Literary Recognition for Science Fiction

Over the decades science fiction books have received little respect from the literary establishment. Most science fiction readers don’t give a damn either. Yet, in recent years I’m seeing signs of acceptance. I’m sure true fans of mimetic fiction still ignore our genre, but the larger society might be throwing us a few crumbs of admiration. Books that win the Pulitzer Prize tend to paint realistic portraits of complex characters. Science fiction has other goals, usually sculpting our hopes and fears about the future into an exciting story. That inherently makes science fiction a different art form compared to the literary novel. I wish the literati would recognize that the science fiction novel has its own aesthetics. But I also hope the average science fiction fan will understand what they are missing.

Over the decades science fiction books have received little respect from the literary establishment. Most science fiction readers don’t give a damn either. Yet, in recent years I’m seeing signs of acceptance. I’m sure true fans of mimetic fiction still ignore our genre, but the larger society might be throwing us a few crumbs of admiration. Books that win the Pulitzer Prize tend to paint realistic portraits of complex characters. Science fiction has other goals, usually sculpting our hopes and fears about the future into an exciting story. That inherently makes science fiction a different art form compared to the literary novel. I wish the literati would recognize that the science fiction novel has its own aesthetics. But I also hope the average science fiction fan will understand what they are missing.

Back in 2007, when Library of America published its first collection of Philip K. Dick novels, it felt like science fiction was finally getting a nod from the big boys. Library of America describes itself: “Founded in 1979, the nonprofit organization was created with a unique and unprecedented goal: to curate and publish authoritative new editions of America’s best writing, including acknowledged classics, neglected masterpieces, and historically significant documents and texts.” Publishing Philip K. Dick with Edith Wharton, Walt Whitman, James Baldwin, Louisa May Alcott, Mark Twain, Raymond Chandler, Kate Chopin, William Faulkner, Herman Melville, seems like a literary endorsement. I wish Phil had lived to see his books in LOA editions. And I wish his literary novels had LOA editions.

Library of America has since published Ursula K. Le Guin and Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and even Edgar Rice Burroughs, and H. P. Lovecraft. In 2012, LOA produced American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in a two-volume set. Collectively, those novels portray an alternate literary view of the 1950s. This week I wrote, “Who Still Reads 1950s Science Fiction?” and thought I’d get damn few readers. It’s gotten over 700 shares on Facebook, and 1,600 views. That’s far from what a news story about Pokémon would get, but a lot for my little blog. What surprised me, was how many younger readers loved 1950s books. Sometimes great literature is defined by great writing, other times, as books that last. A handful of science fiction novels are showing signs of lasting.

Library of America has since published Ursula K. Le Guin and Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and even Edgar Rice Burroughs, and H. P. Lovecraft. In 2012, LOA produced American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in a two-volume set. Collectively, those novels portray an alternate literary view of the 1950s. This week I wrote, “Who Still Reads 1950s Science Fiction?” and thought I’d get damn few readers. It’s gotten over 700 shares on Facebook, and 1,600 views. That’s far from what a news story about Pokémon would get, but a lot for my little blog. What surprised me, was how many younger readers loved 1950s books. Sometimes great literature is defined by great writing, other times, as books that last. A handful of science fiction novels are showing signs of lasting.

Recently I noticed that Everyman’s Library has an edition of The Foundation Trilogy by Isaac Asimov, listed in their catalog under Contemporary Classics, along with A. S. Byatt, Albert Camus, Raymond Chandler, D. H. Lawrence, Thomas Mann, and other powerful wordsmiths. Everyman’s Library’s other SF titles includes, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood and Stories of Ray Bradbury by Ray Bradbury. Asimov and Bradbury were added to their collection in 2010, after Library of America had come out with their Philip K. Dick volumes. I don’t know if that was keeping up with the Joneses, or if Everyman’s Library discovered The Foundation Trilogy is the most remembered science fiction story from the 1950s.

These publishers are famous for their uniform volumes that look classy. Everyman’s Library editions are elegant hardbacks, with thin white pages and an attached ribbon bookmark, which remind me of bibles.

These publishers are famous for their uniform volumes that look classy. Everyman’s Library editions are elegant hardbacks, with thin white pages and an attached ribbon bookmark, which remind me of bibles.

I poked around Modern Library, the grandfather of classic reprints in uniform editions, but didn’t spot any science fiction. However, their famous (infamous) list of 100 Best Novels does include Brave New World, 1984, Slaughterhouse-Five, and A Clockwork Orange. My recent post, “The Classics of Science Fiction in 12 Lists” mentions six other lists from sites identifying general classics that include some science fiction.

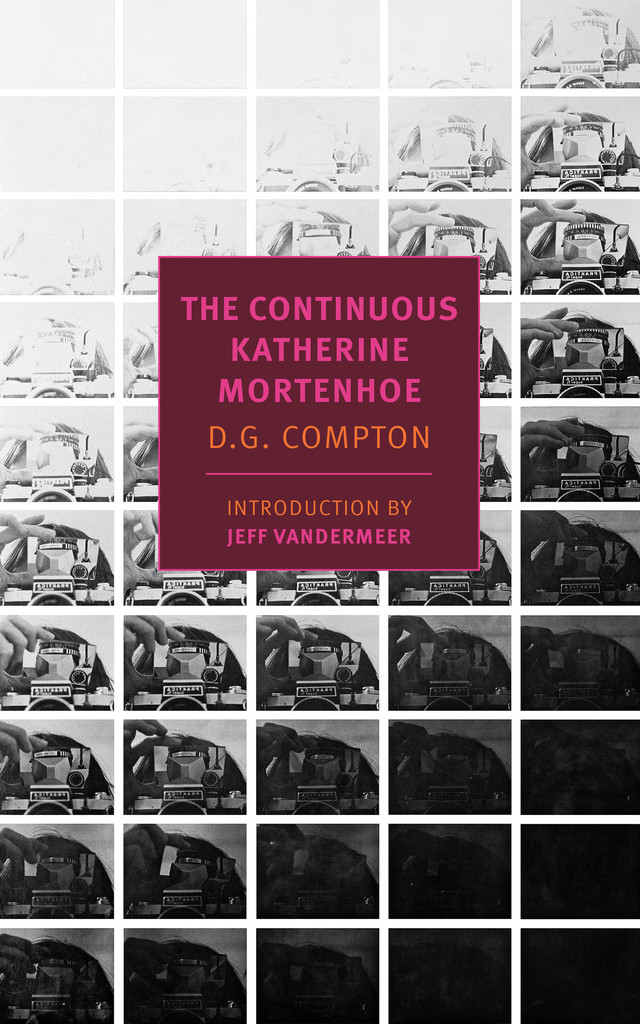

What got me started on this literary recognition scavenger hunt was noticing that the New York Review Books Classics, a prestigious publisher of quality paperbacks for literary elite readers, had two books by John Wyndham, The Chrysalids and Chocky. Wyndham, the author of The Day of the Triffids, has always garnered a bit more respect than the average science fiction writer. But NYRB Classics also publishes a collection of short stories by Robert Sheckley. That surprised me! And they reprinted The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe by D. G. Compton. I had first read Compton when he appeared back in the 1960s in the first series of Ace Science Fiction Specials. I’ve wondered what had happened to him. Compton had become a forgotten writer. What a way to be remembered.

Vintage Books, another quality trade publisher, has a nice uniform collection of books by Samuel R. Delany. Vintage had published a uniform collection of Philip K. Dick. Now Mariner Books publishes PKD, also with uniform covers, that makes the collection appear literary. While many older science fiction writers get reprinted only in eBook editions, PKD is in print in paper, eBook and audio, and for almost everything he wrote, including his crappiest novels, and his weirdly philosophical ramblings.

Most classic science fiction novels are available on Audible.com, as audio book editions, and that’s a kind of recognition too. Unfortunately, many of those same classics have no print edition, just eBook editions. Some of Robert A. Heinlein’s famous novels currently have no book you can hold edition.

On the other hand, many of the greatest science fiction books of all time are remembered in deluxe editions, some bound in expensive leather, from publishers like The Easton Press, Franklin Books, and The Folio Society. This doesn’t mean these books are literary masterpieces by academic standards, but they are books so well loved that people will spend $$$ for enduring, beautiful, timeless, bindings.

Science fiction has finally been accepted by the Best American series. The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy is appearing for the second time in 2016. The series editor is John Joseph Adams, and the guest editor is Karen Joy Fowler. It’s not that the genre was lacking in annual best-of-the-year anthologies, but this one will be seen with the other Best American series in bookstores, and that’s a kind of endorsement for the genre too.

Science fiction has finally been accepted by the Best American series. The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy is appearing for the second time in 2016. The series editor is John Joseph Adams, and the guest editor is Karen Joy Fowler. It’s not that the genre was lacking in annual best-of-the-year anthologies, but this one will be seen with the other Best American series in bookstores, and that’s a kind of endorsement for the genre too.

Newspapers like The New York Times and The Guardian, that once shunned the genre, are now spending more time reviewing science fiction books. This might be due to the expanded space provided by the web, or it might be due to science fiction being popular with people who use technology.

Since the 1970s, science fiction has often been taught in schools and colleges, but usually in special courses. I’m not sure anyone can get a degree in science fiction, just yet, but science fiction has a growing history, and an expansive body of work. This year, The Great Courses offered How Great Science Fiction Works. I listened to it on Audible, and I’m now watching it on The Great Courses Plus on my Roku. Dr. Gary K. Wolfe gives an excellent overview of the genre in 24 lessons. The major books he discusses can be found pictured at SF Signal. Wolfe ties them all together by theme, revealing the evolution of our genre.

Before the 1950s, science fiction as a genre, was known to few people. I’ve been trying to remember the first time a science fiction book came up in a popular movie. In 1985, with Back to the Future, Marty McFly’s father, George, was a science fiction writer. But he was the butt of jokes. There’s been science fiction movies almost as long as there has been movies. But can you remember the first time a character in a movie talked about reading a science fiction book? I can’t. There’s a kind of literary recognition when a title is mentioned inside a work of pop culture. Sometimes it’s obvious, like all the books slipped into Lost. Other times it might be a minor set piece. If you pay attention, science fiction books do get mentioned more often now. Anyone want to claim the first time?

All of the above aren’t real examples of literary recognition. There’s no official stamp of literary approval. There’s even a reactionary movement against the concept of “classic” books. Too many “great” books are by dead white guys, that many feel are no longer meaningful to our times. Today, there’s a growing demand for books that are recent, relevant, and representative. Literary quality or reputation no longer matter. By the standard of popularity, then science fiction is getting tremendous recognition, and it’s showing more diversity. Even mainstream literary writers dabble with science fictional story elements.

All of the above aren’t real examples of literary recognition. There’s no official stamp of literary approval. There’s even a reactionary movement against the concept of “classic” books. Too many “great” books are by dead white guys, that many feel are no longer meaningful to our times. Today, there’s a growing demand for books that are recent, relevant, and representative. Literary quality or reputation no longer matter. By the standard of popularity, then science fiction is getting tremendous recognition, and it’s showing more diversity. Even mainstream literary writers dabble with science fictional story elements.

However, has science fiction ever come close to The House of Mirth, Their Eyes Were Watching God, On the Road, To Kill a Mockingbird, Invisible Man, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Bell Jar, or A Signature of All Things? Those are just the literary novels that came to mind in five seconds. Like I said, the goals of science fiction are different. But what if science fiction included literary aspects too? So far, I’m still not hearing any claims that’s happening.

Full Details

Full Details

3 Comments

Interesting article again!

I’m not sure what you mean by the different goals of science fiction? I’m also not sure what you mean with the “literary aspects” of regular fiction, as if they differ from science fiction. The way I see it, the literary aspects of non-genre fiction aren’t different from those of speculative fiction.

The literary “value” of novels is determined by things like historical relevance, depth, complexity and originality. Just as there are tons of pulp speculative fiction novels, there are tons of pulp “mimetic” fiction books too.

As far as True Artistic Literature goes, the division is not between speculative fiction and mimetic fiction, but between quality and bad writing. Put a bit sharper, and more romantic, one of the dividing lines is the line between original artistic expression and commercial, generic product.

Maybe your love for 50s SF influences your viewpoint: obviously lots of those SF novels were pulp indeed. I don’t think there is generally less pulp in the speculative genre today, judging by all those generic covers the big publishers put out every month, I think speculative pulp has moved more towards fantasy. (But maybe that’s not really the full picture, as I don’t know anything about all that Star Wars fiction and other stuff derived from movies, games, etc., which seems pulpy & plentiful too.)

Quote: “But what if science fiction included literary aspects too? So far, I’m still not hearing any claims that’s happening.”

I disagree. Many books with genre plots and/or themes have been nominated for and/or won major literary prizes. And many of the mainstream/literary publishers (for example, Random House) publish books with genre plots and/or themes.

Bleebs, the difference between genre and literary to me, is literary fiction often feels autobiographical because they characters feel so real. Some literary fiction is thinly disguised reporting about real people and events. Since science fiction is more about ideas, and about the future, it’s very hard for it to be about real people, places and events.

Modern science fiction is far better written than older science fiction. Much of it has been influenced by literary fiction and MFA programs. But it seldom goes for that autobiographical quality I’m talking about.

Dalex, what books are you thinking about? One example you might be thinking about, is The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon. And it does have that autobiographical quality I’m talking about. However, it’s neither science fiction, or genre.

By the way, not all literary books are literary. Literary writers often incorporate genre techniques. You can feel that because the characters feel more like creations than being based on real people.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.