Automata 101: The Artist as Golem Maker – Part Two

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. This blog will outline her experiences teaching an Honors English Composition course about created entities, beginning with the golem of Jewish legend and continuing through cyborgs, robots, androids, and artificial intelligence.

“They’re all Jewish, superheroes. Superman, you don’t think he’s Jewish? Coming over from the old country, changing his name like that. Clark Kent, only a Jew would pick a name like that for himself.” (The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, 585).

“They’re all Jewish, superheroes. Superman, you don’t think he’s Jewish? Coming over from the old country, changing his name like that. Clark Kent, only a Jew would pick a name like that for himself.” (The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, 585).

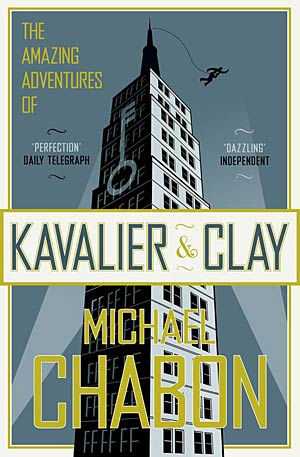

The students and I concluded our examination of Kavalier and Clay by looking at the role of comics in the book and how they connect to the protagonists and the figure of the golem. One thing that I like about Michael Chabon is his symbolism is often obvious, but it is executed so beautifully that unwrapping it is a joy. The students, of course, missed much of the obvious, so it was fun watching them see the symbolism unfold. For example, the first viable superhero whom Sammy and Joe create is the Escapist, whose alter ego is Tom Mayflower. It was easy for them to see how Joe–who trained in Prague as an escape artist and a magician and who had to escape Czechoslovakia stuffed in a coffin with the Golem of Prague–is a model for the Escapist. However, the fact that Tom Mayflower represents Sammy was a bit harder for them to see. Tom is crippled just as Sammy is. Tom is an orphan, and Sammy had an absent father, a circus strong man. A similar strong man figure, Big Al, serves as Tom’s surrogate father in the comic. Through Tom and the Escapist, Sammy and Joe are able to fight their personal demons (and Hitler) in the pages of the monthly magazines they create. However, Chabon does not want us to forget that their actions create a golem not just a superhero. He ends the chapter of the Tom Mayflower back-story by connecting Tom and his compatriots in their theater lair with their youthful creators, Kavalier and Clay:

The sound of their raised voices carries up through the complicated antique ductwork of the grand old theater, rising up and echoing through the pipes until it emerges through a grate in the sidewalk, where it can be heard clearly by a couple of young men who are walking past, their collars raised against the cold October night, dreaming their elaborate dream, wishing their wish and teasing their golem into life. (134)

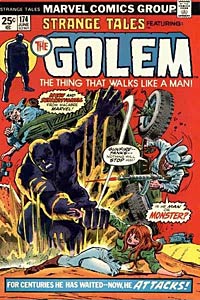

From Joe Kavalier’s first attempt at drawing a golem superhero on his first morning in New York to his magnum opus, a 2,256-page, wordless script called The Golem!, Chabon never lets us forget about the connection between the superhuman golem and America’s comic superheroes. The class and I looked back to Piercy again and again to examine Joseph the golem’s role as a superhero protecting the ghetto. We talked about his size, strength, and ability to heal rapidly. Also he was a more strategic thinker than the humans. He could only die through kabalistic magic. This constant comparison back to Joseph helped the students see what Chabon was attempting in his comparison.

However, through all of this, Chabon wants us to see that we can’t rely on golems any more than we can rely on superheroes. After all, the Jews of Prague don’t activate their golem to fight Hitler. Instead, they send it away in order to protect it. When the box with that same golem mysteriously arrives at Sammy’s home many years after the war, it is nothing but a box of dirt. According to Jewish legend, when it left its homeland, it disintegrated and lost its potency.

However, through all of this, Chabon wants us to see that we can’t rely on golems any more than we can rely on superheroes. After all, the Jews of Prague don’t activate their golem to fight Hitler. Instead, they send it away in order to protect it. When the box with that same golem mysteriously arrives at Sammy’s home many years after the war, it is nothing but a box of dirt. According to Jewish legend, when it left its homeland, it disintegrated and lost its potency.

Chabon’s message is that the modern golem is found in the creation of art. His own piece about golems and novel writing shows this. I ended the class by reading an engaging passage from the book, and I will end this blog in the same way. Here, Joe is thinking about all of the detritus of his life as a comic book artist:

In literature and folklore, the significance and the fascination of golems—from Rabbi Loew’s to Victor von Frankenstein’s—lay in their soullessness, in their tireless inhuman strength, in their metaphorical association with overweening human ambition, and in the frightening ease with which they passed beyond the control of their horrified and admiring creators. But it seemed to Joe that none of these—Faustian hubris, least of all—were among the true reasons that impelled men, time after time, to hazard the making of golems. The shaping of a golem, to him, was a gesture of hope, offered against hope, in a time of desperation. It was the expression of a yearning that a few magic words and an artful hand might produce something—one poor, dumb, powerful thing—exempt from the crushing strictures, from the ills, cruelties, and inevitable failures of the greater Creations. It was the voicing of a vain wish, when you got down to it, to escape. (582).

Full Details

Full Details

5 Comments

These Automatia posts are consistently engaging and fresh.

So far, a favourite blog series! I relate well to the erudite content, albeit that my contributions are limited. One thing this post has brought under my attention, is one more book of Chabon I need to read. Admittedly, "The Yiddish Policemen’s Union" did not appeal to me much, although I can still recognise it as very good book (deserves a second reading sometime in the future).

Thanks, Emil and Rico. I’ve really enjoyed writing them. @Emil, I did not think "The Yiddish Policeman’s Union" was all that great either. The cover of "Kavalier and Clay" drew me in long before I bought the book, then my research into "golem novels" gave me a reason to buy the book. Now I want to read more Chabon. "Summerland," "The Final Solution" and "Gentlemen of the Road" are on my list.

Great post. It makes me realize just how layered and nuanced Kavalier and Clays is. I approached it from a comic-book reader’s perspective, and having done research and writing on comic books before I thought it was a wonderful encapsulation of the early comic book culture: young men restless for their big chance and for escapism, the dreams of young Jewish men in America, the plight and perils of navigating copyright with trademark characters (Superman’s creators didn’t hold onto the right but Bob Kane, creator of Batman, wisely held on to it), the influence of WWII, the senate hearings and the concern over the influence of comic books on kids in the 1950’s, etc. The golem thing left me puzzled, but the link between the golem as a Jewish superhero and the superheroes created by people like Kavalier and Clay illuminates that aspect of the book for me. I’d add to Chabon’s excerpt on the Golem shown above, that it’s not just about ambition gone too far but it’s also, a la Peter Parker, about the responsibility that goes with great power. If you have a creation, you have a responsibility to it. Dr. Frankenstein shunned his beast and it went wild. Great post Rhonda.

@Mattastrophic, I agree with what you say about Chabon and his ideas about creation. I think he stresses that creators must be anti-Frankensteins in the way they handle what they create. I think that Sammy and Josef are sad that the Escapist is sold off and ended at the end of the book. However, we, the readers, are smart enough to see that the Escapist had become a bit of a Frankenstein without their stewardship. So many people had altered the Escapist in their absence that the comic had gone a bit wild and they could not bring it back.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.