2018 Prometheus Award Finalists

The Libertarian Futurist Society has announced the finalists for the 2018 Prometheus Award, honoring pro-freedom works published in 2017.

The Libertarian Futurist Society has announced the finalists for the 2018 Prometheus Award, honoring pro-freedom works published in 2017.

- Drug Lord by Doug Casey and John Hunt (High Ground)

- The Powers of the Earth by Travis J. I. Corcoran (Morlock)

- Torchship Trilogy by Karl K. Gallagher (Kelt Haven)

- Darkship Revenge by Sarah Hoyt (Baen)

- Emergence by Ken MacLeod (Orbit)

- Artemis by Andy Weir (Crown)

The award will be presented in a ceremony during Worldcon 76, to be held August 16-20, 2018 at the McEnery Convention Center in San Jose CA. Our congrats to all the finalists! Who do you think is going to win?

Reading the Pulps 7: “The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany

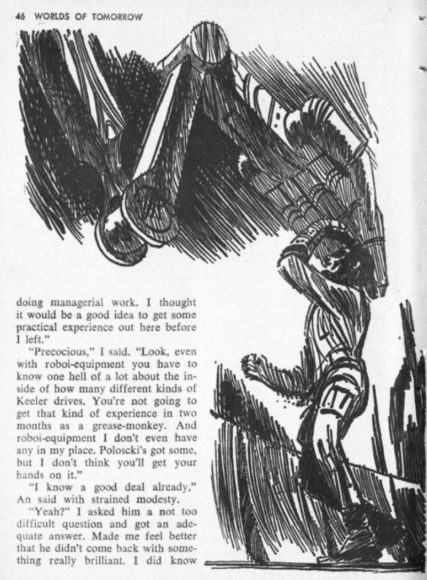

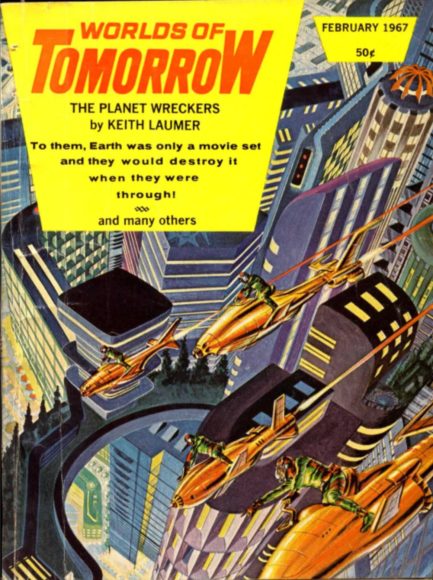

“The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany first appeared in Worlds of Tomorrow February 1967.

You might already own “The Star Pit” in one of these books:

- SF 12 edited by Judith Merril

- Driftglass by Samuel R. Delany

- The Arbor House Treasury of Great Science Fiction Short Novels edited by Robert Silverberg and Martin H. Greenberg

- Modern Classic Short Novels of Science Fiction edited by Gardner Dozois (only U.S. ebook edition of this story I know about.)

- Aye, and Gomorrah by Samuel R. Delany (Delany’s current short story collection that’s still in print.)

Warning: This column contains spoilers.

“The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany is a complex novella I’ve read several times in the last half-century. It reiterates common themes Delany dwelt on in the 1960s as a young writer. “The Star Pit” explores the emotions we feel when we discover places we can’t go but other people can. The story analyzes how dissatisfaction of not fitting in makes us want to go elsewhere.

I related to this story strongly back in 1967 because of the anguish I felt wanting to be an astronaut and learning I couldn’t. I didn’t have 20-20 vision. I didn’t understand back then why I wanted to leave the Earth. In the decades since I’ve learned that there are countless existential locations I can’t go, that others can. I’ve since learned why I was unhappy wherever I was, making this story more beautiful every time I reread it. Anyone who reads “The Star Pit” will discover analogies with their own dissatisfactions and limitations.

Have I been a life-long science fiction fan because I couldn’t go into space? I’m not part of the Millennium Falcon generation, where science fiction is pure escapist fantasy. My favorite spacecraft has always been the Gemini space capsule, something that was as down-to-Earth as a Volkswagon Beetle. My astronaut ambitions began with reading Have Space Suit – Will Travel and ended with “The Star Pit,” a period that coincided with the duration of Project Gemini in the 1960s. Of course, I didn’t know besides poor vision I completely lacked the right stuff until I encountered Tom Wolfe’s book.

Over the years I’ve read many astronaut memoirs and they’ve all taught me the same thing: I’m an earthling. Reading “The Star Pit” shows us the boundaries of our ecological existence. It reveals the dissatisfaction of not fitting in pushes us to leave, and at some point, we butt into a barrier like a guppy in an aquarium.

I’ve always read science fiction because I thought it prepared us for the future. I believed being a science fiction fan supported colonizing the solar system. Now I have doubts. What if humans can’t spread across moons, planets, and the galaxy? Is “The Star Pit” an analogy for that too?

Like Kip Russell in the Heinlein novel, I fantasized in 1967 I’d find a way into space one way or another. I was desperate to get to Mars. I didn’t really know why then. I probably assumed my religion, science fiction, demanded it. As I got older I discovered all the ways I couldn’t adjust to my environment. Was a lifetime of reading science fiction my Zoloft to ease the anxiety of never fitting in and never escaping? Or was the vicarious thrill of science fiction all I ever really needed, like a drug? Wisdom has taught me I never could have been an astronaut. I now know I would hate living in space. So, why do I still read science fiction? That answer also lies in “The Star Pit.” Delany’s words weave the allure of living on other worlds. “The Star Pit” is also an ecologarium.

Is fiction our substitute for living lives of quiet desperation? Some people want to do things in life so badly that they make it happen. Or, die trying. As a kid, I thought anything was possible, and I’d be one of those people who’d overcome all odds. I wasn’t. I just didn’t know that in 1967.

I have a thought experiment I sometimes use to see my life more clearly. I call it the Amoeba Analogy or The Microscope Perspective. Have you ever studied pond water under the microscope and watched simple multicellular animals go through their interactions? Imagine seeing your own life from above, as through a microscope lens. It’s a great way to visualize the finite limitations of our own ecologarium.

Delany starts his story with a description of an ecologarium, a reoccurring analogy in this story:

Two glass panes with dirt between and little tunnels from cell to cell: when I was a kid I had an ant colony.

But once some of our four-to-six-year-olds built an ecologarium with six-foot plastic panels and grooved aluminum bars to hold corners and top down. They put it out on the sand.

There was a mud puddle against one wall so you could see what was going on underwater. Sometimes segment worms crawling through the reddish earth hit the side so their tunnels were visible for a few inches. In hot weather the inside of the plastic got coated with mist and droplets. The small round leaves on the litmus vines changed from blue to pink, blue to pink as clouds coursed the sky and the pH of the photosensitive soil shifted slightly.

The kids would run out before dawn and belly down naked in the cool sand with their chins on the backs of their hands and stare in the half-dark till the red mill wheel of Sigma lifted over the bloody sea. The sand was maroon then, and the flowers of the crystal plants looked like rubies in the dim light of the giant sun. Up the beach the jungle would begin to whisper while somewhere an ani-wort would start warbling. The kids would giggle and poke each other and crowd closer.

Then Sigma-prime, the second member of the binary, would flare like thermite on the water, and crimson clouds would bleach from coral, through peach, to foam. The kids, half on top of each other now, lay like a pile of copper ingots with sun streaks in their hair—even on little Antoni, my oldest, whose hair was black and curly like bubbling oil (like his mother’s), the down on the small of his two-year-old back was a white haze across the copper if you looked that close to see.

More children came to squat and lean on their knees, or kneel with their noses an inch from the walls, to watch, like young magicians, as things were born, grew, matured, and other things were born. Enchanted at their own construction, they stared at the miracles in their live museum.

A small, red seed lay camouflaged in the silt by the lake/puddle. One evening as white Sigma-prime left the sky violet, it broke open into a brown larva as long and of the same color as the first joint of Antoni’s thumb. It flipped and swirled in the mud a couple of days, then crawled to the first branch of the nearest crystal plant to hang exhausted, head down, from the tip. The brown flesh hardened, thickened, grew black, shiny. Then one morning the children saw the onyx chrysalis crack, and by second dawn there was an emerald-eyed flying lizard buzzing at the plastic panels. “

Oh, look, Da!” they called to me. “It’s trying to get out!”

Samuel Delany was an active organism himself back in the 1960s. He traveled far and wide. “The Star Pit” is a story about people like him who wanted to go further and do more but couldn’t. Before I read this story, I wanted to be like Wally Schirra and fly in the Gemini space capsule. In “The Star Pit” we meet a kid who wants to be Golden and travel to other galaxies.

Delany uses my Amoeba Analogy with his ecologarium, reminding readers we are part of an ecology. The structure of “The Star Pit” is like Russian Matryoshka nesting dolls. Delany loves recursive or circular plots, the most famous of which is used in Empire Star.

Vyme, age 42, is the largest of the nesting dolls, and our protagonist. Vyme is a black man, which was uncommon back then in science fiction. I didn’t know it at the time, but Delany was black and gay. Delany was only in his twenties when he wrote this story, so I imagine he was projecting himself as an older man in Vyme. Vyme is a drunk, and failed father. My own father was an alcoholic and failed dad too, which is another personal reason why I relate to this story. The main events in “The Star Pit” take place years after the beautiful introduction above. The Star Pit is an artificial world where intergalactic travelers come and go at the edge of the galaxy. Vyme owns a garage for spaceships and helps wayward kids get work to atone for abandoning his own children.

In Delany’s fictional universe, most humans go crazy if they get twenty-thousand light years beyond the galaxy’s edge, and die at twenty-five thousand. Only a few humans have the psychological make-up to travel across the void between galaxies. They are called Golden. This is the analogy with the average citizen of the 1960s and astronauts, but for many other things too. This story contains Ptolemaic circles within circles of analogies.

Another nesting doll in this story is Ratlit, a thirteen-year-old precocious kid who has already published a novel. Vyme sees Ratlit in himself, and we also know that Delany was a precocious kid who wrote a novel too. Ratlit hates the Golden because he wants to travel to other galaxies (Delany’s metaphor for racism?). Ratlit is in love with Alegra, a girl born with psychic powers and an addiction to an exotic drug from another galaxy. She’s a couple years older than Ratlit, and he uses her to view the worlds on distant galaxies because she can project imagery from the minds of the Golden.

Between the ages of Ratlit and Vyme is Sandy, another man who fails at marriage. Marriages in “The Star Pit” are complex group affairs, so Vyme and Sandy fail to fit into their societies. They are loners. Sandy also sees Ratlit as a younger version of himself and realizes Ratlit will eventually hurt Vyme and tries to protect him. Vyme and Sandy witness two Golden fight, with one killing the other. The victor gives the dead Golden’s spaceship to Sandy and Vyme. Ratlit wants them to give him the spaceship so he can give it to a Golden that’s come between him and Alegra.

Vyme wants to help Ratlit, and Sandy wants to protect Vyme. Each of them knows they are trapped by limitations, each of them tries to help the other get beyond those limits. Vyme, Sandy, and Ratlit each feel they are the most wisely experienced despite their ages. I assume Delany sees these three characters as himself at different ages. And I’m not sure if all the characters aren’t Delany in some ways, even the mean and dumb Golden.

The last doll in the nesting is An, for Androcles, a Golden. He has another ecologarium, this one a small sphere he wears around his neck, with a tiny microscope built onto it. He lets Vyme look at it:

I looked through the brass eyepiece.

I’d swear there were over a hundred life forms with a five to fifty stages each: spores, zygotes, seeds, eggs, growing and developing through larvae, pupae, buds, reproducing through sex, syzygy, fission. And the whole ecological cycle took about two minutes.

Spongy masses like red lotuses clung to the air bubble. Every few seconds one would expel a cloud of black things like wrinkled bits of carbon paper into the gas where they were attacked by tiny motes I could hardly see even with the lens. Black became silver. It fell back to the liquid like globules of mercury, and coursed toward the jelly that was emitting a froth of bubbles. Something in the froth made the silver beads reverse direction. They reddened, sent out threads and alveoli, until they reached the main bubble again as lotuses.

The reason the lotuses didn’t crowd each other out was because every eight or nine seconds a swarm of green paramecia devoured most of them. I couldn’t tell where they came from; I never saw one of them split or get eaten, but they must have had something to do with the thorn-balls—if only because there were either thorn-balls or paramecia floating in the liquid, but never both at once.

A black spore in the jelly wiggled, then burst the surface as a white worm. Exhausted, it laid a couple of eggs, rested until it developed fins and a tail, then swam to the bubble where it laid more eggs among the lotuses. Its fins grew larger, its tail shriveled, splotches of orange and blue appeared, till it took off like a weird butterfly to sail around the inside of the bubble. The motes that silvered the black offspring of the lotus must have eaten the parti-colored fan because it just grew thinner and frailer till it disappeared. The eggs by the lotus would hatch into bloated fish forms that swam back through the froth to vomit a glob of jelly on the mass at the bottom, then collapse. The first eggs didn’t do much except turn into black spores when they were covered with enough jelly.

All this was going on amidst a kaleidoscope of frail, wilting flowers and blooming jeweled webs, vines and worms, warts and jellyfish, symbiotes and saprophytes, while rainbow herds of algae careened back and forth like glittering confetti. One rough-rinded galoot, so big you could see him without the eyepiece, squatted on the wall, feeding on jelly, batting his eye-spots while the tide surged through quivering tears of gills.

I blinked as I took it from my eye.

“That looks complicated.” I handed it back to him.

“Not really.” He slipped it around his neck. “Took me two weeks with a notebook to get the whole thing figured out. You saw the big fellow?”

“The one who winked?”

“Yes. Its reproductive cycle is about two hours, which trips you up at first. Everything else goes so fast. But once you see him mate with the thing that looks like a spider web with sequiris—same creature, different sex—and watch the offspring aggregate into paramecia, then dissolve again, the whole thing falls into—”

“One creature!” I said. “The whole thing is a single creature!”

In many, if not all of Delany’s stories in the 1960s, he gives us characters who anguish over their limitations and resent people who have already done things they hope to do. His characters often feel their cherished uniqueness challenged when they meet others who mirror their talents. Ultimately, even the Golden have limitations. They discover lifeforms that can travel between universes. The lesson of this tale is no matter how far you can go, there are always others who can go further, and there are always further places to go.

When I read “The Star Pit” in 1967 I suffered because I couldn’t go into space. Delany was a black gay man who couldn’t go places in my white world where I could. The funny thing is, there were endless exotic places on Earth we both could have gone that were just as far out as anything he wrote or I read in science fiction.

Science fiction today is consumed as a kind of virtual reality for enjoying space travel fantasies. I still read hard science fiction stories where SF writers try to imagine how colonizing space is possible, but they are less common. Why do we want to leave Earth? Are we dissatisfied with life here? Or do we need to go further, to places we currently can’t go?

Is a Sci-Fi fan’s desire to live in outer space any different from a Christian’s desire to dwell in heaven? Or any more realistic? Aren’t most of the places we anguish over not being able to reach also not real anyway? Aren’t we all rejecting an acutely real life on Earth? Isn’t the ultimate point of this story to teach us how stay and coexist in our own ecologarium?

JWH

The Kitschies: 2017 Red Tentacle and Golden Tentacle Finalists

After a year long hiatus the Kitschies are back. The finalists for the 2017 Red Tentacle and Golden Tentacle awards have been announced!

The Kitschies reward the year’s most progressive, intelligent and entertaining works that contain elements of the speculative or fantastic published in the UK.

- Black Wave by Michelle Tea (& Other Stories)

- The Rift by Nina Allan (Titan)

- We See Everything by William Sutcliffe (Bloomsbury)

- Fever by Deon Meyer, translated by L. Seegers (Hodder)

- City of Circles by Jess Richards (Hodder)

- How Saints Die by Carmen Marcus (Harville Secker)

- Hunger Makes the Wolf by Alex Wells (Angry Robot)

- Age of Assassins by RJ Barker (Orbit)

- The Black Tides of Heaven by J. Y. Yang (Tor.com)

- Mandelbrot the Magnificent by Liz Ziemska (Tor.com)

Our congrats to all the finalists! What do you think of this crop of books? Anything stand out to you? Let us know in the comments.

2017 James Tiptree, Jr. Award Winner

The 2017 James Tiptree, Jr. Award, for works of speculative fiction which explore and expand gender, has been announced.

The 2017 James Tiptree, Jr. Award, for works of speculative fiction which explore and expand gender, has been announced.

Winner:

- Who Runs the World? by Virginia Bergin (Macmillan)

Honor List:

- “Don’t Press Charges and I Won’t Sue” by Charlie Jane Anders (Global Dystopias)

- Dreadnought and Sovereign by April Daniels (Diversion)

- The Devourers by Indra Das (Del Rey)

- An Excess Male by Maggie Shen King (Harper Voyager)

- Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado (Gray Wolf)

- An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon (Akashic)

- The Black Tides of Heaven and The Red Threads of Fortune by JY Yang (Tor)

You can read more details about each selection on the official Tiptree website.

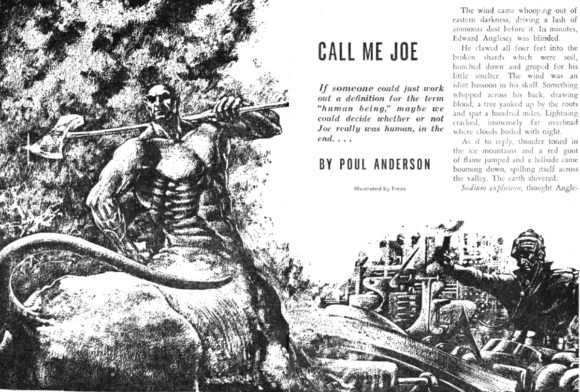

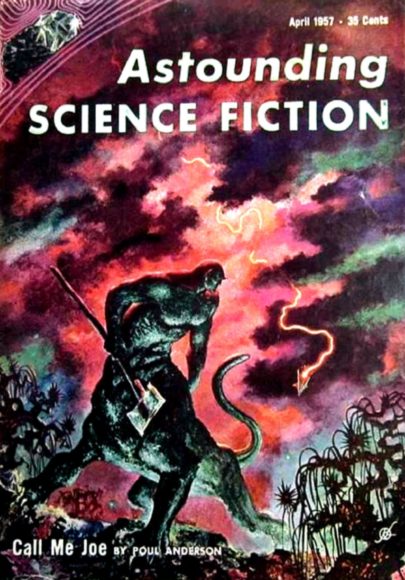

Reading the Pulps 6: “Call Me Joe” by Poul Anderson

Read it now: Astounding Science Fiction April 1957 (from the Luminist League)

You might already own “Call Me Joe” in one of these anthologies:

- Best Science Fiction Stories and Novels 9th Series edited by T. E. Dikty

- A Century of Science Fiction edited by Damon Knight

- The Science Fiction Hall of Fame v. 2A edited by Ben Bova

- The Great SF Stories #19 (1957) edited by Asimov & Greenberg

- Masterpieces: The Best Science Fiction of the Century edited by Orson Scott Card

- Call Me Joe: The Collected Works of Poul Anderson #1

- Call Me Joe – 99 cent eBook at Amazon

Warning: This column contains spoilers.

I’ve been struggling for days to write this essay. I torture myself with self-analysis wanting to know why I keep reading these old stories. I work to build a framework for critical judgment of science fiction that keeps collapsing. I keep relearning that few people read these old stories anymore, which makes me keep asking: “Why am I making this effort?” This leads to pages and pages of theories, eventually leading to the realization the answers are too long for a single essay. So, I’ve decided to just let them leak out while I discuss a series of stories over the next few months.

“Call Me Joe” by Poul Anderson was first published in 1957 and was selected by the Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) for inclusion in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume 2B edited by Ben Bova. Volume One and 2A have been released on audio and volume 2B is due April 10th. Listening to all these classic science fiction tales is a joy for me, but I’m haunted by the question: “Will anyone care about these old stories when old fans like me die off?”

“Call Me Joe” begins:

The wind came whooping out of eastern darkness, driving a lash of ammonia dust before it. In minutes, Edward Anglesey was blinded.

He clawed all four feet into the broken shards which were soil, hunched down and groped for his little smelter. The wind was an idiot bassoon in his skull. Something whipped across his back, drawing blood, a tree yanked up by the roots and spat a hundred miles. Lightning cracked, immensely far overhead where clouds boiled with night.

As if to reply, thunder toned in the ice mountains and a red gout of flame jumped and a hillside came booming down, spilling itself across the valley. The earth shivered.

Sodium explosion, thought Anglesey in the drumbeat noise. The fire and the lightning gave him enough illumination to find his apparatus. He picked up tools in muscular hands, his tail gripped the trough, and he battered his way to the tunnel and thus to his dugout.

It had walls and roof of water, frozen by sun-remoteness and compressed by tons of atmosphere jammed onto every square inch. Ventilated by a tiny smoke hole, a lamp of tree oil burning in hydrogen made a dull light for the single room.

Why does Edward Anglesey have four feet and a tail? And even though we are told the earth shivered, it doesn’t sound like our world at all. It’s not. We’re on Jupiter, and Edward occupies the mind of a genetically engineered animal designed to live on Jupiter. Anglesey is a man in a wheelchair working in a scientific laboratory orbiting Jupiter. With a combination of psychic powers amplified by electronic equipment Anglesey can control the being called Joe on the surface of Jupiter. When Joe is awake Edward lives in Joe’s powerful body, and when Joe sleeps Anglesey bitterly occupies his own crippled body on the space station.

In 1950s science fiction writers were imagining how humans could explore the solar system. For most writers, the gas giants were considered inhospitable to humans. Anderson wanted to find a way to explore them too. Because many science fiction writers, especially at John W. Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction assumed humans had latent psychic abilities, Anderson combined bioengineering and electronic enhanced possession to solve the problem of living on Jupiter. It’s a wonderful bit of science fictional speculation and imagination for 1957.

However, in 2018 we know there is no surface on Jupiter. We also know that humans do not have psychic powers. In 1957 “Call Me Joe” was good science fiction, in 2018 “Call Me Joe” is outdated science fiction. Modern science fiction often speculates how we could live on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, but we’ve given up on colonizing the gas giants themselves. Not all SF writers have given up on psi-powers, but no one who understands science considers ESP anything more than gimmicks for stories that appeal to childish minds.

Does this mean we should stop reading “Call Me Joe?” That’s a hard question to answer. It’s still a well-told compelling work of fiction. It’s entertaining. The first goal of writing is to sell to editors. The second goal is to sell to readers. Entertainment sells best. What makes a story last to become art involves other qualities. 99.9% of most stories don’t last. And even then, it might be overly generous to say one out of thousand stories survive the test of time.

I went to a science fiction convention this weekend looking for dealers of old books and magazines and found none. I hoped to find panels that talked about old stories and found none. Very few people read science fiction short stories anymore. For the majority of science fiction fans, they define the term by movies, television shows, games, anime, comics, role-playing, and cosplay. And I’d say most of the active science fiction readers prefer book series now. Short fiction has a declining audience.

Science fiction of 1957 is not the science fiction of 2018. In 1957 science fiction fans pursued beliefs in the future they faithfully hope science would make real. For the most part, science fiction in 2018 is a form of escape from reality. It’s a rejection of growing up. Just another fantasyland. Very little science fiction written today is about making ideas come true.

So how do we judge a dying art form? There are still science fiction writers who pursue speculation about the possible in a reality governed by science. But most fans want Star Wars. Even Star Trek has been morphed into Star Wars.

If we only consider entertainment as a measure of artistic success, popularity and sales figures are good enough yardsticks for judging. And by those measurements, the stories in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame series must have little artistic merit. This is where I’m trying to build my critical framework. Traditional art has all kinds of measures we could apply to the storytelling part of science fiction, such as how they were written, characterization, plot, theme, setting, and what they say about the times in which they were written. But what about the unique qualities of science fiction? How do we judge speculation? What makes science fiction uniquely science fiction and how do we judge it? How can we define science fiction when it becomes a catch-all for all kinds of far-out unscientific story ideas?

If we don’t consider the science in science fiction, then it’s only fiction and should be judged by the standards of all fiction. And if we do consider the science, how do we judge the science in the story, by the science of when it was written or the science of when it was read? Science fiction often speculates about realistic possibilities that eventually become probably impossibilities.

I believe “Call Me Joe” is a wonderful story about 1957 science fiction. It tells us all kinds of things about 1957 that can’t be found in history books or even Best American Short Stories 1958. If I forget that it was written in 1957, it works as a story, but the science is woefully ignorant. However, that might not be a problem for modern science fiction fans since a kind of comic book pseudo-science has taken over popular science fiction.

Science fiction has become another Disneyland. For most writers and readers, it’s always been that too. However, for a few writers and readers, it was about speculating where science had yet to statistically tabulate the odds. In 1957 there were still some long odds for psychic powers, now there’s not. Poul Anderson used those odds in a creative way. The odds haven’t played out. How do we judge his creative effort?

JWH

Reading the Pulps #5: Visual Memory and Nostalgia

Is an aspect of nostalgia an ache to see things we once owned or coveted? On Facebook, there are countless groups where members post images driven by nostalgia. At Space Opera Pulp over eleven thousand people enjoy pictures from old science fiction books and pulp magazines covers. Raypunk, which has a modern slant has over twenty-three thousand members. There are photo nostalgia groups of all kinds. I also belong to ones that remember old movies, westerns, cars, mid-century houses, graphic artists, Baby Boomer memorabilia, etc. I don’t know why, but some of the most nostalgically powerful images for me are old book and magazine covers.

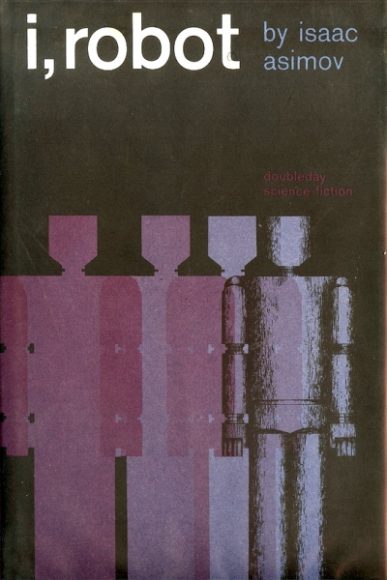

I recently created a cover gallery, “The Hardback Legacy of Astounding Science Fiction” for my blog. It was an excuse to gather .jpg images of all the first edition books that reprinted content from Astounding Science Fiction magazine (1930-1960). I love looking at artwork that illustrated old science fiction stories. For that post, I narrowed it down to hardbacks. Some people have commented they remember the same books by their paperback covers. Then last night on Young Sheldon I saw Sheldon reading a copy of I, Robot with the cover I had for the Science Fiction Book Club edition I first read. Man, that released a flood of nostalgia-chemicals in my brain. I wonder how many older viewers had a deep twinge of longing for the past when they saw that scene?

I recently created a cover gallery, “The Hardback Legacy of Astounding Science Fiction” for my blog. It was an excuse to gather .jpg images of all the first edition books that reprinted content from Astounding Science Fiction magazine (1930-1960). I love looking at artwork that illustrated old science fiction stories. For that post, I narrowed it down to hardbacks. Some people have commented they remember the same books by their paperback covers. Then last night on Young Sheldon I saw Sheldon reading a copy of I, Robot with the cover I had for the Science Fiction Book Club edition I first read. Man, that released a flood of nostalgia-chemicals in my brain. I wonder how many older viewers had a deep twinge of longing for the past when they saw that scene?

Are the covers we remember most the ones we saw first?

Shown above, is how I remember I, Robot. When I look at all the other covers for I, Robot they don’t tweak my nostalgia like this SFBC edition cover. I even wonder if I’m nostalgic for the stories at all, but instead long to see the book I once held while enjoying the stories?

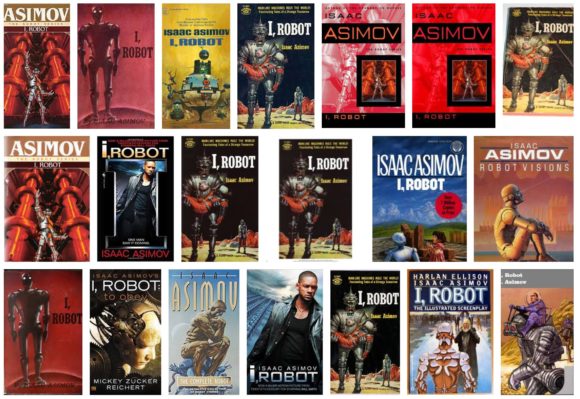

I use two ways to find cover images. The first one, which is the quickest method, is with a Google search then clicking the image tab. The results look like this:

Google tends to get the most popular images, and often throws in stuff that’s not related. The way below was created using ISFDB.org. It requires typing a query into its database, and sometimes it takes a little skill. Regular use will reveal it’s tricks. First, find the main entry for the book you want by typing in the title and then selecting “Fiction Titles.” Hit Go. Click the title link to the proper entry. Then scroll down to the bottom of that list and click on all “View all covers for …” Here are the early covers for I, Robot in publication order. Click on the link to see all.

This got me to thinking. Is a big aspect of nostalgia related to what we owned or wanted to own when we were teens? Even if its something popular before our teen years? I turned 13 the year the Ford Mustang and Plymouth Barracuda came out in 1964. So images of 1960s muscle cars light up my nostalgia neurons. Generally, pictures of anything that happened in the 1960s turn on my nostalgia. But so do images from 1930s movies and 1940s pulp magazines, things that came out way before I was born. What explains that? They are past pop culture I learned to love in my teens. Why do we imprint so strongly what we experienced from age 10-20? Why don’t I have nostalgia for stuff I discovered in my forties? Maybe I will in my eighties.

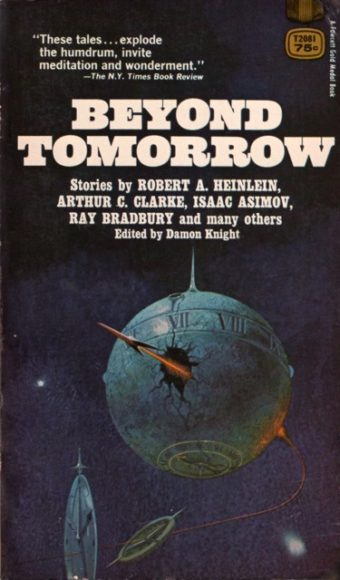

My friend Mike told me how he loved a paperback copy of Beyond Tomorrow, a paperback anthology edited by Damon Knight, which he said he read to pieces. That made me remember something else. I love covers from many science fiction books, but I’m always partial to the editions I first read.

My friend Mike told me how he loved a paperback copy of Beyond Tomorrow, a paperback anthology edited by Damon Knight, which he said he read to pieces. That made me remember something else. I love covers from many science fiction books, but I’m always partial to the editions I first read.

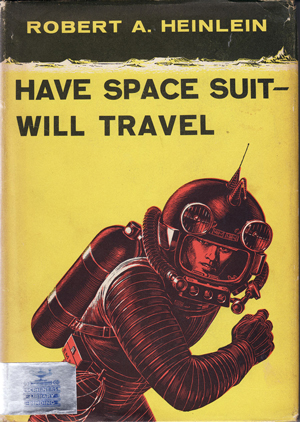

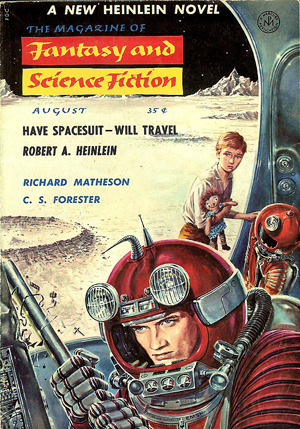

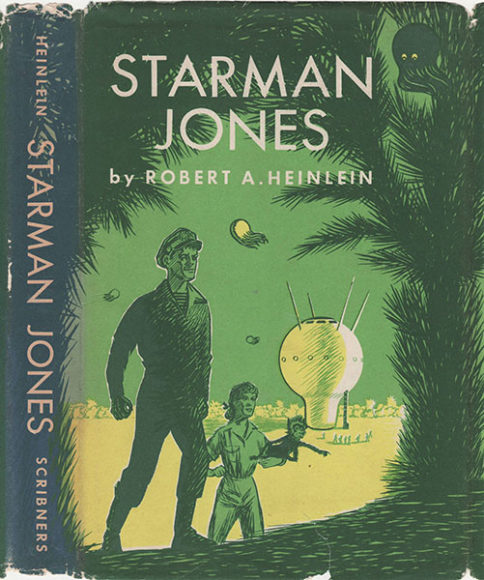

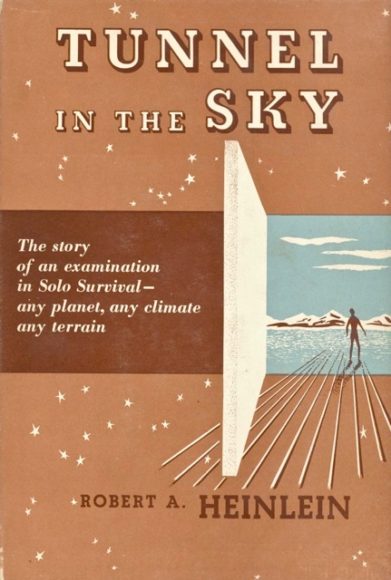

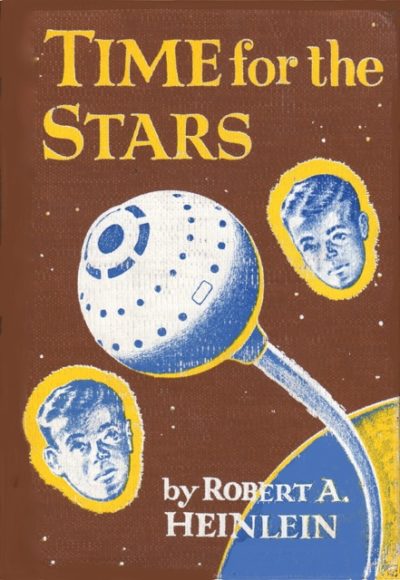

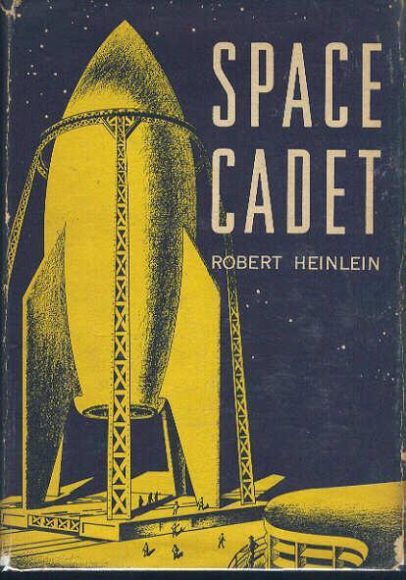

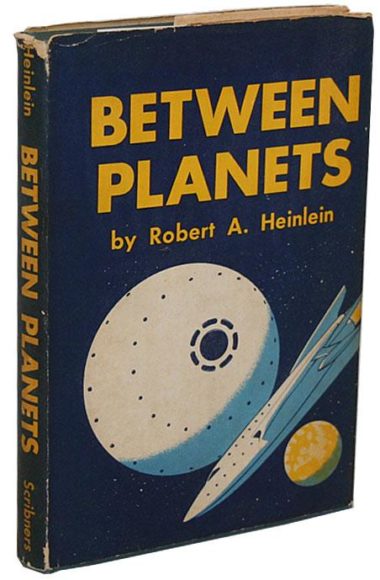

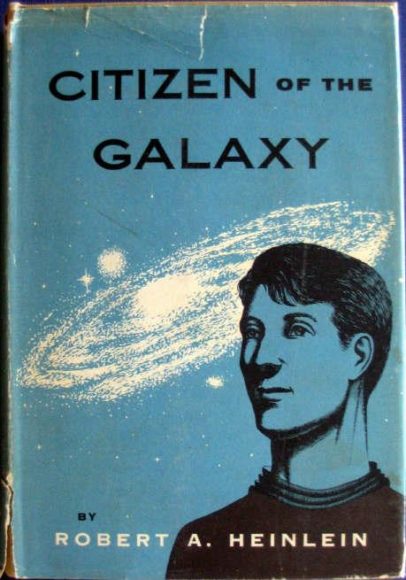

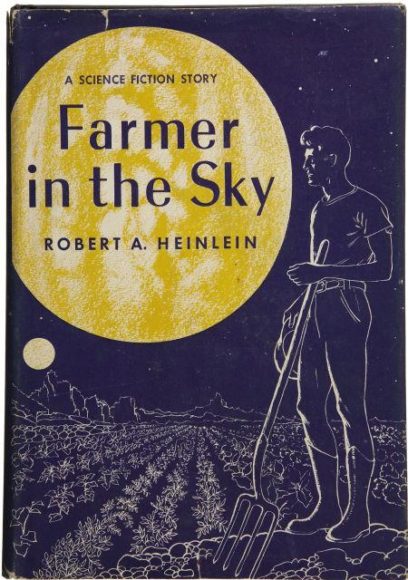

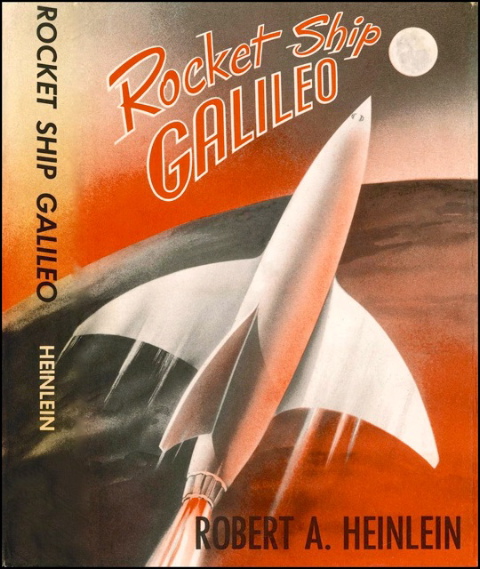

For example, I hate seeing any cover for the twelve Heinlein juveniles except those from the original publisher Charles Scribners Sons. However, I do accept the covers from the pulp digest magazines where the stories first appeared. When I started collecting pulp magazines the first thing I did was collect the mags that contained stories by Heinlein.

Thus, these are the acceptable images I have for Have Space Suit-Will Travel. By the way, Worlds Without End causes me endless memory heartache because they often use covers I don’t associate with a title. If you click on the title link above you’ll see one I particularly dislike. In fact, I dislike all the covers for Have Space Suit-Will travel but these two:

They were both done by Emsh (Ed Emshwiller). Do you also have this hangup about book covers? If so, leave a comment. I’m curious how visual memories affect other people.

Someone commented on my blog that they remember the paperback covers instead because they didn’t buy hardbacks or get science fiction from the library. I remember having several sources of science fiction. First were library books I got at school, or the Homestead Air Force Base Library or the downtown main branch of the Miami Public Library. This is where I saw all those first edition hardbacks I show off on my blog. That’s why I remember hardbacks along with paperbacks.

When I began making my own money in the 9th grade mowing lawns and having a paper route, I started going to used bookstores on my bike or buying new paperbacks off of twirling racks in drugstores. Used bookstores are where I began seeing old paperbacks and digest pulp magazines covers that have been burned into my brain. In the tenth grade, I joined the Science Fiction Book Club and began collecting hardback editions. Their covers are also etched deep in my memories. My formative mind imprinted on those covers and I’m now haunted by them. I wonder how long this bout of nostalgia will last?

Joachim Boaz has been tweeting photos of his bookshelves. Not only does this trigger nostalgia, but envy. In my lifetime I’ve owned thousands of books and magazines, but I’ve given most away. When I read the titles on Joachim’s shelves I see so many I once owned. His old paperbacks trigger so many memories. I wonder if Joachim is less nostalgic than I am because he owns all those books that I can only remember when I see a photograph.

SFFaudio also tweets and retweets images that often sets off my nostalgia. They also show a lot of interior art, as well as table-of-contents pages and images of pages to read from the past. From all the photos they tweet I can tell they also have the nostalgia flu.

Yesterday I went to the public library and went up and down the ranges that held their science fiction collection. Most of their science fiction is newer and I don’t remember those books at all. And the older books I do remember have later editions that look unfamiliar to me. Except for a few rare finds, this experienced evoked no nostalgia. It was sad. I had hoped to find books I saw on the shelves back in the 1960s, but they are long gone. I did find a third printing of the first edition of A Canticle for Leibowitz. And I found a couple early Brian Aldiss story collections from the 1960s.

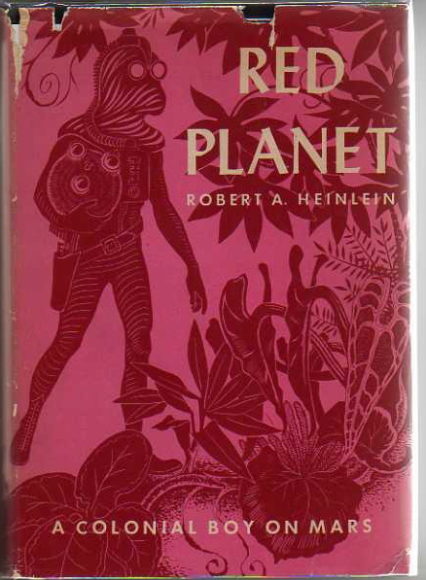

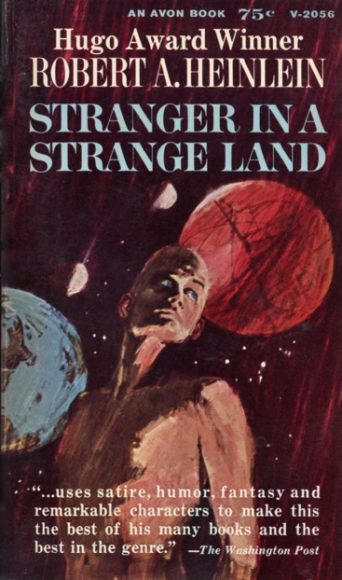

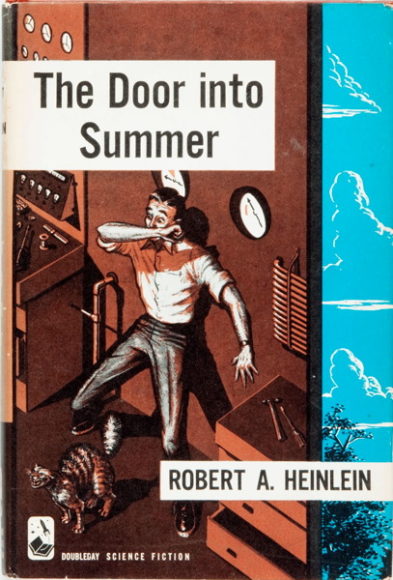

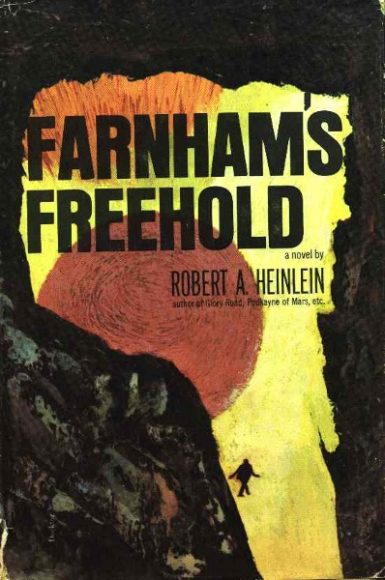

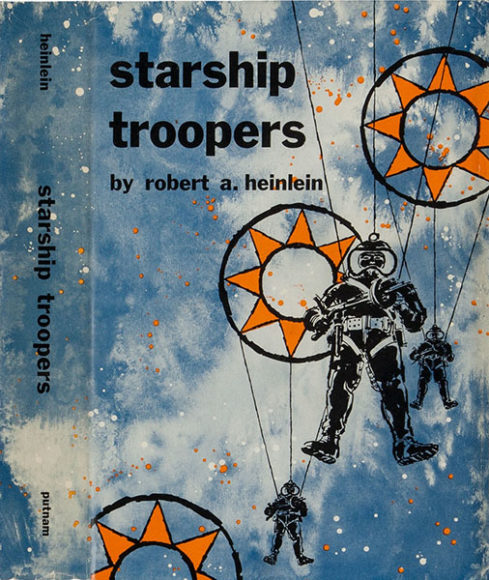

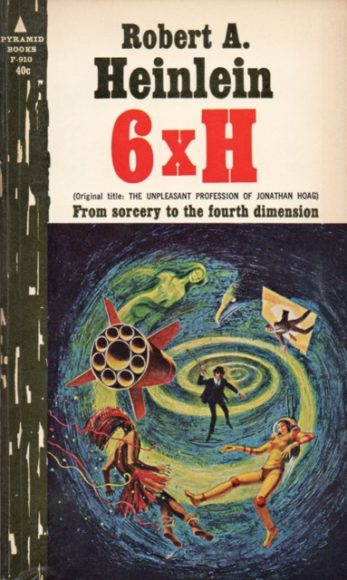

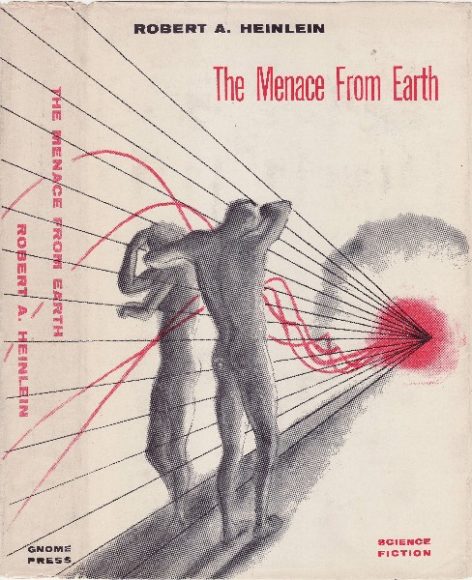

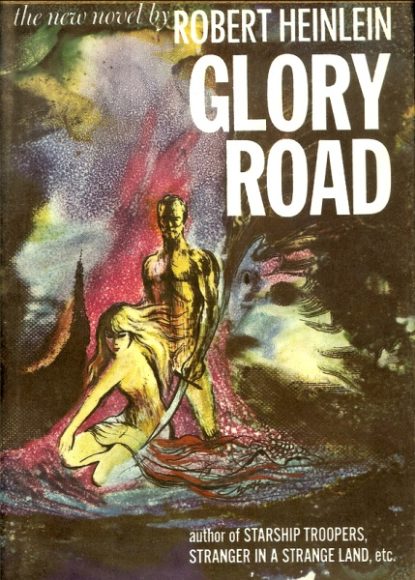

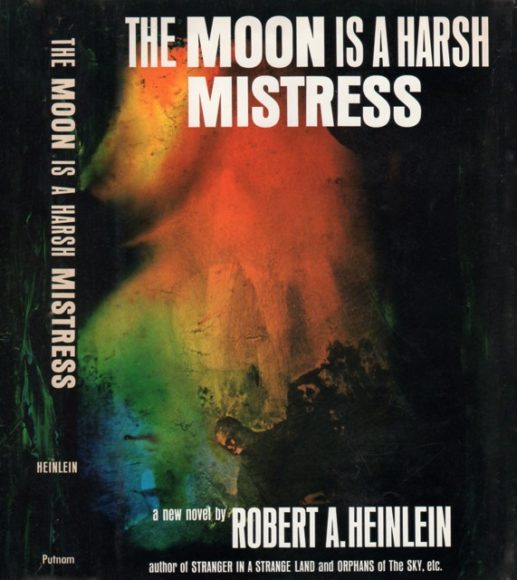

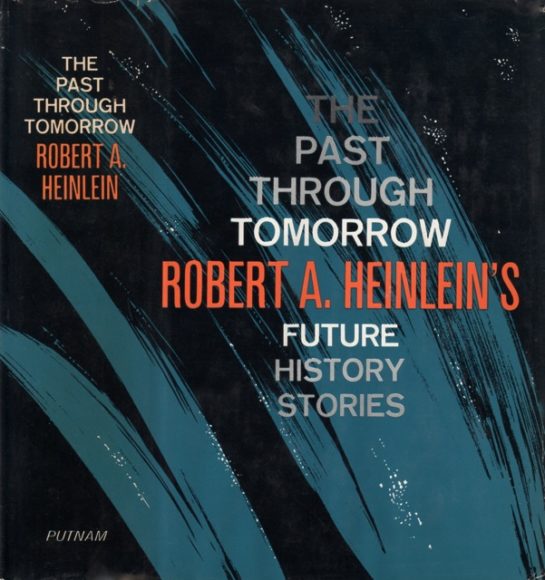

Maybe another reason my mind responds so well to photos is that I have a poor visual memory. Well, my memory for stories is also poor. Maybe what I call nostalgia is just the pleasure of recall itself. I don’t know. But for the fun of it, here’s how I remember Robert A. Heinlein. Astute observers will notice I have no nostalgia for Heinlein after 1966.

JWH

2017 Bram Stoker Award Winner!

The Horror Writers Association have announced the 2017 Bram Stoker Award winners. The winner for Superior Achievement in a Novel is:

The Horror Writers Association have announced the 2017 Bram Stoker Award winners. The winner for Superior Achievement in a Novel is:

Ararat by Christopher Golden (St. Martin’s Press)

Our congrats to Christopher and all the nominees.

- Sleeping Beauties by Stephen King and Owen King (Scribner)

- Black Mad Wheel by Josh Malerman (Ecco)

- I Wish I Was Like You by S. P. Miskowski (JournalStone)

- Ubo by Steve Rasnic Tem (Solaris)

The award presentation occurred during the annual StokerCon at the Providence Biltmore Hotel in Providence RI. See the complete list of winners in all categories at Locus.

What do you think of this result?

Full Details

Full Details