Month of Horrors: End of Month Wrap-Up

Today isn’t just Halloween, it’s also the closing day of WWEnd’s Month of Horrors, our 31-day celebration of the Horror genre in conjunction with adding this genre to the site. We’ve decided to wrap up the festivities with a dialogue between Rico and me about the genre. We may not be the biggest Horror aficionados in the world, but we both love literature, and I think we are both curious to see how it fits in the pantheon of genres, and especially how it relates to Science Fiction and Fantasy, the long-time staples of the WWEnd site.

Jonathan: Ward Shelley in his infographic links genre fiction back into the primal emotions of Fear and Wonder. Arguably the Horror genre is far more about Fear than Wonder, though it often has its fair share of both. H. P. Lovecraft, of all people, occasionally wrote lyrically beautiful stories like “The White Ship” which were filled with wonder. But despite its primal roots, I don’t know of any previous body of literature that has focused so intently on the emotion of fear. In some ways, it reminds me of amusement park rides, which are built almost entirely to give the riders a thrill or a scare, the false feeling that their lives are in imminent physical danger even though everything is perfectly under control. I’ve often wondered if the thrill of fear is the primary draw for horror readers, if they are wanting to feel a “safe danger” like that of the amusement park ride. In other cases I suspect that the genre is a way of dramatically expounding on a philosophical or theological belief about the nature of the universe, the human condition, and the relationship between humanity and whatever cosmic powers might be. Do you have any thoughts on the genre from this perspective? Certainly I doubt that we will be able to fully unravel the mystery of any genre’s attraction—even Science Fiction is often more confounding than captivating to me—but I admire it if only as an outsider.

Jonathan: Ward Shelley in his infographic links genre fiction back into the primal emotions of Fear and Wonder. Arguably the Horror genre is far more about Fear than Wonder, though it often has its fair share of both. H. P. Lovecraft, of all people, occasionally wrote lyrically beautiful stories like “The White Ship” which were filled with wonder. But despite its primal roots, I don’t know of any previous body of literature that has focused so intently on the emotion of fear. In some ways, it reminds me of amusement park rides, which are built almost entirely to give the riders a thrill or a scare, the false feeling that their lives are in imminent physical danger even though everything is perfectly under control. I’ve often wondered if the thrill of fear is the primary draw for horror readers, if they are wanting to feel a “safe danger” like that of the amusement park ride. In other cases I suspect that the genre is a way of dramatically expounding on a philosophical or theological belief about the nature of the universe, the human condition, and the relationship between humanity and whatever cosmic powers might be. Do you have any thoughts on the genre from this perspective? Certainly I doubt that we will be able to fully unravel the mystery of any genre’s attraction—even Science Fiction is often more confounding than captivating to me—but I admire it if only as an outsider.

Rico: Horror does seem to have older roots than other genres. Whether it’s Odysseus trapped between the monster (Scylla) and a gaping nothingness (Charybdis), Hercules battling a hydra, or Jason facing the harpies, even the ancient Greeks felt the need for monstrous yarns. Lovecraft said this was because fear is our oldest emotion, especially fear of the unknown. In a lot of ways, it sort of drives us to find out what it is that scares us, so we can conquer it. Fear, then, is not so different from wonder.

Rico: Horror does seem to have older roots than other genres. Whether it’s Odysseus trapped between the monster (Scylla) and a gaping nothingness (Charybdis), Hercules battling a hydra, or Jason facing the harpies, even the ancient Greeks felt the need for monstrous yarns. Lovecraft said this was because fear is our oldest emotion, especially fear of the unknown. In a lot of ways, it sort of drives us to find out what it is that scares us, so we can conquer it. Fear, then, is not so different from wonder.

As to why horror is so attractive, however, we need a different explanation. Maybe one clue can be found in physiology. Sartre once observed that the symptoms of fear (dilation of the pupils, elevated heart rate, perspiration) also happen to occur when one falls in love. Two completely different conditions elicit the same bodily reactions. Because fear is so primal, it might be easier to frighten a reader than to make him/her fall in love. If the trill of a good scare gets me flushed in a way that is so love-like, why wouldn’t I enjoy it?

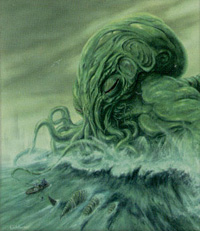

Jonathan: You mentioned both the Lovecraft and the ancient Greeks, but there’s a world of difference between the way each would approach a horrific tale. The Greeks had stories of monsters like Medusa and Typhon which, on the surface, are very similar to monsters like Lovecraft’s Cthulu, but while the Greek monsters might eat the occasional passerby and even level a mountain or two, Olympus could never truly lose the world to these monsters. Cthulu, on the other hand, will inevitably rise from the watery deeps to darken the sky and devour mankind. There’s the horror that is finite and destructible, like the Chimera and the Hydra, and then there’s the horror that devours not only people but hope. A classical tale of horror might end badly for some people, but it will also end with the sun still shining and regular people living their lives. A modern horror tale will often end with the emotional and psychological devastation of the protagonist, whose beliefs about the stability of the world have been crushed.

Jonathan: You mentioned both the Lovecraft and the ancient Greeks, but there’s a world of difference between the way each would approach a horrific tale. The Greeks had stories of monsters like Medusa and Typhon which, on the surface, are very similar to monsters like Lovecraft’s Cthulu, but while the Greek monsters might eat the occasional passerby and even level a mountain or two, Olympus could never truly lose the world to these monsters. Cthulu, on the other hand, will inevitably rise from the watery deeps to darken the sky and devour mankind. There’s the horror that is finite and destructible, like the Chimera and the Hydra, and then there’s the horror that devours not only people but hope. A classical tale of horror might end badly for some people, but it will also end with the sun still shining and regular people living their lives. A modern horror tale will often end with the emotional and psychological devastation of the protagonist, whose beliefs about the stability of the world have been crushed.

So while there is a kind of pleasurable (even love-like) thrill that can come from a frightening story, I don’t know that the Lovecraftian sort of total despair offers the same pleasure. David Hume once wrote about the stage tragedies of his day: “What [can be] so disagreeable as the dismal, gloomy, disastrous stories with which melancholy people entertain their companions?  The uneasy passion being there raised alone, unaccompanied with any spirit, genius, or eloquence, conveys a pure uneasiness, and is attended with nothing that can soften it into pleasure or satisfaction.” Do you think that modern horror perhaps offers the taste of that thrill without the pleasure, or am I being too harsh on it?

The uneasy passion being there raised alone, unaccompanied with any spirit, genius, or eloquence, conveys a pure uneasiness, and is attended with nothing that can soften it into pleasure or satisfaction.” Do you think that modern horror perhaps offers the taste of that thrill without the pleasure, or am I being too harsh on it?

Rico: I agree that there is a difference between the Greek stories and Lovecraft, but Lovecraft doesn’t define the genre. The world is still intact when the tell-tale heart stops beating, when the vampire finally gets staked, and when the last alien is flushed into space by Sigourney Weaver. Lovecraftian horror, it seems to me, is a special extremist sub genre. Of course, even it doesn’t find the world in tatters (there’d be no story if Hastur or Cthulu ever crossed over). It’s the threat of obliteration that makes the story exciting. In that sense, the Lovecraftian world really does share something in common with Odysseus and his men hovering on the brink of Charybdis, yet not quite falling in.

Also, although it’s true that the Olympic gods may not lose the world (well, there is one time, in the Iliad, when the Fates tell Zeus that he may defy them to save Troy, but that the cosmos would fall into chaos as a result), but humans certainly can lose their world. I’m thinking of Hecuba, for whom there can be no solace. Niobi (“all tears”) comes to mind. As in Lovecraft’s world, the gods take away everything.

Perhaps a better ancient analogue to Cthulu is Vishnu, the Hindu god whom Oppenheimer quoted as he reflected upon the nuclear horror he helped to create: “Now, I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

Perhaps a better ancient analogue to Cthulu is Vishnu, the Hindu god whom Oppenheimer quoted as he reflected upon the nuclear horror he helped to create: “Now, I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

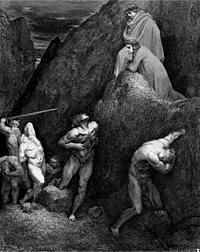

Jonathan: Fair enough. In addition to the classical and modern horror narratives, it’s educational to look at the Medieval/Christian stories that most closely match the genre. Medieval poets loved singing about bizarrely chimeric beasts in addition to the demons and occult practitioners who frequently tormented the innocent. Meanwhile, Dante’s Inferno explored the greatest horror imaginable: everlasting damnation and torment. It’s a particularly interesting sort of horror, though, in that the one experiencing its pains has brought them upon himself. (Those in Dante’s version of Hell who are there by no vice of their own, like the unbaptized infants and the virtuous pagans, suffer no external pains.) When Dante tours the underworld, he is not witnessing the caprices of a cruel god, but the wasted lives of those who refused to do good and now suffer the consequences. The Medieval vision of Hell managed to combine the classical vision of celestial permanence and beauty with the all-consuming despair of a Lovecraftian apocalypse, as it’s inscribed on Hell’s doors: “Justice caused my high Architect to move… / The highest Wisdom, and the primal Love … / Abandon all hope you who enter here” (trans. Anthony Esolen).

To my mind, the best of the Horror genre is that which manages to keep both aspects of reality in play. When the balance tips entirely towards Tragedy (so to speak) or entirely in favor of Comedy, one feels that the poet or novelist isn’t being entirely honest about the way things are. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is a magnificently-written novel, but it is arguably stuck in an emotional rut of bleak despair. As a counterpoint, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings saga is a work which manages to drink the cup of futility to its last drop, without losing hope.

To my mind, the best of the Horror genre is that which manages to keep both aspects of reality in play. When the balance tips entirely towards Tragedy (so to speak) or entirely in favor of Comedy, one feels that the poet or novelist isn’t being entirely honest about the way things are. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is a magnificently-written novel, but it is arguably stuck in an emotional rut of bleak despair. As a counterpoint, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings saga is a work which manages to drink the cup of futility to its last drop, without losing hope.

Rich: That, it seems, is very much in keeping with Hallowe’en, which is a sort of twilight between the despair of loss (death) and the joy of All Saints Day (and All Souls Day, on November 2). The fact that today is an ’eve (and not the day itself) suggests a sort of lack of completion. We go out begging (trick or treating), perhaps because we lack something we want. All Hallows Evening is a darker anticipation of something miraculous, the feast day of every saint that ever was. There is, nay, there must be some sort of hope at the end of despair.

Jonathan: I’ll close simply by noting a small handful of Horror books I still plan to read, since I still feel inadequately-read in the genre. The Monk, The Castle of Otranto, and Melmoth the Wanderer are all at the top of my list as Gothic subgenre works; despite my recent bad experience with Nathaniel Hawthorne’s attempt at Gothic fiction, I still want to give it a try. I might also crack open some children’s horror with Neil Gaiman’s Coraline and The Graveyard Book. Joe Hill’s Horns is on the list, but a little further down.

What say you, Rico?

Rico: I’m likely to be more behind in my reading than you. It seems that much of the horror tradition is American, and may have roots not just in the English Gothic Novel, but also in the constant low-grade terror of North America’s indigenous population. Jung believed that tales of demonic possession waned in the American mind as rationalism took hold, and was replaced by stories of Indian abductions (and that those stories, in the 20th century turned into alien abductions!). This gets back to your idea of the unknown, and it makes me want to read all three kinds of "abduction" stories. The stories of Captain John Smith may sound more like a good old adventure story than horror, but it was a source of much anxiety to its readers in early America, who were more than familiar with the gruesome legacy of Roanoke. I also have an interest in the more recent accounts of body snatching: One such story is The Exorcist, which William Peter Blatty did not intend to be a horror novel at all. Another is I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, which has inspired how many movies? If Jung were writing today, he might say that zombies are the latest incarnation of the abduction myth, and boy is it having its heyday, today.

Rico: I’m likely to be more behind in my reading than you. It seems that much of the horror tradition is American, and may have roots not just in the English Gothic Novel, but also in the constant low-grade terror of North America’s indigenous population. Jung believed that tales of demonic possession waned in the American mind as rationalism took hold, and was replaced by stories of Indian abductions (and that those stories, in the 20th century turned into alien abductions!). This gets back to your idea of the unknown, and it makes me want to read all three kinds of "abduction" stories. The stories of Captain John Smith may sound more like a good old adventure story than horror, but it was a source of much anxiety to its readers in early America, who were more than familiar with the gruesome legacy of Roanoke. I also have an interest in the more recent accounts of body snatching: One such story is The Exorcist, which William Peter Blatty did not intend to be a horror novel at all. Another is I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, which has inspired how many movies? If Jung were writing today, he might say that zombies are the latest incarnation of the abduction myth, and boy is it having its heyday, today.

So that wraps up our Worlds Without End Month of Horrors! We hope you’ve all enjoyed our exploration of the Horror genre during the month of October. Cheery chills, and safe trick-or-treating!

Month of Horrors: The Road

Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road made some big waves when it was promoted through Oprah’s book club back in 2007. This led to an awkward interview on her talk show—McCarthy is notorious for avoiding any and all interviews—but it did wonders for his book sales. It’s fascinating that such a dark tale would be promoted in what can accurately be described as a pop venue, but I’m sure Cormac got some laughs knowing that his story of a man and his son desperately trying to survive in a post-apocalyptic wasteland would be read by housewives around the country.

Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road made some big waves when it was promoted through Oprah’s book club back in 2007. This led to an awkward interview on her talk show—McCarthy is notorious for avoiding any and all interviews—but it did wonders for his book sales. It’s fascinating that such a dark tale would be promoted in what can accurately be described as a pop venue, but I’m sure Cormac got some laughs knowing that his story of a man and his son desperately trying to survive in a post-apocalyptic wasteland would be read by housewives around the country.

This drearily violent tale follows an unnamed man who is traveling to the ocean with his son (called only “the boy” by the author) across a land wasted by some unspecified disaster. At one point it’s suggested that this is a nuclear winter, but McCarthy leaves the cause of the earth’s death throes as unnamed as his protagonists. Realizing that they will not survive another winter at their current latitude, the father believes that moving south toward the ocean will bring some relief, and possibly better company than the roving gangs of thieves and cannibals they currently have to deal with at every turn.

McCarthy doubles down on the horror first by taking a hard, long look at the devastation that’s been brought down on the earth. There is little to no greenery left, nor any wildlife, and ash falls from the sky intermixed with snow. Just about the only food left is what can be scavenged from canned food stores, which leads to the second aspect of The Road’s horror, the cannibals. Those who are not strong enough to physically protect themselves are often taken alive to be eaten gradually, or else are used to, shall we say, generate more food.

McCarthy doubles down on the horror first by taking a hard, long look at the devastation that’s been brought down on the earth. There is little to no greenery left, nor any wildlife, and ash falls from the sky intermixed with snow. Just about the only food left is what can be scavenged from canned food stores, which leads to the second aspect of The Road’s horror, the cannibals. Those who are not strong enough to physically protect themselves are often taken alive to be eaten gradually, or else are used to, shall we say, generate more food.

The man and the boy wind their way through one horror after another in search of their goal, each horror more emotionally scarring than the last. At one point they are walking down a stretch of the road that had been melted by surrounding forest fires during the first days of the earth’s scorching. “The blacktop underneath had buckled in the heat and then set back again,” as McCarthy describes it. He goes on,

Boxes and bags. Everything melted and black. Old plastic suitcases curled shapeless in the heat. Here and there the imprint of things wrested out of the tar by scavengers. A mile on and they began to come upon the dead. Figures half mired in the blacktop, clutching themselves, mouths howling. He put his hand on the boy’s shoulder. Take my hand, he said. I dont think you should see this.

What you put in your head is there forever?

Yes.

It’s okay Papa.

It’s okay?

They’re already there.

I dont want you to look.

They’ll still be there.

He stopped and leaned on the cart. He looked down the road and he looked at the boy. So strangely untroubled.

Why dont we just go on, the boy said.

Yes. Okay.

They were trying to get away werent they Papa?

Yes. They were.

Why didnt they leave the road?

They couldnt. Everything was on fire.

They picked their way among the mummied figures. The black skin stretched upon their bones and their faces split and shrunken on their skulls. Like victims of some ghastly envacuuming. Passing them in silence down that silent corridor through the drifting ash where they struggled forever in the road’s cold coagulate.

I didn’t sleep well the night after finishing this novel.

(Image from stock.xchng, by Mario Alberto Magallanes Trejo.)

What a Long, Strange Trip It’s Been

If I asked you to name the most important science fiction film of 2009, what would you answer?

If I asked you to name the most important science fiction film of 2009, what would you answer?

Moon? District 9? Avatar?

Tough question, I know. Each has, in its way, something worthy to advocate for the title of 2009’s most significant genre film.

In a year loaded with sci fi pictures (such as Star Trek, Watchmen, Pandorum, Terminator Salvation, 2012, Gamer, Surrogates, and on and on), it’s the ones that truly drive toward a real, authentic human story that stay with us the most, especially Moon and District 9.

But for my money, the answer is not the personal tragedy of Moon. Or the social commentary of District 9. Or the grand spectacle of Avatar.

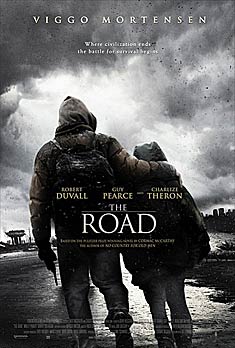

The most deeply felt and important science fiction film of 2009 is simply The Road.

If you’re not familiar with The Road, it stars Viggo Mortensen as a father who, along with his ten year old son, is travelling through the post-apocalypse wasteland that was once America in an effort to head south toward the futile hope for greener pastures. In this grim landscape where all the animals and vegetation have died off (as well as most of human civilization – at least, the better parts), Viggo and the boy contend with the constant specter of starvation and roving bands of cannibals.

Alright, I know the word “apocalypse” probably caught your eye (and I’m sure “cannibals” didn’t go unnoticed, either), and you likely already started forming some opinions. Let me stop you in your tracks. This is not The Road Warrior. Or A Boy and His Dog. Or any of the other dozen or so apocalyptic wasteland films that might jump to mind.

The Road is something completely and entirely different.

I’ve seen some reviews that spoke of The Road’s echoes of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and with the ashen landscape that Viggo (aka The Man) and his son The Boy are immersed in, it’s easy to see that. And I believe I saw at least one review where Albert Camus was mentioned, and I had already myself come to the conclusion that The Plague could be a possible kindred spirit. But in considering The Road for a few days now, I think the closest literary equivalent for the film (besides its own Cormac McCarthy source material of the same name) would have to be Elie Wiesel’s Night.

Night is of course Wiesel’s famous memoir of his and his father Shlomo’s decent into the hell of Auschwitz – the journey of a father and son fording a wasteland, beset on all sides by extreme human depravity.

I see The Road as a photographic negative of Night – in Night, the story is told from the son’s point of view. In The Road, it is told from the father’s. In both cases, the protagonist ties his meager hope for retaining a sense of humanity amidst the direst conditions imaginable through the constant action of trying to salvage the life of a loved one.

In both narratives, the most intimate of human relationships – that of a parent and a child, the wellspring of future hope and promise – is set in direct opposition to a panorama of agony and negation. The landscapes our heroes traverse are populated with monsters who happen to be people – not aliens or zombies or whatever – just people.

One scene in The Road confirmed this for me. Viggo and the boy narrowly escape a country estate where a group of cannibals has taken up homestead. The camera zooms in on the cannibals as they come out on their porch, looking to the nearby woods for any sign of the escapees. And the most remarkable thing – the cannibals look exactly like you. And like me. Not particularly weird or freaky. Not Leatherface or what have you. Regular people.

John Hillcoat (the film’s director) seemed to be making the point, “Yes, they’re just folks.”

(I seem to recall reading something about George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead where Romero said that the reason his zombies were so scary is that they were your neighbors. Too true.)

The resounding brutality of Night and The Road germinates from within the human heart and its failure, on a massive scale, to love its fellow human being. On these stages, the parent-child bond is all the more poignant and amplified when set in counterpoint.

In such worlds where everything is grief and suffering and despair, the question is not would you die for your loved one, but rather would you live for them? In The Road the Boy becomes his father’s sole reason for living, and the tenderness and love with which the father struggles to keep his son alive in so harsh a reality is what drives the film. The most heroic act that Viggo performs in the film is to love his son. The best stories are not about “out there” but rather about “in here,” and that is why I think The Road is the most significant genre film of 2009.

In such worlds where everything is grief and suffering and despair, the question is not would you die for your loved one, but rather would you live for them? In The Road the Boy becomes his father’s sole reason for living, and the tenderness and love with which the father struggles to keep his son alive in so harsh a reality is what drives the film. The most heroic act that Viggo performs in the film is to love his son. The best stories are not about “out there” but rather about “in here,” and that is why I think The Road is the most significant genre film of 2009.

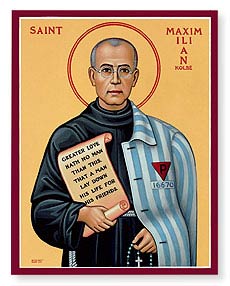

As an aside, and not at all by my own design, I started writing this piece last Sunday, which was the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the most famous parent in the history of mankind. It so happened that on that day, my wife shared with me a daily reflection written by St. Maximilian Kolbe, a Catholic priest and great devotee of Our Lady who famously gave his life in Auschwitz so as to spare the life of a fellow prisoner. (The prisoner, a husband and father of two, had cried out for his family when he was chosen to be executed, prompting St. Kolbe to successfully petition to take his place in the death chamber.)

In the daily reflection taken from an essay that St. Kolbe had written before the war, he remarked, “… the love of parents towards their children is superior to any other love.” I share this anecdote because the coincidence of his remark being shared with me on Mary’s Feast day when I contemplated the parental love of The Road (and recalled the heartbreaking witness of Night)is too strong not to share it.

Full Details

Full Details