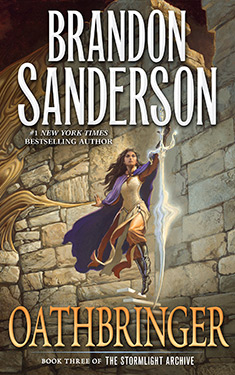

Guest Post: Oathbringer Review

This guest post by Craig Hanks originally appeared at TheLegendariumPodcast.com and is reprinted here with permission. The Legendarium Podcast is a must for any Sanderson fan — these guys are the experts — and they cover many other epic fantasy staples including Lord of the Rings, Wheel of Time, and Shannara. You can subscribe to The Legendarium on iTunes.

A note on spoilers. In this review, I’m not going to spoil any major reveals. But a few general plot points are fair game here. So if you’re hoping to go into your reading of Oathbringer 100% fresh (not a bad call, since impeccable story structure and Roshar-shattering reveals are Sanderson hallmarks), turn back now. If you’re just looking for a little pre-game commentary, though, then read on.

“Your words are not that special, Brandon Sanderson.”

So said my wife after I congratulated myself on finishing one-third — 400 pages — of Oathbringer, the third of Sanderson’s mammoth Stormlight Archive series. Even for someone of my fantasy-oriented literary proclivities, this book is a monster. Ten-point type scrunched between barely-there margins, filling 1,250 pages? To the uninitiated, this appears as an act of extreme hubris. I assure you it is not.

It’s not hubris but deserved confidence that has driven Sanderson to write over a million words across three volumes of The Stormlight Archive so far. It’s the confidence of someone who is in full command of his prose and, more importantly, his worldbuilding. His words are great, but it’s his worlds that command attention. More on that in a bit; let’s talk Oathbringer specifically for a moment.

Listen to the spoiler-free review episode here:

The story still focuses on our three main characters: Kaladin, Shallan, and Dalinar. Where The Way of Kings revealed Kaladin’s back story and Words of Radiance did the same for Shallan, Oathbringer belongs to Dalinar. The title in this case refers not only to a book-within-the-book, as previously, but also to Dalinar’s mystical sword, or shardblade. Flashbacks show us Dalinar in his prime, wielding Oathbringer to devastating effect across the kingdom he is working to unite by force.

But the most impactful portions of the flashbacks are reserved for Dalinar’s relationship with his wife, memories of whom were apparently so painful that Dalinar had them magically excised from his mind. Learning what drove Dalinar to such drastic action makes for some of the most gut-wrenching scenes in Sanderson’s entire œuvre.

While the book focuses its flashbacks on Dalinar, fans of our other heroes need not worry; we spend plenty of time with both Kaladin and Shallan. Kaladin spends a good portion of Oathbringer learning that fulfilling his Windrunner oaths (“I will protect those who cannot protect themselves” / “I will protect even those I hate, so long as it is right”) requires actions that are not always easily justified.

Meanwhile, Shallan is faced with the same dilemma as Vin, the heroine of the Mistborn trilogy: she must decide which of her personae is the true one. The more literal nature of Shallan’s journey toward self-understanding is a result of the magic systems peculiar to Roshar and Shallan in particular.

Meanwhile, Shallan is faced with the same dilemma as Vin, the heroine of the Mistborn trilogy: she must decide which of her personae is the true one. The more literal nature of Shallan’s journey toward self-understanding is a result of the magic systems peculiar to Roshar and Shallan in particular.

Oh, and praise the Stormfather, the love triangle between Shallan, Kaladin, and Dalinar’s son Adolin that started in book two is resolved here in a way that is at once unexpected, sensible, and satisfying. Which is for the best, since the series at large could easily have been bogged down by a bunch of unnecessary — and surely angsty — YA-style emotional handwringing.

Time must be taken here — because damned if plenty of time wasn’t taken in the first half of the book — to mention secondary and tertiary characters, of which there are legion. Fan favorites are either completely absent (Eshonai) or cruelly underused (Rock, Lopen), while others are unexpectedly given substantial page counts (Teft, Moash). Depending on your appetites, this will either be a boon or a curse. I’m still undecided.

Ultimately though, Oathbringer, while clocking in at an eye-popping 391,840 words, manages to be the tightest of the three Stormlight books in terms of character scope, especially in the last half. As with The Way of Kings, there comes a tipping point somewhere around halfway through the book where the setups beget payoffs, which come faster and faster until the final pages. If you’d asked me at page 500 whether Oathbringer is a page-turner, I’d have said no. By page 800, though, it was a firm yes.

It’s not all roses, of course. As I’ve alluded to a few times already, this book is just plain long. While many high fantasy aficionados are ready and willing to dive into 1,000+ pages, such hefty word counts make The Stormlight Archives difficult to recommend to newcomers. If it’s true — as many Sanderson fans say — that this is his best series to date, then it’s a shame that it’s so difficult to recommend to anyone who isn’t yet on the Brandon train. Entry-level material this is not.

It’s not all roses, of course. As I’ve alluded to a few times already, this book is just plain long. While many high fantasy aficionados are ready and willing to dive into 1,000+ pages, such hefty word counts make The Stormlight Archives difficult to recommend to newcomers. If it’s true — as many Sanderson fans say — that this is his best series to date, then it’s a shame that it’s so difficult to recommend to anyone who isn’t yet on the Brandon train. Entry-level material this is not.

Another barrier to entry is Oathbringer’s dependency on Sanderson’s other work. To fully appreciate the characters and events of this book, it’s necessary not only to have read, but to remember fairly well several of his other “cosmere” books, especially Warbreaker, the Mistborn series, and Elantris.

Thankfully, these crossover moments are written in such a way that you won’t be slowed too much in your reading if you’re not familiar with these other books. But if you’re not up to speed with those stories, then you’ll likely be scratching your head at the end of Oathbringer, trying to figure out why certain characters and objects were so prominent. To a newcomer to Sanderson’s cosmere, this stuff will feel like so much bloat in an already massive book.

Back to those possibly-not-that-special words. There’s a tendency among Sanderson’s detractors, and even those who simply prefer other authors, to point to his prose style as lacking in some respect. The most common complaint I hear is something along the lines of, “It’s just so … utilitarian.”

But this is precisely what I, and millions of others, enjoy. And Sanderson’s prosaic prowess is on full display in Oathbringer. “In the best prose,” as Arthur Clutton-Brock put it in his essay The Cardinal Virtue of Prose, “we are so led on as we read, that we do not stop to applaud the writer, nor do we stop to question him.” Indeed, rarely does Sanderson puncture the fourth wall of the narrative with a poetic flourish, drawing attention to himself rather than the story at hand. His discipline helps to make this a story in which you can — and should, and will — become blissfully lost.

But this is precisely what I, and millions of others, enjoy. And Sanderson’s prosaic prowess is on full display in Oathbringer. “In the best prose,” as Arthur Clutton-Brock put it in his essay The Cardinal Virtue of Prose, “we are so led on as we read, that we do not stop to applaud the writer, nor do we stop to question him.” Indeed, rarely does Sanderson puncture the fourth wall of the narrative with a poetic flourish, drawing attention to himself rather than the story at hand. His discipline helps to make this a story in which you can — and should, and will — become blissfully lost.

But why bother to get lost at all if the place you’re losing yourself isn’t worthwhile? Here we come to Sanderson’s true genius: creating compelling, instructive worlds and peopling them with compelling, instructive characters. And when it comes to his worlds, the rule is simple: worse is better. Sanderson’s M.O. seems to be to create the most vivid, dark, smelly, miserable, unstable locations he can think of, then set loose a cast of characters and see how they react. The now-classic example is that of Vin and Elend, Mistborn’s protagonists, wading hip-deep through never-ending volcanic ash toward the literal end of the world. “Bleak” doesn’t begin to cover it.

The world of The Stormlight Archive, like that of Mistborn, seems like a miserable place to be. A good portion of Sanderson’s magic comes in making you want to be there anyway, for as long as you can. Such is the case with Oathbringer. If my chief complaint with the book is its length, then next in line is that I can’t spend another thousand pages on Roshar.

“Your words are not that special, Brandon Sanderson.” That’s up for debate, I suppose, though I know where I’d come down. What’s not up for debate is that Sanderson’s worlds are indeed that special.

Review: The Time Traveler’s Handbook, by Wyllie, Acton, and Goldblatt

The Time Traveler’s Handbook (Harper Design 2016), researched and written by James Wyllie, Johnny Acton, and David Goldblatt, bills itself as a guide book for a tourism company that sends people back in time to any of 18 different moments in history, so that one may witness the moment for themselves. Why travel to see the ruins of Pompeii, when you can travel to 79 AD in order to watch the very event that has made that city famous in history?

The Time Traveler’s Handbook (Harper Design 2016), researched and written by James Wyllie, Johnny Acton, and David Goldblatt, bills itself as a guide book for a tourism company that sends people back in time to any of 18 different moments in history, so that one may witness the moment for themselves. Why travel to see the ruins of Pompeii, when you can travel to 79 AD in order to watch the very event that has made that city famous in history?

The concept is a good one, but when I started the novel, which begins with a historic meeting of King Henry VIII of England and King Francis I of France, I soon learned the true purpose of the book. The three authors have taken 18 moments in time, meticulously researched them to near infinite detail, and presented them here, in the guise of fiction. At first, I was almost insulted. Why not just write this as a history book, and show us these wonderfully crafted and well-researched moments? Why use time travel as a kid’s spoon shaped like an airplane, making landing noises as you have us eat carrots by pretending our mouths are the hanger? The descriptions of the tent cities and ceremonies of the two kings was very well done, but I was annoyed that the authors thought I needed this device, even as I realized that I did indeed only pick up the book because of the time travel angle.

And then the next chapter came, the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, and I was hooked. I grudgingly admitted that I needed to occasionally be spoon fed things like this, and I ate it up! The description of the World’s Fair really captured me. One of the most fascinating to me was the Boer War Exhibit, which had 600 actors to reenact battles from the Anglo-South African War, many of whom were veterans of that war from both sides! Anthropological areas like the Philippines Village, which had the U.S. Department of War assemble 1,200 Filipinos to mimic their everyday life in a sort of reservation. Replicas of sections of several foreign cities or monuments, such as the Wailing Wall, or the Dome of the Rock, with each one populated by real Muslims, Jews, etc. The exhibits and displays went on and on, all incredible in different ways. Imagine how an exhibit featuring a working slaughterhouse would go over now, as children file through to watch animals killed and butchered. I found myself marveling at what the sheer size of the fair must have been, and how I’d never seen anything quite like it in my lifetime.

From then on, they had me, and I thoroughly enjoyed the book. Some chapters were naturally more interesting than others, more a sign of being parallel with my interests, and not a reflection that the other sections were in any way weak or inferior. I found myself not as involved with Opening Night at Shakespeare’s Globe, and then they would have me eating up every written detail the next chapter for the Golden Age of Hollywood.

One small issue with the entire concept is that since it is billed as a tour guide of sorts, there is no narrative. The book merely ends, with no sort of wrap up, conclusion, or summary. There is no hero to celebrate, no enemy to see vanquished. It finishes its description of your journey to see the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861, and then it ends. That’s fine really, it had no plot to wrap up. It just felt a bit… abrupt.

Still, it is an incredibly thorough book, with plenty of details to immerse in the selected time periods, always being sure to address clothes, food and drink, methods of travel, lingo or slang of the time, and then throwing in things like where and when you will arrive and depart to these locations. They helpfully include dos and don’ts at each step, so as to give you the best bang for your buck (and also, so as to avoid accidentally altering the past).

I highly recommend the book.

Review: Dreams of Distant Shores by Patricia A. McKillip

Every time I have read one of Patricia A. McKillip‘s novels, I have been struck by her poetic language and the vibrancy of her fantastical worlds. Therefore, I was delighted to have a chance to read and review an advance review copy of her latest collection of short fiction, Dreams of Distant Shores (to be published June 14, 2016). The book collects seven works of short fiction, one essay by McKillip, and a warm and insightful afterword by Peter S. Beagle. McKillip’s essay is about her style of writing high fantasy, which involves simultaneously following and breaking the rules of the genre. I enjoyed the glimpse into her writing process, and I think the balance between tradition and originality that she describes is one of the things that has kept drawing me back to her fiction.

Every time I have read one of Patricia A. McKillip‘s novels, I have been struck by her poetic language and the vibrancy of her fantastical worlds. Therefore, I was delighted to have a chance to read and review an advance review copy of her latest collection of short fiction, Dreams of Distant Shores (to be published June 14, 2016). The book collects seven works of short fiction, one essay by McKillip, and a warm and insightful afterword by Peter S. Beagle. McKillip’s essay is about her style of writing high fantasy, which involves simultaneously following and breaking the rules of the genre. I enjoyed the glimpse into her writing process, and I think the balance between tradition and originality that she describes is one of the things that has kept drawing me back to her fiction.

The short fiction in Dreams of Distant Shores, though, is far from traditional high fantasy. There are no queens, courts and heroes, and the stories take place in worlds not unlike our own. I thought the title itself was a remarkably accurate description of the contents within, since each tale felt like a dream permeated by a different style of magic. The vein of strangeness that runs through every work ties the collection of stories together.

The book opens with the confusing and surreal “Weird”. A man and a woman are locked in a bathroom with a gourmet food basket, while someone or something attempts to break in. The two of them seem oddly calm, and the woman recounts the weirdest things that have happened in her life. It’s a strange slice of a story, and reading it feels like falling into a fragment of someone else’s nightmare. The story “Edith and Henry Go Motoring” (original to the collection) also feels like a peek into someone else’s dream, though a more peaceful one. Edith and Henry go on an aimless journey in the English countryside, crossing a bridge with an unusual toll to an unexpected destination. I felt that these two stories were the most subtle and elusive of the collection, and I ended up reading them multiple times to try to gain a better understanding.

“Alien” (original to this collection) is another calm tale, and one that feels more grounded in a mundane reality. It features an elderly woman who claims to be visited by aliens, though her family fears she’s losing her mind. It’s a lovely and quiet story about growing old, familial relationships, loneliness, and wonder. Also, I think it must be the most positive alien abduction experience I have ever read.

Moving to the lighter side of the collection, “Mer” (original to the collection) and “Which Witch” are humorous stories with very different takes on the subject of witchcraft. “Mer” follows an immortal, form-changing witch who just wants to settle down into something comfortable and rest. In the process, she spends some time as a goddess and a wooden mermaid, and gets involved in an unusual local religion. The story is much less about the witch herself, who just wants a long nap, than it is about the ordinary people with whom she winds up getting entangled. The vagueness of the magic system works well within the story, since a lot of the humor comes from the characters’ exasperation with the confusing events happening around them.

Rather than the ancient, formless, sleepy witch in “Mer”, “Which Witch” follows a fashionable young woman in a witchy rock band. She’s proud to have recently acquired a crow familiar, but the two of them are having issues with communication. Unfortunately, what the crow is failing to communicate at the beginning of the story is, “You are in terrible danger!” The magic in this story is tied up in music, something that I think is pretty hard to pull off in a written story. I thought the music as magic sections were pretty fun in this case, though I’m not convinced the musicians would have put on a decent performance!

Moving into the longer fiction, “Gorgon in the Cupboard” was my favorite of the collection. The story involves a community of Victorian painters and models, and the kinds of relationships that exist between them. A middling painter searching for inspiration finds his muse in Medusa, whose spirit manifests in his unfinished painting of Persephone. Medusa directs him to search for a model, and he looks for someone who will stop him in his tracks and elevate his work. However, that model is more than a symbol or a mythological figure, but a human woman with her own griefs, thoughts, and dreams. What follows is an emotional story about how people are shaped by their experiences, and the value of seeing others as they truly are.

The final novella in the collection, “Something Rich and Strange” is a lyrical and imaginative story that carries an overt environmental message. A couple that lives by the coast have a stable life together, until supernatural forces slowly begin to tear it apart. The man is drawn inexorably to the water by a siren’s call, while the woman begins to see strange things in the familiar coastline. It is not long before the situation begins to get really out of hand. The story is beautifully written, and it had some pretty funny moments without losing its fundamental sincerity and gravity. I’m usually not a fan of including blatant messages in fiction, but the ocean really is in a sad state (though there are some signs of hope). Altogether, it is a haunting story of a relationship stretched to the breaking point, as well as a call to take responsibility for environmental damage.

In closing, this was an excellent collection of short fiction by Patricia A. McKillip. Each of the stories takes place in a different world, with a different tone and approach to the supernatural. With such a range, from the surreality of “Weird” to the Victorian painters of “Gorgon in the Cupboard”, I expect it will please fantasy fans with a variety of tastes. As for me, I have enjoyed visiting each of McKillip’s Dreams of Distant Shores.

Judith Merril’s Take On Classic Science Fiction

I have to thank Aqueduct Press (“Bringing Challenging Feminist Science Fiction to the Demanding Reader”) for publishing The Merril Theory of Lit’ry Criticism by Judith Merril. If you have sufficient years reading science fiction you’ll remember the annual SF collections of best short stories Judith Merril edited back in the 1950s and 1960s. What Ritch Calvin has done is collect all her introductions and summaries from those 1956-1969 annual anthologies, 38 book review columns from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (1965-1969), and a few additional essays from Extrapolation, a journal devoted to studying science fiction. For ebook readers, he also includes the introductions to all the short stories from all the anthologies. That’s 622 pages (ebook) or 360 pages (paperback) of commentary on science fiction, a goldmine of insight into old science fiction. Both editions are available from Amazon or the publisher, and hopefully your local bookstore.

I have to thank Aqueduct Press (“Bringing Challenging Feminist Science Fiction to the Demanding Reader”) for publishing The Merril Theory of Lit’ry Criticism by Judith Merril. If you have sufficient years reading science fiction you’ll remember the annual SF collections of best short stories Judith Merril edited back in the 1950s and 1960s. What Ritch Calvin has done is collect all her introductions and summaries from those 1956-1969 annual anthologies, 38 book review columns from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (1965-1969), and a few additional essays from Extrapolation, a journal devoted to studying science fiction. For ebook readers, he also includes the introductions to all the short stories from all the anthologies. That’s 622 pages (ebook) or 360 pages (paperback) of commentary on science fiction, a goldmine of insight into old science fiction. Both editions are available from Amazon or the publisher, and hopefully your local bookstore.

Judith Merril was an exceptionally well-read reviewer, not only referencing a detailed knowledge science fiction and its history, but literary works and science books. She was also pithy, funny and to the point. Here’s her 1965 review of PKD’s latest, where at the end of a previous book review had stated, “Philip Dick did it better three years ago, in The Man in the High Castle.” She then continues…

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Philip K. Dick, Doubleday, $4.95, 278 pp.

I don’t mean, this time, that his new book is similar in theme or treatment. Rather, that I wish it were more so, at least in characterizations and structure. Phil Dick is, one might say, the best writer s-f has produced, on every third Tuesday. In between times, he ranges wildly from unforgivable carelessness to craftsman-like high competence. In the case of Palmer Eldritch, I would guess he did his thinking on those odd Tuesdays, or rather on one of them, and the actual writing in every possible minute before another Good Tuesday came on him. Here is a riotous profusion of ideas, enough for a dozen novels, or one really good one; but the stuff is unsorted, frequently incompleted, seldom even clearly stated. The style is alternately dream-slow-surreal and fast-action-pulp. Thematically, he at least approaches, and sometimes stops to consider, virtually every current crucial issue: drug addiction, sexual mores, over-population, the economic structure of society, the nature of the religious experience, parapsychology, the evolution of man — you name it, you’ll find it. The book, with all this, is inevitably colorful, provocative, and (frustratingly) readable. I wish I thought it possible that Dick might some time go back to this one, publication notwithstanding, and finish writing it.

One reason why I immediately hit the buy button for The Merril Theory of Lit’ry Criticism is because I bought her anthologies a half-century ago, and started reading F&SF around that time too. For years now I’ve been meaning to order those anthologies used from ABEBooks, just so I could read the commentaries. To have Calvin throw in all the book reviews was too good to be true, but it is.

I’ve been hung up on my science fictional past, and this book is perfect for retracing steps I first took in 1965. Anyone who collects old SF from that era will find this volume to be a treasure chest of clues.

Merril, on occasion, had a lot to say about a book. She often read a book more than once to write a review. She was determined to understand science fiction at a level beyond what most readers ever try. Look at this review of Nova by Samuel R. Delany, one the more memorably SF books from the 1960s. I probably read this review at the time too. This is a great example of what Merril does when she goes long:

Leave your preconceptions behind, again, when you open Samuel Delany’s new Nova (Doubleday, $4.95). My own problem was the opposite of my friend’s with 2001: I came to this book with an anticipation keener than any I have brought to anything since — well, probably Vonnegut’s Rosewater — looking for (at least an approach to) the Great Novel I (still) expect from the author of Empire Star, Babel-17, The Einstein Intersection, “The Star-Pit,” “Aye and Gomorrah,” and (now) Nova: and what I got instead was a first-rate jim-dandy solid provocative science-fiction novel.

It took me a while to realize I had no honest cause for complaint — a while longer to discover I damn well did have cause — longer yet to understand (first) why I was so irritated, and (eventually) the real reasons to be annoyed with the book.

Delany is in an almost unique position in s-f today: everybody loves him. The “solid core,” the casual readers, the literary dippers-in, the “new thing” crowd — Delany is all things to all readers. It is an untenable position — unless, of course, he gets as good as I think he will eventually be. Swift, Melville, Carroll, Twain, Conrad are all read by children as well as litterateurs, their plots are reducible to comic book format, while their themes are subtle and complex enough to sustain reading after delighted analytical reading.

Well, Delany is not Swift or Conrad — yet; but his seven previous novels and scattered shorter works have already placed him out of the judging in the transient-writer class; and as the work of an apprentice-great, Nova must be regarded as more of a fascinating exercise than a satisfactory achievement. But —

What is wrong with the book is simply that the author tried to do — not too much, but enough: he tried to write a modern novel on all the levels required (by the same standards I am applying) of a contemporary work: if he did not quite succeed, it is well to remember that neither has anyone else — yet; and few other attempts have managed to stand up meanwhile as, at least, solid entertainment.

Here is what I wrote after my first reading of the book:

Nova is a deceptive book in several ways. Don’t let the first page stop you; the book is not — except superficially — a Planet Stories superficiality. And don’t rush in to identify with anyone too soon; it may take a while to decide whose viewpoint you are using.

The protagonist, the hero, and the viewpoint character are (in order of appearance, not necessarily identity) a 19-year-old gypsy-born spacehand-and-minstrel named the Mouse; a cosmically wealthy and powerful space captain named Lorq Von Ray; and a wandering scholar and spacehand called Katin.

The book is intriguingly, but unnecessarily, complex — mostly written underwater, as it were; that is, under the surface of a (too) familiar space adventure plot, as warm and sparkling with the strange and rich biota of Delany’s inner world.

There is, for instance, the Mouse’s “sensory-syrynx,” an instrument which can produce a complete multi-media show — visual, musical, and olfactory display; a recurrent theme involving Tarot lore; a carefully constructed cultural context in which the 20th century serves as the classical period of a culture 1000 years older, whose technological and philosophic beginnings are rooted in the transitions of today. There are the Illyrion furnaces which have made whole planets habitable and space traversable, great glowing pits called Hell here, and Gold there — and tiny battery power packs primed by micrograms of the same stuff, which run the wondrous syrynx and Katin’s tiny recorder. There is a gorgeous physiological/astrophysical/political philosophic construct in parallels; and a sweep of action from Athens to the Pleiades, with fiery fights, drinking bouts, mosques and museums, diver-hunters and cyborg-spacemen — and with all this, the book is somehow lacking. I do not know what it lacks; perhaps if it had come after Empire Star and Babel-17, and before The Einstein Intersection, I should have found no lack, at all. But, just as I went on from the first banal page, simply because it was Delany, and I could be sure of finding the richness and excitement I did find, so I went on from history lesson to battle scene to gorgeous syrynx session to Tarot lore, hoping I could be equally sure of learning why they were all there together. I think an explanation was given to me in the last pages — and I do not think it satisfied me. But never mind: the fans will love it.

That was the first time around; I have now read the book — to be precise — two and a half times (the third time, only those passages marked the second time for re-examination), and when I started to retype that earlier comment, I thought the word unnecessarily must have been a typographical error. Alas, not so: the error was not mechanical, but (doubly) human — the reader’s and writer’s both.

There is nothing in this book that did not have to be there — from the blind drunk of the spacebars to the wicked gorgeous Princess, Ruby Red; from the syntax-inversion of the Pleiades speech-pattern to Katin’s erudite lectures; from the cool halls of the Alkane Institute to the hole in the stellar doughnut. The problem is rather that some elements are so compressed as to be almost invisible, and I question whether any reader who lacks the responsibility of recording his opinion will work as hard as I did to find, and put together, all the pieces in a book so readily readable and pleasingly paced on the surface that there is no real cause to wonder how deep the channels underneath may flow — and small sign of their turbulence.

These are (at least some of) the ways you can read Nova: as a fast-action far-flung interstellar adventure; as archetypal mystical/mythical allegory (in which the Tarot and the Grail both figure prominently); as modern-myth told in the s-f idiom with powerful symbols built on solid science fiction clichés; as a futuristic vehicle for a philosophic complex of political/historical/economic/sociological ideas; as an experimental approach to literary criticism.

Among other things, the book examines: the nature and value of scholarship, mysticism, “progress,” and the varieties of the creative experience; the significance of the “instinct for workmanship” (the quote is from Veblen, not Delany) and the alienation phenomena of the industrial and (current) electronic revolutions; the relationships between the psychophysiology of the individual and the ecology of the body politic. Each of the three central characters (or the three aspects of the character?) suffers a variant form of alienation, rooted in different combinations of social, economic, geophysical, cultural, intellectual, and physiological factors. Through one or another of these viewpoints, the reader observes, recollects, or participates in a range of personal human experience including violent pain and disfigurement, sensory deprivation and overload, man-machine communion, the drug experience, the creative experience — and interpersonal relationships which include incest and assassination, father-son, leader-follower, human-pet, and lots more.

The economy of Delany’s writing is both maddening and delightful — and almost accomplishes what he seems to have been trying to do. (For instance, the culture-vista opened up when the Lunar scholar, Katin, says to the gypsy Mouse: “If somebody had told me I’d be working in the same crew, today in the 31st century, with somebody who could honestly be skeptical about the Tarot, I don’t think I would have believed it. You’re really from Earth?”) But even 279 closely written, richly embroidered, tautly thought pages are not enough: it is too much of too many, and too little of each: and — add odd complaints — it is too easy to read, on the easiest level.

If you let yourself go, it will run away with you; since the author failed to set up stop signs, the reader must either make his own (put the book down and pace the room once between chapters?) or plan on a second, slower reading after the fun of the first. Or settle, of course, for a good read, and never mind mining out the gold.

For two writers so disparately individual in concept, mood, style, background, and viewpoint Delany and R. A. Lafferty have certain startling distinctions in common. There are other notable stylists and fine prose writers in s-f today; but — in very different modes — Lafferty and Delany are currently the two outstanding poetic writers (language both lyrical and precise; images exact and evocative). There are other evolving new concepts and working out appropriate new techniques for contemporary multiplexities; and there are many others writing action-adventure yarns in the s-f idiom; but I can think of no others who so frequently manage to combine these apparently contradictory efforts.

But their greatest similarity also contains their most symptomatic difference. Among the characters in both men’s stories, a strange breed of children appear repeatedly: hardheaded/mystical creatures with electric personalities and powerful capacities. In Delany’s stories they are most often young teenagers whose essentially heroic proportions and proclivities (like almost all Delany characters) are dramatically flawed, or defective, or incurably disadvantaged, in some one area. Lafferty’s children are mostly prepubescent, and perfectly normal — except for a total lack of (parental or personal) inhibition; and a sort of amplification — of reality which permits them to act out archetypal childish fantasies on a grand-opera heroic scale.

By the way, Nova, as well as Babel-17 and Dhalgren have been recently produced for audio, and are available at Audible.com. I waited over a decade for Delany to come to audio, and the wait was well worth it, because hearing Delany read by a professional makes his rich narrative come alive in myriads of ways my own inner voice fails to find. I beg the audiobook producer gods to please come out with Distant Stars and Aye, and Gomorrah: And Other Stories next. They contain the short novel and novella, Empire Star and “The Star Pit” which are my absolute favorite science fiction stories form the 1960s.

By the way, Nova, as well as Babel-17 and Dhalgren have been recently produced for audio, and are available at Audible.com. I waited over a decade for Delany to come to audio, and the wait was well worth it, because hearing Delany read by a professional makes his rich narrative come alive in myriads of ways my own inner voice fails to find. I beg the audiobook producer gods to please come out with Distant Stars and Aye, and Gomorrah: And Other Stories next. They contain the short novel and novella, Empire Star and “The Star Pit” which are my absolute favorite science fiction stories form the 1960s.

If you’re the kind of science fiction fan I am, old and looking backwards, analyzing a lifetime of reading, The Merril Theory of Lit’ry Criticism is a book you won’t want to miss. The ebook is a real convenience, letting us read a few reviews on our phones whenever a free moment pops up.

Judith Merril also wrote science fiction, not much, but enough to make her one of the pioneer women writers of science fiction starting in 1948 with her classic short story, “That Only a Mother” appearing in Astounding. She wrote two novels on her own, Shadow on the Hearth (1950) and The Tomorrow People (1960), and two novels with C. M. Kornbluth as Cyril Judd, Gunner Cade (1952) and Outpost Mars (1952). Shadow on the Hearth and the two Cyril Judd novels have been collected by NESFA Press as Space Out: Three Novels of Tomorrow by Judith Merril and C. M. Kornbluth. The Tomorrow People is currently in print from Armchair Fiction, a company that reprints a great deal of forgotten science fiction.

Judith Merril also wrote science fiction, not much, but enough to make her one of the pioneer women writers of science fiction starting in 1948 with her classic short story, “That Only a Mother” appearing in Astounding. She wrote two novels on her own, Shadow on the Hearth (1950) and The Tomorrow People (1960), and two novels with C. M. Kornbluth as Cyril Judd, Gunner Cade (1952) and Outpost Mars (1952). Shadow on the Hearth and the two Cyril Judd novels have been collected by NESFA Press as Space Out: Three Novels of Tomorrow by Judith Merril and C. M. Kornbluth. The Tomorrow People is currently in print from Armchair Fiction, a company that reprints a great deal of forgotten science fiction.

Merril produced several short story collections: Out of Bounds (1960), Daughters of Earth (1968), and Survival Ship and Other Stories (1974), each of which has been repackaged a number of times, but all her stories are currently available as Homecalling and Other Stories: The Compete Solo Short SF of Judith Merril (2005), again from NESFA Press.

I hope both the NESFA books come to audio.

Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee

Yoon Ha Lee—a familiar name to short fiction readers—has published over forty stories since 1999 in most of the major venues, receiving several award nominations and numerous appearances in Year’s Best anthologies along the way. With Ninefox Gambit, Lee has made the transition to the novel (and thus to the possibility of a much larger audience) in a major way, with the first volume in a promised trilogy collectively titled The Machineries of Empire. A highly inventive far future military space opera filled with complex political intrigue and strange technologies, it may take an greater-than-usual amount of the reader’s patience and attention to come into focus, but the effort pays off as we are ultimately rewarded with a trip into a unique future setting for the story of a soldier who gradually discovers her role in a series of power machinations between an authoritarian status quo and a rebellion with the potential to move humanity (as well as some sentient robots) toward a more individualistic and democratic future. The same heavy use of specialized jargon and unfamiliar technologies that make the novel a challenging, fascinating and rewarding read also make it somewhat difficult to summarize and review, but here we go…

Yoon Ha Lee—a familiar name to short fiction readers—has published over forty stories since 1999 in most of the major venues, receiving several award nominations and numerous appearances in Year’s Best anthologies along the way. With Ninefox Gambit, Lee has made the transition to the novel (and thus to the possibility of a much larger audience) in a major way, with the first volume in a promised trilogy collectively titled The Machineries of Empire. A highly inventive far future military space opera filled with complex political intrigue and strange technologies, it may take an greater-than-usual amount of the reader’s patience and attention to come into focus, but the effort pays off as we are ultimately rewarded with a trip into a unique future setting for the story of a soldier who gradually discovers her role in a series of power machinations between an authoritarian status quo and a rebellion with the potential to move humanity (as well as some sentient robots) toward a more individualistic and democratic future. The same heavy use of specialized jargon and unfamiliar technologies that make the novel a challenging, fascinating and rewarding read also make it somewhat difficult to summarize and review, but here we go…

The ruling Hexarchate of numerous worlds is made up of six factions, each with a specialized role within the governing structure. Kel Cheris, whose mathematical abilities would have suited her for the math-based Narai faction, chose instead to join the Kel military faction. The Kel are known for their unwavering loyalty and obedience to the hierarchy they are part of, a loyalty ensured by their artificially instilled “formation instinct”. Like many of the concepts in Ninefox Gambit, the precise nature of this “instinct” is not entirely clear, though its effects are plain enough. For the Kel, instant obedience to orders is necessary for their military success, which is based on the use of mathematically derived soldier formations adapted to the particular circumstances of battle. Cheris’s mathematical talents allow her to rise within the Kel ranks, as her ability to quickly calculate these formations is highly valuable to the Kel and thus to the Hexarchate.

Prior to the events in the novel, the Hexarchate had been a Heptarchate, but the seventh faction—the Liozh (the philosophers and leaders) broke away in a rebellion, and Cheris has been recruited to lead the forces being sent to counter this latest turn in the rebellion. The Liozh have captured a strategic “nexus fortress”, and the Hexarchate desperately wants it back. In the world of the novel, rebellion against the Hexarchate takes on the character of religious heresy, as the stability of the Hexarchate, echoed in a sense by the stability of the Kel military formations, is dependent not just on each faction and each individual maintaining a proper role within it, but by the maintenance of belief in this system, based on a mathematical “high calendar”: “consensus mechanics meant the high calendar’s exotic technologies would only work if everyone observed the remembrances and adhered to the social order,” and the more important these technologies become to the Hexarchate, the more rigid the social system must be. Social rigidity, however, inevitably leads to rebellion, and deviation from orthodoxy leads to “calendrical rot.” (I may be reading too much into the mathematical aspects of the story, but I found the pattern of the Hexarchate reminiscent of a fractal pattern, and the concept of the numerical stability of Kel formations similar to electron shells in physics. In any case, math fans will find much of interest in this novel!)

Cheris, then, is tasked with taking back nexus Fortress of Scattered Needles from the heretics—a station/fortress that is itself a “microcosm of the Hexarchate,” and one of whose functions is to “project calendrical stability throughout the region. If it had fallen to calendrical rot, the Hexarchate’s exotic weapons would be of limited use there. The Hexarchate lagged in invariate technology, which could be used under any calendrical regime. In particular, too close to rot the voidmoths’ [spaceships’]primary stardrives would fail. Without the voidmoths to connect the Hexarchate’s worlds, the realm would unravel. If the heretics converted the Fortress to their own calendrical system, the problem became critical. The Hexarchate would have to contend with a rival power at the heart of its richest systems.”

One of the exotic technologies available to the Hexarchate is the “black cradle”—a device that stores an uploaded mind, conferring a sort of immortality on the chosen individual. The black cradle is rarely used, however, since living bodies are required to bring the stored personalities back to life, not to mention the tendency of its use to lead to violent madness in its subjects. The importance of Cheris’s mission is thus indicated by the decision to retrieve the mind of the legendary general Shuos Jedao to help with the mission. Jedao’s mind is removed from the black cradle and moved directly into Cheris’s mind, where the two personalities must co-exist for the duration of the mission. Jedao has been dead for four-hundred years, executed for treason after purposely destroying his own forces in a crucial battle against heretics—an action attributed to madness. His mind is preserved for its strategic brilliance, however, since he never lost a battle during his military career. Cheris, then, must try to make use of Jedao’s advice on military strategy, while keeping her own personality intact against the possible onslaught of Jedao’s madness.

The combination of Jedao’s strategic knowledge and experience and Cheris’s mathematical talent and adaptability make them a formidable combination, as she/he/they approach the Fortress of Shattered Needles, where the spread of calendrical rot makes their technologies unreliable. Computational attacks, kaleidoscope bombs, invariant ice shields, logic grenades, threshold winnowers, carrion bombs: these are just some of the “exotic technologies” that come into play in this calendrical war.

As the battle unfolds, Lee gradually reveals some of the politics that underlie this “game between competing sets of rules.” At one point, the nature of the Liozh heresy is suggested: “’An obscure experimental form of government where citizens choose their own leaders or policies by voting on them.’ Cheris tried to imagine this and failed. How could you form a stable regime this way? Wouldn’t it destroy the reliability of the calendar and all its associated technology?” The readers’ sympathies are with Cheris, but we have to wonder from the start about the cause she fights for, and the means used by the Hexarchate to maintain their power. (The too-easy sacrifice of individuals for the good of the group is a recurring theme, for example.) Judgment must be reserved, however, as the underlying motivations of those involved in both sides of this war are not fully revealed, and I suspect that the readers’ tendency to choose democracy over authoritarianism (or, in the context of the novel, heresy over orthodoxy) may be too simple a judgment. Setting up questions and doubts about the players and politics involved in the story, though, is clearly one of Lee’s goals in Ninefox Gambit, whetting the reader’s appetite for the rest of the trilogy. In the sequels, which I’m definitely anticipating, I’ll be looking for how Lee resolves this underlying theme of the balancing of the benefits of social cohesion and the rewards of individualism.

Much as I enjoy speculating about the political implications of science fictional futures, then, judgment must be reserved in the case of Ninefox Gambit, as much will be determined by the direction of the sequels. This opening novel is well worth reading, though, for its intriguing setup of a unique space opera setting, a taste of which I have tried to give in this review, and for the Cheris/Jedao character arc. Not much can be said about the specifics without spoiling the story, but the nature of his/her/their relationship evolves unexpectedly with events. Cheris learns things about Jedao that were not in her history books, and that shed light on the longer-term conflict between the Hexarchate and the heretics, while the mechanics and psychological implications of the two personalities in a single mind/body are interesting in themselves. This strange relationship does reach a resolution within the novel, but this conclusion, in the best trilogy tradition, also serves to raise the urgent question of where the story and our combined protagonist will go next.

Based on this opening gambit, there’s a good chance that this series will be seen as an important addition to the space opera resurgence of recent years. While Lee has developed a singular combination of military SF, mathematical elegance, and futuristic strangeness (as Gareth Powell puts it in a cover blurb: “As if Cordwainer Smith had written a Warhammer novel”), readers may note echoes of or similarities to Iain M. Banks, Hannu Rajaniemi, C. J. Cherryh, Ann Leckie (and, yes, Cordwainer Smith). Admirers of these authors, or anyone interested in state-of-the-art space opera, ought to give Ninefox Gambit a try.

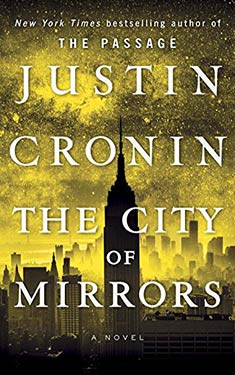

The City of Mirrors by Justin Cronin

Note: This review contains spoilers.

The year was 2010. The vampire fiction genre was still trying to recover from the horror that was the “Twilight Saga.” In among these sparkly vampires came The Passage by Justin Cronin. The vampires in this novel had more in common with “Nosferatu” than with either Edward Cullen or Count Dracula. The Passage was followed in time by The Twelve, and now six years after we the reader were introduced to Amy and her intrepid band of vampire hunters, this series comes to a shattering conclusion with The City of Mirrors.

I knew this novel was going to be a challenge from the start. Justin Cronin is not the easiest author to read. His tendency to play fast and loose with the flow of time can be a challenge to read. Chapters do not flow in a chronological order, jumping from before the viral outbreak, to 20 years after the events in the second book, The Twelve, and then forward 1,000 years after the outbreak. But because his world building and character development are surpassed by none, this reader at least is willing to wade through the chronological ping pong. Because I care about the characters and the gloriously detailed world these characters inhabit.

Mr. Cronin must thoroughly enjoy playing fast and loose with his reader’s emotions. All the major heroes in the story have tragic and heartbreaking back stories. In The City of Mirrors the reader is reintroduced to Timothy Fanning, patient zero of the outbreak. The author does a wonderful job of showing us how broken Mr. Fanning was before he was infected. I even started to feel sorry for him. [And then he killed his former student.] All of a sudden, due to one action by Fanning most of the sympathy I had for him was yanked from me like the proverbial rug. Mr. Cronin goes on to further twist that sympathy to its breaking point with every action Fanning/Zero performs in the entire second half of the book.

As in the second novel in the series, there is a strong element of religion, or at least some kind of omnipotent presence guiding the actions of the characters. This should not dissuade the non-religious reader from this book. Left Behind this ain’t. In fact, I would go so far as to say any evangelical who reads this book is going to be steaming mad by the ending. Even your basic Christian may find issue with the complete lack of devine retribution. [Fanning dying and being able to spend eternity in his happiest memories.]

The irony of this novel is that Justin Cronin tried his damnedest to give this a happy ending, and in general he succeeded. Because for him the afterlife appears to be for everyone. [Living in the memory that is happiest for the person.] Humanity survives and flourishes, the heroes both living and dead are rewarded in the best way they can be, and the vampire virus is beaten back.

But because this is Justin Cronin, the one character who deserved peace and happiness is denied this reward. The final moments of this novel are perhaps some of the most bittersweet pages I have ever read. When the final chapter was finished I set the book down and wept. I’ll be honest, Mr. Cronin may have a hard time topping this series with his next book.

6 out of 5 stars (seriously, this book deserves more than 5 stars)

She Who Watches by Anthony Pryor

Some books are just a fail with me. In general, I hesitate to give a book a low review just because I did not enjoy it, I mean 80% of a review is in the reader’s perspective. We have all reread a book we once loved and on a second read couldn’t help but wonder what kind of crack we were smoking to have enjoyed the book so much the first time, and visa-versa. But in the case of She Who Watches, by Anthony Pryor I really do not feel much guilt for this review.

Some books are just a fail with me. In general, I hesitate to give a book a low review just because I did not enjoy it, I mean 80% of a review is in the reader’s perspective. We have all reread a book we once loved and on a second read couldn’t help but wonder what kind of crack we were smoking to have enjoyed the book so much the first time, and visa-versa. But in the case of She Who Watches, by Anthony Pryor I really do not feel much guilt for this review.

The characters were one dimensional. The female characters were particularly offensive to me. There were only two female leads, the first Trish, is apparently the group pump. Her main and only characteristic is sleeping with all the members of the group, well most of them anyways. She is possessed by the demon before she gets through all of them. Her one main scene in the book is the obligatory sex scene with the main character. I’m not sure why the author felt he needed to cut and paste a scene from Fifty Shades of Grey into his book, but he did. Trish boils down to little more than a trampoline for the main character.

The other female lead Kay, was mousy and weak. When she steps up to fight the demon, the main character is surprised, even though in the previous two paragraphs the author goes into details about how one of the male main characters, and even the dog have become more powerful and more committed to destroying the demon after having an experience of seeing a goddess. My only thought while reading this description was, why would he be shocked that she was moved, he wasn’t surprised when the rest of the group was moved and motivated by meeting a goddess!

The rest of the characters were equally one dimensional. I felt no vested interest in their wellbeing and by the end of the book was counting how many pages I had left before I could read something else.

But because of who I am, I am going to leave this review on a positive note. At least the author didn’t kill the dog.

I would like to thank Permuted Press, for providing this book for an honest review.

HEX – Thomas Olde Heuvelt

Horror books come in two basic types, there is the “grab-you-by-your-throat” and the “slow burn.” Done well, both novels can be terrifying, and if a novel is able to give the reader both in the same book, that author should be dubbed a master of their field. Well I say hat’s off to “Master” Thomas Olde Heuvelt for the American debut of his novel HEX. I was hooked by this glorious piece of work from the very start. I finished it in 4 days, and probably would have finished it sooner if pesky things like work, food, and sleep had not gotten in my way!

Horror books come in two basic types, there is the “grab-you-by-your-throat” and the “slow burn.” Done well, both novels can be terrifying, and if a novel is able to give the reader both in the same book, that author should be dubbed a master of their field. Well I say hat’s off to “Master” Thomas Olde Heuvelt for the American debut of his novel HEX. I was hooked by this glorious piece of work from the very start. I finished it in 4 days, and probably would have finished it sooner if pesky things like work, food, and sleep had not gotten in my way!

This novel brings to mind Stephen King. Not so much in writing style but in his ability to strip away the picturesque façade of Small-Town “America.” Black Springs is a typical Up-State New York town. If you read the book jacket you go into this novel knowing that the town is hiding a secret from the rest of the world. Katherine, The Black Rock Witch, has been haunting the village for over 300 years. She appears randomly anywhere in the town, and when I say anywhere I mean in the townspeople’s living room while enjoying a movie, or in their bedroom while making love. The residents of the town have learned to cope with her appearances. There is an entire quasi-military organization called “HEX” to deal with her, and deal with her they do.

HEX grabbed my attention for the very beginning. The best way to describe this novel is like frying food. I know, bear with me. When a cook first puts the oil on the heat, there really is not much to see. I mean, they know the oil is heating up, but there is no real action. Then the cook will start to see the occasional bubble lift to the surface or a wisp of smoke, but add the food and all that energy and force that has been hiding below the surface flares up in a riot of bubbles and foam. The reader knows there is a terrible problem forming in Black Springs, heck the characters know it also, but like the reader, they are powerless to stop it.

What drew me to this story was the dichotomy of small town life and modern technology. HEX had established a high-speed internet service for the entire town and all residents were issued a smartphone so they could have access to an app, documenting the location of the witch. The entire town is complicit in keeping the secret of the witch from the larger world. Because this novel is set in present day, the reader is able to watch the members of the community, and HEX specifically, deal with the possibility of the witch’s discovery through technology.

Why is it so important to keep this witch secret? Because the curse is more than the witch. People who are born in the town and people who move into the town can never leave. If they try to leave, even for an extended vacation, they become suicidal until they return to the town. At some point in the history of the town, the elders managed to sew-up the witches’ eyes and mouth, and bind her hands in chains. This was because listening to her causes the residents to also become suicidal. The couple of times residents tried to remove the bindings, there were deaths in the town.

In the end it is technology and misunderstandings that is the downfall of this community. As a reader, I spent most of this novel alternating between horror and sadness for the residents of Black Springs, all the residents, the living and the dead.

Now this is a translation of the 2013 Dutch original, and the author chose to “Americanize” it as opposed to a direct translation. This version of the novel is set in an American village. I don’t speak Dutch, so I have no way of telling how close this comes to the original, but this was a version of the novel written by the author himself, so I am going to go out on a limb and say that the spirit of the original is going to be included in this translation.

The English translation of this novel is being released on April 26, 2016. Run — do not walk — to get this book. I promise you will not be sorry.

Thank you, Tor Books, for providing this book for an honest review.

Recent Releases: The Deep Sea Diver’s Syndrome by Serge Brussolo

David Sarella works with a trusted crew. His accomplice Nadia is a gorgeous redhead dressed in black leather. Jorgo may be a bit simple-headed, but he is an excellent driver. They plan to break into an upscale jewelry store in an exclusive shopping district and empty the safe. Their immediate problem is that the sleek, black automobile they have chosen for this escapade is transforming into a shark. The metal frame has become slimy and the fish smell is unbearable. These are “stability issues,” and Nadia’s job is to monitor David, to see that he takes the proper maintenance drugs. The team is operating at a depth of 3300 feet, but they are already rising. David must complete the theft before he is forced to surface.

David is a master thief but a professional dreamer. In Serge Brussolo’s near-future Paris, mediums like David enter their dream worlds, perpetrate their crimes, and bring back their takes to the waking world. David’s dreams are informed by the pulp fiction he’s read since childhood, and the dreaming process is, as for most mediums, experienced as a plunge into ocean depths. He absconds with jewels that on the surface manifest themselves as mounds of ectoplasm, that white sticky stuff nineteenth century mediums supposedly exuded from their mouths, noses, and other orifices during séances.

But David and his fellow dreamers are not fakes. Their ectoplasmic creations, delicate a newborns, get whisked away for quarantine and testing. Once they are stable they go onto the art market, a market they have destroyed and transformed. Museums have sold off their collections of old art to junk dealers and replaced paintings and sculptures with ectolplasmic abstractions, the most accomplished of which sell in auction for millions. Our hero is not in that league. He makes a living as a minor artist whose works end up in museum gift shops. He’s more or less made his peace with that, but he is facing a crisis. Recently he’s come up empty handed after his dives, and some of what he has brought back is too feeble to make it past quarantine. His is the uncertain future of a failed artist.

Readers are left wondering for the first half of the story just what is the deal with this new art form? The descriptions of the objects are vague and not particularly appealing, but we learn that these creations make people feel good. They can make them feel really good. Even David’s tchotchkes lighten the spirits of those who collect them. A major work, like the monumental creations of Soler Mahus, can transform lives. David goes to revisit Soler’s magnum opus in its permanent public installation.

The great dream that had stopped the war had sat enthroned on Bliss Plaza for five years…It’s presence had driven up the apartment prices in the neighborhood, everyone wanting to live close to the work to benefit from its soothing emanations…residents in buildings overlooking Bliss Plaze were totally free of psychosomatic complaints. Better still: incurable diseases had completely vanished in a three hundred yard radius of the oneiric object. The lucky few lived with their windows open, naked most of the time…Those without the means to rent apartments nearby made pilgrimages to Bliss Plaza…a silent, naked crowd sprawled on the steps and grass.

As a practicing dreamer, David also knows the downside of ectoplasmic art. The objects have a shorter shelf life that of the old art. When they begin to decompose they not only stink, they become sticky and toxic. Art disposal is a growth industry, but there is a “finger in the dike” element to its struggle against a growing mountain of fetid art. And then there are the health problems faced by its creators. All that ectoplasm can never be fully expelled, and build up over time causes esophageal and pulmonary issues.

On one level, Brussolo’s novel is a satire on the distinctly Parisian vision of the starving artist in his garret, the failed genius in feverish pursuit of a vision that remains beyond his grasp. Despite his lessening powers and declining health, David cannot forsake his dream world, which is admittedly more vivid than the drab life he lives between dives. He will be willing to risk all for a final plunge to a greater depth than any dreamer has either ever attempted or lived to tell about.

The publishers describe The Deep Sea Diver’s Syndrome as a “visionary neo noir thriller.” There is a trace of marketing legerdemain here. David may be a trapped man in a system that once supported him and that now has little use for him, but Brussolo doesn’t employ the mounting tensions of David’s predicament to build suspense or a sense of panic. He creates an inventive progression of scenes that illustrate aspects of this bizarre world. The novel might better be described as “entertaining and very cerebral science fiction,” which admittedly doesn’t have the ring of ”visionary neo noir thriller.”

The good news for readers who find they like Brussolo’s technique and vision is that in France he has published somewhere in the neighborhood of 200 novels. The bad news is that this is his only work to have made its way into English, and there are no plans in place for future translations.

Bandersnatch – Lewis & Tolkien as Writers in Community

I’ve got to start with a misconception that people who don’t know artists or other creative people often have. Many people think that the creative process starts and ends in the space between the artist and the work. That is, in that space between the blank page and the writer, the blank canvas and the painter, or the raw stone and the sculptor. This is only partially true and this partial truth gives rise to the myth, yes Myth, of the writer in a lonely garret, the Eiffel Tower in the background, out the window. Yes, in that space is where everything collides in the struggle right then and there to create, but any artist will tell you that this point is only 50% of the process. (Some say more, some say less.) There is a wholly different side to the creative process which those who don’t know artists, know nothing about.

I’ve got to start with a misconception that people who don’t know artists or other creative people often have. Many people think that the creative process starts and ends in the space between the artist and the work. That is, in that space between the blank page and the writer, the blank canvas and the painter, or the raw stone and the sculptor. This is only partially true and this partial truth gives rise to the myth, yes Myth, of the writer in a lonely garret, the Eiffel Tower in the background, out the window. Yes, in that space is where everything collides in the struggle right then and there to create, but any artist will tell you that this point is only 50% of the process. (Some say more, some say less.) There is a wholly different side to the creative process which those who don’t know artists, know nothing about.

That is Bandersnatch: the other side where creativity is forged in the crucible of fellowship.

In terms of the 20th century, the Inklings, this select group of men, who met, talked, and critiqued each others work, has now become The Example for how a fellowship is supposed to work. Even Paris of Hemingway’s lost generation, with their salons, and creative minds from far more disciples, seems now a pale second place.

Bandersnatch takes us into this crucible, trying to reconstruct from a fly-on-the-wall perspective this extraordinary time and place. Glyer is concerned with two fundamental questions: What did they talk about when they discussed the various works in progress? and What difference did it make within the books they were writing?

These are simple but seemingly unanswerable questions. Until now, of course. It is positively amazing what a determined scholar can find, especially going into a headwind of opinion from friends, mentors, teachers, that these questions Can Not be answered, so one shouldn’t waste one’s time trying.

Thank goodness she didn’t listen to those little minds. The end result was the book The Company They Keep: Lewis, Tolkien as Writers in Community. Bandersnatch then is not the Good Parts version, the dumbed down for a general audience version, nor a more intimate treatment with the author as narrator version, although all three facets do come into play. Think of Bandersnatch as a distillation with an eye on bringing the practice, that is, the wisdom of The Inklings, into our own lives as creative people.

What did they talk about? What difference did it make? The answer is everything and the other answer is that it made a huge difference. You’ll have to get the details from the book!

For me, the book highlighted not just the critique part of fellowship, but also the resonating aspect, that is, someone who gets it like you get it. If, say, two anime Otaku (obsessed fans of Japanese animation) get together and one of them says “SAO” that’s all they need to engage in a 40 minute conversation concerning the minutia of “SAO” that is as incomprehensible to an outsider as if the outsider was listening to two astrophysicists. From what Glyer has gleamed from The Inklings and from a lot of current research and thought on the subject, this resonating aspect by itself is huge, in terms of creativity.

Glyer goes on to illuminate a half dozen other forms of feedback within the fellowship and what effect it had on the individual writers and their work. She also, fortunately or unfortunately, illuminates what ultimately sunk their ship: what went wrong and why it was their undoing. This, of course, should be a lesson for our own creative process.

If you are a Lewis or Tolkien fan, what are you waiting for? Go and get this book. If you don’t care for those two but the issues surrounding creativity, or writers in general are of interest, this book offers plenty for you as well.

Highly recommended.

Full Details

Full Details