The Old Weird: Series Introduction

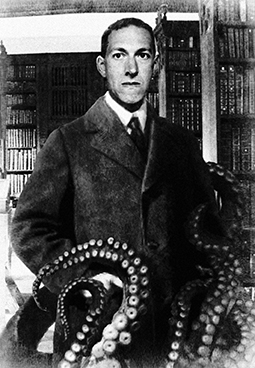

Over my long Christmas break, I decided to read some H. P. Lovecraft. Of course, I’d read a few Lovecraft stories here and there in anthologies, but I’d never read his work in any systematic way. I found a great complete (?) works e-text at Cthulhu Chick and started reading. It contains 63 short stories, novelettes, and novellas. As you can imagine, one can only read so many Lovecraft stories in a row before (1) the plots all start to run together or (2) one begins to question his or her own sanity. Between reading Lovecraft stories, I did what any good English professor does: Research! This led me to a host of Lovecraft precursors and contemporaries who wrote ghost, occult and supernatural stories—the writers of Victorian Gothic, horror and weird. I’m calling this series The Old Weird in order to show the readers that this will not be a blog dedicated to China Miéville and contemporary writers. In my exploration of the Old Weird, I discovered texts by William Hope Hodgson, Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen, Lord Dunsany, Robert W. Chambers, Seabury Quinn, M. R. James, and many others which I will explore as they set forth the parameters for the occult and horror stories that thrill us today.

Over my long Christmas break, I decided to read some H. P. Lovecraft. Of course, I’d read a few Lovecraft stories here and there in anthologies, but I’d never read his work in any systematic way. I found a great complete (?) works e-text at Cthulhu Chick and started reading. It contains 63 short stories, novelettes, and novellas. As you can imagine, one can only read so many Lovecraft stories in a row before (1) the plots all start to run together or (2) one begins to question his or her own sanity. Between reading Lovecraft stories, I did what any good English professor does: Research! This led me to a host of Lovecraft precursors and contemporaries who wrote ghost, occult and supernatural stories—the writers of Victorian Gothic, horror and weird. I’m calling this series The Old Weird in order to show the readers that this will not be a blog dedicated to China Miéville and contemporary writers. In my exploration of the Old Weird, I discovered texts by William Hope Hodgson, Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen, Lord Dunsany, Robert W. Chambers, Seabury Quinn, M. R. James, and many others which I will explore as they set forth the parameters for the occult and horror stories that thrill us today.

WoGF Review: A Discovery of Witches by Deborah Harkness

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. Ronda is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses.

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. Ronda is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses.

Somewhere online I read that A Discovery of Witches is “Harry Potter for adults.” Similarly, I described the book to a relative as “Twilight for smart people.” (Since I’ve never read any of the Twilight series, I’ll accept any of the invective that you want to pile on for my snobbery). However, a book like this will inevitably be compared to these two behemoths of popular culture. Magic? Check. A brooding vampire? Check. A forbidden romance? Check. A movie deal in the works? Check.

Somewhere online I read that A Discovery of Witches is “Harry Potter for adults.” Similarly, I described the book to a relative as “Twilight for smart people.” (Since I’ve never read any of the Twilight series, I’ll accept any of the invective that you want to pile on for my snobbery). However, a book like this will inevitably be compared to these two behemoths of popular culture. Magic? Check. A brooding vampire? Check. A forbidden romance? Check. A movie deal in the works? Check.

Deborah Harkness freely admits that the current magic-and-vampire craze inspired her to write A Discovery of Witches. She remembers walking through an airport bookstore and wondering if there are witches and vampires, what do they all do for a living? In response to that question, she gives us Diana Bishop, a Yale history professor and the last of a long line of American witches, and Matthew Clairmont, a neuroscientist, a fellow of All Souls, Oxford, and a vampire. Diana Bishop, in response to a childhood trauma, vows to give up all magic and buries herself in her research. Significantly, she researches early alchemical manuscripts, trying to show “how scientific this pursuit really was” (10). Her belief is that “[a]lchemy tells us about the growth of experimentation, not the search for a magical elixir that turns lead into gold and makes people immortal” (10).

GMRC Review: Hrolf Kraki’s Saga by Poul Anderson

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s seventh featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s seventh featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

Poul Anderson‘s Hrolf Kraki’s Saga is a retelling of the Icelandic saga by the same name. Scholars believe the Icelandic saga was composed between the mid-eleventh and the mid-thirteenth centuries. Most of the Icelandic sagas written during this time record the history of the settlement of Iceland (beginning in the late 800s) or the rise of the first families of Iceland. Famous examples of such are Erik the Red’s Saga and Njal’s Saga. Hrolf’s is different from these family sagas, as they are usually called. It is a legendary saga, set in a long ago and far away Denmark. Scholars date the events occurring in Hrolf’s Saga to the late fifth and early sixth centuries. Interestingly, Hrolf’s ancestors, who figure prominently in the saga, are probably the same historical figures who appear in the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf. The Scylding clan found in Beowulf is called the Sköldings in Hrolf’s: the Hrolf figure is Hrothulf in Beowulf; his grandfather is Halfdan/Healfdane; his father is Helgi/Halga; and his uncle is Hroar/Hrothgar.

Poul Anderson‘s Hrolf Kraki’s Saga is a retelling of the Icelandic saga by the same name. Scholars believe the Icelandic saga was composed between the mid-eleventh and the mid-thirteenth centuries. Most of the Icelandic sagas written during this time record the history of the settlement of Iceland (beginning in the late 800s) or the rise of the first families of Iceland. Famous examples of such are Erik the Red’s Saga and Njal’s Saga. Hrolf’s is different from these family sagas, as they are usually called. It is a legendary saga, set in a long ago and far away Denmark. Scholars date the events occurring in Hrolf’s Saga to the late fifth and early sixth centuries. Interestingly, Hrolf’s ancestors, who figure prominently in the saga, are probably the same historical figures who appear in the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf. The Scylding clan found in Beowulf is called the Sköldings in Hrolf’s: the Hrolf figure is Hrothulf in Beowulf; his grandfather is Halfdan/Healfdane; his father is Helgi/Halga; and his uncle is Hroar/Hrothgar.

Anderson was, of course, aware of Hrolf’s origins and connections. With these in mind, he created a tale that stays very close to its origins, yet expands to encompass the saga’s connections to other legends and stories. Anderson incorporates bits from other sources, such as Saxo Grammaticus’s Gesta Danorum and Snorri Sturlusson’s Poetic Edda to fill in the saga’s gaps In constructing his tale, Anderson thinks about the multiple paths that this legend might have taken as an oral tale. Clearly, one of those paths led from Denmark through many countries and centuries until it reached medieval Iceland where it was written down, but there are multiple paths of transmission for any oral tale. In his intro, he writes:

Outside the Norm: Announcing the Outside the Norm Reading Group

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

Over in the forum, several of us have been putting together an Outside the Norm Reading Group for the remainder of the year and continuing into the next. It will function much like a book club. We will read one book a month and will spend at least the first week of the following month discussing the book in the group. Emil has offered this format for discussion:

Over in the forum, several of us have been putting together an Outside the Norm Reading Group for the remainder of the year and continuing into the next. It will function much like a book club. We will read one book a month and will spend at least the first week of the following month discussing the book in the group. Emil has offered this format for discussion:

- Initial impression of the book

- Themes

- Particular theme that impressed

- Favorite scene/moment, etc.

We have planned books through next January, but we would love for this to continue longer and get your input for future books. We envision this as a fluid "book club" and hope that people will be able to join (and leave) according to their interest in the books we will discuss each month.

The July book is Victor Pelevin’s Omon Ra. We will discuss it during the first week of August. It is only 153 pages, so it will be easy to catch up this month.

The remaining schedule is:

- August: Ben Okri, The Famished Road

- September: José Saramago, Blindness

- October: Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita

- November: Angela Carter, Nights at the Circus

- December: Yevgeny Zamyatin, We

- January: Doris Lessing, Memoirs of a Survivor

Remember: We will discuss each book during the first week of the following month.

Feel free to offer up suggestions of science fiction, fantasy and horror books that you feel are "outside the norm," which we have been defining as books by women, persons of color, or non-US/UK authors. We have been using the Guardian list as a guide, but we certainly not limited to those books.

Please join us in the forum!

GMRC Review: The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s sixth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s sixth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

This will be the seventh Worlds Without End review of Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man. I wonder what new I might contribute; however, since I need to write a review of this Hugo winner to fulfill one of my other reading challenges, I’ll give this a shot as a pro and con list. This means that there will be spoilers. Be warned, if you have not read the book or want a more conventional review, choose one of the other reviews; they are good.

What I enjoyed:

1. The police procedural aspect.

I always thought that Asimov’s The Caves of Steel was the first detective science fiction novel. However, my research shows that Bester published a serial version of The Demolished Man beginning in January 1952 in Galaxy Science Fiction. Asimov’s serial of The Caves of Steel appeared in the same magazine in October to December 1953. These dates—in one sense—call into question the famous Asimov anecdote that he wrote The Caves of Steel to prove wrong John W. Campbell’s claim that mystery and science fiction were incompatible. If Campbell had been reading his competition’s magazine, then he would have seen that the feat had already been accomplished.

2. The cat-and-mouse game.

The machinations between murderer Ben Reich and detective Lincoln Powell are interesting to read. To be fair to Campbell, The Demolished Man is a police procedural, but it is not a whodunit, which was probably the type of mystery Campbell was referring to. The Demolished Man is a whydunnit, in that we know from early in the book who will be murdered, who will murder him and how the murder will be accomplished. The motive is murkier, and the denouement finally brings clarity to Ben Reich’s motives. Bester is at his best when he is illuminating the chess moves between Reich and Powell, as Powell tries to uncover means, motive and opportunity, and they both use their considerable syndicates to cherchez la femme, Barbara D’Courtney, the witness to the murder. My favorite piece of writing comes through Bester’s description of this:

Like an anatomical chart of the blood system, colored red for arteries and blue for veins, the underworld and overworld spread their networks. From Guild headquarters the word passed to instructors and students, to their families, to their friends, to their friends’ friends, to casual acquaintances, to strangers met in business. From Quizzard’s Casino the word was passed from croupier to gamblers, to confidence men, to the heavy racketeers, to the light thieves, to hustlers, steerers, and suckers, to the shadowy fringe of the semi-crook and near-honest. (107)

3. Style and Tone.

Style: Postmodern.

When I read Karel Capek’s War with the Newts (1936), I was very surprised that a novel written that early in the twentieth century used postmodern storytelling techniques. It was a pastiche of narrative, academic reports and newspaper clippings. I should have learned my lesson, but I was still surprised by Bester’s use of textual embellishments and linguistic play. He traces the telepathic conversations of the espers through patterns of language, such as spiderwebs, columns, and other abstract designs. I wish that I could reproduce one here. You’ll just have to read the book. Some of his characters’ names emerge through playing with the sounds of symbols, such as @kins, Wyg&, and ¼maine. Bester coins new words and invents slang that always reminds us that we are in a different time and place.

Tone: Hardboiled.

Both protagonist and antagonist have a hard-boiled edge worthy of Hammett or Chandler. Linc Powell’s address to a room full of suspects demonstrates this:

“He paused and lit a cigarette. ‘You all know, of course, I’m a peeper. Probably this fact has alarmed some of you. You imagine that I’m standing here like some mind-peeping monster, probing your mental plumbing. Well… Jo ¼maine wouldn’t let me if I could. And frankly, if I could, I wouldn’t be standing here, I’d be standing on the throne of the universe practically indistinguishable from God. I notice that none of you have commented on that resemblance so far…’” (76).

Also, much of the setting sounds like it is straight from the pen of Raymond Chandler:

Quizzard’s Casino had been cleaned and polished during the afternoon break… the only break in a gambler’s day. The EO and Roulette tables were brushed, the Birdcage sparkled, the Hazard and Bank Crap boards gleamed green and white. In crystal globes, the ivory dice glistened like sugar cubes. On the cashier’s desk, sovereigns, the standard coin of gambling and the underworld, were racked in tempting stacks. Ben Reich sat at the billiard table with Jerry Church and Keno Quizzard, the blind croupier. Quizzard was a giant pulp-like man, fat, with flaming red beard, dead white skin, and malevolent dead white eyes. (94)

A blind, albino croupier. I’m surprised Chandler did not think of him first.

The aspects of The Demolished Man that I liked demonstrate a universalism of tone, style and genre(s) that transcends the time in which the book was written. The aspects that I didn’t enjoy as much relate much more to the date of the book’s creation.

What I didn’t like:

1. Freud.

This book could not have been written without Freudian psychology. The concept of the conscious and unconscious is the basis of Bester’s culture and therefore intrinsic to the book. The espers’ telepathic abilities enable them to probe others’ unconscious thoughts and desires. This facet of Freudian psychology works well and does hold up over time. The Oedipus and Electra Complexes that form other important parts of the plot do not hold up as well and seem clunky in their use. For example, the regressing of Barbara D’Courtney to an infantile mental state so that she can fall in love with her new “daddy,” Linc Powell, seems silly to me:

“’Hello, Papa. I had a bad dream.’

‘I know, baby. I had to give it to you. It was an experiment on that big oaf.’

‘Gimme a kiss.’

He kissed her forehead. ‘You’re growing up fast,’ he smiled. You were just baby talking yesterday.’

‘I’m growing up because you promised to wait for me.’

‘It’s a promise, Barbara.’” (189)

This Electra Complex contributes another theme in the book that I disliked which is the portrayal of women.

2. The portrayal of women.

There are several stereotypical female characters in this book: the madam, the amoral society woman, the smart girl, and the damsel in distress. The two I want to discuss are Mary Noyes, the smart, capable friend of Powell and Barbara D’Courtney, the blonde damsel in distress, who spends most of the book as either an absent object of desire or a grown woman with the mind of a child. Of course, Mary is in love with Linc, and he depends on her for moral and personal support, but he will never love her because she is too smart, too capable; in short, she does not need a “daddy.”

Barbara D’Courtney witnesses her father’s murder and runs away. Reich and Powell search for her though much of the book, and when Powell finds her she can only relive the trauma of her father’s murder. She is then regressed to her infantile stage to heal her. Throughout the book, the reader never sees her make a decision, and she never speaks as an independent being. Lincoln falls in love with a baby in a woman’s body. She, on the other hand, as a victim of the Electra Complex, has no choice but to bond with her daddy. Bester’s Barbara pales in comparison with the women that appear in hard boiled novels, which in and of themselves are not famous for creating positive female role models. At least the femme fatales in Cain, Chandler, and Hammett are tough, strong and get to say some snappy dialogue.

Barbara D’Courtney witnesses her father’s murder and runs away. Reich and Powell search for her though much of the book, and when Powell finds her she can only relive the trauma of her father’s murder. She is then regressed to her infantile stage to heal her. Throughout the book, the reader never sees her make a decision, and she never speaks as an independent being. Lincoln falls in love with a baby in a woman’s body. She, on the other hand, as a victim of the Electra Complex, has no choice but to bond with her daddy. Bester’s Barbara pales in comparison with the women that appear in hard boiled novels, which in and of themselves are not famous for creating positive female role models. At least the femme fatales in Cain, Chandler, and Hammett are tough, strong and get to say some snappy dialogue.

Conclusion:

The Demolished Man is certainly worth the read and not just for its “legacy value.” However, I would like to end with Harry Harrison’s discussion of its legacy:

“This kind of novel had never happened before. Other writers have since used and built upon its structure: Blish, Zelazny, and Delany come to mind. The New Wave mined its assets, and the cyberpunks echo only dim whispers of The Demolished Man’s rolling thunder. But Bester came first—and is still the master.” (From the Introduction, viii-ix).

Outside the Norm: Dubravka Ugresic’s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

I began this Outside the Norm blog because I wanted to challenge myself to read more books by women, persons of color and nationalities other than American and British. So far I’ve read canonical authors like Le Guin and those who are starting to make a name in the F and SF world like Nnedi Okorafor. I’m also beginning to see this title as a license to write about others whose speculative work is just outside the parameters of the lists and awards compiled here. This blog is about one of those books, Dubravka Ugresic‘s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg.

This book first came to my attention because it won the 2010 James Tiptree, Jr. Award. The Tiptree’s mission, as stated on its website, is to honor a science fiction or fantasy work "that expands or explores our understanding of gender" and is given each year at WisCon. Ugresic is a Croatian academic who was forced into exile by a nationalist government. Most of her books and collections of essays are political in nature. This book was nominated for the Man Booker International Prize, so, as you can see, she’s not an author whose name would typically end up on a list of the year’s best fantasy writers. Yet, her use of myth in this book placed the book in the realm of fantasy for some readers like the Tiptree jury. The book is a three-part engagement with Baba Yaga, the witch-like character of Slavic folklore.

I confess that all I really knew about Baba Yaga came through an introduction via the prog rock CD Pictures at an Exhibition (1972) by Emerson, Lake and Palmer. That group had recorded a suite by the Russian composer, Modest Mussorgsky, which Mussorgsky had based on an art exhibition by the Russian artist Viktor Hartmann. (For more about Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, check out the music and new images here.) One of the images that inspired subsequent songs by Mussorgsky and Emerson, Lake, and Palmer was "The Hut of Baba Yaga." This song sent my younger self off to research Baba Yaga.  I learned that Baba Yaga lived in a giant hut that walked around on huge chicken legs. Much like the witches in Grimm’s fairy tales, she lured children to her forest hut and ate them. She flew around in a mortar, using the pestle like an oar, and used a broom to sweep away her tracks. Here you can see her connection to the more western witches on broomsticks. However, no previous knowledge of Baba Yaga is required to read this book because the reader is slowly educated through the author’s three sections. This structure and strategy is what makes this book so interesting and made me decide to write this review.

I learned that Baba Yaga lived in a giant hut that walked around on huge chicken legs. Much like the witches in Grimm’s fairy tales, she lured children to her forest hut and ate them. She flew around in a mortar, using the pestle like an oar, and used a broom to sweep away her tracks. Here you can see her connection to the more western witches on broomsticks. However, no previous knowledge of Baba Yaga is required to read this book because the reader is slowly educated through the author’s three sections. This structure and strategy is what makes this book so interesting and made me decide to write this review.

The short prologue "At First You Don’t See Them…" unapologetically tells the reader that this book will be about old women:

Sweet little old ladies. At first you don’t see them. And then, there they are, on the tram, at the post office, in the shop, at the doctor’s surgery, on the street, there is one, there is another, there is a fourth over there, a fifth, a sixth, how could there be so many of them all at once? (2)

The invisibility of these "little old ladies" is a direct comment on society’s tendency to dismiss the elderly and their needs and forget about their continued usefulness to society. Ugresic’s book goes beyond this generalization of invisibility and takes on the ways that our view of "little old ladies" is often based on gender stereotypes created by earlier patriarchal societies, especially crone figures like the Baba Yaga.

The first section "Go There – I Know Not Where – and Bring Me Back a Thing I Lack" has no speculative fiction elements. It is written in the first person. The narrator is a famous author who frequently returns to her hometown of Zagreb, Croatia to take care of her elderly mother. Her widowed mother has had a stroke: she uses a walker and her language was affected so that she often uses the wrong word. This leads to some humorous conversations between mother and daughter:

The first section "Go There – I Know Not Where – and Bring Me Back a Thing I Lack" has no speculative fiction elements. It is written in the first person. The narrator is a famous author who frequently returns to her hometown of Zagreb, Croatia to take care of her elderly mother. Her widowed mother has had a stroke: she uses a walker and her language was affected so that she often uses the wrong word. This leads to some humorous conversations between mother and daughter:

"Bring me the…."

"What?"

"That stuff you spread on bread."

"Margarine?"

"No."

"Butter?"

"You know it’s been years since I used butter!"

"Well, what then?"

She scowls, her rage mounting at her own helplessness. And then she slyly switches to attack mode.

"Some daughter if you can’t remember the bread spread stuff!"

"Spread? Cheese spread?"

"That’s right, the white stuff," she says, offended, as if she had resolved never to again utter the words ‘cheese spread.’" (11)

I think my favorite one is when she asked for "the biscuits, the congested ones," instead of the digestive ones. (11-12)

We learn that the mother is Bulgarian and came to Croatia as a young wife. Some of her most treasured curios represent Bulgaria or are mementos of her early life. The daughter decides that she wants to visit Bulgaria as her mother’s bedel: "[c]enturies ago the wealthy would send someone else off on the hajj or the army in their stead as a bedel, a paid surrogate" (41). The daughter wants to bring back pictures of her mother’s city so that her mother can remember her youth. She enlists the help of a Bulgarian fan, Aba, who had written the author earlier, wanting to visit her in Croatia. Aba, a student in folklore, was in Croatia on an academic fellowship. The author was unable to meet Aba but facilitated a relationship between her mother and Aba, as fellow Bulgarians. The mother and Aba hit it off, so the daughter later arranges for Aba to accompany her while in Bulgaria. Her best-laid plans of "bedelship" go astray: she finds her mother’s hometown a victim of the communist and post-communist economies and finds the locations of her mother’s home and school changed and worn down; she also finds Aba annoying because the young fan wants to quote the author’s writing back to her. Thus, this first section is a look at aging, relationships and post-communist Eastern Europe.

We learn that the mother is Bulgarian and came to Croatia as a young wife. Some of her most treasured curios represent Bulgaria or are mementos of her early life. The daughter decides that she wants to visit Bulgaria as her mother’s bedel: "[c]enturies ago the wealthy would send someone else off on the hajj or the army in their stead as a bedel, a paid surrogate" (41). The daughter wants to bring back pictures of her mother’s city so that her mother can remember her youth. She enlists the help of a Bulgarian fan, Aba, who had written the author earlier, wanting to visit her in Croatia. Aba, a student in folklore, was in Croatia on an academic fellowship. The author was unable to meet Aba but facilitated a relationship between her mother and Aba, as fellow Bulgarians. The mother and Aba hit it off, so the daughter later arranges for Aba to accompany her while in Bulgaria. Her best-laid plans of "bedelship" go astray: she finds her mother’s hometown a victim of the communist and post-communist economies and finds the locations of her mother’s home and school changed and worn down; she also finds Aba annoying because the young fan wants to quote the author’s writing back to her. Thus, this first section is a look at aging, relationships and post-communist Eastern Europe.

The second section, "Ask Me No Questions and I’ll Tell You No Lies," continues the theme of playing with language that Ugresic began in the first section. One character, Beba, says the wrong word when nervous which leads her to say things like "Have a nice lay," when she means to say "Have a nice day." This playfulness continues throughout section two whose genre is closest to magical realism. It is full of improbable happenings and unbelievable coincidences that the characters never seem to notice. Also all the characters seem more symbolic and less real. Each seems like an archetype for an idea that I don’t quite grasp. (This is not a criticism. I didn’t feel lost at all.)

In this section, three old Croatian ladies, Pupa, Kukla, and Beba, ranging in age from sixty to eighty (or maybe more), visit the Wellness Centre, a spa in the Czech Republic. Their only connection to section one is that Pupa is mentioned there as one of the mother’s friends. Most of the men that the women meet in this section are part of the beauty and anti-aging industry. Mr. Shaker is an American who owns a business that sells pills, potions, and remedies, "bearing the food label supplement" (92). His American market is collapsing because reports are emerging that his remedies "pump up muscles" but "reduced potency" (93). So now he is looking into the "post-communist market" (93). Dr. Topolanek, the owner of the Wellness Centre, makes his living via "human vanity," selling his theory of longevity as well as spa treatments and massages (98). Finally, the old women meet Mevludin, a young Bosnian refugee, who works as a masseur at the Centre. The women spend a fantastic six days at the Centre. The endings are "happy" for Pupa, Kukla, and Beba, but they each travel from the spa into unknown worlds and challenges.

Here Ugresic criticizes the cult of youth and beauty. Her Croatian perspective is interesting because in Eastern Europe this cult is directly tied to post-communist capitalism. Dr. Topolanek sees his generation’s revolution as an internal one, one that allows people to change their bodies to whatever they want them to be. One of the best moments of this section shows Beba, who has been portrayed as an airhead up to this point, relaxing in a bath of warm chocolate (one of the therapeutic treatments) and musing upon the reproduction of Renior’s Woman with Parrot, hung on the wall. Beba’s thoughts carry us through an art history lecture that connects parrots with women’s sexuality in western art. This is a fun (and unexpected) tangent, but again illustrates why the book appealed to the Tiptree jury.

Here Ugresic criticizes the cult of youth and beauty. Her Croatian perspective is interesting because in Eastern Europe this cult is directly tied to post-communist capitalism. Dr. Topolanek sees his generation’s revolution as an internal one, one that allows people to change their bodies to whatever they want them to be. One of the best moments of this section shows Beba, who has been portrayed as an airhead up to this point, relaxing in a bath of warm chocolate (one of the therapeutic treatments) and musing upon the reproduction of Renior’s Woman with Parrot, hung on the wall. Beba’s thoughts carry us through an art history lecture that connects parrots with women’s sexuality in western art. This is a fun (and unexpected) tangent, but again illustrates why the book appealed to the Tiptree jury.

The third section continues on this scholarly tone. It begins with a letter that Dr. Aba Bagay, presumably the Bulgarian folklore student in section one, writes to an unknown editor who has asked her to read a manuscript and "explicate the correspondences between [the] author’s text and the myth of Baba Yaga" (239). The remainder of the section is her response, "Baba Yaga for Beginners," which discusses symbols related to Baba Yaga, supporting these with quotations from Eastern European myths and legends as well as quotations from scholars in the field, such as Maria Gimbutas and Marina Warner. Aba includes discussions of Baba Yaga’s name, her connection with witches and cannibalism and all her symbols, such as the hut, the mortar and pestle, birds and eggs. After each part, Aba provides "Remarks" that analyze the fictional author’s text in reference to the topic she just explained.

The surprising part is that the text that Aba is reading and commenting upon is made up of the two sections we just read. So, effectively, we have an author in the guise of an academic analyzing the book she just wrote. Ugresic shows her readers all of the Baba Yaga symbols and allusions that she included and they missed (at least many were missed on my part). For example, following her discussion of the hut, Aba writes:

Returning home, your author returns to the maternal ‘hut’ and repeats the initiation rite for the nth time. She must respect the law of Baba Yaga’s hut, otherwise Baba Yaga will eat her up. (263)

I’ve tried to find some other examples, but many of them give away too much about the plot. Just trust me; I couldn’t wait to finish each part so that Aba could connect my new knowledge of Baba Yaga to the previous plots. This set up makes for a very rich reading experience. I’ve never read a book before that taught its readers how to read it. I enjoyed being educated about the myth of Baba Yaga in this unorthodox manner.

I’ve tried to find some other examples, but many of them give away too much about the plot. Just trust me; I couldn’t wait to finish each part so that Aba could connect my new knowledge of Baba Yaga to the previous plots. This set up makes for a very rich reading experience. I’ve never read a book before that taught its readers how to read it. I enjoyed being educated about the myth of Baba Yaga in this unorthodox manner.

The ending brings in an element of the supernatural and that, along with the heavy dose of myths and folklore in section three and the magical realism of section two, shows me why this book was nominated for and won the Tiptree Award, even though at first glance this is not an obvious candidate. I found this book a very pleasurable read because I was continually intrigued about the way the story was being told.

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm.

I love the 80s and not just on VH1

Ready Player One is a fantastic book that finds a way to do something really interesting with nostalgia. The setting is the bleak future, a time of gas shortages, which have led to the collapse of suburbia. In 2044 the slums have become “stacks,” trailer parks with trailers stacked twenty or thirty high. The cities grow upward because the lack of gas means they cannot grow out. The only leisure activity in this new landscape is a virtual world called the OASIS, “a sprawling virtual utopia that lets you be anything you want to be, a place where you can live and play and fall in love on any of ten thousand planets” (from the blurb). Membership for OASIS is free, all one needs is a computer, a visor and haptic gloves, all of which seem to be affordable in this world. Much of this virtual society is free for anyone to use and enjoy; however, real money equals virtual credits, which allows the rich to travel far and wide in OASIS, build homes and purchase all of the virtual creature “comforts,” including weapons, armor and space ships. The poor, however, can use the virtual equivalent of mass transportation to participate in all sorts of free experiences and adventures and enjoy themselves as well. This world seems to be the SIMs plus Second Life plus World of Warcraft.

The protagonist Wade Watts is an orphan living in the stacks with an aunt who only values him for the extra food vouchers his presence brings. He lives with her and thirteen other occupants in a double-wide trailer near the top of their stack. Like most teenaged boys, Wade has found himself a hideout, a hidden van, long abandoned by its owner, that he uses to avoid his home life. He only enters the trailer when the weather is too cold for him to stay in the van. While Wade lives a life of poverty, he is able to receive a good education via the OASIS public school system. Wade’s avatar attends one of the thousands of identical schools on the virtual planet Ludus. He takes classes lead by teacher avatars who are able to use the educational power of the virtual worlds to take the students on field trips anywhere in time or space.

Wade is sure he is destined to be one of the many unemployed when he graduates high school. Then, the creator of OASIS, James Halliday, dies, and his avatar, Anorak, announces that his billions will be won by the person who can complete his contest, quickly dubbed the Hunt (i.e., the hunt for the Easter Eggs Halliday built into the OASIS programming). The clues and puzzles are scattered throughout this virtual world. Wade, along with every other person in the world, sees this as his opportunity to escape poverty. The catch is that Halliday was a teenager in the 1980s and for his whole life has been a collector of 1980s movies, music, TV shows and games. His love for pop culture continued throughout the 20th century. The Hunt will test the gunters’ skill in trivia and gaming–gunters, a portmanteau word for egg hunter. A good clue to gunter culture comes through their recommended reading list: “Douglas Adams, Kurt Vonnegut, Neal Stephenson, Richard K. Morgan, Stephen King, Orson Scott Card, Terry Pratchett, Terry Brooks, Bester, Bradbury, Haldeman, Heinlein, Tolkien, Vance, Gibson, Gaiman, Sterling, Moorcock, Scalzi, Zelazny” (62).

In the opening of Ready Player One, the Hunt has been going on for five years, and not one aspirant has scored a point on the big scoreboard; Wade is 18 years old and has spent the past five years immersing himself in the 1980s: “That was what saved me, I think. Suddenly I’d found something worth doing. A dream worth chasing. For the last five years, the Hunt had given me a goal and a purpose. A quest to fulfill. A reason to get up in the morning” (19). He can manage high scores in video games like Joust and Donkey Kong, and he knows all the dialogue of Back to the Future and all the 80s “classics.” Wade, in the form of his OASIS avavtar, Parzival, has a virtual best-friend, Aech, and a virtual crush on a gunter blogger, Art3mis. He hangs out in Aech’s Basement, a chatroom “programmed… to look like a large suburban rec room…. Old movie and comic book posters covered the wood-paneled walls. A vintage RCA television stood in the center of the room, hooked up to a Betamax VCR, a LaserDisc player, and several vintage videogame consoles” (37). Here Aech and Parzival argue about which movie is better, Legend, Labyrinth or Ladyhawke and other issues that should’ve left social conversations before their parents were born.

Wade finally figures out Halliday’s first clue one day in Latin class, locates the first Easter Egg, and beats the first Boss. Within a day, Parzival is famous. The name tops the scoreboard, and he has made some real money endorsing gunter products as Parzival (without him giving out his real identity.) Of course, there’s an evil empire that wants to force him to reveal the first location—this is really just a quest myth after all, so there has to be an evil empire. In the first part of the book, almost all the action takes place in the virtual world with Wade holed up in his hideout and Parzival participating in the Hunt. In the latter part, Wade is under threat so there’s more of a mixture of real world and virtual action. I don’t really read cyberpunk, so I found it interesting that I was so enthralled by a book in which the protagonist is sitting in a room for its majority.

Wade finally figures out Halliday’s first clue one day in Latin class, locates the first Easter Egg, and beats the first Boss. Within a day, Parzival is famous. The name tops the scoreboard, and he has made some real money endorsing gunter products as Parzival (without him giving out his real identity.) Of course, there’s an evil empire that wants to force him to reveal the first location—this is really just a quest myth after all, so there has to be an evil empire. In the first part of the book, almost all the action takes place in the virtual world with Wade holed up in his hideout and Parzival participating in the Hunt. In the latter part, Wade is under threat so there’s more of a mixture of real world and virtual action. I don’t really read cyberpunk, so I found it interesting that I was so enthralled by a book in which the protagonist is sitting in a room for its majority.

Admittedly, I am in the correct age demographic to get all of Ernest Cline’s 80s references, and although I did not play all of the video games that litter its pages, I spent enough time in arcades to understand the lifestyle that Parzival emulates in his cyberworld. There’s a two-page riff that Wade does describing his self-education, in which he “learned the name of every goddamn Gobot and Transformer” (63) that is absolutely hilarious to anyone who grew up in the 80s. As Parzival goes about his business in the OASIS, Cline provides Wade with lines and an interior dialogue straight from movies (often unidentified). The one that made me laugh out loud is Wade’s spoken pass phrase that enables him to login to OASIS: “You have been recruited by the Star League to defend the frontier against Xur and the Ko-Dan armada” (26). This book offers some interesting parallels to The Last Starfighter, which makes this reference all the more fun.

Cline’s book is a very successful attempt to translate a video game to a written form. Anyone who has played NES games like the Zelda series will recognize all the beats of Parzival’s quest. And those of us who have some 80s knowledge try to figure out the clues before he does (I never did, which made me like this book all the more fun). It is no secret at this point in my review that I loved this book. In fact, writing this review is making me want to read it again, but I’m going to resist… for a while. However, one of the messages of this book is that it’s no shame to geek out over the pop culture we love. After all, Wade watched Monty Python and the Holy Grail 157 times.

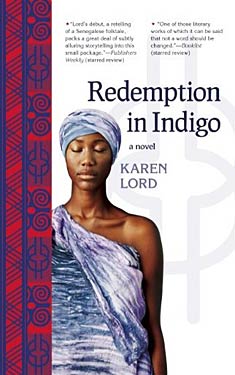

Outside the Norm: Karen Lord’s Redemption in Indigo

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

Nalo Hopkinson calls Karen Lord‘s Redemption in Indigo "[t]he impish love child of Tutuola and Garcia Marquez." I have never read Tutuola, but I immediately understood Hopkinson’s comment when I started reading the book and thought it was a mixture of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. So, no matter what authors or book the readers use for their analogies, the most compelling feature of Redemption in Indigo is its ability to mix New World magical realism with Old African folktales, in her case the world of Barbados and its undying spirits, the djombi, with the Senegalese folktales of Anansi, the spider trickster god.

Nalo Hopkinson calls Karen Lord‘s Redemption in Indigo "[t]he impish love child of Tutuola and Garcia Marquez." I have never read Tutuola, but I immediately understood Hopkinson’s comment when I started reading the book and thought it was a mixture of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. So, no matter what authors or book the readers use for their analogies, the most compelling feature of Redemption in Indigo is its ability to mix New World magical realism with Old African folktales, in her case the world of Barbados and its undying spirits, the djombi, with the Senegalese folktales of Anansi, the spider trickster god.

The book begins by setting up the narrative as a tale told by a storyteller: an "I" who is talking to a group of "yous," of which the reader is one. The story playfully ends with the storyteller’s solicitations:

"it is terribly dry and thirsty work, speaking these lives into the dusty air of the court, speaking for you to hear and ponder and judge. Perhaps, if you would be so kind as to contribute, I could purchase some refreshments now, find a place to rest my head later, and return to you on the morrow with my voice and memory and strength restored. Please, ladies and gentlemen, if you have at all enjoyed my story, be generous as the pot goes around, and do come back again soon." (182)

He similarly begins the epilogue by telling us that he has been "authorised" to tell us more. This narrative method enhances the folktale elements because it provides an inventive way to fill in cultural background for readers who probably aren’t familiar with the ways of the greater and lesser djombi and the other supernatural beings they encounter.

Our storyteller begins with the story of Paama, who’s left her husband, Ansige, and returned with her family to her village. Paama leaves her husband because of his gluttony. He was "not an epicure, but a gourmand," his every thought and action controlled by his desire for food and his only worry about his next meal (7). When Ansige finally arrives at the village to beg her to return to him, his exploits demonstrate his origin in East African folktale characters. His gluttony gets him into all kinds of trouble from which Paama has to rescue him. However, Paama has bigger problems than her husband. Before Ansige even arrives at her village, two djombi have decided to steal Chaos from another djombi and give it to Paama, which will give her immense power. Just as Paama starts to understand her unwanted power, the indigo djombi, the original wielder of Chaos, has tracked his power to her village.

The relationships Lord forges between the supernatural beings and humanity elevate the plot beyond the typical tale of a heroine who must fight to save her people and their way of life. The supernatural beings are complex characters who are dissatisfied with the way their identities often limit their roles. The storyteller speaks about the indigo djombi:

The djombi are like the human creatures they meddle with, apt either to great evil or great good, and sometimes they switch sides.

This one was the unknown danger. He had switched sides. He had started with benevolence, with the belief that there is the fine potential in humankind waiting only to be tapped. He now viewed the whole stinking breed as a pest and a plague. (58)

As a symbol of his change from benevolent to malignant, the djombi changes his color to indigo, "a stark and utter setting apart that provoked as much of horror as of awe" (59). Another supernatural being, the Trickster, who usually appears in the form of a spider, changes in the opposite direction. He began "delighting in the frailties of humans and exploiting those weaknesses for his own entertainment" but became bored with "playing the same old practical jokes" (102). After a while he started "turning people to situations of mutual benefit rather than merely gratifying his own sense of the ridiculous" (102). The pleasure in this novel is observing these beings as they learn about their omnipotence and start to interact with Paama and her community in a meaningful way. The ending, while somewhat predictable, gives the readers the happy endings and the redemptions that the title tells them to expect.

As a symbol of his change from benevolent to malignant, the djombi changes his color to indigo, "a stark and utter setting apart that provoked as much of horror as of awe" (59). Another supernatural being, the Trickster, who usually appears in the form of a spider, changes in the opposite direction. He began "delighting in the frailties of humans and exploiting those weaknesses for his own entertainment" but became bored with "playing the same old practical jokes" (102). After a while he started "turning people to situations of mutual benefit rather than merely gratifying his own sense of the ridiculous" (102). The pleasure in this novel is observing these beings as they learn about their omnipotence and start to interact with Paama and her community in a meaningful way. The ending, while somewhat predictable, gives the readers the happy endings and the redemptions that the title tells them to expect.

Because Karen Lord explores these big ideas of omnipotence and redemption in a Caribbean setting, her book has garnered attention outside the F/SF community. It won the 2008 Frank Collymore Award, given to an unpublished Barbadian work. It was also nominated for the 2011 Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. Back in the F/SF world, the book was a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and won the 2011 Mythopoetic Award and the 2011 Crawford Award for the best fantasy novel by a new writer. For more on its awards, see Karen Lord’s interview with Chesya Burke.

The adjective that comes to mind when I think about Redemption in Indigo is fresh. The story has recognizable elements–heroes, gods meddling with the affairs with humans, mythological characters and folktales–but Lord uses these elements in unexpected ways, except for the ending, which is satisfying in its predictability. Her style of fantasy is smart, inventive, and innovative. I look forward to Lord’s next book.

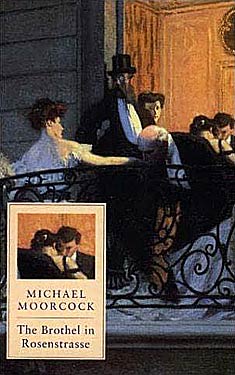

GMRC Review: The Brothel in Rosenstrasse by Michael Moorcock

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fifth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fifth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

In my attempt to combine some of my reading challenges, I decided to read Michael Moorcock‘s The Brothel in Rosenstrasse for the GMRC. The "brothel" in the title fulfills the "house" requirement in Beth Fish’s Readers Challenge. Before I chose this book, I did a little research and learned that the book was the second in Moorcock’s Rickhardt von Bek trilogy but that I need not read the first book before reading the second.

In my attempt to combine some of my reading challenges, I decided to read Michael Moorcock‘s The Brothel in Rosenstrasse for the GMRC. The "brothel" in the title fulfills the "house" requirement in Beth Fish’s Readers Challenge. Before I chose this book, I did a little research and learned that the book was the second in Moorcock’s Rickhardt von Bek trilogy but that I need not read the first book before reading the second.

Von Bek is the first person narrator of the novel. As a sick, bedridden old man, von Bek writes a memoir about his secret affair with the sixteen-year-old, Alexandra, a daughter of a noble family. This affair took place in fin de siècle Mirenburg, a city located in the fictional central European nation of Waldenstein. Moorcock creates a lush, cosmopolitan, multicultural city, where Europeans come to enjoy the cafés, cabarets, opium dens, and, of course, the brothel, "Mirenburg’s greatest treasure," "protected by every authority and tolerated by the Church" (45). Unfortunately, the architectural beauty and joie de vivre of Mirenburg is destroyed by a civil war during the course of the book.

Before the war comes, Alexandra and von Bek live together in the Liverpool Hotel and take advantage of the lax stewardship of Alexandra’s parents (who are out of the country), her aunt (who is supposed to be responsible for Alexandra in their absence but farms her off to the housekeeper, who is tricked by her charge). Von Beck is infatuated by Alexandra but is also repulsed by her extreme willingness to play the role of his sex toy. He justifies his lifestyle as a debaucher and rake by writing "I live as I do because I have no need to work and no great talent for art; therefore my explorations are usually in the realm of human experience, specifically sexual experience, though I understand the dangers of self-involvement in this as in any other activity" (94). In order to keep his pupil Alexandra interested, von Beck begins taking Alexandra to the brothel, where they engage in threesomes, foursomes, sadomasochism and cocaine use.

When the war comes, Alexandra tells her family that she and her friends are joining refugees outside the city but instead she and von Bek are forced to seek refuge in the brothel once their hotel is bombed. Von Bek describes the brothel as "an integrated nation, hermetic, microcosmic" (49). However, while von Bek enjoys the clubby atmosphere of the salon and the dining table, Alexandra must hide in their room because they cannot risk her being recognized by another member of the nobility. Once von Beck relents and lets Alexandra appear, she begins to manipulate the citizens of the microcosm as the long siege of Mirenburg begins.

Von Bek’s memoir slips between his past in Mirenburg and his present as an invalid whose only human contact is with his manservant. Moorcock handles this in an interesting way as von Bek’s arguments (both vocal and silent) with the manservant Papadakis weave in and out of the memoir:

I can only admit now that I gave myself up to Eros deliberately, in the belief it does a man or woman good to make such fools of themselves occasionally, there are few risks much wilder and few which make us so much wiser, should we survive them. Papadakis stretches out his emaciated arms. I smell boiled fish. "It will do you good," he says in his half-humorous, half-insinuating voice; a voice once calculated during his own, brief Golden Age to rob the weak of any volition they might possess; but it had been the single weapon in his arsenal; he had used up all of his emotional capital by the time he was forty. (38)

Von Bek’s writing demonstrates his insecurity concerning Alexandra in the past and his fear of death in the present. The narrative has the fury of a man writing against time and to regain his past. He alternates between scenes of sexual excess and lush description that shows his love of Mirenburg, which he loves as much as Alexandra.

Von Bek’s writing demonstrates his insecurity concerning Alexandra in the past and his fear of death in the present. The narrative has the fury of a man writing against time and to regain his past. He alternates between scenes of sexual excess and lush description that shows his love of Mirenburg, which he loves as much as Alexandra.

There are no fantasy or supernatural elements in this book. Only Moorcock’s name and the fact that Rickhardt von Bek’s ancestor Ulrich is the protagonist of The War Hound and the World’s Pain connect The Brothel in Rosenstrasse to the fantasy genre; this book is a historical romance focusing on decadence and obsession. Unless WWE readers are also interested in historical fiction, I’d recommend this one for Moorcock completists only. The plot is thin, and the characters are weak and not really likeable. The city of Mirenburg is the star: the descriptions of the city are beautiful and his ability to situate the reader in a location is dazzling. I am looking forward to reading the other two books in the series but hope they are more driven by character and plot.

Moorcock has made his fictional brothel famous not only through the book but through song. The song was recorded by Michael Moorcock and Deep Fix in 1982. You can hear it on YouTube.

The lyrics are as follows:

Schmetterling says that all her girls are ladies

She won’t hand out keys to anyone who’s shady

It’s all done with taste, you must not seem a waster or a scoundrel

She’s kind and she’s warm, believes in good form

So don’t be hasty!The Brothel in Rosenstrasse all our girls are clean and game

The Brothel in Rosenstrasse, you don’t have to give your right namePlease don’t speak of despair, or anything that’s seedy

Please don’t admit you’re cynical and greedy

Your manner’s refined, your role is clearly defined, and so is the lady’s

The things that you do aren’t wicked or rude, because you need themThe Brothel in Rosenstrasse, all our girls are keen to please

The Brothel in Rosenstrasse, at reasonable fees

GMRC Review: The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fourth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fourth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Many of the GMRC reviewers have noted that some books seem very much of their times. In fact, I commented in my review of Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun that several of his stories seemed dated. In reference to Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest, no observation could be more untrue. The novella upon which the novel is based won both the Nebula and Hugo Awards in 1973. The novella appeared in Harlan Ellison’s second New Wave anthology Again, Dangerous Visions in 1972. Le Guin published the novel version in 1976. However, with its focus on ethnic and ecological concerns, it seems as if it could have been written last year.

Many of the GMRC reviewers have noted that some books seem very much of their times. In fact, I commented in my review of Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun that several of his stories seemed dated. In reference to Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest, no observation could be more untrue. The novella upon which the novel is based won both the Nebula and Hugo Awards in 1973. The novella appeared in Harlan Ellison’s second New Wave anthology Again, Dangerous Visions in 1972. Le Guin published the novel version in 1976. However, with its focus on ethnic and ecological concerns, it seems as if it could have been written last year.

The novel takes place in New Tahiti Colony, on the planet Athshe. Terran workers have come to this tree-covered planet to harvest the trees and return them to Earth, which is mostly barren. In comparison, “New Tahiti was mostly water, warm shallow seas broken here and there by the reefs, islets, archipelagoes, and the five big Lands that lay in a 2500-kilo arc across the Northwest Quarter-sphere. And all those flecks and blobs of land were covered with trees. Ocean: forest. That was your choice on New Tahiti. Water and sunlight, or darkness and leaves” (15-16). Because this is one of Le Guin’s Hainish novels, the planet’s population was seeded by the Hains centuries earlier. The indigenous population are, of course, forest dwellers, but they took a very different evolutionary turn than their “cousins” the Terrans. The Athsheans are about a meter high with green fur. They look much like monkeys. The Athsheans have complex sleeping patterns, which involve multiple “naps” and lucid dreaming. The Terrans misinterpret the Athsheans’ biorhythms. At first they think that the Athsheans will make good slaves or members of the Voluntary Autochthonous Labor Corps (their euphemism) because they don’t sleep. Later the Terrans think that the Athsheans are lazy because they don’t realize that their “Voluntary Autochthonous Laborers” are napping rather than just sitting still and staring into space. This behavior leads the Terrans using verbal and physical violence to make their workers “productive.”

One of the best “motivators,” in his opinion, is Captain Don Davidson. He is one of the workers at the logging camp and is one of the of the three point of view characters in the novel. The second is Selver, a former Athshean slave who attacked Davison and then was allowed to escape by Captain Raj Lyubov, who is an anthropologist and the third point of view character. Davidson demonstrates the callous attitude towards nature that caused his Earth to become barren. He calls the indigenous population “creechies” and hunts the animals on the planet for sport. He sees himself as “a world-tamer”: (14). He thinks “it’s Man that wins, every time. The Old Conquistador” (15). Selver is not “a world-tamer” but “a world-changer.” He learns violence from the Terrans and teaches the Athsheans how to attack in order to save themselves and their world from the colonizing Terrans: “Selver had brought a new word into the language of his people. He had done a new deed. The word, the deed, murder” (124). Lyubov is the tragic middle man. He understands both cultures and sees each culture’s inability to interpret the other. The Terrans are too greedy and too stubborn to attempt to understand the “humanity” of the Athsheans, while the Athsheans, as the weaker colonized people, quickly decide that they must adopt the violent ways of the humans if they want to keep their world.

This book is the perfect marriage of Le Guin’s interests in anthropology and ecology as well as her penchant for standing up and speaking out. In her introduction to the book, reprinted in The Language of the Night, Le Guin tells us that she wrote the novella in “pursuit of freedom” … but “succumbed, in part, to the lure of the pulpit” (151). She further describes her protests against the Viet Nam War during 1968. This text illustrates her frustration with the war itself but also with the amount of collateral damage the fighting caused to the Vietnamese eco-system and the non-combatants. Her motives were transparent then and have remained so over the years. For example, the book appears beside a bed in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket as a telling anachronism. The irony is: even though the book was partially engendered by one of the most significant events in the late twentieth century and even though Le Guin’s ex post facto introduction almost apologizes for its proselytizing tone, the book still speaks to the world of the twenty first century. In many ways this is unfortunate because this means there are still Don Davidsons in the world.

This book is the perfect marriage of Le Guin’s interests in anthropology and ecology as well as her penchant for standing up and speaking out. In her introduction to the book, reprinted in The Language of the Night, Le Guin tells us that she wrote the novella in “pursuit of freedom” … but “succumbed, in part, to the lure of the pulpit” (151). She further describes her protests against the Viet Nam War during 1968. This text illustrates her frustration with the war itself but also with the amount of collateral damage the fighting caused to the Vietnamese eco-system and the non-combatants. Her motives were transparent then and have remained so over the years. For example, the book appears beside a bed in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket as a telling anachronism. The irony is: even though the book was partially engendered by one of the most significant events in the late twentieth century and even though Le Guin’s ex post facto introduction almost apologizes for its proselytizing tone, the book still speaks to the world of the twenty first century. In many ways this is unfortunate because this means there are still Don Davidsons in the world.

I recommend the book highly. It is a quick read that will make you consider humanity in many of its lovely and gruesome forms. Le Guin gets the last word about this classic: “The work must stand or fall on whatever elements it preserved of the yearning that underlies all specific outrage and protest, whatever tentative outreaching it made, amidst anger and despair, toward justice, or wit, or grace, or liberty” (The Language of the Night 152).

Full Details

Full Details