2018 Mythopoeic Award Finalists

The Mythopoeic Society has announced the finalists for the 2018 Mythopoeic Award. For Adult Literature they are:

- Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruin of Ymr by John Crowley (Saga Press, 2017)

- The Rules of Magic by Alice Hoffman (Simon and Schuster, 2017)

- Snow City by G.A. Kathryns (Sycamore Sky Books, 2017)

- Passing Strange by Ellen Klages (Tor.com, 2017)

- The Changeling by Victor LaValle (Spiegel and Grau, 2017)

Our congrats to all the finalists. See the official press release for details on the other categories. The winners of this year’s awards will be announced during Mythcon 49, to be held July 20-23, 2018, in Atlanta, Georgia.

2018 Andre Norton Award Winner!

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America have announced the winner of the 2018 Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy:

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America have announced the winner of the 2018 Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy:

The Art of Starving by Sam J. Miller (HarperTeen)

The award was announced with the Nebula winners over the weekend.

Our congrats to Sam J. Miller and all the nominees:

- Exo by Fonda Lee (Scholastic Press)

- Weave a Circle Round by Kari Maaren (Tor)

- Want by Cindy Pon (Simon Pulse)

What do you think of this result?

2017 Nebula Award Winner!

The 2017 Nebula Awards were presented at a ceremony held in the Pittsburgh Marriott City Center in Pennsylvania on the evening of May 19, 2018. The best novel winner is:

The Stone Sky by N. K. Jemisin (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

Our congrats to N. K. Jemisin and all the other nominees.

- Amberlough by Lara Elena Donnelly (Tor)

- The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter by Theodora Goss (Saga)

- Spoonbenders by Daryl Gregory (Knopf; riverrun)

- Six Wakes by Mur Lafferty (Orbit US)

- Jade City by Fonda Lee (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- Autonomous by Annalee Newitz (Tor; Orbit UK 2018)

Locus has the full list of winners in all categories.

With this win, Jemisin has made it onto our Award Winning Books by Women Authors list for the 4th time.

What do you think of this result?

2017 Shirley Jackson Award Nominees

The nominees for the 2017 Shirley Jackson Award have been announced. The noms in the novel category are:

- Ill Will by Dan Chaon

- The Bone Mother by David Demchuk

- The Changeling by Victor Lavalle

- The Hole by Hye-young Pyun

- The Night Ocean by Paul La Farge

The Shirley Jackson Awards are voted upon by a jury of professional writers, editors, critics, and academics, with input from a Board of Advisors. The awards are given for the best work published in the preceding calendar year in the following categories: Novel, Novella, Novelette, Short Story, Single-Author Collection, and Edited Anthology. You can see the complete list of noms in all categories at LOCUS.

Our congrats to all the nominees! What do you like from this list? Any surprise inclusions?

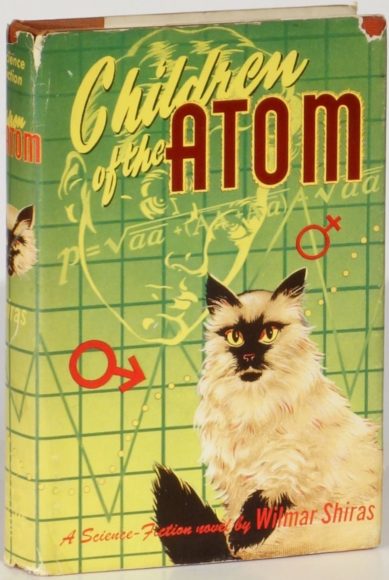

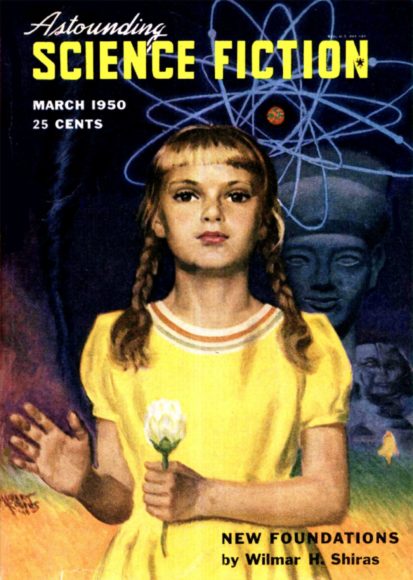

Reading the Pulps 10: “In Hiding” by Wilmar H. Shiras

“In Hiding” originally appeared in the November 1948 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction. You can find this story in these books, which include:

- Children of the Atom by Wilmar H. Shiras (collection)

- The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1949 edited by Bleiler & Dikty

- Children of Wonder edited by William Tenn

- The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume 2B edited by Ben Bova

- The Great SF Stories 10 (1948) edited by Asimov & Greenberg

Warning: This column contains mild spoilers

I just finished listening to the new audiobook edition of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume 2B. “In Hiding” turned out to be my favorite story in the collection. I don’t think I’ve read it before, although it feels vaguely familiar. And I had no memory of ever encountering the author, Wilmar H. Shiras, before. It turns out Wilmar was a woman, making her only the third woman writer in the first three volumes of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame.

“In Hiding” is a quiet story about a boy who is so smart that he has to hide his intelligence from other kids and grown-ups. I thought it a remarkable story, and so did the readers of Astounding Science-Fiction back in November 1948. “In Hiding” scored first place in “The Analytical Laboratory,” with an average score of 1.54, meaning most readers put it at the top of their list. That doesn’t happen often. John W. Campbell, the editor had this to say:

Wilmar H. Shiras sent in her first science fiction story, “In Hiding.” I liked it and bought it at once. Evidently, I was not alone in liking it: it has made an exceptional showing in the Lab here—the sort of showing, in fact, that Bob Heinlein, A. E. van Vogt, and Lewis Padgett made with their first yarns. I have reason to believe we’ve found a new front-rank author. Incidentally, there’s a sequel to “In Hiding” coming up in the March issue.

Shiras wrote two more stories for Campbell, “Opening Doors” (March 1949) and “New Foundations” (March 1950). In 1953 Shiras came out with Children of the Atom from Gnome Press by including the three Astounding stories and writing two more to create a collection. Although this book has been reprinted many times over the years, it’s not well-known, and Wilmar H. Shiras only wrote a handful of other stories, including three for Ted White’s Fantastic in the early 1970s. It’s a shame that Campbell was wrong about her, and she didn’t become a major science fiction writer. Wikipedia has damn little about Shiras. She got married at 18, had two boys and three girls. Children of the Atom is the main reason she is remembered, and only by a few old fans.

I found “In Hiding” to be a philosophically insightful science fiction story because of how Shiras dealt with the human mutant theme. There are some who claim (without documentation) that Children of the Atom inspired Stan Lee and Jack Kirby to create X-men comics. After the atomic bomb in 1945, radiation was used for all kinds of miracle mutations in comics, pulps, books, television shows, and movies. Radiation caused insects to grow as big as dinosaurs and for people to develop superpowers. Shiras took a quieter approach. Parents working at an atomic plant conceived mutant children with very high IQs. Normal looking, but very smart. I found that much more appealing than silly stories of oddities with superpowers.

I don’t know why, but science fiction has a long history of imagining Humans 2.0, and they invariably give our replacements telepathy and other psychic powers. I just don’t see that happening. Psi-powers are obviously borrowed from stories of gods, angels, and other magical beings in myths. Isn’t prayer telepathy with God? Don’t angels and demons teleport? Aren’t god-like beings always using telekinesis to act powerfully? I find it psychologically lame that SF writers assume evolution will lead to such talents. Superpowers appeal to the child in us. We want reality to be magical — it’s not.

Shiras takes a different approach, one I feel is more adult. Radiation can cause mutations. Sadly, most would be unwanted physical changes. But, Shiras suggests just a bump in smarts. Not god-like super-knowledge, but children smarter than average. In her stories, it’s implied the orphan children of the atomic plant workers have IQs greater than 150. They are orphans because the plant blows up.

“In Hiding” is about Tim, a boy a school psychologist discovers is a lot smarter than his B average grades imply. Over time the psychologist gains the confidence of the boy and learns Tim pretends to be a normal kid because he discovered at a very early age that other people, young or old, resents intelligence greater than theirs. Tim hides. He is raised by his grandparents who expect him to be well-behaved and quiet, and when he is, allows Tim to have privacy and a workshop in an old barn. By using the mail, and pseudonyms, Tim creates secret personalities that pursue various hobbies, conducts science experiments, breeds cats, completes college correspondence courses, sells stories to magazines, and writes articles for journals.

Science fiction has speculated about Homo superior or superior aliens since the 19th century. Almost always they imagine big heads and ESP. I think evolution is obviously working towards increased intelligence and self-awareness. I believe AI machines will be the next rung on the evolutionary ladder, but I also assume it is possible humans could undergo mutations that will lead to a new and improved biological species. But what is better? Marvel Comics mutants appeal to the child in us. What improvements would rational adults hope for? What new species of humans would have better adaptations for our current reality?

I’d say a species that is smart enough to live in cooperation with nature, one that doesn’t cause endless wars, mass extinctions, and poisons the ecosystem. Science fiction and comic books can’t seem to conceive of that. If Wilmar H. Shiras had continued with her series, she might have. Science fiction shines at imagining dystopias but fails at speculating about utopias. Billions plan to go to heaven, but the most complete description of heaven in The Bible sounds like hell to me.

It’s sadly ironic, but Wilmar H. Shiras has been in hiding all these years.

2018 Arthur C. Clarke Award Shortlist

The shortlist for the Arthur C. Clarke Award for best science fiction novel for 2018 have been announced. They are:

- Sea of Rust by C. Robert Cargill (Gollancz)

- Dreams Before the Start of Time by Anne Charnock (47North)

- American War by Omar El Akkad (Picador)

- Spaceman of Bohemia by Jaroslav Kalfar (Sceptre)

- Gather the Daughters by Jennie Melamed (Tinder Press)

- Borne by Jeff VanderMeer (4th Estate)

The winner will be announced July 18, 2018 and will be presented with a check for £2018.00 and the award itself, a commemorative engraved bookend.

So what do you think of this list? Any surprises for you? Which is your pick to win?

2018 Locus Awards Finalists

The finalists for the 2018 Locus Awards have been announced. Here they are for the novel categories:

- Persepolis Rising by James S.A. Corey (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- Walkaway by Cory Doctorow (Tor; Head of Zeus)

- The Stars Are Legion by Kameron Hurley (Saga; Angry Robot UK)

- Provenance by Ann Leckie (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- Raven Stratagem by Yoon Ha Lee (Solaris US; Solaris UK)

- Luna: Wolf Moon by Ian McDonald (Tor; Gollancz)

- Seven Surrenders by Ada Palmer (Tor; Head of Zeus)

- New York 2140 by Kim Stanley Robinson (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- The Collapsing Empire by John Scalzi (Tor US; Tor UK)

- Borne by Jeff VanderMeer (MCD; HarperCollins Canada; Fourth Estate)

- The Stone in the Skull by Elizabeth Bear (Tor)

- City of Miracles by Robert Jackson Bennett (Broadway; Jo Fletcher)

- Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruin of Ymr by John Crowley (Saga)

- The House of Binding Thorns by Aliette de Bodard (Ace; Gollancz)

- The Ruin of Angels by Max Gladstone (Tor.com Publishing)

- Spoonbenders by Daryl Gregory (Knopf; riverrun)

- The Stone Sky by N.K. Jemisin (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- Jade City by Fonda Lee (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- The Delirium Brief by Charles Stross (Tor.com Publishing; Orbit UK)

- Horizon by Fran Wilde (Tor)

- The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden (Del Rey)

- The City of Brass by S.A. Chakraborty (Harper Voyager US)

- Amberlough by Lara Elena Donnelly (Tor)

- Winter Tide by Ruthanna Emrys (Tor.com Publishing)

- The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter by Theodora Goss (Saga)

- The Art of Starving by Sam J. Miller (HarperTeen)

- Autonomous by Annalee Newitz (Tor; Orbit UK 2018)

- Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders (Random House; Bloomsbury)

- An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon (Akashic)

- Amatka by Karin Tidbeck (Vintage)

- Tool of War by Paolo Bacigalupi (Little, Brown)

- In Other Lands by Sarah Rees Brennan (Big Mouth House)

- The Dragon with a Chocolate Heart by Stephanie Burgis (Bloomsbury; Bloomsbury USA)

- Chalk by Paul Cornell (Tor.com Publishing)

- Buried Heart by Kate Elliott (Little, Brown)

- A Skinful of Shadows by Frances Hardinge (Macmillan; Amulet)

- Frogkisser! by Garth Nix (Scholastic; Allen & Unwin; Piccadilly)

- Akata Warrior by Nnedi Okorafor (Viking)

- Shadowhouse Fall by Daniel José Older (Levine)

- The Book of Dust: La Belle Sauvage by Philip Pullman (Knopf; Fickling UK)

For the complete list of noms in all categories check out the official press release from Locus. Winners will be announced during the Locus Awards Weekend in Seattle WA, June 22-24, 2018; Connie Willis will MC the awards ceremony. Our congratulations to all the nominees!

What do you think of these lists? Any surprises? Any favorites?

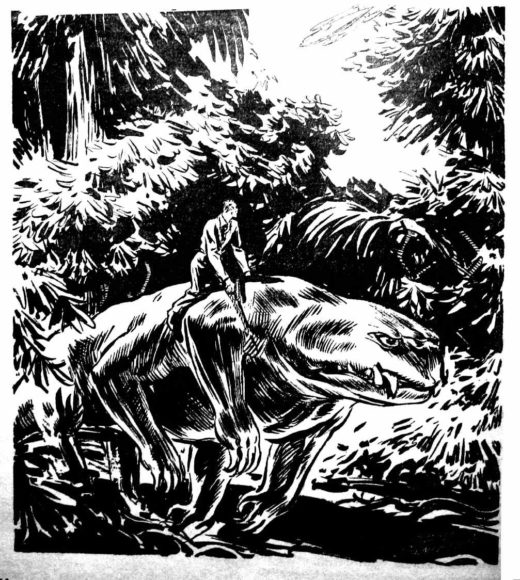

Reading the Pulps 9: “Co-Operate—Or Else!” by A. E. van Vogt

“Co-Operate—Or Else!” originally appeared in the April 1942 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction. You can find this story in these anthologies, which include:

- The Great SF Stories 4 (1942) edited by Asimov & Greenberg

- Futures Past: The Best Short Fiction of A. E. van Vogt

- The War Against the Rull by A. E. van Vogt (fix-up novel)

Warning: This column contains minor spoilers

“Co-Operate—Or Else!” begins with a bang and keeps exploding with action. Readers feel like they’ve been thrown into a climax of an adventure novel as Professor Jamieson hangs from an anti-gravity disc high above a jungle planet. (Think high tech parachute.) We learn later in the story that his spaceship has been destroyed by one violent alien creature, an ezwal, and Jamieson is the sole survivor from a crew of over hundred humans. The ezwal, a giant six-legged creature stands on top of the anti-gravity disc trying to kill Jamieson as they float towards the surface of a deadly planet. Later on another race of aliens, the Rull, try to kill both of them, thus the title. This is a terrific start to a science fiction adventure.

Every time I read a science fiction story about aliens I wonder if the author will present a new view of aliens. I’ve been consuming science fiction for sixty years and it’s been a long time since I encountered anything different. Have SF writers imagined all the possibilities? One of my retirement projects is reading all the great short stories in the science fiction genre. I’m systematically going through the annual best-of-the-year anthologies starting in 1939 as well as reading the outstanding retrospective anthologies that preserve the most distinctive science fiction stories from the last four hundred years.

I’ve been keeping a mental list of alien archetypes. It’s starting to feel like that list will be finite because of the constant reuse of the same old forms. In the next decade, I’ll be reading a couple thousand stories which should give me a good statistical example to see if I’m right.

In counting types of imagined aliens, I’m wondering if it should be a list of discrete examples or a list of spectrums. Should alien invaders be subcategorized into various kinds of invading beings or just a spectrum from ultimate nightmares to ultimate BAFFs? Should we create a database of alien taxonomies or just use a spectrum from completely incomprehensible to just like us? We could divide alien relationships into enemies, allies, traders, friends, rulers, subjects, equals, etc., or give a numerical score of 0 for no communication possible to 10 for aliens with whom we develop a telepathic symbiotic relationship.

Science fiction writers have a hard time portraying aliens without using human attributes. “The Martian Odyssey” was such an astounding story in 1934 because Stanley Weinbaum described aliens by their bizarre behaviors. Concurrent with Weinbaum in the 1930s Olaf Stapledon in Star Maker, presented most kinds of aliens we’d see in science fiction for decades to come.

Science fiction writers work hard to imagine what a first contact will reveal. Have they pre-imagined all the possibilities? I sometimes wonder if they have, but I’m going to assume when we actually encounter aliens they will be everything we never imagined. Of course, they might be a black swan, and we’ll hit our heads like a V-8 commercial and say, “That’s so obvious, why didn’t we ever think of that?”

Everyone knows we have mental receptors for recognizing characteristics of sexual attraction in other humans. What if we also have receptors for archetypes in fiction? And even specific ones for science fiction? And what if those archetypes are finite because of hardwired neural limitations?

I’m going to use “Co-Operate—Ore Else!” because it triggered several archetypes as I read. I’m learning from old science fiction why we psychologically respond to science fiction. I’m sure how we imagine aliens in science fiction is directly related to how we pre-imagined people from other cultures. Science fiction often connects deeply with our xenophobia. The trouble is science fiction writers need to imagine beings that aren’t like us, and that’s very hard to do. Look how long we’ve taken to recognize intelligence in other Earthly animals.

Great science fiction lies between the gosh-wow thrill of a Buck Rogers serial and the hard precise mathematically reality of the latest NASA probe. “Co-Operate–Or Else!” reminds me of so many science fiction stories that came later. Picture Captain Kirk in an Enemy Mine conflict on a Deathworld planet.

Back in the 1940s A. E. van Vogt was a superstar of science fiction pulp writers. Many claim The Golden Age of Science Fiction began in July 1939 with his story “The Black Destroyer.” And anyone who has read that story is reminded of the film Alien because of the monster who sneaks onto the ship. Plus, the captain and crew will remind them of Forbidden Planet and Star Trek. Back in 1966 when Star Trek premiered, I thought it original because I had only been reading science fiction for four years. But in the fifty plus years since, I keep discovering how it riffed off Golden Age science fiction. When I read even older science fiction, I discovered the Golden Age writers weren’t original either.

Science fiction writers keep repeating certain concepts while using the same writing techniques. Both the concepts and the techniques can be considered archetypes that go way back into our collective consciousness. Because science fiction works off our past, it has a very difficult time imagining beings we’ve never encountered.

Fantastic Action Adventure might be the first archetype we’re dealing with in this van Vogt story. I doubt Homer was the first to use it or George Lucas the last, yet elements of The Iliad, The Odyssey, and Star Wars have striking similarities. Joseph Campbell has covered that thoroughly. Heroic conflict in strange lands with fantastic creatures can’t be claimed by science fiction but they are part of its evolutionary development.

Also common to all fiction is the Cliffhanger-Escape technique. Van Vogt throws his characters into a series of traps that promise certain death only to have them escape. The new Lost in Space often featured two or three cliffhangers with escapes in each episode. Combining fast action with repeated escapes was the standard plot structure of most pulp fiction stories. So, what archetypes of storytelling are unique to science fiction?

Two that van Vogt uses in this story effectively is the Not Like Us Alien and the Ultimate Threat Alien. The ezwal are an intelligent race of beings that don’t use technology. The unnamed telepathic ezwal in this story wants to kill humans for invading their planet, treating his species like food animals, and not recognizing their form of intelligence. The Rull are a species of intelligent being that use technology and travel from galaxy to galaxy destroying all intelligent species. They also eat humans which makes them our ultimate enemy. Cannibalism has always been the pinnacle of horror for describing human enemies. The ezwal are like us getting to talk to an octopus about why we eat them. Van Vogt creates the Rull by imagining a top-level predator who would eat us.

We learn later in the story that Professor Jamieson was bringing the ezwal to Earth to prove their species were intelligent so the federation of over 4,800 worlds with indigenous intelligent species would change their policy on Carson’s Planet, the homeworld of the ezwal. Just before the story began the ezwal escaped aboard ship and killed every human except Jamieson and destroyed the spaceship. “Co-Operate—Or Else!” is about Jamieson’s struggle to convince the ezwal to change his mind about humans. He also wants to convince the ezwal to combine forces, first to survive the deadly planet, and later to fight the Rull. He tells the ezwall his species must join their federation to war against the Rull or else all the species in our galaxy will be destroyed. The ezwal wants to ally his race with the Rull to destroy the humans, and Jamieson struggles to convince the ezwal the Rull have no allies. How many times have we seen this plot?

Nostalgia is an archetype used by all types of fiction. “Co-Operate—Or Else!” doesn’t use it directly, except that I imagine 1942 SF readers were reminded of Edgar Rice Burroughs planetary adventures, or earlier science fiction classics like “A Martian Odyssey.” It’s funny, but much of modern film/TV science fiction is strongly nostalgia driven. Fans can’t let go of Star Trek, Star Wars, or even Lost in Space. I suppose rebooting classic science fiction TV shows only reinforces my theory that there’s a limited number of science fictional archetypes that appeal to us.

If you analyze all the science fiction books, movies and television shows about alien contact, we could sort them into a set of categories. War of the Worlds is not the first alien invasion story, but probably the one most people think defined the archetype. It also illustrates xenophobic science fiction. Tweel in “The Martian Odyssey” is probably how most older SF readers remember the E.T. category of a good alien. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers defines the ultimate threat alien to many readers. These are aliens we can kill without ethical consequences. That is until Orson Scott Card refined the category with Ender’s Game/Speaker for the Dead/Xenocide. The ezwal reminds me of the one-with-nature aliens in Avatar.

“Co-Operate—Or Else!” suggests another archetype – nonhuman intelligence. In most science fiction stories aliens are pretty much like us. Few authors work to convey truly alien aliens who perceive reality much differently from humans. The ezwal claims humans use of technology is a crutch. The ezwal are like dolphins, being intelligent without building things. The ezwal tells Jamieson that technology made them blind to their superior mental abilities. The ezwal use telepathy to survive and evolve. Does that make them superior aliens? Quite often in science fiction, we define superior beings by their ability to use psychic powers. But isn’t that the same thing we did with gods and God? We have a very limited ability to imagine beings more advanced than us.

I just finished the new 10-part Lost in Space on Netflix. The aliens in this show are intelligent robots. Are they evil beings out to exterminate humans, or are there reasons their violence against us could be ethical? Because fiction often wants pure enemies to destroy without moral qualms, science fiction often invents Borg, Bezerkers, Bugs, or Buggers to kill without empathy. But isn’t this like video games seeking kill thrills?

Van Vogt covers a lot of ground in “Co-Operate—Or Else!” Jamieson wants humans and ezwal to coexist. But he also claims there will be aliens who want to exterminate all other intelligent beings and they should be made extinct. Is that the true spectrum of how we imagine aliens — from those we should kill, to those we should befriend? In Roadside Picnic, Russian SF writers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky imagined aliens we couldn’t comprehend. who were neither a threat nor potential friend, because we were completely inconsequential to them.

“Co-Operate—Or Else!” is a fairly early SF story. As I continue to read through the years of science fiction I expect to find a variety of aliens, yet I worry I won’t find anything I haven’t encountered before. I feel challenged to seek authors who can escape the event horizon of our collective imaginations. But is that possible? I plan to keep a spreadsheet of SF archetypes, and maybe that will eventually describe the scope of science fiction.

JWH

Full Details

Full Details