Frankenstein’s Forefathers

We all know that Frankenstein’s monster was brought to life by powerful bolt of lightening. The image of him strapped to his iron bed as electricity courses through his body is an iconic Hollywood image. Never mind that such never transpired in Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel. For many of us, that is how he was born, whatever the book says. If, however, you were dismayed at the absence of such an origin the original Frankenstein, don’t be. The Creature may very well have been born from a thunderclap.

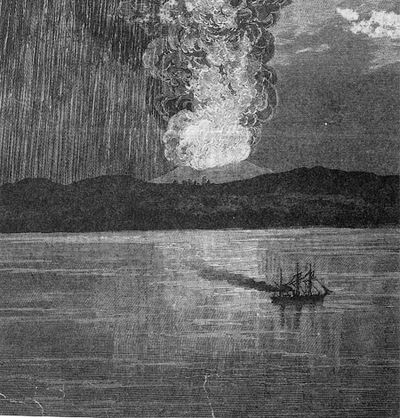

It was the summer of 1816 when an eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley traveled with her husband, the incomparable Percy Blysshe Shelley, to Lake Geneva, where they rented a house adjacent to their friend, Lord Byron. The three of them were joined by Byron’s personal nurse (and likely lover), John Polidori. This was the Year of No Summer, when the Mt. Tambora eruption (the most powerful in recorded history) released so much ash into the atmosphere that temperatures plummeted in many areas of the world. One of the hardest hit areas was Lake Geneva, where it “proved a wet, ungenial summer”, according to Mrs. Shelley, “and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house.” So, instead of spending their “pleasant hours on the lake, or wandering on its shores,” as they had done before Tambora’s ash blotted out the sun, they plunged themselves into (what else?) books:

It was the summer of 1816 when an eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley traveled with her husband, the incomparable Percy Blysshe Shelley, to Lake Geneva, where they rented a house adjacent to their friend, Lord Byron. The three of them were joined by Byron’s personal nurse (and likely lover), John Polidori. This was the Year of No Summer, when the Mt. Tambora eruption (the most powerful in recorded history) released so much ash into the atmosphere that temperatures plummeted in many areas of the world. One of the hardest hit areas was Lake Geneva, where it “proved a wet, ungenial summer”, according to Mrs. Shelley, “and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house.” So, instead of spending their “pleasant hours on the lake, or wandering on its shores,” as they had done before Tambora’s ash blotted out the sun, they plunged themselves into (what else?) books:

Some volumes of ghost stories, translated from the German into French, fell into our hands. There was the History of the Inconstant Lover, who, when he thought to clasp the bride to whom he had pledged his vows, found himself in the arms of the pale ghost of her whom he had deserted. There was the tale of the sinful founder of his race, whose miserable doom it was to bestow the kiss of death on all the younger sons of his fated house, just when they reached the age of promise. His gigantic, shadowy form, clothed like the ghost in Hamlet, in complete armour, but with the beaver up, was seen at midnight, by the moon’s fitful beams, to advance slowly along the gloomy avenue. The shape was lost beneath the shadow of the castle walls; but soon a gate swung back, a step was heard, the door of the chamber opened, and he advanced to the couch of the blooming youths, cradled in healthy sleep. Eternal sorrow sat upon his face as he bent down and kissed the forehead of the boys, who from that hour withered like flowers snapt upon the stalk. I have not seen these stories since then; but their incidents are as fresh in my mind as if I had read them yesterday.

These stories famously inspired the Geneva circle (Lord Byron, Polidori, and Percy and Mary Shelley) to write their own tales of woe. It was Byron’s idea. “We shall each write a ghost story,” he proclaimed. The game was afoot. It was due to that challenge that Lord Byron wrote a fragment of a story that started the vampire trope in Western literature. Polidori, according to Shelley, penned a god-awful story “about a skull-headed lady, who was so punished for peeping through a key-hole—what to see I forget—something very shocking and wrong.” Eventually, Polidori ditched this story in favor of Byron’s, writing his own novel, The Vampyre, based on Byron’s fragment. The great Percy Shelley also began a story (based on his own childhood), but, as with the other two, he quickly gave up. As Mary put it, “The illustrious poets also, annoyed by the platitude of prose, speedily relinquished the uncongenial task.”

We all know who must have won Byron’s challenge. Mary Shelley was the only one to actually complete her “ghost story,” Frankenstein. It was unlike any ghost story ever written, however, because, instead of a bodiless soul, this “ghost,” was a reanimated body. Mrs. Shelley had turned the ghost story on its ear.

We all know who must have won Byron’s challenge. Mary Shelley was the only one to actually complete her “ghost story,” Frankenstein. It was unlike any ghost story ever written, however, because, instead of a bodiless soul, this “ghost,” was a reanimated body. Mrs. Shelley had turned the ghost story on its ear.

The Geneva Wager is a story you may have heard before. I remember hearing it when I first read Frankenstein as a teenager. It is, after all, where two monumental icons of 19th century horror originated. They are especially important icons for this time of year: Frankenstein’s monster and vampires are as essential to Hallowe’en as trick or treating. Yet one aspect of the story always eluded me: What were those stories that so captured the imagination of the Geneva circle that it would inspire monsters as enduring as the Creature and the Undead?

All I had to go on was Mary’s description, “Some volumes of ghost stories, translated from the German into French,” and a footnote describing the French title as Fantasmagoria. Even if I could find that tome, I don’t speak French! What is a linguistically impaired nerd to do? Eventually, of course, the Interwebs provided. It turns out Internet Archive (a rockin’ site that documents everything on the web and many things off it) has as a wonderful PDF scan of an 1813 edition, called Tales of the Dead. In it, you will find the two stories that Mary Shelley described. “The Death-Bride” (which she describes as “the History of the Inconstant Lover,” and “The Family Portraits,” (which she described in greatest detail) are particularly eerie tales that might keep you up at night, especially if you have a guilty conscience.

Full Details

Full Details

3 Comments

Very interesting. The story of this literary meeting in Geneva was also the subject of the film “Gothic,” a few decades back. Poetically speaking, Polidori and Byron just seem to have been along for the ride, and I expect they only half-cared about the spooky ghost stories. The incomparable Shelley, however, is described during the reading of one horrific poem: “suddenly shrieking and putting his hands to his head, [he] ran out of the room with a candle.” But even he did not write anything out of this wager, unless you count the editorial influence he had on “Frankenstein” itself.

Mary Godwin (not Mary Shelley yet, since at this time she was still Percy’s adulterous lover; the two would not legitimize their affair until a few short weeks after his wife’s suicide) is said to have modeled Victor Frankenstein’s philosophies on those of her lover’s and of his circle’s. Percy was notoriously obsessed with the symbolism of Prometheus as the great revolutionary myth, and Mary likewise called Victor the “Modern Prometheus.”

Looking forward to the next installment of this series!

I always love hearing this story and I am especially interested in the Archive. Thanks! What also gets me was Mary Shelley’s age. Wasn’t she something like 18 years old when she wrote it?!

Yay internet archive! At the beginning of your last paragraph I was going to tell you to call a librarian — this is the kind of research puzzle that reference librarians like myself love! But since the IA is run by archivists and librarians you kind of did so, anyway. It’s well worth exploring the site. The Wayback Machine is probably their most well-known project, but the open source catalog Open Library where you found this book is an equally interesting and ambitious project.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.