LeGuin Documentary Starts Kickstarter Campaign

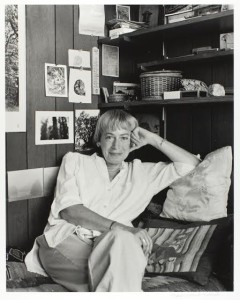

Documentary filmmaker Arwen Curry has worked seven years assembling footage for Worlds of Ursula K. LeGuin. Curry has produced significant documentaries on Susan Sontag and the California architect and designer Charles Eames, but this is her most personal project. She grew up immersed in LeGuin’s fiction, and for this film she has traveled with the author to the many landscapes that inspired her fantastic worlds. Along the way she learned just “how deeply Le Guin’s otherworldly made-up places are informed by real places in the real world. She’s a very rooted writer, and person.”

Documentary filmmaker Arwen Curry has worked seven years assembling footage for Worlds of Ursula K. LeGuin. Curry has produced significant documentaries on Susan Sontag and the California architect and designer Charles Eames, but this is her most personal project. She grew up immersed in LeGuin’s fiction, and for this film she has traveled with the author to the many landscapes that inspired her fantastic worlds. Along the way she learned just “how deeply Le Guin’s otherworldly made-up places are informed by real places in the real world. She’s a very rooted writer, and person.”

This film gives us a chance to hear the LeGuin’s voice recounting her “journey of self-discovery as she comes into her own as a major feminist author, inspiring generations of women and other marginalized writers along the way.” Curry also brings in commentary by such figures as Margaret Atwood, Samuel R. Delany, and Karen Joy Fowler.

The National Endowment for the Humanities awarded Worlds of Ursula K. LeGuin a production grant, but those funds will not be released until the filmmakers raise a remaining $80,000. A Kickstarter campaign began on Februrary 1 and runs through the end of the month. It’s a chance to participate in a project that will help define the central role science fiction and speculative literature plays in American society.

Use this link to access the Kickstarter campaign.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/arwencurry/worlds-of-ursula-k-le-guin

GMRC Review: Always Coming Home by Ursula K. Le Guin

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted man fine reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted man fine reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

To borrow from the title of one of the first sections of Always Coming Home, this book is an “archaeology of the future.” I purposely use the term book rather than novel, since the structure of Ursula K. Le Guin‘s 1985 work makes it more of a collage than a narrative, though it does tell a story, and it certainly has a theme. The story is that of an entire people—the Kesh, the People of the Valley, living in the far distant future somewhere in Northern California. A changed climate has created an inland sea east of the Valley, and the people who live there are still dealing with the legacy of the chemical wastes left behind by a long-gone civilization whom the Kesh think of as people “who lived outside the world” and whose poisonous lifestyle has led to their being remembered in legends and visions as people who (literally) had their heads on backwards.

To borrow from the title of one of the first sections of Always Coming Home, this book is an “archaeology of the future.” I purposely use the term book rather than novel, since the structure of Ursula K. Le Guin‘s 1985 work makes it more of a collage than a narrative, though it does tell a story, and it certainly has a theme. The story is that of an entire people—the Kesh, the People of the Valley, living in the far distant future somewhere in Northern California. A changed climate has created an inland sea east of the Valley, and the people who live there are still dealing with the legacy of the chemical wastes left behind by a long-gone civilization whom the Kesh think of as people “who lived outside the world” and whose poisonous lifestyle has led to their being remembered in legends and visions as people who (literally) had their heads on backwards.

The Kesh civilization may be the ultimate working out of Le Guin’s utopian ideals. Her best-known science fiction novels—The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed—both posit alien societies that encourage readers to consider alternative gender roles and economic systems. Her subtitle for The Dispossessed—”An Ambiguous Utopia”—could apply just as well to Always Coming Home. The inability of the Kesh to comprehend a society like ours is due to their commitment to a post-industrial environmentally sustainable way of life (though they would never use such terminology, thinking of themselves as merely “living in the world”). That way of life—reminiscent of a settled Native American culture—is centered on a compatibility with nature. Nothing is taken that is not needed. The wealthiest are those who give the most, not those who accumulate possessions. A low human population density is scrupulously maintained. Communities are organized around both families and occupations, with each individual encouraged to pursue the work most amenable to her. Everyone works, and labor is not resented. Authority is entirely decentralized, and sexism is nonexistent. The Kesh are aware of the possibility of more advanced technologies, but choose not to pursue them, failing to see the point, and unwilling to sacrifice their environment. Their society works, and the reader understand why they would see us as “backward-heads.” As in the other two novels mentioned above, Le Guin invites the reader to question our own society by asking us to consider the possibility of a workable alternative. One of the great attractions of science fiction is its ability to encourage us to consider how things could be different, and Le Guin does this masterfully in Always Coming Home, though not in a way that science fiction readers are used to.

GMRC Review: The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

Daniel Roy (triseult), has contributed over 50 reviews to WWEnd including this, his fourth GMRC review to feature in the WWEnd blog. Daniel is living his dream of travelling the world and you can read about some of his adventures on his blog Mango Blue.

Daniel Roy (triseult), has contributed over 50 reviews to WWEnd including this, his fourth GMRC review to feature in the WWEnd blog. Daniel is living his dream of travelling the world and you can read about some of his adventures on his blog Mango Blue.

Calling this book “perfect” would do it an injustice. Its brilliance is not so much in meeting SF standards, but in exceeding them and leaving them far behind.

Calling this book “perfect” would do it an injustice. Its brilliance is not so much in meeting SF standards, but in exceeding them and leaving them far behind.

The Dispossessed is a complex novel. It’s not complex in terms of structure or themes; it’s not a hard book to read. Quite the opposite. But it manages to touch on so many aspects of the human experience at once that it’s hard to sum up what makes it so fascinating.

At the heart of it all is Shevek. Shevek, so complex and delightful to read. Shevek’s a hero, an outcast, a brilliant physicist, an idealist, an alien, a father, a lover, and a bit of a goof. He’s so many things at once that the only word to describe him is real. He anchors the whole story, brings it to life, fills it with emotion and thought. Through Shevek, Le Guin explores a plethora of themes: anarchism, politics, science, inspiration, love, responsibility, injustice, freedom. He’s the most realistic and inspirational fictional scientist I have ever read, and yet there is still time for him, in a mere 300 pages, to be a caring father and a poignant lover. Shevek’s awesome.

Some readers see in this book a plea for anarchism. I like the political theory, especially Noam Chomsky’s take on it, which he calls social libertarianism. By tackling anarchism, Ursula Le Guin is doing what SF should aspire to do every time: she explores a Great Idea, playing with it to see if it’s possible. In that sense, yes, she gives anarchism center stage, and gives it the space to make its plea. But I don’t think she set out to write a straight-up inspirational Utopia. Anarres doesn’t sound like such a great place to live.

The utopia of The Dispossessed is Shevek, not Anarres. Anarres’ brand of anarchism is broken, bogged down by the usual power struggles and human pettiness. Anarres forgot that a revolution must continue, lest it becomes the new order. The real anarchist revolution of this story is Shevek. He is a stranger in his own home, and he exiles himself to another world to find it again. In so doing, he touches both worlds in unexpected ways–and far beyond.

The utopia of The Dispossessed is Shevek, not Anarres. Anarres’ brand of anarchism is broken, bogged down by the usual power struggles and human pettiness. Anarres forgot that a revolution must continue, lest it becomes the new order. The real anarchist revolution of this story is Shevek. He is a stranger in his own home, and he exiles himself to another world to find it again. In so doing, he touches both worlds in unexpected ways–and far beyond.

I can already see that this first read of The Dispossessed won’t be my last. This is SF of the first order, one that enriches my own world by its mere existence as a thought experiment. And besides, I have a feeling I’ll miss Shevek if we spend too much time apart.

GMRC Review: Lavinia by Ursula K. Le Guin

Glenn Hough (gallyangel) is, among other things, a nonpracticing futurist, an anime and manga otaku, a gourmet, a writer of science fiction novels which don’t get published to world wide acclaim, and is almost obsessive about finishing several of the lists tracked on WWEnd. This is Glenn’s first featured review for the GMRC.

Glenn Hough (gallyangel) is, among other things, a nonpracticing futurist, an anime and manga otaku, a gourmet, a writer of science fiction novels which don’t get published to world wide acclaim, and is almost obsessive about finishing several of the lists tracked on WWEnd. This is Glenn’s first featured review for the GMRC.

This is a tale of a footnote. Much like Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, which looks up at the wide world of Hamlet from the POV of minor characters, Lavinia immerses us in the world of Vergil’s Aeneid from the POV of a woman even further removed from the central action. In the Aeneid, Lavinia is named, she plays a role, a war is fought over her marriage rites since she was being used as a political tool, but yet, she never speaks a word in the poem.

Vergil renders her mute.

Le Guin has now given her a voice.

In terms of presentation, Le Guin’s Lavinia occupies middle ground. It is not the epic ground of heroes and jealous gods that is the backbone of Vergil’s Aeneid. The gods in Lavinia have lost their mythic stature. They are now gods of woods, auguries, the hearth, the storehouse. Gods that are a backbone of life but not humanized master movers. Nor is this book a realist exploration of barbaric bronze age peoples, based in what little archaeology, anthropology and the stories, myths, and lies which is all the historians have of the age. Middle ground. Barbarous yes, but gentled. Epic heroes, not quite, but these are the root cultures which founded Rome. And the seeds of that coming glory are present.

As the novel opens and we are drawn into this culture, we quickly see the parallels between two well known Greek ladies: Helen and Cassandra. Like Helen, a war is found over her. Helen gave of herself, Lavinia withheld herself. Like Cassandra, Lavinia had foresight. But instead of speaking and not being believed, Lavinia keeps the knowledge to herself. Lavinia has to act this way since the poet gave her no lines in his poem. For in vision quests performed at a sacred sulfur spring, Lavinia meets the dying Vergil. He is a shade, a shadow, filled with grief over his poem which is unfinished and incomplete. He morns his lack of attention concerning Lavinia. It is from Vergil that Lavinia learns her future, the long litany of deaths which are committed in her name, and the knowledge of a son which is a sire to kings, which lead to the greatness of Rome.

As the novel opens and we are drawn into this culture, we quickly see the parallels between two well known Greek ladies: Helen and Cassandra. Like Helen, a war is found over her. Helen gave of herself, Lavinia withheld herself. Like Cassandra, Lavinia had foresight. But instead of speaking and not being believed, Lavinia keeps the knowledge to herself. Lavinia has to act this way since the poet gave her no lines in his poem. For in vision quests performed at a sacred sulfur spring, Lavinia meets the dying Vergil. He is a shade, a shadow, filled with grief over his poem which is unfinished and incomplete. He morns his lack of attention concerning Lavinia. It is from Vergil that Lavinia learns her future, the long litany of deaths which are committed in her name, and the knowledge of a son which is a sire to kings, which lead to the greatness of Rome.

To me, Lavinia’s relationship to the poet Vergil and her knowledge that she is a character in his poem is the most interesting aspect of the book. Lavinia is bound by the limitations Vergil gives her, but fills that space with life, her life; the life of a daughter of a king, wife to the exiled Trojan Aeneas, who has taken up kingship in what will become Italy, mother and grandmother to kings. She is a queen. Since Vergil gave her no lines, little life and no death, in the end Lavinia too does not die. Her body passes but Lavinia lingers in the quiet places of her country. Her immortality is forever linked to the written word of the poet. While Vergil’s words live, Lavinia lives. While Le Guin’s words live, Lavinia lives.

Highly recommended.

GMRC Review: The Wind’s Twelve Quarters by Ursula K. Le Guin

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his sixth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his sixth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

The Wind’s Twelve Quarters is Ursula K. Le Guin‘s first collection of short fiction and was published in 1975. Quite unusual for a single author short science fiction collection, it is still in print decades after it has been first published. It is generally regarded as the strongest of her collections of short fiction. Not having read the others, I don’t have an opinion on that but I did think The Wind’s Twelve Quarters is a bit of a mixed bag. It contains a total of seventeen stories, presented more or less in the order they were published and cover the period between her first publication in 1962 and 1974, by which time she had published some of her best know and most critically acclaimed novels. Le Guin chose this order so the reader could experience her growth as an author. In that respect the collection certainly succeeds. The later stories are much stronger than the earlier ones. Most of the stories have a short introduction by Le Guin about the inspiration for the story and the editorial changes compared to the original magazine publications. A fair number of stories in the collection are what Le Guin calls psychomyths. These stories are hard to pin down but they are independent of setting and often have a surreal quality to them. Le Guin herself puts it like this:

…more or less surrealistic tales, which share with fantasy the quality of taking place outside any history, outside of time, in that region of the living mind which – without invoking any consideration of immortality – seems to be without spatial or temporal limits at all.

Le Guin on psychomyths – Foreword

Most of the stories that are not tied to her novels seem to fall into this category. Quite a few of the stories are linked to her novels though. There are Earthsea stories in this collection as well as stories set in the Hainish universe and even a story tied to her novel The Dispossessed (1974). The opening story, "Selmy’s Necklace" (1964), is essentially the prologue of Le Guin’s first novel, Roccanon’s World (1966). It is set in her Hainish future history and in some ways, reminded me a lot of some of Poul Anderson‘s Technic Civilization stories. It is seen mostly form the point of view of a member of a less technically advanced race trying to retrieve an heirloom that that was lost decades ago. She doesn’t properly comprehend the consequences of her request to be allowed to visit the aliens but to the reader the tragedy that is unfolding is quite clear. A science fiction story written in language that is more often found in fantasy. This story clearly shows why Le Guin usually doesn’t make too rigorous a distinction between the two.

The second story is "April in Paris" (1962) is the earliest story in the collection and Le Guin’s first sale. I can’t say I liked it much. I guess you could say it is a time travel story. I thought it was pretty predictable with more than a bit wish fulfilment in it. Le Guin then moves on to a story that is also a bit predictable but conceptually more interesting. "The Masters" (1963) deals with a man who is brought up in a very strict guild like environment where things have always been done a certain way and where deviating from this way, or trying to improve upon it, is heresy. He can’t resist the lure of progress though. There is another story that is thematically related to this one in the collection. "The Masters" is very dark, full of despair. Stylistically probably not the strongest piece but certainly an interesting one. "The Darkness Box" (1963), like "The Masters" is a piece that can be considered a fantasy or perhaps an early psychomyth. It’s a story with a sense of inevitably about it, of pointless repetition. Not a story that makes one feel happy although one of the characters sees things differently.

"The Word of Unbinding" and "The Rule of Names" (both 1964) are Le Guin’s first Earthsea stories. I haven’t read any of the Earthsea novels so putting them into the perspective of the whole series is going to be a bit difficult. I think they lay the groundwork for the system of magic found in the Earthsea novels. A system that appears to be quite sophisticated judging from these few pages. The stories are uncut fantasy, the only ones in this collection. I will have to read one of the Earthsea novels to be sure but I think I prefer Le Guin’s science fiction. Still, Earthsea is on the to read list.

"Winter’s King" (1969) is another story tied to one of Le Guin’s novels. It is set on the same planet as The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), a novel in the Hainish cycle that is also on my to read list. The version in this collection has been changed to fit the novel more closely and features the wintry world of Gethen. Le Guin plays with titles and particular pronouns to underline the androgyny or the inhabitants. The story itself is one of mind control and a King struggling to do what is best for the kingdom. It certainly makes me curious about the novel. Gethen seems like an intriguing place and the way gender appears to play no role in society opens up all kinds of interesting possibilities. Something that struck me about this story is how, like in "Selmy’s Necklace", Le Guin presents a technologically less advanced society in a science fiction story. Some readers would say there is a hint of fantasy in this story.

"The Good Trip" (1970) is a story that is probably contemporary. As the title suggests it is about drug use among other things. The trip makes it quite a strange story full of weird cognitive leaps and odd situations. Le Guin didn’t seem to be opposed to people experimenting with LSD at the time, which was no doubt frowned upon. She does mention in the introduction that she feels that "people who expand their consciousness by living instead of taking chemicals usually come back with much more interesting reports of where they’ve been." Now there is a bit of wisdom for you.

"Nine Lives" (1969) is one of the longer pieces of the collection and is a classic science fiction story. One that explores the possibilities of a new technology, in this case cloning. Le Guin studies the bond between genetically identical individuals, who shared most of their formative years and education and have been brought up to function as a team. The idea is disturbing on many levels. These people are a product, designed to outperform ordinary humans but also to be so self sufficient that without each other, they’d be lost. In a way, it is a barrier to get ideas of their own, which of course Le Guin can’t help but challenge. As with the best science fiction stories, this one contains plenty of food for thought.

The next story, "Things" (1970) is another psychomyth. I guess you could say it is about a man who has to take the last leap. It is beautifully written but personally I think it doesn’t quite take that many words to convey the message. Le Guin creates quite an elaborate setting. One which could have been explored in more detail, but Le Guin takes the story in another direction and much of the setting ends up being only marginally relevant to the story. This one was a miss for me. The collection continues with "A Trip to the Head" (also 1970). All I have to say about this, is that it went right over my head. I guess Le Guin’s writing is too intelligent for me sometimes.

What follows is the story with the most beautiful title in the collection. "Vaster Than Empires and More Slow" (1970) is a story in the Hainish Cycle, covering the lonely journey of a ship of explorers. Given the nature space travel at relativistic speeds, they give up everything they’ve known to go on this journey. Something not everybody is willing to do. The crew consists of misfits, people who have nothing to loose and the occasional completely dysfunctional character. A recipe for trouble and indeed, the first planet they survey, puts them to the test. This again is pretty straight forward science fiction, with perhaps a touch of horror. Or suspense if you will. I liked it a lot but it is not outstanding.

What follows is the story with the most beautiful title in the collection. "Vaster Than Empires and More Slow" (1970) is a story in the Hainish Cycle, covering the lonely journey of a ship of explorers. Given the nature space travel at relativistic speeds, they give up everything they’ve known to go on this journey. Something not everybody is willing to do. The crew consists of misfits, people who have nothing to loose and the occasional completely dysfunctional character. A recipe for trouble and indeed, the first planet they survey, puts them to the test. This again is pretty straight forward science fiction, with perhaps a touch of horror. Or suspense if you will. I liked it a lot but it is not outstanding.

"The Stars Below" (1973) explores in a bit more depth, one of the themes we also encountered in "The Masters". Scientific curiosity clashes with custom or religion and ends in violence. Where "The Masters" deals with the event itself, this story shows us the aftermath. An astronomer who’s instruments were destroyed hiding in an abandoned mine from his tormentors. It is a tragedy, even when he finds something to replace his interest in the stars. A moving story. I thought it was one of the better ones in the collection.

The collection continues with another science fiction story that is unrelated to a novel. "The Fields of Vision" (1973) about a group of astronauts who discover a strange city, for lack of a better word, on Mars that messes with their perceptions. One of them does not survive the trip back, the other two have lasting problems with their sense of hearing and sight. Their adjustment to this situation takes very different routes. I liked how Le Guin linked our perceptions with religious experiences in this story, and how much our brain relies on what our senses tell us. Most people trust what their senses tell them without question. In this story the characters know the input they are receiving is somehow changed. The author depicts this as quite a scary experience.

The next story is a very short, to the point science fiction story in which the main character is a tree. "Direction of the Road" (1974) is a highlight in the collection for me, a brilliant little story about relativity. It would spoil the story to say anything about the plot but it is such a strange reversal of how we think the world works, that I just had to read this story again right after I finished it. If I had to pick a favourite, this story might well be it.

For "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" (1974), Le Guin received a Hugo Award as well as a nomination for the Locus Award. It is another psychomyth, perhaps the one closest to the loose definition Le Guin put in the foreword to this collection. The story is very abstract in a way, no details on the setting (the author basically tells us to imagine our own), or characters are given. The story revolves around a scapegoat, one who is necessary to keep the rest of society happy. Once again a disturbing thought. One, as the story points out, not everybody can live with.

The final story of the collection is also one of the strongest ones. "The Day Before the Revolution" (1974) won a Nebula and a Locus award and was nominated for a Hugo. The story is tied to the novel The Dispossessed, a novel that I still consider to be one of the best in science fiction. It’s main character is Odo, who is a historical figure in the novel, the inspiration for the anarchistic society on Anarres. She may be honoured after her death but the life of a revolutionary is not easy. The story shows us an ageing Odo, full of grief and a premonition of death. The subtitle of The Dispossessed is An Ambiguous Utopia and this story is another expression of it. Odo achieved a lot but at a high price. I love the final paragraph of this story. As far as I am concerned, it should have won that Hugo too.

The Wind’s Twelve Quarters ends on a high, that is for sure. Some of the stories in this collection are no doubt among the best Le Guin as produced. All things considered, it isn’t one of those very rare collections that manage a consistently high quality though. It is a collection that shows Le Guin’s style, themes and development as a writer however. With links to her most important works and some award winning stories, perhaps it is not so strange this collection has been in print for more than three decades. I would not recommend someone with an interest in Le Guin’s work to start here, it is probably better to have read a few novels first, but for the real fan it is definitely a must read.

GMRC Review: Rocannon’s World by Ursula K. Le Guin

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s third GMRC review in our blog.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s third GMRC review in our blog.

Rocannon’s World is Ursula K. LeGuin‘s first published novel and is the first of her novels I have read. I’ve always thought that if I read Le Guin I would read The Left Hand of Darkness, since it was the big prize winner and the one everyone read back in the 1970’s, during the years after it first appeared and Le Guin’s reputation was on the rise. But I was not reading SF at that time, so I had only minimal interest, and, even worse, the novel always came with the dreaded recommendation, "No, even if you don’t like science fiction you are going to love this book." So I never read anything and only now, with both a renewed interest in SF and a self-directed tour through those writers who have earned Grand Master Status from the Science Fiction Writers of America, am I discovering the pleasures of her prose and storytelling.

Having decided to dive in, I headed straight for Left Hand but saw that it was the fifth novel in something called The Hainish Cycle. I like to start at the beginning, and in the Le Guin omnibus edition I got from the library, Rocannon’s World was a tempting ninety pages long. I didn’t know until after I finished and enjoyed it that in fact there are two chronologies to the Hainish Cycle, the order written and the order in which the stories occur. I could have started anywhere, since in some cases a millennium passes between narratives, but I still like the idea to seeing how Le Guin’s writing and sense of her future world develops in the real time of her composition.

Ninety pages, but since I was reading a bargain omnibus edition they were longish pages. Rocannon is still a short novel, only 144 pages in its PB editions. But in those few pages, and in her first novel, Le Guin creates an small-scale epic, both a classic quest tale and a story that spans several generations.

On the planet Formalhaut II, as the advanced space lords refer to the novel’s local, the culture is medieval and, unusual for all the inhabited worlds they investigate, there are multiple HILF’s, Highly Intelligent Life Forms. In the prologue, Semley, child of an ancient family wedded to the Lord of Hallam, endures the fallen estate of her family — good name but short of wealth. In a culture where display of wealth assures rank she sets out to retrieve a magnificent jewel that has somehow left the family treasure and been traded back to the Clay People who mined it. Within the first dozen pages, Semley has left her home, recruited the aid of the charming Kirien people and journeyed to the altogether less engaging caves of the Clay People. That this journey is made on large flying cats is likely to be the first narrative hurdle for readers who like their SF harder than softer. The hints of hard SF occur when the Clay People enter the action. Grungy and unappealing as they are, they live in underground cavern’s equipped with electric light and railways.

When Star Lords investigate new planets with multiple HILF’s they choose a species most likely to accept the technological head starts that will prepare them to join the League of all Planets. The Clay People have won out on Formalhaut II. They even have a space ship, into which they bundle Semley for transport to the planet where her jewel now rests in a museum of interplanetary artifacts. There she catches the eye of Rocannon, an anthropologist employed by the League, and he easily arranges for the return of the jewel. (This was written in 1966, and I wonder when the controversies over the return of imperialist plunder from European museums began to take shape.)

Upon return to Formalhaut II, Semley understands the consequences of her journey. In Le Guin’s universe, FTL travel is only possible in unmanned spacecraft. Although Semley feels her trip has taken no more than a year, she returns to a home where her husband and mother-in-law have been dead for a decade and her children are grown. Her courageous and adventurous journey has secured her nothing more than a long, solitary life.

That took me almost as long to tell as it does Le Guin, but it sets up the story of Rocannon’s establishment decades later of a base of Formalhaut II. We learn of this base only as it is destroyed, along with Rocannon’s survey team and all the work they have done. The universe is in a constant state of war preparedness, but this attack seems to have been sabotage, the first signs of divisions within The League of All Planets. Rocannon, unable to communicate with his own people, learns from satellite surveys that the enemy has established a base in the still unexplored Southern Continent. He puts together his own plucky crew of various species and it is back onto the flying cats.

That took me almost as long to tell as it does Le Guin, but it sets up the story of Rocannon’s establishment decades later of a base of Formalhaut II. We learn of this base only as it is destroyed, along with Rocannon’s survey team and all the work they have done. The universe is in a constant state of war preparedness, but this attack seems to have been sabotage, the first signs of divisions within The League of All Planets. Rocannon, unable to communicate with his own people, learns from satellite surveys that the enemy has established a base in the still unexplored Southern Continent. He puts together his own plucky crew of various species and it is back onto the flying cats.

This is a quest adventure, that without Rocannon’s, or more properly, Le Guin’s eye for anthropological detail and interesting world building, would slide into adventure fantasy of a most ordinary sort. But the swiftness of her writing, the predicaments she creates for her believable multi-species characters, and also her willingness to kill off so many protagonists kept me wrapped up in a narrative that seemed much larger than its ninety pages. Before his departure, an aging Semley gives Rocannon her precious jewel, should he need it along the way. And so this absurd, medieval artifact remains as crucial to the story as the special body suit Rocannon has on hand that although it makes him appear naked allows him to survive fire and torture.

When men like Rocannon join the star service, they know they are abandoning anything resembling a normal life of family or human contact. They may age slowly and inexorably as they poke about the universe, but centuries will pass on earth. Although contacts with home can be accomplished with a device capable of instantaneous communication across 120 light years, they have volunteered to become exiles in the name of science. It’s the respect Le Guin feels for their choices and the fundamental loneliness of their existence that give the novel its emotional depth. And I liked the flying cats.

GMRC Review: The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fourth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fourth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Many of the GMRC reviewers have noted that some books seem very much of their times. In fact, I commented in my review of Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun that several of his stories seemed dated. In reference to Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest, no observation could be more untrue. The novella upon which the novel is based won both the Nebula and Hugo Awards in 1973. The novella appeared in Harlan Ellison’s second New Wave anthology Again, Dangerous Visions in 1972. Le Guin published the novel version in 1976. However, with its focus on ethnic and ecological concerns, it seems as if it could have been written last year.

Many of the GMRC reviewers have noted that some books seem very much of their times. In fact, I commented in my review of Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun that several of his stories seemed dated. In reference to Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest, no observation could be more untrue. The novella upon which the novel is based won both the Nebula and Hugo Awards in 1973. The novella appeared in Harlan Ellison’s second New Wave anthology Again, Dangerous Visions in 1972. Le Guin published the novel version in 1976. However, with its focus on ethnic and ecological concerns, it seems as if it could have been written last year.

The novel takes place in New Tahiti Colony, on the planet Athshe. Terran workers have come to this tree-covered planet to harvest the trees and return them to Earth, which is mostly barren. In comparison, “New Tahiti was mostly water, warm shallow seas broken here and there by the reefs, islets, archipelagoes, and the five big Lands that lay in a 2500-kilo arc across the Northwest Quarter-sphere. And all those flecks and blobs of land were covered with trees. Ocean: forest. That was your choice on New Tahiti. Water and sunlight, or darkness and leaves” (15-16). Because this is one of Le Guin’s Hainish novels, the planet’s population was seeded by the Hains centuries earlier. The indigenous population are, of course, forest dwellers, but they took a very different evolutionary turn than their “cousins” the Terrans. The Athsheans are about a meter high with green fur. They look much like monkeys. The Athsheans have complex sleeping patterns, which involve multiple “naps” and lucid dreaming. The Terrans misinterpret the Athsheans’ biorhythms. At first they think that the Athsheans will make good slaves or members of the Voluntary Autochthonous Labor Corps (their euphemism) because they don’t sleep. Later the Terrans think that the Athsheans are lazy because they don’t realize that their “Voluntary Autochthonous Laborers” are napping rather than just sitting still and staring into space. This behavior leads the Terrans using verbal and physical violence to make their workers “productive.”

One of the best “motivators,” in his opinion, is Captain Don Davidson. He is one of the workers at the logging camp and is one of the of the three point of view characters in the novel. The second is Selver, a former Athshean slave who attacked Davison and then was allowed to escape by Captain Raj Lyubov, who is an anthropologist and the third point of view character. Davidson demonstrates the callous attitude towards nature that caused his Earth to become barren. He calls the indigenous population “creechies” and hunts the animals on the planet for sport. He sees himself as “a world-tamer”: (14). He thinks “it’s Man that wins, every time. The Old Conquistador” (15). Selver is not “a world-tamer” but “a world-changer.” He learns violence from the Terrans and teaches the Athsheans how to attack in order to save themselves and their world from the colonizing Terrans: “Selver had brought a new word into the language of his people. He had done a new deed. The word, the deed, murder” (124). Lyubov is the tragic middle man. He understands both cultures and sees each culture’s inability to interpret the other. The Terrans are too greedy and too stubborn to attempt to understand the “humanity” of the Athsheans, while the Athsheans, as the weaker colonized people, quickly decide that they must adopt the violent ways of the humans if they want to keep their world.

This book is the perfect marriage of Le Guin’s interests in anthropology and ecology as well as her penchant for standing up and speaking out. In her introduction to the book, reprinted in The Language of the Night, Le Guin tells us that she wrote the novella in “pursuit of freedom” … but “succumbed, in part, to the lure of the pulpit” (151). She further describes her protests against the Viet Nam War during 1968. This text illustrates her frustration with the war itself but also with the amount of collateral damage the fighting caused to the Vietnamese eco-system and the non-combatants. Her motives were transparent then and have remained so over the years. For example, the book appears beside a bed in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket as a telling anachronism. The irony is: even though the book was partially engendered by one of the most significant events in the late twentieth century and even though Le Guin’s ex post facto introduction almost apologizes for its proselytizing tone, the book still speaks to the world of the twenty first century. In many ways this is unfortunate because this means there are still Don Davidsons in the world.

This book is the perfect marriage of Le Guin’s interests in anthropology and ecology as well as her penchant for standing up and speaking out. In her introduction to the book, reprinted in The Language of the Night, Le Guin tells us that she wrote the novella in “pursuit of freedom” … but “succumbed, in part, to the lure of the pulpit” (151). She further describes her protests against the Viet Nam War during 1968. This text illustrates her frustration with the war itself but also with the amount of collateral damage the fighting caused to the Vietnamese eco-system and the non-combatants. Her motives were transparent then and have remained so over the years. For example, the book appears beside a bed in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket as a telling anachronism. The irony is: even though the book was partially engendered by one of the most significant events in the late twentieth century and even though Le Guin’s ex post facto introduction almost apologizes for its proselytizing tone, the book still speaks to the world of the twenty first century. In many ways this is unfortunate because this means there are still Don Davidsons in the world.

I recommend the book highly. It is a quick read that will make you consider humanity in many of its lovely and gruesome forms. Le Guin gets the last word about this classic: “The work must stand or fall on whatever elements it preserved of the yearning that underlies all specific outrage and protest, whatever tentative outreaching it made, amidst anger and despair, toward justice, or wit, or grace, or liberty” (The Language of the Night 152).

GMRC Review: Powers by Ursula K. Le Guin

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, has gotten his January GMRC review in just under the wire. He’s an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, has gotten his January GMRC review in just under the wire. He’s an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com.

Powers is the third book in The Annals of the Western Shore, a YA series, with Gifts and Voices preceding it, and the only one that can be read as a stand-alone novel (hence my review for the GMRC, although Voices is to me the more accomplished and solid book of the series). However, the ending will be much more meaningful if all three were read in sequence. The books are loosly connected by a couple of characters, Orrec and Gry – we meet them as children in Gifts, and finally as adults in the final chapter of Powers. The seperate stories are set in geographically dispersed areas of the Western Shore and concern characters with different magical abilities, or gifts. The gifts are what make the families of the Uplands different, and even feared as witches by Lowlanders.

Powers is the third book in The Annals of the Western Shore, a YA series, with Gifts and Voices preceding it, and the only one that can be read as a stand-alone novel (hence my review for the GMRC, although Voices is to me the more accomplished and solid book of the series). However, the ending will be much more meaningful if all three were read in sequence. The books are loosly connected by a couple of characters, Orrec and Gry – we meet them as children in Gifts, and finally as adults in the final chapter of Powers. The seperate stories are set in geographically dispersed areas of the Western Shore and concern characters with different magical abilities, or gifts. The gifts are what make the families of the Uplands different, and even feared as witches by Lowlanders.

Le Guin is in familiar territory when telling Gavir’s story. Like the previous books, the narrative is told from the first-person perspective. Gavir is the house slave of a wealthy, cultured and relatively enlightened and benign family in a town called Arcamand. He has two gifts, the ability to see events that have not yet happened, as a "memory," and the ability to remember anything he has read, able to recite the complete story verbatim. One is clearly supernatural, the other, arguably, not. In the end, though, the magical abilities are less important than the social circumstances of the characters. A thread seems to run through the series: a reluctance, perhaps even a fear, to use these gifts. The question is one of power and the consequences of its use and misuse and of choice. Towards the end, when Gavir is tutored by Dorod, this choice becomes brutaly clear: control and use the power and accept the cruelty that it brings, or find another way. Wisely, early in the book, Gavir’s sister convinces him to never reveal his abilities. It is not a spoiler to reveal that Gavir does find another way.

Initially all is well. Gavir is truly happy and content with life, albeit a life badly distorted by the mechanisms of organised slavery. The first section of the book is clearly recounted by a priviliged slave living in far better conditions generally associated with his kind, even to the extent that he may go to school. With subtelty that’s almost cogent, Le Guin unravels the true nature of the oppressive society, showing just how capricious the amity of the household can be, and how utterly dangerous Gavir’s trust in his owners is. As his character develops, Gavir gradually comes to understand and accept even the betrayal of his trust. At this point Le Guin demonstrates yet again the range and depth of her artistry as Gavir informs us:

"It grieves me that blind hate and rancour should be my last link to Arcamand. I could think now of the people of that house with gratitude for what they had given me – kindness, security, learning, love. I could never think that Sotour or Yaven has or would have betrayed my love. I was able to see, in part at least, why the Mother and the Father had betrayed my trust. The master lives in the same trap as the slave, and may find it even harder to see beyond it. But Torm and his slave-double Hoby never wanted to look beyond it; they valued nothing but power, the most brutal control over people. My escape, if he heard of it, would have rankled Torm bitterly. As for Hoby, always seething with envious hatred, the knowledge that I was going about as a free man would goad him to rageful, vengeful persuit" (page 355, Orion edition 2008).

Where Gavir once may have believed that a social order of master and slave is the natural way of things, he slowly begins to percieve the true injustice of it, and when a horrible tragedy strikes, his life begins to rapidly change. Almost by accident Gavir escapes his slavery, and the narrative transforms into a compelling and riveting journey with equally compelling characters. When Gavir takes to the road, heading back to his people, it’s the beginning of his coming of age journey. He must try to understand the nature of his own talents, but always his past as a slave haunts him, like a shadow. Hoby, who once bullied him before he made his escape, ultimately after many years’ searching, tracks him down. The river crossing explained in a few short paragraphs remains for me one of the most touching and unforgettable narratives in all of Le Guin’s work, a symbolic crossing perhaps every child is destined to make.

"The way to go was plain at first, the clear water showing me the shallows between the shoals. Out of the middle of the water, I looked back once. The horseman had seen us. He was just riding into the river, the water splashing up about his horse’s legs. It was Hoby. I saw his face, round, hard, and heavy, Torm’s face, the Father’s, the face of the slave owner and the slave…. I saw it all in a glance and waded on, crosscurrent, pulling the child with me as best I could…. I knew where I was then. I had been in this river with this burden on my shoulders. I did not look around because I do not look around, I go forward, almost out of my depth, but still touching bottom, and there is the place that looks like the right way to go…." (pages 369-370, Orion edition 2008).

Le Guin’s metaphors and imagery and insights are no less powerful, no less beautiful. She can still create myths.

Le Guin’s metaphors and imagery and insights are no less powerful, no less beautiful. She can still create myths.

The final two chapters of Powers are just overwhelmingly moving, simply spectacular, and the reason why this series is now one of my favourites, alongside Earthsea. Gavir becomes a character to really like, endearing and respected, not only because of his love for scholarship and reading, but because of Le Guin’s remarkable and canny ability to remember and depict the crises and concerns of adolescence that could easily have been my story. Attentive readers will meet themselves and, sadly, the worst of the societies we live in.

Powers still resonates with me, long after I finished it. Le Guin’s familiar subjects and motifs are still present, as the all-encompassing political concern for the protection and the nurture of human freedom in all aspects of human life, and the urgent need for the creation of a real human community. This is a message I don’t mind young adults hearing. There is no miraculous conversion of slave owners, renouncing their evil, oppressive ways. Like life, there are no easy answers, but in the end, hanging on, things do get better. I, for one, do believe that.

Highly recommended, not only for young adults.

Outside the Norm: Ursula K. Le Guin’s Rocannon’s World and City of Illusions

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

When Rocannon’s World, Planet of Exile and City of Illusions were reprinted in the mid-1970s, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote introductions for each novel. Those introductions contain two passages that tell you everything that you need to know about Rocannon’s World and City of Illusions:

When Rocannon’s World, Planet of Exile and City of Illusions were reprinted in the mid-1970s, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote introductions for each novel. Those introductions contain two passages that tell you everything that you need to know about Rocannon’s World and City of Illusions:

Most of my stories are excuses for a journey. (We shall henceforth respectfully refer to this as the Quest Theme.) I never did care much about plots, all I want is to go from A to B—or, more often, from A to A—by the most difficult and circuitous route. (“Introduction to City of Illusions” in The Language of the Night 147)

And:

But of course fantasy and science fiction are different, just as red and blue are different; they have different frequencies; if you mix them (on paper—I work on paper) you get purple, something else again. Rocannon’s World is definitely purple. (“Introduction to Rocannon’s World” in The Language of the Night 133)

Both novels are about planetary outsiders who must go on a quest. Rocannon, the ethnologist studying Fomalhaut II, is the sole survivor of his expedition group. An unknown alien race blows up his ship and his companions. The destruction of the ship eliminates his mode of communication; therefore, he can’t tell his people that the planet has been attacked. He has no way to protect the indigenous people. Traveling south to the base of the enemy to use their communication equipment to contact his people is his only option. Rocannon assembles a Tolkiensque group, and they begin their quest. The beats of their journey closely resemble Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, outlined in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. There are helpers, threshold guardians, tests, and even a bit of apotheosis. (Another good website about the monomyth is here.)

Falk’s journey in City of Illusions is a quest to learn who he is. The novel opens with Falk’s discovery by an agrarian society. He has no memory, no language. They foster him and teach him their ways, but he is not of their species. He has amber, cat-like eyes that mark him as alien. After living with these people for five years, his instinct tells him that he must journey west toward the legendary city of Es Toch to learn who he is. Unlike Rocannon, he usually travels alone, but like Rocannon, he encounters tests, helpers and threshold guardians along the way.

I enjoyed the “purpleness” of both novels as they placed the quest myth on unknown, or at least immediately unrecognizable, planets, whose cultures would be at home in high fantasy. In Rocannon’s World, Le Guin enlivens Norse myth with a slice of Tolkien. The Liuar species who travel with Rocannon has two classes: the Olgyior, who are the servants, and the Angyar, who are the lords. They live within a “feudal-heroic culture,” which Le Guin sums up this way: “They were a boastful race, the Angyar: vengeful, overweening, obstinate, illiterate, and lacking any first-person forms for the verb ‘to be unable.’ There were no gods in their legends, only heroes” (4, 37).

I enjoyed the “purpleness” of both novels as they placed the quest myth on unknown, or at least immediately unrecognizable, planets, whose cultures would be at home in high fantasy. In Rocannon’s World, Le Guin enlivens Norse myth with a slice of Tolkien. The Liuar species who travel with Rocannon has two classes: the Olgyior, who are the servants, and the Angyar, who are the lords. They live within a “feudal-heroic culture,” which Le Guin sums up this way: “They were a boastful race, the Angyar: vengeful, overweening, obstinate, illiterate, and lacking any first-person forms for the verb ‘to be unable.’ There were no gods in their legends, only heroes” (4, 37).

Also, on the planet are the Gdemiar, who had a dwarfish culture before the Hainish envoys enhanced their culture to an industrial level, and the Fiia, who live an elvish, agrarian lifestyle. The Fian, Kyo, who has lost his whole village, joins the quest, giving the reader an insight into that culture that we don’t with the Gdemiar.

In City of Illusions Falk’s journey across a post-apocalyptic North American continent exposes him to many cultures we would see in fantasy novels. There are extended-family agrarians, hunter-gatherers, Taoist hermits, and isolationists, all of whom have developed rituals that suit their cultural needs. The isolationists are the Bee-Keepers, “[a] strange lot, literate and laser armed, all clothed alike, men and women, in long shifts of yellow wintercloth marked with a brown cross on the breast” (277).  While they treat Falk well, he learns that they capture outside women solely to breed more Bee-Keepers and “worship something called the Dead God, and placate him with sacrifice—murder” (278). Each group Falk encounters serves as either helpers or hinderers on his journey, just as they should in a good quest myth.

While they treat Falk well, he learns that they capture outside women solely to breed more Bee-Keepers and “worship something called the Dead God, and placate him with sacrifice—murder” (278). Each group Falk encounters serves as either helpers or hinderers on his journey, just as they should in a good quest myth.

The characters and ideas expressed in City of Illusions are much more complex than those in Rocannon’s World. Le Guin’s Taoism is much more pronounced as she queries the difference between truth and lies throughout Falk’s journey. The characters and situations are much more gray than the starker black and white of Rocannon’s World. However, I enjoyed reading Rocannon’s World much more. I liked Rocannon more than Falk, perhaps because Falk is a mystery through most of the book. Both books give us a glimpse of the writer that Le Guin will become. We see her world-building, her fascinating cultures, and her wonderful prose.

GMRC Review: The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and has chimed in with his first GMRC review of one of the all time classics of SF.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and has chimed in with his first GMRC review of one of the all time classics of SF.

The Dispossessed is the fourth book in Ursula K. Le Guin‘s Hainish Cycle, which is a loosely connected series of books, novellas, and short stories utilizing the background of an inter-stellar proto-humanity that seeks to reunite it’s disparate colonies. Although it is the fifth work in the series, chronologically it is the first. Le Guin pulled at hat trick with this one and nabbed the 1974 Nebula and the 1975 Hugo and Locus awards. My only other experience with Le Guin was reading The Left Hand of Darkness (another book in the Hainish cycle) as part of a capstone fiction class for my Bachelor’s degree. We really dug into the book, and one element we looked at particularly closely is the cyclical plot structure in which the protagonist, Genly Ai, ends up where he started, though greatly changed by the experience. Thinking about that reading experience reminded me of what a visiting author said in a lecture that same year: there are two types of stories, someone goes on a trip or a stranger comes to town. Sometimes, though, that stranger is you returning. Indeed, illustrating that appears to be the point of The Dispossessed‘s structure and themes: to take us on a trip to a world similar to ours, but through different eyes so that the familiar becomes strange and we, upon returning from the journey, are changed by the experience. Le Guin has characterized herself and has been characterized as an anthropologist of cultures that never existed, but might in the future, and The Disposessed is a prime example that puts paid to this claim. The science in this book is very soft, but like The Left Hand of Darkness, it delves deep into social structures and hierarchies that characters within her fictional societies have built and struggle within.

The Dispossessed is the fourth book in Ursula K. Le Guin‘s Hainish Cycle, which is a loosely connected series of books, novellas, and short stories utilizing the background of an inter-stellar proto-humanity that seeks to reunite it’s disparate colonies. Although it is the fifth work in the series, chronologically it is the first. Le Guin pulled at hat trick with this one and nabbed the 1974 Nebula and the 1975 Hugo and Locus awards. My only other experience with Le Guin was reading The Left Hand of Darkness (another book in the Hainish cycle) as part of a capstone fiction class for my Bachelor’s degree. We really dug into the book, and one element we looked at particularly closely is the cyclical plot structure in which the protagonist, Genly Ai, ends up where he started, though greatly changed by the experience. Thinking about that reading experience reminded me of what a visiting author said in a lecture that same year: there are two types of stories, someone goes on a trip or a stranger comes to town. Sometimes, though, that stranger is you returning. Indeed, illustrating that appears to be the point of The Dispossessed‘s structure and themes: to take us on a trip to a world similar to ours, but through different eyes so that the familiar becomes strange and we, upon returning from the journey, are changed by the experience. Le Guin has characterized herself and has been characterized as an anthropologist of cultures that never existed, but might in the future, and The Disposessed is a prime example that puts paid to this claim. The science in this book is very soft, but like The Left Hand of Darkness, it delves deep into social structures and hierarchies that characters within her fictional societies have built and struggle within.

The Dispossessed takes place on the planets of Urres and Anarres, which orbit one another in the Tau Ceti star system. Anarres is a desert planet colonized by anarchists who split with Urres. The Anarresti anarchy eschews money, property, and materialism in general, favoring an extremely decentralized government in which an individual is free to do what he/she wants, but is always expected to contribute to the communal whole. Annarresti’s share in both the drudge work like planting crops and waste management as well as the higher-order tasks such as management and even research. Everyone pitches in, and being selfish or "egoizing" is frowned upon. This makes Shevek, our protagonist, somewhat of an outlier. Shevek struggles with being a member of the community and with trying to fulfill his dream of creating a unified theory of space and time. It is his ideas that will make the interstellar communicator, the ansible (an important device in the other parts of the Hainish cycle) possible. But the work isolates him, since few understand it or even want to. He eventually seeks intellectual community with the scientists on Urres, which the Anarrans regard as wicked, materialistic heathens. Shevek risks becoming anathema to his people not only because his theory could reveal the way to bring the communities of star-flung humanity together, but also a way to lower the barriers separating Urres and Anarres. Of course, everyone on Urres wants to be the ones to get their hands on Shevek’s work, and he slowly comes to realize the peril this puts him in. Through Shevek’s anarchist eyes, we see how the people of Urres–particularly the caplitalist, materialist A-Io and the communist nation of Thu (mirroring the United States and Soviet Russia respectively)–are strange and sometimes horrifying, but not irredemable.

What The Dispossessed Does Well

The science in this book is very soft. Indeed, it is pretty much downplayed throughout. Even Shevek’s theories of space-time are not expounded upon beyond some simple analogies. This is pure social science fiction, and it is perhaps best approached with an anthropologist’s eye for social dynamics. Shevek comes from a world where one is brought up from childhood to see everyone as a brother or sister (even one’s biological parents), to treat everyone equally, and to eschew the idea of personal property, and to contribute to one’s society. One of the strengths of this book is in Le Guin’s speculation on how a utopian society of anarchists might function to achieve these goals (anarchy here does not connote an absence of morality or order, but rather a society without institutionalized hierarchies of power and control). Crime is negated by eradicating money and making all property communal and free, therefore there is no need to steal or murder someone for what he/she has. People work as they want to, and given the strong social nature of this society, most people pitch in in some way to contribute. This leads to a large portion of unspecialized labor, but it encourages people to work for what pleases them and what motivates them instead of being chained to the same job. Le Guin incorporates a somewhat strong version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis as a tool for reinforcing the anarchic ideals of Anarres. You do not refer to something as "my book" on Annares, but say "the book". You don’t ask, "can I see your book," you say, "can I use the book that you are using"? It gets weird some times when characters say "the mother" instead of "your mother," or "the nose hurts" instead of "my nose hurts," but it’s all geared towards eliminating possessiveness: if the use of language affects cognition and non-linguistic actions, then eliminating possessiveness in speech eliminates it in thought and action, according to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

The plot structure also mirrors this duality: the chapters alternate between Shevek’s time on Urres and his earlier life on Anarres, with situations and themes from these alternating chapters mirroring each other. Just as the two planets orbit one another, Le Guin creates a constant juxtaposition of the two worlds throughout the book. We will see the material excesses, the squalor of the poor, and the "savage civility" (a term I loved from John Masters’ description of the upperclasses in Nightrunners of Bengal) of the Urresti capitalists in one chapter, and how the solidarity of the Anarrans was strenghtened by the way they pull together during a food shortage in the next. Since the social-political situation on Urres is close to that of the Cold-War era Untied States and Soviet Union, Shevek provides a contrasting viewpoint that let’s Le Guin level some pretty incisive criticism about the inequality of men and women, material excess, the petty (and dangerous) nationalism, the governmental and corporate co-opting of science, etc.

The contrast between the two worlds and the way these differences are presented in the alternating plot structure makes Anarres seem a tempting utopia, but thankfully Le Guin complicates the issue. The book is subtitled "An Ambiguous Utopia," after all, and Anarres is not perfect. In the generations following the revolution, informal power hierarchies establish themselves, sometimes explicitly–as in the case of the inept yet famous scientist Sabul whom Shevek has to appease to get his theories published–and tacitly, as in peer pressure. This ambiguity is further reinforced by the beauty on Urres, such as the technological wonders of aircraft and spaceships and the general material abundance, which is made possible by the plentiful resources of the planet. Shevek wrestles with these differeneces and moves towards a realization of how he can help revitalize the revolution on his planet, and thus he ends where he began and completes the loop mirrored in his theory of simultaneity and the oft quoted dictum by Anarres’ intellectual founder that "true journey is return." All of this is presented pretty well through conversations (the tenor of which makes me think of Kim Stanley Robinson sans the hard science) and through Shevek’s observations, tinged by his upbringing in a very different society than that of Urres, which leads to scenes that are sometimes hilarious, sometimes disquieting, but always thought provoking. The complications Le Guin adds to the Annaresti anarchy and the startling beauty Shevek occasionally notices on Urres keeps the plot of the themes from being cliche or simplistic.

The contrast between the two worlds and the way these differences are presented in the alternating plot structure makes Anarres seem a tempting utopia, but thankfully Le Guin complicates the issue. The book is subtitled "An Ambiguous Utopia," after all, and Anarres is not perfect. In the generations following the revolution, informal power hierarchies establish themselves, sometimes explicitly–as in the case of the inept yet famous scientist Sabul whom Shevek has to appease to get his theories published–and tacitly, as in peer pressure. This ambiguity is further reinforced by the beauty on Urres, such as the technological wonders of aircraft and spaceships and the general material abundance, which is made possible by the plentiful resources of the planet. Shevek wrestles with these differeneces and moves towards a realization of how he can help revitalize the revolution on his planet, and thus he ends where he began and completes the loop mirrored in his theory of simultaneity and the oft quoted dictum by Anarres’ intellectual founder that "true journey is return." All of this is presented pretty well through conversations (the tenor of which makes me think of Kim Stanley Robinson sans the hard science) and through Shevek’s observations, tinged by his upbringing in a very different society than that of Urres, which leads to scenes that are sometimes hilarious, sometimes disquieting, but always thought provoking. The complications Le Guin adds to the Annaresti anarchy and the startling beauty Shevek occasionally notices on Urres keeps the plot of the themes from being cliche or simplistic.

Where The Disposessed Could Have Been Better

Even though this is a work of social science fiction, sometimes the narrative can feel disembodied as it summarizes situations or stretches of time in Shevek’s life. These scenes do reveal a great deal about Annaresti society, but such exposition can distract from Shevek’s narrative. When Le Guin does delve into an extended scene there is some great characterization done in the dialog, but the lengthy exposition lies between these scenes and bobbing in and out of it left me feeling light headed at times. The alternating chapters also made me feel dizzy as the narrative shifted gears, and for some reason I was frequently drawn in to the scene at the end of a chapter only to be extremely disoriented when the narrative shifted to the other planet and the other time period. Perhaps this disorientation is intended, but it still bothered me during those transitions. This is also a book that is curiously without much visual or technological sensawunda. My memories of The Left Hand of Darkness are punctuated by that pervasive awareness of how cold the planet of Gethen was, and of the strangeness of the neuter people there. More visual or technological play in the book would have added welcome nice spice to the narrative.

Concluding Thoughts

The Disposessed is a great book if you know how to approach it. It is social science fiction, so there is not much in the way of action. It is best to approach this book with an anthropologist’s eye, paying attention more to the speculation on social dynamics than to the technological advancements. Still, it’s very thoughtful and incisive, and it illustrates an important facet of SF that readers outside of the genre probably don’t think it can do very well: deep social critique. Although it was written thirty seven years ago, it still feels fresh and interesting. It’s an important piece of SF, and a nice companion to The Left Hand of Darkness.

Score: 5/5

Full Details

Full Details