GMRC Review: Prelude to Space by Arthur C. Clarke

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his second for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his second for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Prelude to Space by Arthur C. Clarke is my second read in the 2012 WWEnd Grand Master Reading Challenge. Last month I read Poul Anderson‘s Tau Zero (1970), which is one Anderson’s better known novels. For my second read I picked something a little less high profile. Prelude to Space is the first novel Arthur C. Clarke wrote and is generally not considered as good as Childhood’s End (1953), probably the most famous of Clarke’s early novels. The publication history of this story is not unusual for the period. Clarke wrote the novel in the space of a month in 1947 but it wasn’t until 1951 that the whole novel was published in magazine format by Galaxy Science Fiction. It was followed by a hardcover edition in 1953. What is atypical about it, is that the novel does not appear to be based on one of Clarke’s short stories. Although one of Clarke’s lesser works, it has been reprinted numerous times. The edition I have read was printed in 1977 and includes a "Post Apollo Preface", as Clarke himself puts it, written in 1969.

Prelude to Space by Arthur C. Clarke is my second read in the 2012 WWEnd Grand Master Reading Challenge. Last month I read Poul Anderson‘s Tau Zero (1970), which is one Anderson’s better known novels. For my second read I picked something a little less high profile. Prelude to Space is the first novel Arthur C. Clarke wrote and is generally not considered as good as Childhood’s End (1953), probably the most famous of Clarke’s early novels. The publication history of this story is not unusual for the period. Clarke wrote the novel in the space of a month in 1947 but it wasn’t until 1951 that the whole novel was published in magazine format by Galaxy Science Fiction. It was followed by a hardcover edition in 1953. What is atypical about it, is that the novel does not appear to be based on one of Clarke’s short stories. Although one of Clarke’s lesser works, it has been reprinted numerous times. The edition I have read was printed in 1977 and includes a "Post Apollo Preface", as Clarke himself puts it, written in 1969.

In the year 1978 humanity is ready to for the next step in exploration, the first manned mission to the Moon is about to leave Earth. Historian Drik Alexson is sent to London, where the headquarters of Interplanetary, the non-profit organization coordinating the mission, is located. He is to document the event, that will no doubt be considered one of the turning points in human history. Although Alexson is supposed to be an impartial observer, he can’t help but by swept away by the magnitude of the effort and the impact it will have on human society. As the launch date nears, Alexson realizes that this event will be his life’s work as a historian.

Although science fiction is much more about exploring ideas and what they might mean to society than actually predicting the future, seeing how many details Clarke got wrong in this novel is still almost as interesting as the story itself. Where Clarke goes for private enterprise as the driving factor and assumes the memory of the Second World War will change the way people see armed conflict, in reality is was the tension between East and West that gave space exploration a huge boost. The need for the US to prove it could outdo their Soviet rivals resulted in a moon landing nine years before the one Clarke describes, using very different rockets to get there. Many of Clarke’s novels describe futures where science, logic and reason triumph over the petty squabbles, religious dogmas and ideological differences to achieve a peaceful and stable way of running the planet. In Prelude to Space this is treated as inevitable. Would that Clarke had been right on that point.

Another thing that struck me about Clarke’s scenario is the use of atomic energy to power these rockets. These days, radioactivity makes people very nervous, and rightly so as recent events in Fukushima have shown us. Some horrendous experiments were carried out testing nuclear devices in the 1950s, clearly showing that the long term impact of radioactive substances released into he environment was still very poorly understood at the time this novel was written. The radioactivity around the launch site in the Australian desert is mentioned several times but not considered a matter of great concern. It might be technically possible to limit the risk of radioactive contamination, even in the event of a launch failure, but somehow I think it would be very hard to convince the general public that it’d be safe these days.

Clarke’s futures are generally pretty optimistic, sometimes even utopian, and this novel is no exception. Prelude to Space is something of a cross between a love letter to and an advertisement for space exploration. Clarke carefully connects the historical desire to travel to the stars, early science fiction and lots of technological developments, all leading to this one momentous occasion. The moment when humanity will finally leave its cradle and first set foot on a strange world. A first step on a path from which there will be no turning back. Where that path will lead, Clarke doesn’t dare predict but he seems to be quite sure it is one we must take to ensure survival of the species. The author may overdo it a little in the text but his enthusiasm is contagious. It was almost enough to make me wonder why the hell we are not on our way to Mars already.

Clarke’s futures are generally pretty optimistic, sometimes even utopian, and this novel is no exception. Prelude to Space is something of a cross between a love letter to and an advertisement for space exploration. Clarke carefully connects the historical desire to travel to the stars, early science fiction and lots of technological developments, all leading to this one momentous occasion. The moment when humanity will finally leave its cradle and first set foot on a strange world. A first step on a path from which there will be no turning back. Where that path will lead, Clarke doesn’t dare predict but he seems to be quite sure it is one we must take to ensure survival of the species. The author may overdo it a little in the text but his enthusiasm is contagious. It was almost enough to make me wonder why the hell we are not on our way to Mars already.

This is the tenth novel by Clarke I have read, spanning his entire career, and from those it seems obvious that Clarke didn’t change his approach to writing a whole lot during his seven decades as a published author. Some sections of the novel are highly technical, with the science of space travel the main character. Alexson is the vehicle that allows Clarke to show the events leading up to the launch from up close, but he seems to have very little interest in the man himself (perhaps not altogether surprising, he strikes me as a bright but not very interesting fellow). You don’t read Clarke for his well rounded characters or complex plots but for the hard science and Clarke’s visions of what they may mean for future society.

Sixty-five years after it was written Prelude to Space is badly dated in just about every aspect of the story. From the technical developments to the blatant sexism that plagued science fiction in those days. On top of that, Clarke wrote a novel that reads like propaganda for a space program. It is very effective propaganda though. Despite all the novel’s flaws, you can’t help but be caught up in the excitement of the enterprise and the possibilities of space travel, many of which still haven’t been realized. Clarke’s optimism has been proven unfounded in some ways but the drive to explore space is still there. This novel might well have been an inspiration to some teenager in the 1950s to pursue a career in physics or astronomy. Clarke has gone on to write more challenging novels but for a debut, it’s a decent read.

GMRC Review: Tau Zero by Poul Anderson

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his first for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his first for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Note: There be spoilers here!

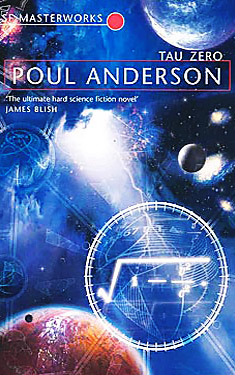

I decided to sign up for the 2012 Grand Master Reading Challenge, organized by World Without End. The goal is to read and review a work by a different Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award winner every month. I decided to start with Poul Anderson, who was honoured with the award in 1998. Tau Zero (1970) is one of his better known works. It was nominated for the Hugo Award in 1971 but lost to Larry Niven‘s Ringworld. It is a very good example of hard science fiction, written in a time when the direction of the genre was being drastically changed by the arrival of new age authors. The novel is an expansion of the short story To Outlive Eternity which was first published in Galaxy Science Fiction in 1967. I’m not going to hold back on spoilers in this review, the title of the short story gives is one already anyway. You have been warned.

I decided to sign up for the 2012 Grand Master Reading Challenge, organized by World Without End. The goal is to read and review a work by a different Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award winner every month. I decided to start with Poul Anderson, who was honoured with the award in 1998. Tau Zero (1970) is one of his better known works. It was nominated for the Hugo Award in 1971 but lost to Larry Niven‘s Ringworld. It is a very good example of hard science fiction, written in a time when the direction of the genre was being drastically changed by the arrival of new age authors. The novel is an expansion of the short story To Outlive Eternity which was first published in Galaxy Science Fiction in 1967. I’m not going to hold back on spoilers in this review, the title of the short story gives is one already anyway. You have been warned.

Fifty men and women are sent on the spaceship Leonora Christine to explore and, if possible, colonize a planet more than thirty light years away. To make the trip in a reasonable span of time, the spaceship has to approach the speed of light and make use of the time dilation effects that become appreciable at such speeds. Before deceleration can be set in, the engines needed to slow down the ship are severely damaged. Repairing them would mean shutting the acceleration engines off as well, which would result in a quick death from intense radiation. The ship’s speeds keeps increasing, hurling the crew ever faster through space and time. Unless they can find a way to slow down the crew is doomed to live out their life on board the space ship.

Tau Zero is science fiction so hard it cuts diamonds. A physics lesson and a novel rolled into one. The publisher kindly provided the formula for the time contraction factor Tau, which equals the square root of 1 minus v squared divided c squared, where v stand for velocity and the constant c is the speed of light. In other words Tau equals zero when v equals c (everybody still with me?). In a more practical sense, the closer the speed of the ship gets to the speed of light, the larger the difference between time passing for the crew and time passing outside the ship. I understand that Anderson’s use of Tau is a bit unorthodox but for narrative purposes it serves very well.

In a way, Anderson uses Tau to show us just how large the universe really is, something he is rather fond of doing in his other science fiction novels as well. As the velocity of the ship approaches the speed of light, minutes, hours, days, years and eventually aeons pass for every second of ship time. Galaxies are crossed, then clusters and super clusters to the point where time and distance becomes meaningless. In the end, Anderson takes us to the death of the universe itself and there a bit of speculation seeps in. The debate about the eventual fate of the universe is still raging, Anderson assumes the universe is cyclic and will eventually contract into a new singularity and expand again after a big bang. Although science has not come up with the proof for this yet, in literature the death and rebirth of the universe does make for a wonderful theme.

That’s quite a lot of physics and cosmology for the reader to take in. The more experience science fiction reader will have come across these elements before. Alastair Reynolds for instance, includes much more exotic science into his works. Anderson explains the physics clearly, even the more counter intuitive elements of relativity, but spares us quantum mechanics. Personally, I enjoyed the scientific passages a lot. That is my personal taste however; it will no doubt put some readers to sleep in a few pages. This novel requires some interest in physics and cosmology to really appreciate.

One might think that this would be enough science for a single novel but Anderson also throws in quite a lot of detail about the Bussard engine of the spaceship. This theoretical way of propelling a ship was first proposed in 1960 and has appeared in a number of science fiction novels by such authors as Larry Niven and Carl Sagan. It is basically a fusion engine which uses the minute quantities of free hydrogen in space to propel the ship. There has been a lot of debate about whether or not a ship powered in such a way would actually be able to reach relativistic speeds, but it’s an ingenious idea anyway. Again Anderson explains the design of the engine and its limitations, which play a large part in the efforts to slow the ship down, very clearly. I thought the engineering was a bit less interesting than the cosmology but it is central to the plot and Anderson makes sure not to overdo it.

Hard science fiction has a reputation of paying less attention to character and character development. For Tau Zero that is definitely true. I guess you could consider the two people we meet in the opening chapter, the compassionate Ingrid Lindgren and the brusque Charles Reymont to be the main characters. They appear to be the people who keep the crew together and sane as Earth becomes an ever more distant memory. They are mostly people dealing with problems of the crew’s morale and organizing efforts to solve their technical problems. Although towards the end of the book things get a bit more philosophical (the death and rebirth theme does have an effect on them), there is very little in the way of development in their characters.

Hard science fiction has a reputation of paying less attention to character and character development. For Tau Zero that is definitely true. I guess you could consider the two people we meet in the opening chapter, the compassionate Ingrid Lindgren and the brusque Charles Reymont to be the main characters. They appear to be the people who keep the crew together and sane as Earth becomes an ever more distant memory. They are mostly people dealing with problems of the crew’s morale and organizing efforts to solve their technical problems. Although towards the end of the book things get a bit more philosophical (the death and rebirth theme does have an effect on them), there is very little in the way of development in their characters.

Most of the novel is set in space so the future history of Earth is not all that important. We do get a glimpse of a society where Sweden has become the centre of power in the world after a nuclear war that almost doomed the planet. IKEA everywhere, surely this must count as a dystopia. Anderson, American of Danish descent, also weaves in some reverences to Scandinavian mythology, something that returns in many of his novel. It’s a bit of an odd contrast really, the cyclic nature of the universe as described in this novel, reminded me more of Hindu mythology.

According to the blurb on the cover, James Blish considers this book the ultimate hard science fiction novel. There is something to be said for that. I have rarely read a novel with such rigorous scientific underpinnings. Anderson had a degree in physics and in other novels it is quite clear that he thought about the properties of fictional planets he created. In Tau Zero he takes it way beyond that and makes physics the main character. The scope of the novel, in time and space is almost beyond comprehension (something the author points out several times in the text). Anderson takes hard science fiction as far as it will go; in that sense it is the ultimate novel in this particular sub-genre. That being said, it does not escape the shortcomings generally associated with the sub-genre. I’d say it is a must read for fans of hard science fiction only.

Full Details

Full Details