GMRC Review: The Languages of Pao by Jack Vance

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our “South African Bureau.”) Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the sixth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our “South African Bureau.”) Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the sixth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

First, a confession. I have not before this book read any of Jack Vance‘s novels. Even so I’m well aware of the fact that he has long been regarded as a very accomplished creator of planetary romances and “dying Earth” fantasies, of which many fine reviews have been submitted for the GMRC. Most reviewers laud his genius for coining memorable and believable nouns for unearthly beings and artefacts, all the more solidying successful attempts to create memorable, spellbinding worlds impregnated with Damon Knight‘s sense of wonder. In The Languages of Pao Vance has created another clever, original adventure story, radiating with verbal and world-building skills. As this is the only Vance I’ve read, I can’t compare its magniloquence and style with other work, but can state that it certainly has enticed me to read more from his corpus.

First, a confession. I have not before this book read any of Jack Vance‘s novels. Even so I’m well aware of the fact that he has long been regarded as a very accomplished creator of planetary romances and “dying Earth” fantasies, of which many fine reviews have been submitted for the GMRC. Most reviewers laud his genius for coining memorable and believable nouns for unearthly beings and artefacts, all the more solidying successful attempts to create memorable, spellbinding worlds impregnated with Damon Knight‘s sense of wonder. In The Languages of Pao Vance has created another clever, original adventure story, radiating with verbal and world-building skills. As this is the only Vance I’ve read, I can’t compare its magniloquence and style with other work, but can state that it certainly has enticed me to read more from his corpus.

The focus of the novel is on linguistics, built around a plot structure powered by the idea of vocabulary as humankind’s means of progress, but despite the seemingly high concept nature of the story, it’s far from an academic read. It starts off with an assassination of Panarch Panasper, apparently by his son Beran. It’s all a clandestine conspiracy by Beran’s uncle Bustamonte, who becomes the Regent while Beran himself is spirited away to Breakness, a world dominated by the Wizards of the Institute, males with cunning intellects that are only matched by their cybernetic augmentations, which bestow them with superpowers. Beran’s benefactor Palofax is the most augmented man on Breakness, and under his tutelage Beran grows to manhood while studying linguistics. From the outset Bustamonte’s reign is beset with difficulties, and Pao is easily conquered by raiders from the planet Batmarsh and forced to pay substantial annual tributes. Bustamonte travels to Breakness to secure help from Palofax, who has his own designs on Pao. They agree that a new breed of Paonese is required, because until then Pao has largely been a rural population that was culturally, linguistically and politically identical. Even in their language the Paonese were conspicuously docile and dispassionate and devoid of a fighting spirit. It’s inexplicable how a planet with 15 billion souls could be so easily overcome by a mere 10,000! Palofax is intent on changing the psychological foundation of Pao, which begins with the Paonese language:

GMRC Review: Hothouse by Brian W. Aldiss

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our “South African Bureau.”) Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the fifth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our “South African Bureau.”) Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the fifth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

In the late 1960s Brian W. Aldiss became known as part of the New Wave in British science fiction, along with J. G. Ballard, whose The Drowned World shares some common themes with Hothouse. He remains a major voice in SF, and his history of the genre, Billion Year Spree, is still referred to by literary critics and fans alike. A fascinating observation is that almost all of his novels are narratives of exploration in one way or another, with the possibility of personal enlightenment open to the protagonists. Hothouse is no different.

In the late 1960s Brian W. Aldiss became known as part of the New Wave in British science fiction, along with J. G. Ballard, whose The Drowned World shares some common themes with Hothouse. He remains a major voice in SF, and his history of the genre, Billion Year Spree, is still referred to by literary critics and fans alike. A fascinating observation is that almost all of his novels are narratives of exploration in one way or another, with the possibility of personal enlightenment open to the protagonists. Hothouse is no different.

What is today known as a full-length novel was first published in 1962 as various short stories. It was only in 1976 that the novel was published in its entirety. It is often referred to in blurbs on the various editions as “The Hugo Award winning novel,” but a close scrutiny of the Hugo Award winning novels reveals no such entry. That’s because the five stories that make up the novel, as a collection, won the 1962 Hugo Award for best short fiction, published in the following sequence in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, from February to December 1961:

GMRC Review: Deathbird Stories by Harlan Ellison

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the fourth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the fourth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

If there ever was a kind of excessive, unorthodox or hysterical posturing in SF, Harlan Ellison definitely embodies it. And not only in the choice of the titles of his impressive stories. He certainly has a flare for verbal thrift, rarely struggling to grope for effect, as Connie Willis may well atest to. Despite his outrageous actions that often include letigation of all kinds against an impressive cast of you-know-who’s, which I believe has a lot more to do with upholding a bad-boy image than anything else of substance, Ellison certainly is gifted with literary cleverness and as such is one of the most decorated writers in the genre, winning over 100 awards. He works almost exclusively within the short story form, and consequently has remained little known outside SF circles. Apart from editing the landmark Dangerous Visions anthology, and its follow-up Again, Dangerous Visions, Ellison also did some work on Star Trek, Babylon 5 and The Outer Limits, one episode of which named "Soldier" being the inspiration for The Terminator. True to form, Ellison sued.

If there ever was a kind of excessive, unorthodox or hysterical posturing in SF, Harlan Ellison definitely embodies it. And not only in the choice of the titles of his impressive stories. He certainly has a flare for verbal thrift, rarely struggling to grope for effect, as Connie Willis may well atest to. Despite his outrageous actions that often include letigation of all kinds against an impressive cast of you-know-who’s, which I believe has a lot more to do with upholding a bad-boy image than anything else of substance, Ellison certainly is gifted with literary cleverness and as such is one of the most decorated writers in the genre, winning over 100 awards. He works almost exclusively within the short story form, and consequently has remained little known outside SF circles. Apart from editing the landmark Dangerous Visions anthology, and its follow-up Again, Dangerous Visions, Ellison also did some work on Star Trek, Babylon 5 and The Outer Limits, one episode of which named "Soldier" being the inspiration for The Terminator. True to form, Ellison sued.

His best known collection is arguably The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World, which features the definitive New Wave story "A Boy And His Dog" that won the Nebula for best novella, and upsetting almost everyone, from liberals and feminists to the right wing alike, and of course, many of the Golden Age SF writers. After having read a few of Ellison’s stories, "A Boy and His Dog" remains his best, one of the few post-apocalyptic narratives to depict how raw and brutal existence after a nuclear holocaust would be – and equally successful in protesting and allegorizing the Vietnam War. Equally ingenious is Deathbird Stories, a collection probably closest to the horror genre, with an odd few elements of science fiction and fantasy thrown in.

As the subtitle, A Pantheon of Modern Gods, suggests, the theme is gods, and in particular the "new" gods (or devils) of our modern society. These are: the god of speed, the god of beauty, the god of money, the god of mechanical and technoligcal wonders, the god of apocryphal dreams and the gods of pollution. Even the god of the guilty, if there could be such a thing, albeit a Freudian trope. The stories are tied together by the concept that gods are real only as long as they have people who believe in them. We find echoes of this in Neil Gaiman’s phenominal American Gods. Ellison writes in the introduction:

"When belief in a god dies, the god dies… to be replaced by newer, more relevant gods."

It’s not a far-fetched assumption. Afterall, Thor and Odin disappeared when the Vikings took up the cross and Apollo was reduced to rubble along with his temples. Ellison offers a litany of dead gods. These 19 stories are essentially about the merits of religion and the religious and true to form, Ellison crushes eggshells in his usual confrontational manner, with a caveat lector at the beginning that warns the reader against reading the entire collection in one sitting because of the "emotional content:"

"It is suggested that the reader not attempt to read this book at one sitting. The emotional content of these stories, taken without break, may be extremely upsetting. This note is intended most sincerely, and not as hyperbole."

Despite there being an element of humor in some of these stories, the warning should not be taken lightly. It is not the usual Ellison arrogance at play here – they did exhaust and deaden my spirit. Still, Ellison’s missive does drive home the point that mankind is drifitng away from the belief in a benevolent, all-knowing, all-loving God and is instead transferring its faith to soulless pursuits and material possessions. There are truths present here, and some of them are very uncomfortable, taking the shape of monstrous, twisted forms, old creatures of myth like basilisks, gargoyles, minotaurs and even dragons, allegories for the new gods of gambling, the modern metropolis, pollution, sex, automobile showrooms and many other depraving endeavors. The gods appear to be a remarkably fragile lot.

These are my favorite stories from the collection:

"Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes" is about the god of the slot machine and the subsequent dead-end that Las Vegas could be. A similar kind of worship is found in "Neon," about a guy who seeks carnal knowledge with neon lights.

"Along the Scenic Route" is a narrative about a freeway autoduel of the future, very prescient to our modern day road-rage fueled obsessions on the world’s freeways.

"Basilisk" perspicaciously combines the Greek myth of a serpent-like creature with a lethal gaze and Mars, the hungry God of War. Lance Corporal Vernon Lestig does terrible things but I understood, and may even have sympathised with his reasons.

"On the Downhill Side" is just a beautiful and touching story about two ghosts who meet on a street in New Orleans. The God of Love allows them one more chance to find love in each other’s arms. The man had loved too much, leading to multiple divorces and his ultimate suicide, and the woman had remained a virgin until her early death. There is a dire price to be paid, a sacrificial compromise "forming one spirit that would neither love too much, nor too little." I could not help feeling that this is probably how Ellison truly sees love and religion operating. An emotionally engaging story, perfectly paced – I simply loved it.

"Shattered Like a Glass Goblin" invokes the paranoid fears brought about by hallucinogenic drugs within the surreal atmosphere of a hippie retreat. I find this story a magnificent allegory on the all-consuming downward spiral of drug addiction, culminating in a final hallucination as deciphered symbol of the inevitable surrender of the main protagonist, who thinks he is a glass sculpture of a goblin and his girlfriend a werewolf. When he tries to talk to her for one final time, she attacks him and he shatters into a thousand pieces.

"Paingod," which is my clear favorite in the entire collection, is about Trente the Paingod, who delivers pain and suffering when and if necessary to each conscious being across all the universes, and decided one day to find out first-hand what pain feels like from a sculptor who has lost his ability to sculp. The harrowing conclusion that pain is a blessing because without it there can be no joy still reverberates strongly with me.

The three weakest stories for me are:

"Rock God" is a rather pedestrian affair, dated, with the frantic corruptness of the protagonist very stereotypical.

"At the Mouse Circus" which I can’t say anything meaningful except that it features the king of Tibet and a cadillac and that I have no idea what Ellison is trying to convey.

"The Place With No Name" has Prometheus in it, but much like the movie, disappoints with things I did not understand at all and other things that were only too clear. There is this somewhat shocking denouement: what if Jesus and Prometheus had been lovers, were aliens that felt strong and loving empathy toward earthlings and gave them gifts, only to be punished (and crucified) by the other gods for doing so?

A polarizing collection with this many narratives dealing more or less with the same subject matter is bound to have a few unappealing stories. Nonetheless, there are still other, brilliant and well crafted stories like the catchy "Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans: Lattitude 38° 54′ N, Longitude 77° 00′ 13" W" and the story the title is taken from, "Deathbird." I’m certain everyone who reads this collection will discover their own favorites. Take note of the caveat lector, though and read these divergent stories cautiously over a stretched period of time. They are hugely rewarding, even if exhausting. Ellision has always been a polemic figure who has never been afraid to articulate and share his opinions. This is true even of his writing. It is a difficult read, even painful at times, but as Ellison so expressly pointed out: what is joy without a little pain?

A polarizing collection with this many narratives dealing more or less with the same subject matter is bound to have a few unappealing stories. Nonetheless, there are still other, brilliant and well crafted stories like the catchy "Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans: Lattitude 38° 54′ N, Longitude 77° 00′ 13" W" and the story the title is taken from, "Deathbird." I’m certain everyone who reads this collection will discover their own favorites. Take note of the caveat lector, though and read these divergent stories cautiously over a stretched period of time. They are hugely rewarding, even if exhausting. Ellision has always been a polemic figure who has never been afraid to articulate and share his opinions. This is true even of his writing. It is a difficult read, even painful at times, but as Ellison so expressly pointed out: what is joy without a little pain?

GMRC Review: The Man Who Ate the World by Frederik Pohl

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the third of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the third of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Although Frederik Pohl‘s work began in the Campbellian era, he has always helped to determine the future of the genre through measured work as an editor, anthologist and writer. He began his career as a magazine editor in 1940 and wrote extensively with Jack Williamson and C. M. Kornbluth.

Although Frederik Pohl‘s work began in the Campbellian era, he has always helped to determine the future of the genre through measured work as an editor, anthologist and writer. He began his career as a magazine editor in 1940 and wrote extensively with Jack Williamson and C. M. Kornbluth.

With Kornbluth he produced the classic The Space Merchants (1953), which describes a future world dominated by advertising, a theme preceded here by a few years in the stories "The Wizards and the Waging" and "The Waging of the Peace", taking a "slickly ironic" look (to quote John Clute from The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction) at how humans react to everyday commercial products pushed into their faces. It’s incredibly fun to read about how the National Electro-Mech fortified factory inundates a small town Buick salesman with new Buicks and how the very same salesman ends up as a recruit in attacking and stopping the production of these cars. These final two stories, arguably the best in the collection, are slightly anti-capitalist satire. Nothing strange here, considering Pohl’s short foray in the Young Communist League during the late 1930s. Shortly hereafter – as a side note – he enlisted in the army, and, in weird twist of fate, served with Jack Williamson as a weather observer.

The title story "The Man Who Ate the World" is the weakest in the collection and is the only one I remember reading as a youngster. It’s a tragic story about this child growing up and trained to consume and consume, without his parents nurturing him. This important part of early childhood development is left to robots. Eventually, as an adult, he continues to consume and build robots to produce robots that destroy robots, ever repeating the cycle of consumption, ultimately threatening the existing world order. A psychologist comes to the rescue, reuniting the adult child with his teddy. Yeh, yeh, a cop-out and archaic Freudian psychology, but I did say this is the weakest story in the collection. It does not detract from Pohl’s more than subtle jab at American consumerism, that expectation for people to consume, buy, and destroy in order to repeat the cycle. Despite my gripe about the teddy, the story is still fun… and its insinuation certainly still rings true for modern day consumerism.

"The Snowmen" is my personal favorite, at 8 pages the shortest in the collection, and most bizarre, even cadaverous, hinting at a certain Roald Dahl chromaticity. Pohl skillfully unfolds the whole allegory in which in courting couple invites an alien visitor into the woman’s home. Her reputation, it seems, is well-known throughout the existing universe. While she entertains the alien, the man plunders and loots the alien craft, with a wonderfully macabre twist at the end.

"The Day the Icicle Works Closed" is about economic manipulation and collapse. A distant planet is cut off from trade and most people resort to renting their bodies to tourists while their minds perform hard labor elsewhere, usually inside gigantic machines, underground, in mines. The scientific mechanism on just how this happen is not explained, but that isn’t the point, is it? Pohl sets up a society that is forced to survive through disagreeable means because of economic disparity. So we see some ex-factory workers attempting to kidnap the mayor’s sons for ransom instead of whoring out their bodies to reckless and inconsiderate tourists. Ever considered your own behavior when driving a rental?

"The Day the Icicle Works Closed" is about economic manipulation and collapse. A distant planet is cut off from trade and most people resort to renting their bodies to tourists while their minds perform hard labor elsewhere, usually inside gigantic machines, underground, in mines. The scientific mechanism on just how this happen is not explained, but that isn’t the point, is it? Pohl sets up a society that is forced to survive through disagreeable means because of economic disparity. So we see some ex-factory workers attempting to kidnap the mayor’s sons for ransom instead of whoring out their bodies to reckless and inconsiderate tourists. Ever considered your own behavior when driving a rental?

In Pohl’s novels Jem: The Making of a Utopia (1979) and Man Plus (1976) we meet characters who adapt to their strange environments by losing, or changing their humanity. Although "The Seven Deadly Virtues" do not address the exact same issues we do recognize similar themes. The story is set on Venus and I can’t imagine a harsher environment to live in. It’s an interesting society featuring a conditioning response to killing – you simply cannot do it. That aside, once you have acclimatised fully to conditions on Venus, there is no leaving. And once society has shunned you, you become a non-person. This happens to a relative new arrival to Venus, who steals the wife of a very powerful man, resulting in his ostracization. Someone else, also shunned, is included in the plot to topple the powerful man. The solution is masterfully done and very plausible.

All in all, this is a stunning collection of six short stories by a master storyteller, and despite them being dated by 50+ years, still quite unique and remarkably prescient, generally poking fun at mass production, consumerism and industrialization. These stories of social criticism were a blast and expose Frederik Pohl as the hidden hero of SF. Think of him in terms of the Golden Age. He knew them all – who else is still alive?

GMRC Review: A Time of Changes

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the second of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the second of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

In the mid-1960s we find many established genre writers starting to produce more mature and more literary fiction, culminating – amongst other brave and ground-breaking concerns – in significant stories criticizing militarism and the neo-imperialism agendas of the then US foreign policy, a trend that reached its peak with Grand Master Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War. This novel swooped most of the awards at the time and expressed just how successful the New Wave’s ideological platform had been. Arguably, the legacy of the New Wave remains inconclusive, considering the still on-going debates about the supposed “ghettoization” of the genre. Robert Silverberg is an exponent of the New Wave. Initially a prolific writer of “routine” SF in the 1950s, he began to produce some of the most interesting works in SF during this period, such as Thorns, The Masks of Time, Tower of Glass and A Time of Changes, which went on to win the Nebula Award in 1971. I have never read it before now.

In the mid-1960s we find many established genre writers starting to produce more mature and more literary fiction, culminating – amongst other brave and ground-breaking concerns – in significant stories criticizing militarism and the neo-imperialism agendas of the then US foreign policy, a trend that reached its peak with Grand Master Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War. This novel swooped most of the awards at the time and expressed just how successful the New Wave’s ideological platform had been. Arguably, the legacy of the New Wave remains inconclusive, considering the still on-going debates about the supposed “ghettoization” of the genre. Robert Silverberg is an exponent of the New Wave. Initially a prolific writer of “routine” SF in the 1950s, he began to produce some of the most interesting works in SF during this period, such as Thorns, The Masks of Time, Tower of Glass and A Time of Changes, which went on to win the Nebula Award in 1971. I have never read it before now.

A Time of Changes is clearly a literary experiment. And – sadly, dare I say – very much a product of its time. Don’t get me wrong – I did like the book, but even recognising the fact that it is a story from its decade, I feel it’s quite dated.

It is a simple story that deals plausibly with a variety of complex issues. The setting is that of a future society on the planet Borthan, earlier colonised by members of a religious sect. They followed a set of theological guidelines called the Covenant, which prohibited one from opening your heart and mind to others, essentially then, the denial of self. It is meant to prevent individuals from placing their personal burdens on others, to the extent that a ban is placed on the use of first-person pronouns. Referring to one self as “I” is a terrible breach of manners and has both dire social and legal consequences. The act of “self-bearing” is the ultimate sin, as our narrator informs us himself:

Obscene! Obscene! Already on the one sheet I have used the pronoun “I” close to twenty times, it seems. While also casually dropping such words as “my”, “me”, “myself”, more often that I dare to count. A torrent of shamelessness. I I I I I. If I exposed my manhood in the Stone Chapel of Manneran on Naming Day, I would be doing nothing so foul as I am doing here. (Orb edition 2009, page 17-18)

We see that not everyone on Borthan embraces the Covenant. The opening sentence “I am Kinnall Darival and I mean to tell you all about myself” introduces the reader to someone who eventually came to resist the Covenant. Kinnall continues to relate his experiences from early childhood onwards to this exact point where he can write his self-bearing sentence. We meet him as a prince in the province of Salla, the younger son of the prime septarch on Borthan. Tradition dictates that he has little chance of becoming septarch himself and therefore he decides to leave his home upon his father’s death. He wanders for years before making a home in the southern province. Here Kinnall meets an earthman who challenges his early assumptions about his society and convinces him to take a wonder drug that breaks down the barriers between human minds through a telepathic experience. This act changes Kinnall from a staunch bureaucrat into a prophet of self-bearing, with some tragic consequences, and ultimately leads to his self-imposed exile in the Burnt Lowlands.

I generally enjoy this type of narrative, and was often reminded of Severian’s odyssey in Gene Wolfe’s seminal The Book of the New Sun. Silverberg does a splendid job with the internal conflicts of someone who challenges the very fabric of their society and comes to question the basis of their world and its religion. Kinnall is a strong, often courageous, inquisitive character and, judging by this first-person narrative, very introspective. But, like Severian, he is also notably fallible, appalingly arrogant and destructively selfish – these traits finally lead to an unexpected tragedy near the end as he proceeds to spread the drug and the new way of thinking about his world. Silverberg handles Kinnall’s downfall with consummate skill. One can be forgiven for equating this downward spiral to the predictable calamity of established drug addiction. Perhaps, in some preternatural sense, Silverberg has crafted an ingenious rebuke against the unchecked drug use of this period.

I do have some problems with the book. The Orb edition (2009) that features an explanatory, contextual preface by Silverberg, also, thankfully, had a map. Without this map, the lengthy descriptions of the geography of Borthan and the imaginary names would have been totally lost on me. Despite the wonderfully crafted world-building in true Silverberg tradition, it had little relevance for me to the story. Well, maybe Kinnall’s exile in the Burnt Lowlands and its accompanied descriptions is perhaps an exception, as symbolic of his downfall, the ultimate destination of his personal odyssey. A big part of the book is therefore little more than world exploration and adds to the surface appearance of just an elementary story about just another drug. Yes, Silverberg’s writing is exceptional, intriguing and euphonious, but it ultimately doesn’t save the story from all the tedious musings and descriptions. At times it felt dull and lackadaisical – the story could have done with some trimming. It never really shifted past first gear.

In the preface Silverberg does acknowledge that since the publication of A Time of Changes he discovered other languages that avoided the construct “I”. It might have appeared a unique literary device at the time, but let’s not forget that Samuel R. Delany has attempted the same in Babel-17. The story would have been so much stronger if Silverberg avoided using the construct “one” all together; it is nothing else but a mere replacement of the pronoun “I”. Why bother? People were still referring to themselves directly. It would have been less artificial if he remained within the constructs of what we experience with Kinnall’s forlorn journey into Glin, where people actively avoid speaking about themselves at all, not even using the term “one”. And it is quite acceptable to refer to someone else as “you”, which felt equally contrived, for – unless I’m mistaken – “you” still implies a concept of “self”.

In the preface Silverberg does acknowledge that since the publication of A Time of Changes he discovered other languages that avoided the construct “I”. It might have appeared a unique literary device at the time, but let’s not forget that Samuel R. Delany has attempted the same in Babel-17. The story would have been so much stronger if Silverberg avoided using the construct “one” all together; it is nothing else but a mere replacement of the pronoun “I”. Why bother? People were still referring to themselves directly. It would have been less artificial if he remained within the constructs of what we experience with Kinnall’s forlorn journey into Glin, where people actively avoid speaking about themselves at all, not even using the term “one”. And it is quite acceptable to refer to someone else as “you”, which felt equally contrived, for – unless I’m mistaken – “you” still implies a concept of “self”.

It is a one-sided story, a telling from only Kinnall’s perspective. Don’t expect the opponents of self-bearing to be more than pitiable, brain-washed victims who will never know the true happiness that comes from sharing yourself with others. The story lacks a strong counter-protagonist and suffers greatly because of it.

In the final analysis, if you are looking for epic and multifarious adventures in Hard SF this book is not going to appeal to you. It is predominately a detailed character study with alluring exploration of an alien world and equally strange society that asks obstinate questions about the world around us. The first chapter and middle part of the book is engaging and exciting – pure Silverberg world-building, the remainder weaker, even disappointing. I find the book an important achievement in the history of SF, for its attempt to move away from technological explorations and pulpy space adventures into the challenging sub-genre of Soft SF, exploring difficult psychological and philosophical issues – and can appreciate why it won a Nebula Award, clearly an attempt to recognize the principles of the New Wave generation. I can’t say I agree with Silverberg’s conclusion, though. Self-repression does not need to be replaced by self-annihilation and the appearance that total intimacy is the best way through which to create a peaceful, happy society, is very naïve, typical of the idealism from that era. The idea of totally opening up to others with a certain reckless wantonness and allowing them into our minds in order to study our innermost thoughts, feelings and concerns is more than a little incommodious.

I’m glad to have read the book, but wanted to like it more. Silverberg has written much better novels, many of which did not go on to win an award.

Sources: Edward James, Science Fiction in the 20th Century. Opus (1994); Robert Silverberg, "Preface" in A Time Of Changes, Orb (2009)

GMRC Review: Powers by Ursula K. Le Guin

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, has gotten his January GMRC review in just under the wire. He’s an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, has gotten his January GMRC review in just under the wire. He’s an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com.

Powers is the third book in The Annals of the Western Shore, a YA series, with Gifts and Voices preceding it, and the only one that can be read as a stand-alone novel (hence my review for the GMRC, although Voices is to me the more accomplished and solid book of the series). However, the ending will be much more meaningful if all three were read in sequence. The books are loosly connected by a couple of characters, Orrec and Gry – we meet them as children in Gifts, and finally as adults in the final chapter of Powers. The seperate stories are set in geographically dispersed areas of the Western Shore and concern characters with different magical abilities, or gifts. The gifts are what make the families of the Uplands different, and even feared as witches by Lowlanders.

Powers is the third book in The Annals of the Western Shore, a YA series, with Gifts and Voices preceding it, and the only one that can be read as a stand-alone novel (hence my review for the GMRC, although Voices is to me the more accomplished and solid book of the series). However, the ending will be much more meaningful if all three were read in sequence. The books are loosly connected by a couple of characters, Orrec and Gry – we meet them as children in Gifts, and finally as adults in the final chapter of Powers. The seperate stories are set in geographically dispersed areas of the Western Shore and concern characters with different magical abilities, or gifts. The gifts are what make the families of the Uplands different, and even feared as witches by Lowlanders.

Le Guin is in familiar territory when telling Gavir’s story. Like the previous books, the narrative is told from the first-person perspective. Gavir is the house slave of a wealthy, cultured and relatively enlightened and benign family in a town called Arcamand. He has two gifts, the ability to see events that have not yet happened, as a "memory," and the ability to remember anything he has read, able to recite the complete story verbatim. One is clearly supernatural, the other, arguably, not. In the end, though, the magical abilities are less important than the social circumstances of the characters. A thread seems to run through the series: a reluctance, perhaps even a fear, to use these gifts. The question is one of power and the consequences of its use and misuse and of choice. Towards the end, when Gavir is tutored by Dorod, this choice becomes brutaly clear: control and use the power and accept the cruelty that it brings, or find another way. Wisely, early in the book, Gavir’s sister convinces him to never reveal his abilities. It is not a spoiler to reveal that Gavir does find another way.

Initially all is well. Gavir is truly happy and content with life, albeit a life badly distorted by the mechanisms of organised slavery. The first section of the book is clearly recounted by a priviliged slave living in far better conditions generally associated with his kind, even to the extent that he may go to school. With subtelty that’s almost cogent, Le Guin unravels the true nature of the oppressive society, showing just how capricious the amity of the household can be, and how utterly dangerous Gavir’s trust in his owners is. As his character develops, Gavir gradually comes to understand and accept even the betrayal of his trust. At this point Le Guin demonstrates yet again the range and depth of her artistry as Gavir informs us:

"It grieves me that blind hate and rancour should be my last link to Arcamand. I could think now of the people of that house with gratitude for what they had given me – kindness, security, learning, love. I could never think that Sotour or Yaven has or would have betrayed my love. I was able to see, in part at least, why the Mother and the Father had betrayed my trust. The master lives in the same trap as the slave, and may find it even harder to see beyond it. But Torm and his slave-double Hoby never wanted to look beyond it; they valued nothing but power, the most brutal control over people. My escape, if he heard of it, would have rankled Torm bitterly. As for Hoby, always seething with envious hatred, the knowledge that I was going about as a free man would goad him to rageful, vengeful persuit" (page 355, Orion edition 2008).

Where Gavir once may have believed that a social order of master and slave is the natural way of things, he slowly begins to percieve the true injustice of it, and when a horrible tragedy strikes, his life begins to rapidly change. Almost by accident Gavir escapes his slavery, and the narrative transforms into a compelling and riveting journey with equally compelling characters. When Gavir takes to the road, heading back to his people, it’s the beginning of his coming of age journey. He must try to understand the nature of his own talents, but always his past as a slave haunts him, like a shadow. Hoby, who once bullied him before he made his escape, ultimately after many years’ searching, tracks him down. The river crossing explained in a few short paragraphs remains for me one of the most touching and unforgettable narratives in all of Le Guin’s work, a symbolic crossing perhaps every child is destined to make.

"The way to go was plain at first, the clear water showing me the shallows between the shoals. Out of the middle of the water, I looked back once. The horseman had seen us. He was just riding into the river, the water splashing up about his horse’s legs. It was Hoby. I saw his face, round, hard, and heavy, Torm’s face, the Father’s, the face of the slave owner and the slave…. I saw it all in a glance and waded on, crosscurrent, pulling the child with me as best I could…. I knew where I was then. I had been in this river with this burden on my shoulders. I did not look around because I do not look around, I go forward, almost out of my depth, but still touching bottom, and there is the place that looks like the right way to go…." (pages 369-370, Orion edition 2008).

Le Guin’s metaphors and imagery and insights are no less powerful, no less beautiful. She can still create myths.

Le Guin’s metaphors and imagery and insights are no less powerful, no less beautiful. She can still create myths.

The final two chapters of Powers are just overwhelmingly moving, simply spectacular, and the reason why this series is now one of my favourites, alongside Earthsea. Gavir becomes a character to really like, endearing and respected, not only because of his love for scholarship and reading, but because of Le Guin’s remarkable and canny ability to remember and depict the crises and concerns of adolescence that could easily have been my story. Attentive readers will meet themselves and, sadly, the worst of the societies we live in.

Powers still resonates with me, long after I finished it. Le Guin’s familiar subjects and motifs are still present, as the all-encompassing political concern for the protection and the nurture of human freedom in all aspects of human life, and the urgent need for the creation of a real human community. This is a message I don’t mind young adults hearing. There is no miraculous conversion of slave owners, renouncing their evil, oppressive ways. Like life, there are no easy answers, but in the end, hanging on, things do get better. I, for one, do believe that.

Highly recommended, not only for young adults.

The Recursion Trilogy – Tony Ballantyne

The Recursion Trilogy by Tony Ballantyne

Tor – 2004-2006

Bantam Spectra – 2005 – 2007

Imagine this: Your brain has been removed from your body and placed in a vat of nutrients which keeps said brain alive. The nerve endings have been connected to a super computer which creates the illusion that everything is perfectly normal. The people, places and things you experience are in truth electronic impulses travelling from the computer to your disembodied brain. A nightmare scenario, straight out of The Matrix! But this is exactly what the philosopher Nick Bostrom suggests – that it is highly probable that we are already living in a computer simulation. We, of course, don’t think so. We’re not computer-simulated minds living in a simulated world. But that may just be a tribute to the quality of the programming!

The first book in the trilogy, Recursion, informs us right from the start that the series is about a god-like computer intelligence, the Watcher, and that we are dealing with the very same universe that Nick Bostrom has postulated. The antagonists are not certain whether they are in a real or simulated world. As a consequence, hard questions are asked about the right of individuals to self-determination and whether or not humanity should be “cured” from its delusion – for its own good, obviously. It becomes apparent that our main protagonist has been copied many times and inserted in many simulations. Ballantyne excellently sets this realization up through “programming” in blank spaces appearing between buildings and the ground. Amongst all this, a battle is raging and speculation starts on the origins of intelligence, and ultimately of the Watcher himself.

Capacity takes us a step further, literally a dramatic elaboration of the brain-in-a-vat scenario, focused on virtual environments and operating spaces alongside the “atomic world” whilst giving the impression that humanity is still in control. The Watcher is very much in the background here but his influence is felt throughout. Against the backdrop of a deceptively simple crime mystery, Ballantyne asks uncomfortable questions about free will, what constitutes intelligence in general, and life in particular. As with the first book, he rotates through three different viewpoints, ultimately combining them together towards a climax that sits slightly uncomfortably – the logic of machines is hard to comprehend.

The final book, Divergence, attempts to – amongst other things – address the problem of free will by trying to reconcile the view that humans are free agents and fully in control with a deterministic understanding of their actions. Every event has a prior cause. Every state of the universe is necessitated or determined by a previous state which is itself the effect of a sequence of still earlier states. Ballantyne builds this up with flashbacks of Eva’s past. Eva is one of the main protagonists and the object of the Watcher’s studies when he first emerged. It is not artificial intelligence, but the relationship with all AIs in the novel that becomes one of the key considerations that brings the protagonists together for the final showdown with the Watcher. Unfortunately, the final part of the story feels a little forced, as if Ballantyne was rushed to complete the series, and doesn’t fully deliver on its promise.

One of the central themes of the trilogy, which stretches across 250 years of human (and machine) evolution, is the concept of the Singularity. That nebulous point in the future when technological, scientific and economic change accelerates so fast that we cannot even imagine what will happen from our present perspective – a time when humanity will become post humanity, and we witness the emergence of legitimate Artificial Intelligence. Machines will outpace human minds, and – as is the case with Ballantyne’s universe – will govern humanity in what initially appears to be a utopian society. But things are generally not that simple as elsewhere another AI develops with very different views to the Watcher.

Added into the mix is a Turing machine that claims to not be an AI, many Von Neumann machines (self-replicating spider robots), an anti-AI organization named DIANA, Schrödinger boxes and cats, “Fair Exchange” software that is pure genius and ominous Black Velvet Bands. All in all, there is a lot going on and the complexity of Ballantyne’s universe is such that you’ll likely find yourself going to Google to clarify and explain some concepts. There is a finely-tuned “Big Brother is watching you” vibe with a liberal dose of drug-addled hallucinations in classic A Scanner Darkly tradition.

Considering the immensely complex subject matter, Ballantyne mostly succeeds in holding everything tightly together. There are a few frustrating moments where he resorts to info-dumping and many of his ideas are more memorable than his characters. Yes, it’s easy to get confused and a little lost in a plot which often-times over shadows the characters. Also, The Recursion Trilogy does not share the action sequences of The Matrix or such gritty, action-packed SF as Altered Carbon or Snow Crash and in the overall scheme of things, suffers a little for it.

Despite these flaws I still remained caught up in pursuing the mystery to its final conclusion. Ballantyne has put together an imaginative series, rich with thought-provoking ideas, some memorable characters and an enthralling storyline written in a confident, lucid prose. The Recursion Trilogy is seriously hard-SF, classic cyberpunk and is distinctly dystopian and I recommend it to anyone looking for “real” science fiction – so long as you don’t mind having to think about what you’ve just read. It’s a riveting premise and I look forward to reading Ballantyne’s Robot Wars saga with a great deal of anticipation because of it.

Embedded – Dan Abnett

I am a Dan Abnett novice. I’ve never read anything out of the Warhammer 40K universe. This is probably a blessing in disguise. Reading Embedded, I was not polluted by inevitable comparisons to his syndicated work; I could read it wholly in the context of a setting entirely Abnett’s own. As a result, I was more than pleasantly surprised.

Embedded is a tough, near-future, military-sf novel of the highest quality. With a serious story about people caught up in a warzone, Abnett has skillfully created the ultimate eyewitness account of a military struggle that features persuasive allusions to the current situation in Afghanistan and past conflicts in Iraq. In the process he succeeded in creating a very authentic universe with his own blend of unique but not unbelievable military technology, corporate sponsorships and analogous architecture, synthesized food items that taste like the original and even filtered language that is the cause of much amusement throughout the storytelling. It is solid world building with wonderful attention to detail.

Having a journalist’s consciousness embedded into the synapses of a soldier’s brain is an unprecedented innovation and sets up a rite of passage truly comparable to Starship Troopers and The Forever War. Pitch in Abnett’s gripping, engaging and fluent writing style and an uncanny ability for seamlessly connecting the various pieces together with near-perfect timing and pace, it was easy to imagine watching the same grainy, documentary footage shot by embedded reporters so often seen on television. This is a book with movie written all over it!

Embedded starts off slowly, almost a trudge, as if Abnett purposefully wanted to relay just how exceedingly dull and dreary planet Eighty Six seems on its surface. Initially there is very little to engage with. Falk, the main character is, at the outset, a dislikeable, clichéd reporter with boorish and egotistical manners. After about 90 pages though it becomes evident that all is not what it seems to be. Despite the military’s spin on events there is a very ruthless war going on here, but it is not immediately clear why. Abnett sets up various red herrings as possible answers to this enthralling question that demands you stick around ‘till the end. Audaciously, he only reveals the true answers right at the very end after putting the reader through many remarkably anxious combat scenes and the ensuing emotional turmoil of the characters. The relationships between the soldiers and Falk’s own rite of passage after his “host” is shot are written with believable clarity. These character developments are especially satisfying and the particular journey that Falk undergoes totally redefines his character to the extent that he becomes worth following. Ultimately very little remained of the cantankerous and obnoxious Falk I met in those first few pages.

Nothing in the novel felt contrived. Yes, there are some uncomfortable questions raised about the way Abnett presents the “remote controlling” of a corpse but these are soon forgotten once the many action scenes present themselves. With these, Abnett’s adroitness is beyond contention. He has a pronounced skill and flair in creating anticipation, tension and release balanced with immaculate timing, pace and the unexpected. The battle scenes are terrifyingly realistic and intentionally chaotic. War is not a pub brawl and Abnett unquestionably does not treat it lightly.

The novels denouement is arguably its only weak point. Despite everything tying together rather well, lifting the veil on the overarching vagueness, I find the final revelation a bit convenient and a typical science fiction “exit.” But it does not detract from what Abnett ultimately wants to say: that every war, fought for whatever reason, reduces the stock of human good, and diminishes civilization. The last, short chapter brought this home for me.

Embedded is pulsating military-sf, cynical but not jaded, ruthlessly brutal yet intelligent. An impressive and very satisfying read.

Starship Troopers

Very few science fiction novels have aroused such controversy over the decades as Starship Troopers by Robert A. Heinlein. This militaristic epic, winner of the 1960 Hugo Award, has been accused not merely of glorifying military values but of endorsing fascism to the point that one could say that the Terran Federation is analogous to Nazi Germany. An extreme analysis of course, which in our post-modernist world is terribly unfair, but there is no denying that Starship Troopers is indeed a pseudo-Darwinian rationale for an endless inter-species war of all against all. The novel, as it stands accused by many critics, rapidly degenerates into a series of lectures about politics, history and philosophy by way of various mouthpieces; and reverberates “that Heinlein voice.”

Oddly, I still found it compelling and stimulating, taking an interest in its political and moral philosophy rather than being converted to what is advocated in the text. It’s actually quite far from the fascism it is accused of. Anyone who can understand the oath may serve, regardless of their attributes or abilities. There are no wars within the human species, with lots of personal freedom, where almost everyone is reasonably well off and people who despise the government can do so openly and fearlessly.

A student of history will notice that the communal ideology of the alien “Bugs” is virtually identical to Western Cold War understanding of Communism and the Soviet Union. There is a delightful, explicit critique of Marxism as Rico concludes at one point:

“We were learning, expensively, just how efficient a total Communism can be when used by a people adapted to it by evolution; the Bug commissars didn’t care any more about expending soldiers than we care about expending ammo.”

Virulent anti-Communist! Undoubtedly right-wing in its politics and unashamedly militaristic but also one of the finest coming-of-age narratives in science fiction. We follow Rico’s rites of passage, making many mistakes along the way, and contrary to a glorifying view of war, avoiding blind heroism. (Don’t ever confuse the book with the movie sharing the same name!)

It is undeniably a significant work in the history of the genre, pioneering an entire sub-genre of military space opera, even if only paradoxical in that many, like Joe Haldeman and Orson Scott Card, have written fiction in conscious opposition to the philosophy espoused in Starship Troopers.

“To the everlasting glory of the infantry…”

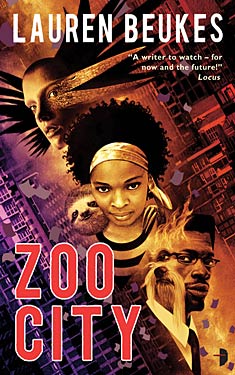

10 Questions – Lauren Beukes

Lauren Beukes is the author of Zoo City, a pseudo-fantastical, hardboiled and gritty thriller about crime, magic, the music industry, refugees and redemption set in a re-imagined Johannesburg. It has been nominated for both the 2011 Arthur C. Clarke Award and the 2010 BSFA. The novel already won the Kitchies Red Tentacle for the 2010 book that “best elevates the tone of geek culture.” Moxyland, her first novel, set in a not-so-distant futuristic Cape Town (where she lives), is a haunting vision of what corporatocracy can be. Her non-fiction Maverick: Extraordinary Women From South Africa’s Past (Oshun 2005) was long-listed for the 2006 Sunday Times Alan Paton Award, and tell the real-life stories of raconteurs and renegades, writers, poets, provocateurs and pop stars, artists and activists and a cross-dressing doctor.

Ms Beukes was kind enough to answer a few questions about her novels.

EJ: First, let me congratulate you on the Red Tentacle, and the nominations for the Clarke and BSFA awards. Both your novels have received wide acclaim and rave reviews. Was this anything like you expected when you wrote them?

LB: You always hope, nervously, that your books are going to be able to hold their own when you send the scrappy little darlings out on their own into the big bad world. But it’s tremendously gratifying – and humbling – when the reception is so overwhelmingly positive. (And grounding when it’s not – as was the case at my mother-in-law’s 75th birthday when one of her very nice elderly friends turned to me and said, “I did try to read your book, but it was really just impossible.”)

EJ: Which authors and what books have most influenced your writing, structurally and stylistically?

LB: David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, William Gibson’s Pattern Recognition, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx & Crake, Alan Moore’s Ballad of Halo Jones, Watchmen and V for Vendetta, Philip K Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, Lorrie Moore’s short stories, TC Boyle’s Tortilla Curtain, Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, Paul Hoffmann’s The Wisdom of Crocodiles, Joyce Carol Oates’s anything, William Boyd, Haruki Murakami.

I think what those things have in common is gorgeous writing serving smart, inventive and ultimately surprising stories.

EJ: Both Moxyland and Zoo City are first-person narratives – in fact Moxyland has 4 different first-person perspectives. How did you decide you were going to write in first-person? Do you have a preference for first-person narratives in your own reading?

LB: It just happened that way. I like the immediacy and presence of first person fiction. It’s not something I actively seek out in my reading or my writing. I think the new book is going to be third person, but we’ll see.

EJ: Moxyland was your debut novel, but not your first book. In 2005 you published Maverick: Extraordinary Women From South Africa’s Past. What inspired you to switch gears from history to science fiction? Do any of your fictional characters borrow from the historical figures you’ve written about? Zinzi is most assuredly an extraordinary woman.

LB: I was commissioned to write Maverick by the publisher based on what she’d read of my journalism. But I’ve always loved history and it was great teasing out the narrative of these extraordinary women’s lives, particularly as I got to choose the line-up, which ranges from a street-fighting jazz chanteuse to a serial poisoner to a glam commie journo revolutionary.

I’m sure those histories have seeped into my subconscious, but I haven’t knowingly whipped them out.

Zinzi’s a mash-up of people I know and some parts of me and wholly herself.

EJ: Moxyland is a dystopian cyberpunk novel whereas Zoo City would be considered an urban fantasy. Both are novels that many would consider a hard sell in South Africa where much of the literature is dominated by the apartheid experience. How has apartheid affected or informed your fiction? Where does your brand of science fiction fit into the broader South African context? Is there a future for a uniquely South African brand of science fiction?

LB: Phew. I think traditionally they probably would have been a hard-sell. To generalize horribly; South African literature was very focused, necessarily on apartheid and it’s aftermath for a long time. I think we’ve got most of that out of our system, but that’s not to say it’s not still relevant. I think of both Moxyland and Zoo City as apartheid novels. Moxyland is a neo-apartheid state, a what-if about how easy it would be to slip back into that space. Zoo City deals with artificially imposed segregation of the animalled versus ordinary people, refugees and rich vs. poor, which is very much the state we’re in at the moment – economic apartheid between rich and poor with the divides growing bigger every day.

I don’t know where it fits in or even if it is a particular brand of science fiction. I hate labeling because it wedges books into boxes that immediately cuts off part of your potential audience who get freaked out by the shape of those boxes. Can I come up with my own labels? Zoo City is muti noir and Moxyland is future urban thriller.

I do think there is more space to play and I’m very excited by some of the new releases coming out of SA like Lily Herne’s slyly political YA zombie apocalypse novel, Deadlands or Adeline Radloff’s time-travelling superhero romp, Side-Kick or SL Grey’s horror, The Mall – all of which have a smart, subversive, socially-aware edge. It’s a necessary reflection of where we’re writing about, I think, that we’re all keenly aware of it.

EJ: Zoo City is a hardboiled stranger-than-fiction story with many layers and some proverbial “monkey on your back” symbolism. What is Zoo City really about? What do you want your readers to take away from your story?

LB: It’s about guilt and the possibility of redemption, how we’re burdened by the past and how that affects our future. It’s very much about crime, but again, also about apartheid. The thing at the end (no spoilers here) is that thing for a very particular reason and it ties in to our recent history.

EJ: What were the particular influences for Zoo City? I’m thinking in particular of the belief in mashavi, which not many international readers would be familiar with. Where did your research take you?

LB: Sjoe. I’m inspired by everything. I’m a pop culture sponge. I was very interested in the idea of crime and punishment, guilt and redemption, the music industry and pop factories that churn out wholesome teen pop stars and what that does to them (and here I raided some of Brenda Fassie’s history – one of the women of Maverick) and how different belief systems play out, especially muti (African magic – which can be benign herbalism or gruesome rituals performed with human body parts) and how South Africans would interpret a new global phenomenon in a uniquely South African way.

The idea of magical animals crops up in a lot of different cultures, from the ancient Israelites scape goats to the totem animals of some Native American tribes to Jiminy Cricket, the idea of the monkey on your back. I was reading a lot of South African mythology and I found the idea of mashavi. Ancestor-worship is a big part of traditional black South African beliefs and the mashavi are spirits that have become lost who manifest themselves as an animal that sometimes attaches itself to a person to good or ill effect.

In the book, everyone has a different theory about the animalled (as we have different theories in the real world about what happens after you die) but no real answers. Mashavi was an authentically South African take on that.

The research took me to some very interesting places, from visiting the Central Methodist Church to meet refugees sheltering there to walking round Hillbrow talking to people to interviewing music producers and having a consultation with a sangoma (or traditional healer) at the Mai Mai traditional healers market. She said I had a dark shadow over my life and prescribed the ritual sacrifice of a black chicken to get rid of it. I politely declined.

EJ: Your characters are very well developed. Zinzi December, in particular, is extremely well-written, with palpable conflicting desires and motivations. She’s often dishonest and she certainly doesn’t always make the best decisions. She gets run through the wringer on quite a few occasions – as do the characters in Moxyland. How attached do you get to your characters and do you ever feel bad about what you put them through? Did you know Zinzi’s fate when you started to write Zoo City?

LB: Thank you. I try to create complex, interesting, flawed characters. Sometimes the flaws make them frustrating – there were times I wanted to shake Tendeka in Moxyland, for example, for being so blinded by his self-righteous anger, but it’s true to the character.

And yeah, I do terrible things to my characters. I’ve had readers write me angry emails about Moxyland in particular, saying “how could you!” But I knew from the moment I started writing it which way it was going to go and what was going to happen to that character. It’s not my fault. The story demands it.

EJ: Your publisher, Angry Robot, is an up and coming genre specialist and Moxyland was one of their very first publications. Tell us a little about this history and your reasons for going with, what was then, a startup publishing house.

LB: I spent a year tentatively shopping Moxyland around to international agents and getting my soul crushed in the process. Then I took it to Jacana, South Africa’s most provocative and interesting and forward-thinking publisher who snapped it up right away, literally. The publisher, Maggie Davey read the manuscript on the plane on the way to the Frankfurt Book Fair and by the time she landed I had a book deal.

The book did well in South Africa and got some rave reviews, so I cowgirled up and started sending it out again. It was rejected by a slew of literary publishers who generally had very encouraging things to say and then it landed with Angry Robot who were then Harper Collins’ brand new edgy-as-fuck SF imprint who came back fast and hard with a two book deal.

I really liked the way they handled themselves in emails. There was no bullshit, no run-around and they really got the book. They’ve done wonders with it. I’m so impressed with their list generally and the way they’ve built an outspoken and loyal community through clever use of the Interwebs.

EJ: Moxyland and Zoo City each feature different covers for their South African and international editions. Did you have any say in their design? Are you satisfied that they relay the proper feeling and context of your stories?

LB: I was lucky to hand-pick my cover designers and I think they both did an amazing job in their very distinctive styles and really respected the spirit of the work and worked closely with me to get the right tone and feel. They were amazing to work with and gave me lots of opportunity to provide feedback. Interestingly, both were working from the same set of reference pictures – photographs I’d taken of Hillbrow on my cell phone camera and images of people I’d found online that I felt evoked a sense of the characters I’d written. Joey Hi-Fi’s black and white cover is evocatively beautiful and incredibly detailed with lots of Easter eggs about the plot within. John Picacio did an amazing job of portraying a kick-ass black female protagonist and he got Zinzi’s sass exactly right.

EJ: What can you tell us about any current projects you’re working on? What can we look forward to from here? Will you continue to set your fiction in South Africa?

LB: I’m working on a new novel – an apartheid thriller tied in to the real-life Occult Crimes Unit, with several other novels sitting on the backburner and practically boiling over already (really need to finish this one so I can get to them).

I just directed a documentary called Glitterboys & Ganglands about the biggest female impersonation pageant in South Africa, Miss Gay Western Cape, which will hopefully be debuting at the Encounters Festival in Cape Town.

And I’ve written my first comic (so excited), a nine pager for Vertigo’s Strange Adventures anthology due out May 25th.

EJ: I really appreciate your time in what I can only assume to be generally quite a hectic schedule. Thank you for participating in this interview and giving us further insights into your work. I for one am eagerly anticipating your next book and hold thumbs for a Hugo nomination in the near future. Judging by the laudable responses to Zoo City, I’m certain that possibility is not too presumptuous. The book is positively one of my favorite novels of all time and Moxyland a very close second.

LB: Thanks so much. I always get very shy around praise and my kneejerk response is to self-deprecate like crazy. But it’s the people who connect with your work who make it mean something. So thank you.

You can follow Lauren on twitter @laurenbeukes and stay up to date with her comings and goings by visiting http://laurenbeukes.book.co.za/

Full Details

Full Details