GMRC Review: The Legion of Space by Jack Williamson

Chris Uhl (chuhl) can’t remember a time when he wasn’t a science fiction fan. He has a B.A. in Classics from Vassar College and an M.A. in English Literature from the University of Virginia. He has worked as a teacher, a legal assistant, a college development officer, a salesman, and a film extra. Chris may be the only WWEnd reviewer who has no blog. This is his first GMRC review to feature in the WWEnd blog.

Chris Uhl (chuhl) can’t remember a time when he wasn’t a science fiction fan. He has a B.A. in Classics from Vassar College and an M.A. in English Literature from the University of Virginia. He has worked as a teacher, a legal assistant, a college development officer, a salesman, and a film extra. Chris may be the only WWEnd reviewer who has no blog. This is his first GMRC review to feature in the WWEnd blog.

I’m a big fan of space opera, but I’ve never read E. E. “Doc” Smith or Jack Williamson because I’ve always heard that, although their importance in the genre’s history is undeniable, their prose style is an ordeal for modern readers. So I took advantage of the GMRC to try Williamson’s The Legion of Space.

I’m a big fan of space opera, but I’ve never read E. E. “Doc” Smith or Jack Williamson because I’ve always heard that, although their importance in the genre’s history is undeniable, their prose style is an ordeal for modern readers. So I took advantage of the GMRC to try Williamson’s The Legion of Space.

Yes, the prose does tend towards the purple end of the spectrum. It’s formal and intense and rather melodramatic by our standards. But if you‘re willing to give it a chance, you find yourself in the hands of an author who’s clearly having fun trying to dazzle and horrify you with the wonders and terrors that our heroes face in their quest to save the solar system from destruction. It’s like when someone tells you a ghost story around a fire. You can roll your eyes and hang on tight to your disbelief and sneer, or you can get into the spirit of the occasion and have fun with it. If you meet him halfway, Williamson’s writing can be very vivid and suspenseful and powerful.

For example, here’s an excerpt in which our four heroes, having crash-landed on a hostile planet, find themselves adrift on a log that isn’t as safe as it first appeared. At the other end of the log they see a slimy creature that looks like “a gigantic amoeba”:

Forays into Fantasy: Darker Than You Think by Jack Williamson

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Note: This blog post also counts as a Grand Master Reading Challenge review.

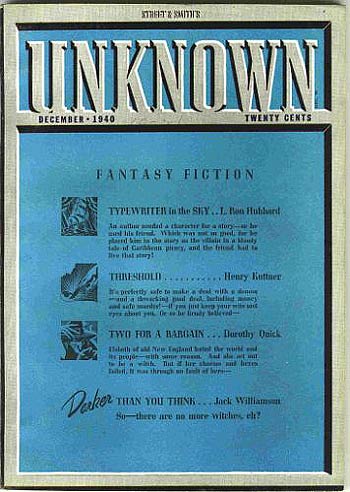

Between March 1939 and October 1943, John W. Campbell edited a magazine called Unknown (later Unknown Worlds)—a fantasy companion to Astounding, which at that time was at the peak of its influence in the science fiction world. Campbell wanted to create a contrast to the uncanny horror of Weird Tales, and sought out fantasy stories with logical underpinnings for the fantastic elements, a high intellectual/literary level, and often humor. I previously reviewed A. E. Van Vogt’s The Book of Ptath, which originally appeared in the final issue of Unknown. Its extreme far-future setting left open the possibility that what we would normally take to be fantasy elements had a science fictional explanation. Other writers with backgrounds in science fiction also contributed to Unknown, including L. Ron Hubbard, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, and Henry Kuttner. L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Harold Shea sequence (collected as The Complete Enchanter) and Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series got their starts here as well. Jack Williamson’s “Darker Than You Think” first appeared as a novella in the December 1940 issue.

Between March 1939 and October 1943, John W. Campbell edited a magazine called Unknown (later Unknown Worlds)—a fantasy companion to Astounding, which at that time was at the peak of its influence in the science fiction world. Campbell wanted to create a contrast to the uncanny horror of Weird Tales, and sought out fantasy stories with logical underpinnings for the fantastic elements, a high intellectual/literary level, and often humor. I previously reviewed A. E. Van Vogt’s The Book of Ptath, which originally appeared in the final issue of Unknown. Its extreme far-future setting left open the possibility that what we would normally take to be fantasy elements had a science fictional explanation. Other writers with backgrounds in science fiction also contributed to Unknown, including L. Ron Hubbard, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, and Henry Kuttner. L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Harold Shea sequence (collected as The Complete Enchanter) and Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series got their starts here as well. Jack Williamson’s “Darker Than You Think” first appeared as a novella in the December 1940 issue.

Williamson’s career spans the history of science fiction. Born in 1908, his family traveled by covered wagon from Arizona to their New Mexico homestead, where Williamson discovered the early science fiction pulps and became entranced by imaginary worlds incredibly distant from his family’s rural ranching existence. He published his first story in a 1928 issue of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories, and released his final novel in 2005, just prior to his death at age 98. Already well known for early space operas such as The Legion of Space and The Legion of Time, he made the transition to the more mature Astounding style in the ‘40s with stories like The Humanoids, and later published multiple collaborations with Frederik Pohl. Along the way, he managed to begin college in the 1950s, eventually getting his Ph.D. and teaching for many years at Eastern New Mexico University. Along with his amazing science fiction resume, he managed to publish some influential fantasy during his career, and Darker Than You Think is usually considered to be one of his best novels.

Darker Than You Think, expanded to novel length in 1948, is a good example of Unknown-style fantasy, and fits into a long tradition of updating ancient fantastic traditions (in this case, werewolves and witchcraft) in order to maintain their relevance and interest for modern audiences. (Rereading Bram Stoker’s Dracula recently, I was surprised at the emphasis on science in the understanding and combating of the vampire, which must have helped update the old legends for a late nineteenth-century readership.) As in The Book of Ptath, there is a science fictional explanation for Williamson’s story of a race of magical beings threatening humanity. Usually remembered as a story about werewolves, the supernatural creatures of Darker Than You Think also encompass witches, vampires, were-beasts of all forms, and psychics. The basic conceit is that all these supernatural manifestations, as well as all the stories of monsters and gods throughout all human mythologies (including the snake in the Garden of Eden!), can be traced back to the existence of Homo lycanthropus, an offshoot of the genus Homo which competed for dominance with other pre-human species. Think of it as an evolutionary alternate history.

Darker Than You Think, expanded to novel length in 1948, is a good example of Unknown-style fantasy, and fits into a long tradition of updating ancient fantastic traditions (in this case, werewolves and witchcraft) in order to maintain their relevance and interest for modern audiences. (Rereading Bram Stoker’s Dracula recently, I was surprised at the emphasis on science in the understanding and combating of the vampire, which must have helped update the old legends for a late nineteenth-century readership.) As in The Book of Ptath, there is a science fictional explanation for Williamson’s story of a race of magical beings threatening humanity. Usually remembered as a story about werewolves, the supernatural creatures of Darker Than You Think also encompass witches, vampires, were-beasts of all forms, and psychics. The basic conceit is that all these supernatural manifestations, as well as all the stories of monsters and gods throughout all human mythologies (including the snake in the Garden of Eden!), can be traced back to the existence of Homo lycanthropus, an offshoot of the genus Homo which competed for dominance with other pre-human species. Think of it as an evolutionary alternate history.

They “sprang from another kindred type of Hominidae who were trapped by the glaciers [during the Ice Age] in the higher country … toward Tibet… They had to adapt, or die. They responded, over the slow millennia, by evolving new powers of the mind… [They] learned to leave their bodies hibernating in their caves while they went out across the ice fields—as wolves or bears or tigers—to hunt human game… In a few thousand years, their dreadful powers had overcome every other species of the genus Homo.”

Being predators, the lycanthropes allowed a larger pre-human population to live on for use as slaves and food. “They had learned to like the taste of human blood, and they couldn’t exist without it.” But around a hundred thousand years ago Homo sapiens arose, and began fighting back, discovering that silver weapons and domesticated dogs could help them in the war against Homo lycanthropus, eventually prevailing in that “strange war.” But before being wiped out entirely, these predatory creatures managed to interbreed with Homo sapiens, so that most modern humans have some trace of that genetic heritage, thus providing a scientific explanation, based on evolution and genetics, for all sorts of superhuman manifestations and witch hunts, not to mention individual psychological conflicts—“that alien inheritance haunts our unconscious minds with the dark conflicts and intolerable urges that Freud discovered and tried to explain.” Mental illness is thus presented as a result of this pre-human war still being waged in our genes! (For more on how this aspect of the novel might be related to Williamson’s own experience with psychotherapy, see Charles Dee Mitchell’s excellent WWEnd review of the novel.)

And how do these genetically-determined powers work? Well… it turns out that the mind is “an energy complex… created by the vibrating atoms and electrons of the body, and yet controlling their vibrations through the linkage of atomic probability…” Homo lycanthropus developed the power to enter a “free state,” in which this energy complex, which might be the “soul,” can disengage from the physical body. “We simply separate that living web from the body, and use the probability link to attach it to other atoms, wherever we please—the atoms of the air are easiest to control… Light can destroy or damage that mental web,” so the free state can only be entered at night. “No common matter is any real barrier to us in the free state… Our mind webs can grasp the vibrating atoms and slip through them, nearly as easily as through the air… Silver is the deadly exception—as our enemies know.” This pseudoscientific exposition is part of protagonist Will Barbee’s initiation into the ways of these witches and shape shifters. As dialogue, it’s not at all convincing, but the explanations presented in such “info dumps” are surprisingly consistent logically.

And how do these genetically-determined powers work? Well… it turns out that the mind is “an energy complex… created by the vibrating atoms and electrons of the body, and yet controlling their vibrations through the linkage of atomic probability…” Homo lycanthropus developed the power to enter a “free state,” in which this energy complex, which might be the “soul,” can disengage from the physical body. “We simply separate that living web from the body, and use the probability link to attach it to other atoms, wherever we please—the atoms of the air are easiest to control… Light can destroy or damage that mental web,” so the free state can only be entered at night. “No common matter is any real barrier to us in the free state… Our mind webs can grasp the vibrating atoms and slip through them, nearly as easily as through the air… Silver is the deadly exception—as our enemies know.” This pseudoscientific exposition is part of protagonist Will Barbee’s initiation into the ways of these witches and shape shifters. As dialogue, it’s not at all convincing, but the explanations presented in such “info dumps” are surprisingly consistent logically.

The alcoholic Barbee has never felt settled in his life, and it quickly becomes clear that his psychological issues are related to his own genetic heritage. His infatuation with the beautiful April Bell sets him on a path that will force him to choose between humanity and the exhilaration of the “free state” he has begun to experience in what he assumes to be his dreams. Like Dracula’s Von Helsing, a team of scientists has discovered the truth about the lycanthropes. These men were once Barbee’s colleagues, and he still considers them his friends, thus ratcheting up his mental conflict as it comes to be mirrored by the actual conflict between the scientists and the ancient race. The lycanthropes are determined to stop these men by any means necessary, while continuing the long game of regaining their ascendancy over humanity—a game that is nearing fruition, as they await the appearance of the their born leader, the “child of night.” By the end of the story, we know the culmination of their plans.

Interesting and entertaining as it is, Darker Than You Think does not entirely hold up. Its length could be trimmed. (I don’t have access to the original novella, but Cawthorn and Moorcock, in their guide to the best fantasy books, argue that the shorter version is superior, and they list it chronologically as belonging to 1940 rather than 1948.) As a writer, Williamson had matured from his pulp beginnings, but some “pulpishness” remains, as evidenced by the sort of dialogue quoted above, and a tendency toward the repetitive use of certain descriptive terms (e.g., Barbee seems to “shudder” an awful lot). Barbee’s character is also problematic. Using a confused and divided (literally!) point of view character is an intriguing idea, but Barbee’s continual vacillation and inability to understand what is happening to him despite overwhelming evidence, while potentially plausible given his mental state, is nonetheless annoying in a protagonist. But if you can accept the writing deficiencies (which anyone for a fondness for the pulps will easily be able to do), the rewards come when Williamson describes the freedom and power of the transformation:

Interesting and entertaining as it is, Darker Than You Think does not entirely hold up. Its length could be trimmed. (I don’t have access to the original novella, but Cawthorn and Moorcock, in their guide to the best fantasy books, argue that the shorter version is superior, and they list it chronologically as belonging to 1940 rather than 1948.) As a writer, Williamson had matured from his pulp beginnings, but some “pulpishness” remains, as evidenced by the sort of dialogue quoted above, and a tendency toward the repetitive use of certain descriptive terms (e.g., Barbee seems to “shudder” an awful lot). Barbee’s character is also problematic. Using a confused and divided (literally!) point of view character is an intriguing idea, but Barbee’s continual vacillation and inability to understand what is happening to him despite overwhelming evidence, while potentially plausible given his mental state, is nonetheless annoying in a protagonist. But if you can accept the writing deficiencies (which anyone for a fondness for the pulps will easily be able to do), the rewards come when Williamson describes the freedom and power of the transformation:

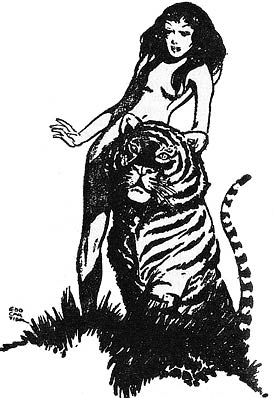

“Even by the colorless light of the stars, Barbee could see everything distinctly—every rock and bush beside the road, every shining wire strung on the striding telephone poles. ‘Faster, Will!’ April’s smooth legs clung to his racing body. She leaned forward, her breasts against his striped coat, her loose red hair flying in the wind, calling eagerly into his flattened ear… He stretched out his stride, rejoicing in his boundless power. He exulted in the clean chill of the air, the fresh odors of earth and life that passed his nostrils, and the warm burden of the girl. This was life. April Bell had awakened him out of a cold, walking death. Remembering that frail and ugly husk he had left sleeping in his room, he shuddered as he ran. ‘Faster!’ urged the girl. The dark plain and the first foothills beyond flowed back around them like a drifting cloud.”

Werewolf legends have been traced back as far as the eleventh century. Their enduring appeal has been attributed to the transgressive desire to escape the constraints of civilization and unleash primitive animalistic desires. Jack Williamson’s story of ancient racial conflict raises another possibility: Given the choice, who wouldn’t prefer to be predator rather than prey?

Next: Gothic novels of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

GMRC Review: Darker Than You Think by Jack Williamson

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s second GMRC review.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s second GMRC review.

Newspapermen and one gorgeous, redheaded, green-eyed newspaperwoman wait on the chilly tarmac of the Clarendon airport for the chartered plane returning the Lamarck Mondrick expedition from their two your stint in Nala-Shan. (Nala-shan actually exists. It’s a mountain range in Northern China between Ninxgia and inner Mongolia’s Alxa League. This could be the only trace of verifiable fact Williamson brings to his novel.) Along with the press are family members of the four returning explorers, including the elderly, stately Rowena Mondrick, blind since a panther ripped out her eyes in Nigeria some years before.

Newspapermen and one gorgeous, redheaded, green-eyed newspaperwoman wait on the chilly tarmac of the Clarendon airport for the chartered plane returning the Lamarck Mondrick expedition from their two your stint in Nala-Shan. (Nala-shan actually exists. It’s a mountain range in Northern China between Ninxgia and inner Mongolia’s Alxa League. This could be the only trace of verifiable fact Williamson brings to his novel.) Along with the press are family members of the four returning explorers, including the elderly, stately Rowena Mondrick, blind since a panther ripped out her eyes in Nigeria some years before.

Mark Barbee is there, an old friend of the explorers and now an alcoholic reporter for the Star. He introduces himself to the beautiful readhead, April Bell, novice reporter for Clarendon’s rival newspaper. She carries a small snakeskin bag that holds an adorable black kitten. Don’t get too attached to the kitten.

The plane lands, the much aged and visibly frightened explorers descend the ramp. They carry a heavily locked green case. The enfeebled Mondrick begins a speech, promises world-shattering revelations, then dies of asthma or a heart attack or a combination of the two, Much consternation. April Bell vanishes, but Matt Barbee has already made a date for later that night. His nose for news leads him to a dumpster near the airport terminal where he finds the snakeskin bag containing the kitten. It’s been strangled by a red ribbon and it’s heart punctured by an ivory pin decorated with a running wolf. It must be that same nose for news that does not make Barbee consider canceling his date.

This is the set-up for Jack Williamson‘s Darker Than You Think. (Oh, in case you need more clues to coming events, Rowena Mondrick drapes herself in silver jewelry and her mastiff, wearing a silver-studded collar, goes beserk when he sees April Bell.)

Williamson’s novel first appeared in John W. Cambell’s Astounding in 1940 as a 40,000 word serial. After WWII, the market for science fiction changed. Pulps were losing out to radio and paperbacks, but the now grown-up kids who loved sf from its pulpy origins wanted to see the stories in book form. Lloyd Arthur Eschbach founded Fantasy Press in 1946 and brought out Williamson’s The Legion of Space. Respectable sales prompted Llyod to ask Williams to double the length of Darker Than You Think, and its sales equaled those of the previous novel. It’s been reprinted many times. The edition I read was a Dell 1979 paperback that reproduced the original drawings by Edd Cartier, whose work, according the book’s blurb, adds an extra dimension of enjoyment. Well, maybe. Certainly it adds an extra dimension of camp. My favorite is the frontispiece that features a nude woman seated on the back of a sabre-tooth tiger. She has the perky but nipple-free breasts not uncommon to illustrations of the time.

April Bell is a witch, part of the Old Breed that Mondrick wants to eliminate from the earth. Barbee, it turns out, is a shapeshifter himself. I thought is was cheating to have them turn invisible when they took animal form, but it is necessary to make the plot work. Because Williamson wanted to write science fiction and not occult fantasy, he provides some anthropological background for this demon breed and some fanciful physics for why they can walk through walls. This theory is put forth at length several times in dialogue that bears no hint of realistic human speech.

April Bell is a witch, part of the Old Breed that Mondrick wants to eliminate from the earth. Barbee, it turns out, is a shapeshifter himself. I thought is was cheating to have them turn invisible when they took animal form, but it is necessary to make the plot work. Because Williamson wanted to write science fiction and not occult fantasy, he provides some anthropological background for this demon breed and some fanciful physics for why they can walk through walls. This theory is put forth at length several times in dialogue that bears no hint of realistic human speech.

Williamson lists this among his favorite books because it embodied much of what he learned about himself in psychoanalysis. He had been selling erractically to the pulps for years, but in 1936 he hit a wall. (He was 28.) He had been reading about psychiatry and wrote Ives Hendricks , the author of Facts and Theories of Psychoanalysis about coming to Boston from New Mexico for treatment. Hendricks suggested the Menninger Clinic in Topeka and Karl Menniger agreed to see him on April 13. With enough money to live frugally in Topeka, even paying the five dollars an hour for treatment, Williamson stayed. He was under the treatment of Dr. Charles W. Tidd, until two years kater when money ran out and he and his doctor agreed there was nowhere further to go at the time.

In Darker Than You Think Topeka becomes Clarendon. Glennhaven is an enormous and very active psychiatric hospital where Barbee makes a brief stay. There is too much plot to keep him there for any length of time. What Williamson learned with Dr. Tidd at the Menninger was to let go of some of his inner conflicts and accept parts of himself he had attempted to keep rigidly separated. How this works out for Barbee in the novel some readers found shocking.

Darker Than You Think is enjoyable but dated and creaky. Here is a clue to how you might enjoy it more. Imagine it as a black and white movie from RKO studios in the 1940’s, produced by Val Lewton and directed by Jacques Tourneur. That is if you want to emphasize the moodier aspects. For a crisper image turn the project over to Robert Wise.

(All the biographical information in this review comes from Williamson’s memoirs, Wonder’s Child: My Life In Science Fiction.)

Full Details

Full Details