WoGF Review: Grass by Sheri S. Tepper

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

I was hoping to find the time to take part in the WWEnd Women of Genre Fiction reading challenge this year. Until now that has been a dismal failure. I haven’t had time to research and acquire the book I need for it and have mostly been reading stuff that was already on the to read stack this year. I would be surprised if I could still manage to read the twelve required but I can at least read some of them. After the reading challenge for 2013 was announced I picked Sheri S. Tepper’s novel Grass to be my first read. Tepper is a prolific writer in various genres and this novel is one of the few written by a woman that made the Gollancz science fiction Masterworks series when they were still being numbered. I have absolutely no experience with Tepper’s writing but the premise looked interesting so this novel was a logical place to start. The novel didn’t quite turn out to be what I was expecting but it is a very good read nonetheless.

I was hoping to find the time to take part in the WWEnd Women of Genre Fiction reading challenge this year. Until now that has been a dismal failure. I haven’t had time to research and acquire the book I need for it and have mostly been reading stuff that was already on the to read stack this year. I would be surprised if I could still manage to read the twelve required but I can at least read some of them. After the reading challenge for 2013 was announced I picked Sheri S. Tepper’s novel Grass to be my first read. Tepper is a prolific writer in various genres and this novel is one of the few written by a woman that made the Gollancz science fiction Masterworks series when they were still being numbered. I have absolutely no experience with Tepper’s writing but the premise looked interesting so this novel was a logical place to start. The novel didn’t quite turn out to be what I was expecting but it is a very good read nonetheless.

In a far future, overpopulation and environmental degradation have forced humanity into space. Many planets have been colonized but under the influence of humanity’s main religion the expansion has stopped for the moment. One of the colonized planets is named Grass. Most of its surface is covered with numerous species of a genus that resembles the grasses of old Earth. Despite its position at a galactic crossroad, the planet has remained something of a backwater, governed by a small group of families descended from various noble families in Europe. The ‘bons’ as these families are known would rather be left alone but when a plague strikes humanity for which no cure can be found, eyes turn to Grass anyway. For some reason, the population on Grass appears to be immune. Reluctantly, the bons allow an embassy on the planet to look into the matter.

GMRC Review: Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his tenth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his tenth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Editor’s Note: Val posted this review two months ago and we missed adding it to the blog at that time.

Last month I ran a poll to help me decide which book should be reviewed work number 300 on Random Comments and tied it to the Grand Master Reading Challenge for which I still have to read a couple of novels. Ray Bradbury won. I had expected one of the big names I hadn’t covered it to get it, perhaps Jack Vance or Robert Heinlein but, as one commenter pointed out, with Bradbury’s passing at the age of 91 just a few months ago, perhaps it is not so surprising he come out the favourite. I haven’t read anything by Bradbury before so I figured I’d read the book he is best known for. Fahrenheit 451 was published in 1953 so it’s too old to have won any of the major science fiction awards but it has been added to countless list of best books in science fiction and is well regarded outside the genre. It is one most influential dystopian novels, often mentioned in one breath with Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World. In short, a book with quite a reputation.

Last month I ran a poll to help me decide which book should be reviewed work number 300 on Random Comments and tied it to the Grand Master Reading Challenge for which I still have to read a couple of novels. Ray Bradbury won. I had expected one of the big names I hadn’t covered it to get it, perhaps Jack Vance or Robert Heinlein but, as one commenter pointed out, with Bradbury’s passing at the age of 91 just a few months ago, perhaps it is not so surprising he come out the favourite. I haven’t read anything by Bradbury before so I figured I’d read the book he is best known for. Fahrenheit 451 was published in 1953 so it’s too old to have won any of the major science fiction awards but it has been added to countless list of best books in science fiction and is well regarded outside the genre. It is one most influential dystopian novels, often mentioned in one breath with Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World. In short, a book with quite a reputation.

Fahrenheit 451 is a dystopian novel set in a future America where books are outlawed and a fireman’s job is to burn them instead of putting out fires. One such man is Guy Montag, who unquestionably burns books, the source of all dissent in society. Until he meets the 17-year-old Clarisse that is. She talks to him about ideas that make no sense and about doing things that no rational, we ll adjusted man should even consider. She makes Montag thing and without him understanding why, he develops an aversion against his job, starts questioning his life and develops a curiosity about books. Montag is in trouble.

GMRC Review: The Listeners by James E. Gunn

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his tenth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his tenth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

I haven’t been very adventurous in my reading for the Damon Knight Grand Master reading challenge. Seven of the ten books I’ve read so far have been by authors I have read other works of, while two others were acknowledged science fiction classics. For the eleventh read I decided to pick a book by someone I knew very little of. James Gunn doesn’t have as long a bibliography as some of his contemporaries and quite a lot is short fiction. He made quite an impact on the genre nevertheless. Besides writing, Gunn is a noted critic and teacher as well as the director of the Center for the Study of Science Fiction. The Listeners (1972) is a fix-up novel, various parts of it appeared in Galaxy Magazine and Fantasy and Science Fiction between 1968 and 1972. It is probably his best known novel, but apparently not one instantly recognized as a masterwork. Gunn missed out on all awards and nominations save one for the Campbell award in 1973. There have been a whole bunch of editions of this book with different forewords, introductions and afterwords. The copy I’ve read is a 2004 edition which features an introduction by H. Paul Shuch, an American physicist heavily involved with SETI, a foreword by Thomas Pierson, founder of the SETI Institute, and and afterword by the late Freeman J. Dyson, British-American mathematician and physicist. I guess this book is still well loved in scientific circles.

I haven’t been very adventurous in my reading for the Damon Knight Grand Master reading challenge. Seven of the ten books I’ve read so far have been by authors I have read other works of, while two others were acknowledged science fiction classics. For the eleventh read I decided to pick a book by someone I knew very little of. James Gunn doesn’t have as long a bibliography as some of his contemporaries and quite a lot is short fiction. He made quite an impact on the genre nevertheless. Besides writing, Gunn is a noted critic and teacher as well as the director of the Center for the Study of Science Fiction. The Listeners (1972) is a fix-up novel, various parts of it appeared in Galaxy Magazine and Fantasy and Science Fiction between 1968 and 1972. It is probably his best known novel, but apparently not one instantly recognized as a masterwork. Gunn missed out on all awards and nominations save one for the Campbell award in 1973. There have been a whole bunch of editions of this book with different forewords, introductions and afterwords. The copy I’ve read is a 2004 edition which features an introduction by H. Paul Shuch, an American physicist heavily involved with SETI, a foreword by Thomas Pierson, founder of the SETI Institute, and and afterword by the late Freeman J. Dyson, British-American mathematician and physicist. I guess this book is still well loved in scientific circles.

In 2028, the SETI’s search for extraterrestrial life is still ongoing without ever having picked up a single signal that indicates intelligent life. Director Robert McDonald, a staunch believer in the project, is facing ever more difficulties keeping SETI funded. McDonald himself is beginning to wonder if the project is worth the personal sacrifices he has to make. Then, a signal is received that is unmistakably of alien origin. A broadcast is received from a the direction of the star Capella, 45 light years distant. It changes everything. The project, the world, our place in the universe. Humanity is about to enter into a conversation with a ninety year time lag.

The Owl Killers, by Karen Maitland

Today’s Month of Horrors review is from blogger and WWEnd member Valashain. This review originally appeared on his blog Val’s Random Comments, where he regularly reviews science fiction and fantasy books. The Owl Killers was a 2009 nominee for The Shirley Jackson Award.

The medieval period in Europe serves as an inspiration to many a fantasy novel. Apparently there is something very appealing to imagining oneself living in such an environment, so much so that our perception of the period has become more than a bit romanticized. In sharp contrast, history books tell us just how miserable and brutal life could be for a large part of the population. Historical fiction does not entirely escape the romanticizing of this period but quite a few novels attempt to paint a more realistic picture. Like Maitland’s previous book Company of Liars, The Owl Killers does not shy away form the harshness of life. Hunger, disease, natural disasters, oppressive taxation and unbridled religious madness, very little is spared the 14th century village the book depicts. It makes The Owl Killers in a very dark book. Fear is a main ingredient and the author makes sure the reader knows it.

GMRC Review: Dragonsdawn by Anne McCaffrey

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his ninth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his ninth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

As I’ve noted before, the Damon Knight memorial Grand Master Award is seriously short on female authors. Only four out of the twenty-eight winners are women. Since one of my objectives for this year is to read more work written by women I am going to try to read all four for this challenge. I read Forerunner by Andre Norton and The Wind’s Twelve Quarters by Ursula K. Le Guin earlier this year. Next up is Anne McCaffrey, who was honoured with this award in 2005. Picking a book was a bit of a problem. McCaffrey is best known for her Pern novels, of which I have read exactly one: Dragonflight, published in 1968. I didn’t like it very much. I’m sure it was sensational at the time but forty years on, it seemed like a pretty mediocre novel to me. An Australian friend of mine is a bit better acquainted with McCaffrey’s oeuvre and she suggested I try Dragonsdawn (1988). Chronologically it is the first of the Pern novels (there are a few shorter pieces in the same era or even set before the novel) but McCaffrey wrote it some twenty years after Dragonflight. I must say, the fact that she had a bunch of novels under her belt by this time shows in the writing.

As I’ve noted before, the Damon Knight memorial Grand Master Award is seriously short on female authors. Only four out of the twenty-eight winners are women. Since one of my objectives for this year is to read more work written by women I am going to try to read all four for this challenge. I read Forerunner by Andre Norton and The Wind’s Twelve Quarters by Ursula K. Le Guin earlier this year. Next up is Anne McCaffrey, who was honoured with this award in 2005. Picking a book was a bit of a problem. McCaffrey is best known for her Pern novels, of which I have read exactly one: Dragonflight, published in 1968. I didn’t like it very much. I’m sure it was sensational at the time but forty years on, it seemed like a pretty mediocre novel to me. An Australian friend of mine is a bit better acquainted with McCaffrey’s oeuvre and she suggested I try Dragonsdawn (1988). Chronologically it is the first of the Pern novels (there are a few shorter pieces in the same era or even set before the novel) but McCaffrey wrote it some twenty years after Dragonflight. I must say, the fact that she had a bunch of novels under her belt by this time shows in the writing.

After a long journey though interstellar space, three ships full of colonists arrive in the Rukbat system where they intend to colonize the third planet. When they bought into the expedition, they knew it would be a one way trip. The ships are nearly out of fuel, they will be cannibalized to provide the colony with materials. Pern, as the third planet is referred to, is a remote place, far away from the busy shipping lanes of the galaxy and has only been surveyed briefly. The planet has developed its own ecology but is without sentient life. There is every possibility to create an utopian society, away from the wars and conflicts of the more densely populated regions of space. The colony is developing rapidly with only minor squabbles along the way when the colonists become aware of a major threat to their existence. Threadfall. Their rapidly declining technological resources will not be enough to save them. Other, more radical options will have to be considered.

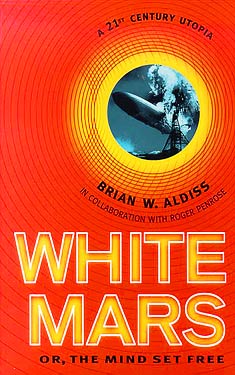

GMRC Review: White Mars by Brian Aldiss

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his eighth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his eighth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

While rereading Kim Stanley Robinson‘s Mars Trilogy, books I consider to be among the very best in science fiction, I came across various references to White Mars Or, The Mind Set Free by Brian W. Aldiss, written in collaboration with prominent physicists Roger Penrose. Robinson’s utopian vision of a terraformed Red Planet is not something everybody would see as ideal or even morally acceptable. In the Mars Trilogy Robinson pays a lot of attention to the discussion between what he calls the Reds, a faction opposed to terraforming the planet and convinced of its intrinsic value, and the Green faction who would exploit the planet and make it more hospitable to human life. Aldiss (and Penrose) wrote this novel as a reply to Robinson’s vision of utopia portrayed in his Mars novels. The debate about how to set up a utopian society on Mars is the single most important topic in this book. As a nod to his source of inspiration, Robinson even had a street named after him. As far as I can tell White Mars is out of print, I had a hard time tracking down a useful copy without resorting to the countless torrents out there. After having read it, I can’t say I am terribly surprised by the relative obscurity of this book. The philosophical argument may be sound, as a work of literature Robinson’s novels are far superior.

While rereading Kim Stanley Robinson‘s Mars Trilogy, books I consider to be among the very best in science fiction, I came across various references to White Mars Or, The Mind Set Free by Brian W. Aldiss, written in collaboration with prominent physicists Roger Penrose. Robinson’s utopian vision of a terraformed Red Planet is not something everybody would see as ideal or even morally acceptable. In the Mars Trilogy Robinson pays a lot of attention to the discussion between what he calls the Reds, a faction opposed to terraforming the planet and convinced of its intrinsic value, and the Green faction who would exploit the planet and make it more hospitable to human life. Aldiss (and Penrose) wrote this novel as a reply to Robinson’s vision of utopia portrayed in his Mars novels. The debate about how to set up a utopian society on Mars is the single most important topic in this book. As a nod to his source of inspiration, Robinson even had a street named after him. As far as I can tell White Mars is out of print, I had a hard time tracking down a useful copy without resorting to the countless torrents out there. After having read it, I can’t say I am terribly surprised by the relative obscurity of this book. The philosophical argument may be sound, as a work of literature Robinson’s novels are far superior.

Since this novel is a reply to Robinson’s work I find it very difficult not to see it in the light of the Mars Trilogy. In fact, when I first heard about the novel I questioned the wisdom of trying to cover ground Robinson had already so thoroughly explored. No matter how unfair it may be to compare books of different authors to each other, this novel practically begs for it. I’m not sure how much sense this review will make if you have not read Robinson’s novels. You have been warned.

GMRC Review: Beyond the Blue Event Horizon by Frederik Pohl

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his seventh for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his seventh for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Beyond the Blue Event Horizon is the second book in Frederik Pohl‘s Heechee Saga, a series that started out with the 1972 novella The Merchants of Venus. This novella was reprinted in Platinum Pohl among other collections. The first Heechee novel, Gateway (1976), is one of his best regarded solo novels and won him a whole shelf full of awards. I guess it is not surprising that after that kind of success, a sequel has a hard time living up to expectations. I’ve heard a lot of people say this is one of those series you should only read the first book of. Pohl went on to write three more books and a bunch of short fiction, none of which I have read, but personally I didn’t think Beyond the Blue Event Horizon a bad book. It is very different from Gateway though, that has to be said.

After successfully facing his successes and failures at Gateway, Robinette Broadhead is now living the life of a very rich man. He has married and has diverse interests in various profitable businesses as well as close ties with the Gateway corporation and even quite a bit of political influence. In other words, he has it made. Still, there is the nagging feeling of guilt that the woman who is the love of his life is stuck in a singularity. In business problems arise as well when an expedition to a distant Heechee installation, which Robinette hopes will help combat the chronic food shortages on Earth, meets with unexpected problems. It takes 25 days for instructions to reach the explorers, and as the situation in the outer solar system gets more and more out of control, Robinette’s problems increase. Desperate action is needed.

One of the most striking differences between Gateway and Beyond the Blue Event Horizon is that Pohl employs a lot of different points of view in the second volume. In fact. Robinette doesn’t even show up until the fourth chapter, some 50 pages into the novel. A lot of the major players in the novel get a point of view, as well as some of the machine entities, but there are quite a few of them, so we only get to scratch the surface of most of these characters. Where Pohl was very concerned with the psychology of Robinette in the first novel, the plot is obviously more important in the second. That is not to say that Robinette’s internal struggle is not an important part of the story, he is still this petty, selfish but basically decent person we met in Gateway, but Pohl leans quite heavily on events in the previous novel to convey this to the reader.

The Heechee on the other hand, although still very absent, are much more important to the story. The artifact being explored is clearly one of theirs but has been circling the sun since before humanity’s ancestors learnt to use tools. It has a history of its own and that history includes other intelligences as well. Pohl reveals that history through these many points of view, gradually revealing a new part of the mystery with each chapter. It is this revealing that may put off some readers. In Gateway, the Heechee are a mystery. With only their incomprehensible artifacts and structures around, very little was actually known for sure about them. It made the story unpredictable in a way. With a Heechee artifact around, you never know what might happen. The increased understanding in Beyond the Blue Event Horizon changes that. Personally I don’t think you can reasonably expect the mystery to stay intact for several books, there has to be at least some progress to keep the story moving, but some readers will no doubt prefer their own questions, answers and guesses over those of Pohl.

Pohl’s answers to the riddle the Heechee and their seemingly impossible technology pose, involve a lot of guesswork and quite a bit of cosmology and physics. I must admit some of it was right over my head. Still trying to wrap my head around Mach’s principle for instance, an idea that was apparently one of the inspirations to Einstein’s general theory of relativity. It also contains a number of references to Stephen Hawking’s work on black holes. Where electronic shrink Siegfried is Robinette’s discussion partner of choice in the first book, in this one his science program, aptly named Albert, takes over. It must be said, Albert is very good at explaining his guesses, which, especially towards the end of the novel, become more and more important to the plot. One would expect a program modelled on one of the greatest physicists of all time to do a little less guessing, but Robinette often orders him to do so anyway. Some of these guesses are obviously a set up for the next novel. It appears fairly obvious what Robinette’s next project will be. This novel, after all, does not solve the issue that is the basis of his ever present guilt.

Pohl’s works often have a satirical undertone. Many of his works criticize the excesses of capitalism for instance, or are fairly cynical about the political influence and proper healthcare money can buy. Robinette is not adverse to using his wealth to get things done his way for instance. It is not quite as apparent in this book however. The most notable thing about this novel is that it is drenched in fear. The fear of meeting the unexpected in space, where there is no retreat and very little margin for error. More than a few science fiction novels feature fear, suspicion and paranoia. Especially the so called big dumb object stories, of which Gateway could be considered a variation, usually contain it in a general measure. I guess it is not as claustrophobic as Gateway, but the knowledge that aliens are near weighs on the characters. Due to the number of point of view characters, it is not as oppressive as in the previous novel, but it is almost always present in the background as each of these characters experiences their own personal flavour of fear.

Pohl’s works often have a satirical undertone. Many of his works criticize the excesses of capitalism for instance, or are fairly cynical about the political influence and proper healthcare money can buy. Robinette is not adverse to using his wealth to get things done his way for instance. It is not quite as apparent in this book however. The most notable thing about this novel is that it is drenched in fear. The fear of meeting the unexpected in space, where there is no retreat and very little margin for error. More than a few science fiction novels feature fear, suspicion and paranoia. Especially the so called big dumb object stories, of which Gateway could be considered a variation, usually contain it in a general measure. I guess it is not as claustrophobic as Gateway, but the knowledge that aliens are near weighs on the characters. Due to the number of point of view characters, it is not as oppressive as in the previous novel, but it is almost always present in the background as each of these characters experiences their own personal flavour of fear.

There is one element in this novel that I absolutely didn’t like, and that is the way Robinette’s wife is portrayed. She is practically perfect in every way, knowing what is wrong with him before he knows himself and allowing him to go after the love of his life, who according to physics should be out of reach forever. Events in Gateway are more than enough reason to feel guilty but Robinette’s treatment of his wife certainly adds to the problem. Siegfried’s work doesn’t appear to be done. The story is a bit open ended on this point. It looks like Pohl will get back to it in the third volume.

I guess you could say Pohl took a bit more conventional approach in writing Beyond the Blue Event Horizon. It makes the book less groundbreaking than Gateway was and probably is part of the reason why it didn’t win any of the awards it was nominated for. The scope of it is obviously much wider too, and the many switches in point of view makes it appear a bit less structured than its predecessor. If you view the story as the unveiling of (part of) a mystery, it makes more than enough sense to me. In the end I guess I agree with many of the critics that it is not quite as good a novel as Gateway was. I also think it would have been nice if it had been a little more self contained; if it were fantasy I’d say this book suffered from the middle book syndrome a bit. That being said, it is a good science fiction novel in the classic sense. Plenty of hard science, scientific speculation and a much larger scope than the first book in the series offer their own attractions. I guess it depends on what you want out of a novel but I thought it was an enjoyable read.

GMRC Review: The Wind’s Twelve Quarters by Ursula K. Le Guin

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his sixth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his sixth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

The Wind’s Twelve Quarters is Ursula K. Le Guin‘s first collection of short fiction and was published in 1975. Quite unusual for a single author short science fiction collection, it is still in print decades after it has been first published. It is generally regarded as the strongest of her collections of short fiction. Not having read the others, I don’t have an opinion on that but I did think The Wind’s Twelve Quarters is a bit of a mixed bag. It contains a total of seventeen stories, presented more or less in the order they were published and cover the period between her first publication in 1962 and 1974, by which time she had published some of her best know and most critically acclaimed novels. Le Guin chose this order so the reader could experience her growth as an author. In that respect the collection certainly succeeds. The later stories are much stronger than the earlier ones. Most of the stories have a short introduction by Le Guin about the inspiration for the story and the editorial changes compared to the original magazine publications. A fair number of stories in the collection are what Le Guin calls psychomyths. These stories are hard to pin down but they are independent of setting and often have a surreal quality to them. Le Guin herself puts it like this:

…more or less surrealistic tales, which share with fantasy the quality of taking place outside any history, outside of time, in that region of the living mind which – without invoking any consideration of immortality – seems to be without spatial or temporal limits at all.

Le Guin on psychomyths – Foreword

Most of the stories that are not tied to her novels seem to fall into this category. Quite a few of the stories are linked to her novels though. There are Earthsea stories in this collection as well as stories set in the Hainish universe and even a story tied to her novel The Dispossessed (1974). The opening story, "Selmy’s Necklace" (1964), is essentially the prologue of Le Guin’s first novel, Roccanon’s World (1966). It is set in her Hainish future history and in some ways, reminded me a lot of some of Poul Anderson‘s Technic Civilization stories. It is seen mostly form the point of view of a member of a less technically advanced race trying to retrieve an heirloom that that was lost decades ago. She doesn’t properly comprehend the consequences of her request to be allowed to visit the aliens but to the reader the tragedy that is unfolding is quite clear. A science fiction story written in language that is more often found in fantasy. This story clearly shows why Le Guin usually doesn’t make too rigorous a distinction between the two.

The second story is "April in Paris" (1962) is the earliest story in the collection and Le Guin’s first sale. I can’t say I liked it much. I guess you could say it is a time travel story. I thought it was pretty predictable with more than a bit wish fulfilment in it. Le Guin then moves on to a story that is also a bit predictable but conceptually more interesting. "The Masters" (1963) deals with a man who is brought up in a very strict guild like environment where things have always been done a certain way and where deviating from this way, or trying to improve upon it, is heresy. He can’t resist the lure of progress though. There is another story that is thematically related to this one in the collection. "The Masters" is very dark, full of despair. Stylistically probably not the strongest piece but certainly an interesting one. "The Darkness Box" (1963), like "The Masters" is a piece that can be considered a fantasy or perhaps an early psychomyth. It’s a story with a sense of inevitably about it, of pointless repetition. Not a story that makes one feel happy although one of the characters sees things differently.

"The Word of Unbinding" and "The Rule of Names" (both 1964) are Le Guin’s first Earthsea stories. I haven’t read any of the Earthsea novels so putting them into the perspective of the whole series is going to be a bit difficult. I think they lay the groundwork for the system of magic found in the Earthsea novels. A system that appears to be quite sophisticated judging from these few pages. The stories are uncut fantasy, the only ones in this collection. I will have to read one of the Earthsea novels to be sure but I think I prefer Le Guin’s science fiction. Still, Earthsea is on the to read list.

"Winter’s King" (1969) is another story tied to one of Le Guin’s novels. It is set on the same planet as The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), a novel in the Hainish cycle that is also on my to read list. The version in this collection has been changed to fit the novel more closely and features the wintry world of Gethen. Le Guin plays with titles and particular pronouns to underline the androgyny or the inhabitants. The story itself is one of mind control and a King struggling to do what is best for the kingdom. It certainly makes me curious about the novel. Gethen seems like an intriguing place and the way gender appears to play no role in society opens up all kinds of interesting possibilities. Something that struck me about this story is how, like in "Selmy’s Necklace", Le Guin presents a technologically less advanced society in a science fiction story. Some readers would say there is a hint of fantasy in this story.

"The Good Trip" (1970) is a story that is probably contemporary. As the title suggests it is about drug use among other things. The trip makes it quite a strange story full of weird cognitive leaps and odd situations. Le Guin didn’t seem to be opposed to people experimenting with LSD at the time, which was no doubt frowned upon. She does mention in the introduction that she feels that "people who expand their consciousness by living instead of taking chemicals usually come back with much more interesting reports of where they’ve been." Now there is a bit of wisdom for you.

"Nine Lives" (1969) is one of the longer pieces of the collection and is a classic science fiction story. One that explores the possibilities of a new technology, in this case cloning. Le Guin studies the bond between genetically identical individuals, who shared most of their formative years and education and have been brought up to function as a team. The idea is disturbing on many levels. These people are a product, designed to outperform ordinary humans but also to be so self sufficient that without each other, they’d be lost. In a way, it is a barrier to get ideas of their own, which of course Le Guin can’t help but challenge. As with the best science fiction stories, this one contains plenty of food for thought.

The next story, "Things" (1970) is another psychomyth. I guess you could say it is about a man who has to take the last leap. It is beautifully written but personally I think it doesn’t quite take that many words to convey the message. Le Guin creates quite an elaborate setting. One which could have been explored in more detail, but Le Guin takes the story in another direction and much of the setting ends up being only marginally relevant to the story. This one was a miss for me. The collection continues with "A Trip to the Head" (also 1970). All I have to say about this, is that it went right over my head. I guess Le Guin’s writing is too intelligent for me sometimes.

What follows is the story with the most beautiful title in the collection. "Vaster Than Empires and More Slow" (1970) is a story in the Hainish Cycle, covering the lonely journey of a ship of explorers. Given the nature space travel at relativistic speeds, they give up everything they’ve known to go on this journey. Something not everybody is willing to do. The crew consists of misfits, people who have nothing to loose and the occasional completely dysfunctional character. A recipe for trouble and indeed, the first planet they survey, puts them to the test. This again is pretty straight forward science fiction, with perhaps a touch of horror. Or suspense if you will. I liked it a lot but it is not outstanding.

What follows is the story with the most beautiful title in the collection. "Vaster Than Empires and More Slow" (1970) is a story in the Hainish Cycle, covering the lonely journey of a ship of explorers. Given the nature space travel at relativistic speeds, they give up everything they’ve known to go on this journey. Something not everybody is willing to do. The crew consists of misfits, people who have nothing to loose and the occasional completely dysfunctional character. A recipe for trouble and indeed, the first planet they survey, puts them to the test. This again is pretty straight forward science fiction, with perhaps a touch of horror. Or suspense if you will. I liked it a lot but it is not outstanding.

"The Stars Below" (1973) explores in a bit more depth, one of the themes we also encountered in "The Masters". Scientific curiosity clashes with custom or religion and ends in violence. Where "The Masters" deals with the event itself, this story shows us the aftermath. An astronomer who’s instruments were destroyed hiding in an abandoned mine from his tormentors. It is a tragedy, even when he finds something to replace his interest in the stars. A moving story. I thought it was one of the better ones in the collection.

The collection continues with another science fiction story that is unrelated to a novel. "The Fields of Vision" (1973) about a group of astronauts who discover a strange city, for lack of a better word, on Mars that messes with their perceptions. One of them does not survive the trip back, the other two have lasting problems with their sense of hearing and sight. Their adjustment to this situation takes very different routes. I liked how Le Guin linked our perceptions with religious experiences in this story, and how much our brain relies on what our senses tell us. Most people trust what their senses tell them without question. In this story the characters know the input they are receiving is somehow changed. The author depicts this as quite a scary experience.

The next story is a very short, to the point science fiction story in which the main character is a tree. "Direction of the Road" (1974) is a highlight in the collection for me, a brilliant little story about relativity. It would spoil the story to say anything about the plot but it is such a strange reversal of how we think the world works, that I just had to read this story again right after I finished it. If I had to pick a favourite, this story might well be it.

For "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" (1974), Le Guin received a Hugo Award as well as a nomination for the Locus Award. It is another psychomyth, perhaps the one closest to the loose definition Le Guin put in the foreword to this collection. The story is very abstract in a way, no details on the setting (the author basically tells us to imagine our own), or characters are given. The story revolves around a scapegoat, one who is necessary to keep the rest of society happy. Once again a disturbing thought. One, as the story points out, not everybody can live with.

The final story of the collection is also one of the strongest ones. "The Day Before the Revolution" (1974) won a Nebula and a Locus award and was nominated for a Hugo. The story is tied to the novel The Dispossessed, a novel that I still consider to be one of the best in science fiction. It’s main character is Odo, who is a historical figure in the novel, the inspiration for the anarchistic society on Anarres. She may be honoured after her death but the life of a revolutionary is not easy. The story shows us an ageing Odo, full of grief and a premonition of death. The subtitle of The Dispossessed is An Ambiguous Utopia and this story is another expression of it. Odo achieved a lot but at a high price. I love the final paragraph of this story. As far as I am concerned, it should have won that Hugo too.

The Wind’s Twelve Quarters ends on a high, that is for sure. Some of the stories in this collection are no doubt among the best Le Guin as produced. All things considered, it isn’t one of those very rare collections that manage a consistently high quality though. It is a collection that shows Le Guin’s style, themes and development as a writer however. With links to her most important works and some award winning stories, perhaps it is not so strange this collection has been in print for more than three decades. I would not recommend someone with an interest in Le Guin’s work to start here, it is probably better to have read a few novels first, but for the real fan it is definitely a must read.

GMRC Review: I, Robot by Isaac Asimov

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his fifth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his fifth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

For my fifth Grand Master reading challenge, this project may well be the only one at Random Comments that runs on schedule, I decided to read something by Isaac Asimov. Several of his novels feature prominently on all kinds of recommended reading lists and he is certainly one of the genre’s towering figures. I read his Foundation novels (the original trilogy) a while ago and I can’t say I was overly impressed. Asimov didn’t lack ideas but his prose is barely serviceable and he has the tendency to explain everything in great detail to his readers. Perhaps I should have picked something from later in his career but I, Robot (1950) is such an iconic work in the genre that I felt I should give it a go. Much to my surprise, I liked this book better than the Foundation novels. Not that the flaws in Asimov’s writing are absent in this novel, but the quality of the stories is more consistent and on the whole, I though them more entertaining as well.

I, Robot has been described as a fix-up novel or a short fiction collection. I think of it as the former but it is certainly true that most of the text appeared in the shape of various short stories between 1940 and 1950 in a Super Science Fiction Stories and of course John W. Campbell‘s Astounding Science Fiction, to whom the book is dedicated. Asimov has connected the stories with bits of interviews with Dr. Susan Calvin, a robotpsychologist working for U.S. Robots and Mechanical Men, Inc., as she is looking back on her long career in the field. She is not always the main character, or even a character, but she does provide just enough context to put the stories into a general future history. Asimov does this in his usual efficient way, not wasting a word more on it than absolutely necessary. I understand Asimov changed some of the details in the stories to make them more consistent. He is certainly making the most of repackaging these short stories with minimal effort here.

Being written in the 1940s, most or the novel is pretty badly dated and some of Asimov’s depictions of the future will seem decidedly strange to new readers. We have caught up with the start of the series now. I, Robot starts in 1996, with the story Robbie (1940), about a primitive robot and playmate of the eight year old Gloria. The girl treats the robot like she would a human friend and this makes her mother uneasy. Robbie wil have to go. Asimov uses the story to outline the resistance against artificial intelligence, the fear of superior robots replacing human beings. First in the work space and later completely. It is an introduction to his famous three laws of robotics, which he will name in the second story Runaround (1942).

"We have: One, a robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm."

"Right!"

"Two," continued Powell, "a robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law."

"Right!"

"And three, a robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws."

— Powell and Donovan discussing the Three Laws of Robotics – Runaround

Runaround, set in 2015, introduces the field testers Powell and Donovan and is a story in which Asimov examines the conflicts that may arise from these three laws. The laws are the kind of logic that Asimov seemed to have liked, simple, elegantly formulated and its intent easily understood. He was smart enough to see they are by no means flawless though. Most of the stories contain situations in which some conflict between these laws makes the robots behave unexpectedly or cause them to be caught in a loop, often jeopardizing the project they are working on or the lives of the unfortunate humans in their company. In Runaround it happens in the supremely hostile environment on Mercury, which shows just how little we knew about conditions on the planet in 1940. It gives Asimov plenty of room to speculate though.

Some six months after events in Runaround Donovan encounter a different sort of problem. In Reason (1941), which I consider to be one of the strongest stories, Asimov takes a more philosophical tone when our field testers are stuck with a robot who will not accept the (in its opinion) contrived and unnecessarily complicated explanation for its existence. A case of Occam’s razor gone blunt I suppose. This story contains the most memorable quote in the book if you appreciate sarcasm.

"I have spent these last two days in concentrated introspection", said Cutie, "and the results have been most interesting. I began at the one sure assumption I felt permitted to make. I, myself exist, because I think…"

Powell groaned, "Oh Jupiter, a robot Decartes!"

— QT-1 discussing its own existence.

Cutie retreats from reality along the same lines as a human being might do in the end by resorting to religion, shutting out the need for an explanation. It is one of several instances where robotpsychology runs parallel to human psychology. Something even Susan Calvin reluctantly admits later on in the book.

In Catch That Rabit (1944) robot behaviour shows some parallels to buggy software as well. It sees our field testers use drastic measures to get the robot back under control. Asimov spends a lot of the later part of the story lecturing (disguised as a conversation between Powell and Donovan). I can’t say I particularly liked it. Liar! (1941) is more interesting. Set in 2121, it deals with a robot that can read minds. The conflict arises when it receives one set of instructions verbally, that don’t correspond with the real desires of the person giving the instructions. Calvin’s behaviour in this story will no doubt make some readers groan but the concept is a strong one.

By the time of Little Lost Robot (1947), robots have become quite advanced and exploration of the solar system is well under way. In 2029, one such space program employs robots with a slightly altered set of robotic laws, enabling them to ignore a human being putting themselves in danger. If the mere existence of such a robot was to become public knowledge on earth, the political consequences would be dire. When one of the robots is lost, the people who run the project are in deep trouble. Calvin is called upon to find it. The three laws of robotics can be quite a restriction I suppose, so the temptation to do away with them is clear. Asimov presents a perfectly reasonable argument for doing so in this story. It might have worked better if there had been more of an element of danger in the story though. The missing robot is still unable to actively do harm. Personally I wouldn’t have been particularly worried to have it around.

By the time of Little Lost Robot (1947), robots have become quite advanced and exploration of the solar system is well under way. In 2029, one such space program employs robots with a slightly altered set of robotic laws, enabling them to ignore a human being putting themselves in danger. If the mere existence of such a robot was to become public knowledge on earth, the political consequences would be dire. When one of the robots is lost, the people who run the project are in deep trouble. Calvin is called upon to find it. The three laws of robotics can be quite a restriction I suppose, so the temptation to do away with them is clear. Asimov presents a perfectly reasonable argument for doing so in this story. It might have worked better if there had been more of an element of danger in the story though. The missing robot is still unable to actively do harm. Personally I wouldn’t have been particularly worried to have it around.

In Escape! (1945), positronic brains have become so advanced they are capable of calculations comparable of those of a super computer. The Brain, as this robot is called, is set to the task of creating the means for interstellar travel, a problem that has already cracked a competing robot. Calvin is aware that there is a conflict with the three laws but doesn’t know where. The company tries to avoid the problem by feeding The Brain the information is small sections. It features a lot of irrational behaviour on the Brain’s part. I’m not particularly fond of this story but as usual, Asimov’s rationale is perfectly logical.

The book then moves on to 2032, a year that poses a completely different challenge to Susan. A Turing with a twist. In Evidence (1946), Stephen Byerley is a brilliant district attorney running for mayor, when one of his opponents accuses him of being a robot. How do you prove someone is a robot when the subject is not cooperating and very aware of his rights? Written during the aftermath of the second world war, it is easy to see what Asimov (of Russian Jewish descent himself) was aiming at. It is the most politically charged story in the book, with a lot of it focussing on the suspicion and outright hatred of robots despite the fact they are incapable of harming a human being. Where Asimov usually explains the entire plot to the reader in detail, this story is certainly food for thought.

Interestingly enough I, Robot then goes to show us some suspicion of robots might actually be warranted. In The Evitable Conflict (1950), set in 2052, Calvin has realized that robots rule the world. They are responsible for the allocation of goods and services and the division of labour of the entire planet, which by that time is divided into four super states. Calvin is called upon to explain apparent imperfections in the solution the robots provide. These turn out to have a perfectly reasonable explanation in line with the three laws of course. This story has aged very badly, Asimov’s future, at this point in time, seems positively silly, although from his perspective it might not have been entirely impossible. It was not my favourite part of the book though. Partly because of Asimov’s tendency to explain everything and partly because of the fact that the plot is mostly a guided tour though planetary government in 2052.

With I, Robot Asimov lays the foundation of what would become one of the three main series in his career as a science fiction writer. He is not technically a good writer (at this point in his career at least) but back in the days where science fiction was very much seen as the literature of ideas, you probably couldn’t do much better than Asimov. He had ideas and was not afraid to explain them at length. For the modern reader a lot of I, Robot is dated but with lasting contributions to the genre such as the three laws of robotics and the positronic brain, it is one of the novels that shaped the genre. One of the thoughts that kept returning while reading this novel is just how many things Asimov discussed that were in the experimental stage at the time, or didn’t exist at all. All things considered, I think it deserves at least some of the praise that is heaped on it.

GMRC Review: Dying Inside by Robert Silverberg

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his third for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his third for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Robert Silverberg must be one of the most prolific authors in Science Fiction. I’m not sure if there is such a thing as a complete bibliography on the web but the ones I’ve seen rival those of Isaac Asimov. Since the 1950s Silverberg has written science fiction, fantasy, soft-pornography, non-fiction, countless short stories and edited shelves of anthologies. A quick search turns up at least two dozen pseudonyms. Not all of his output is highly regarded. Especially the early works, a period during which Silverberg was basically writing as fast as he could and selling his material to pulp magazines, are considered of lesser quality. Dying Inside (1972) was written during a later period in his career, lasting from the late 1960s till his first retirement in 1975. During those years Silverberg produced some his most celebrated science fiction novels. Works in which he takes a more literary approach than earlier in his career.

David Selig is a middle aged man living in New York. When we first meet him, he is making a living selling term papers to Columbia University students, a place where he once studied himself. David is not a happy man, for the last few years he’s been feeling his talent to read people’s minds fading. It is a talent that brought him an unhappy childhood as well as immense grief and countless problems in his personal life over the years, but also one that defines him as a person. Now that it is slipping away from him, he feels he is dying inside.

For a Science Fiction novel, the story contains very few speculative elements. Selig is a powerful telepath but that is just about the only thing science fictional to it. The novel is a character study of Selig, quite introspective and entirely focused on his struggles with his talent and accepting his loss of it. The author plays with memories and flashbacks in the novel, eventually covering most of Selig’s life. Maybe this lack of action and the less plot driven character of the novel are the reason why it didn’t win any of the awards it was nominated for. It was nominated for the Nebula, Hugo and Locus awards, all three of which ended up being won by Isaac Asimov’s The Gods Themselves. I haven’t read that book, but from the description I’d say it is a bit more in line with what readers would have expected from a science fiction novel in the 1970s.

Selig is obsessed with literature, poetry, plays, classical music and philosophy and Silverberg stuffs in a lot of references to famous works of art in the story. I’ve always found it interesting that a science fiction novel is much more likely to contain such references to the classics of literature than the other way around. Silverberg included one of Selig’s papers on the works of Franz Kafka for instance. Which is not only a reference to one of his literary influences but also an example of the different styles of writing we find in the novel. The author also includes letters and has Selig talk to himself in the second person in an attempt to distance himself from some of his more shameful acts. The shifts between different phases of Selig’s life, in combination with the different styles of narrative, help keep things interesting.

At several points in the novel I wondered how much of the story is autobiographical. There are some similarities between Selig and Silverberg. Both from Brooklyn, both studied at Columbia, both with an intense interest in literature. I haven’t come across any biographies that mention Silverberg being Jewish but, given his name, it is certainly possible. A writer peering into the head of his characters (or his own head if you support the idea that all characters are some aspect of the author) is not that different from reading the mind of the people around you. Selig seem to make the link between the loss of his talent and his diminishing sexual prowess. More than one critic has pointed out the parallel between the loss of Selig’s talent and Silverberg’s loss of joy in the creative process. Something that apparently appears in different forms in other novels from this period and may have contributed to his first retirement. It sounds plausible to me but given my unfamiliarity with Silverberg’s work I have no idea how accurate it is.

Selig is a very depressing character during most of the book. His life is an unhappy one. He thinks of his talent as a curse most of the time although loosing it upsets him greatly as well. Reading the minds of others is often painful to him. Their true opinion and motives are completely clear to him and it often includes things he’d rather not hear about himself. He finds it almost impossible to start a relationship with a women when he can read her mind and the few times that he does try, it inevitably ends in disaster. One of he most telling examples of Selig’s problems with his talent is when he takes a peak in the mind of the woman he is making love to and finds she can spare not a single thought about him when she is about to climax. Not entirely unexpected perhaps, but it is a devastating experience nonetheless. It is the leitmotiv of his life I guess, people don’t really want to know the truth of what other people think of them and Selig shows us why. They shade the truth, hedge or outright lie in order to function socially. I do wonder if the emphasis Selig puts on the ugly things he finds in the minds of those around him isn’t a bit overdone. Do doubts, fears, distaste and anger really outweigh the positive things that must be present in a person as well? His reaction to knowing what people think may say more about Selig himself than the people he reads.

I guess it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Selig’s talent can be used for personal gain. Selig does so himself in various, usually petty ways but not until he meets Tom Nyquist does he realize the full extend of what is possible. Nyquist is the only other character we meet that has David’s talent and he is quite unapologetic about it. He makes lots of easy money on Wallstreet with inside trading and is not adverse to using his talent to manipulate people. Selig is amazed and repulsed by his style of living, Nyquist’s life is one of luxury but Selig feels it is empty and ends up disgusted with him. Embracing his talent in that way makes Nyquist a lot more comfortable with himself than Selig is however, and to Selig, Nyquist can’t lie about that.

I guess it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Selig’s talent can be used for personal gain. Selig does so himself in various, usually petty ways but not until he meets Tom Nyquist does he realize the full extend of what is possible. Nyquist is the only other character we meet that has David’s talent and he is quite unapologetic about it. He makes lots of easy money on Wallstreet with inside trading and is not adverse to using his talent to manipulate people. Selig is amazed and repulsed by his style of living, Nyquist’s life is one of luxury but Selig feels it is empty and ends up disgusted with him. Embracing his talent in that way makes Nyquist a lot more comfortable with himself than Selig is however, and to Selig, Nyquist can’t lie about that.

Another striking thing about Selig’s view on the world is how much it revolves around sex. It motivates our actions to a much greater extend than many people would be comfortable admitting but since Selig tends to see right through others, it is very much exposed to him. Finding partners is rarely a problem for him since he knows for certain who is available and interested. Which of course takes something of the thrill of the chase away. Where sexual attraction or desires are mostly kept hidden for others, something not discussed openly or at best considered very private, it is completely exposed to Selig from a young age. It gives him a unique perspective on these matters and Silverberg is not afraid to expose his readers to it. He succeeds in showing the reader why this is as uncomfortable to Selig as it is to his surrounding.

I can see why this is a notable book among it’s contemporaries. Silverberg approaches the novel in a way you don’t see a lot in science fiction novels. It is a pretty dark and introspective book. I’m not sure everybody will appreciate the ending but I thought it was fitting. Dying Inside is a book that can make the reader uncomfortable by laying bare the innermost thoughts and feelings of the characters. It usually isn’t pretty, but like it or not, most of us will recognize a lot in what Selig is exposed to. I can see why this novel is one of the more highly regarded novels of the period. Some Science Fiction novels age badly. In some ways this is a novel of its time but certainly highly readable today. I’m going to have to read some more Silverberg.

Full Details

Full Details