Outside the Norm: Dubravka Ugresic’s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

I began this Outside the Norm blog because I wanted to challenge myself to read more books by women, persons of color and nationalities other than American and British. So far I’ve read canonical authors like Le Guin and those who are starting to make a name in the F and SF world like Nnedi Okorafor. I’m also beginning to see this title as a license to write about others whose speculative work is just outside the parameters of the lists and awards compiled here. This blog is about one of those books, Dubravka Ugresic‘s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg.

This book first came to my attention because it won the 2010 James Tiptree, Jr. Award. The Tiptree’s mission, as stated on its website, is to honor a science fiction or fantasy work "that expands or explores our understanding of gender" and is given each year at WisCon. Ugresic is a Croatian academic who was forced into exile by a nationalist government. Most of her books and collections of essays are political in nature. This book was nominated for the Man Booker International Prize, so, as you can see, she’s not an author whose name would typically end up on a list of the year’s best fantasy writers. Yet, her use of myth in this book placed the book in the realm of fantasy for some readers like the Tiptree jury. The book is a three-part engagement with Baba Yaga, the witch-like character of Slavic folklore.

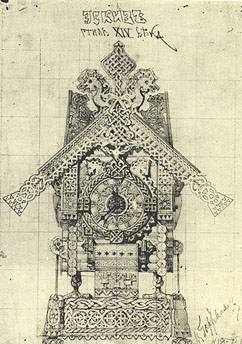

I confess that all I really knew about Baba Yaga came through an introduction via the prog rock CD Pictures at an Exhibition (1972) by Emerson, Lake and Palmer. That group had recorded a suite by the Russian composer, Modest Mussorgsky, which Mussorgsky had based on an art exhibition by the Russian artist Viktor Hartmann. (For more about Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, check out the music and new images here.) One of the images that inspired subsequent songs by Mussorgsky and Emerson, Lake, and Palmer was "The Hut of Baba Yaga." This song sent my younger self off to research Baba Yaga.  I learned that Baba Yaga lived in a giant hut that walked around on huge chicken legs. Much like the witches in Grimm’s fairy tales, she lured children to her forest hut and ate them. She flew around in a mortar, using the pestle like an oar, and used a broom to sweep away her tracks. Here you can see her connection to the more western witches on broomsticks. However, no previous knowledge of Baba Yaga is required to read this book because the reader is slowly educated through the author’s three sections. This structure and strategy is what makes this book so interesting and made me decide to write this review.

I learned that Baba Yaga lived in a giant hut that walked around on huge chicken legs. Much like the witches in Grimm’s fairy tales, she lured children to her forest hut and ate them. She flew around in a mortar, using the pestle like an oar, and used a broom to sweep away her tracks. Here you can see her connection to the more western witches on broomsticks. However, no previous knowledge of Baba Yaga is required to read this book because the reader is slowly educated through the author’s three sections. This structure and strategy is what makes this book so interesting and made me decide to write this review.

The short prologue "At First You Don’t See Them…" unapologetically tells the reader that this book will be about old women:

Sweet little old ladies. At first you don’t see them. And then, there they are, on the tram, at the post office, in the shop, at the doctor’s surgery, on the street, there is one, there is another, there is a fourth over there, a fifth, a sixth, how could there be so many of them all at once? (2)

The invisibility of these "little old ladies" is a direct comment on society’s tendency to dismiss the elderly and their needs and forget about their continued usefulness to society. Ugresic’s book goes beyond this generalization of invisibility and takes on the ways that our view of "little old ladies" is often based on gender stereotypes created by earlier patriarchal societies, especially crone figures like the Baba Yaga.

The first section "Go There – I Know Not Where – and Bring Me Back a Thing I Lack" has no speculative fiction elements. It is written in the first person. The narrator is a famous author who frequently returns to her hometown of Zagreb, Croatia to take care of her elderly mother. Her widowed mother has had a stroke: she uses a walker and her language was affected so that she often uses the wrong word. This leads to some humorous conversations between mother and daughter:

The first section "Go There – I Know Not Where – and Bring Me Back a Thing I Lack" has no speculative fiction elements. It is written in the first person. The narrator is a famous author who frequently returns to her hometown of Zagreb, Croatia to take care of her elderly mother. Her widowed mother has had a stroke: she uses a walker and her language was affected so that she often uses the wrong word. This leads to some humorous conversations between mother and daughter:

"Bring me the…."

"What?"

"That stuff you spread on bread."

"Margarine?"

"No."

"Butter?"

"You know it’s been years since I used butter!"

"Well, what then?"

She scowls, her rage mounting at her own helplessness. And then she slyly switches to attack mode.

"Some daughter if you can’t remember the bread spread stuff!"

"Spread? Cheese spread?"

"That’s right, the white stuff," she says, offended, as if she had resolved never to again utter the words ‘cheese spread.’" (11)

I think my favorite one is when she asked for "the biscuits, the congested ones," instead of the digestive ones. (11-12)

We learn that the mother is Bulgarian and came to Croatia as a young wife. Some of her most treasured curios represent Bulgaria or are mementos of her early life. The daughter decides that she wants to visit Bulgaria as her mother’s bedel: "[c]enturies ago the wealthy would send someone else off on the hajj or the army in their stead as a bedel, a paid surrogate" (41). The daughter wants to bring back pictures of her mother’s city so that her mother can remember her youth. She enlists the help of a Bulgarian fan, Aba, who had written the author earlier, wanting to visit her in Croatia. Aba, a student in folklore, was in Croatia on an academic fellowship. The author was unable to meet Aba but facilitated a relationship between her mother and Aba, as fellow Bulgarians. The mother and Aba hit it off, so the daughter later arranges for Aba to accompany her while in Bulgaria. Her best-laid plans of "bedelship" go astray: she finds her mother’s hometown a victim of the communist and post-communist economies and finds the locations of her mother’s home and school changed and worn down; she also finds Aba annoying because the young fan wants to quote the author’s writing back to her. Thus, this first section is a look at aging, relationships and post-communist Eastern Europe.

We learn that the mother is Bulgarian and came to Croatia as a young wife. Some of her most treasured curios represent Bulgaria or are mementos of her early life. The daughter decides that she wants to visit Bulgaria as her mother’s bedel: "[c]enturies ago the wealthy would send someone else off on the hajj or the army in their stead as a bedel, a paid surrogate" (41). The daughter wants to bring back pictures of her mother’s city so that her mother can remember her youth. She enlists the help of a Bulgarian fan, Aba, who had written the author earlier, wanting to visit her in Croatia. Aba, a student in folklore, was in Croatia on an academic fellowship. The author was unable to meet Aba but facilitated a relationship between her mother and Aba, as fellow Bulgarians. The mother and Aba hit it off, so the daughter later arranges for Aba to accompany her while in Bulgaria. Her best-laid plans of "bedelship" go astray: she finds her mother’s hometown a victim of the communist and post-communist economies and finds the locations of her mother’s home and school changed and worn down; she also finds Aba annoying because the young fan wants to quote the author’s writing back to her. Thus, this first section is a look at aging, relationships and post-communist Eastern Europe.

The second section, "Ask Me No Questions and I’ll Tell You No Lies," continues the theme of playing with language that Ugresic began in the first section. One character, Beba, says the wrong word when nervous which leads her to say things like "Have a nice lay," when she means to say "Have a nice day." This playfulness continues throughout section two whose genre is closest to magical realism. It is full of improbable happenings and unbelievable coincidences that the characters never seem to notice. Also all the characters seem more symbolic and less real. Each seems like an archetype for an idea that I don’t quite grasp. (This is not a criticism. I didn’t feel lost at all.)

In this section, three old Croatian ladies, Pupa, Kukla, and Beba, ranging in age from sixty to eighty (or maybe more), visit the Wellness Centre, a spa in the Czech Republic. Their only connection to section one is that Pupa is mentioned there as one of the mother’s friends. Most of the men that the women meet in this section are part of the beauty and anti-aging industry. Mr. Shaker is an American who owns a business that sells pills, potions, and remedies, "bearing the food label supplement" (92). His American market is collapsing because reports are emerging that his remedies "pump up muscles" but "reduced potency" (93). So now he is looking into the "post-communist market" (93). Dr. Topolanek, the owner of the Wellness Centre, makes his living via "human vanity," selling his theory of longevity as well as spa treatments and massages (98). Finally, the old women meet Mevludin, a young Bosnian refugee, who works as a masseur at the Centre. The women spend a fantastic six days at the Centre. The endings are "happy" for Pupa, Kukla, and Beba, but they each travel from the spa into unknown worlds and challenges.

Here Ugresic criticizes the cult of youth and beauty. Her Croatian perspective is interesting because in Eastern Europe this cult is directly tied to post-communist capitalism. Dr. Topolanek sees his generation’s revolution as an internal one, one that allows people to change their bodies to whatever they want them to be. One of the best moments of this section shows Beba, who has been portrayed as an airhead up to this point, relaxing in a bath of warm chocolate (one of the therapeutic treatments) and musing upon the reproduction of Renior’s Woman with Parrot, hung on the wall. Beba’s thoughts carry us through an art history lecture that connects parrots with women’s sexuality in western art. This is a fun (and unexpected) tangent, but again illustrates why the book appealed to the Tiptree jury.

Here Ugresic criticizes the cult of youth and beauty. Her Croatian perspective is interesting because in Eastern Europe this cult is directly tied to post-communist capitalism. Dr. Topolanek sees his generation’s revolution as an internal one, one that allows people to change their bodies to whatever they want them to be. One of the best moments of this section shows Beba, who has been portrayed as an airhead up to this point, relaxing in a bath of warm chocolate (one of the therapeutic treatments) and musing upon the reproduction of Renior’s Woman with Parrot, hung on the wall. Beba’s thoughts carry us through an art history lecture that connects parrots with women’s sexuality in western art. This is a fun (and unexpected) tangent, but again illustrates why the book appealed to the Tiptree jury.

The third section continues on this scholarly tone. It begins with a letter that Dr. Aba Bagay, presumably the Bulgarian folklore student in section one, writes to an unknown editor who has asked her to read a manuscript and "explicate the correspondences between [the] author’s text and the myth of Baba Yaga" (239). The remainder of the section is her response, "Baba Yaga for Beginners," which discusses symbols related to Baba Yaga, supporting these with quotations from Eastern European myths and legends as well as quotations from scholars in the field, such as Maria Gimbutas and Marina Warner. Aba includes discussions of Baba Yaga’s name, her connection with witches and cannibalism and all her symbols, such as the hut, the mortar and pestle, birds and eggs. After each part, Aba provides "Remarks" that analyze the fictional author’s text in reference to the topic she just explained.

The surprising part is that the text that Aba is reading and commenting upon is made up of the two sections we just read. So, effectively, we have an author in the guise of an academic analyzing the book she just wrote. Ugresic shows her readers all of the Baba Yaga symbols and allusions that she included and they missed (at least many were missed on my part). For example, following her discussion of the hut, Aba writes:

Returning home, your author returns to the maternal ‘hut’ and repeats the initiation rite for the nth time. She must respect the law of Baba Yaga’s hut, otherwise Baba Yaga will eat her up. (263)

I’ve tried to find some other examples, but many of them give away too much about the plot. Just trust me; I couldn’t wait to finish each part so that Aba could connect my new knowledge of Baba Yaga to the previous plots. This set up makes for a very rich reading experience. I’ve never read a book before that taught its readers how to read it. I enjoyed being educated about the myth of Baba Yaga in this unorthodox manner.

I’ve tried to find some other examples, but many of them give away too much about the plot. Just trust me; I couldn’t wait to finish each part so that Aba could connect my new knowledge of Baba Yaga to the previous plots. This set up makes for a very rich reading experience. I’ve never read a book before that taught its readers how to read it. I enjoyed being educated about the myth of Baba Yaga in this unorthodox manner.

The ending brings in an element of the supernatural and that, along with the heavy dose of myths and folklore in section three and the magical realism of section two, shows me why this book was nominated for and won the Tiptree Award, even though at first glance this is not an obvious candidate. I found this book a very pleasurable read because I was continually intrigued about the way the story was being told.

Full Details

Full Details