RYO Review: The Gods Themselves by Isaac Asimov

Given his enormous output, I’m a very inexperienced Asimov reader but from what I understand his career in science fiction can be split into two major periods. The first covered the 1940s and 1950s, in which he wrote a great deal for the magazines that then dominated science fiction. Novels started appearing in 1950, starting with Pebble in the Sky, a novel of the Galactic Empire. So far I’ve read four of his books. The original Foundation trilogy and I, Robot. All of these have been published in the 1950-1953 period and lean heavily on work Asimov had produced in the 1940s. During the 1960s Asimov mostly wrote non-fiction. The Gods Themselves (1972) can be seen as something of a triumphant return to the genre. In this book he answers the critics of his earlier work, winning a Hugo, Nebula and Locus award in the process.

Given his enormous output, I’m a very inexperienced Asimov reader but from what I understand his career in science fiction can be split into two major periods. The first covered the 1940s and 1950s, in which he wrote a great deal for the magazines that then dominated science fiction. Novels started appearing in 1950, starting with Pebble in the Sky, a novel of the Galactic Empire. So far I’ve read four of his books. The original Foundation trilogy and I, Robot. All of these have been published in the 1950-1953 period and lean heavily on work Asimov had produced in the 1940s. During the 1960s Asimov mostly wrote non-fiction. The Gods Themselves (1972) can be seen as something of a triumphant return to the genre. In this book he answers the critics of his earlier work, winning a Hugo, Nebula and Locus award in the process.

The story is that of the discovery of the electron pump, a device that promised a clean and inexhaustible source of energy by using the different laws of nature that can be found in parallel universes. The story of its discovery one of coincidence and pettiness but the man being hailed as the inventor soon achieves rock star status. His influence on the scientific world is such that he leaves a trail of broken careers in his wake and suppresses information that threatens his status and the use of ‘his’ invention. Not everybody is discouraged by his bullying though. Doubts are being raised about the safety of the device. Soon a theory surfaces that suggests continued use might cause the sun to go nova. Bitterness, stupidity and infighting ensue.

When “Science Fiction” Is an Insult

Originally, I had intended to post the above video to further the ongoing conversation about what constitutes science fiction, as there can be few better authorities on the matter than a panel including Isaac Asimov, Harlan Ellison, and Gene Wolfe. But then, I discovered what had transpired shortly before this interview.

As it happens, Ellison’s view of science fiction was quite passionate. Carolyn Kellog, at the L. A. Times, reports that he had just come from assaulting his publisher for misclassifying “Spider Kiss” as a sci fi:

“I put him in a hold that I had learned from Bruce Lee. I took him to his knees. Then I duck-walked him back to his door,” on his knees all the way, Ellison recounts. The typing pool, all women then, stopped work and watched the show, he says, “with enormous pleasure.”

When they got back to the man’s office, the publisher on his knees, Ellison says he banged the man’s head into the door until he opened it. They went inside — the publisher, Ellison and Ellison’s editor, a woman he remembers fondly, who soon was huddling on a couch.

“I picked up a chair and threw it,” Ellison says. Rather than shattering the windows, “it bounced around the room.” The publisher had scrambled behind his desk and was dialing the phone.

“I jumped onto the desk and ripped the phone out of the wall,” Ellison says. Back in 1982, that’s how phones worked — they had cords, attached to walls. “He tried to crawl through the desk’s kneehole. I grabbed him by the collar and threw him across the room.”

From his comments in the interview, Mr. Ellison seems to share Margaret Atwood‘s view of the genre. Compare his comment to Mr. Turkel that sci fi is “women in brass braziers being molested by green-eyed monsters,” to Ms. Atwoods famous talking squids in outer space characterization.

We all know what was going on, back then. Certain authors didn’t want their books to be shoved in the back of the bookstore in the SF/F section. Writing is their bread and butter, and they wanted to get paid. Perhaps that is what made Harlan react with violence to the horrid insult of being called a science fiction writer.

Well, Harlan Ellison currently has 28 novels listed by WWEnd that we call “science fiction.” Perhaps I should get a bodyguard.

GMRC Review: The End of Eternity by Isaac Asimov

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

When I started reading science fiction, Heinlein, Asimov, and Clarke were the “big three” SF writers—already thought of as the authors of classics while they were still alive and writing. Of the three, Asimov was the favorite of my youth. I appreciated his rigorous logic, humanism, and devotion to the idea that human rationality and science would continue to move us forward into a challenging but ultimately triumphant future. Having not read his work for decades, I looked forward to reacquainting myself with Asimov, but with some trepidation, since it seems that the “Good Doctor” has lost some of his critical luster over the years, and it’s true that sometimes the favorites of adolescence are best left to remain as pleasant memories. David Pringle included The End of Eternity (1955) in his 100 Best, but only grudgingly: “He is one of the best-known sf writers in the world, so I felt I had to include something by Isaac Asimov, though I confess I have little enthusiasm for his work.” His essay on the novel certainly reflects that lack of enthusiasm.

Returning to the novel, the source of the difficulty with Asimov quickly became clear. Asimov, possibly more than any other author, embodies a common dichotomy in Golden Age science fiction: the focus is on ideas and plot, while characterization and prose style often do not hold up to the standards that modern genre readers expect. Asimov was open about the fact that his prose was purely functional and transparent—its job was to present the story without in itself being noticeable. For young readers, this may be especially appealing, but the success of the stories rides on the mind-blowing concepts and/or engaging plots on which Asimov’s fictions succeeds or fails. Readers looking for complex characterization or vivid descriptive writing will have to look elsewhere. But for anyone tolerant of such failings, or willing to overlook them in the interest of a good story, The End of Eternity still holds up as one of the great time travel novels, a nice blend of science fiction and mystery (a strength of Asimov’s), and a fine example of the author’s humanistic themes.

GMRC Review: The Gods Themselves by Isaac Asimov

Jeremy Frantz (jfrantz) reviews SF/F books on his blog The Hugo Endurance Project where he has given himself just 64 weeks to read every Hugo Award winner. This is his eighth GMRC review to feature in the blog and the second one this month.

Jeremy Frantz (jfrantz) reviews SF/F books on his blog The Hugo Endurance Project where he has given himself just 64 weeks to read every Hugo Award winner. This is his eighth GMRC review to feature in the blog and the second one this month.

Separated into three different but parallel stories, The Gods Themselves begins when scientists have discovered a way to exchange energy with another universe, the para-universe. Things get dicey when what is at first possibly the single greatest scientific achievement in history, threatens to become a horror story as it is understood that not only the two universes exchanging energy, but also physical laws which could result in our sun going nova.

Separated into three different but parallel stories, The Gods Themselves begins when scientists have discovered a way to exchange energy with another universe, the para-universe. Things get dicey when what is at first possibly the single greatest scientific achievement in history, threatens to become a horror story as it is understood that not only the two universes exchanging energy, but also physical laws which could result in our sun going nova.

Eternal contemporaneity

Published in ’72, winner in ’73, this is another title that it seems difficult to separate from the public scientific discourse of its time. The early 70’s marked the passage of some of the most monumental environmental protection regulations in American history. I saw The Gods Themselves very clearly drawing on the experience of environmental and consumer protection messages being hashed out on the national political stage. But before I’ve got you thinking this is a book about vast conspiracies and coordinated cover-ups, rest assured Asimov elevates his discussion to broader epistemological concerns and again draws on the sentiment of the times as he pulls in questions that, given the 1962 publishing of Thomas Kuhn’s, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, spoke to the very heart of the philosophy of science in his day.

GMRC Review: I, Robot by Isaac Asimov

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his fifth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his fifth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

For my fifth Grand Master reading challenge, this project may well be the only one at Random Comments that runs on schedule, I decided to read something by Isaac Asimov. Several of his novels feature prominently on all kinds of recommended reading lists and he is certainly one of the genre’s towering figures. I read his Foundation novels (the original trilogy) a while ago and I can’t say I was overly impressed. Asimov didn’t lack ideas but his prose is barely serviceable and he has the tendency to explain everything in great detail to his readers. Perhaps I should have picked something from later in his career but I, Robot (1950) is such an iconic work in the genre that I felt I should give it a go. Much to my surprise, I liked this book better than the Foundation novels. Not that the flaws in Asimov’s writing are absent in this novel, but the quality of the stories is more consistent and on the whole, I though them more entertaining as well.

I, Robot has been described as a fix-up novel or a short fiction collection. I think of it as the former but it is certainly true that most of the text appeared in the shape of various short stories between 1940 and 1950 in a Super Science Fiction Stories and of course John W. Campbell‘s Astounding Science Fiction, to whom the book is dedicated. Asimov has connected the stories with bits of interviews with Dr. Susan Calvin, a robotpsychologist working for U.S. Robots and Mechanical Men, Inc., as she is looking back on her long career in the field. She is not always the main character, or even a character, but she does provide just enough context to put the stories into a general future history. Asimov does this in his usual efficient way, not wasting a word more on it than absolutely necessary. I understand Asimov changed some of the details in the stories to make them more consistent. He is certainly making the most of repackaging these short stories with minimal effort here.

Being written in the 1940s, most or the novel is pretty badly dated and some of Asimov’s depictions of the future will seem decidedly strange to new readers. We have caught up with the start of the series now. I, Robot starts in 1996, with the story Robbie (1940), about a primitive robot and playmate of the eight year old Gloria. The girl treats the robot like she would a human friend and this makes her mother uneasy. Robbie wil have to go. Asimov uses the story to outline the resistance against artificial intelligence, the fear of superior robots replacing human beings. First in the work space and later completely. It is an introduction to his famous three laws of robotics, which he will name in the second story Runaround (1942).

"We have: One, a robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm."

"Right!"

"Two," continued Powell, "a robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law."

"Right!"

"And three, a robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws."

— Powell and Donovan discussing the Three Laws of Robotics – Runaround

Runaround, set in 2015, introduces the field testers Powell and Donovan and is a story in which Asimov examines the conflicts that may arise from these three laws. The laws are the kind of logic that Asimov seemed to have liked, simple, elegantly formulated and its intent easily understood. He was smart enough to see they are by no means flawless though. Most of the stories contain situations in which some conflict between these laws makes the robots behave unexpectedly or cause them to be caught in a loop, often jeopardizing the project they are working on or the lives of the unfortunate humans in their company. In Runaround it happens in the supremely hostile environment on Mercury, which shows just how little we knew about conditions on the planet in 1940. It gives Asimov plenty of room to speculate though.

Some six months after events in Runaround Donovan encounter a different sort of problem. In Reason (1941), which I consider to be one of the strongest stories, Asimov takes a more philosophical tone when our field testers are stuck with a robot who will not accept the (in its opinion) contrived and unnecessarily complicated explanation for its existence. A case of Occam’s razor gone blunt I suppose. This story contains the most memorable quote in the book if you appreciate sarcasm.

"I have spent these last two days in concentrated introspection", said Cutie, "and the results have been most interesting. I began at the one sure assumption I felt permitted to make. I, myself exist, because I think…"

Powell groaned, "Oh Jupiter, a robot Decartes!"

— QT-1 discussing its own existence.

Cutie retreats from reality along the same lines as a human being might do in the end by resorting to religion, shutting out the need for an explanation. It is one of several instances where robotpsychology runs parallel to human psychology. Something even Susan Calvin reluctantly admits later on in the book.

In Catch That Rabit (1944) robot behaviour shows some parallels to buggy software as well. It sees our field testers use drastic measures to get the robot back under control. Asimov spends a lot of the later part of the story lecturing (disguised as a conversation between Powell and Donovan). I can’t say I particularly liked it. Liar! (1941) is more interesting. Set in 2121, it deals with a robot that can read minds. The conflict arises when it receives one set of instructions verbally, that don’t correspond with the real desires of the person giving the instructions. Calvin’s behaviour in this story will no doubt make some readers groan but the concept is a strong one.

By the time of Little Lost Robot (1947), robots have become quite advanced and exploration of the solar system is well under way. In 2029, one such space program employs robots with a slightly altered set of robotic laws, enabling them to ignore a human being putting themselves in danger. If the mere existence of such a robot was to become public knowledge on earth, the political consequences would be dire. When one of the robots is lost, the people who run the project are in deep trouble. Calvin is called upon to find it. The three laws of robotics can be quite a restriction I suppose, so the temptation to do away with them is clear. Asimov presents a perfectly reasonable argument for doing so in this story. It might have worked better if there had been more of an element of danger in the story though. The missing robot is still unable to actively do harm. Personally I wouldn’t have been particularly worried to have it around.

By the time of Little Lost Robot (1947), robots have become quite advanced and exploration of the solar system is well under way. In 2029, one such space program employs robots with a slightly altered set of robotic laws, enabling them to ignore a human being putting themselves in danger. If the mere existence of such a robot was to become public knowledge on earth, the political consequences would be dire. When one of the robots is lost, the people who run the project are in deep trouble. Calvin is called upon to find it. The three laws of robotics can be quite a restriction I suppose, so the temptation to do away with them is clear. Asimov presents a perfectly reasonable argument for doing so in this story. It might have worked better if there had been more of an element of danger in the story though. The missing robot is still unable to actively do harm. Personally I wouldn’t have been particularly worried to have it around.

In Escape! (1945), positronic brains have become so advanced they are capable of calculations comparable of those of a super computer. The Brain, as this robot is called, is set to the task of creating the means for interstellar travel, a problem that has already cracked a competing robot. Calvin is aware that there is a conflict with the three laws but doesn’t know where. The company tries to avoid the problem by feeding The Brain the information is small sections. It features a lot of irrational behaviour on the Brain’s part. I’m not particularly fond of this story but as usual, Asimov’s rationale is perfectly logical.

The book then moves on to 2032, a year that poses a completely different challenge to Susan. A Turing with a twist. In Evidence (1946), Stephen Byerley is a brilliant district attorney running for mayor, when one of his opponents accuses him of being a robot. How do you prove someone is a robot when the subject is not cooperating and very aware of his rights? Written during the aftermath of the second world war, it is easy to see what Asimov (of Russian Jewish descent himself) was aiming at. It is the most politically charged story in the book, with a lot of it focussing on the suspicion and outright hatred of robots despite the fact they are incapable of harming a human being. Where Asimov usually explains the entire plot to the reader in detail, this story is certainly food for thought.

Interestingly enough I, Robot then goes to show us some suspicion of robots might actually be warranted. In The Evitable Conflict (1950), set in 2052, Calvin has realized that robots rule the world. They are responsible for the allocation of goods and services and the division of labour of the entire planet, which by that time is divided into four super states. Calvin is called upon to explain apparent imperfections in the solution the robots provide. These turn out to have a perfectly reasonable explanation in line with the three laws of course. This story has aged very badly, Asimov’s future, at this point in time, seems positively silly, although from his perspective it might not have been entirely impossible. It was not my favourite part of the book though. Partly because of Asimov’s tendency to explain everything and partly because of the fact that the plot is mostly a guided tour though planetary government in 2052.

With I, Robot Asimov lays the foundation of what would become one of the three main series in his career as a science fiction writer. He is not technically a good writer (at this point in his career at least) but back in the days where science fiction was very much seen as the literature of ideas, you probably couldn’t do much better than Asimov. He had ideas and was not afraid to explain them at length. For the modern reader a lot of I, Robot is dated but with lasting contributions to the genre such as the three laws of robotics and the positronic brain, it is one of the novels that shaped the genre. One of the thoughts that kept returning while reading this novel is just how many things Asimov discussed that were in the experimental stage at the time, or didn’t exist at all. All things considered, I think it deserves at least some of the praise that is heaped on it.

GMRC Review: The Stars, Like Dust by Isaac Asimov

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog. This is Allie’s second GMRC review.

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog. This is Allie’s second GMRC review.

The Stars, Like Dust by Isaac Asimov

The Stars, Like Dust by Isaac Asimov

Published: Doubleday, 1951

Series: The Galactic Empire Book 2

The Book:

“Biron Farrell was young and naïve, but he was growing up fast. A radiation bomb planted in his dorm room changed him from an innocent student at the University of Earth to a marked man, fleeing desperately from an unknown assassin.

He soon discovers that, many light-years away, his father, the highly respected Rancher of Widemos, has been murdered. Stunned, grief-stricken, and outraged, Biron is determined to uncover the reasons behind his father’s death, and becomes entangled in an intricate saga of rebellion, political intrigue, and espionage.

The mystery takes him deep into space where he finds himself in a relentless struggle with the power-mad despots of Tyrann. Now it is not just a case of life or death for Biron, but a question of freedom for the galaxy.” ~barnesandnoble,com

I’ve been a big fan of Asimov’s work, ever since I discovered I, Robot as a kid. I’ve since read the majority of his novels and short stories, but I’d never read any of this particular trilogy (Pebble in the Sky, The Stars, Like Dust, and The Currents of Space). Thus, when I saw The Stars, Like Dust in a used bookstore, I grabbed it. If I’d done a little research first, I suppose that I would have discovered Asimov has apparently referred to this one as his “least favorite novel.” In any case, it’s an interesting look at a lesser, early novel of Asimov’s. The Stars, Like Dust, contains a standalone story, so I don’t think the novels that comprise this trilogy need to be read in order.

Sadly, there won’t be much more Asimov featured on my blog, only because I’ve pretty much read most of his work, and I don’t generally re-read. If you really want to get into Asimov (and who wouldn’t?), his robot short stories are a good place to start.

My Thoughts:

The Stars, Like Dust seems like a pretty typical pulp SF adventure story. There’s an evil empire (the Tyranni), a plucky young hero with a crew cut and well-trained muscles (Biron), a secret rebellion, a feisty love interest (a pretty girl named Artemisia), and even a helpful old inventor. Most of the details of the plot, and the various twists, seem pretty clichéd, though I imagine that might not have been the case back when it was published.

The Stars, Like Dust seems like a pretty typical pulp SF adventure story. There’s an evil empire (the Tyranni), a plucky young hero with a crew cut and well-trained muscles (Biron), a secret rebellion, a feisty love interest (a pretty girl named Artemisia), and even a helpful old inventor. Most of the details of the plot, and the various twists, seem pretty clichéd, though I imagine that might not have been the case back when it was published.

The characters do little to break out of their one dimensionality. Artemisia has little to do in the story besides fall for the hero; she’s an aristocrat on the run from her arranged marriage with a powerful older man. Biron is the typical naïve, ignorant young man who ends up being somehow vastly more capable—physically and mentally—than everyone around him. It doesn’t help that the writing itself also seems clunky, and the dialogue doesn’t seem to flow naturally. There is also a rather ridiculous subplot about mysterious ‘important Earth document’, which I have heard was added against Asimov’s will.

If you’re willing to go along with a fair amount of cheesiness, however, the story is pretty fun. I think that The Stars, Like Dust is clearly one of many similar stories that contributed to the imagining of Star Wars, though this earlier novel misses some of the strengths in plot and character that made Star Wars such a cultural phenomenon. The Stars, Like Dust, is a fast read, and I kind of enjoyed reading such an example of campy 50’s Sci-Fi.

My Rating: ~/5

The truth is, I don’t want to rate this novel. Therefore, I won’t. I can’t in good conscience say it is a good novel. However, I did enjoy it, at least as a glimpse into Asimov’s earlier, lesser-known work. This is also, apparently, Asimov’s least favorite novel, so it was interesting to see what he considers the worst of his large and mostly impressive body of work. I think The Stars, Like Dust is a novel that would mostly appeal to Asimov completionists, though it’s also a fun, short little novel for anyone who wants a dose of good-natured, corny, 50s-style, pulp SF star-spanning adventure.

YA Genre Fiction Month: Foundation

“There were nearly twenty-five million inhabited planets in the Galaxy then, and not one but owed allegiance to the Empire whose seat was on Trantor. It was the last half-century in which that could be said.”

Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series is magnificently ambitious, inspired as it was by Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, but painted on a galactic canvas. After twelve thousand years in the stars, the human Galactic Empire is on the decline, and the psychohistorian Hari Seldon may be the only person who can prevent tens of thousands of years of barbarism and social decay. What’s psychohistory, you ask? It’s a science that Asimov invented solely for use in this series, one that merges psychology, history and mathematics to predict human behavior on a large scale over long periods of time.

Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series is magnificently ambitious, inspired as it was by Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, but painted on a galactic canvas. After twelve thousand years in the stars, the human Galactic Empire is on the decline, and the psychohistorian Hari Seldon may be the only person who can prevent tens of thousands of years of barbarism and social decay. What’s psychohistory, you ask? It’s a science that Asimov invented solely for use in this series, one that merges psychology, history and mathematics to predict human behavior on a large scale over long periods of time.

Seldon paints a bleak picture of the coming imperial collapse: “The Empire will vanish and all its good with it. Its accumulated knowledge will decay and the order it has imposed will vanish. Interstellar wars will be endless; interstellar trade will decay; population will decline; worlds will lose touch with the main body of the Galaxy. And so matters will remain…. The dark ages to come will endure not twelve, but thirty thousand years.” This collapse, Seldon says, cannot be prevented, but its effects can be minimized and its length shortened to a mere one thousand years.

His solution is to set up two Foundations, colonies where the collected knowledge and science of mankind is preserved and protected, one on each end of the galaxy. The Foundation established on the planet Terminus is the one followed by the narrative, and it has no contact with the other. Every few decades a “Seldon Crisis”—an event of massive social upheaval—occurs in a way predicted by Seldon, and Terminus acts how Seldon needed them to act in order to maintain his plan.

His solution is to set up two Foundations, colonies where the collected knowledge and science of mankind is preserved and protected, one on each end of the galaxy. The Foundation established on the planet Terminus is the one followed by the narrative, and it has no contact with the other. Every few decades a “Seldon Crisis”—an event of massive social upheaval—occurs in a way predicted by Seldon, and Terminus acts how Seldon needed them to act in order to maintain his plan.

One of the most difficult subjects for me as a young adult was history, particularly because it was so hard to find meaningful patterns in the larger scope of world events. It’s not hard to poke holes in Gibbon’s theories of history, but he certainly provided a rousing narrative that made sense of many historical data. Asimov likewise provides a narrative spanning centuries (actually, twenty thousand years if you include the entire expanded series), and while his ideas of how historical movements occur are perhaps a bit on the naïve side, they are full of enough imagination to make even the most skeptical student believe that history might not be so boring after all.

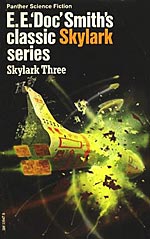

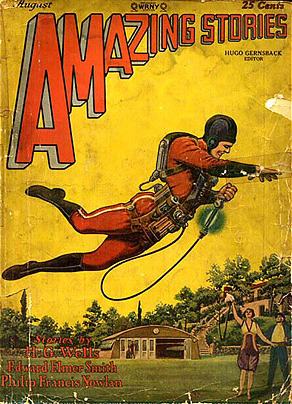

In Praise of Pulp

I have a confession to make. I. Love. Pulp. Pulp science fiction, that is.

I have a confession to make. I. Love. Pulp. Pulp science fiction, that is.

Ever since I was a kid I’ve been enamored of Pulp SF. I love the cheesy, and often-times racy, over-the-top Buck Rogers covers: the muscular man of action chasing down the fiendish alien abductor who’s trying to make off with the dame. And what a dame! Scantily-clad buxom lasses all – with incongruous fish bowl helmets that somehow hold back the vacuum of space but never muss their flowing locks. And rockets! Always with the rockets! Rocket shaped space ships poised for takeoff from some exotic alien planet with multiple moons and a few rings thrown in for good measure. That’s how you know its sci-fi, my friends.

But the goodness is not just on the front cover. Turn a pulp over and you get the glory of the blurb. The blurb never fails to amuse and entice with a combination of ridiculous hyperbole and hopelessly anachronistic phrasing. You know you’re reading a pulp blurb when you find yourself doing the Batman TV show voiceover as you read the synopsis. Go ahead; try reading the blurb for The Skylark of Space by E.E. “Doc” Smith below. You almost have to go all Batman on it.

“Scientist Richard Seaton had discovered the secret of the complete release of ultimate energy. And his discovery gave him the key to the exploration of the Universe in all its cosmic immensity. But Seaton’s arch-rival, the powerful, unscrupulous Duquesne, was determined to gain control of this awesome secret too…

The climax came in deep space, when Seaton, Duquesne and three others – two of them women – were marooned, countless light-years from Earth, with only one chance in a million of ever returning…”

Ultimate energy AND cosmic immensity? Two of them women for crying out loud! What’s not to love?

But wait, there’s more!

Pulp books are a feast for the senses! Of course, I’m talkin’ ‘bout proper books here. You know. With pages. Not sterile digital versions on your iSomething™ or Kindle. Great as those devises are, and I love them too so don’t start hating; they just don’t do a pulp justice. I love the dry texture of the brittle binding and chipped corners and the scritch-scratch sound of stiff yellowed pages turning. There is no yellow like the yellow of old pulp pages. You won’t find that in your Crayola box. Then there’s the pleasantly musty smell of old paper and ink. The noble rot. You can smell it now, can’t you? Ah yes. So much for eInk. And the dust. What’s a pulp without years of accumulated bookstore dust? Your Nook won’t make you sneeze like that.

But, of course, all of that is secondary to the real joy of a pulp: the story. Oh, the stories you’ll read.

The best pulps are short and fast reads with minimal exposition and break-neck pacing. Get in and get out. Hang on as best you can. They are rollicking adventures with no pretense to anything other than a good time. You see, there is very little depth to a pulp. No political undercurrent or social commentary. No complex structure or moral ambiguity. It’s all on the shiny space-age polymer surface. They are gloriously and unabashedly formulaic from beginning to end.

In a good pulp you’ll find enough SF tropes to make Margaret Atwood roll her eyes. These stories established the stereotypes after all. The pulp future has it all. Flying cars, ray guns, robots and time machines. Space stations, silver jump suits and artificial gravity. Galactic empires, floating cities and epic battles. Exotic aliens, beautiful women and strapping heroes. And even “talking squids in outer space.”

What about the characters? They are exactly as awesome as they are predictable and cliché.

The good guys are good guys ‘cause how else would they be? They epitomize honor and chivalry and self reliance. You want to be the good guy because he’s a badass. He gets the girl on the cover and always metes out justice to the villains along the way. True men of action like John Carter of Mars:

“I am a citizen of two worlds; Captain John Carter of Virginia, Prince of the House of Tardos Mors, Jeddak of Helium. Take this man to your goddess, as I have said, and tell her, too, that as I have done to Xodar and Thurid, so also can I do to the mightiest of her Dators. With naked hands, with long-sword or with short-sword, I challenge the flower of her fighting-men to combat.”

You don’t pull the mask off the old Lone Ranger and you don’t mess around with John….

The good women embody old time virtues of the fairer sex: beauty, grace and love with a healthy dose of can-do attitude while always remaining more or less helpless and pliant as the plot dictates. You’ll have to forgive them that. It was a different time and besides, a hero needs someone to save.

The bad guys are bad because they can’t compete with the good guys any other way. Many of the best bad guys are aliens. They’ve been poking around in our collective anus for decades – of course they’re the baddies!

“Hideous egotist,” said O-Tar, “prepare to die and assume not to dictate to O-Tar the jeddak. He has passed sentence and all three of you shall feel the jeddak’s naked steel. I have spoken!”

You just know the bad guy is gonna die after a pronouncement like that.

The bad gals are spurned lovers or victims turned cruel. They’re angry and opportunistic and sexy as all get out. They have to tempt the good guys you know. No gray areas in these characters. You’re never supposed to empathize with the bad seeds. That would just slow things down. Your job is to recognize that they’re bad and revel in their comeuppance when it eventually arrives.

Both heroes and villains alike avail themselves of the most outlandish “science” and technology imaginable. This is where the gloves come off. Pulp revels in elaborate scientific explanations that are both silly and wonderful in the extreme. There are pages of this stuff in the Skylark Series:

“The zone of force is necessary to shield certain items of equipment from ether vibrations; as any such vibration inside the controlling fields of force renders observation or control of the higher orders of rays impossible.”

Um, yeah. May the fields of force be with you.

Of course, sometimes the author can’t be bothered with too much jargon and opts to explain it all away as the product of advanced alien intelligence beyond our ken. I’ll buy that. Action is the name of the game in pulp and the second option leaves more room for space battles so we still come out winners in the end. There is no time to waste on physics or relativity. This is all pre-wormhole or subspace stuff here so it’s all about speed! The Kessel Run in four parsecs? A walk in the park. These guys fly to the other side of the galaxy at “titanic speeds”, save the day and make it back in time for a cold one.

Yes, yes, you’re right. There are certainly better books to be reading. Books that read like a steak dinner with a nice Chianti followed by an indie film. They leave you wondering about life the universe and everything. Maybe even touch your life or say something to you. I love those books too.

But every so often, I like to travel “back to the future” – to the beginnings of the genre for a ripping yarn told with earnest joy. Pulp SF books are popcorn and candy, domestic beer and an old B-movie with friends. They leave you breathless and bemused and wanting more. They make you smile and feel nostalgic. They take you away from things serious and mundane for a little while and they don’t demand too much. What more could you ask?

If you’ve never read pulp SF, give it a try. You don’t know what you’re missing. I have spoken.

Some great pulp series to consider:

- Barsoom Series by Edgar Rice Burroughs

- Before the Golden Age edited by Isaac Asimov

- Lucky Starr Series by Isaac Asimov

- Skylark Series by E.E. “Doc” Smith

- Lensman Series by E.E. “Doc” Smith

- The Conan Chronicles, Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle by Robert E. Howard

- The Conan Chronicles, Volume 2: The Hour of the Dragon by Robert E. Howard

Asimov Hits the Big Screen?

In the early days of the Hugo Awards, there must have been nominees… but nobody seems to know what they were. So, for all we know, The End of Eternity might be a 1955 Hugo nominee. After all, the author was the great Isaac Asimov who got the nom on half a dozen other occasions, and usually won.

At least we hope The End of Eternity is a Hugo nominated book, because that would give us an excuse to talk about this: Empire Online is reporting that the Asimov classic was just greenlighted to become a feature film. Read all about it.

Full Details

Full Details