Be My Enemy by Ian McDonald

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Scott’s Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, in an attempt to understand the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

No Letdown in the Everness Series

No Letdown in the Everness Series

The adventures of teenage genius Everett Singh and his Earth 3 “electropunk” airship crew companions continue in Ian McDonald‘s second installment of the young adult Everness series, Be My Enemy (2012). I enjoyed this one even more than the first (Planesrunner), as McDonald uses an adventure romp through the multiverse to bring out one science fictional concept after another, while still managing to further explore his characters and their relationships, especially that between Everett and Sen, the adopted daughter of Everness‘s captain and Everett’s partner in adventure. The search for Everett’s father continues, as does the pursuit of Everett by the villainous Order responsible for his father’s disappearance.

(Insert Planesrunner spoiler alert here!) At the end of the previous novel, Everett had used his Infundibulum technology, which allows travel anywhere in the multiverse, to escape evil villainess Charlotte Villers and her colleagues from the Order—the still shady group determined to maintain control over travel within the multiverse, and thus willing to do whatever is necessary to get their hands on Everett’s Infundibulum—to escape to an unexplored alternate Earth currently in the grip of an ice age. But Charlotte, now with her “alternate” from another Earth, Charles Villiers, in tow, is able to track them, leading them to jump once again, this time back to Everett’s (and our) Earth.

Forays into Fantasy: Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, in an attempt to understand the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Gormenghast was released in 1950, the same year as The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Lord of the Rings would soon follow. These latter two works may be seen as the defining fantasies of the second half of the twentieth century, altering the landscape of the field, popularizing the secondary world fantasy and setting the stage for the advent of fantasy as a commercial genre in the late 1960s. As well as developing an enduring popularity that continues into the present, these books (especially, or course, The Lord of the Rings) have been more influential on fantasy literature than anything since. And yet, though it is not read as widely as these two contemporaries, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, conceived in that same post-war period in England, seem to me to be just as important. Unlike Tolkien and Lewis, Peake has not inspired hordes of imitators or greatly influenced the direction of commercial fantasy. The influence of Mervyn Peake could not be based on imitating the plot structure or external trappings of his creation—the books are too idiosyncratic for that to be a temptation. Rather, the strand of Peake’s influence can be seen in those writers of modern fantasy who have rejected the commercial allure of Tolkien-like epic fantasy in order to pursue their own personal fantastic visions, and those for whom character, theme, and style are at least as important as plot and exterior world-building.

Gormenghast was released in 1950, the same year as The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Lord of the Rings would soon follow. These latter two works may be seen as the defining fantasies of the second half of the twentieth century, altering the landscape of the field, popularizing the secondary world fantasy and setting the stage for the advent of fantasy as a commercial genre in the late 1960s. As well as developing an enduring popularity that continues into the present, these books (especially, or course, The Lord of the Rings) have been more influential on fantasy literature than anything since. And yet, though it is not read as widely as these two contemporaries, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, conceived in that same post-war period in England, seem to me to be just as important. Unlike Tolkien and Lewis, Peake has not inspired hordes of imitators or greatly influenced the direction of commercial fantasy. The influence of Mervyn Peake could not be based on imitating the plot structure or external trappings of his creation—the books are too idiosyncratic for that to be a temptation. Rather, the strand of Peake’s influence can be seen in those writers of modern fantasy who have rejected the commercial allure of Tolkien-like epic fantasy in order to pursue their own personal fantastic visions, and those for whom character, theme, and style are at least as important as plot and exterior world-building.

This is not to say that world-building is not important in Peake’s works, but it is not of the sort that epic fantasy fans will be looking for. The inhabitants of Gormenghast can only be defined in relation to the environment their forebears created for them, and this environment—Gormenghast castle and it’s immediate natural surroundings—is described in such visual terms that the setting is evoked in a way rarely achieved, and this setting is arguably more interesting than any individual character. But this world-building is focused interiorly on the isolated castle. There’s no need for a map to track the characters’ progress, and the outside world is never described in the first two Gormenghast novels. This aspect adds to the strangeness and dislocation created by Peake’s writing, since the reader knows nothing of the larger world in which Gormenghast is situated. The result is a strange combination of dislocation and concreteness. We do not know where or when Gormenghast exists, yet it comes to seem entirely real on its own terms. The concreteness of the castle setting is further enhanced by the fact that Gormenghast seemingly has not changed for centuries, possibly millennia (aside from a slow deterioration), and it is this fact that creates the conflict that first become apparent in the first Gormenghast novel, Titus Groan (1946, see previous post), and comes to a head in the second, Gormenghast (1950).

Forays into Fantasy: William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, in an attempt to understand the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

In an earlier Foray into Fantasy, I looked at William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland (1908) as an influential early precursor of the weird tale, a difficult-to-define subgenre of fantasy portraying incursions of the inexplicable or uncanny into our consensual reality. Since then, I’ve been looking forward to reading The Night Land (1912), Hodgson’s fourth and final novel, which, though sometimes cited as his masterpiece, is not as often read today due to its length and distracting pseudo-archaic English. While it certainly has touches of the weird, The Night Land is also an amalgamation of fantasy, science fiction, horror, and romance, its uniqueness compounded by its extremely unusual narrative viewpoint.

In an earlier Foray into Fantasy, I looked at William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland (1908) as an influential early precursor of the weird tale, a difficult-to-define subgenre of fantasy portraying incursions of the inexplicable or uncanny into our consensual reality. Since then, I’ve been looking forward to reading The Night Land (1912), Hodgson’s fourth and final novel, which, though sometimes cited as his masterpiece, is not as often read today due to its length and distracting pseudo-archaic English. While it certainly has touches of the weird, The Night Land is also an amalgamation of fantasy, science fiction, horror, and romance, its uniqueness compounded by its extremely unusual narrative viewpoint.

The first chapter tells of the courtship and marriage of Mirdath and the unnamed narrator. Based on the writing style and details of the setting, it seems to take place in England in the seventeenth century, though this is not specified. When Mirdath dies in childbirth, the narrator, who idealized his wife with an intense degree of sentimentality, is plunged into despair. Somehow, whether through some form of clairvoyant reincarnation or psychic time travel (the ambiguous possibility of both mystical and science fictional interpretations is characteristic of the novel), he finds himself occupying the mind of a young man living on the dying earth millions of years in the future, after the sun has stopped emitting visible light, and humanity has retreated into the “Great Redoubt”—a giant metal pyramid powered by the “Earth Current” and protected from the malevolent forces of the Night Land by a sort of force field. The remainder of the novel is narrated from the perspective of this seventeenth century Englishman, now with the knowledge of the young man of the future whose mind he co-occupies, describing this future dying earth and his quest to regain his lost love—a journey through a blighted landscape teeming with evil creatures.

WoGF Review: Zoo City by Lauren Beukes

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted many fine reviews for WWEnd including several for last year’s GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted many fine reviews for WWEnd including several for last year’s GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Stories often succeed by doing one or two things especially well. A novel may stick with us because of a memorable character, a fascinating setting, or due to unique or interesting ideas. Zoo City is especially successful in that none of these elements are neglected, and all are brought together by Lauren Beukes in a satisfying whole within a novel that is relatively short and self-contained. Looking back after finishing it, the craft that must have gone into creating the work becomes more apparent. I’ll focus on four of the novel’s strengths, each of which, by itself, would probably be enough to maintain interest in the book. The fact that they are successfully brought together makes Zoo City a compulsive read…

Stories often succeed by doing one or two things especially well. A novel may stick with us because of a memorable character, a fascinating setting, or due to unique or interesting ideas. Zoo City is especially successful in that none of these elements are neglected, and all are brought together by Lauren Beukes in a satisfying whole within a novel that is relatively short and self-contained. Looking back after finishing it, the craft that must have gone into creating the work becomes more apparent. I’ll focus on four of the novel’s strengths, each of which, by itself, would probably be enough to maintain interest in the book. The fact that they are successfully brought together makes Zoo City a compulsive read…

First, the story is told in the first person by Zinzi December, a character whose intelligence and resourcefulness, as well as her guilt, doubt, and regret, are both revealed and explained compellingly. She becomes a character that we want to learn more about. She has fallen on hard times, scraping a living by using her talent for finding lost things (more on that in the next paragraph), as well as using her “Former Life” talent as a writer to come up with scam emails in order to repay drug-related debts owed to a criminal organization. Along the way, we learn how she went from up-and-coming journalist from an educated middle-class background to scraping by as she can day to day in the Zoo City ghetto of Johannesburg. As we get to know the character, we are drawn into her struggle to come to terms with her past, and to find a route back into the journalistic world, while struggling to “do the right thing” and make up for past and current mistakes.

Forays into Fantasy: Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

With its ability to portray worlds and societies unconstrained by the realities of our experience, speculative fiction has always been a venue for criticizing or championing political systems, real and imagined. At the turn of the twentieth century, at the same time that commercial fantasy was moving in the direction of Burroughsian adventure, sword and sorcery and the weird tale, fantasy was also still being written by authors outside the pulp ghetto that was just beginning to establish itself. During this same period, the triumph of large-scale industrial capitalism in the United States was resulting in a political counter-reaction in the form of populist and socialist movements looking to alter or replace this system, as well as social reform movements working to ameliorate the growing problem of urban poverty that accompanied the creation of previously unheard-of concentrations of wealth by the “robber barons” of the Gilded Age. Socialists such as Jack London, with his anti-capitalist dystopia The Iron Heel (1908), and Edward Bellamy, with his best-selling socialist utopia Looking Backward, 2000–1887 (1889), used fantastic fiction to criticize American economic conditions, and attempted to inspire alternative social movements. Such books were widely read by an audience that would have been mostly uninterested in the pulp fantasy starting to appear around the same time, and are representative of the end of an era in which fantastika was one of many fictional modes used by authors as diverse and widely respected as Mark Twain, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry James.

With its ability to portray worlds and societies unconstrained by the realities of our experience, speculative fiction has always been a venue for criticizing or championing political systems, real and imagined. At the turn of the twentieth century, at the same time that commercial fantasy was moving in the direction of Burroughsian adventure, sword and sorcery and the weird tale, fantasy was also still being written by authors outside the pulp ghetto that was just beginning to establish itself. During this same period, the triumph of large-scale industrial capitalism in the United States was resulting in a political counter-reaction in the form of populist and socialist movements looking to alter or replace this system, as well as social reform movements working to ameliorate the growing problem of urban poverty that accompanied the creation of previously unheard-of concentrations of wealth by the “robber barons” of the Gilded Age. Socialists such as Jack London, with his anti-capitalist dystopia The Iron Heel (1908), and Edward Bellamy, with his best-selling socialist utopia Looking Backward, 2000–1887 (1889), used fantastic fiction to criticize American economic conditions, and attempted to inspire alternative social movements. Such books were widely read by an audience that would have been mostly uninterested in the pulp fantasy starting to appear around the same time, and are representative of the end of an era in which fantastika was one of many fictional modes used by authors as diverse and widely respected as Mark Twain, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry James.

New E-Books from Clarke, Wolfe, and Foster

In discussions of the pros and cons of e-books, supporters of the growing shift toward electronic readers cite the convenience of e-readers and tablets, the ability to instantly download a new book when browsing an online store, and the cost-free virtual (and virtually unlimited) shelf space. Personally, the ability to accumulate more books without reaching the point of needing to add another room to the house in order to store them is a fantastic development.

In discussions of the pros and cons of e-books, supporters of the growing shift toward electronic readers cite the convenience of e-readers and tablets, the ability to instantly download a new book when browsing an online store, and the cost-free virtual (and virtually unlimited) shelf space. Personally, the ability to accumulate more books without reaching the point of needing to add another room to the house in order to store them is a fantastic development.

But, to my mind, by far the largest boon of the e-book revolution is the way it has made available previously out-of-print backlists of a large number of authors that would have been unlikely to make it back into print as physical books, due to the economics of books publishing, and publishers’ increasing unwillingness to keep marginally profitable “midlist” writers works’ in print. Major publishers have slowly gotten into the act with digital reprints of the books they have rights to, but there also an increasing number of authors (or authors’ estates), the rights to whose backlists have reverted to them, who have taken the opportunity to arrange for digital reissues. Back catalogues that have appeared for the first time or been added to in the last few months include:

GMRC Review: Always Coming Home by Ursula K. Le Guin

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted man fine reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted man fine reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

To borrow from the title of one of the first sections of Always Coming Home, this book is an “archaeology of the future.” I purposely use the term book rather than novel, since the structure of Ursula K. Le Guin‘s 1985 work makes it more of a collage than a narrative, though it does tell a story, and it certainly has a theme. The story is that of an entire people—the Kesh, the People of the Valley, living in the far distant future somewhere in Northern California. A changed climate has created an inland sea east of the Valley, and the people who live there are still dealing with the legacy of the chemical wastes left behind by a long-gone civilization whom the Kesh think of as people “who lived outside the world” and whose poisonous lifestyle has led to their being remembered in legends and visions as people who (literally) had their heads on backwards.

To borrow from the title of one of the first sections of Always Coming Home, this book is an “archaeology of the future.” I purposely use the term book rather than novel, since the structure of Ursula K. Le Guin‘s 1985 work makes it more of a collage than a narrative, though it does tell a story, and it certainly has a theme. The story is that of an entire people—the Kesh, the People of the Valley, living in the far distant future somewhere in Northern California. A changed climate has created an inland sea east of the Valley, and the people who live there are still dealing with the legacy of the chemical wastes left behind by a long-gone civilization whom the Kesh think of as people “who lived outside the world” and whose poisonous lifestyle has led to their being remembered in legends and visions as people who (literally) had their heads on backwards.

The Kesh civilization may be the ultimate working out of Le Guin’s utopian ideals. Her best-known science fiction novels—The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed—both posit alien societies that encourage readers to consider alternative gender roles and economic systems. Her subtitle for The Dispossessed—”An Ambiguous Utopia”—could apply just as well to Always Coming Home. The inability of the Kesh to comprehend a society like ours is due to their commitment to a post-industrial environmentally sustainable way of life (though they would never use such terminology, thinking of themselves as merely “living in the world”). That way of life—reminiscent of a settled Native American culture—is centered on a compatibility with nature. Nothing is taken that is not needed. The wealthiest are those who give the most, not those who accumulate possessions. A low human population density is scrupulously maintained. Communities are organized around both families and occupations, with each individual encouraged to pursue the work most amenable to her. Everyone works, and labor is not resented. Authority is entirely decentralized, and sexism is nonexistent. The Kesh are aware of the possibility of more advanced technologies, but choose not to pursue them, failing to see the point, and unwilling to sacrifice their environment. Their society works, and the reader understand why they would see us as “backward-heads.” As in the other two novels mentioned above, Le Guin invites the reader to question our own society by asking us to consider the possibility of a workable alternative. One of the great attractions of science fiction is its ability to encourage us to consider how things could be different, and Le Guin does this masterfully in Always Coming Home, though not in a way that science fiction readers are used to.

GMRC Review: The End of Eternity by Isaac Asimov

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

When I started reading science fiction, Heinlein, Asimov, and Clarke were the “big three” SF writers—already thought of as the authors of classics while they were still alive and writing. Of the three, Asimov was the favorite of my youth. I appreciated his rigorous logic, humanism, and devotion to the idea that human rationality and science would continue to move us forward into a challenging but ultimately triumphant future. Having not read his work for decades, I looked forward to reacquainting myself with Asimov, but with some trepidation, since it seems that the “Good Doctor” has lost some of his critical luster over the years, and it’s true that sometimes the favorites of adolescence are best left to remain as pleasant memories. David Pringle included The End of Eternity (1955) in his 100 Best, but only grudgingly: “He is one of the best-known sf writers in the world, so I felt I had to include something by Isaac Asimov, though I confess I have little enthusiasm for his work.” His essay on the novel certainly reflects that lack of enthusiasm.

Returning to the novel, the source of the difficulty with Asimov quickly became clear. Asimov, possibly more than any other author, embodies a common dichotomy in Golden Age science fiction: the focus is on ideas and plot, while characterization and prose style often do not hold up to the standards that modern genre readers expect. Asimov was open about the fact that his prose was purely functional and transparent—its job was to present the story without in itself being noticeable. For young readers, this may be especially appealing, but the success of the stories rides on the mind-blowing concepts and/or engaging plots on which Asimov’s fictions succeeds or fails. Readers looking for complex characterization or vivid descriptive writing will have to look elsewhere. But for anyone tolerant of such failings, or willing to overlook them in the interest of a good story, The End of Eternity still holds up as one of the great time travel novels, a nice blend of science fiction and mystery (a strength of Asimov’s), and a fine example of the author’s humanistic themes.

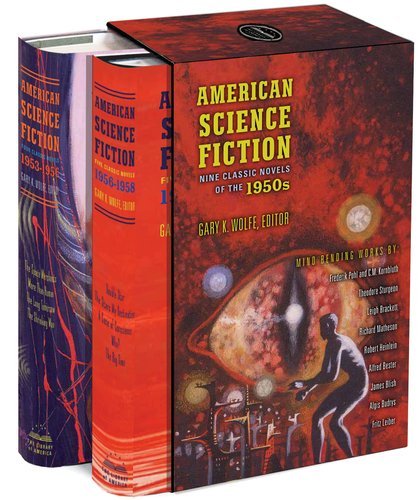

American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s from the Library of America

As the year of the Grand Master Reading Challenge at Worlds Without End winds down, some of you may, like me, be scrambling to complete it. It seems timely, then, that the Library of America has just released the two-volume American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s, which contains four Grand Master novels, along with five that probably should be (how can Theodore Sturgeon not be a Grand Master?).

Four Classic Novels 1953-1956

Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth, The Space Merchants

Theodore Sturgeon, More Than Human

Leigh Brackett, The Long Tomorrow

Richard Matheson, The Shrinking Man

Five Classic Novels 1956-58

Robert A. Heinlein, Double Star

Alfred Bester, The Stars My Destination

James Blish, A Case of Conscience

Algis Budrys, Who?

Fritz Leiber, The Big Time

More information on the books, including introductions to each by current writers such as Neil Gaiman, William Gibson, and Connie Willis, along with a timeline of 1950s SF, a gallery of cover art, contemporary radio and TV adaptations, and essays by editor Gary K. Wolfe, Robert Silverberg, and Barry Malzberg, can be found at a website created by the Library of American to accompany the set. (Consistent with the Library’s policy from its inception, the books themselves contain the novels’ texts, without introduction or commentary.)

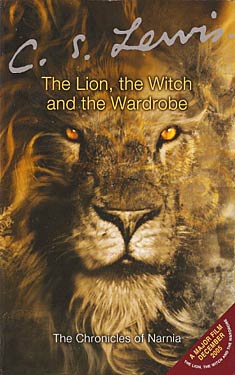

Forays into Fantasy: C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Between them, J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis have been credited with reinventing and reinvigorating fantasy literature for the second half of the twentieth century, both creatively and, ultimately, commercially. Amazingly, the two writers most influential on modern fantasy were both professors of medieval language and literature at Oxford University, as well as being good friends, during the period in which they wrote, respectively, The Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia. Both were members of an informal reading and writing group known as the Inklings, where they discussed their works in progress and their ideas about fantasy. The two were also bound by the shared experience of fighting in the trenches of World War I, and by their devotion to Christianity. In 1931, Tolkien was among those who helped convert the atheist Lewis, though Lewis did not embrace Tolkien’s Catholicism. The religious background of an author is not something that will come up often in my survey of fantasy, but in this case it is relevant to an understanding of Lewis’s work, nearly all of which is related to his religious ideas in some way.

Between them, J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis have been credited with reinventing and reinvigorating fantasy literature for the second half of the twentieth century, both creatively and, ultimately, commercially. Amazingly, the two writers most influential on modern fantasy were both professors of medieval language and literature at Oxford University, as well as being good friends, during the period in which they wrote, respectively, The Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia. Both were members of an informal reading and writing group known as the Inklings, where they discussed their works in progress and their ideas about fantasy. The two were also bound by the shared experience of fighting in the trenches of World War I, and by their devotion to Christianity. In 1931, Tolkien was among those who helped convert the atheist Lewis, though Lewis did not embrace Tolkien’s Catholicism. The religious background of an author is not something that will come up often in my survey of fantasy, but in this case it is relevant to an understanding of Lewis’s work, nearly all of which is related to his religious ideas in some way.

Given their many affinities, then, it may come as a surprise that Tolkien expressed strong dislike for The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950), and the six subsequent Narnia volumes. Yet comparing it to Tolkien’s work may explain why. Tolkien, after all, is heralded as the master of what has come to be known as world-building, spending years inventing the languages, history, and geography of Middle Earth prior to writing The Lord of the Rings. This world building is probably the most influential aspect of his work, its popularity creating a large readership that would subsequently be accustomed to accepting secondary world fantasies—stories set in imagined lands with no necessary connection to ours—as a genre in itself. Fans demanded more of it, leading to the fantasy publishing boom that began after the paperback publication of The Lord of the Rings in the late ‘60s.

Full Details

Full Details