GMRC Review: Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his tenth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his tenth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Editor’s Note: Val posted this review two months ago and we missed adding it to the blog at that time.

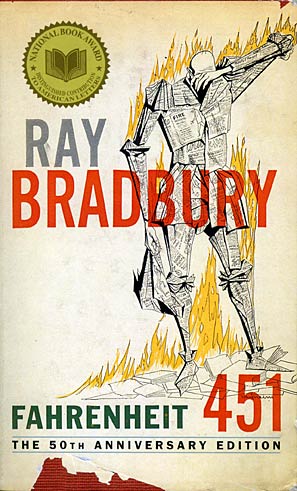

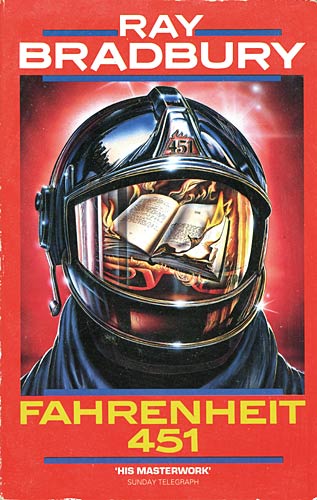

Last month I ran a poll to help me decide which book should be reviewed work number 300 on Random Comments and tied it to the Grand Master Reading Challenge for which I still have to read a couple of novels. Ray Bradbury won. I had expected one of the big names I hadn’t covered it to get it, perhaps Jack Vance or Robert Heinlein but, as one commenter pointed out, with Bradbury’s passing at the age of 91 just a few months ago, perhaps it is not so surprising he come out the favourite. I haven’t read anything by Bradbury before so I figured I’d read the book he is best known for. Fahrenheit 451 was published in 1953 so it’s too old to have won any of the major science fiction awards but it has been added to countless list of best books in science fiction and is well regarded outside the genre. It is one most influential dystopian novels, often mentioned in one breath with Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World. In short, a book with quite a reputation.

Last month I ran a poll to help me decide which book should be reviewed work number 300 on Random Comments and tied it to the Grand Master Reading Challenge for which I still have to read a couple of novels. Ray Bradbury won. I had expected one of the big names I hadn’t covered it to get it, perhaps Jack Vance or Robert Heinlein but, as one commenter pointed out, with Bradbury’s passing at the age of 91 just a few months ago, perhaps it is not so surprising he come out the favourite. I haven’t read anything by Bradbury before so I figured I’d read the book he is best known for. Fahrenheit 451 was published in 1953 so it’s too old to have won any of the major science fiction awards but it has been added to countless list of best books in science fiction and is well regarded outside the genre. It is one most influential dystopian novels, often mentioned in one breath with Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World. In short, a book with quite a reputation.

Fahrenheit 451 is a dystopian novel set in a future America where books are outlawed and a fireman’s job is to burn them instead of putting out fires. One such man is Guy Montag, who unquestionably burns books, the source of all dissent in society. Until he meets the 17-year-old Clarisse that is. She talks to him about ideas that make no sense and about doing things that no rational, we ll adjusted man should even consider. She makes Montag thing and without him understanding why, he develops an aversion against his job, starts questioning his life and develops a curiosity about books. Montag is in trouble.

They Have Not Seen the Stars

Ray Bradbury is known especially for his short stories and novels that blur the line between fantasy and horror, but not everyone knows that he published a collection of poetry (with nearly 500 pages of verse!) named after the poem below.

They have not seen the stars,

Not one, not one

Of all the creatures on this world

In all the ages since the sands

First touched the wind,

Not one, not one,

No beast of all the beasts has stood

On meadowland or plain or hill

And known the thrill of looking at those fires.

Our soul admires what they,

Oh, they, have never known.

Five billion years have flown

In turnings of the spheres,

But not once in all those years

Has lion, dog, or bird that sweeps the air

Looked there, oh, look. Looked there.

Ah, God, the stars. Oh, look, there!

It is as if all time had never been,

Nor Universe or Sun or Moon

Or simple morning light.

Those beasts, their tragedy was mute and blind,

And so remains. Our sight?

Yes, ours? to know now what we are.

But think of it, then choose. Now, which?

Born to raw Earth, inhabiting a scene,

And all of it no sooner viewed, erased,

As if these miracles had never been?

Vast circlings of sounding fire and frost,

And all when focused, what? as quickly lost?

Or us, in fragile flesh, with God’s new eyes

That lift and comprehend and search the skies?

We watch the seasons drifting in the lunar tide

And know the years, remembering what’s died.

SF/F Quotes: Ray Bradbury

“

Everyone must leave something behind when he dies, my grandfather said. A child or a book or a painting or a house or a wall built or a pair of shoes made. Or a garden planted. Something your hand touched some way so your soul has somewhere to go when you die, and when people look at that tree or that flower you planted, you’re there.

”

— Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 (1953)

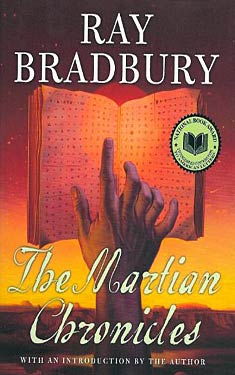

GMRC Review: The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury

Daniel Roy (triseult), has contributed over 30 reviews to WWEnd including this, his second, for the GMRC. Daniel is living his dream of travelling the world and you can read about some of his adventures on his blog Mango Blue.

Daniel Roy (triseult), has contributed over 30 reviews to WWEnd including this, his second, for the GMRC. Daniel is living his dream of travelling the world and you can read about some of his adventures on his blog Mango Blue.

There are SF books that age superbly well, staying relevant and believable decades beyond their publication dates. The Martian Chronicles is not such a book; it’s a delicate antique, the fossilized remains of dreams and terrors gone by, of a time when Mars had water irrigation canals, and everyone feared death by atomic war. It may not have remained relevant, but its lyrical beauty is intact.

Martian Chronicles is a series of loosely connected short stories set on the planet Mars; more specifically, on the planet Mars as it existed in the collective consciousness of the 1950s, when the lines slashed across its surface were water canals built by an ancient and alien civilization. In 2012, it reads not so much as science fiction, but as a form of dreamy fantasy, an alternate universe where the science fiction dreams of the Martian wild frontier are true. This gives a charming air of naïveté to the stories, a nostalgia of dreams gone by, made impossible by the images sent back by Viking and Pathfinder.

There exists a quaint notion in the public’s mind that a SF author’s greatness can be measured by his or her power to predict the future: much attention is given to Isaac Asimov anticipating the Laws of Robotics, or of Arthur C. Clarke having predicted orbital satellites. But reading The Martian Chronicles, it’s obvious that great SF writers do not so much try to anticipate and predict the future, but rather dream of all possible futures.

That’s what the stories in The Martian Chronicles feel like; a dream. They possess a dreamy, ethereal quality, the descriptions filled with a deep sense of wonder and joy at the Universe, a lyricism and poetry that depart in a formidable fashion from the dry intellectualism of Bradbury‘s contemporaries at the time. The stories themselves are enchanting, sometimes gripping; they never grow grim, even if they deal with death, yearning, sometimes murder, sometimes outright war. Some of the stories present arresting imagery to this day: the sight of all African Americans, having given up on ever being granted full civil rights, gathering their belongings and leaving for Mars; or the clockwork rhythms of an automated house, calling the children to breakfast long after Earth has died in an atomic war.

My biggest gripe with Martian Chronicles is the fate of the Martians themselves, and the relative lack of empathy given to what Bradbury imagined as beautiful, wise creatures. Their fate mirrors that of Native Americans, and perhaps because the novel was of its time, their destruction under the relentless wheels of colonization did not stir much sympathy in Mr. Bradbury. There was a huge opportunity to discuss the human/Martian cost of the American spirit of endeavor, but this is a theme which Mr. Bradbury has preferred should remain untouched.

My biggest gripe with Martian Chronicles is the fate of the Martians themselves, and the relative lack of empathy given to what Bradbury imagined as beautiful, wise creatures. Their fate mirrors that of Native Americans, and perhaps because the novel was of its time, their destruction under the relentless wheels of colonization did not stir much sympathy in Mr. Bradbury. There was a huge opportunity to discuss the human/Martian cost of the American spirit of endeavor, but this is a theme which Mr. Bradbury has preferred should remain untouched.

On a personal note, I began reading The Martian Chronicles on June 5th, 2012, unaware that Mr. Bradbury had passed away on that very day. By a strange twist of fate, despite having grown up with SF stories, I had never read any book by Mr. Bradbury before. I’m glad I finally, if a bit too late, learned to appreciate the greatness of his writings, and why so many authors consider him an inspiration.

When Mr. Bradbury passed away, Humanity has lost a dreamer. But judging by the beauty and grace of this book, the dreamer’s dreams live on.

Thank you, Mr. Bradbury (1920 – 2012)

Sad news today. Author Ray Bradbury died last night at the age of 91. Ray Bradbury is among the most celebrated, and perhaps even under-celebrated, science fiction authors. On the one hand, his masterpiece, Fahrenheit 451, appears on eight different "best of" lists, and the epic The Martian Chronicles is on seven. On the other hand, his novels never won a major science fiction award. His books have been alternately banned and required high school reading. Like many geniuses, many of his works have appreciated in value over time. Mr. Bradbury will write no more, but we are left with a body of work that I believe has only begun to show its relevance. Since I lack the eloquence to bid a proper farewell to such a great writer, I’ll let another great writer, Robert Louis Stephenson, do it for me:

Sad news today. Author Ray Bradbury died last night at the age of 91. Ray Bradbury is among the most celebrated, and perhaps even under-celebrated, science fiction authors. On the one hand, his masterpiece, Fahrenheit 451, appears on eight different "best of" lists, and the epic The Martian Chronicles is on seven. On the other hand, his novels never won a major science fiction award. His books have been alternately banned and required high school reading. Like many geniuses, many of his works have appreciated in value over time. Mr. Bradbury will write no more, but we are left with a body of work that I believe has only begun to show its relevance. Since I lack the eloquence to bid a proper farewell to such a great writer, I’ll let another great writer, Robert Louis Stephenson, do it for me:

Virgil of prose! far distant is the day

When at the mention of your heartfelt name

Shall shake the head, and men, oblivious, say:

‘We know him not, this master, nor his fame.’

Not for so swift forgetfulness you wrought,

Day upon day, with rapt fastidious pen,

Turning, like precious stones, with anxious thought,

This word and that again and yet again,

Seeking to match its meaning with the world;

Nor to the morning stars gave ears attent,

That you, indeed, might ever dare to be

With other praise than immortality

Unworthily content.

Thank you, Mr. Bradbury. You will be missed.

GMRC Review: Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including this latest review for the GMRC.

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including this latest review for the GMRC.

Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man and Fahrenheit 451 are two of the earliest SF books I remember reading, around age ten, probably because they were the only science fiction books on my parents’ shelves. Bradbury, then, and Asimov a little later, would be my “gateway drugs” into the genre, and I read everything I could find in the library by both authors at a young age. I remember liking both books, but preferring The Illustrated Man collection, and rereading Fahrenheit 451 today, I have to agree with my ten-year-old self that Bradbury is much better at shorter lengths. Not that Fahrenheit is very long—for a novel, it’s extremely short—but that only makes the limitation more obvious. A simple theme that works well as the basis of a short story can outstay its welcome in a novel, especially if the author fails to engage with the ambiguities and subtleties inherent in it. Much as I was looking forward to rereading this, I ended up surprisingly disappointed. What seemed profound and meaningful to me as a child, now comes across as a problematic and unsubtle screed about the dangers of conformity and mass media. The idea that “the majority,” if given its way, would stamp out individualism, seems unrealistic, and reads now like an unconvincing condemnation of communism. This is prime period Bradbury, however, so my arguments with the novel are often overcome by his striking images and the fascinating strangeness of the world he creates. (Spoilers follow, in case anyone hasn’t read this novel yet!)

Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man and Fahrenheit 451 are two of the earliest SF books I remember reading, around age ten, probably because they were the only science fiction books on my parents’ shelves. Bradbury, then, and Asimov a little later, would be my “gateway drugs” into the genre, and I read everything I could find in the library by both authors at a young age. I remember liking both books, but preferring The Illustrated Man collection, and rereading Fahrenheit 451 today, I have to agree with my ten-year-old self that Bradbury is much better at shorter lengths. Not that Fahrenheit is very long—for a novel, it’s extremely short—but that only makes the limitation more obvious. A simple theme that works well as the basis of a short story can outstay its welcome in a novel, especially if the author fails to engage with the ambiguities and subtleties inherent in it. Much as I was looking forward to rereading this, I ended up surprisingly disappointed. What seemed profound and meaningful to me as a child, now comes across as a problematic and unsubtle screed about the dangers of conformity and mass media. The idea that “the majority,” if given its way, would stamp out individualism, seems unrealistic, and reads now like an unconvincing condemnation of communism. This is prime period Bradbury, however, so my arguments with the novel are often overcome by his striking images and the fascinating strangeness of the world he creates. (Spoilers follow, in case anyone hasn’t read this novel yet!)

Memorable images abound: the woman who refuses to leave when the firemen arrive, preferring to burn with her books; the sensory overload of the “parlor families” and the “thimble-wasp” earplugs (Bradbury’s anticipation of people who are continuously attached to the iPods or cell phones); the stomach-pumping “suction snake” and the mechanical bloodhound, its hypodermic needle moving in and out; the city launched into the air as the homeless intellectuals can only stand and watch. The writing is florid at times, but his use of poetic language is one of the ways that Bradbury’s writing stands out, especially when compared to his fellow SF writers of the early ‘50s.

Bradbury’s rage at the dumbing-down of society is palpable, as he portrays the overwhelming distractions of media and advertising, contrasted with the social distaste for engagement with ideas and people, or for the simple pleasures of everyday existence. This alienation and repression leads to suicide becoming ever more commonplace, mirrored at the societal level by the easy acceptance of self-destructive war. “The Army said so. Quick war. Forty-eight hours they said, and everyone home. That’s what the Army said. Quick war… I’m not worried. It’s always someone else’s husband dies, they say.” (Sound familiar?)

Certainly most are already familiar with the novel’s premise: In the seemingly near future, extreme conformity is the primary value of American society. The role of “firemen” is no longer to put out fires. Buildings have been fireproofed and, in a memorably ironic role-reversal, firemen become fire-starters, responding to reports of secret stashes of illegal books, flamethrowers in hand. For the most part, Americans have not objected to the institutionalized book-burning, agreeing that the profusion of ideas found in them only serves to confuse and distract, creating a potential danger to society, along with discontent and melancholy among individual readers. Better by far to spend leisure time with the jabbering “family” that appears on the mind-numbing high-volume big-screen television programming that has taken the place of engagement with real people and ideas for the vast majority. The constant, gullibly-accepted media bombardment creates a population that no longer questions the decisions of the authorities, nor accepts that they would have the right to ask such questions.

Bradbury’s critique of anti-intellectualism resonates in today’s America, where a significant proportion of the population have no problem rejecting the expert scientific consensus on questions of meteorology and biology, and even refusing to “believe” easily verifiable facts, such as the birthplace and religion of the President. But Bradbury’s concern is not with this type of politically-abetted misinformation, but rather with the sort of dislike schoolchildren can have for the smart kid in the class. When Montag, the fireman protagonist, begins to show signs of questioning his role as a book-burner, his perceptive (and surprisingly well-read) superior, Captain Beatty, recites the party line to him:

“With schools turning out more runners, jumpers, racers, tinkerers, grabbers, snatchers, fliers, and swimmers instead of examiners, critics, knowers, and imaginative creators, the word ‘intellectual,’ of course, became the swear word it deserved to be. You always dread the unfamiliar. Surely you remember the boy in your own school class who was exceptionally ‘bright’ did most of the reciting and answering while the others sat like so many leaden idols, hating him. And wasn’t it this bright boy you selected for beatings and tortures after hours? Of course it was. We must all be alike. Not everyone born free and equal, as the Constitution says, but everyone made equal.”

But the response of Faber, a member of the book-preserving underground, sought out by Montag in his attempt to sort out his newly-discovered rebellious inclinations, also seems problematic: “But remember that the Captain belongs to the most dangerous enemy to truth and freedom, the solid unmoving cattle of the majority. Oh, God, the terrible tyranny of the majority.” But Bradbury isn’t concerned about religious or ethnic minorities; he’s upset that the intellectual minority has been marginalized, and implies that the result of such a “tyranny” of the masses would be a mind-numbingly conformist self-destructive dystopia. John Stuart Mill considered a similar possibility in responding to the new ideas of the Utopian (pre-Marxist) communists in 1848, which he saw as potentially stifling to individualism:

“The question is whether there would be any asylum left for individuality of character; whether public opinion would not be a tyrannical yoke; whether the absolute dependence of each on all, and the surveillance of each by all, would not grind all down into a tame uniformity of thoughts, feelings, and actions…. No society in which eccentricity is a matter of reproach can be in a wholesome state.”

Is Fahrenheit 451 yet another Cold War anti-communist tract? Consider the society Bradbury portrays: television is not just a diversion from more intellectual pursuits; rather, those who enjoy it are portrayed as utter morons. (And the fact that the only characters we see portrayed this way are women doesn’t help.) The complexities of modern urban societies are inherently harmful, with no positive aspects. The normal human urge to conform to a society is not just something to be guarded against, but something which results in mental illness and both individual and social suicidal behavior. It’s not that Bradbury doesn’t bring up a valid concern, and one with which I strongly sympathize, but his heavy-handed and unsubtle extrapolation of the negative aspects of media-driven conformity ultimately grows tiresome and unbelievable. In a short story like “The Pedestrian,” or even the novella “The Fireman,” from which Fahrenheit 451 was expanded, these themes come across as valuable food for thought; expanded to novel length, the lack of nuance starts to become problematic.

Is Fahrenheit 451 yet another Cold War anti-communist tract? Consider the society Bradbury portrays: television is not just a diversion from more intellectual pursuits; rather, those who enjoy it are portrayed as utter morons. (And the fact that the only characters we see portrayed this way are women doesn’t help.) The complexities of modern urban societies are inherently harmful, with no positive aspects. The normal human urge to conform to a society is not just something to be guarded against, but something which results in mental illness and both individual and social suicidal behavior. It’s not that Bradbury doesn’t bring up a valid concern, and one with which I strongly sympathize, but his heavy-handed and unsubtle extrapolation of the negative aspects of media-driven conformity ultimately grows tiresome and unbelievable. In a short story like “The Pedestrian,” or even the novella “The Fireman,” from which Fahrenheit 451 was expanded, these themes come across as valuable food for thought; expanded to novel length, the lack of nuance starts to become problematic.

This interpretation is driven home by the end of the novel, in which the seeming destruction of this society (and most of the population), while portrayed as tragic, also comes across as a sort of necessary cleansing, allowing humanity the hope of potentially going back to a more pristine state. Others may take this differently than I did, but blowing up the world and starting over precludes the possibility of reform or revolutionary change through less apocalyptic means. Bradbury seems to be saying that we brought this on ourselves by abandoning books and ideas in favor of mindless entertainment and meaningless sensory stimulation. We abandoned individualism for conformity and communism. As the cities burn, the non-conformist intellectuals, who have gone into semi-hiding in the countryside, are vindicated. America has not become a dystopia because of the imposition of tyranny by political, intellectual, or economic elites; rather, it is the tyranny of the majority. Democracy has gone too far.

One of the roles of dystopian fiction is that of the cautionary tale, extrapolating from current circumstances to show what might happen “if this goes on.” In this case, though, I think Bradbury undercuts his conclusion (and thus his warning) through his use of hyperbole, and by choosing to end the world without considering the possibility of reforming it. But this is a personal reaction. Others may respond positively to Bradbury’s ideas, and it brings up some fascinating issues that will always be with us. There are rewards to be had here, and there are reasons Fahrenheit 451 is considered a classic, and is commonly assigned in high school English classes. Any book that raises important issues and produces strong responses—either positive or negative—has value. The longer such debates go on, the less likely Bradbury’s future will be realized. And while I think that book-burning is more likely to arise from a tyranny of the few than from a tyranny of the majority, a good society will resist it, regardless of its origins.

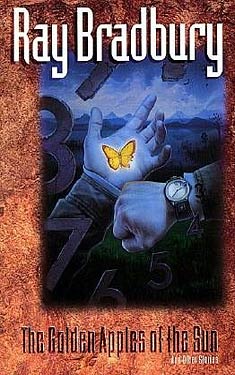

GMRC Review: The Golden Apples of the Sun and Other Stories

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s third featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s third featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun and Other Stories (1990) contains short stories from two of his previous works: one by the same name, published in 1953, and R is for Rocket, published in 1962. This reprint contains all of the stories from R is for Rocket and eighteen of the original twenty-two stories in the previous edition of Golden Apples. (The two collections had a couple of stories in both.)

Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun and Other Stories (1990) contains short stories from two of his previous works: one by the same name, published in 1953, and R is for Rocket, published in 1962. This reprint contains all of the stories from R is for Rocket and eighteen of the original twenty-two stories in the previous edition of Golden Apples. (The two collections had a couple of stories in both.)

The stories from the original Golden Apples demonstrate the range of Bradbury’s writing. Many of them were originally published in mainstream publications, such as The New Yorker, Esquire, The Saturday Evening Post, and Colliers, and don’t demonstrate any science fiction or fantasy elements. They do, however, convey a sense of wonder and otherness. Because of this, many of them were recycled for HBO’s 1980s series, Ray Bradbury Theater. The strongest of these stories seem very current. “I See You Never” recounts the deportation of a Mexican immigrant who had overstayed his visa. “Sun and Shadow” is set in Mexico and explores a poor homeowner’s objection to his house being used as “local color” in the photos of an American fashion photographer. The protagonist in “The Murderer” reacts to modern technology in the same way that many of us wish we could. The murderer in “The Fruit in the Bottom of the Bowl” worries about leaving evidence behind.

The weaker stories do seem very dated. Many of them have ambiguous time settings, placed in either our past or an isolated “land that time forgot” setting. For this reason, I did not like “The Great Wide World Over There” and “Powerhouse.” I found “The Big Black and White Game” particularly puzzling. In telling about a baseball game between the white and black employees of a resort hotel, Bradbury displays that type of 1940s racism that doesn’t think it is racist. He clearly wants to denounce the overt racism of the white women in the story, but then he has the following passage, which I think is supposed to be complimentary:

"How easily the dark people had come running first, like those slow-motion deer and antelopes in those African moving pictures, like things in dreams. They came like beautiful brown, shiny animals that didn’t know that they were alive, but lived. And when they ran and put their easy, lazy, timeless legs out and followed with their big sprawling arms and loose fingers, and smiled blowing in the wind, their expressions did not say, ‘Look at me run, look at me run.’ No, not at all. Their faces dreamily said ‘Lord, but it’s sure nice to run…’"

Many reviews of “The Big Black and White Game” commend Bradbury for writing a story about racial tensions. I also learned that the story was chosen for Best American Short Stories in 1945. This story provides a good example of the way a dated story can jar a reader. I had trouble reconciling the author of Fahrenheit 451 to the author of this story. (This experience is making me add The Martian Chronicles to my list. I’m ashamed to say that I’ve never read it, but I’ve always seen it characterized as a book that exposes prejudice and racism.)

The new edition of Golden Apples does not indicate that the reader is moving from the earlier The Golden Apples of the Sun to R is for Rocket, but it does include Bradbury’s 1962 introduction to the latter book. He writes: “This is a book then by a boy who grew up in a small Illinois town and lived to see the Space Age arrive, as he hoped and dreamt it would.” This “book” is much more cohesive than the earlier section containing the Golden Apples stories. It tells about rocket ships, space colonies, and time travel (intended and unintended, physical as well as mental). Many of the stories deal with family and space travel: “R is for Rocket” and “Rocket Man” charmingly demonstrate the sacrifices that families make when one of their members decides to travel to the stars; “The Strawberry Window” shows how colonists cope with being away from home. “The Sound of Thunder” is Bradbury’s eerie story that presents the “butterfly effect” though time travel. William Contento’s index lists this story as the most reprinted and anthologized science fiction story. “Frost and Fire” is a novelette-length story of survivors who crash on a planet with extreme temperatures and high radiation. At the beginning of the story, a boy, Sim, is born with all his faculties and senses intact. He has a clear racial memory telling him that he will grow and live and die in eight days. Bradbury’s structure and premise are strong here, and I found this story much more satisfying than many of the others.

The new edition of Golden Apples does not indicate that the reader is moving from the earlier The Golden Apples of the Sun to R is for Rocket, but it does include Bradbury’s 1962 introduction to the latter book. He writes: “This is a book then by a boy who grew up in a small Illinois town and lived to see the Space Age arrive, as he hoped and dreamt it would.” This “book” is much more cohesive than the earlier section containing the Golden Apples stories. It tells about rocket ships, space colonies, and time travel (intended and unintended, physical as well as mental). Many of the stories deal with family and space travel: “R is for Rocket” and “Rocket Man” charmingly demonstrate the sacrifices that families make when one of their members decides to travel to the stars; “The Strawberry Window” shows how colonists cope with being away from home. “The Sound of Thunder” is Bradbury’s eerie story that presents the “butterfly effect” though time travel. William Contento’s index lists this story as the most reprinted and anthologized science fiction story. “Frost and Fire” is a novelette-length story of survivors who crash on a planet with extreme temperatures and high radiation. At the beginning of the story, a boy, Sim, is born with all his faculties and senses intact. He has a clear racial memory telling him that he will grow and live and die in eight days. Bradbury’s structure and premise are strong here, and I found this story much more satisfying than many of the others.

In general, this collection seems uneven. There are great stories, weak stories, and dated stories—some are genre fiction; others are more mainstream. The R is for Rocket part is certainly stronger. The stories are better, and they seem to fit together. However, three of my four favorites come from the Golden Apple part of the book. These are “Sun and Shadow” and “The Fruit at the Bottom of the Bowl,” which are not science fiction stories at all, and “The Murderer,” which centers on technology in the “future” and seems very much like now. This book has made me want to read more Bradbury.

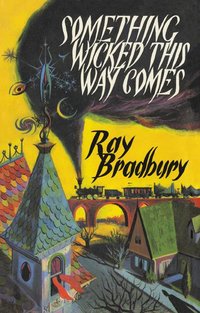

GMRC Review: Something Wicked This Way Comes

Well, you’ve got to grant that Ray Bradbury is not a boring novelist. The entire story of Something Wicked This Way Comes runs almost entirely on enthusiasm. Part morality tale and part freak show, Something Wicked finds something of a happy medium as an exuberant young adult novel, a wild and unstoppable train of delight in every moment of living. The two protagonists Jim and Will live unimpeded lives without any great danger until the day the Dark Train arrives in the middle of the night, at the witching hour. Unfortunately, Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show offers more than mere curiosities and entertainments: it offers your heart’s desire… for a price. Are you looking for true love? Your lost youth? Cooger & Dark will give it to you, just take a short ride on this carousel over here.

Well, you’ve got to grant that Ray Bradbury is not a boring novelist. The entire story of Something Wicked This Way Comes runs almost entirely on enthusiasm. Part morality tale and part freak show, Something Wicked finds something of a happy medium as an exuberant young adult novel, a wild and unstoppable train of delight in every moment of living. The two protagonists Jim and Will live unimpeded lives without any great danger until the day the Dark Train arrives in the middle of the night, at the witching hour. Unfortunately, Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show offers more than mere curiosities and entertainments: it offers your heart’s desire… for a price. Are you looking for true love? Your lost youth? Cooger & Dark will give it to you, just take a short ride on this carousel over here.

It’s easy for a reader to lose the overall geography of the novel in favor of its individual parts. Bradbury’s prose oozes with flamboyance and a baroque explosion of literary decoration. Consider this description of a library from the second chapter:

Out in the world, not much happened. But here in the special night, a land bricked with paper and leather, anything might happen, always did. Listen! and you heard ten thousand people screaming so high only dogs feathered their ears. A million folk ran toting cannons, sharpening guillotines; Chinese, four abreast, marched on forever. Invisible, silent, yes, but Jim and Will had the gift of ears and noses as well as the gift of tongues. This was a factory of spices from far countries. Here alien deserts slumbered. Up front was the desk where the nice old lady, Miss Watriss, purple-stamped your books, but down off away were Tibet and Antarctica, the Congo. There went Miss Wills, the other librarian, through Outer Mongolia, calmly toting fragments of Peiping and Yokohama and the Celebes. Way down the third book corridor, an oldish man whispered his broom along in the dark, mounding the fallen spices…

Arguably, the overall body of the novel takes second place to its members. Bradbury’s prose is such a delight to read that you might find yourself surprised to see a story wrapping itself up in the final chapters.

Arguably, the overall body of the novel takes second place to its members. Bradbury’s prose is such a delight to read that you might find yourself surprised to see a story wrapping itself up in the final chapters.

But what is this novel? A horror story? An allegory of sin and temptation? An exercise in literary gluttony? I would suggest that it’s a little bit of each. The moral, insofar as there is a coherent one at all, concerns the power of a sanguine attitude over the dark despair that comes in the middle of the night when you’re tossing awake in bed. The Dark People could be interpreted as embodiments of ennui or despondency, as noonday devils who twist one’s head around backwards to glare forever at what he has left behind. They feed on the unhappiness of ordinary people, and have so fed for centuries if not millennia.  The fact that laughter has such great power over Mr. Dark and his carnival freaks would support this approach to the story.

The fact that laughter has such great power over Mr. Dark and his carnival freaks would support this approach to the story.

Most of all, I think that Something Wicked is worth reading for its grab-life-by-the-tail-and-hang-on attitude. It lacks a certain type of literary quality, but makes up for it with spiritedness, like a child who creates a whole imaginative universe using only Legos and crayons. One might need to be in the right mood for this novel, but it’s not an unpleasant mood. Not unpleasant at all.

The Martian Chronicles: Essential and Still Relevant

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. Check out his review of one of the all-time classics of SF below and help us welcome him to WWEnd. Thanks, Scott!

It was fascinating to return to The Martian Chronicles over three decades after first reading it. (Ray Bradbury was the first SF writer I read as a child.) It remains beautiful, relevant, and unique.

It was fascinating to return to The Martian Chronicles over three decades after first reading it. (Ray Bradbury was the first SF writer I read as a child.) It remains beautiful, relevant, and unique.

Bradbury, in a series of linked short stories, presents the history of the exploration of Mars and the subsequent emigration and abandonment of the planet by humanity. The stories include rockets, robots, and Martians, but Bradbury clearly has no interest in scientific extrapolation regarding these SF tropes. Instead, they are used as plot device or metaphor to get at his real concerns about the state of humanity (Americans, especially), at the time he wrote these stories. In fact, if you think too much about the literal events of the book, it won’t work for you. The first Mars expeditions made up in part of yahoos who get drunk and vandalize ancient Martian artifacts? Thousands of people colonizing Mars within a couple of years of the earliest explorers reaching it, bringing with them all the trappings of life on Earth? Almost the entire human population of Mars returning en masse after seeing their home planet on fire as the result of a nuclear war?

Yet these events seem almost foreordained in the context of Bradbury’s themes, which include cultural and racial intolerance, imperialism, humanity’s propensity for violence, the consequences of ignorance, the repression of individuality, and the inability of people to learn from history. Yes, it’s a laundry list of cold war alienation, but the issues take on added relevance and added interest in the SF context. It seems that, for Bradbury, technology merely gives humanity’s unfortunate tendencies new venues in which and tools with which to manifest themselves. The arrival of humanity spreads Earth’s (actually, America’s) culture to Mars, wiping out the Martians in the process through the spread of disease–a point reminiscent of what happened to the Native Americans. Book censors and hot dog stands are not far behind…

The telepathic Martians take on different roles in different stories, serving mainly as metaphor rather than character. They serve alternately as victim, nightmare, conscience, oracle, empath, and mirror. They are projections of us and, at the end of the book, we must become them, if there is to be a future for humanity.

The telepathic Martians take on different roles in different stories, serving mainly as metaphor rather than character. They serve alternately as victim, nightmare, conscience, oracle, empath, and mirror. They are projections of us and, at the end of the book, we must become them, if there is to be a future for humanity.

Not every story is up to the level of the half-dozen classics in the book, but each does make a contribution to the theme. The format allows Bradbury to make use of his forte–the emotional punch of the short story–while building theme and resonance as in a novel. When I began rereading, I suspected that The Martian Chronicles might not be as good as I remembered, but I think it may be even better, though in ways I probably didn’t see back in the ’70s. Other Bradbury short stories from the late ’40s and ’50s reach the same heights as those in this book, but the added resonance of the links between them makes this the essential Ray Bradbury book. An enduring contribution to SF and to American literature!

Full Details

Full Details