Forays into Fantasy: Robert E. Howard’s Conan

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Honestly, I didn’t think Robert E. Howard’s series of Conan stories, written and mostly published during the first half of the 1930s, would be of much interest to me. But given their importance as the tales that mark the beginning of a major subgenre that is still going strong today—what would come to be known as sword and sorcery—I thought my fantasy history tour would be incomplete without at least giving them a look. Given the continued popularity and influence of these stories, I should have known that there would be more to them than my preconceptions of a giant barbarian warrior with an equally giant sword hacking his way from one adventure to the next (not that there isn’t some truth to that description), and it turns out there are good reasons that Howard’s stories are considered central to the development of fantasy, and that the best of them are still interesting and enjoyable today.

Honestly, I didn’t think Robert E. Howard’s series of Conan stories, written and mostly published during the first half of the 1930s, would be of much interest to me. But given their importance as the tales that mark the beginning of a major subgenre that is still going strong today—what would come to be known as sword and sorcery—I thought my fantasy history tour would be incomplete without at least giving them a look. Given the continued popularity and influence of these stories, I should have known that there would be more to them than my preconceptions of a giant barbarian warrior with an equally giant sword hacking his way from one adventure to the next (not that there isn’t some truth to that description), and it turns out there are good reasons that Howard’s stories are considered central to the development of fantasy, and that the best of them are still interesting and enjoyable today.

One reason I hadn’t approached them before was my memory of the endless rows of Conan paperbacks on bookstore shelves while haunting the science fiction and fantasy sections during the 1970s, along with the multiple similar series, spinoffs, and even parodies. By that time, sword and sorcery had been stereotyped as the realm of muscular barbarians, scantily-clad damsels in distress, and escapist adventure, and the sheer repetitiveness of the cover images seemed to verify it. As it turns out, this reaction was unfair to Howard’s creation, which went through a long and confusing publishing history that in some ways took the character further and further from its origin in Howard’s stories.

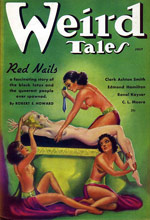

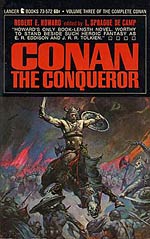

Though written while in his late twenties, Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories, published in Weird Tales between 1932 and 1936, are the culmination of his pulp fantasy writing, and are his most popular works. He completed twenty-one Conan stories prior to his death in 1936, including the only novel, Hour of the Dragon (later retitled Conan the Conqueror for book publication). The stories arose from Howard’s interest in the historical interplay between barbarian cultures and civilization, which he saw as a cycle of rise and fall. Every civilization eventually becomes decadent and weak, and is overcome by a stronger barbarian culture, which upon victory develops its own civilization, and the cycle continues. He had utilized some of the same themes in his westerns and historical tales (Howard was an amazingly prolific pulp writer, publishing fiction in many genres), and the endurance of his work on Conan is in part the result of its crystallizing this theme, which gives these stories—especially the later ones like “Beyond the Black River” and “Red Nails”, thematic interest beyond their accomplishment as top-notch pulp adventure tales.

Despite their popularity among Weird Tales readers in the thirties, the stories were unavailable for the next fifteen years, until resurfacing in 1950, when Gnome Press published Hour of the Dragon in hardcover, followed by a series of six more books during the fifties. While getting all of the available Conan stories back into print and restoring their popularity, the Gnome Press series also began the dubious practice, to be expanded on by subsequent publishers, of tampering with Howard’s texts, changing titles, and attempting to establish a chronological ordering that Howard had not intended.

Despite their popularity among Weird Tales readers in the thirties, the stories were unavailable for the next fifteen years, until resurfacing in 1950, when Gnome Press published Hour of the Dragon in hardcover, followed by a series of six more books during the fifties. While getting all of the available Conan stories back into print and restoring their popularity, the Gnome Press series also began the dubious practice, to be expanded on by subsequent publishers, of tampering with Howard’s texts, changing titles, and attempting to establish a chronological ordering that Howard had not intended.

The paperback series I remember seeing in stores was the one begun in 1968 and continued through 1977, under the guidance of L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter, and with memorable covers by Frank Frazetta, which was originally published by Lancer before being taken over by Ace. This series of twelve books attempted to establish a chronology for Conan’s history, reordering and even rewriting parts of Howard’s original stories, while supplementing them with completions of Howard’s fragments and plot outlines left unfinished at his death, and adding several completely new stories, written by de Camp and Carter. Another seven books by de Camp and Carter, along with contributions from Poul Anderson and others, continued into the early eighties, at which time the rights to publish Conan material shifted to Tor Books. As Conan’s popularity grew in response to the two films starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Tor proceeded to publish an additional forty-two Conan books by various authors, continuing the series through 1997. The first seven were authored by a pre-Wheel of Time Robert Jordan. During most of these years, the stories in their original versions had been out of print.

Reading the original unaltered Howard stories, then, was not an easy task prior to 2000, when a two-volume collection was issued as part of the Fantasy Masterworks series, with the definitive Wandering Star editions (now published in three volumes by del Rey) following in 2003-05. Looking into the question of which of these stories are considered the most important or essential by critics and fans, I came up with the eight discussed here. The settings and plots described are indicative of the surprising variety found throughout the series, as we see Conan in numerous career phases, landscapes, and circumstances. Click on the story titles for links to online public domain texts.

“The Frost Giant’s Daughter”: A young Conan pursues a supernatural siren across a frozen landscape after a battle, in a story inspired by Greek mythology. The result is a moody and mysterious piece, and a short glimpse into Conan’s origins in the frozen northern reaches of Hyboria, the setting Howard would continue to explore throughout the series.

“The Frost Giant’s Daughter”: A young Conan pursues a supernatural siren across a frozen landscape after a battle, in a story inspired by Greek mythology. The result is a moody and mysterious piece, and a short glimpse into Conan’s origins in the frozen northern reaches of Hyboria, the setting Howard would continue to explore throughout the series.

“The Tower of the Elephant”: During his time as a wandering thief, Conan takes on the challenge of stealing a priceless magical gem from a sorcerer’s tower, where he finds the source of the magician’s power—a tragic Lovecraftian alien with the head of an elephant—being held captive. Definitely one of the most memorable Conan stories, it contains some of the most brilliant images of the series, and may be the closest to what readers would expect to find in Weird Tales.

“Queen of the Black Coast”: Conan joins a crew of pirates, plundering ships along the coastline with Bêlit, the pirates’ beautiful queen, who becomes his lover, before the crew is lured into a Heart of Darkness-like trip down a haunted river to its magical source, with tragic consequences. This story sees Conan at his most despairing, and closest to death, while also portraying his greatest romance, resulting in a story of emotional extremes.

“The People of the Black Circle”: Conan, now a tribal chieftain in a mountainous land reminiscent of ancient India and Afghanistan, kidnaps a Vendyhan princess in order to ransom a group of his captured men. He ends up deciding to help her get revenge for her brother’s death against a magical cult of Seers who are attempting to manipulate the politics of the region for reasons of their own, in a story that delves most deeply into the magical aspects of Conan’s world.

The Hour of the Dragon: The only Conan novel, and one of just two novels Howard wrote, The Hour of the Dragon is set later in Conan’s life, when he has achieved the kingship of Aquilonia. Deposed by conspirators who have magically revived the mummified remains of the ancient sorcerer Xaltotun, the novel tells of Conan’s quest to regain his throne and thwart Xaltotun, who has ambitions well beyond those of his co-conspirators. Listed as one of the top 100 fantasy novels by both Pringle and Cawthorn/Moorcock, I found the novel to be entertaining but ultimately exhausting reading, with Conan progressing from one perilous adventur after another as he moves closer to his goal. (Readers of Edgar Rice Burroughs will be familiar with the plot pattern.) Pulp adventure is easier to digest in smaller doses, and the novel was written with serialization in mind, appearing as it did in five consecutive issues of Weird Tales, each with its own cliffhanger ending. Despite the acclaim, I would suggest that readers new to Conan, as I was, begin with the shorter tales, especially the next two on my list.

The Hour of the Dragon: The only Conan novel, and one of just two novels Howard wrote, The Hour of the Dragon is set later in Conan’s life, when he has achieved the kingship of Aquilonia. Deposed by conspirators who have magically revived the mummified remains of the ancient sorcerer Xaltotun, the novel tells of Conan’s quest to regain his throne and thwart Xaltotun, who has ambitions well beyond those of his co-conspirators. Listed as one of the top 100 fantasy novels by both Pringle and Cawthorn/Moorcock, I found the novel to be entertaining but ultimately exhausting reading, with Conan progressing from one perilous adventur after another as he moves closer to his goal. (Readers of Edgar Rice Burroughs will be familiar with the plot pattern.) Pulp adventure is easier to digest in smaller doses, and the novel was written with serialization in mind, appearing as it did in five consecutive issues of Weird Tales, each with its own cliffhanger ending. Despite the acclaim, I would suggest that readers new to Conan, as I was, begin with the shorter tales, especially the next two on my list.

“Beyond the Black River”: Conan, now a mercenary and scout at Fort Tuscelan, on the frontier of Aquilonia, tries to help repel an invasion by the Pictish barbarians and their sorcerous leader. He manages to help save the settlers, but the fort is destroyed in this fantasy version of a Western, with Conan cast as the hero who is allied with civilization, but who really has more in common with the primitive life that an encroaching civilization replaces. In Westerns, the stories end with civilization triumphant, even though the hero may not have a place in it. Howard turns this idea on its head in “Beyond the Black River,” as there is a realization that the barbarians have only temporarily been slowed in their inevitable triumph over the civilized land. As one of the few survivors of the battle puts it, in one of Howard’s best-known quotations: “‘Barbarism is the natural state of mankind … Civilization is unnatural. It is a whim of circumstance. And barbarism must always ultimately triumph.’”

“Red Nails”: If “Beyond the Black River” is Howard’s reversal of the American frontier mythology, “Red Nails” is his attempt to elaborate on why civilizations ultimately fall. Conan and Valeria—a female warrior he is in pursuit of—stumble into the weird ancient city of Xuchotl, where they become involved in a feud between two factions, who have been slowly killing each other off within this enclosed city, completely cut off from nature and the outside world. Agreeing to help one of the factions, Conan and Valeria are ultimately betrayed and can only escape as both tribes, who can conceive of no other purpose than to destroy each other, continue toward their doom. Howard had indicated that this allegory of a degenerate civilization was to be his final fantasy tale, as he hoped to find a way to continue his writing career outside the pulp ghetto, concentrating on Westerns during the last few months of his career. Whether he would have returned to Conan at some point will never be known, since Howard, distraught at his mother’s impending death, shot himself less than a year after “Black Nails” was written.

“Red Nails”: If “Beyond the Black River” is Howard’s reversal of the American frontier mythology, “Red Nails” is his attempt to elaborate on why civilizations ultimately fall. Conan and Valeria—a female warrior he is in pursuit of—stumble into the weird ancient city of Xuchotl, where they become involved in a feud between two factions, who have been slowly killing each other off within this enclosed city, completely cut off from nature and the outside world. Agreeing to help one of the factions, Conan and Valeria are ultimately betrayed and can only escape as both tribes, who can conceive of no other purpose than to destroy each other, continue toward their doom. Howard had indicated that this allegory of a degenerate civilization was to be his final fantasy tale, as he hoped to find a way to continue his writing career outside the pulp ghetto, concentrating on Westerns during the last few months of his career. Whether he would have returned to Conan at some point will never be known, since Howard, distraught at his mother’s impending death, shot himself less than a year after “Black Nails” was written.

The roles Conan took on throughout his life, and the range of settings encountered throughout his wandering career, as described in the subset of stories discussed above, gives some indication of why Howard’s tales maintain an interest beyond the pulp adventure aspects. The stories are set in the land of Hyboria, made up of multiple kingdoms and city-states, in a time period described as being after the fall of Atlantis and prior to the rise of the civilizations we know from history. This creation of a Hyborian Age allowed Howard to develop several interesting ideas and story strategies within the series. First, he was able to indulge his interest in historical fiction, without having to be overly concerned with historical detail, yet still making use of various historical settings. Scandinavian winter, the Barbary Coast, ancient India, a lost Aztec city, the American West—these and other settings, thinly disguised, all coexist within the confines of Hyboria and its environs. Some have criticized Howard for his use of actual place names and the mishmash of settings in his Hyborian stories, implying a laziness in his world-building, but my impression is that these effects were intentional, and can be seen as a legitimate use of fantasy to pursue the themes and story varieties he was interested in. (It also provided fertile ground for the never-ending continuation of Conan’s adventures in novels and comics since the 1970s.)

The idea of the Hyborian Age also emphasizes Howard’s theme of the rise and fall of civilizations. By positing an early Atlantean civilization, followed by a Hyborian Age (whose own fall is foreshadowed in “Beyond the Black River”), he keeps this theme always in the background of the stories. There is a sense throughout that all the great efforts of humanity to hold back the tide of barbarism are ultimately doomed, and possibly misguided, creating a sense of foreboding and futility in these stories that I would not have expected in pulp fantasy. This is an outgrowth of Howard’s reading of history, but it may also have been affected by the fact that these stories were composed during the depths of the Great Depression, and in the midst of trying to deal with whatever personal demons would ultimately lead to Howard’s suicide.

The idea of the Hyborian Age also emphasizes Howard’s theme of the rise and fall of civilizations. By positing an early Atlantean civilization, followed by a Hyborian Age (whose own fall is foreshadowed in “Beyond the Black River”), he keeps this theme always in the background of the stories. There is a sense throughout that all the great efforts of humanity to hold back the tide of barbarism are ultimately doomed, and possibly misguided, creating a sense of foreboding and futility in these stories that I would not have expected in pulp fantasy. This is an outgrowth of Howard’s reading of history, but it may also have been affected by the fact that these stories were composed during the depths of the Great Depression, and in the midst of trying to deal with whatever personal demons would ultimately lead to Howard’s suicide.

This dark mood also makes its way into Conan’s character which, along with the Hyborian setting, is of course the other unifying aspect of these stories. Conan seems to understand the futility of humanity’s civilizing impulse, seeing it from the perspective of a barbarian outsider who is intelligent, accomplished, and ambitious enough to adapt to whatever setting he finds himself in, preying off civilization, offering his services to it, or ruling it, as he makes his way through his life. As he puts it in “Beyond the Black River”:

“I’ve roamed far; farther than any other man of my race ever wandered. I’ve seen all the great cities of the Hyborians, the Shemites, the Stygians and the Hyrkanians. I’ve roamed in the unknown countries south of the black kingdoms of Kush, and east of the Sea of Vilayet. I’ve been mercenary captain, a corsair, a kozak, a penniless vagabond, a general – hell, I’ve been everything except a king, and I may be that, before I die.” The fancy pleased him, and he grinned hardly. Then he shrugged his shoulders and stretched his mighty figure on the rocks.

Conan is a pulp existentialist. He has no need for any culture, creed, or ideology, and is suspicious of them all. None of these things amount to anything in the long run, civilizations will fall, so Conan will enjoy life while he can, indulge his impulses, while answering only to his own internal moral code.

I seek not beyond death. It may be the blackness averred by the Nemedian skeptics, or Crom’s realm of ice and cloud, or the snowy plains and vaulted halls of the Nordheimer’s Valhalla. I know not, nor do I care. Let me live deep while I live; let me know the rich juices of red meat and stinging wine on my palate, the hot embrace of white arms, the mad exultation of battle when the blue blades flame and crimson, and I am content. Let teachers and priests and philosophers brood over questions of reality and illusion. I know this: if life is illusion, then I am no less an illusion, and being thus, the illusion is real to me. I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content.

I’d been prepared to dismiss the Conan stories as a series of violent male adolescent wish fulfillment fantasies. And to some degree they are, especially some of the lesser stories not discussed here, but there is more to them, and I would recommend fantasy fans at least sample a few of the better ones. The stories have an inherent interest for the reasons I’ve described, and they have been extremely influential as the fountainhead of the sword and sorcery subgenre. The term was coined by Fritz Leiber in 1961, to describe the sort of magical, historical, swashbuckling stories written by Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, C. L. Moore, and Leiber himself, among others. With his Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser tales, Leiber had brough humor to sword and sorcery, and Michael Moorcock would use the genre to question its own heroic underpinnings, creating his Elric stories in part in order to examine the stereotypes of the genre that had initially put me off exploring it. Current practitioners of sophisticated “new sword and sorcery”, many of which are featured in the recent anthology Swords and Dark Magic, include Steven Erikson and Joe Abercrombie. Fans of these authors will enjoy taking a look at their original inspiration in the stories of Robert E. Howard.

I’d been prepared to dismiss the Conan stories as a series of violent male adolescent wish fulfillment fantasies. And to some degree they are, especially some of the lesser stories not discussed here, but there is more to them, and I would recommend fantasy fans at least sample a few of the better ones. The stories have an inherent interest for the reasons I’ve described, and they have been extremely influential as the fountainhead of the sword and sorcery subgenre. The term was coined by Fritz Leiber in 1961, to describe the sort of magical, historical, swashbuckling stories written by Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, C. L. Moore, and Leiber himself, among others. With his Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser tales, Leiber had brough humor to sword and sorcery, and Michael Moorcock would use the genre to question its own heroic underpinnings, creating his Elric stories in part in order to examine the stereotypes of the genre that had initially put me off exploring it. Current practitioners of sophisticated “new sword and sorcery”, many of which are featured in the recent anthology Swords and Dark Magic, include Steven Erikson and Joe Abercrombie. Fans of these authors will enjoy taking a look at their original inspiration in the stories of Robert E. Howard.

Full Details

Full Details

2 Comments

Thank you for the nice article about the Conan stories. I enjoyed them as an older teen and into my early 20s. I didn’t make much distinction between the stories written by Howard and those of Carter and de Camp. I would also recommend to anyone interested in the genre that they find copies of Karl Edward Wagner’s novels and stories of the immortal warrior Kane. These are pretty well-written and very dark, but entertaining.

I didn’t mention it in the post, but I’d noticed that Karl Wagner edited a three-volume Conan collection in 1977, that was the first to restore Howard’s original texts, but I don’t think it was in print long. I think he also wrote some Conan stories himself, and was instrumental in keeping the sword and sorcery tradition going.

I don’t have any examples of the books on hand, but the covers of those Lancer/Ace paperbacks usually list Howard, de Camp and Carter as co-writers. It’s not clear that readers of them would have known which pieces were more or less by Howard, and which were by de Camp and/or Carter…

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.