Fire or Ice?

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great,

And would suffice.

– Robert Frost

As you may or may not know by now, today is the last day…. ever. At least, that’s what Harold Camping and the Family Radio network have been preaching since the last armaggedon failed to appear in 1994. Since this may be our final blog post on this earth, we thought it might be a good time to remember other predictions of our impending doom. Perhaps we can finally settle the question posed by the good Robert Frost a mere 88 years ago. Will the world end in fire or ice?

First up: Walter Miller. His Hugo winning novel A Canticle for Leibowitz is a personal favorite of mine (as you can tell from my avatar). In it, the world undergoes a nuclear holocaust, plunging humanity back into the dark ages where the only shreds of written knowledge are preserved by ascetic monks in the southwestern deserts of North America.  This classic features not one but two armageddons, illustrating the futility of technological conflict. He wrote the book as a sort of penance for his involvement in the destruction of Montecassino during World War II. The event left such a scar on his psyche that only beating out this masterpiece could quell it. Miller’s vote: FIRE.

This classic features not one but two armageddons, illustrating the futility of technological conflict. He wrote the book as a sort of penance for his involvement in the destruction of Montecassino during World War II. The event left such a scar on his psyche that only beating out this masterpiece could quell it. Miller’s vote: FIRE.

Jack Vance invented the “Dying Earth” sub-genre with his novel, The Dying Earth. Unrecognized in his time, the trendsetting novel has been named one of The Classics of Science Fiction and is included in the Fantasy Masterworks list by the Orion Publishing Group. This Earth of the distant future revolves around a red giant that is inexorably dying out. Like the sun, the human race is also a dim reflection of its former self, relying on the remnants of forgotten technology and magic.  Vance was known for the mixing of science fiction and fantasy, and the trope of a massive but cooling sun dominating a now red sky provides a fantastic backdrop for both genres. Though the planet is not quite destroyed in this 1960’s series, its inevitable fate is known. Jack Vance votes ICE. (P.S.: I’ve always wondered whether Jack Vance was the inspiration for Vance Refrigeration in The Office.)

Vance was known for the mixing of science fiction and fantasy, and the trope of a massive but cooling sun dominating a now red sky provides a fantastic backdrop for both genres. Though the planet is not quite destroyed in this 1960’s series, its inevitable fate is known. Jack Vance votes ICE. (P.S.: I’ve always wondered whether Jack Vance was the inspiration for Vance Refrigeration in The Office.)

Rarely do we get to see the Earth actually die in a science fiction novel. Sure, it might sustain a few nuclear wars or a couple of extinction events, but it’s hard to continue a story when all of your characters are dead. You can imagine my delight, then, when I re-read H.G. Wells‘ The Time Machine. Sure, everyone rememebers the Morlocks and the Eloi. You might still have a few whispy dreams of the lovely Weena, the Time Travellers demure girlfriend from the year 802,701 A.D. What I forgot, however, was the protagonists final trip to the ends of the Earth (literally). For those who are a little foggy on the details, we’ll fill you in. After rescuing his shorty, the Time Traveller travels another 30 million years into the future, where he witnesses crabs and butterflies sparsely inhabiting blood-red world of simple vegetation. A few jumps later gives us the answer we seek: the Earth’s rotation stops and the sun shrinks away until the earth and everything in it sets in for a deep freeze. For Mr. Wells, that’s a definite ICE.

A few other WWEnd author votes include:

Gene Wolfe votes ICE with his classic series, The Book of the New Sun, which describes an “Urth” in a distant future whose sun is dying.

The great Larry Niven begs FIRE in a big way with Lucifer’s Hammer, where the planet gets smacked with a (near) extinction event in the form of an asteroid.

If you want a definitive answer to the way the world ends, you can’t get any closer than This is the way the World Ends, by James Morrow. He nabbed nominations for both the Nebula and Campbell awards, casting his vote for FIRE by way of a nuclear war.

This leaves us with a tie of 3-3, but what do I know? I just picked six books at random. Please add to the list by citing your favorite WWEnd authors, or even authors not yet in our database. Hell, cast your own vote. We just need to break this tie. Please hurry, though. We only have until 6PM before the latest scheduled apocalypse.

Reviewing Miller, Part 5: “But now to nourish death.”

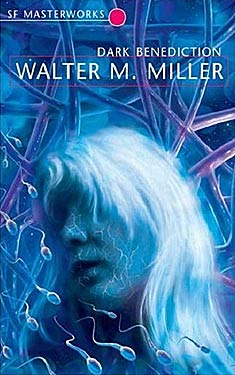

This series reviews the short stories found in Walter Miller’s Dark Benediction collection. This is the final installment. (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4)

This series reviews the short stories found in Walter Miller’s Dark Benediction collection. This is the final installment. (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4)

The Darfsteller

Also known as Walter Miller’s other Hugo-winning story, "The Darfsteller" presents an episode late in the life of aging theatrical actor Ryan Thornier. Years ago human actors have been bullied off the stage by mechanic automotons called dolls which have been imprinted with the personality patterns of popular actors who have signed their careers away to the Smithfield corporation. Those actors popular enough got a Smithfield contract, and the rest got a stolen dream, but none of them got to stay on stage. Thornier has never given up on artistic integrity, even though he had to make a living as a janitor in one of the robotic theatres, but while he "had stood firm on principle… the years had melted the cold glacier of reality from under the principle." This story is an account of his last attempt to save himself.

Dark Benediction

Much like "Dumb Waiter," this story takes place in a future that is, if not exactly post-apocalyptic, at least a pessimistic take on the human race. Meteors have fallen to earth which contained a parasitical infection that has already spread to one-third of the human race, causing the structures of civilization to collapse. The infected are known as "dermies" because the infection is spread by physical touch of hand-on-skin, and because the infected possess an almost irresistable urge to touch the uninfected. The dermies’ skin turns grey, and they are said to experience hallucinations that some think are tied to a restructured nervous system. It’s unclear to many if the dermie infection is even harmful, but mass panic has caused all social systems to collapse and has driven the world into a state of perpetual fear. The "benediction" of the title is a play on the religious practice of the laying on of hands to give a blessing, and indicates the belief of the dermies that they are giving a gift to those they infect. (Incidentally, the sperm-like creatures on the book cover above is a representation of the alien parasite from this story.)

The Lineman

Set on the moon in the late twenty-first century, "The Lineman" is a brief look at the harsh life endured by lunar workers in the early stages of extraterrestrial colonization. The twist that gets the story moving—the arrival of a space-bound brothel—reminded me of the old C.S. Lewis story "Ministering Angels," but without the wry sense of humor Lewis brought to the subject. This is one of Miller’s weaker stories from this collection, and it never really comes together coherently to make a point.

Vengeance for Nikolai

This story, on the other hand, is a short but frightfully vivid nightmare of a near-future war between an America that has been overtaken by a nationalist party and the Soviets (this was written in 1956, mind you). A woman, Marya Dmitriyevna, has recently lost her infant son Nikolai in an attack, and is given the chance to revenge herself upon the Americans by a Russian colonel. The American military has a general, Rufus MacAmsward, who may be half-mad, but whose strategies have thus far managed to overcome any obstacle. He also has a thing for women. I won’t ruin the ending, but it is dark and funny and disturbing all at once.

In Closing

All things considered, this is a pretty solid collection of science fiction stories. It shows off Miller’s talent as well as his versatility. I suspect he could have written a dozen novels, and each one would have been both brilliant and entirely different than any of the others. It’s a pity his output mostly stopped with A Canticle for Leibowitz, especially after seeing the potential only hinted at in this collection.

Next up for review, Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman?

Reviewing Miller, Part 4: “Where is his peace?”

This series reviews the short stories found in Walter Miller’s Dark Benediction collection. (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

This series reviews the short stories found in Walter Miller’s Dark Benediction collection. (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

Blood Bank

Commander Eli Roki shoots down an emergency supply ship from Earth in what is apparently cold blood, but why? He has suspicions about the cargo the ship was holding, but has no proof of any wrongdoing. He is stripped of his rank and sets out to prove himself right… or die trying. In “Blood Bank” Miller creates a galaxy of planets which individually hold various evolutionary lines of the human race, each having adapted in some way to its environment. While Miller overestimates the speed at which the Darwinian theory of natural selection allows for such change, it does make for some fascinating speculation. There is also in this story a brief touch upon Miller’s favorite theme of abandoning or limiting the use of technology.

Big Joe and the Nth Generation

It is Mars in the far future, and the artificial atmosphere humans generated eons ago is slowly leaking out into space. Add to this problem the fact that Martian inhabitants have regressed into a primitive society which only has legends about the trees and the air being planted from the heavens by the Ancient Fathers, and you’re in a lot of trouble. Asir is an idea thief who has spent his life collecting—society calls it stealing—fragments of ancient wisdom which have been passed down through oral tradition, and having put these fragments together he realizes that the world will end soon if he doesn’t do something about it.

The Big Hunger

This is Miller’s poetic ode to space travel. Told from the perspective of some enigmatic and abstract observer, mankind reaches out to the stars over and over again. He leaves Earth and finds a habitable planet; he settles down, gets comfortable, builds a new civilization; he gets tired of the comfort, yearns for the stars, and leaves, beginning the cycle anew. Over and over he spreads himself across the galaxy, looking for something, maybe some kind of paradise from which he was banished. Many planets eventually lay claim to the name of Earth, to being the place of origin, but will the restless race find happiness even if it can find its roots?

Conditionally Human

Inspector Norris is in charge of a pound, and his new wife is very unhappy to find out about this. In the near future, population growth has led to draconian limits on procreation, and subsequently to the creation of mutated animals that have just enough intelligence to fill the emotional void of the child that is not there. Dogs can talk gibberish and chimps have been altered to look almost human, and have their physical development arrested at the level of a toddler. Mommy’s little baby. Norris catches strays and unwanted “children,” and quietly disposes of them as needed. It is a cold, frightening look at the things we are willing to do to keep ourselves comfortable at any cost.

Next time we close out this collection with “The Darfsteller,” “Dark Benediction,” “The Lineman” and “Vengeance for Nikolai”

Reviewing Miller, Part 3: “Pain Button”

This series reviews the short stories found in Walter Miller’s Dark Benediction collection. (Part 1, Part 2)

This series reviews the short stories found in Walter Miller’s Dark Benediction collection. (Part 1, Part 2)

I, Dreamer

It’s a setup disturbing enough to be from the mind of Harlan Ellison: infants are stolen from mothers and their brains are used to operate sophisticated war machines for the conquest of Earth. Bouncing between free indirect style and first person point-of-view, Miller tries to show the inner consciousness of a being who thinks it is an artificial intelligence but is really human. It is a life of anxiety, desire and frustration, as the being known as Clicker is tortured by his “TwoLegs” handler at the merest sign of insubordination. The story is at the same time horrific and touching, as the maybe-reunion at the end is consummated in an act of irreversible destruction.

Dumb Waiter

This is a longer story that feels in some ways like a rough draft for A Canticle for Leibowitz, in theme if not in plot. There has been a war that was fought mostly by means of an artificial intelligence built to run a city and all its mechanized systems. The local city was made uninhabitable not only by the radioactive dusting attack but by “Central,” the city’s learning system that still keeps police, traffic and energy bills running in perpetuity long after the war is over. Jaywalkers or anyone breaking long-forgotten laws are arrested by self-propelled robotic policemen and tossed in jails with crumbling infrastructures, and handed foodless trays every day until they starve to death. Even rusting bomber planes are sent out every day on missions to drop bombs they no longer possess. The rural population that survived is intent on destroying the machines once and for all, ridding themselves of all technology, but a strange man named Mitch who is inexplicably heading into the city has other plans. While this story isn’t as deep as Canticle, it’s fascinating to see what amounts to an early draft of Miller’s ideas for the novel.

Next time: “Blood Bank”

Reviewing Miller, Part 2: “Quiet Misery”

Continuing our series from two weeks ago (apologies for the week-long gap), we will now proceed with the third and fourth short stories in Walter M. Miller’s Dark Benediction series, “Anybody Else Like Me?” and “Crucifixus Etiam,” two very different stories.

Continuing our series from two weeks ago (apologies for the week-long gap), we will now proceed with the third and fourth short stories in Walter M. Miller’s Dark Benediction series, “Anybody Else Like Me?” and “Crucifixus Etiam,” two very different stories.

Anybody Else Like Me?

This story has the feel and narrative structure, oddly enough, of an H. P. Lovecraft short horror story. Thankfully, Miller does not copy the New Englander’s penchant for purpling his prose, and sticks with his workmanlike vocabulary. The protagonist of this short and chilling tale is Lisa Waverly, a wife and mother who is “well-read, well-rounded, well-informed…. Then why this quiet misery?” (30). Miller makes you briefly think that he is going to give you an early-feminist story of self-created female angst and misery like Virginia Woolf’s or Sylvia Plath’s, only to pull out the rug and expose the terrifying reality that is causing Lisa’s mental anguish. She is a mutant and a telepath and feels emptiness in the absence of others like her. Unfortunately, when she finally does meet another of her kind, he turns out to be a frightening scientist who decides they need to be together at any cost. From the early unraveling of Lisa’s mind, to the growing terror of the danger imposing upon her, to the final confrontation between the two mutants, Miller has a firm grasp on the reader’s adrenaline level through the whole ride.

Crucifixus Etiam

Unlike the previous three stories, this one begins far away from the mundane world we know, in the far future of 2134 A.D. and the distant locale of Mars. The protagonist is Manue Nanti, a Peruvian worker who has been sent to Mars as a manual laborer for a mysterious project. Martian residents have the help of implanted oxygen tubes to help them survive in the thin and alien atmosphere. The life-giving oxygen is pumped directly into their blood such that they do not even need to breath, which leads to such a severe weakening of the lungs that those who return to Earth in that condition cannot live without lifelong medical assistance. Manue does not want to become a “troffie,” one of those whose lungs are so atrophied they can barely even speak, but the pain of forcing himself to breath the wispy air slowly takes its toll, as does his ignorance of the work he is doing. Why do the engineers and corporate heads hide their goals from the common workers? “There could be no excuse for secrecy, they felt, in time of peace. There was a certain arbitrariness about it, a hint that the Commission thought of its employees as children, or enemies, or servants” (60). He likewise feels distanced from the practice of his native religion when he attends Mass, which seems out of place “under the dark sky of Mars…. Faith needed familiar surroundings, the props of culture” (56-7). The resolution of both of these realities of alienation comes about by way of a movement hinted at in the story’s title, taken from the Nicene Creed. It is a sad ending, but one appropriate to the themes of the story.

Next week: “I, Dreamer” and “Dumb Waiter.”

Reviewing Miller, Part 1

Walter Miller’s fiction has long been a favorite of mine. A Canticle for Leibowitz is not just one of my favorite science fiction novels, but one of my favorite novels altogether. There’s something peculiarly epic about that story, and I don’t mean that in the cheap way the word “epic” is generally used these days. I mean it in the way that scholars use it, as a way of describing a story that is universal in scope and powerfully vivid in detail. Leibowitz follows the historical development of mankind after a near-future nuclear inferno, during which we relive the great sweep of civilization from the Roman collapse to the modern, technological age. Miller gives us monks and politicians and radiation-born freaks who remember enough of the past—of our past—that they fear repeating it even as they fatalistically drive towards it. Like I said, it’s one of my favorite books, and it was not a small disappointment to hear that its sequel, Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman, was very poorly made and published by way of some major contributions from another author after Miller had committed suicide with only a partial manuscript in hand. You can imagine my glee upon discovering that a collection of his earlier short stories have been published.

Walter Miller’s fiction has long been a favorite of mine. A Canticle for Leibowitz is not just one of my favorite science fiction novels, but one of my favorite novels altogether. There’s something peculiarly epic about that story, and I don’t mean that in the cheap way the word “epic” is generally used these days. I mean it in the way that scholars use it, as a way of describing a story that is universal in scope and powerfully vivid in detail. Leibowitz follows the historical development of mankind after a near-future nuclear inferno, during which we relive the great sweep of civilization from the Roman collapse to the modern, technological age. Miller gives us monks and politicians and radiation-born freaks who remember enough of the past—of our past—that they fear repeating it even as they fatalistically drive towards it. Like I said, it’s one of my favorite books, and it was not a small disappointment to hear that its sequel, Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman, was very poorly made and published by way of some major contributions from another author after Miller had committed suicide with only a partial manuscript in hand. You can imagine my glee upon discovering that a collection of his earlier short stories have been published.

This collection, entitled Dark Benediction (originally The Best of Walter Miller Jr), has been recently republished by the Orion Publishing Group as a part of the SF Masterworks series. The very trippy cover art can be seen to the left. I purchased it a few weeks ago, and have been slowly making my way through the stories, and I decided that reviewing them one by one would make a great blog series. The first few stories in the collection are quite short, and as such I will combine these together into groups of two. The first two stories in the collection are “You Triflin’ Skunk!” and “The Will.”

Both of these stories share a common sort of setup and development, in both senses of the word “common.” They are set in poor, rural places, and feature largely uneducated people as protagonists. Miller instills in the reader a sense of the mundanity of these people and their surroundings, of their ignorance and simpleness. These people are not great, learned, or even adventurous, but they are all about to experience a collision with the uncanny.

You Triflin’ Skunk!

“You Triflin’ Skunk!” is exceptional firstly for its unusual title, which would seem to suit a Flannery O’Connor story better than one of alien visitation. Indeed, the rural isolation of the religious protagonist Lucey seems like the perfect setup for one of O’Connor’s morality tales, and it helps that Miller takes his time developing the ordinariness of the situation, only revealing the back story of Lucey and her epileptic boy Doodie one piece at a time. Doodie, you see, hears voices during his fits, and he claims he actually hears the voice of his father, who can speak to him telepathically through the tumor-like growth in his forehead. The boy claims to be one of many half-breeds, the son of a priapic alien and a human mother, whose purpose is to prepare the earth for invasion. Lucey mocks this revelation, but that doesn’t stop her from carrying a shotgun with her outside on the night her son warns of his father’s coming.

The Will

This is the sad story of a boy, Kenny, who is diagnosed with an unspecified terminal disease. He loves watching the televised exploits of Captain Chronos, “Custodian of Time, Defender of the Temporal Passes, Champion of the Temporal Guard,” so when he finds out about his disease he hatches a plan to save himself. I won’t ruin it for you, but it isn’t that hard to figure out. As with the first story, “The Will” builds up the mundane world of Kenny and his parents before Miller sets to ripping the rug out from beneath your feet. One of the things Miller does so well is to make you care about these characters before he starts to bother you with fantastic elements of science fiction. His characters are never mere plot devices, but real people who matter very much. These aren’t exactly morality plays—and Leibowitz definitely had a moral character—but the stories are at least about people rather than ideas.

Tune in next week when I review “Anybody Else Like Me?” and “Crucifixus Etiam.”

Full Details

Full Details