a good job of showing how each character finds hope and pursues dreams and ambitions both because of and despite the nightly dangers of the demons.

Faded Wards: Where The Warded Man Could Have Been Better

While the fear people feel for the coreligns is very well established in the prose and the interpersonal interactions of characters, the demons themselves failed to dazzle or horrify). The monsters are not particularly well described in the beginning, and while I would certainly not want to be trapped outside with any of them, they didn’t scare me all that much. I kept thinking back to how Jim Butcher describes monsters, how, even when seen full view, I not only had a better idea of what they looked like and what distinguished them, but why they were frightening as well. In most monster stories, the monsters lose some pzzazz after they are revealed in full. Perhaps since Brett was revealing the mosnters very early on, they never seemed very scary. It may also be that they lost some of that oompf by being such a common sight. Still, given that they were so central to the conceit of the novel, I was a bit disappointed in their presentation.

As mentioned earlier, Brett has stated that he really admires George R. R. Martin, and that the moral complexity Martin brings to his characters has caused Brett to really bring up the level of his own writing. Like Martin, the world that Brett creates is filled with ugly, immoral people who will kill you as soon as look at you, but it’s almost too full of those characters. There are characters who help and support the viewpoint characters and characters who are unambiguously bullies or just plain evil, and I didn’t sense that there was a whole lot of a middle ground. The bullies and evil characters are frequently, and obviously, foils for the development of the viewpoint characters, but after a while the presence of a bully/rapist (or would-be rapist)/opportunist who has bad intentions on our main characters stopped being surprising and started feeling like a matter of course. Things start to feel soap-opera-ish at times. While Brett does complicate our view of one bully character greatly in the climax of this book, I sense that I will have to wait until future volumes to see how he wraps up the plot threads of these other characters, so I might just be rescinding this criticism later.

As mentioned earlier, Brett has stated that he really admires George R. R. Martin, and that the moral complexity Martin brings to his characters has caused Brett to really bring up the level of his own writing. Like Martin, the world that Brett creates is filled with ugly, immoral people who will kill you as soon as look at you, but it’s almost too full of those characters. There are characters who help and support the viewpoint characters and characters who are unambiguously bullies or just plain evil, and I didn’t sense that there was a whole lot of a middle ground. The bullies and evil characters are frequently, and obviously, foils for the development of the viewpoint characters, but after a while the presence of a bully/rapist (or would-be rapist)/opportunist who has bad intentions on our main characters stopped being surprising and started feeling like a matter of course. Things start to feel soap-opera-ish at times. While Brett does complicate our view of one bully character greatly in the climax of this book, I sense that I will have to wait until future volumes to see how he wraps up the plot threads of these other characters, so I might just be rescinding this criticism later.

My last criticism comes with a big damn hedging comment attached to it. I found myself wondering about other aspects of the world Brett had built since the worldbuilding only went so far. I imagine if demons started to rise every night in our world, they would take up a lot of our time and consideration, but normalcy and culture find ways of establishing and reestablishing themselves, so I was wondering about other aspects of the world that were not touched on. Of course, this lack of deep worldbuilding can be attributed to the fact that trade and communication is extremely limited by the nightly monster mash, so what would Rojer, Leesha, or Arlen know about far-flung lands? Still, I wanted to see the local culture, government, politics, etc. fleshed out in some more detail.

Concluding Thoughts

Despite some of these criticisms (which I may reverse my opinion on after reading the rest of the series), I enjoyed The Warded Man immensely. I was initially taken in by the central conceit of people barely surviving a nightly onslaught of demons and of kindling the hope to find a way to beat them back, but I stuck with the book for its characters and storytelling. Indeed, I’m pretty invested in Arlen, Leesha, and Rojer, and I really want to see what happens to them next and what happens to the world given the plot events set in motion by the epilogue! As I’ve stated in previous posts, I’m very discerning with what kind of fantasy I read. Perhaps I’m more of a fantasy snob than I am a Science Fiction snob, I don’t know, but I take greater care in picking my fantasy books. I was skeptical about this book, but I found myself hungry for a little fantasy and, given that Scott Lynch’s much-anticipated The Republic of Thieves kept suffering setbacks and that I’m still waiting for Martin’s A Dance with Dragons to come down to a reasonable price ($15 for the ebook from the kindle store? No thank you!) I took a chance on The Warded Man. It not only met and exceeded my standards, but it has put me in the mood to expand my fantasy horizons. I’ve already downloaded the sequel, The Desert Spear, but in between this review and the one for that book I am going to try the first parts of at least two other fantasy series.

In short, I recommend this book enthusiastically and am going to make Brett someone to keep my eye on in the future.

I listened to to this as an unabridged audiobook narrated by Pete Bradbury, whom I was dubious about at first. His somewhat deep voice has a kind of twang (one I can’t quite place) to it that at first didn’t seem to mesh with a fantasy story, but once I got used to it I enjoyed immensely. Come to find out that he has done a few roles on Law and Order and Criminal Intent, which makes me kick myself for not recognizing the book (being the L&O nut that I am).

GMRC Review: Virtual Unrealities by Alfred Bester

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed.

Alfred Bester is one writer who kind of did it all during his lifetime: science fiction, mainstream magazines, comics, television, stage, film etc., etc. In the SF community he is best known for his two novels The Demolished Man (which won the first Hugo award in 1953) and the equally dazzling The Stars My Destination (1956), both of which are amazing works that should be a part of everyone’s SF reading list. Amazing though they are, they certainly show their age. Bester did his best work in SF during the 1950s, while short fiction was still the lifeblood of the form, authors were paid by the word, and now-tired cliches were pursued with unabashed glee. The 1950s produced some great SF, to be sure, but it also produced drek that is perhaps best consumed as the target of lampooning in an episode of MST3K. Virtual Unrealities is a collection of Bester’s short work, which runs the gamut between amazingly engaging and…uh… not. Bester’s tendency to run between genius and drek is clearly outlined in Robert Silverberg’s essential introduction to the work, in which he includes a very telling quote from Damon Knight:

Alfred Bester is one writer who kind of did it all during his lifetime: science fiction, mainstream magazines, comics, television, stage, film etc., etc. In the SF community he is best known for his two novels The Demolished Man (which won the first Hugo award in 1953) and the equally dazzling The Stars My Destination (1956), both of which are amazing works that should be a part of everyone’s SF reading list. Amazing though they are, they certainly show their age. Bester did his best work in SF during the 1950s, while short fiction was still the lifeblood of the form, authors were paid by the word, and now-tired cliches were pursued with unabashed glee. The 1950s produced some great SF, to be sure, but it also produced drek that is perhaps best consumed as the target of lampooning in an episode of MST3K. Virtual Unrealities is a collection of Bester’s short work, which runs the gamut between amazingly engaging and…uh… not. Bester’s tendency to run between genius and drek is clearly outlined in Robert Silverberg’s essential introduction to the work, in which he includes a very telling quote from Damon Knight:

Dazzlement and enchantment are Bester’s methods. His stories never stand still a moment; they’re forever tilting into motion, veering, doubling back, firing off rockets to distract you…Bester’s science is all wrong, his characters are not characters but funny hats; but you never notice: he fires off a smoke bomb, climbs a ladder, leaps from a trapeze, plays three bars of “god Save the King,” swallows a sword and dives into three inches of water. Good heavens, what more do you want?

Knight hits the nail on the head here, and I really identified with his critique of Bester’s characters as merely funny hats. Most of his characters are placeholders, archetypes, and cardboard cutouts about as interesting as the paper they are printed on: they’re fairly flat, tend toward extremes, and demonstrate disturbing lack of incredulity given their situations. Take “Star Light, Star Bright” for example: when a man tells you he’s hunting for a family of missing geniuses who can defy the laws of physics and he is going to let you in on the money he can make exploiting them, you should at least make an honest effort at being skeptical before negotiating your share. Still, he can be lauded for the fact that his stories never stand still, and he plays the showman enough that, if you can run with him far enough to get where he wants you to go, there are some neat surprises in store (most of the time).

The Good, The Bad, The Psychotic, and the Overly-Credulous

Bester’s short fiction isn’t about hard science, rather it speculates about wild ideas taken to their extremes with some science thrown in (you know, for credibility’s sake). Given the loosey-goosey nature of the science, some of the stories almost read as contemporary fantasy, but I think of them closer as fantasies: extreme tales about desire, disappointment, frustration, anger, resentment, and high energy. I can imagine Bester as a showman in a flashy suit with a light-up tie clapping his hands together with a sharp, resounding crash as he leans in to a rapt audience and says “Ok, let’s see what you think of THIS one” before starting in frenetically with barely a breath between lines.

Of course, this frenetic energy meant that many of these stories are exhausting, and I found myself skipping around the book quite a bit as one story or another tried my endurance a mite too far. Each time I found myself skipping over the rest of a story because it drained me of energy (or interest), however, I would become instantly committed to another by the energy in its opening lines alone. For instance, I became utterly bored with the first story in the collection only to turn to the next (“Oddy and Id”) and be immediately sucked in by the first line: “This is the story of a monster.” When I became bogged down in the story “5,271,009,” I skipped ahead a bit and became immediately sucked in with the opener of his psychoanalytic gem “Fondly Fahrenheit”: “He doesn’t know which of us I am these days, but they know one truth. You must own nothing but yourself. You must make your own life, live your own life, and die your own death…or else you will die another’s.” This is really a testament to Bester’s ability to start a story at breakneck speed and use the resulting vortex to suck you into it.

While most of the stories in this collection begin with energy and intrigue you can feel on down to your toes, the endings vary in depth and overall effect. You can tell he’s trying to shoot the moon every time and end with pizazz. Bester’s not after a meditative hmmmm from his readers as he is a thunderous, involuntary AHA! or a long, ominous Oooohhh! Poe’s notion of “unity of effect” is applicable here. For Poe, all elements of a work of fiction should be unified in supporting the emotion or reaction that the author wants to elicit from the reader. Bester’s short work seems to exemplify unity of effect as all elements of these stories move towards a unified emotion or singular revelation in the climax. That there is really no denouement to speak of in Bester’s stories, which further indicates that the climactic AHA! moment is the point of the story. Sometimes this works out great, as in “Oddy and Id” where several scientists figure out that a young student of theirs has the power to make his unconscious desires come true. They struggle with whether or not to make the young man, Oddy, explicitly aware of this gift since until that point, while he was unaware of this gift, his actions have all been good. The climax of this story is one that stays with you for a while and works on your brain in intriguing ways, and it one of the best examples of Bester’s ability to dazzle in a conclusion.

In other works, however, the impact of that climactic moment or emotion is more akin to a fizzle than a bang. “Of Time and Third Avenue,” for example, is a predictable and ho-hum affair where a man from the future attempts to convince a man from the past to relinquish an almanac that would tell him what the future holds. The story is built around a revelation that, to my 21st century eyes at least, isn’t all that exciting and seems like it would have been overdone even at the time of its publication. That the man from the past demonstrated only the most token bit of incredulity regarding the possibility of time travel and an almanac from the future is typical Bester. He doesn’t have the time to thoroughly develop characters beyond “funny hats” or archetypes, so stories like this mean that you need to hold on to your suspension of disbelief with both hands as you read. “Star Light, Star Bright” was another fizzle for me. It slowly pulled me into an intriguing mystery involving a missing family of geniuses, but in the end it just didn’t have the payoff to make it worth the effort. The entire story felt retroactively deflated the moment I read its climax; one of those “awww, come on!” moments that make you feel silly for being invested in the plot in the first place. Bester is the consummate showman, and all of the stories in this collection are geared towards that big finish, although sometimes it fails to dazzle.

Where Bester seems to be in top form, and where his characterization is most compelling, is when writing about monsters: bad men who either make the choice to be bad or are helplessly compelled to do bad things. The protagonists of both The Demolished Man and The Stars My Destination are both wicked men (kill-your-family wicked, not fun-to-drink-with wicked), which is part of what makes them so appealing and so surprising for SF in the postwar era of the 1950s. Bester’s affinity for writing compelling monsters comes out in several stories in this collection. In “Fondly Fahrenheit” for example, a man who has never done a lick of work in his life finds himself relying on his family’s advanced, super-expensive android, and when that android ends up killing people his solution is to run away with it, as it is his only asset in the world, instead of reporting the incident and taking responsibility. “Pi Man” features a character who murders someone he likes and beats his own dog to death for no reason he can adequately explain to us or others (he’s at the whims of the cosmos), but by the end of the story even this monster is rendered sympathetic. Sometimes the compulsion or choice to do bad or evil things is funny (in the absurdist tradition), as in “The Man Who Murdered Mohammed” where a mad scientist finds his wife cheating on him and, instead of confronting her, he decides to build a time machine to go back in time and kill his wife’s mother (thereby wiping said wife out of existence) with…unexpected results. Sometimes it’s truly frightening, as in “Oddy and Id,” where we must conclude that the monster in the protagonist Oddy is no worse than the monster lurking in our own unconscious.

Where Bester seems to be in top form, and where his characterization is most compelling, is when writing about monsters: bad men who either make the choice to be bad or are helplessly compelled to do bad things. The protagonists of both The Demolished Man and The Stars My Destination are both wicked men (kill-your-family wicked, not fun-to-drink-with wicked), which is part of what makes them so appealing and so surprising for SF in the postwar era of the 1950s. Bester’s affinity for writing compelling monsters comes out in several stories in this collection. In “Fondly Fahrenheit” for example, a man who has never done a lick of work in his life finds himself relying on his family’s advanced, super-expensive android, and when that android ends up killing people his solution is to run away with it, as it is his only asset in the world, instead of reporting the incident and taking responsibility. “Pi Man” features a character who murders someone he likes and beats his own dog to death for no reason he can adequately explain to us or others (he’s at the whims of the cosmos), but by the end of the story even this monster is rendered sympathetic. Sometimes the compulsion or choice to do bad or evil things is funny (in the absurdist tradition), as in “The Man Who Murdered Mohammed” where a mad scientist finds his wife cheating on him and, instead of confronting her, he decides to build a time machine to go back in time and kill his wife’s mother (thereby wiping said wife out of existence) with…unexpected results. Sometimes it’s truly frightening, as in “Oddy and Id,” where we must conclude that the monster in the protagonist Oddy is no worse than the monster lurking in our own unconscious.

“Oddy and Id” is a good example of Bester’s fascination with psychology, particularly Freudian psychoanalysis, which played a pervasive role in his Hugo-award winning The Demolished Man. We could do strong Freduian readings of most stories in this collection, particularly “Time is the Traitor” which involves an investigation into the trauma of The Decider (no, not George Bush) who despite an almost prescient ability to predict the future (affecting the lives of billions and making him the richest, most powerful man ever) has the inexplicable compulsion to kill any and every man named Kruger that he comes across. While psychology has moved beyond Freud in many/most ways–which certainly doesn’t help the already-precarious way in which Bester’s work has aged–it nevertheless is appealing since it allows Bester to tap into and play with the unpredictable forces of the mind and make seemingly malevolent characters seem sympathetic and understandable to a degree. These characters visibly struggle with their desires, and those stories are where Bester’s characters are the closest to being actual characters instead of funny hats (funny like an over-the-top Derby hat).

I would also draw attention to another endearing bit of Bester’s experimentation: how he plays with the way words sit on the page. Occasionally he will often draw pictures using words that require you to read the page in a different way, to re-orient yourself to the story, or just to thumb you in the eye and defy your expectations. This was a pretty avant garde move for Bester in the 50′s and 60′s, predating the most experimental Language Poets (who also played with typeset and the form of words on the page) by at least a decade or two.

The Best of Bester?

In some ways, Bester was very much ahead of his time, and in others he was of it, which is one reason his fiction has dated pretty hard. If you know how to approach his work, however, you can look past its datedness (to a degree) and see the unbridled play going on underneath. It’s not without its problems, however. Virtual Unrealities is a collection that shows both sides of Bester: the frenetic genius and the trite, cliched stuff. Some of his stories are fun, others are haunting, and yet others have all the luster of a poorly-planned and poorly-timed joke. Silverberg, however, rightly notes in his forward that all of them–the good and the bad–are crackling with the energy, enthusiasm, and showmanship that was Bester’s hallmark. If you read this collection for the razzle and the dazzle, knowing in advance that it has aged hard and that he is shooting not for meditation but a unity of effect that privileges that AHA! moment at the end, then you too can have some fun with Virtual Unrealities, as I did.

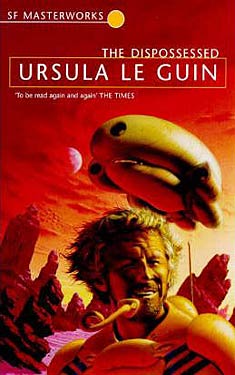

GMRC Review: The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and has chimed in with his first GMRC review of one of the all time classics of SF.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and has chimed in with his first GMRC review of one of the all time classics of SF.

The Dispossessed is the fourth book in Ursula K. Le Guin‘s Hainish Cycle, which is a loosely connected series of books, novellas, and short stories utilizing the background of an inter-stellar proto-humanity that seeks to reunite it’s disparate colonies. Although it is the fifth work in the series, chronologically it is the first. Le Guin pulled at hat trick with this one and nabbed the 1974 Nebula and the 1975 Hugo and Locus awards. My only other experience with Le Guin was reading The Left Hand of Darkness (another book in the Hainish cycle) as part of a capstone fiction class for my Bachelor’s degree. We really dug into the book, and one element we looked at particularly closely is the cyclical plot structure in which the protagonist, Genly Ai, ends up where he started, though greatly changed by the experience. Thinking about that reading experience reminded me of what a visiting author said in a lecture that same year: there are two types of stories, someone goes on a trip or a stranger comes to town. Sometimes, though, that stranger is you returning. Indeed, illustrating that appears to be the point of The Dispossessed‘s structure and themes: to take us on a trip to a world similar to ours, but through different eyes so that the familiar becomes strange and we, upon returning from the journey, are changed by the experience. Le Guin has characterized herself and has been characterized as an anthropologist of cultures that never existed, but might in the future, and The Disposessed is a prime example that puts paid to this claim. The science in this book is very soft, but like The Left Hand of Darkness, it delves deep into social structures and hierarchies that characters within her fictional societies have built and struggle within.

The Dispossessed is the fourth book in Ursula K. Le Guin‘s Hainish Cycle, which is a loosely connected series of books, novellas, and short stories utilizing the background of an inter-stellar proto-humanity that seeks to reunite it’s disparate colonies. Although it is the fifth work in the series, chronologically it is the first. Le Guin pulled at hat trick with this one and nabbed the 1974 Nebula and the 1975 Hugo and Locus awards. My only other experience with Le Guin was reading The Left Hand of Darkness (another book in the Hainish cycle) as part of a capstone fiction class for my Bachelor’s degree. We really dug into the book, and one element we looked at particularly closely is the cyclical plot structure in which the protagonist, Genly Ai, ends up where he started, though greatly changed by the experience. Thinking about that reading experience reminded me of what a visiting author said in a lecture that same year: there are two types of stories, someone goes on a trip or a stranger comes to town. Sometimes, though, that stranger is you returning. Indeed, illustrating that appears to be the point of The Dispossessed‘s structure and themes: to take us on a trip to a world similar to ours, but through different eyes so that the familiar becomes strange and we, upon returning from the journey, are changed by the experience. Le Guin has characterized herself and has been characterized as an anthropologist of cultures that never existed, but might in the future, and The Disposessed is a prime example that puts paid to this claim. The science in this book is very soft, but like The Left Hand of Darkness, it delves deep into social structures and hierarchies that characters within her fictional societies have built and struggle within.

The Dispossessed takes place on the planets of Urres and Anarres, which orbit one another in the Tau Ceti star system. Anarres is a desert planet colonized by anarchists who split with Urres. The Anarresti anarchy eschews money, property, and materialism in general, favoring an extremely decentralized government in which an individual is free to do what he/she wants, but is always expected to contribute to the communal whole. Annarresti’s share in both the drudge work like planting crops and waste management as well as the higher-order tasks such as management and even research. Everyone pitches in, and being selfish or "egoizing" is frowned upon. This makes Shevek, our protagonist, somewhat of an outlier. Shevek struggles with being a member of the community and with trying to fulfill his dream of creating a unified theory of space and time. It is his ideas that will make the interstellar communicator, the ansible (an important device in the other parts of the Hainish cycle) possible. But the work isolates him, since few understand it or even want to. He eventually seeks intellectual community with the scientists on Urres, which the Anarrans regard as wicked, materialistic heathens. Shevek risks becoming anathema to his people not only because his theory could reveal the way to bring the communities of star-flung humanity together, but also a way to lower the barriers separating Urres and Anarres. Of course, everyone on Urres wants to be the ones to get their hands on Shevek’s work, and he slowly comes to realize the peril this puts him in. Through Shevek’s anarchist eyes, we see how the people of Urres–particularly the caplitalist, materialist A-Io and the communist nation of Thu (mirroring the United States and Soviet Russia respectively)–are strange and sometimes horrifying, but not irredemable.

What The Dispossessed Does Well

The science in this book is very soft. Indeed, it is pretty much downplayed throughout. Even Shevek’s theories of space-time are not expounded upon beyond some simple analogies. This is pure social science fiction, and it is perhaps best approached with an anthropologist’s eye for social dynamics. Shevek comes from a world where one is brought up from childhood to see everyone as a brother or sister (even one’s biological parents), to treat everyone equally, and to eschew the idea of personal property, and to contribute to one’s society. One of the strengths of this book is in Le Guin’s speculation on how a utopian society of anarchists might function to achieve these goals (anarchy here does not connote an absence of morality or order, but rather a society without institutionalized hierarchies of power and control). Crime is negated by eradicating money and making all property communal and free, therefore there is no need to steal or murder someone for what he/she has. People work as they want to, and given the strong social nature of this society, most people pitch in in some way to contribute. This leads to a large portion of unspecialized labor, but it encourages people to work for what pleases them and what motivates them instead of being chained to the same job. Le Guin incorporates a somewhat strong version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis as a tool for reinforcing the anarchic ideals of Anarres. You do not refer to something as "my book" on Annares, but say "the book". You don’t ask, "can I see your book," you say, "can I use the book that you are using"? It gets weird some times when characters say "the mother" instead of "your mother," or "the nose hurts" instead of "my nose hurts," but it’s all geared towards eliminating possessiveness: if the use of language affects cognition and non-linguistic actions, then eliminating possessiveness in speech eliminates it in thought and action, according to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

The plot structure also mirrors this duality: the chapters alternate between Shevek’s time on Urres and his earlier life on Anarres, with situations and themes from these alternating chapters mirroring each other. Just as the two planets orbit one another, Le Guin creates a constant juxtaposition of the two worlds throughout the book. We will see the material excesses, the squalor of the poor, and the "savage civility" (a term I loved from John Masters’ description of the upperclasses in Nightrunners of Bengal) of the Urresti capitalists in one chapter, and how the solidarity of the Anarrans was strenghtened by the way they pull together during a food shortage in the next. Since the social-political situation on Urres is close to that of the Cold-War era Untied States and Soviet Union, Shevek provides a contrasting viewpoint that let’s Le Guin level some pretty incisive criticism about the inequality of men and women, material excess, the petty (and dangerous) nationalism, the governmental and corporate co-opting of science, etc.

The contrast between the two worlds and the way these differences are presented in the alternating plot structure makes Anarres seem a tempting utopia, but thankfully Le Guin complicates the issue. The book is subtitled "An Ambiguous Utopia," after all, and Anarres is not perfect. In the generations following the revolution, informal power hierarchies establish themselves, sometimes explicitly–as in the case of the inept yet famous scientist Sabul whom Shevek has to appease to get his theories published–and tacitly, as in peer pressure. This ambiguity is further reinforced by the beauty on Urres, such as the technological wonders of aircraft and spaceships and the general material abundance, which is made possible by the plentiful resources of the planet. Shevek wrestles with these differeneces and moves towards a realization of how he can help revitalize the revolution on his planet, and thus he ends where he began and completes the loop mirrored in his theory of simultaneity and the oft quoted dictum by Anarres’ intellectual founder that "true journey is return." All of this is presented pretty well through conversations (the tenor of which makes me think of Kim Stanley Robinson sans the hard science) and through Shevek’s observations, tinged by his upbringing in a very different society than that of Urres, which leads to scenes that are sometimes hilarious, sometimes disquieting, but always thought provoking. The complications Le Guin adds to the Annaresti anarchy and the startling beauty Shevek occasionally notices on Urres keeps the plot of the themes from being cliche or simplistic.

The contrast between the two worlds and the way these differences are presented in the alternating plot structure makes Anarres seem a tempting utopia, but thankfully Le Guin complicates the issue. The book is subtitled "An Ambiguous Utopia," after all, and Anarres is not perfect. In the generations following the revolution, informal power hierarchies establish themselves, sometimes explicitly–as in the case of the inept yet famous scientist Sabul whom Shevek has to appease to get his theories published–and tacitly, as in peer pressure. This ambiguity is further reinforced by the beauty on Urres, such as the technological wonders of aircraft and spaceships and the general material abundance, which is made possible by the plentiful resources of the planet. Shevek wrestles with these differeneces and moves towards a realization of how he can help revitalize the revolution on his planet, and thus he ends where he began and completes the loop mirrored in his theory of simultaneity and the oft quoted dictum by Anarres’ intellectual founder that "true journey is return." All of this is presented pretty well through conversations (the tenor of which makes me think of Kim Stanley Robinson sans the hard science) and through Shevek’s observations, tinged by his upbringing in a very different society than that of Urres, which leads to scenes that are sometimes hilarious, sometimes disquieting, but always thought provoking. The complications Le Guin adds to the Annaresti anarchy and the startling beauty Shevek occasionally notices on Urres keeps the plot of the themes from being cliche or simplistic.

Where The Disposessed Could Have Been Better

Even though this is a work of social science fiction, sometimes the narrative can feel disembodied as it summarizes situations or stretches of time in Shevek’s life. These scenes do reveal a great deal about Annaresti society, but such exposition can distract from Shevek’s narrative. When Le Guin does delve into an extended scene there is some great characterization done in the dialog, but the lengthy exposition lies between these scenes and bobbing in and out of it left me feeling light headed at times. The alternating chapters also made me feel dizzy as the narrative shifted gears, and for some reason I was frequently drawn in to the scene at the end of a chapter only to be extremely disoriented when the narrative shifted to the other planet and the other time period. Perhaps this disorientation is intended, but it still bothered me during those transitions. This is also a book that is curiously without much visual or technological sensawunda. My memories of The Left Hand of Darkness are punctuated by that pervasive awareness of how cold the planet of Gethen was, and of the strangeness of the neuter people there. More visual or technological play in the book would have added welcome nice spice to the narrative.

Concluding Thoughts

The Disposessed is a great book if you know how to approach it. It is social science fiction, so there is not much in the way of action. It is best to approach this book with an anthropologist’s eye, paying attention more to the speculation on social dynamics than to the technological advancements. Still, it’s very thoughtful and incisive, and it illustrates an important facet of SF that readers outside of the genre probably don’t think it can do very well: deep social critique. Although it was written thirty seven years ago, it still feels fresh and interesting. It’s an important piece of SF, and a nice companion to The Left Hand of Darkness.

Score: 5/5

Full Details

Full Details