GMRC Review: I, Robot by Isaac Asimov

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his fifth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his fifth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

For my fifth Grand Master reading challenge, this project may well be the only one at Random Comments that runs on schedule, I decided to read something by Isaac Asimov. Several of his novels feature prominently on all kinds of recommended reading lists and he is certainly one of the genre’s towering figures. I read his Foundation novels (the original trilogy) a while ago and I can’t say I was overly impressed. Asimov didn’t lack ideas but his prose is barely serviceable and he has the tendency to explain everything in great detail to his readers. Perhaps I should have picked something from later in his career but I, Robot (1950) is such an iconic work in the genre that I felt I should give it a go. Much to my surprise, I liked this book better than the Foundation novels. Not that the flaws in Asimov’s writing are absent in this novel, but the quality of the stories is more consistent and on the whole, I though them more entertaining as well.

I, Robot has been described as a fix-up novel or a short fiction collection. I think of it as the former but it is certainly true that most of the text appeared in the shape of various short stories between 1940 and 1950 in a Super Science Fiction Stories and of course John W. Campbell‘s Astounding Science Fiction, to whom the book is dedicated. Asimov has connected the stories with bits of interviews with Dr. Susan Calvin, a robotpsychologist working for U.S. Robots and Mechanical Men, Inc., as she is looking back on her long career in the field. She is not always the main character, or even a character, but she does provide just enough context to put the stories into a general future history. Asimov does this in his usual efficient way, not wasting a word more on it than absolutely necessary. I understand Asimov changed some of the details in the stories to make them more consistent. He is certainly making the most of repackaging these short stories with minimal effort here.

Being written in the 1940s, most or the novel is pretty badly dated and some of Asimov’s depictions of the future will seem decidedly strange to new readers. We have caught up with the start of the series now. I, Robot starts in 1996, with the story Robbie (1940), about a primitive robot and playmate of the eight year old Gloria. The girl treats the robot like she would a human friend and this makes her mother uneasy. Robbie wil have to go. Asimov uses the story to outline the resistance against artificial intelligence, the fear of superior robots replacing human beings. First in the work space and later completely. It is an introduction to his famous three laws of robotics, which he will name in the second story Runaround (1942).

"We have: One, a robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm."

"Right!"

"Two," continued Powell, "a robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law."

"Right!"

"And three, a robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws."

— Powell and Donovan discussing the Three Laws of Robotics – Runaround

Runaround, set in 2015, introduces the field testers Powell and Donovan and is a story in which Asimov examines the conflicts that may arise from these three laws. The laws are the kind of logic that Asimov seemed to have liked, simple, elegantly formulated and its intent easily understood. He was smart enough to see they are by no means flawless though. Most of the stories contain situations in which some conflict between these laws makes the robots behave unexpectedly or cause them to be caught in a loop, often jeopardizing the project they are working on or the lives of the unfortunate humans in their company. In Runaround it happens in the supremely hostile environment on Mercury, which shows just how little we knew about conditions on the planet in 1940. It gives Asimov plenty of room to speculate though.

Some six months after events in Runaround Donovan encounter a different sort of problem. In Reason (1941), which I consider to be one of the strongest stories, Asimov takes a more philosophical tone when our field testers are stuck with a robot who will not accept the (in its opinion) contrived and unnecessarily complicated explanation for its existence. A case of Occam’s razor gone blunt I suppose. This story contains the most memorable quote in the book if you appreciate sarcasm.

"I have spent these last two days in concentrated introspection", said Cutie, "and the results have been most interesting. I began at the one sure assumption I felt permitted to make. I, myself exist, because I think…"

Powell groaned, "Oh Jupiter, a robot Decartes!"

— QT-1 discussing its own existence.

Cutie retreats from reality along the same lines as a human being might do in the end by resorting to religion, shutting out the need for an explanation. It is one of several instances where robotpsychology runs parallel to human psychology. Something even Susan Calvin reluctantly admits later on in the book.

In Catch That Rabit (1944) robot behaviour shows some parallels to buggy software as well. It sees our field testers use drastic measures to get the robot back under control. Asimov spends a lot of the later part of the story lecturing (disguised as a conversation between Powell and Donovan). I can’t say I particularly liked it. Liar! (1941) is more interesting. Set in 2121, it deals with a robot that can read minds. The conflict arises when it receives one set of instructions verbally, that don’t correspond with the real desires of the person giving the instructions. Calvin’s behaviour in this story will no doubt make some readers groan but the concept is a strong one.

By the time of Little Lost Robot (1947), robots have become quite advanced and exploration of the solar system is well under way. In 2029, one such space program employs robots with a slightly altered set of robotic laws, enabling them to ignore a human being putting themselves in danger. If the mere existence of such a robot was to become public knowledge on earth, the political consequences would be dire. When one of the robots is lost, the people who run the project are in deep trouble. Calvin is called upon to find it. The three laws of robotics can be quite a restriction I suppose, so the temptation to do away with them is clear. Asimov presents a perfectly reasonable argument for doing so in this story. It might have worked better if there had been more of an element of danger in the story though. The missing robot is still unable to actively do harm. Personally I wouldn’t have been particularly worried to have it around.

By the time of Little Lost Robot (1947), robots have become quite advanced and exploration of the solar system is well under way. In 2029, one such space program employs robots with a slightly altered set of robotic laws, enabling them to ignore a human being putting themselves in danger. If the mere existence of such a robot was to become public knowledge on earth, the political consequences would be dire. When one of the robots is lost, the people who run the project are in deep trouble. Calvin is called upon to find it. The three laws of robotics can be quite a restriction I suppose, so the temptation to do away with them is clear. Asimov presents a perfectly reasonable argument for doing so in this story. It might have worked better if there had been more of an element of danger in the story though. The missing robot is still unable to actively do harm. Personally I wouldn’t have been particularly worried to have it around.

In Escape! (1945), positronic brains have become so advanced they are capable of calculations comparable of those of a super computer. The Brain, as this robot is called, is set to the task of creating the means for interstellar travel, a problem that has already cracked a competing robot. Calvin is aware that there is a conflict with the three laws but doesn’t know where. The company tries to avoid the problem by feeding The Brain the information is small sections. It features a lot of irrational behaviour on the Brain’s part. I’m not particularly fond of this story but as usual, Asimov’s rationale is perfectly logical.

The book then moves on to 2032, a year that poses a completely different challenge to Susan. A Turing with a twist. In Evidence (1946), Stephen Byerley is a brilliant district attorney running for mayor, when one of his opponents accuses him of being a robot. How do you prove someone is a robot when the subject is not cooperating and very aware of his rights? Written during the aftermath of the second world war, it is easy to see what Asimov (of Russian Jewish descent himself) was aiming at. It is the most politically charged story in the book, with a lot of it focussing on the suspicion and outright hatred of robots despite the fact they are incapable of harming a human being. Where Asimov usually explains the entire plot to the reader in detail, this story is certainly food for thought.

Interestingly enough I, Robot then goes to show us some suspicion of robots might actually be warranted. In The Evitable Conflict (1950), set in 2052, Calvin has realized that robots rule the world. They are responsible for the allocation of goods and services and the division of labour of the entire planet, which by that time is divided into four super states. Calvin is called upon to explain apparent imperfections in the solution the robots provide. These turn out to have a perfectly reasonable explanation in line with the three laws of course. This story has aged very badly, Asimov’s future, at this point in time, seems positively silly, although from his perspective it might not have been entirely impossible. It was not my favourite part of the book though. Partly because of Asimov’s tendency to explain everything and partly because of the fact that the plot is mostly a guided tour though planetary government in 2052.

With I, Robot Asimov lays the foundation of what would become one of the three main series in his career as a science fiction writer. He is not technically a good writer (at this point in his career at least) but back in the days where science fiction was very much seen as the literature of ideas, you probably couldn’t do much better than Asimov. He had ideas and was not afraid to explain them at length. For the modern reader a lot of I, Robot is dated but with lasting contributions to the genre such as the three laws of robotics and the positronic brain, it is one of the novels that shaped the genre. One of the thoughts that kept returning while reading this novel is just how many things Asimov discussed that were in the experimental stage at the time, or didn’t exist at all. All things considered, I think it deserves at least some of the praise that is heaped on it.

The Horror! The Horror! – Poppy Z. Brite

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. This is the start of a new series where Dee explores the darker side of genre fiction and it’s practitioners. Be sure to visit his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com for more genre goodness.

This is not going to be a easy to write as I thought. I had my first line all planned out and can still use it:

This is not going to be a easy to write as I thought. I had my first line all planned out and can still use it:

"Of course her real name is not Poppy Z. Brite. It’s a pseudonym used by Melissa Ann Brite, born May 25, 1967 in New Orleans, Louisiana."

I got that much by glancing at Brite’s Wikipedia entry. But further down the page I picked up this bit of information: "Brite is a transgender man, born biologically female. He has written and talked much about his gender dysphoria/gender identity issues. He self-identifies with gay males, and as of August 2010, has begun the process of gender reassignment."

That I didn’t know, but it goes some ways towards explaining why almost all of Brite’s male characters, whether they are vampires, musicians, artists, drug dealers, or serial killers tend to be gay men.

When I decided to read some horror fiction, I thought I would start with Brite because I had heard the novels were good, moody, sexy, and very bloody. She, as I thought at the time, represented the new generation of horror writers, steeping the novels in a gothic punk atmosphere that no other writer at the time — the early 1990’s — had explored. Although she wrote stand alone novels, some characters and settings reappeared, creating a world of the supernatural and the grotesque that alternated between Missing Mile, North Carolina and New Orleans. (I love that name, Missing Mile.)

Brite’s horror publishing career lasted only half a decade and produced three novels and two volumes of short stories. His first novel, Lost Souls, he began while still a teenager. When his last horror novel, Exquisite Corpse came out in 1996, he was 29. Brite then turned to writing comic novels centered around the New Orleans restaurant scene. For the past several years, he as been on an official hiatus from writing at all. But I think with Lost Souls, Drawing Blood, and Exquisite Corpse Brite has left a significant legacy in the horror genre. (I have not read the short stories.)

Lost Souls is a lushly over-written, almost plotless tale of vampires traveling the country in what must be a very smelly van given their sloppy feeding habits. Their handsome leader, Zillah, keeps things somewhat under control with his more party-minded friends Molochai and Twig. They meet up with a confused, not yet out of the vampire closet fifteen-year old named Nothing. Nothing and Zillah almost instantly hit the sack. In a scene that involves killing his best friend, Nothing learns he is a vampire. Later he learns that Zillah, due to a one night stand in New Orleans many years ago, is his father, a fact that does not put a crimp in the sexual activity. They hang out in Missing Mile, NC, which is a much hipper place than it sounds. They seduce some people, they kill some people, they meet up with an old friend from New Orleans and relocate. There they get involved with some other kinky types — there’s no point in going any further with this. Brite’s enthusiastic prose keeps things happening if not exactly moving in any particular direction. It’s fun, although long.

Lost Souls is a lushly over-written, almost plotless tale of vampires traveling the country in what must be a very smelly van given their sloppy feeding habits. Their handsome leader, Zillah, keeps things somewhat under control with his more party-minded friends Molochai and Twig. They meet up with a confused, not yet out of the vampire closet fifteen-year old named Nothing. Nothing and Zillah almost instantly hit the sack. In a scene that involves killing his best friend, Nothing learns he is a vampire. Later he learns that Zillah, due to a one night stand in New Orleans many years ago, is his father, a fact that does not put a crimp in the sexual activity. They hang out in Missing Mile, NC, which is a much hipper place than it sounds. They seduce some people, they kill some people, they meet up with an old friend from New Orleans and relocate. There they get involved with some other kinky types — there’s no point in going any further with this. Brite’s enthusiastic prose keeps things happening if not exactly moving in any particular direction. It’s fun, although long.

Drawing Blood returns to Missing Mile where the sole survivor of a family massacre returns twenty years later to confront family ghosts. He meets up with a computer hacker on the run from the feds and guess what, they spend almost all their time in bed — or on the floor or in the shower. They are at the age when erections are so hard they ache. If the traditional horror audience of 16 to 25 year old males actually read this book, things have changed. Or maybe that demographic only applies to horror movies and not horror fiction. Drawing Blood is a haunted house story of sorts, with lots of rock and roll, gay sex, and mushroom ingestion. It is also a romance with a happy romance ending that I personally thought was out of place, but I suspect Brite, or at least his publishers, know their audience.

Drawing Blood returns to Missing Mile where the sole survivor of a family massacre returns twenty years later to confront family ghosts. He meets up with a computer hacker on the run from the feds and guess what, they spend almost all their time in bed — or on the floor or in the shower. They are at the age when erections are so hard they ache. If the traditional horror audience of 16 to 25 year old males actually read this book, things have changed. Or maybe that demographic only applies to horror movies and not horror fiction. Drawing Blood is a haunted house story of sorts, with lots of rock and roll, gay sex, and mushroom ingestion. It is also a romance with a happy romance ending that I personally thought was out of place, but I suspect Brite, or at least his publishers, know their audience.

And what to make of Exquisite Corpse? Brite says his original publishers turned it down because it was too extreme. They would have had a point. The descriptions of necrophilia, torture, and cannibalism are like nothing in the previous novels. The book has at least a couple of images that unfortunately will most likely always be with me. But her publishers might also rightly have considered this novel something of a mess. HIV and AIDS are prominent elements in the story, and perhaps the serial killers are meant to represent the death sentence the disease was considered at the time. This is Brite’s best writing. The grotesque sex is like the Marquis de Sade minus all the frou-frou. or Georges Baitaille without the pretension. What ever was intended, Exquisite Corpse might best be considered grand guignol fun. It is also a book I would never recommend to anybody I know, fearing recriminations.

And what to make of Exquisite Corpse? Brite says his original publishers turned it down because it was too extreme. They would have had a point. The descriptions of necrophilia, torture, and cannibalism are like nothing in the previous novels. The book has at least a couple of images that unfortunately will most likely always be with me. But her publishers might also rightly have considered this novel something of a mess. HIV and AIDS are prominent elements in the story, and perhaps the serial killers are meant to represent the death sentence the disease was considered at the time. This is Brite’s best writing. The grotesque sex is like the Marquis de Sade minus all the frou-frou. or Georges Baitaille without the pretension. What ever was intended, Exquisite Corpse might best be considered grand guignol fun. It is also a book I would never recommend to anybody I know, fearing recriminations.

Brite’s three novels are quickly becoming period pieces, and you have to find them squeezed onto the shelves surrounded by all the paranormal romance and zombie crap that dominates the field. I like to imagine some unsuspecting Laura K. Hamilton fan will pick up Exquisite Corpse and live to regret it.

GMRC Review: Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Childhood’s End never won an award, but the Hugo wasn’t awarded for 1954, and there were no other science fiction awards at the time. It does, however, show up on the biggest "best of" lists included on Worlds Without End for which it would be eligible (except the ISFDB 100, surprisingly). It continues to be considered a classic nearly six decades after its initial publication as a Ballantine paperback. I recall it from my teenage years as being considered, pretty much by acclimation of science fiction fans and professionals, one of the best and most important SF novels, and I agreed at the time. It was voted the eighth best SF novel of all time in the 1998 Locus Best SF Novels of All-Time poll. There’s always a danger revisiting SF this old—predictions have been proved wrong, writing styles tended to be less engaging, cultural influences from the writers’ own background lead to anachronistic attitudes among characters. So, how does Childhood’s End hold up? Will it continue to be pointed to as a classic of the field?

Childhood’s End never won an award, but the Hugo wasn’t awarded for 1954, and there were no other science fiction awards at the time. It does, however, show up on the biggest "best of" lists included on Worlds Without End for which it would be eligible (except the ISFDB 100, surprisingly). It continues to be considered a classic nearly six decades after its initial publication as a Ballantine paperback. I recall it from my teenage years as being considered, pretty much by acclimation of science fiction fans and professionals, one of the best and most important SF novels, and I agreed at the time. It was voted the eighth best SF novel of all time in the 1998 Locus Best SF Novels of All-Time poll. There’s always a danger revisiting SF this old—predictions have been proved wrong, writing styles tended to be less engaging, cultural influences from the writers’ own background lead to anachronistic attitudes among characters. So, how does Childhood’s End hold up? Will it continue to be pointed to as a classic of the field?

I suspect the answer to that last question will be "yes" for a long time to come. Sure, there are a few details that stick out as dating the novel. As in all ’50s (and quite a bit of later) science fiction, calculating and problem-solving computers are predicted, but not digital data storage and instant access to information. Despite extreme technological advances, people still use paper and photographic film. There is some reflexive sexism—sexual freedom and attitudes improve, but women still seem to be tied to their reproductive roles, while men are the "thinkers and doers." These details are noticeable, especially considering that Clarke is describing a future technological and social utopia, but they are very much in the background, and thus easy to ignore, since the novel’s themes and ideas are not much concerned with them.

Arthur C. Clarke‘s prose is little more than serviceable, but it does open up at times when describing the wondrousness of alien worlds, vistas of incomprehensible scale, or the sublimity of humanity’s evolution in the concluding section.

"Through the clash and tug of conflicting gravitational fields the planet travelled along the loops and curves of its inconceivably complex orbit, never retracing the same path. Every moment was unique; the configuration which the six suns now held in the heavens would not repeat itself this side of eternity. An even here there was life. Though the planet might be scorched by the central fires in one age, and frozen in the outer reaches in another, it was yet the home of intelligence. The great, many-faceted crystals stood grouped in intricate geometrical patterns, motionless in the eras of cold, growing slowly along the veins of mineral when the world was warm again. No matter if it took a thousand years for them to complete a thought. The universe was still young, and Time stretched endlessly before them…"

Such descriptions are especially attention-getting when contrasted with the straightforward prose more typical of the novel.

Characterization is minimal, as each major section of the novel introduces a few characters to play important roles or represent prevalent attitudes necessary to move the story forward. But these characters perform these roles well, and seem believable enough. In fact, given the nature of the story, I was expecting much less characterization in the usual sense, since no individual can have much "stage time" in a novel of around two-hundred fifty pages that covers a couple of centuries of human history. And the most important character in Childhood’s End is the human race itself, a point that becomes increasingly clear as the novel progress. It is humanity’s potential for "character development" that is at the heart of the book. Clarke is interested in the potential for human development. His ideas could have been presented in non-fiction form, but he chose to do so in the form of a novel. It could easily not have worked. The fact that it is able to present such big ideas, and still work well as a novel, is impressive.

Clarke seems to be commonly thought of as a writer more interested in technology than characters—the alien ship in Rendezvous with Rama; the space elevator in Fountains of Paradise—but the future depicted in Childhood’s End is not mainly technological. Rather, it is a step in human evolution, preceded by a social utopia (with a little help from some aliens).

The space race is proceeding, and humanity seems on the brink of war, when the Overlords arrive on Earth. Speaking through a single representative "supervisor"—Karellen, the only character to be involved in every stage of the story—the alien Overlords impose utopia on the human race. How would we respond to a truly benevolent occupation? Would we be angry that we could no longer fight wars, even if our conquerors also removed any possible reason for conflict? Technically, humanity was not entirely free, but individual freedom was not interfered with as long as no one harmed anyone else. And all material needs are met, so there is nothing to fight over. Empires often believe that they are improving the lives of those whom they conquer, and such attitudes are justifiably criticized. What if the conquerors are right?

Some object (especially on religious grounds) to the loss of freedom, but humanity soon settles gratefully into a "Golden Age."

"By the standards of all earlier ages, it was Utopia. Ignorance, disease, poverty and fear had virtually ceased to exist. The memory of war was fading into the past as a nightmare vanishes with the dawn; soon it would lie outside the experience of all living men. With the energies of mankind directed into constructive channels, the face of the world had been remade."

Production is largely automated, and resources previously used for war and defense are made available for construction and consumption. Crime is practically eliminated, since there is no poverty, and the Overlords can maintain complete surveillance over the planet. Leisure is greatly increased, psychological problems fall away, and rationality prevails. People can easily travel to wherever they want and live wherever they like (flying cars!). "It was a completely secular age… The creeds that had been based upon miracles and revelations had collapsed utterly." I find this sort of speculation fascinating, and I’m sure it’s a big part of the appeal of the novel, especially to younger readers. Would it really play out this way? It’s a hopeful thought, and does not seem impossible, given the circumstances. What if the world ran on truly rational principles? That is the question posed by the "tyranny" of the Overlords. But the sticky question of freedom remains. It is still not a perfect world, and nagging questions remain. What comes next for humanity, when there seems nothing to strive for? Why have the Overlords forbidden space exploration? What is their real motivation?

Production is largely automated, and resources previously used for war and defense are made available for construction and consumption. Crime is practically eliminated, since there is no poverty, and the Overlords can maintain complete surveillance over the planet. Leisure is greatly increased, psychological problems fall away, and rationality prevails. People can easily travel to wherever they want and live wherever they like (flying cars!). "It was a completely secular age… The creeds that had been based upon miracles and revelations had collapsed utterly." I find this sort of speculation fascinating, and I’m sure it’s a big part of the appeal of the novel, especially to younger readers. Would it really play out this way? It’s a hopeful thought, and does not seem impossible, given the circumstances. What if the world ran on truly rational principles? That is the question posed by the "tyranny" of the Overlords. But the sticky question of freedom remains. It is still not a perfect world, and nagging questions remain. What comes next for humanity, when there seems nothing to strive for? Why have the Overlords forbidden space exploration? What is their real motivation?

That last issue is addressed in the concluding part of the novel. The achievement of Utopia is not childhood’s end, but a final step in the fostering of the ultimate evolution to adulthood. It involves Clarke’s interpretation of the possible meaning of mysticism and psychic phenomena, the existence of a universal "Overmind," and the meaning of the Overlords’ task. Utopia will be left behind for a future humanity cannot yet comprehend. I’m tempted to quote some of the passages describing this, as they are among the best in the book, but suffice it to say that the final chapter of Childhood’s End remains one of the most gripping in all of science fiction.

Considering humanity itself as the main character of Childhood’s End, "characterization" is actually Clarke’s major strength in this novel. We follow the character from childhood to maturity—from an existence overly determined by emotion and impulse, to one governed by rationality, to "the end of Man… an end that repudiated both optimism and pessimism alike." I questioned the journey much of the way, as my cynical attitude wanted to intrude. I kept looking for the fatal flaw in Clarke’s arguments. It remains thought-provoking. About halfway through the novel, I gave up looking for narrative or philosophical flaws, and considered the possibilities…

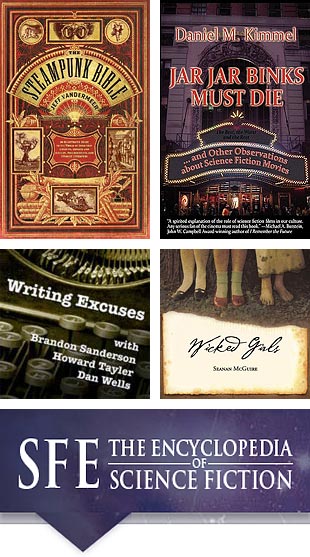

Related Works, Unchained!

Fourth in our series of posts helping you locate Hugo nominees (short story, novelette, and novella preceding) concerns Best Related Work, the Hugo committee’s catch-all category. Unlike the previous three categories, a Worldcon membership will not get you any Related Works. We still recommend that you get at least a $50 supporting membership, because that will nab you digital copies of all five novels, six novellas, five novelettes, and five short stories — a bargain.

Fourth in our series of posts helping you locate Hugo nominees (short story, novelette, and novella preceding) concerns Best Related Work, the Hugo committee’s catch-all category. Unlike the previous three categories, a Worldcon membership will not get you any Related Works. We still recommend that you get at least a $50 supporting membership, because that will nab you digital copies of all five novels, six novellas, five novelettes, and five short stories — a bargain.

The good news: Two of the related works are already free and online. The other three, however, will cost you something:

- The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Third Edition, though originally published in hardback (in its first two editions), is now available online for free. If you want a paper copy for coffee table, you’ll need to order from England.

- Writing Excuses, Season 6 is a podcast, and can be heard for free here. You’ll need to navigate to season six.

- Jar Jar Binks Must Die… and Other Observations about Science Fiction Movies by Daniel M. Kimmel is $14.99 in dead tree format at Amazon, or digitally in Kindle or Nook editions for only $9.99.

- Wicked Girls is an album by Seanan McGuire and can be ordered for $15 through CD Baby, which also allows you to sample portions of each song. Who knew Seanan could sing?

- The Steampunk Bible edited Jeff VanderMeer and S. J. Chambers has gotten a lot of press over the past year, so its inclusion is no surprise to WWEnders.

Links to all of the award winning novels are, as always, available through BookTrackr.

GMRC Review: Non-Stop by Brian Aldiss

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed.

Published in 1958, Non-Stop (a.k.a. Starship in the UK printing) was Brian Aldiss’ first novel, and it uses as its central conceit that well-trodden SF trope, the generation ship. These are enormous, self-sustaining star-ships that can house and support multiple generations of humans living within them as the ship makes its slow way from one star to another. Only the first generation will know Earth, and only the last ones will know their destination; the middle generations will know only the ship. Barring faster-than-light travel or some form of suspended animation, this is the only way for humans to effect interstellar travel. The idea was posited in the late 1920′s/early 1930′s, and has appeared often throughout SF, and 2009′s Pandorum and Mary Robinnette Kowal’s 2011 Hugo-Award-winning short story “For Want of a Nail” (a very good story, I might add), show that there is still traction and interest in this well-worn trope. Of course, the ubiquitous element of the generation star-ship sub-genre is that something goes terribly wrong during the voyage. In the early 1940′s, Heinlein published two stories (later collected into Orphans of the Sky) about a generation starship in which the middle generations of the generation ship have forgotten that they are on a starship, since it is the only world they know, causing shipboard society to erode into a more primitive, superstitious state. Aldiss, loved the concept, but disliked Heinlein’s execution, and Non-Stop is his response.

Published in 1958, Non-Stop (a.k.a. Starship in the UK printing) was Brian Aldiss’ first novel, and it uses as its central conceit that well-trodden SF trope, the generation ship. These are enormous, self-sustaining star-ships that can house and support multiple generations of humans living within them as the ship makes its slow way from one star to another. Only the first generation will know Earth, and only the last ones will know their destination; the middle generations will know only the ship. Barring faster-than-light travel or some form of suspended animation, this is the only way for humans to effect interstellar travel. The idea was posited in the late 1920′s/early 1930′s, and has appeared often throughout SF, and 2009′s Pandorum and Mary Robinnette Kowal’s 2011 Hugo-Award-winning short story “For Want of a Nail” (a very good story, I might add), show that there is still traction and interest in this well-worn trope. Of course, the ubiquitous element of the generation star-ship sub-genre is that something goes terribly wrong during the voyage. In the early 1940′s, Heinlein published two stories (later collected into Orphans of the Sky) about a generation starship in which the middle generations of the generation ship have forgotten that they are on a starship, since it is the only world they know, causing shipboard society to erode into a more primitive, superstitious state. Aldiss, loved the concept, but disliked Heinlein’s execution, and Non-Stop is his response.

The story follows Roy Complain, a hunter for the nomadic Greene Tribe that crawls its way through the vine-filled decks and hallways, slashing the ‘ponics, looting the rooms they come across, and leaving nothing useful in their wake to dissuade competitors. Roy has prospects, and life seems pretty decent: the tribe eats well, everyone adheres to the religion of Psychology, and he has hopes of being elevated from hunter to guard (giving him access the prime loot). But then his mate bugs him to come on a hunting trip with him, and she is captured by a neighboring tribe. Shamed and angry, Complain questions his place in the tribe and the tribe’s place in the grand scheme of things and so joins a renegade Priest named Marapper along with a handful of Greene tribesman on a wild adventure through unexplored corridors. Their goal is to find the fabled civilization of Forwards, and eventually the Captain of the ship. Of course, Roy doesn’t believe that his world is really a ship, but strange things happen along the way that shake his beliefs in who he is, why he is there, and who he can trust.

Non Stop Adventure: What Non-Stop Does Well

Non-Stop really doesn’t stop; it’s a brisk novel that rarely drags, which works both for and against the narrative. This pace benefits the narrative in that it keeps things interesting by keeping them moving: you can count on something new always lurking just around the bend. There is plenty of action, particularly towards the end, where the novel takes on a frenzied pace and bulls it’s way to the final conceptual breakthrough or revelation.

Actually, knowing that they are on a generation ship is a revelation Roy has later on and thus a kind of minor spoiler (sorry, dear readers), but A) that twist is general knowledge in regards to this novel and B) Aldiss includes plenty of other big surprises that make what happened to the ship just as interesting as what it is, if not more so. The characters know some things about the ship and the artifacts they find, but many truths about their environment have been lost to time and strife among the survivors. It’s interesting to note “the givens,” which are the things that the characters take for granted about their surroundings and how they interact with it. No one sees anything wrong in the hydroponically-grown plants that have burst their confines and overtaken most of the ship. The regularity of their environment (decks, doorways, overhead lighting) is seen as a part of nature. Indeed, when one character finally sees a real sun, he remarks that he expected it to be square just like a giant version of one of the lights within the ship. Aldiss paints a fairly restrictive, claustrophobic picture of life on the ship throughout the novel, which adds nicely to the sense of menace and paranoia built into the plot. I think I might wig out and run amok (which some characters do) due to the unceasing regularity of the environment only broken up by the thick, choking vines. The star-ship is a familiar, orderly setting that is defamiliarized and rendered strange in Aldiss’ work.

The early part of the novel has the strongest sociological speculation in it which, sadly, the story moved away from it fairly quickly to keep things moving. The way the Greene tribe is organized, the rituals and social structures they have developed, were very interesting to me as it illustrated how the people of the ship have adapted to their environment and to the needs of survival while maintaining a semblance of sanity and happiness. For example, children are weaned away from parents and siblings very early, partly, I expect, due to the ersatz religion of psychology (which enshrines consciousness as defined by Freud and Jung) but also to dissuade large families and keep the population manageable. Men don’t meet each other’s eyes, and the common greeting is “Expansion to your Ego,” with the response being “at your expense,” as an explicit albeit civil representation of the psychological power games of respect and abasement we all play. It was interesting and I had hoped for more, but for what it was I enjoyed it.

The characters held a lot of promise in the beginning for me. Roy Complain ultimately reads like a a violent, fairly unremarkable, knuckle-dragging hunter/warrior, but early on he piqued my interest with his encroaching existential crisis: why am I here, why are we here, who are we, what is this place, really? His band of adventurers seemed like a nice mix as well: the uptight Valuer (merchant/trader), the twitchy warrior, the secretive storyteller, and, most intriguing of all, the power-hungry and opportunistic priest Marapper. Marapper is a great character to love and hate: he is devious, backstabbing, dishonest, and alternately self-aggrandizing and self-abasing (whichever benefits him most at the moment).

Overall, what I enjoyed most from this novel was the growing sense of claustrophobia and menace that underlies the exploration of this familiar setting (the starship) rendered strange through the characters’ limited understanding of their environment. This ominous atmosphere was at its prime when the non-human creatures start to appear, some of which really creeped me out (I have a problem with moths, so moths with psychic powers in a confined, claustrophobic space makes me feel uncomfortable to say the least). The action and revelations kept a brisk pace and didn’t let things drag much, and early on in particular the ways in which Complain wrestles with the outward pressures of the tribe and the inward pressures compelling him to leave and discover what is really going on were palpable and helped me sympathize with him a great deal.

Complaints for Complain: Where Non-Stop Could Have Been Better

I found myself frequently frustrated at the inconsistencies in the book’s sociological/phenomenological perspective. To provide an example, early on in the book, Marapper reads aloud from a technical manual he found and Roy doesn’t understand much of what he is hearing (he only knows the syllables), but later Roy and his love interest read through the Captain’s diary without linguistic difficulty even though they are separated from the author by many, many societal decay generations. Which is it, can they read or not? Also, Aldiss frequently uses contemporary cliches or turns of phrase that are way too out of place for the third-person limited perspective of Roy Complain. The best articulation I found of this was from a review on the website Geek Chocolate:

While not unintelligent, the tribes are most certainly uneducated, and told from Complain’s point of view, the novel should reflect this, yet the reader’s vicarious rendering is described using vocabulary that would be beyond his comprehension. “The tight spiralling traced by the rifling in the barrel” would be meaningless to him, as the only projectile weapon the tribes have is bow and arrow, and he is likely similarly ignorant of ancient Greek musical notation, yet apparently the atmospheric systems sound “like a proslambanomenos implementing a sustained chord.”

Aldiss’ writing is good and heart-wrenching in places, but in a novel of this type–where one culture is encountering another that is significantly different and more advanced–the writing should reflect the phenomenological experience of the characters. For example, we know its just a swimming pool, but to Roy–who hasn’t seen so much water before–it’s an awe-inspiring ocean, and the narrative should help us experience that with Roy. It does in places, but inconsistencies in the tribes’ level of education and technological understanding, and Aldiss’ use of contemporary cliches and turns-of-phrase, pulled me out of the experience of encountering the mystery of the ship as the characters perceive it. This made me feel like the worldbuilding–the construction of the world as the characters understood it–was only half done, or that Aldiss was defeating himself in trying to evoke the strange with familiar, contemporary narrative devices.

While I had great enthusiasm for the characters in the beginning, by the end I felt that characterization in this book was fairly flat, which may be the effect of the non-stop, briskly-paced narrative. Roy seems primed to under go some kind of change as his worldviews (literally) are challenged, but he basically remains a predictable, short-tempered hunter-warrior throughout. Aldiss tries to signal a change in Roy that I either didn’t get or that didn’t feel warranted by the narrative. There is one moment when the whole ship is going ape that his love interest, Vyann, reflects that at least he is keeping his humanity and is changing into some kind of better person… at the same moment that Roy, elsewhere, is beating and threatening someone to compel his cooperation. He didn’t change all that much, and thus the character arc was pretty flat and forced if anything. Perhaps this is because the narrative can’t stop to contemplate these changes in more depth and detail, so characters kind of remain in given archetypes. Roy’s love interest, Vyann, begins as a cold, calculating woman who represents the more civilized, advanced people of the Forwards section of the ship, but she melts like butter for Roy. Once again, to quote the review on Geek Chocoloate (because I can’t say it any better): “Laur Vyann, representing the more advanced Forwards section, [is] cold and efficient, yet apparently waiting for the right inbred knuckle-dragger from the rear section of the ship to shamble along and unleash the woman within.” This is a very typical example of the “male gaze,” but one that renders a strong, seemingly complex female character into a simple damsel. By the end, only Marrapper with his barely-contained egoism and opportunism remained interesting to me.

While I had great enthusiasm for the characters in the beginning, by the end I felt that characterization in this book was fairly flat, which may be the effect of the non-stop, briskly-paced narrative. Roy seems primed to under go some kind of change as his worldviews (literally) are challenged, but he basically remains a predictable, short-tempered hunter-warrior throughout. Aldiss tries to signal a change in Roy that I either didn’t get or that didn’t feel warranted by the narrative. There is one moment when the whole ship is going ape that his love interest, Vyann, reflects that at least he is keeping his humanity and is changing into some kind of better person… at the same moment that Roy, elsewhere, is beating and threatening someone to compel his cooperation. He didn’t change all that much, and thus the character arc was pretty flat and forced if anything. Perhaps this is because the narrative can’t stop to contemplate these changes in more depth and detail, so characters kind of remain in given archetypes. Roy’s love interest, Vyann, begins as a cold, calculating woman who represents the more civilized, advanced people of the Forwards section of the ship, but she melts like butter for Roy. Once again, to quote the review on Geek Chocoloate (because I can’t say it any better): “Laur Vyann, representing the more advanced Forwards section, [is] cold and efficient, yet apparently waiting for the right inbred knuckle-dragger from the rear section of the ship to shamble along and unleash the woman within.” This is a very typical example of the “male gaze,” but one that renders a strong, seemingly complex female character into a simple damsel. By the end, only Marrapper with his barely-contained egoism and opportunism remained interesting to me.

The brisk pace of the plot doesn’t only harm characterization, however, as overall plot structure suffers as well. The plot is facilitated by a series of lucky breaks or coincidental revelations that help drive the action and, after a while, felt fairly contrived. The novel moves quickly enough though that it didn’t bother me much as long as I didn’t think about it much, but there were several plot elements that didn’t feel resolved. The big find of the Captain’s diary is just a big data dump that isn’t adequately explored, the threat of the belligerent non-humans doesn’t go beyond being a nuisance, and the conclusion itself feels rather abrupt.

Concluding Thoughts

Despite it’s flaws, I can see why Non-Stop was re-printed in the SF Masterworks series. While the world-building felt inconsistent and the characters half done, Non-Stop is still enjoyable since it maintains a brisk pace, has plenty of action, keeps the discoveries rolling, and houses it all in a menacing but intriguing environment of the starship-turned-wilderness. It’s an interesting exemplar of how sociological concerns play into the generation ship narrative and indeed into all space exploration stories.

Philip K. Dickathon: Now Wait for Last Year

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll keep posting them until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

I hate it when this happens. I try out a brand new hallucinogenic drug only to find out that it is addictive after a single use. Then, while suffering withdrawals, I’m offered help only if I agree to spy on my estranged husband who is now special physician to the ailing Sec. Gen of the United Nations Gino Molinari. I take more of the drug to get me through the trip to the White House in Cheyenne, Wyoming, only to find that the drug messes not only with my sense of time but with time itself. I find myself stuck in a cow pasture in an auto-cab in the year 1935. The cab cannot make it to Cheyenne without refueling, and so we have to wait for the effects of the drug to wear off so we will be returned to the mid 21st century where the super-refined protonex that fuels the cab will once again be available.

I hate it when this happens. I try out a brand new hallucinogenic drug only to find out that it is addictive after a single use. Then, while suffering withdrawals, I’m offered help only if I agree to spy on my estranged husband who is now special physician to the ailing Sec. Gen of the United Nations Gino Molinari. I take more of the drug to get me through the trip to the White House in Cheyenne, Wyoming, only to find that the drug messes not only with my sense of time but with time itself. I find myself stuck in a cow pasture in an auto-cab in the year 1935. The cab cannot make it to Cheyenne without refueling, and so we have to wait for the effects of the drug to wear off so we will be returned to the mid 21st century where the super-refined protonex that fuels the cab will once again be available.

Actually that has never happened to me. But it happens to Kathy Sweetscent in Now Wait for Last Year, and true to the spirit of PKD‘s novels this wild scene is barely a sidebar to what — or whatever — the book is about. Kathy will make it to Cheyenne, where the time-traveling aspects of the drug JJ-180 will mess with her life and that of her long-suffering, at least in his own mind, husband, Dr. Eric Sweetscent. He has an obese, hypochondriac despot to keep alive while earth is embroiled in a losing war between ‘Starmen and reegs. Earth has teamed with the ‘Starmen because they are humanoid. The reegs are six-foot tall bugs who must communicate through boxes that resemble training potties. But they are also winning the war. And ‘Starmen are infiltrating earth, and Molinari, known affectionately as The Mole, may actually be at death’s doorstep, or he might be yet another of the simulacra he has had made of himself, one of which is his young, vibrant leader self while another is a bullet-riddled corpse lying in a glass coffin.

Molinari is both a buffoon and shrewd politico. His constantly failing body may only be a ruse to get out of awkward meetings with the overbearing Frenesky, leader of the ‘Starmen. I pictured him as a character actor whose name I cannot remember, but PKD himself thought of him as a combination of Christ, Abraham Lincoln, and Mussolini. (That was a personality triad PKD attributed to several of his favorite characters.)

The plot starts running out of steam towards the end, but there are classic PKD moments of paranoia, intrigue, and absurdity. Now Wait for Last Year has made it into the three volume set of PKD novels distributed by the Library of America, so its reputation must be pretty good.

GMRC Review: The Brothel in Rosenstrasse by Michael Moorcock

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fifth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fifth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

In my attempt to combine some of my reading challenges, I decided to read Michael Moorcock‘s The Brothel in Rosenstrasse for the GMRC. The "brothel" in the title fulfills the "house" requirement in Beth Fish’s Readers Challenge. Before I chose this book, I did a little research and learned that the book was the second in Moorcock’s Rickhardt von Bek trilogy but that I need not read the first book before reading the second.

In my attempt to combine some of my reading challenges, I decided to read Michael Moorcock‘s The Brothel in Rosenstrasse for the GMRC. The "brothel" in the title fulfills the "house" requirement in Beth Fish’s Readers Challenge. Before I chose this book, I did a little research and learned that the book was the second in Moorcock’s Rickhardt von Bek trilogy but that I need not read the first book before reading the second.

Von Bek is the first person narrator of the novel. As a sick, bedridden old man, von Bek writes a memoir about his secret affair with the sixteen-year-old, Alexandra, a daughter of a noble family. This affair took place in fin de siècle Mirenburg, a city located in the fictional central European nation of Waldenstein. Moorcock creates a lush, cosmopolitan, multicultural city, where Europeans come to enjoy the cafés, cabarets, opium dens, and, of course, the brothel, "Mirenburg’s greatest treasure," "protected by every authority and tolerated by the Church" (45). Unfortunately, the architectural beauty and joie de vivre of Mirenburg is destroyed by a civil war during the course of the book.

Before the war comes, Alexandra and von Bek live together in the Liverpool Hotel and take advantage of the lax stewardship of Alexandra’s parents (who are out of the country), her aunt (who is supposed to be responsible for Alexandra in their absence but farms her off to the housekeeper, who is tricked by her charge). Von Beck is infatuated by Alexandra but is also repulsed by her extreme willingness to play the role of his sex toy. He justifies his lifestyle as a debaucher and rake by writing "I live as I do because I have no need to work and no great talent for art; therefore my explorations are usually in the realm of human experience, specifically sexual experience, though I understand the dangers of self-involvement in this as in any other activity" (94). In order to keep his pupil Alexandra interested, von Beck begins taking Alexandra to the brothel, where they engage in threesomes, foursomes, sadomasochism and cocaine use.

When the war comes, Alexandra tells her family that she and her friends are joining refugees outside the city but instead she and von Bek are forced to seek refuge in the brothel once their hotel is bombed. Von Bek describes the brothel as "an integrated nation, hermetic, microcosmic" (49). However, while von Bek enjoys the clubby atmosphere of the salon and the dining table, Alexandra must hide in their room because they cannot risk her being recognized by another member of the nobility. Once von Beck relents and lets Alexandra appear, she begins to manipulate the citizens of the microcosm as the long siege of Mirenburg begins.

Von Bek’s memoir slips between his past in Mirenburg and his present as an invalid whose only human contact is with his manservant. Moorcock handles this in an interesting way as von Bek’s arguments (both vocal and silent) with the manservant Papadakis weave in and out of the memoir:

I can only admit now that I gave myself up to Eros deliberately, in the belief it does a man or woman good to make such fools of themselves occasionally, there are few risks much wilder and few which make us so much wiser, should we survive them. Papadakis stretches out his emaciated arms. I smell boiled fish. "It will do you good," he says in his half-humorous, half-insinuating voice; a voice once calculated during his own, brief Golden Age to rob the weak of any volition they might possess; but it had been the single weapon in his arsenal; he had used up all of his emotional capital by the time he was forty. (38)

Von Bek’s writing demonstrates his insecurity concerning Alexandra in the past and his fear of death in the present. The narrative has the fury of a man writing against time and to regain his past. He alternates between scenes of sexual excess and lush description that shows his love of Mirenburg, which he loves as much as Alexandra.

Von Bek’s writing demonstrates his insecurity concerning Alexandra in the past and his fear of death in the present. The narrative has the fury of a man writing against time and to regain his past. He alternates between scenes of sexual excess and lush description that shows his love of Mirenburg, which he loves as much as Alexandra.

There are no fantasy or supernatural elements in this book. Only Moorcock’s name and the fact that Rickhardt von Bek’s ancestor Ulrich is the protagonist of The War Hound and the World’s Pain connect The Brothel in Rosenstrasse to the fantasy genre; this book is a historical romance focusing on decadence and obsession. Unless WWE readers are also interested in historical fiction, I’d recommend this one for Moorcock completists only. The plot is thin, and the characters are weak and not really likeable. The city of Mirenburg is the star: the descriptions of the city are beautiful and his ability to situate the reader in a location is dazzling. I am looking forward to reading the other two books in the series but hope they are more driven by character and plot.

Moorcock has made his fictional brothel famous not only through the book but through song. The song was recorded by Michael Moorcock and Deep Fix in 1982. You can hear it on YouTube.

The lyrics are as follows:

Schmetterling says that all her girls are ladies

She won’t hand out keys to anyone who’s shady

It’s all done with taste, you must not seem a waster or a scoundrel

She’s kind and she’s warm, believes in good form

So don’t be hasty!The Brothel in Rosenstrasse all our girls are clean and game

The Brothel in Rosenstrasse, you don’t have to give your right namePlease don’t speak of despair, or anything that’s seedy

Please don’t admit you’re cynical and greedy

Your manner’s refined, your role is clearly defined, and so is the lady’s

The things that you do aren’t wicked or rude, because you need themThe Brothel in Rosenstrasse, all our girls are keen to please

The Brothel in Rosenstrasse, at reasonable fees

GMRC Review: To Your Scattered Bodies Go by Philip José Farmer

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog.

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog.

To Your Scattered Bodies Go

To Your Scattered Bodies Go

by Philip José Farmer

Published: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1971

Series: Riverworld Saga Book 1

Awards: 1972 Hugo Winner,

1972 Locus SF Nominated

The Book:

”Imagine that every human who ever lived, from the earliest Neanderthals to the present, is resurrected after death on the banks of an astonishing and seemingly endless river on an unknown world. They are miraculously provided with food, but with not a clue to the possible meaning of this strange afterlife. And so billions of people from history, and before, must start living again.

Some set sail on the great river questing for the meaning of their resurrection, and to find and confront their mysterious benefactors. On this long journey, we meet Sir Richard Francis Burton… and many other [people from history], most of whom embark upon searches of their own in this huge afterlife.” ~barnesandnoble.com

This is my fourth review for WWend’s Grand Master Reading Challenge. I’d never read any of Philip José Farmer’s work before, but I’d heard of the Riverworld series. I vaguely remember watching the Sci-Fi Channel adaptation in the early 2000s, but I’m pretty sure it strayed rather far from the story of the novel.

My Thoughts:

My favorite part of To Your Scattered Bodies Go was the setting and mystery of the Riverworld. It’s admittedly a very contrived environment, but that’s acknowledged in the story. Whether it is an afterlife arranged by some deity or a grand experiment arranged by some alien race, it is clear that the Riverworld was constructed with thought towards keeping the whole of humanity in comfort. The Riverworld was also presumably constructed to serve some unknown purpose for its mysterious creator(s). I enjoyed seeing the many characters’ ideas on this central mystery, and I also had fun imagining what the purpose could possibly be. In this case, I think the mystery might be much more fascinating than any actual answer that may be eventually given.

In the Riverworld, all of humanity, from all different cultures and historical periods, live together. With so many different perspectives and life philosophies, and so many real historical figures to draw on, I think this premise has a lot of potential. Unfortunately, I don’t really feel as though the novel capitalized on this potential. For one thing, the different cultures did not seem particularly distinct. For instance, a Neanderthal man seemed surprisingly similar in views and temperament to a Victorian gentleman. I feel like it could have been a much more interesting story if it had engaged with the dramatic differences in worldview between cultures that span the whole of human history.

While the story didn’t significantly feature cultural differences, it did cast a very cynical eye toward the tendency of human beings to create conflict. In a world where everyone was set on equal ground, with no pain, illness, or shortage of resources, people began almost immediately to establish hierarchies. Despite the fact that there was plenty of food, drink, and luxuries (drugs, etc.) for all, many were quick to use force to establish inequalities in wealth and power. This seemed very realistic to me. While I don’t think hierarchical thinking is THE tragic flaw in humanity, I do think that many people pursue power for power’s sake – not just to gain control of limited resources.

Despite its fascinating central mystery, and the opportunity to use the world to explore cultural differences and human nature, To Your Scattered Bodies Go seems to be mostly a boy’s adventure story. The characters were fairly flat and not very memorable beyond the brief recognition of their historical period or real-life counterpart. Each character tended to be introduced with an awkward little infodump about their previous life. There’s also a character who seems very much like an author insertion, and who constantly spouts off facts about the hero Sir Richard Francis Burton. I felt like, with so many people to choose from, a more compelling cast could have been constructed.

On that note, I was a little frustrated that, chosen out of all of human history, the hero and narrator was a Victorian gentleman explorer and the first villain was a Nazi, Hermann Göring. I think that, even in 1971, it must have already been a little hackneyed to use Nazis as an example of human evil and guilt. However, the situation was not quite as simple as that may make it sound, and Göring did prompt some interesting discussion of post-resurrection identity and culpability. The hero and narrator, Richard Burton, is essentially a real-life adventure hero, so I can see why he was an obvious choice for the protagonist. However, he manifested enough of the attitudes and views of the typical fictional Victorian gentleman explorer that I found him very irritating as a narrator. One of these typical attitudes is the remarkably blatant sexism that permeates the story. For a few quick examples:

On that note, I was a little frustrated that, chosen out of all of human history, the hero and narrator was a Victorian gentleman explorer and the first villain was a Nazi, Hermann Göring. I think that, even in 1971, it must have already been a little hackneyed to use Nazis as an example of human evil and guilt. However, the situation was not quite as simple as that may make it sound, and Göring did prompt some interesting discussion of post-resurrection identity and culpability. The hero and narrator, Richard Burton, is essentially a real-life adventure hero, so I can see why he was an obvious choice for the protagonist. However, he manifested enough of the attitudes and views of the typical fictional Victorian gentleman explorer that I found him very irritating as a narrator. One of these typical attitudes is the remarkably blatant sexism that permeates the story. For a few quick examples:

"She was a product of her society – like all women, she was what men had made her…”

"Even if she had been a whore, she had a right to be treated as a human being. Especially since she maintained that it was hunger that had driven her to prostitution, though he had been skeptical about that."

It seemed like Burton classified every woman he met as either a prude, a whore, or a nag, and he made it quite clear he had little interest in the women of the story outside of sex. It seemed that most of the female characters had little relevance to the story besides being sex resources for the male explorers. I know this may be a realistic representation of the attitude towards women in the 1800s, but that didn’t make it any less annoying. The narrator, the occasionally clunky writing, and the relatively flat characters dimmed my enthusiasm for the story, but I still think the novel has a really fun premise with lots of possibility for interesting stories to be told.

My Rating: 3/5

To Your Scattered Bodies Go is an adventure story set in a world that stretches along a massive river, where all of humanity is mysteriously resurrected. The novel’s strong points were the world itself and the characters’ attempts to determine its nature and purpose. The weaker points were poor characterization, lack of a strong sense of the multicultural tangle of the Riverworld, awkward writing, and the heavy dose of overt sexism brought in by the viewpoint character, a fictional version of the historical explorer Richard Burton. There were plenty of ideas to like in Farmer’s Riverworld, but, for me, they were not altogether enough to overcome the novel’s weaknesses. I am glad to have read To Your Scattered Bodies Go, but I doubt I will continue on with the rest of the series.

Grand Master Reading Challenge March Review Winner: RhondaK101

![]() The GMRC March Review Poll is now closed. The winner is RhondaK101 for her excellent review of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest. This win will come as no surprise to anyone who’s read Rhonda’s reviews and blog articles here on WWEnd. Congrats, Rhonda!

The GMRC March Review Poll is now closed. The winner is RhondaK101 for her excellent review of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest. This win will come as no surprise to anyone who’s read Rhonda’s reviews and blog articles here on WWEnd. Congrats, Rhonda!

As the winner, Rhonda will receive a GMRC T-shirt, a GMRC button and a set of commemorative WWEnd Hugo Award bookmarks as well as her choice of books from the WWEnd bookshelf. Runners up will be getting a GMRC button and a set of bookmarks in the mail. Great job to all who participated.

If you have any friends who are up for a reading challenge the GMRC is one that you can easily catch up on if you miss the start. Let ’em know it’s not too late to sign up and there is plenty of time to get in your reviews for April. There are more prizes to be won too so good luck!

Novellas, Unbound!

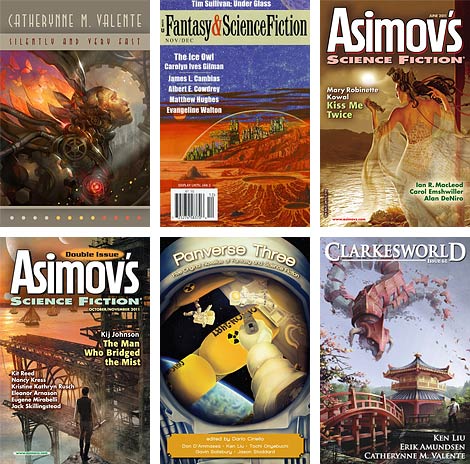

First, we posted links to all of the Hugo nominated short stories (all free and digital), then we followed up with the novelettes (mostly free and all digital), and now we have… novellas! Of the six nominated novellas, five are available digitally, and four are free. Considering Hugo defines a novella as being up to 40,000 words, that’s a lot of reading for not much.

Do remember that Chicon 7 (Worldcon 70) members get digital copies of all five novels, six novellas, five novelettes, and five short stories for FREE. Even if you don’t plan on attending Worldcon this year, you can get a supporting membership for only $50, and you’ll be able to vote.

If membership isn’t in the cards this year, you can still get the novellas (most of them for free):

- “Countdown” by Mira Grant (aka Seanan McGuire) (Orbit) is just $2.99 on Kindle, as well as Nook and Google Books.

- “The Ice Owl” by Carolyn Ives Gilman (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, November/December 2011) is the only nominated story that doesn’t seem to be available online in any format. I’ll keep looking, but, for now, the only way to get this story is by ordering the Nov/Dec issue in dead tree format.

- “Kiss Me Twice” by Mary Robinette Kowal (Asimov’s, June 2011) is free!

- “The Man Who Bridged the Mist” by Kij Johnson (Asimov’s, September/October 2011) is free!

- “The Man Who Ended History: A Documentary” by Ken Liu (Panverse 3) is in PDF format (so is ebookable) and is free!

- “Silently and Very Fast” by Catherynne M. Valente (Clarkesworld / WSFA) is free!

A note on the two stories that are not free: Countdown is a real book, published by Orbit, which sells digitally for $2.99. This, I think, is the beginning of a trend. Shorter stories are starting to sell on Kindle at less-than-novel prices. Even though the other books on this list are free, I think the trend to charge small amounts for novellas, novelettes, and even short stories means that otherwise unaccessable stories will have a longer shelf life, giving us more to read. While Seanan McGuire is being all cutting edge, “The Ice Owl”, by Carolyn Ives Gilman, does not seem to be available anywhere online. If that changes, we will update this article and let you know by tweet (@WWEnd).

Links to all of the award winning books are, as always, available through BookTrackr. So, now you have no excuse when someone asks you who you think should win. Get to reading!

Full Details

Full Details