Killer NPR Top 100 Flowchart from SF Signal

Last month we posted the NPR: Top 100 Science-Fiction, Fantasy Books list to WWEnd. The list was built from over 5,000 nominations and voted upon by over 60,000 SF/F fans on NPR’s website. The resulting list is an odd one to say the least and has received mixed reviews from fans – both for the books it contains, or does not contain, and for the strange construction of the list.

Last month we posted the NPR: Top 100 Science-Fiction, Fantasy Books list to WWEnd. The list was built from over 5,000 nominations and voted upon by over 60,000 SF/F fans on NPR’s website. The resulting list is an odd one to say the least and has received mixed reviews from fans – both for the books it contains, or does not contain, and for the strange construction of the list.

The list includes entire series counted as one "novel" like the massive 33 volume Xanth Series and the 14 volume Vorkosigan Saga along with a couple incomplete series such as The Kingkiller Chronicles, so far only 2 volumes, and George R. R. Martin‘s A Song of Ice and Fire which currently, and likely for a couple years longer at least, stands at 5 books. There is also the inclusion of the Watchmen and The Sandman comics into a list of best novels to contend with too. I won’t even get into the books and authors that are missing!

Despite some strange choices and other peccadilloes, it’s been the general consensus here at WWEnd, and with many fans that we’ve talked to, that it’s a perfectly fine "fan favorite" list but not really a serious contender for a "best SF/F novels of all time" list. Compare it to a more sober and wider ranging list like Guardian’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy Novels or The ISFDB Top 100 Books to see what we mean.

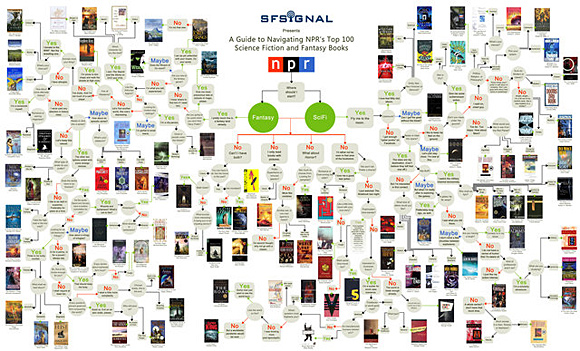

The best thing that the NPR list has going for it is the newly minted and extremely geeky awesome decision-matrix-flow-chart-info-graphic-thingy™ from SF Signal. Click the image to read the article and to see this thing it all its full size glory. I’ll wait… Back? OK, is that amazing or what? It actually makes me care about the NPR list now. This is a work of mad genius! I love following the decisions through all the gyrations and the pithy, sometimes snarky, comments along the way make it wicked good fun. I especially like the thread that leads you to Military SF that ends with "Who shall we fight? –> Everyone –> Old Man’s War." Calls in the comments section to make this into a poster have quickly been answered so you can get an 11×17 printed version for your very own. Schweet.

So what do you guys think of the NPR list and the SF Signal’s art work for it? What other lists would you like to see get this kind of treatment?

Update 10/03/11: In a successful bid to out-do themselves, the guys at SF Signal have turned their excellent flowchart into an excellent interactive guide. Now you can click through the decision matrix one step at a time until you get to a book you want to try. You can traverse up and down the line and chase down different paths like a choose you own adventure for adults! Clear proof that the SF Signal nerds are more nerdy than you.

Automata 101: Gothic Romance and the Uncanny

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. This blog will outline her experiences teaching an Honors English Composition course about created entities, beginning with the golem of Jewish legend and continuing through cyborgs, robots, androids, and artificial intelligence.

My goal for this section was to introduce the students to the concept of the uncanny and connect it to humanity’s perception of robots. I also wanted to focus on different types of texts in this section. We read short stories, articles, and essays.

We began by reading the classic “uncanny” short story: E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman,” in which a university student, Nathanael, falls in love with an automaton, Olimpia, that he believes is his professor’s daughter. Sigmund Freud used this story in his famous essay on the uncanny to explain the concept. However, we did not read Freud’s essay because it focuses more on castration anxiety than the uncanny. Instead, we read an older essay on the uncanny by Ernst Jentsch, “On the Psychology of the Uncanny (PDF),” published in 1906. This essay posits that our feelings of the uncanny stem from our inability to determine if a figure is alive or not, which is a good, basic concept for us to use in the class.

We began by reading the classic “uncanny” short story: E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman,” in which a university student, Nathanael, falls in love with an automaton, Olimpia, that he believes is his professor’s daughter. Sigmund Freud used this story in his famous essay on the uncanny to explain the concept. However, we did not read Freud’s essay because it focuses more on castration anxiety than the uncanny. Instead, we read an older essay on the uncanny by Ernst Jentsch, “On the Psychology of the Uncanny (PDF),” published in 1906. This essay posits that our feelings of the uncanny stem from our inability to determine if a figure is alive or not, which is a good, basic concept for us to use in the class.

While the reading audience sees this live/not live confusion through the character of Nathanael, another Hoffmann story “The Automata” does a better job in conveying the feeling of the uncanny for everyone. When speaking of the fortune-telling automaton, The Turk, that’s all the rage, one character confesses:

“All figures of this sort,” said Lewis, “which can scarcely be said to counterfeit humanity so much as to travesty it in mere images of living death or inanimate life are most distasteful to me. When I was a little boy, I ran away crying from a waxwork exhibition I was taken to, and even to this day I never can enter a place of the sort without a horrible, eerie, shuddery feeling.

When I see the staring, lifeless, glassy eyes of all the potentates, celebrated heroes, thieves, murderers, and so on, fixed upon me, I feel disposed to cry with Macbeth: ‘Thou hast no speculation in those eyes / Which thou dost glare.’ And I feel certain that most people experience the same feeling, though perhaps not to the same extent. For you may notice that scarcely anyone talks, except in a whisper, in waxwork museums. You hardly ever hear a loud word. But it is not reverence for the Crowned Heads and other great people that produces this universal pianissimo; it is the oppressive sense of being in the presence of something unnatural and gruesome; and what I detest most of all is the mechanical imitation of human motions.”

I wanted to counter these Hoffmann stories with an activity that allowed the students to experience a bit of the uncanny rather than search for it in Hoffmann’s dense, gothic prose. I gave them the assignment to watch several videos of robots and write a response that explained why they found a certain one the most uncanny. I sent them to this Creepiest Robots web page at the Huffington Post. (I had them watch the videos numbered 1, 17, 22, and 23, although plenty of them are uncanny.)

While each one of the four robots had one student choose it as the most uncanny, numbers 1 and 17 were the robots that the students wrote about the most. The class discussion was lively as each student defended his or her choice and asked the other students questions about theirs.

Now that the students had a better grasp of the uncanny, we read “The Uncanny Valley” (1970) by roboticist Masahiro Mori. He argues that robots, androids, and cyborgs that are too human-like in appearance fall into an uncanny valley in human perception. He recommends that the creators of these machines avoid making them resemble people too much. You can see his famous graph that depicts the uncanny valley and an interesting slideshow at this blog.

We followed “The Uncanny Valley” with an article from The New Scientist, “What Puts the Creepy into Robot Crawlies? (PDF)” (2007), by Jim Giles. This article is valuable because it summarizes Mori’s argument and then presents newer research. It explains that researchers, Thierry Chaminade and Ayse Saygin of University College London, use brain scans to observe the parts of subjects’ brains that are activated when they see a human, a humanoid robot, and a mechanical robot performing similar human actions, such as picking up a cup. The researchers believe the feeling of the uncanny can be found in the specific areas of the subjects’ brains that are activated only when the humanoid robot is observed.

We followed “The Uncanny Valley” with an article from The New Scientist, “What Puts the Creepy into Robot Crawlies? (PDF)” (2007), by Jim Giles. This article is valuable because it summarizes Mori’s argument and then presents newer research. It explains that researchers, Thierry Chaminade and Ayse Saygin of University College London, use brain scans to observe the parts of subjects’ brains that are activated when they see a human, a humanoid robot, and a mechanical robot performing similar human actions, such as picking up a cup. The researchers believe the feeling of the uncanny can be found in the specific areas of the subjects’ brains that are activated only when the humanoid robot is observed.

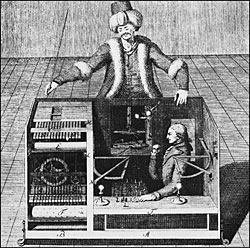

The last texts in this section make an interesting pair: Edgar Allan Poe’s 1836 essay, “Maelzel’s Chess Player” and F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre’s story, “The Clockwork Horror,” that fictionalizes Poe’s essay. In “Maelzel’s Chess Player,” Poe, as a writer for Richmond’s Southern Literary Messenger, investigates a traveling automaton show, featuring the Turk, which played chess in exhibition matches. His essay debunks the Turk and explains how a human is hidden in the elaborate box that houses the false automaton. My purpose in assigning this essay was to expose the students to the idea that robot-like automata were not uncommon exhibitions at the time that Hoffmann and his contemporaries were writing about them in fiction.

In fact, the automaton that Poe saw in 1836 was probably Hoffmann’s inspiration for his Turkish fortune-teller. The same machine had been touring Europe and America since the late 1700s. Jane Irwin has created a fabulous web comic about the history of the Turk, Clockwork Game: The Illustrious Career of a Chess-Playing Automaton. I’ve just started reading it. Too bad I didn’t know about the comic when I was teaching this section. I’ve put it on the course website.

Poe’s essay tells his readers that he commandeers the audience after the Turk’s game and explains how the box contains a hidden chess player and uses magician’s tricks to hide the player during Maezel’s lengthy exposure of the cabinet. Here we glimpse the writer who will create C. Auguste Dupin and his stories of ratiocination. Since Poe’s prose is dense and a bit hard to get through, I also assigned MacIntyre’s story to give the students an account of Poe’s reasoning in a more accessible form. MacIntyre did some research for this horror story and was able to fill in some blanks that Poe left out.

Poe’s essay tells his readers that he commandeers the audience after the Turk’s game and explains how the box contains a hidden chess player and uses magician’s tricks to hide the player during Maezel’s lengthy exposure of the cabinet. Here we glimpse the writer who will create C. Auguste Dupin and his stories of ratiocination. Since Poe’s prose is dense and a bit hard to get through, I also assigned MacIntyre’s story to give the students an account of Poe’s reasoning in a more accessible form. MacIntyre did some research for this horror story and was able to fill in some blanks that Poe left out.

I’m happy with the way this section turned out. The students read several different types of texts–from difficult nineteenth-century authors to an article from a popular science magazine–examined the uncanny from different perspectives, and gained some historical context. They’ll get more history in the next section when we begin with early-twentieth-century robots in R. U. R. and Metropolis.

Philip K. Dickathon: Time Out of Joint

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

Throughout the 1950’s, Philip K. Dick continued to write mainstream novels involving working class characters and realistic situations. His agents were never able to place any of these titles with publishers, at least not until several years after Dick’s death when the Dickian industry began in earnest and publishers were scrounging for new material. Dick sometimes disparaged his sf output, but he continued to have faith in these realist novels into the 1960’s.

Throughout the 1950’s, Philip K. Dick continued to write mainstream novels involving working class characters and realistic situations. His agents were never able to place any of these titles with publishers, at least not until several years after Dick’s death when the Dickian industry began in earnest and publishers were scrounging for new material. Dick sometimes disparaged his sf output, but he continued to have faith in these realist novels into the 1960’s.

Time out of Joint, published in 1959, is a science fiction story that reads, for much of the time, as one of Dick’s mainstream efforts. The characters are middle management types, one manages the produce department of a local grocery store, another works for the water department. They live in a new suburb of modest homes and are somewhat civically active. One couple, Vic and Margo, share their home with Margo’s brother, Raigle, a war veteran who makes a comfortable living by answering a daily newspaper quiz, Where Will the Little Green Man Land Next. He is always right and has become something of a celebrity.

The first odd moment arrives when Vic looks through a newly arrived brochure from the Book-of-the-Month Club and wonders who Harriet Beecher Stowe might be. It’s possible he wouldn’t know, but later Raigle sees a layout in Life Magazine and marvels that the featured starlet’s breasts can maintain the tilt they have in the photographs. Since this is a Philip K. Dick novel, all three characters analyze the breasts in some detail but then also wonder among themselves just who Marilyn Monroe could be that she would merit so much attention.

The next day, while Raigle contemplates adultery with the neighbor’s wife, he takes her to the municipal swimming pool, and when he goes to the refreshment stand for cokes, the stand and its manager fade from sight leaving behind only a piece of paper with the printed words SOFT-DRINK STAND. Raigle puts the note into a box he keeps in his pocket where similar messages read DOOR, FACTORY BUILDING, BOWL OF FLOWERS.

We are now in Dickian territory, where few people are who they claim to be, and a trip past the city limits is a trip to another world. Dick earns his standing as the connoisseur of American paranoia with this one. Early on Raigle has the insight that he may be the most important person in the world. He’s no dummy.

Vonnegut Unbanned (sort of)

We have an update on that school board in Missouri that banned Slaughterhouse-Five from a high school libary. In case you missed it, the Republic school district had banned two books (including Vonnegut‘s masterpiece) after a citizen (who did not have children in the district) complained that they contradicted his interpretation of the Bible. Since then, the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library has offered to give away 150 copies of Slaughterhouse-Five, and the ACLU has expressed interest in litigating the policy.

We have an update on that school board in Missouri that banned Slaughterhouse-Five from a high school libary. In case you missed it, the Republic school district had banned two books (including Vonnegut‘s masterpiece) after a citizen (who did not have children in the district) complained that they contradicted his interpretation of the Bible. Since then, the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library has offered to give away 150 copies of Slaughterhouse-Five, and the ACLU has expressed interest in litigating the policy.

After all of the blinding national attention, the board reconsidered its position and is allowing the books to return to library shelves. It isn’t a complete victory for free speech advocates, as they will only allow parents to check out the books on behalf of their children. This may mean that students may still read the book in the reading room, as well (this has not yet been tested). What do you think of this compromise?

All of this comes just in the nick of time for Banned Books Week, which starts this Saturday. In celebration, we suggest that you get to work on the Banned Science Fiction & Fantasy Books list that we introduced in July. You can kick things off by reading any of Vonnegut’s banned books for only $3.99 on Kindle.

By the way, if you know of a banned SF/F book that has not made our list, please let us know in the comments. We’ll add it right away.

Philip K. Dickathon: The World Jones Made

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

Philip K. Dick published The World Jones Made in 1956 and didn’t give "life as we know it" much time. A devastating world war breaks out in the 1970’s, but humankind proves remarkably resilient. By the mid 1990’s, when the story begins, we are already zipping around town in airborne taxis and traveling cross country in the matter of an hour or so. You may live in Detroit but you party in San Francisco. "Relativity" is the accepted philosophy of the day, and I found it one of Dick’s vaguer concepts. People can not only do most anything they want, but they must let others do so as well, and they cannot, under any circumstances, express a belief in anything. This live and let live code must be enforced by an elaborate security police force, and Cussick, the central character, is on the force.

Philip K. Dick published The World Jones Made in 1956 and didn’t give "life as we know it" much time. A devastating world war breaks out in the 1970’s, but humankind proves remarkably resilient. By the mid 1990’s, when the story begins, we are already zipping around town in airborne taxis and traveling cross country in the matter of an hour or so. You may live in Detroit but you party in San Francisco. "Relativity" is the accepted philosophy of the day, and I found it one of Dick’s vaguer concepts. People can not only do most anything they want, but they must let others do so as well, and they cannot, under any circumstances, express a belief in anything. This live and let live code must be enforced by an elaborate security police force, and Cussick, the central character, is on the force.

Jones threatens this world because he is a prophet, able to see into the future for up to one year. This means that the future is known, it is a sure thing, and so the Relativity world will fall apart. The mob longs for Jones’s message and forms a devoted following that transforms into a worldwide movement. He can’t be stopped because he already knows every move that will be made against him. Cussick’s gorgeous Scandinavian wife aligns herself with the Jones movement and becomes a senior officer in the organization. There is a subplot concerning human mutants specially bred to survive on Venus, and an inconvenient but not very dangerous invasion of giant space amoebas that the Jones followers raucously destroy.

All of this does not make into a very coherent novel, and, for as nutty as much of it is, The World Jones Made is a little downbeat for Dick. The characters, other than Jones, are exhausted and justifiably pessimistic, caught up in defending a world order they know is doomed and which they no longer really believe in. No wonder they go to night clubs and make concoctions of heroin and marijuana their first drink of the night.

Automata 101: Frankenstein’s Monster as Golem

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. This blog will outline her experiences teaching an Honors English Composition course about created entities, beginning with the golem of Jewish legend and continuing through cyborgs, robots, androids, and artificial intelligence.

Before we started reading Frankenstein, I wanted to introduce the students to many of the concepts we would work with this semester. For the first class, they listened to a children’s story, The Golem of Prague, and read a different account of it by Jacob Grimm. They also read Jorges Luis Borges’ poem “The Golem” and Biblical and Talmudic verses about the creation. Here’s a translation of Borges’ poem, though we used a different translation from Borges: Selected Poems in class.

Before we started reading Frankenstein, I wanted to introduce the students to many of the concepts we would work with this semester. For the first class, they listened to a children’s story, The Golem of Prague, and read a different account of it by Jacob Grimm. They also read Jorges Luis Borges’ poem “The Golem” and Biblical and Talmudic verses about the creation. Here’s a translation of Borges’ poem, though we used a different translation from Borges: Selected Poems in class.

These varied texts enabled us to list some parameters for the semester’s discussion on the board. The ones that I remember most clearly are:

- creation – magical, divine, scientific: where do they overlap? how can we tell?

- man playing God, creating the other, creating new Adams: what is the responsibility of the maker?

- importance of material in creation: clay, mud, dust, dirt. What other materials will we see?

- communication: why can some golems speak, others not? how will communication or lack of it figure in these texts?

We spent a lot of time working on the complex meaning of Borges’ last stanza:

“In that hour of dread and blurred light,

his eyes lingered on his Golem.

Who will tell us, what did God feel,

looking upon His rabbi in Prague?”

The class focused quickly on the lines’ various interpretations: Does God feel that He failed when He created man? Has He always felt this way? Did the rabbi’s making the Golem cause this feeling? Does this poem pose creation as positive and human or instead ambition as negative and taboo?

All of this was a perfect set-up for Frankenstein, which we began the next class. Only about four of the seventeen students had read the book before, so much of our first discussion dealt with their surprise that the creature is not called Frankenstein and he’s not a green giant with bolts in his neck. I told the students that that particular image emerged from James Whale’s 1931 movie that starred Boris Karloff as the creature; however I did not know much more. After class, I found a great website that discusses Universal’s make-up artist, Jack Pierce’s, philosophy in designing the monster’s overall look. I posted the link on the course website, and we discussed it a bit in the next class.

All of this was a perfect set-up for Frankenstein, which we began the next class. Only about four of the seventeen students had read the book before, so much of our first discussion dealt with their surprise that the creature is not called Frankenstein and he’s not a green giant with bolts in his neck. I told the students that that particular image emerged from James Whale’s 1931 movie that starred Boris Karloff as the creature; however I did not know much more. After class, I found a great website that discusses Universal’s make-up artist, Jack Pierce’s, philosophy in designing the monster’s overall look. I posted the link on the course website, and we discussed it a bit in the next class.

The students were also surprised that there’s so little discussion of how Victor Frankenstein made the creature. We discussed how this is often considered the first science fiction novel even though it contains very little science. (The WWEnd forum has a good discussion about early science fiction.) We spent some time differentiating the kinds of science that does appear in the book. Interestingly, Shelley’s introduction provides some details of her vision concerning Frankenstein’s use of engines and galvanism in the animation of the creature. Those details are glossed over in the novel. Nevertheless, Shelley very carefully poses the new Enlightenment sciences of chemistry and anatomy against medieval and Renaissance notions of alchemy. Of course, the irony is that the combination of both types of knowledge allows Frankenstein to do the unthinkable and create life.

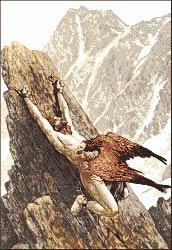

We decided that Shelley’s paucity of science indicates that she’s not really interested in the “how” but in what happens after the creation. I focused them on the novel’s subtitle, The Modern Prometheus, as a way to discuss the book’s role as a cautionary tale against scientific overreaching. Most of them knew that Prometheus brought fire to man in Greek mythology. However, they did not know that in some myths he created mankind from clay and water; this, of course, brought us back to the golem stories. Some remembered that Prometheus’ punishment was to have his internal organs eaten by vultures each day and then they would regenerate at night so that they could be eaten again in an eternal cycle of punishment. We compared this physical punishment to Victor Frankenstein’s mental anguish. I was proud that several of them made the connection between Frankenstein and his interlocutor, Captain Walton, as men whose scientific curiosity could lead to their anguish and destruction.

We decided that Shelley’s paucity of science indicates that she’s not really interested in the “how” but in what happens after the creation. I focused them on the novel’s subtitle, The Modern Prometheus, as a way to discuss the book’s role as a cautionary tale against scientific overreaching. Most of them knew that Prometheus brought fire to man in Greek mythology. However, they did not know that in some myths he created mankind from clay and water; this, of course, brought us back to the golem stories. Some remembered that Prometheus’ punishment was to have his internal organs eaten by vultures each day and then they would regenerate at night so that they could be eaten again in an eternal cycle of punishment. We compared this physical punishment to Victor Frankenstein’s mental anguish. I was proud that several of them made the connection between Frankenstein and his interlocutor, Captain Walton, as men whose scientific curiosity could lead to their anguish and destruction.

The paragraphs above represent only a fraction of issues that arose in class: we also discussed the Edenic/pastoral overtones of the creature’s desires, the role of the Industrial Revolution in Shelley’s work, and Frankenstein as a romantic hero.

I think Frankenstein was a good place to begin our discussion. The novel makes a good foundation for future discussions about the role of responsibility in scientific discovery. The students seemed very grounded in their understanding of the issues we will be exploring. I’m glad they gained that confidence because next up is E.T.A. Hoffman, who is always a bit disjointed and perplexing.

@WWEnd I wonder, will Dr. Knight get to Marge Piercy's He, She & It (Body of Glass) in this course? I hope so…

— Margo-Lea Hurwicz (@MangoHeroics) June 13, 2013

The Inner Galaxy

Loren Eiseley (1907-1977) was not a science fiction writer, but he was a science writer, and a poet. A friend of mine recently shared some excerpts from Eiseley’s essay collection The Star Thrower, and I enjoyed them enough that I wanted to post one here.

Loren Eiseley (1907-1977) was not a science fiction writer, but he was a science writer, and a poet. A friend of mine recently shared some excerpts from Eiseley’s essay collection The Star Thrower, and I enjoyed them enough that I wanted to post one here.

I remain oppressed by the thought that the venture into space is meaningless unless it coincides with a certain interior expansion, an ever-growing universe within, to correspond with the far flight of the galaxies our telescopes follow from without.

Upon that desolate peak my mind had finally turned inward. It is from that domain, that inner sky, that I choose to speak—a world of dreams, of light and darkness that we will never escape, even on the far edge of Arcturus. The inward skies of man will accompany him across any void upon which he ventures and will be with him to the end of time. There is just one way in which that inward world differs from outer space. It can be more volatile and mobile, more terrible and impoverished, yet withal more ennobling in its self-consciousness, than the universe that gave it birth. To the educators of this revolutionary generation, the transformations we may induce in that inner sky loom in at least equal importance with the work of those whose goals are set beyond the orbit of the moon.

(From the essay “The Inner Galaxy.”)

Philip K. Dickathon: The Man Who Japed

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

I was going to say that The Man Who Japed was for Philip K. Dick completists only, but then I read that in the mid 60’s he considered it the best thing he had written to date. And this was after Man in the High Castle had won the Hugo Award.

I was going to say that The Man Who Japed was for Philip K. Dick completists only, but then I read that in the mid 60’s he considered it the best thing he had written to date. And this was after Man in the High Castle had won the Hugo Award.

I don’t know why he was so fond of it. The Man Who Japed was originally half of an Ace Double, so it could pass as a novella. It is also just one of about five book-length works Dick wrote or put under copyright in 1956. Familiar PKD elements are all in place: a postwar dystopian future, a lone hero going against the code, incredibly fast pacing, digs at psychiatry, a brief trip to another planet. This is a moral world where the morality is enforced by neighborhood watch societies headed by middle-aged women in floral print dresses. (Such beings seem to be a particular horror to PKD. They show up in Eye in the Sky as well.) The ladies get their information from "the juveniles," two-foot-long mechanical centipedes charged with keeping a watch on things. Alan Purcell is part of this system. He works in a form of advertising that broadcasts campaigns with moral lessons that are good for the populace. During the course of the book he falls very afoul of the system and plots to overthrow it.

Satire and action here are good, but Dick’s most prescient insights have to do with real estate. In the 22nd century people with tiny apartments close to the center of town live in fear of code violations that will exile them to what I suppose are tenements or something equally unpleasant further out.

Automata 101: Introduction

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. This blog will outline her experiences teaching an Honors English Composition course about created entities, beginning with the golem of Jewish legend and continuing through cyborgs, robots, androids, and artificial intelligence.

This semester I’m teaching a course that examines the relationship between humans and created beings. (I wish I had a catchier name, but "created beings" seems to cover the various organic, mechanical and digital creatures that inhabit my syllabus.) Since the Worlds Without End site, especially the sub-genre lists, was instrumental in my syllabus development, I decided to share my reading list in the forum. From there, Dave, Rico and I decided that it might be interesting if I blogged about my experiences and those of my students. This first blog will serve as an overview while the subsequent ones will focus on specific texts or issues.

This semester I’m teaching a course that examines the relationship between humans and created beings. (I wish I had a catchier name, but "created beings" seems to cover the various organic, mechanical and digital creatures that inhabit my syllabus.) Since the Worlds Without End site, especially the sub-genre lists, was instrumental in my syllabus development, I decided to share my reading list in the forum. From there, Dave, Rico and I decided that it might be interesting if I blogged about my experiences and those of my students. This first blog will serve as an overview while the subsequent ones will focus on specific texts or issues.

First, a bit about the class: Coker College offers one section of Honors Composition each semester. The students are all good readers and writers as well as enthusiastic and industrious — a pleasure to teach. Most of them are first-semester, first-year students. Often it is a challenge to find literary texts that these students have not studied in their AP or Honors English classes or read on their own, so I always try to pick out-of-the-mainstream texts that most of them have not read or often have not heard about.

This year my inspiration for the course is the keynote speaker for the Coker College Undergraduate Humanities Conference in February. He is J. Andrew Brown, author of Cyborgs in Latin America. (You can download a free copy of the book here.) The conference co-founder, Dr. Mac Williams, is an Assistant Professor of Spanish, and he informed me that there are many innovative Hispanophone novels that explore the relationships between technology and humanity, posthumanity, and the like. I decided that this would be a great way to tie my recreational reading with a class whose goal would be to have student papers worthy for presentation at the conference in February. This type of presentation will be a new experience for freshman students who usually don’t have such opportunities.

In the class, we will read novels, short stories, essays, and articles from social science journals and popular magazines. We will also watch movies. I will talk about the secondary works as I blog about each section, but in this overview it is my intention to discuss each section and the primary works in it.

In Frankenstein’s Monster as Golem, we will apply several texts about the Golem and creation to Mary Shelley‘s Frankenstein. The primary questions we will explore in this section are: Why does Victor Frankenstein try to create a being? What is his responsibility to the being once created? What is at stake when one pushes the boundaries of science and knowledge? Can scientists/inventors ever "get it right" if they are afraid to "get it wrong"?

In Frankenstein’s Monster as Golem, we will apply several texts about the Golem and creation to Mary Shelley‘s Frankenstein. The primary questions we will explore in this section are: Why does Victor Frankenstein try to create a being? What is his responsibility to the being once created? What is at stake when one pushes the boundaries of science and knowledge? Can scientists/inventors ever "get it right" if they are afraid to "get it wrong"?

In Gothic Romance and the Uncanny, we will read several short texts — E. T. A. Hoffmann‘s stories, "The Sandman" and "The Automata," Edgar Allan Poe‘s essay, "Maelzel’s Chess Player," and F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre‘s "The Clockwork Horror," which is a retelling of Poe’s essay. My goal in this section is to introduce the students to the concept of the uncanny. The texts all focus on 19th century "robots," or clockwork beings, which will allow us to test the boundaries of what makes these machines uncanny.

In Gothic Romance and the Uncanny, we will read several short texts — E. T. A. Hoffmann‘s stories, "The Sandman" and "The Automata," Edgar Allan Poe‘s essay, "Maelzel’s Chess Player," and F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre‘s "The Clockwork Horror," which is a retelling of Poe’s essay. My goal in this section is to introduce the students to the concept of the uncanny. The texts all focus on 19th century "robots," or clockwork beings, which will allow us to test the boundaries of what makes these machines uncanny.

In Robots and the Mechanical Age, we will read several of Isaac Asimov‘s stories and essays from Robot Visions and Karel Capek‘s play R. U. R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). We will also watch clips from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. I hope that the movie will help the students understand the context of R.U.R, which is a very powerful piece but a bit didactic in its tone. This section explores what happens when mechanical creatures learn, evolve and start making decisions. We will not ignore the Marxist overtones, but we will also look at these robots as robots and not just as symbols the proletariat. We will examine the texts as explorations of human fears and desires concerning robots.

In Robots and the Mechanical Age, we will read several of Isaac Asimov‘s stories and essays from Robot Visions and Karel Capek‘s play R. U. R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). We will also watch clips from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. I hope that the movie will help the students understand the context of R.U.R, which is a very powerful piece but a bit didactic in its tone. This section explores what happens when mechanical creatures learn, evolve and start making decisions. We will not ignore the Marxist overtones, but we will also look at these robots as robots and not just as symbols the proletariat. We will examine the texts as explorations of human fears and desires concerning robots.

In Cyborgs and Androids, we will focus on the two most intriguing novels of the bunch, Marge Piercy‘s He, She and It and Philip K. Dick‘s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? We will also watch Blade Runner. Unfortunately, this is the section that I have thought the least about. I know we will do some work on defining terms, robot, cyborg, and android and discuss their slipperiness in science fiction writing. We will also continue our discussion that we begun in the previous section about created beings and free will.

In Cyborgs and Androids, we will focus on the two most intriguing novels of the bunch, Marge Piercy‘s He, She and It and Philip K. Dick‘s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? We will also watch Blade Runner. Unfortunately, this is the section that I have thought the least about. I know we will do some work on defining terms, robot, cyborg, and android and discuss their slipperiness in science fiction writing. We will also continue our discussion that we begun in the previous section about created beings and free will.

In the final section, The Artist as Golem Maker, we will read Michael Chabon‘s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. The Golem plays a small role in this novel, but this exploration of the origin of comics provides an interesting way into discussing modern and postmodern ideas of creation. I hope that by November many of the ideas we’ve discussed will represent themselves in the guise of the superheroes.

In the final section, The Artist as Golem Maker, we will read Michael Chabon‘s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. The Golem plays a small role in this novel, but this exploration of the origin of comics provides an interesting way into discussing modern and postmodern ideas of creation. I hope that by November many of the ideas we’ve discussed will represent themselves in the guise of the superheroes.

I hope this introduction has piqued your interest and you will send me feedback as I document the course. So far the students have been extremely enthusiastic and we’ve had some great discussions – more on that in my next blog.

All Hallow’s Read

Labor Day has come and gone, and you know what that means. Well, here in Texas, it means no more long strings of 100+° days. For the rest of you, it could mean the start of a new school year, locking up your favorite white sweater, and stocking up for Halloween. Normally, I don’t think about that last thing until, oh, around noon on October 31st. This year, however, I’ll be scoping the used book stores about once per week in preparation for All Hallow’s Read, a new tradition that Neil Gaiman suggested so late last year that I wasn’t prepared to do anything about it. Well, this year, I’m going to be ready.

You can’t just give out any book, of course. It has to be scary. Because I want to promote the best in science fiction and fantasy, I also want them to be WWEnd books. After all, I have my standards. So, here’s my strategy: I made a list of the scariest novels in the WWEnd database for this week’s blog entry. Then, I’m taking my smart phone to the local Half Price Books, where I will pull up this very blog entry. See how organized I am? I’m hoping to get dozens of copies of the following books:

This one is a no-brainer. Not only does it appear on virtually every classic SF list (including Classics of SF, Locus, Guardian, and NPR), it has long been held to be the first science fiction novel ever (Brian Aldiss makes the argument in Billion Year Spree). It’s also worth noting that the first science fiction novelist was a woman, making Frankenstein the oldest book on the SF Mistressworks list. The novel is, perhaps, most scary to government officials, as it was variously banned in places like South Africa and (gulp) Texas.

Dracula, by Bram Stoker

Dracula, by Bram Stoker

It wasn’t the first (or even the third) vampire novel ever written, but it is, of course, the most renowned. The Guardian said that the book "spawned fiction’s most lucrative entertainment industry," but we are more impressed by its literary chops. The critics of the day favorably compared Dracula to Shelly, Emily Bronte and even the great Edgar Allan Poe. Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was impressed. Your trick-or-treaters are the best testament to the novel’s greatness, as Dracula is arguably the most popular Halloween costume — ever.

The Day of the Triffids, by John Wyndam

The Day of the Triffids, by John Wyndam

Unless you are a fan of the old black and white B movies, you probably associated man-eating plants with Little Shop of Horrors. But before Audrey 2 there were Triffids, horrifying venomous carnivores that began to prey on humans right after a meteor shower renders virtually all humans blind. That’s double the horror! At one point, the seemingly intelligent plants figure out how to herd sightless humans into groups, to, you know, maximize the carnage. The Day of the Triffids is a must read according to the Guardian and David Pringle. It also made the Classics of SF list.

Other novels I might give out include The Midwich Cuckoos (John Wyndam, again), The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Robert Louis Stephenson, Shadowland by Peter Straub, and anything by Stephen King (including his BFS award winning novel, It) or Clive Barker. For more ideas, check out the Dark Fantasy sub-genre list… and, please, tell us in the comments section what books you are going to give out.

Full Details

Full Details