GMRC Review: The Computer Connection by Alfred Bester

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog.

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog.

The Computer Connection by Alfred Bester

Published: Berkley/Putnam, 1975

Awards Nominated: Hugo, Nebula, and Locus SF Awards

The Book:

”There is a Group of eccentric immortals, who have all come into being after a shocking near-death experience. Some of them are actual historical celebrities, but others simply take on names that best describe their interests. Guig’s name comes from the “Grand Guignol”, and he earned it through his obsession with recruiting new immortals. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to orchestrate an experience of horrific near-death followed by a miraculous save, so all his attempts have ended in failure. Mostly, he just kills people in terrible ways—but with the best of intentions.

Guig has his sights set on a new recruit, a genius Cherokee scientist named Sequoya Guess. The conversion marks Guig’s first success, but then something unexpected happens. Guess has mysteriously formed a connection with a supercomputer known as the Extro. Guess may want to further his research and make life better for humankind, but the Extro has more homicidal intentions. Guig and his Group must face the terrible truth—if Guess can’t control the Extro, they may have to kill a man they think of as a brother.” ~Allie

This is my September novel for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. I picked this novel because I am generally a fan of Alfred Bester. He is a skilled wordsmith, and everything he writes seems to be brimming with energy and enthusiasm. While The Computer Connection was as ridiculous and energetic as usual, I don’t think it is one of his best novels. For any newcomers to Bester’s work, I would recommend starting with some of his more well-known novels, such as The Demolished Man or The Stars My Destination.

GMRC Review: The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s sixth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s sixth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

This will be the seventh Worlds Without End review of Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man. I wonder what new I might contribute; however, since I need to write a review of this Hugo winner to fulfill one of my other reading challenges, I’ll give this a shot as a pro and con list. This means that there will be spoilers. Be warned, if you have not read the book or want a more conventional review, choose one of the other reviews; they are good.

What I enjoyed:

1. The police procedural aspect.

I always thought that Asimov’s The Caves of Steel was the first detective science fiction novel. However, my research shows that Bester published a serial version of The Demolished Man beginning in January 1952 in Galaxy Science Fiction. Asimov’s serial of The Caves of Steel appeared in the same magazine in October to December 1953. These dates—in one sense—call into question the famous Asimov anecdote that he wrote The Caves of Steel to prove wrong John W. Campbell’s claim that mystery and science fiction were incompatible. If Campbell had been reading his competition’s magazine, then he would have seen that the feat had already been accomplished.

2. The cat-and-mouse game.

The machinations between murderer Ben Reich and detective Lincoln Powell are interesting to read. To be fair to Campbell, The Demolished Man is a police procedural, but it is not a whodunit, which was probably the type of mystery Campbell was referring to. The Demolished Man is a whydunnit, in that we know from early in the book who will be murdered, who will murder him and how the murder will be accomplished. The motive is murkier, and the denouement finally brings clarity to Ben Reich’s motives. Bester is at his best when he is illuminating the chess moves between Reich and Powell, as Powell tries to uncover means, motive and opportunity, and they both use their considerable syndicates to cherchez la femme, Barbara D’Courtney, the witness to the murder. My favorite piece of writing comes through Bester’s description of this:

Like an anatomical chart of the blood system, colored red for arteries and blue for veins, the underworld and overworld spread their networks. From Guild headquarters the word passed to instructors and students, to their families, to their friends, to their friends’ friends, to casual acquaintances, to strangers met in business. From Quizzard’s Casino the word was passed from croupier to gamblers, to confidence men, to the heavy racketeers, to the light thieves, to hustlers, steerers, and suckers, to the shadowy fringe of the semi-crook and near-honest. (107)

3. Style and Tone.

Style: Postmodern.

When I read Karel Capek’s War with the Newts (1936), I was very surprised that a novel written that early in the twentieth century used postmodern storytelling techniques. It was a pastiche of narrative, academic reports and newspaper clippings. I should have learned my lesson, but I was still surprised by Bester’s use of textual embellishments and linguistic play. He traces the telepathic conversations of the espers through patterns of language, such as spiderwebs, columns, and other abstract designs. I wish that I could reproduce one here. You’ll just have to read the book. Some of his characters’ names emerge through playing with the sounds of symbols, such as @kins, Wyg&, and ¼maine. Bester coins new words and invents slang that always reminds us that we are in a different time and place.

Tone: Hardboiled.

Both protagonist and antagonist have a hard-boiled edge worthy of Hammett or Chandler. Linc Powell’s address to a room full of suspects demonstrates this:

“He paused and lit a cigarette. ‘You all know, of course, I’m a peeper. Probably this fact has alarmed some of you. You imagine that I’m standing here like some mind-peeping monster, probing your mental plumbing. Well… Jo ¼maine wouldn’t let me if I could. And frankly, if I could, I wouldn’t be standing here, I’d be standing on the throne of the universe practically indistinguishable from God. I notice that none of you have commented on that resemblance so far…’” (76).

Also, much of the setting sounds like it is straight from the pen of Raymond Chandler:

Quizzard’s Casino had been cleaned and polished during the afternoon break… the only break in a gambler’s day. The EO and Roulette tables were brushed, the Birdcage sparkled, the Hazard and Bank Crap boards gleamed green and white. In crystal globes, the ivory dice glistened like sugar cubes. On the cashier’s desk, sovereigns, the standard coin of gambling and the underworld, were racked in tempting stacks. Ben Reich sat at the billiard table with Jerry Church and Keno Quizzard, the blind croupier. Quizzard was a giant pulp-like man, fat, with flaming red beard, dead white skin, and malevolent dead white eyes. (94)

A blind, albino croupier. I’m surprised Chandler did not think of him first.

The aspects of The Demolished Man that I liked demonstrate a universalism of tone, style and genre(s) that transcends the time in which the book was written. The aspects that I didn’t enjoy as much relate much more to the date of the book’s creation.

What I didn’t like:

1. Freud.

This book could not have been written without Freudian psychology. The concept of the conscious and unconscious is the basis of Bester’s culture and therefore intrinsic to the book. The espers’ telepathic abilities enable them to probe others’ unconscious thoughts and desires. This facet of Freudian psychology works well and does hold up over time. The Oedipus and Electra Complexes that form other important parts of the plot do not hold up as well and seem clunky in their use. For example, the regressing of Barbara D’Courtney to an infantile mental state so that she can fall in love with her new “daddy,” Linc Powell, seems silly to me:

“’Hello, Papa. I had a bad dream.’

‘I know, baby. I had to give it to you. It was an experiment on that big oaf.’

‘Gimme a kiss.’

He kissed her forehead. ‘You’re growing up fast,’ he smiled. You were just baby talking yesterday.’

‘I’m growing up because you promised to wait for me.’

‘It’s a promise, Barbara.’” (189)

This Electra Complex contributes another theme in the book that I disliked which is the portrayal of women.

2. The portrayal of women.

There are several stereotypical female characters in this book: the madam, the amoral society woman, the smart girl, and the damsel in distress. The two I want to discuss are Mary Noyes, the smart, capable friend of Powell and Barbara D’Courtney, the blonde damsel in distress, who spends most of the book as either an absent object of desire or a grown woman with the mind of a child. Of course, Mary is in love with Linc, and he depends on her for moral and personal support, but he will never love her because she is too smart, too capable; in short, she does not need a “daddy.”

Barbara D’Courtney witnesses her father’s murder and runs away. Reich and Powell search for her though much of the book, and when Powell finds her she can only relive the trauma of her father’s murder. She is then regressed to her infantile stage to heal her. Throughout the book, the reader never sees her make a decision, and she never speaks as an independent being. Lincoln falls in love with a baby in a woman’s body. She, on the other hand, as a victim of the Electra Complex, has no choice but to bond with her daddy. Bester’s Barbara pales in comparison with the women that appear in hard boiled novels, which in and of themselves are not famous for creating positive female role models. At least the femme fatales in Cain, Chandler, and Hammett are tough, strong and get to say some snappy dialogue.

Barbara D’Courtney witnesses her father’s murder and runs away. Reich and Powell search for her though much of the book, and when Powell finds her she can only relive the trauma of her father’s murder. She is then regressed to her infantile stage to heal her. Throughout the book, the reader never sees her make a decision, and she never speaks as an independent being. Lincoln falls in love with a baby in a woman’s body. She, on the other hand, as a victim of the Electra Complex, has no choice but to bond with her daddy. Bester’s Barbara pales in comparison with the women that appear in hard boiled novels, which in and of themselves are not famous for creating positive female role models. At least the femme fatales in Cain, Chandler, and Hammett are tough, strong and get to say some snappy dialogue.

Conclusion:

The Demolished Man is certainly worth the read and not just for its “legacy value.” However, I would like to end with Harry Harrison’s discussion of its legacy:

“This kind of novel had never happened before. Other writers have since used and built upon its structure: Blish, Zelazny, and Delany come to mind. The New Wave mined its assets, and the cyberpunks echo only dim whispers of The Demolished Man’s rolling thunder. But Bester came first—and is still the master.” (From the Introduction, viii-ix).

GMRC Review: Virtual Unrealities by Alfred Bester

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed.

Alfred Bester is one writer who kind of did it all during his lifetime: science fiction, mainstream magazines, comics, television, stage, film etc., etc. In the SF community he is best known for his two novels The Demolished Man (which won the first Hugo award in 1953) and the equally dazzling The Stars My Destination (1956), both of which are amazing works that should be a part of everyone’s SF reading list. Amazing though they are, they certainly show their age. Bester did his best work in SF during the 1950s, while short fiction was still the lifeblood of the form, authors were paid by the word, and now-tired cliches were pursued with unabashed glee. The 1950s produced some great SF, to be sure, but it also produced drek that is perhaps best consumed as the target of lampooning in an episode of MST3K. Virtual Unrealities is a collection of Bester’s short work, which runs the gamut between amazingly engaging and…uh… not. Bester’s tendency to run between genius and drek is clearly outlined in Robert Silverberg’s essential introduction to the work, in which he includes a very telling quote from Damon Knight:

Alfred Bester is one writer who kind of did it all during his lifetime: science fiction, mainstream magazines, comics, television, stage, film etc., etc. In the SF community he is best known for his two novels The Demolished Man (which won the first Hugo award in 1953) and the equally dazzling The Stars My Destination (1956), both of which are amazing works that should be a part of everyone’s SF reading list. Amazing though they are, they certainly show their age. Bester did his best work in SF during the 1950s, while short fiction was still the lifeblood of the form, authors were paid by the word, and now-tired cliches were pursued with unabashed glee. The 1950s produced some great SF, to be sure, but it also produced drek that is perhaps best consumed as the target of lampooning in an episode of MST3K. Virtual Unrealities is a collection of Bester’s short work, which runs the gamut between amazingly engaging and…uh… not. Bester’s tendency to run between genius and drek is clearly outlined in Robert Silverberg’s essential introduction to the work, in which he includes a very telling quote from Damon Knight:

Dazzlement and enchantment are Bester’s methods. His stories never stand still a moment; they’re forever tilting into motion, veering, doubling back, firing off rockets to distract you…Bester’s science is all wrong, his characters are not characters but funny hats; but you never notice: he fires off a smoke bomb, climbs a ladder, leaps from a trapeze, plays three bars of “god Save the King,” swallows a sword and dives into three inches of water. Good heavens, what more do you want?

Knight hits the nail on the head here, and I really identified with his critique of Bester’s characters as merely funny hats. Most of his characters are placeholders, archetypes, and cardboard cutouts about as interesting as the paper they are printed on: they’re fairly flat, tend toward extremes, and demonstrate disturbing lack of incredulity given their situations. Take “Star Light, Star Bright” for example: when a man tells you he’s hunting for a family of missing geniuses who can defy the laws of physics and he is going to let you in on the money he can make exploiting them, you should at least make an honest effort at being skeptical before negotiating your share. Still, he can be lauded for the fact that his stories never stand still, and he plays the showman enough that, if you can run with him far enough to get where he wants you to go, there are some neat surprises in store (most of the time).

The Good, The Bad, The Psychotic, and the Overly-Credulous

Bester’s short fiction isn’t about hard science, rather it speculates about wild ideas taken to their extremes with some science thrown in (you know, for credibility’s sake). Given the loosey-goosey nature of the science, some of the stories almost read as contemporary fantasy, but I think of them closer as fantasies: extreme tales about desire, disappointment, frustration, anger, resentment, and high energy. I can imagine Bester as a showman in a flashy suit with a light-up tie clapping his hands together with a sharp, resounding crash as he leans in to a rapt audience and says “Ok, let’s see what you think of THIS one” before starting in frenetically with barely a breath between lines.

Of course, this frenetic energy meant that many of these stories are exhausting, and I found myself skipping around the book quite a bit as one story or another tried my endurance a mite too far. Each time I found myself skipping over the rest of a story because it drained me of energy (or interest), however, I would become instantly committed to another by the energy in its opening lines alone. For instance, I became utterly bored with the first story in the collection only to turn to the next (“Oddy and Id”) and be immediately sucked in by the first line: “This is the story of a monster.” When I became bogged down in the story “5,271,009,” I skipped ahead a bit and became immediately sucked in with the opener of his psychoanalytic gem “Fondly Fahrenheit”: “He doesn’t know which of us I am these days, but they know one truth. You must own nothing but yourself. You must make your own life, live your own life, and die your own death…or else you will die another’s.” This is really a testament to Bester’s ability to start a story at breakneck speed and use the resulting vortex to suck you into it.

While most of the stories in this collection begin with energy and intrigue you can feel on down to your toes, the endings vary in depth and overall effect. You can tell he’s trying to shoot the moon every time and end with pizazz. Bester’s not after a meditative hmmmm from his readers as he is a thunderous, involuntary AHA! or a long, ominous Oooohhh! Poe’s notion of “unity of effect” is applicable here. For Poe, all elements of a work of fiction should be unified in supporting the emotion or reaction that the author wants to elicit from the reader. Bester’s short work seems to exemplify unity of effect as all elements of these stories move towards a unified emotion or singular revelation in the climax. That there is really no denouement to speak of in Bester’s stories, which further indicates that the climactic AHA! moment is the point of the story. Sometimes this works out great, as in “Oddy and Id” where several scientists figure out that a young student of theirs has the power to make his unconscious desires come true. They struggle with whether or not to make the young man, Oddy, explicitly aware of this gift since until that point, while he was unaware of this gift, his actions have all been good. The climax of this story is one that stays with you for a while and works on your brain in intriguing ways, and it one of the best examples of Bester’s ability to dazzle in a conclusion.

In other works, however, the impact of that climactic moment or emotion is more akin to a fizzle than a bang. “Of Time and Third Avenue,” for example, is a predictable and ho-hum affair where a man from the future attempts to convince a man from the past to relinquish an almanac that would tell him what the future holds. The story is built around a revelation that, to my 21st century eyes at least, isn’t all that exciting and seems like it would have been overdone even at the time of its publication. That the man from the past demonstrated only the most token bit of incredulity regarding the possibility of time travel and an almanac from the future is typical Bester. He doesn’t have the time to thoroughly develop characters beyond “funny hats” or archetypes, so stories like this mean that you need to hold on to your suspension of disbelief with both hands as you read. “Star Light, Star Bright” was another fizzle for me. It slowly pulled me into an intriguing mystery involving a missing family of geniuses, but in the end it just didn’t have the payoff to make it worth the effort. The entire story felt retroactively deflated the moment I read its climax; one of those “awww, come on!” moments that make you feel silly for being invested in the plot in the first place. Bester is the consummate showman, and all of the stories in this collection are geared towards that big finish, although sometimes it fails to dazzle.

Where Bester seems to be in top form, and where his characterization is most compelling, is when writing about monsters: bad men who either make the choice to be bad or are helplessly compelled to do bad things. The protagonists of both The Demolished Man and The Stars My Destination are both wicked men (kill-your-family wicked, not fun-to-drink-with wicked), which is part of what makes them so appealing and so surprising for SF in the postwar era of the 1950s. Bester’s affinity for writing compelling monsters comes out in several stories in this collection. In “Fondly Fahrenheit” for example, a man who has never done a lick of work in his life finds himself relying on his family’s advanced, super-expensive android, and when that android ends up killing people his solution is to run away with it, as it is his only asset in the world, instead of reporting the incident and taking responsibility. “Pi Man” features a character who murders someone he likes and beats his own dog to death for no reason he can adequately explain to us or others (he’s at the whims of the cosmos), but by the end of the story even this monster is rendered sympathetic. Sometimes the compulsion or choice to do bad or evil things is funny (in the absurdist tradition), as in “The Man Who Murdered Mohammed” where a mad scientist finds his wife cheating on him and, instead of confronting her, he decides to build a time machine to go back in time and kill his wife’s mother (thereby wiping said wife out of existence) with…unexpected results. Sometimes it’s truly frightening, as in “Oddy and Id,” where we must conclude that the monster in the protagonist Oddy is no worse than the monster lurking in our own unconscious.

Where Bester seems to be in top form, and where his characterization is most compelling, is when writing about monsters: bad men who either make the choice to be bad or are helplessly compelled to do bad things. The protagonists of both The Demolished Man and The Stars My Destination are both wicked men (kill-your-family wicked, not fun-to-drink-with wicked), which is part of what makes them so appealing and so surprising for SF in the postwar era of the 1950s. Bester’s affinity for writing compelling monsters comes out in several stories in this collection. In “Fondly Fahrenheit” for example, a man who has never done a lick of work in his life finds himself relying on his family’s advanced, super-expensive android, and when that android ends up killing people his solution is to run away with it, as it is his only asset in the world, instead of reporting the incident and taking responsibility. “Pi Man” features a character who murders someone he likes and beats his own dog to death for no reason he can adequately explain to us or others (he’s at the whims of the cosmos), but by the end of the story even this monster is rendered sympathetic. Sometimes the compulsion or choice to do bad or evil things is funny (in the absurdist tradition), as in “The Man Who Murdered Mohammed” where a mad scientist finds his wife cheating on him and, instead of confronting her, he decides to build a time machine to go back in time and kill his wife’s mother (thereby wiping said wife out of existence) with…unexpected results. Sometimes it’s truly frightening, as in “Oddy and Id,” where we must conclude that the monster in the protagonist Oddy is no worse than the monster lurking in our own unconscious.

“Oddy and Id” is a good example of Bester’s fascination with psychology, particularly Freudian psychoanalysis, which played a pervasive role in his Hugo-award winning The Demolished Man. We could do strong Freduian readings of most stories in this collection, particularly “Time is the Traitor” which involves an investigation into the trauma of The Decider (no, not George Bush) who despite an almost prescient ability to predict the future (affecting the lives of billions and making him the richest, most powerful man ever) has the inexplicable compulsion to kill any and every man named Kruger that he comes across. While psychology has moved beyond Freud in many/most ways–which certainly doesn’t help the already-precarious way in which Bester’s work has aged–it nevertheless is appealing since it allows Bester to tap into and play with the unpredictable forces of the mind and make seemingly malevolent characters seem sympathetic and understandable to a degree. These characters visibly struggle with their desires, and those stories are where Bester’s characters are the closest to being actual characters instead of funny hats (funny like an over-the-top Derby hat).

I would also draw attention to another endearing bit of Bester’s experimentation: how he plays with the way words sit on the page. Occasionally he will often draw pictures using words that require you to read the page in a different way, to re-orient yourself to the story, or just to thumb you in the eye and defy your expectations. This was a pretty avant garde move for Bester in the 50′s and 60′s, predating the most experimental Language Poets (who also played with typeset and the form of words on the page) by at least a decade or two.

The Best of Bester?

In some ways, Bester was very much ahead of his time, and in others he was of it, which is one reason his fiction has dated pretty hard. If you know how to approach his work, however, you can look past its datedness (to a degree) and see the unbridled play going on underneath. It’s not without its problems, however. Virtual Unrealities is a collection that shows both sides of Bester: the frenetic genius and the trite, cliched stuff. Some of his stories are fun, others are haunting, and yet others have all the luster of a poorly-planned and poorly-timed joke. Silverberg, however, rightly notes in his forward that all of them–the good and the bad–are crackling with the energy, enthusiasm, and showmanship that was Bester’s hallmark. If you read this collection for the razzle and the dazzle, knowing in advance that it has aged hard and that he is shooting not for meditation but a unity of effect that privileges that AHA! moment at the end, then you too can have some fun with Virtual Unrealities, as I did.

GMRC Review: The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester

Jeremy Frantz (jfrantz) joined WWEnd at the beginning of Febuary and has quickly caught up on the Grand Master Reading Challenge. Jeremy reviews SF/F books on his blog The Hugo Endurance Project where he has given himself just 64 weeks to read every Hugo Award winner.

Jeremy Frantz (jfrantz) joined WWEnd at the beginning of Febuary and has quickly caught up on the Grand Master Reading Challenge. Jeremy reviews SF/F books on his blog The Hugo Endurance Project where he has given himself just 64 weeks to read every Hugo Award winner.

A few centuries from now, espers (Peepers, telepaths) have integrated into every level of society, making premeditated murder a thing of the past. How could someone harbor that kind of hatred when someone is liable to read your thoughts at any second? Enter Ben Reich, immensely wealthy and immensely disturbed but a “normal”. Reich plans to murder his business rival and take over his company and the galaxy, destroying the Esper Guild in the process.

Police Prefect Lincoln Powell is an esper and an insanely smart and adroit detective. Very early in his investigation he realizes that Reich is the criminal he’s after and sets about finding enough evidence for a conviction and sentence of “demolition”.

Sure, Freudian themes are all over the place in this book, and while that likely will float a lot of boats, I was drawn to the eugenics program devised by the Esper Guild. This is also what made me want to see Reich succeed, despite the fact that I was clearly supposed to hate him. In this world, Espers are seen as the pinnacle of human ability and the Esper Guild only allows espers to marry other espers in order to cultivate their unique skills. Moreover, even a world in which humanity has evolved to have integrated telepaths into every level of society and nearly transcended violence, it is a computer (Old Man Mose – good computer name right?) that must administer justice and “normals” are treated as nearly second-class citizens by the Espers. To me there is something deeply unsettling about what this society had to give up for their peace.

Reich’s crime though is an opportunity for “normals.” If Reich gets away with murder, and a normal is able to circumvent the infallible esper safety net, then a huge hole will have been punched in the fabric of this unfair system. The fact that Reich’s crime will likely make him the most powerful human in the galaxy would also mean an elevation of normal status. If Reich were unsuccessful and the good guys won, it could very possibly mean something dreadful for humanity and the title “The Demolished Man” takes on a wholly new meaning.

Indeed there were so many deeply layered themes in this book that I would think it would have had wider appeal over the years.

Melodrama

Most of the time, when you hear about melodrama it’s always in reference to theater or film but if there ever was a book exhibiting the same themes, it was The Demolished Man. When the book starts Ben Reich is clearly a monster, an insane, sad and absolute Mad Man. And not in a cool way. He is just sick and out of control and on the loose! As he is planning and committing D’Courtney’s murder, one cannot help but root for his failure. And yet, he is a truly captivating individual. It’s like watching a car wreck, you just can’t look away.

Powell is a 1st class esper and as such can delve into the deepest corners of the subconscious. He is an equally unstoppable force and the collision of these two gigantic personalities is really something to behold. He is an exceptionally skilled and exceptionally passionate police prefect and whenever Reich seems to (always) stay one step ahead, Powell is under tremendous pressure to devise some new scheme to trap Reich.

After the crime is committed, once Reich and Powell are desperately trying to locate the only witness, I found myself enjoying the competition so much that I literally could not take my eyes off the page (“Where is that damn girl!”). But this owes as much to the outrageous personalities of the two central figures as it does to the unique character of Bester’s prose.

A Graphic Novel

The narrative in The Demolished Man is primarily driven by Alfred Bester’s dialog, the pace and strength of which is both propelled to a fever pitch and readable by his superb use of space and symbols.

The narrative in The Demolished Man is primarily driven by Alfred Bester’s dialog, the pace and strength of which is both propelled to a fever pitch and readable by his superb use of space and symbols.

When espers stick to telepathic messages, they can communicate at lightning speed (I really like this idea and it reminded me of BrainPal communication from Old Man’s War by John Scalzi). If an esper conversation is at first disorienting, it is also immediately natural and his use of visual stimuli makes perfect sense in light of the fact that espers prefer to communicate by telepathic messages and symbols. I even questioned if Bester had taken this far enough. Why would espers limit themselves to sending images of text? In the end, I was happy to realize that with each conversation between a new pair of espers, or in new circumstances, the method of conversation would change. This seemed completely logical to me so I was okay with allowing myself to believe espers did things this way.

However, if at first an esper conversation is disorienting though, an esper party is nearly incomprehensible. Conversations become word art and combine with other conversations to create a web of thought patterns that is at once cool and psychosis inducing. The espers then play a game in which phrases and conversations take on multiple meanings; the literal meaning of the words, and also the meaning of the pictures those words create in the minds of the other espers. I believed it and liked it. A lot.

Throughout the book, visual embellishments of names and phrases like @tkins and ¼Maine, enhance the frenetic pace of the dialog, in my opinion. I found it an extraordinary tool for creating the experience of telepathic communication and throwing the reader into the mad dash that never ends. Though I was caught off-guard at first, once I realized you could read it like a txt message, it made complete sense and just felt right. If espers can communicate as fast as thought, why would they communicate with pictures as often as words? I actually started wondering if Bester had really gone far enough with it, considering how much communication has changed as a result of texts which are still much slower than the speed espers could communicate.

Recommendation

The quality of this book is evident by the fact that not only have the themes but also Bester’s unique style have remained relevant after almost 60 years. I think his fast pace owes to the fact that pop culture was really exploding at the time and is also what keeps this book relevant today. Being part science fiction, part detective/psychological thriller, this book also probably has appeal outside the genre, which is a dimension that few of the other Hugo Winners from the 1905’s can also claim. People, this is a good one.

GMRC Review: The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including this latest review for the GMRC.

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including this latest review for the GMRC.

Of the Grand Master authors, Alfred Bester may be the one with the shortest science fiction bibliography, encompassing only part of his writing career, which also included non-genre writing, radio and TV scripting (Tom Corbett: Space Cadet), comics (most notably Golden Age Green Lantern), magazine editing and book reviewing. He published a few stories between 1939 and 1942, made a semi-successful return to the field in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, but is remembered today almost entirely for two novels and not much more than a dozen stories published during the 1950s, comprising one of the most influential and well-regarded oeuvres in the field. His ‘50s writings have been seen as the bridge between the ‘40s Campbellian Golden Age and the more literate, experimental and socially conscious New Wave of the ‘60s, as well as a precursor of the ‘80s cyberpunk movement. The stories have been collected in Virtual Unrealities, while the novels are The Stars My Destination (1957) and The Demolished Man (1953, first serialized in Galaxy in 1952), which won the first Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1953.

Of the Grand Master authors, Alfred Bester may be the one with the shortest science fiction bibliography, encompassing only part of his writing career, which also included non-genre writing, radio and TV scripting (Tom Corbett: Space Cadet), comics (most notably Golden Age Green Lantern), magazine editing and book reviewing. He published a few stories between 1939 and 1942, made a semi-successful return to the field in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, but is remembered today almost entirely for two novels and not much more than a dozen stories published during the 1950s, comprising one of the most influential and well-regarded oeuvres in the field. His ‘50s writings have been seen as the bridge between the ‘40s Campbellian Golden Age and the more literate, experimental and socially conscious New Wave of the ‘60s, as well as a precursor of the ‘80s cyberpunk movement. The stories have been collected in Virtual Unrealities, while the novels are The Stars My Destination (1957) and The Demolished Man (1953, first serialized in Galaxy in 1952), which won the first Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1953.

Has any other author made such a large impact with so few stories? In the context of the time, it’s easy to see why The Demolished Man made such a strong impression. By the early ‘50s, newer writers (and some older ones) were looking to break with the traditions established by John W. Campbell’s Astounding during the ‘40s. Bester was among the authors who took advantage of the rise of F&SF and Galaxy, with their commitment to a more expansive view of what SF could be, to begin publishing stories that looked more towards psychology and sociology for inspiration, while Campbell continued to stress “hard science” and engineering. Along with this shift came an emphasis on more adult characterization within science fiction, openness to more “literary” approaches to the writing of SF, and an increasing appearance of social criticism and satire. These new trends crystallized in The Demolished Man, paving the way for writers like Dick, Sheckley, and eventually Delany and Gibson.

The Demolished Man is set at the beginning of the 24th century. Space flight is routine, and people live on several planets and moons throughout the solar system. Unlike his Golden Age forbears, Bester is uninterested in the nuts and bolts of how this is accomplished. There are no expositional pauses interrupting the breakneck pace of the novel. People travel between worlds as casually as we might catch a flight between cities. Instead of explaining this world, Bester immerses us in it. Within that framework, it would make no more sense to describe aspects not directly relevant to the story than for a writer mentioning a character’s trip downtown to describe how a car works, or how and when the transportation system was built. Instead, we get flashes of description, and the characters’ impressions, allowing us to slowly build the world in our minds:

“He passed through the steel portals of headquarters and stood for a moment on the steps gazing at the rain-swept streets… at the amusement center across the square, block after block blazing under a single mutual transparent dome… at the open shops lining the upper footways, all bustle and brilliance as the city’s night shopping began… the towering office buildings in the background great two-hundred story cubes… the lace tracery of skyways linking them together… the twinkling running lights of Jumpers bobbing up and down like a plague of crimson-eyed grasshoppers in a field…”

The story is fairly simple on the surface, and can be described as a science fiction murder mystery, in a future where crime is almost unheard of since the police are able to employ mind-reading “peepers” to prevent crimes before they happen, or ferret out actual criminals. Ben Reich, one of the most powerful industrialists in the solar system, determines to murder a rival who threatens his economic ascension, arrogantly plotting the crime (with the help of his Esper psychoanalyst) in a way that, even if the police can discover his role, they will be unable to prove. The amoral Reich is able to take advantage of the Esper Guild’s ethical code, which they have adopted in order to police themselves, while helping the rest of humanity in various capacities (for instance, as counselors and investigators), only intruding onto the thoughts of others under clearly specified circumstances, or with permission. Their goal is to train ever more people to become Espers, with the belief that humanity will eventually reach a new stage of harmonious coexistence once everyone achieves Esper powers. From their point of view, a person like Reich is especially dangerous to their cause, as they recognize that he is someone who has the potential to derail their plans through his own individual will to power. Despite being witnessed by the victim’s daughter, the murder plan is carried out, and Esper Detective Lincoln Powell quickly realizes that Reich is the murderer. The suspense, then, is not related to figuring out who the killer is, but rather derives from the cat-and-mouse game between Reich and Powell, as each tries to stay a step ahead of the other as Powell pieces together Reich’s plan in a search for evidence, and Reich looks for ways to throw him off the track or destroy the evidence before Powell can get to it. And, while we know who the murderer is from the start, it turns out that there is an aspect to the crime that is hidden even from Reich himself…

Without giving away the ending, this last mystery is related to Reich’s subconscious motivations. If there is an aspect to The Demolished Man that seems dated, it is the importance of Freudian psychology within the story. The rise of psychology as a science seemed to lead many SF writers of the ‘50s and ‘60s to extrapolate a future in which psychological science becomes similar to physical science in its ability to precisely understand, predict, and manipulate the human mind. The psychological experts in these stories can often understand individual motivations for people’s actions in a way that seems overly simplistic to modern readers. Much more interesting is Bester’s use of ESP in the story, and the way it is incorporated into the society portrayed in the novel. Some of the best passages are those that describe the thought processes of the “peepers.” In these sections, Bester experiments with typographical layout in order to better represent the difference between telepathic and verbal communication, and uses language that evokes the hyper-intensity of the mind-reading process:

Without giving away the ending, this last mystery is related to Reich’s subconscious motivations. If there is an aspect to The Demolished Man that seems dated, it is the importance of Freudian psychology within the story. The rise of psychology as a science seemed to lead many SF writers of the ‘50s and ‘60s to extrapolate a future in which psychological science becomes similar to physical science in its ability to precisely understand, predict, and manipulate the human mind. The psychological experts in these stories can often understand individual motivations for people’s actions in a way that seems overly simplistic to modern readers. Much more interesting is Bester’s use of ESP in the story, and the way it is incorporated into the society portrayed in the novel. Some of the best passages are those that describe the thought processes of the “peepers.” In these sections, Bester experiments with typographical layout in order to better represent the difference between telepathic and verbal communication, and uses language that evokes the hyper-intensity of the mind-reading process:

“Here were the somatic messages that fed the cauldron; cell reactions by the incredible billion, organic cries, the muted drone of muscletone, sensory sub-currents, blood-flow, the wavering superheterodyne of blood pH… all whirling and churning in the balancing pattern that formed the girl’s psyche. The never-ending make-and-break of synapses contributed to a crackling hail of complex rhythms. Packed in the changing interstices were broken images, half-symbols, partial references… The ionized nuclei of thought.”

This and the previous quote are good examples of Bester’s prose, which has been well-described as “crystalline” or “sharp.” The novel is characterized by very short, often fragmentary sentences or clauses. The effect is created of a relentless pace, with no wasted words. The reader is propelled forward obsessively, similarly to the characters of Reich and Powell, who cannot stop moving until they reach a resolution… To consider how this style might have seemed liberating or revelatory to readers at the time, read a chapter of The Demolished Man after a Heinlein or Asimov story from the ‘40s. It’s not that subsequent writers would imitate Bester’s hard-boiled style (though you might see Neuromancer in a new light after reading this novel), but rather that its success helped open up possibilities for SF writers to develop writing styles and tackle themes and types of stories that may not have seemed possible before.

I’ve tried to make a case in this review for Bester’s importance in the history of SF, but a review is supposed to help people decide whether they want to read a book. Even if you’re not interested in the historical context at all, The Demolished Man remains a startlingly modern, entertaining novel. It won’t seem as original to modern readers as it did sixty (!) years ago, of course, because its influence has been incorporated into countless subsequent works of science fiction, but Bester’s wonderful prose and skillful plotting still shines through, despite the outdated psychological aspects (admittedly used in an ingenious way) and some casual ‘50s sexism (why did mid-20th century male writers predict future societies that would be increasingly liberal in regard to sexuality, but pretty much completely miss out on the occupational and social gains that women would make?). For younger readers or those who haven’t read much older SF, I would think that the works of Alfred Bester would be an excellent place to start…

Recently Read Books in Brief

American Gods, by Neil Gaiman

American Gods, by Neil Gaiman

This is probably Gaiman’s most popular novel, and the 155 reads recorded from our members’ stats attests to that. I wish I could share their enthusiasm. While American Gods is certainly both competent and entertaining, I have enough problems with it that I simply don’t much care for it as a story. Gaiman’s prose style isn’t bad, though it is never great, and I would have liked something a little better for a story dealing with such high-minded ideas. But it is the ideas that are the problem, here. Gaiman has written about the survival of ancient, unworshipped gods before and since, especially in his Sandman series and in the later Anansi Boys. The big idea that he repeats in all these works is that gods are beings born out of the collective religious consciousness of a people, that they are phantasms which can exist only so long as they are worshipped, but who still possess what we would think of as godlike powers while they still live. This is hardly a dull idea, even if it is reheated Jungianism, and it’s not hard to see why it found such a large audience. Unfortunately, I simply cannot take Gaiman’s metaphysics seriously enough to enjoy the novel.

Even so, Gaiman imbues his story with some fine, human moments, and he even occasionally recalls his earlier skills as a horror writer. There’s a large section of the novel that takes place in an out-of-the-way town and which seems largely inconsequential to the story as a whole, despite a late attempt to tie it back into the main plot. The most entertaining part of the novel is that it makes you want to rummage through your Encyclopedia of Mythology to identify all the gods and demigods who appear (or you can use this cheatsheet, but where’s the fun in that?).

Not a bad read, but hard to take seriously, despite all its sound and fury. Might be worth reading as preparation for the upcoming HBO television adaptation.

The Demolished Man, by Alfred Bester

The Demolished Man, by Alfred Bester

Ben Reich is a man troubled by dreams, living in a world of telepaths. Much as in Minority Report, crime is difficult to commit and easy to punish, and murder is all but impossible. The future sees humanity expanding to other planets, but still crippled by its faults and flaws. Bester does a magnificent job creating the world of 2301, and his prowess as world-builder is even better here than in his celebrated The Stars My Destination. Unfortunately, his skills as a crime-drama writer are not as good.

It’s not much of a spoiler say that Reich commits murder, because he does so very early in the novel. While there is some suspense in the first part of the book, that largely disappears once the murder is done. There is a long cat-and-mouse chase between Reich and the police, but frankly the reader spends most of his time waiting for the police to laboriously put together all the pieces he already knows, and then has to wait even longer to see if the unlikeable Reich ever gets caught and punished for his crime. The only suspense in the book concerns the identity of The Man With No Face, a dream image that haunts Reich’s dreams, but it’s not a very interesting mystery.

The Demolished Man is worth reading if only for some very intriguing prose interpretations of what a telepath conversation might be like, but not for the murder mystery which is at its core.

Mistborn, by Brandon Sanderson

Mistborn, by Brandon Sanderson

I became familiar with Sanderson after he was chosen to finish Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series, so I decided to give his most popular trilogy a try. Mistborn is set in something like a post-apocalyptic Middle Earth—it’s a fantasy world where the evil god/wizard/warrior has won the battle against the chosen hero and remade the world in his own image. This is a magnificent idea, and Sanderson has a lot of fun with it in the first book of the trilogy. The resistance fighters are something like real-world revolutionaries, and are very much the underdogs. The group of heroes in here isn’t even the first to have attempted a revolution. This isn’t the kind of setup that would work apart from the larger body of genre fiction to play off of, but I expect it will be especially appreciated by those who have read fantasy for years.

Still, this isn’t a great series. Sanderson is a good writer, but I think he has a weakness when it comes to plotting. The first novel works as a whole, but the latter two are comparatively formless and sprawling. The trilogy ends in a very strange way, with an unfortunately literal deus ex machina. However, the alchemically-based system of magic is actually very detailed and precise in its functioning, something rare in fantasy literature, and much appreciated.

The first novel is decent, but it will make you want to read the follow-ups that fail to live up to the original.

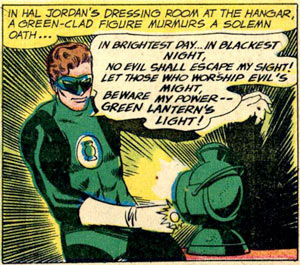

In Brightest Day

Many of us are anticipating the new Green Lantern movie coming out this summer. [10/24/2018 UPDATE: They’re still looking for a director for The Green Lantern Corp] What WWEnders may not know is the connection between award winning science fiction books and GL’s oath:

Many of us are anticipating the new Green Lantern movie coming out this summer. [10/24/2018 UPDATE: They’re still looking for a director for The Green Lantern Corp] What WWEnders may not know is the connection between award winning science fiction books and GL’s oath:

In brightest day, in blackest night

No evil shall escape my sight!

Let those who worship evil’s might

Beware my power — Green Lantern’s light!

From the iambic tetrameter, the metrical variation on the final line, and the nice caesura at the end, you might have guessed that the oath was a poem. I was surprised to learn, however, that it is credited to none other than Alfred Bester, the first Hugo winner (and thus, the first winner of any sci-fi award) ever.

On second, thought, I shouldn’t have been shocked. Short, pithy poems appear throughout Bester’s work. The Stars My Destination, published in 1956, finds its main character (Gully Foyle) floating in space, waxing philosophically:

Gully Foyle is my name

And Terra is my nation

Deep space is my dwelling place

And death’s my destination.

Later, the poem is repeated, with the final line changed, eponymously, to “The stars my destination.”

In an even earlier work, The Demolished Man, for which Bester won that first ever Hugo Award, the protagonist establishes a rule for living among mind-readers that is now a hallmark of science fiction. He recites a jingle designed to distract any ESPer from reading deeper thoughts:

Eight sir, seven sir, six sir, five sir,

Four sir, three sir, two sir, one.

Tenser, said the Tensor, Tenser said the Tensor.

Tension, apprehension, and dissension have begun.

Poetry, for Bester, has power. Whether it reveals the fate of a great man, blocks thoughts from psychic peeping Toms, or grants 24 hours of fantastic power to American test pilots, poetry actually does something in Bester’s worlds. Perhaps this explains those ubiquitous columns of poetry that appear in many pulp sci-fi magazines. If the words of science fiction are supposed to tell us what is to come, perhaps we should also believe that words, themselves, also have a future worth considering.

Full Details

Full Details