Reading the Pulps #4: “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” by David H. Keller, M.D.

Read it now: Amazing Stories February 1928 (from the Luminist League)

You might already own “The Revolt of the Pedestrian” in one of these anthologies:

- The Road to Science Fiction #2: From Wells to Heinlein edited by James Gunn

- Amazing Stories: 60 Years of the Best Science Fiction edited by Asimov/Greenberg

- The Twelfth Golden Age of Science Fiction Megapack (.99 cent ebook)

- The Best of Amazing Stories: The 1928 Anthology ($2.99 ebook)

Warning: This column contains spoilers.

If you only read science fiction for entertainment you could find “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” entertaining enough, especially if you get a hoot out of old-fashioned science fiction. A quick reading might suggest it’s a silly story, but I believe under the surface it has a number of nasty streaks. We generally think of science fiction as cheerleading for the final frontier. Reading “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” shows David H. Keller promoting something else.

My purpose in analyzing this tale is to show that science fiction wanted to be more than just entertainment. Science fiction can’t take itself too seriously because the genre is burdened by the prejudice that it’s not. However, some science fiction writers wanted to distinguish themselves by using science fiction to say something serious about society. The gold medal example of this is Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell. Keller wins no medal though.

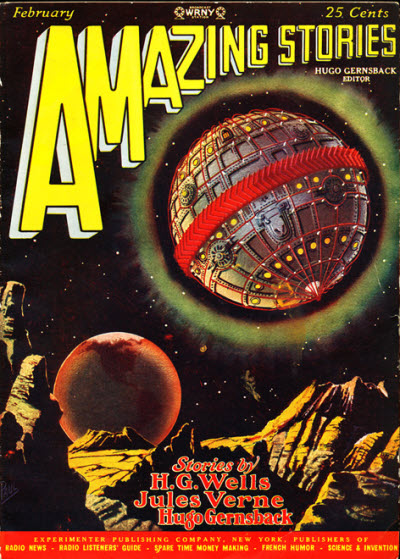

It is often assumed science fiction began genre in April of 1926 with the first issue of Amazing Stories edited by Hugo Gernsback. But that first issue was all reprints, with stories from 1845-1923, suggesting that science fiction had already been around at least 83 years. David H. Keller M.D. (1880-1966) was one of Gernsback early writers, and “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” was his first short story for Amazing. Few readers remember Keller or this story today

Hugo Gernsback took science fiction very seriously. “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” is an example of what Gernsback wanted: speculation, and extrapolation. Keller’s story isn’t much of a story as a polemic against mechanization if we are to assume Keller was serious. He could have gotten its idea on a whim, hoping to make a few bucks at a new magazine about the future. On the other hand, I think he was expressing his conservative views.

What I’d love to know is how Americans thought of science fiction in 1928. The term wasn’t in use yet, as Gernsback wanted to call his stories scientifiction – a tongue twister that would never be accepted. Stories involving travel to other planets had been around for a while, but only in journals and books that few people read.

On January 7, 1929, the Buck Rogers comic strip began running in newspapers. That comic strip was read by millions, and with the 1934 Flash Gordon strip, they probably spread science fictional ideas too far more Americans than Amazing Stories ever did. Buck Rogers originally appeared in Amazing Stories as a short story, but I’ve read so few stories from Gernsback Amazing to know if it was typical. Buck Rogers in the comic strip and serial was silly, even campy, which suggests it’s where the prejudice that science fiction wasn’t serious began. People used to call science fiction, “That crazy Buck Rogers stuff.”

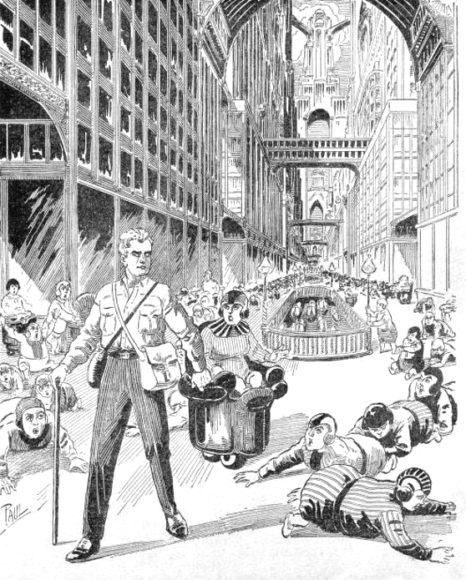

“The Revolt of the Pedestrians” is set many centuries in the future after humans divide into two species – the pedestrians and the automobilists. Automobilists have shrunken legs from always using automobiles or powered chairs called autocars. Eventually, the overwhelming majority of society become automobilists and decide pedestrians are anti-progress — a threat to society. They are outlawed, killed and assumed extinct.

Most of Keller’s story is narrative. There is very little drama or action. Keller may have gotten his central idea from The Time Machine by H. G. Wells, where humanity splits into two opposing species. I find it especially hard to believe that Keller thought automobiles were bad for humanity, or it would cause humans to devolve their legs. Logically, he should have known we spend far more time not using cars. Nor could a few centuries have caused the changes he suggests.

I believe Keller was writing about a divide in humanity in his own day, between conservatives and liberals. David H. Keller is now remembered as having been an extreme right-wing, anti-feminist, and racist. Cars and voting women were still new in 1928. Within the story, Keller also expresses pro-eugenic and pro-euthanasia ideas that were also common in the 1920s. The society of the automobilists is seen as socialist and scientific, whereas the rebelling pedestrians are advocates of back to nature and rugged individualists. Hating the automobilists they invent a kind of EMP device to switch-off technological society, thus killing billions of automobilists.

This isn’t escapist fun, but a vicious view. In a way, it prefigures Brave New World by Aldous Huxley that came out in 1932. “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” is an early dystopia. Why would Gernsback accept an anti-science, anti-technology story for Amazing Stories?

The story comes down to a battle between two families, and two men, the pedestrian Abraham Miller and the automobilist William Henry Heisler. They were even distant cousins, and an ancestor of Miller was killed by a distant ancestor of Heisler. The son of that slain victim works for generations to revenge the pedestrians.

For me, the story only had two engaging characters. Margaretta Heisler, child of the automobilist, is a biological throwback who has working legs. Because William Henry Heisler is rich he protects his daughter from being destroyed.

After that conversation, Heisler engaged the old man, whose sole duty was to investigate the subject of pedestrian children and find how they played and used their legs. Having investigated this, he was to instruct the little girl.

The entire matter of her exercise was left to him. Thus from that day on a curious spectator from an aeroplane might have seen an old man sitting on the lawn showing a golden-haired child pictures from very old books and talking together about the same pictures. Then the child would do things that no child had done for a hundred years—bounce a ball, skip rope, dance folk dances and jump over a bamboo stick supported by two upright bars. Long hours were spent in reading and always the old man would begin by saying:

“Now this is the way they used to do.”

Occasionally a party would be given for her and other little girls from the neighboring rich would come and spend the day. They were polite—so was Margaretta Heisler—but the parties were not a success. The company could not move except in their autocars, and they looked on their hostess with curiosity and scorn. They had nothing in common with the curious walking child, and these parties always left Margaretta in tears.

“Why can’t I be like other girls?” she demanded of her father. “Is it always going to be this way? Do you know that girls laugh at me because I walk?”

Heisler was a good father. He held to his vow to devote one hour a day to his daughter, and during that time gave of his intelligence as eagerly and earnestly as he did to his business in the other hours. Often he talked to Margaretta as though she were his equal, an adult with full mental development.

“You have your own personality,” he would say to her. “The mere fact that you are different from other people does not of necessity mean that they are right and you are wrong. Perhaps you are both right—at least you are both following out your natural proclivities. You are different in desires and physique from the rest of us, but perhaps you are more normal than we are. The professor shows us pictures of ancient peoples and they all had legs developed like yours. How can I tell whether man has degenerated or improved? At times when I see you run and jump, I envy you. I and all of us are tied down to earth—dependent on a machine for every part of our daily life. You can go where you please. You can do this and all you need is food and sleep. In some ways this is an advantage. On the other hand, the professor tells me that you can only go about four miles an hour while I can go over one hundred.”

“But why should I want to go so fast when I do not want to go anywhere?”

“That is just the astonishing thing. Why don’t you want to go? It seems that not only your body but also your mind, your personality, your desires are old-fashioned, hundreds of years old-fashioned. I try to be here in the house or garden every day—at least an hour—with you, but during the other hours I want to go. You do the strangest things. The professor tells me about it all. There is your bow and arrow, for instance. I bought you the finest firearms and you never use them, but you get a bow and arrow from some museum and finally succeed in killing a duck, and the professor said you built a fire out of wood and roasted it and ate it. You even made him eat some.”

“But it was good, father—much better than the synthetic food. Even the professor said the juice made him feel younger.”

Heisler laughed, “You are a savage—nothing more than a savage.”

“But I can read and write!”

“I admit that. Well, go ahead and enjoy yourself. I only wish I could find another savage for you to play with, but there are no more.”

“Are you sure?”

“As much so as I can be. In fact, for the last five years my agents have been scouring the civilized world for a pedestrian colony. There are a few in Siberia and the Tartar Plateau, but they are impossible. I would rather have you associate with apes.”

“I dream of one, father,” whispered the girl shyly. “He is a nice boy and he can do everything I can. Do dreams ever come true?”

Heisler smiled. “I trust this one will, and now I must hurry back to New York. Can I do anything for you?”

“Yes—find someone who can teach me how to make candles.”

“Candles? Why, what are they?”

She ran and brought an old book and read it to him. It was called, “The Gentle Pirate,” and the hero always read in bed by candle light. “I understand,” he finally said as he closed the book. “I remember now that I once read of their having something like that in the Catholic churches. So you want to make some? See the professor and order what you need. Hum—candles—why, they would be handy at night if the electricity failed, but then it never does.”

“But I don’t want electricity. I want candles and matches to light them with.”

“Matches?”

“Oh, father! In some ways you are ignorant. I know lots of words you don’t, even though you are so rich.”

“I admit it. I will admit anything and we will find how to make your candles. Shall I send you some ducks?”

“Oh, no. It is so much more fun to shoot them.”

“You are a real barbarian!”

“And you are a dear ignoramus.” So it came to pass that Margaretta Heisler reached her seventeenth birthday, tall, strong, agile, brown from constant exposure to wind and sun, able to run, jump, shoot accurately with bow and arrow, an eater of meat, a reader of books by candlelight, a weaver of carpets and a lover of nature. Her associates had been mainly elderly men: only occasionally would she see the ladies of the neighborhood. She tolerated the servants, the maids and housekeeper. The love she gave her father she also gave to the old professor, but he had taught her all she knew and the years had made him senile and sleepy.

The other character I cared for was a pedestrian man who dressed as a woman working as a stenographer so he could spy on automobilist Heisler. This is a short scene, and almost an aside to the main story, so I wondered why Keller included it. I’m sure Keller was expressing his own prejudices here, but what did Amazing Stories readers make of this scene?

But for the first time in his life, he was in a big city. The firm on the floor below employed a stenographer. She was a very efficient worker in more ways than one and there was that about the new stenographer that excited her interest. They met and arranged to meet again. They talked about love, the new love between women. The spy did not understand this, having never heard of such a passion, but he did understand eventually, the caresses and kisses. She proposed that they room together, but he naturally found objections. However, they had spent much of their spare time together. More than once the pedestrian had been on the point of confiding in her, not only the impending calamity, but also his real sex and his true love.

In such cases where a man falls in love with a woman the explanation is hard to find. It is always hard to find. Here there was something twisted, a pathological perversion. It was a monstrous thing that he should fall in love with a legless woman when he might by waiting, have married a woman with columns of ivory and knees of alabaster. Instead, he loved and desired a woman who lived in a machine. It was equally pathological that she should love a woman. Each was sick—soulsick, and each to continue the intimacy deceived the other. Now with the city dying beneath him, the stenographer felt a deep desire to save this legless woman. He felt that a way could be found, somehow, to persuade Abraham Miller to let him marry this stenographer—at least let him save her from the debacle.

So in soft shirt and knee trousers he cast a glance at Miller and Heisler engaged in earnest conversation and then tiptoed out the door and down the inclined plane to the floor below. Here all was confusion. Boldly striding into the room where the stenographer had her desk, he leaned over her and started to talk. He told her that he was a man, a pedestrian. Rapidly came the story of what it all meant, the cries from below, the motionless auto-cars, the useless elevators, the silent telephones. He told her that the world of automobilists would die because of this and that, but that she would live because of his love for her. All he asked was the legal right to care for her, to protect her. They would go somewhere and live, out in the country. He would roll her around the meadows. She could have geese, baby geese that would come to her chair when she cried, “Weete, weete.”

The legless woman listened. What pallor there might be in her cheeks was skillfully covered with rouge. She listened and looked at him, a man, a man with legs, walking. He said he loved her, but the person she had loved was a woman; a woman with dangling, shrunken, beautiful legs like her own, not muscular monstrosities.

She laughed hysterically, said she would marry him; go wherever he wanted her to go, and then she clasped him to her and kissed him full on the mouth, and then kissed his neck over the jugular veins, and he died, bleeding into her mouth, and the blood mingled with rouge made her face a vivid carmine. She died some days later from hunger.

When I first read this story back in the early 1970s it just seemed like a silly spoof on evolutionary possibilities. I didn’t contemplate how the central idea would have been stupid even back in 1928. I didn’t think about how it could be a political statement.

The apparent hero of this story, Abraham Miller, is a mass murderer, destroying a world-wide civilization of billions. As part the story we see a city of millions thrown into chaos as its inhabitants try to crawl out of the city. I wonder if Keller wanted us to associate the name Abraham with Lincoln, or the Abraham of the Bible. I associated Abraham Miller with Adolph Hitler.

“The Revolt of the Pedestrians” has not been reprinted often. Few stories from the early days of Amazing Stories have, but reading “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” make me want to read more of those old stories to see what else Gernsback was philosophically promoting. Maybe there are more reasons than financial why Gernsback lost his magazine.

We generally assume science fiction was propaganda for progress, but this story is really a revolt against modernity. I used to think it amusing back in the 1970s when I took courses in the Modern Novel we mostly read books from the 1920s. A tremendous amount of change happened in that decade, and I guess Keller wasn’t too thrilled with them. The 1920s was a huge era for the KKK, with many state governors belonging to that racist organization. And like I mentioned above, Keller promotes eugenics within the story, which had been adopted by some states at that time. I guess Amazing Stories readers just assumed Keller’s ideas were part of the status quo.

Contemporary conservatives often seem anti-science today. Maybe they see liberals as a divergent species. I wonder if we’re still in a civil war over modernity. For the most part, I believe science fiction has taken the side of the Enlightenment, but I need to pay more attention when I read these old science fiction stories for their political philosophy.

Science fiction is always about the times in which it was written. Growing up in the 1960s I assumed science fiction reflected my liberal beliefs for my future, but now that I’m rereading these old stories I realize I had ignored obvious conservative hopes for their future. Since we’re living in a Donald Trump timeline, I wonder if some science fiction helped create it.

JWH

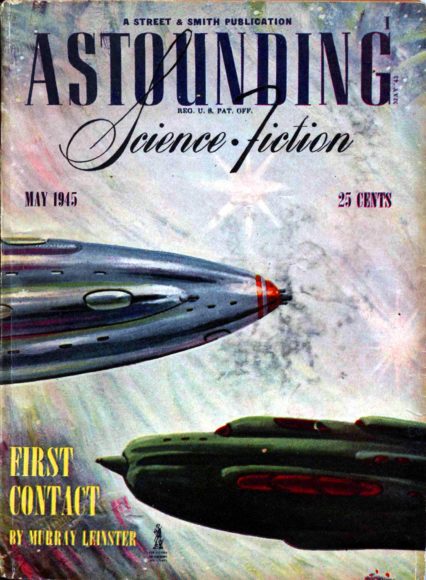

Reading the Pulps #3: Astounding Science Fiction

You can read digital scans of old issues of Astounding here:

- Project Gutenberg (quick HTML reading early issues)

- Pulp Magazine Archive (small selection with flipbook viewer)

- The Pulp Magazine Project (small selection in flipbook or pdf)

- Luminist League (large selection of cover images and pdf files)

“Be careful what you wish,” is a wise adage worth heeding. Back in 1971, when I discovered pulp magazines, I wished I owned a complete run of Astounding Science Fiction. I didn’t have the money or space, but for a few years, I bought a few hundred pulp and digest magazines from the 1920s-1960s. Even then they were dry crumbling old magazines that weren’t going to last much longer. I sold them when I needed money in 1975.

I didn’t know I needed to cancel that wish.

A few weeks ago, I began a new reading project. I decided to read my way through the 25 volumes of The Great SF Stories (1939-1963) edited by Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg. I even started a discussion group for several of us who want to read through v. 1-25 together.

Of course, many of those stories came from the classic pulp magazines Astounding Science Fiction and Amazing Stories, and I wanted to see what my favorite stories looked like with their original illustrations. I’m in a large group on Facebook called Space Opera Pulp where over eleven thousand members share pulp magazine art and illustrations. After posting one of the illustrations a member left a comment that he had bought the entire run of Astounding on discs from eBay.

To make a long story shorter, I ended up buying a 2-volume collection of the complete run of digital scans of Astounding Science Fiction (1930-1960). (Search eBay: “complete astounding science fiction DVD” – and be prepared to learn about CBR/CBZ readers if you buy the set.)

At first, I thought this might be a stupid impulse buy. There’s no way I’m going to read 359 issues of an old magazine. Besides, all those issues are free on the web if you know where to look. However, each issue runs 50-200 megabytes, with the complete set being 35.9 gigabytes. Buying them on discs saved me a lot of time.

I’ve used this archive every day since. Why I use it every day is the point of this essay. Why you’re reading this essay could be because you love science fiction from that era too.

I keep asking myself why am I so drawn to these old science fiction stories? Why mess with these old magazines when all the best stories and novels have been reprinted in book form since the 1950s? I even wrote an essay about why it’s better to collect the essential anthologies of science fiction than to wade through all the original pulps.

I was born in 1951, so why am I fascinated by the twelve years of science fiction published between 1939 and 1950? On the web I’m constantly meeting old science fiction fans like myself, folks from the Baby Boomer generation, who grew up in the 1960s and fell in love with science fiction they found in libraries that were first published in book format in the 1950s. Most of those stories had originally appeared in the pulp magazines during those years 1939-1950.

I think something psychological is going on. I feel like a biblical scholar who wants to know who wrote The Bible. I’ve gotten tired of modern science fiction. It’s just not the science fiction I grew up reading. I believe I keep returning to old science fiction because I imprinted on it when I was young like a duckling to its mother. It became my religion to explain reality. I know that sounds weird, but I think it’s true. I believe I’m now swimming home like a salmon to where it was first spawned.

If you are young you may never have heard the phrase, “The Golden Age of Science Fiction” – specifically when referring to science fiction published between 1939-1950. And even if you have heard it, you might not know it mainly refers to one magazine and editor, Astounding Science-Fiction and John W. Campbell. Astounding still exists as the magazine Analog Science Fiction and Fact. Campbell changed its name in 1960 to make it more modern, and he had already changed its content significantly in the 1950s, which is why most people consider the Golden Age of Science Fiction to be Astounding in the 1940s. (The phrase, “The Golden Age of Science Fiction” was later recast to mean age twelve when it was realized to be a more universal truth.)

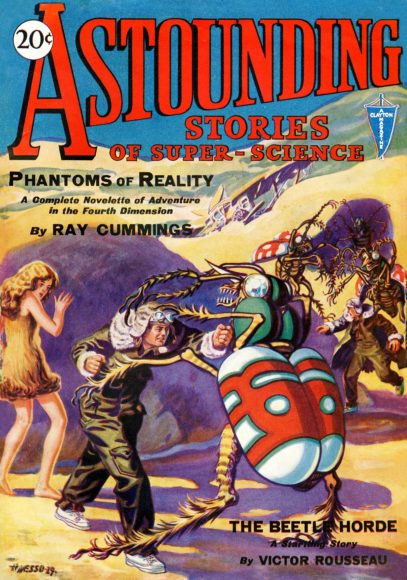

When Astounding first appeared in January 1930, the magazine was called Astounding Stories of Super-Science and edited by Harry Bates. Bates wrote the famous story, “Farewell to the Master” that was made in the 1951 movie, The Day the Earth Stood Still. It struggled to find stories, and few were science fiction. Its goal was to present adventure stories that the emerging science fiction fandom would buy. Just looking at the first cover at the top of this essay tells so much about 1930 science fiction.

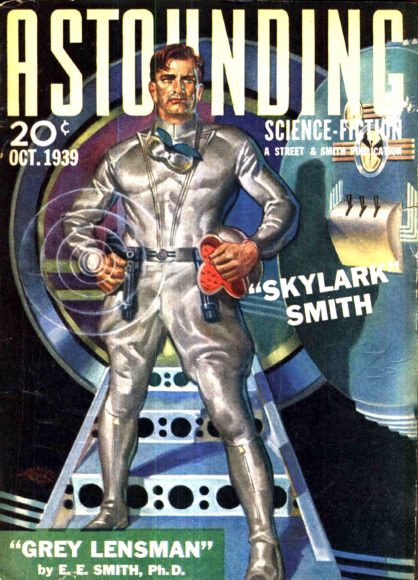

Orlin Tremaine became editor in 1933 when the previous owner became bankrupted and Street & Smith bought out the magazine. Tremaine built up the magazine, bought better science fiction, and gathered a devoted audience. One of his big successes was getting E. E. “Doc” Smith to come over from Amazing Stories so Astounding would have the latest Skylark novel.

John W. Campbell was hired in 1937 to work under Tremaine. By 1938 Tremaine was let go. For a while, Campbell published stories Tremaine had bought. It wasn’t until late 1938 or 1939 that Campbell’s buying decisions changed the course of science fiction. Many of the famous science fiction writers of the 1950s were discovered and nurtured by Campbell in the 1940s.

The nature of science fiction changes almost by the decade. With the arrival of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction in 1949 and Galaxy Science Fiction in 1950, Astounding had significant competition for selling great science fiction. The 1950s were still a great decade for Campbell but his emphasis on ESP, crazy inventions, and crackpot religions got a little weird for some, so most fans consider 1950s Astounding different from the 1940s.

Baby boomers in the 1960s grew up reading the older 1940s and 1950s science fiction while the newer 1960s science fiction came out. Most didn’t know that their copy of The Foundation Trilogy they got when they joined the Science Fiction Book Club was written as a series of short stories for Astounding in the 1940s. A good percentage of famous science fiction “novels” they read in the 1960s were really fix-up novels of related short stories published earlier, such as Slan, More than Human, Pavane, The Martian Chronicles, City, A Case of Conscience, The Dying Earth, Voyage of the Space Beagle, and so on. And many of the actual SF novels published in book form first appeared as serials.

When I study digital scans of old golden age pulp magazines I read the stories the same way readers read them when it first came out. That’s a lot of fun. What’s even more fun is approaching them like a literary professor studying an era of literature. I’m starting to see trends emerge. I’m also seeing ideas that I thought were original in later stories emerge much earlier. Studying science fiction that emerged before NASA existed is quite revealing. Technological events surrounding the A-bomb, H-bomb, Sputnik, Vostok, Mercury, Ranger, Gemini, Mariner, Apollo all impacted the evolving genre.

What fascinates me now is why people in the 1920s and 1930s took to early science fictional concepts. Those concepts were polished in the 1940s science fiction. Then in the 1950s, science fiction bled into the real world when rockets and space travel became real.

A nostalgia for 1940s science fiction began in the 1950s. By the early 1960s, Alva Rogers began writing a fan’s history of Astounding Science Fiction for the fanzine Viper that was published in 1964 as Requiem for Astounding by Advent. Rogers bought his first issue of Astounding at age eleven in 1934 that contained the first part of Skylark of Valeron by E. E. Smith. His book with introductions by the magazine’s first three editors, Harry Bates, F. Orlin Tremaine, and John W. Campbell was a loving history by a first-generation fan.

Another first-generation fan, science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote his memoir Astounding Days in 1989 by recalling how he grew up with the magazine.

Also, from 1989, Alexi and Cory Panshin came out with their Hugo and Locus award-winning The World Beyond the Hill: Science Fiction and the Quest for Transcendence. This large book covers more than just Astounding Science Fiction but spends a significant portion of its time on John W. Campbell and the Golden Age of Science Fiction. This book is currently in print, but just barely. It goes in and out of print. It really deserves more attention than it gets.

The Panshins wrote about science fiction in the way I’m now wanting to study it. But I’m not the only one fascinated with this era. All over the web, I see people my age writing about their love of this older science fiction. Fans have scanned most of the famous pulps from this era and put them on the internet. They work to find and scan all the lesser know pulps and are working back into the dime novel age.

In 2011, Jamie Todd Rubin ran a series on his blog called “Vacation in the Golden Age of Science Fiction.” Later episodes can be found here. Each episode featured a monthly issue of Astounding. I wish Rubin had stuck with the project, but it appears he stopped after 29 issues. I wonder how long I’ll be able to keep up this project?

There’s also a book devoted to Astounding coming out this August. Alec Nevala-Lee has written, Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction. Alec blogged about writing his book at Nevala-Lee’s blog.

I’m sure there are other books about Astounding, Campbell and the Golden Age, but these are the ones I know. I’d be interested in hearing about the others if you know any.

Now I want to write a book about the evolution of science fiction. I’m deeply appreciative that pulp magazine scanners are devoting great amounts of their time and money to preserve all the magazines from the pulp era. Their work is a kind of volunteer librarianship. Their labor of love to digitize the past is reflected in how they constantly work to make better scans. They master Photoshop to remove stains, rust marks, holes, tears, etc. and make those old brown pages look new again. Their efforts allow writers access to the primary documents of pulp magazine history.

I doubt many of you who read this essay will start reading and collecting old pulp magazines. But I am curious how many fans of Astounding still exist. I write this to describe the obsessed efforts of a very small subculture to remember a tiny sliver of American pop culture. If I did write a book, how many would want to read it?

It’s strange how a 1971 wish finally came true in 2018. I would never have imagined back then that computers would let me “own” a complete run of Astounding Science Fiction someday. Nor did I imagine being able to communicate so easily with other fans from around the world who also love those stories.

The internet is becoming the World-Wide Library.

JWH

2018 Andre Norton Award Nominees

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America have announced the nominees for the 2018 Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy

- Exo by Fonda Lee (Scholastic Press)

- Weave a Circle Round by Kari Maaren (Tor)

- The Art of Starving by Sam J. Miller (HarperTeen)

- Want by Cindy Pon (Simon Pulse)

Our congrats to all the nominees.

2017 Nebula Award Nominees

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America have released the final ballot for the 2017 Nebula Award. The noms in the Novel category are:

- Amberlough by Lara Elena Donnelly (Tor)

- The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter by Theodora Goss (Saga)

- Spoonbenders by Daryl Gregory (Knopf; riverrun)

- The Stone Sky by N.K. Jemisin (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- Six Wakes by Mur Lafferty (Orbit US)

- Jade City by Fonda Lee (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- Autonomous by Annalee Newitz (Tor; Orbit UK 2018)

Locus has the complete list of nominees in all categories.

Reading the Pulps #2: “Living Fossil” by L. Sprague de Camp

Read it now: Astounding Science-Fiction February 1939 (from the Luminist League)

You might own “Living Fossil” already in one these anthologies:

- A Treasury of Science Fiction (1948) edited Groff Conklin

- The SFWA Grand Masters, Volume One (1999) edited by Frederik Pohl

Warning: This column contains spoilers.

Let’s imagine we’re a science fiction writer back in the late 1930s. We don’t make much money, so we probably live in a cheap tenement house. There’s no air conditioning, so the windows are open, and the street sounds are pouring in. We have no computer or smartphone, no internet or television. We carefully read the morning and afternoon newspapers, listen to the radio and subscribe to Astounding Science Fiction, Thrilling Wonder Stories, Popular Science, and Scientific American. We often walk to the library in the evening. This is our world of information in 1939.

We’re sitting at the typewriter, smoking a cigarette, planning a story we hope to sell to Astounding Science-Fiction. We want an idea that will wow them and get us the cover. We want to produce the thought variant story. We have a solid knowledge of science fiction published in the pulps back to 1926, and we know the classics like Verne and Wells. Plus, we like to think we’re scientific and visionary.

If you’ve read science fiction short stories from this era you know the variety of wild ideas pitched to science fiction editors. Coming up with something different was essential. Science fiction was mostly idea driven until after the New Wave of the 1960s. Science fiction writers were expected to be as original as research scientists testing a new hypothesis.

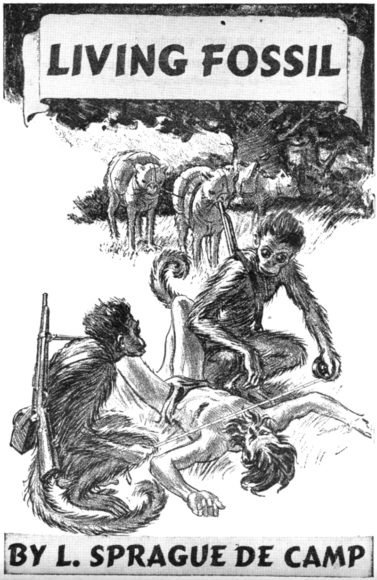

“Living Fossil” by L. Sprague de Camp has not been reprinted very often, and I find that shocking. Anyone seeing the interior illustration above will exclaim, “Oh my god, that’s Planet of the Apes!” But it’s 1939, not 1963 when Pierre Boulle’s Planet of the Apes first appeared in English. How did de Camp get that idea? Was it astoundingly original in 1939, or are there older versions of the same idea in pulps I haven’t read?

Anyone who has read The Time Machine (1995) by H. G. Wells already knows about possible evolutionary descendants of Homo Sapiens. That novella also gave us the meme that death will one day come to both to our species and the Earth. And if you’ve read the brilliant Last and First Men (1930) by Olaf Stapledon then you’ve already entertained that 17 possible future species of humans could exist after us.

Is it so hard to imagine that L. Sprague de Camp asked himself, “What if humans became extinct, how long before another species would become intelligent?” This is one of my favorite science fiction themes: Who comes after us? Clifford Simak imagined intelligent dogs and robots in his lovely fix-up novel, City. Today we assume AI machines will replace us. But have you read the wonderful The World Without Us by Alan Weisman, or seen the television documentaries that were inspired by it? I wrote about them back in 2012. What if self-aware intelligence doesn’t rise up again?

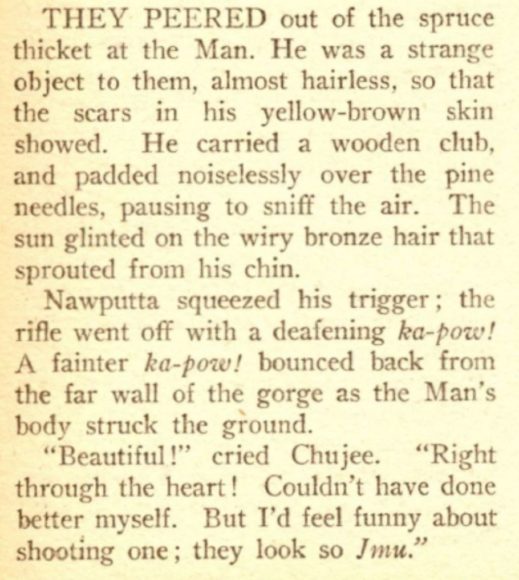

Who comes after humans? “Living Fossil” speculates they could be capuchin monkeys from South America after 10 million years. The story opens with Nawputta, a zoologist and his guide Chujee riding their agoutis exploring northeast North America near Pittsburgh. Ten million years have made a lot of smaller species much larger in their world, and now the agoutis are as large as mules.

Who comes after humans? “Living Fossil” speculates they could be capuchin monkeys from South America after 10 million years. The story opens with Nawputta, a zoologist and his guide Chujee riding their agoutis exploring northeast North America near Pittsburgh. Ten million years have made a lot of smaller species much larger in their world, and now the agoutis are as large as mules.

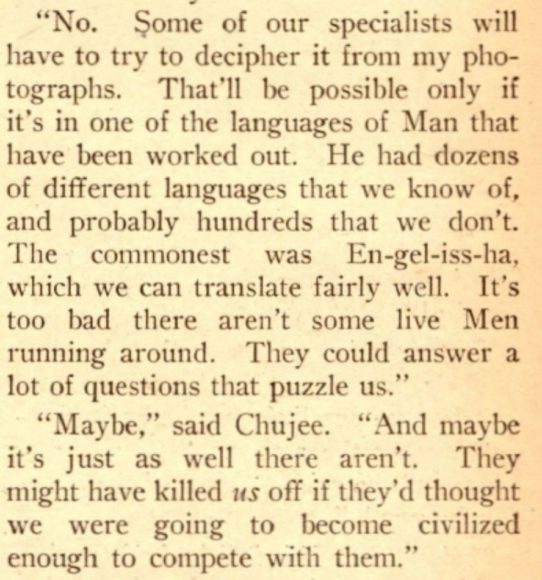

This is a pleasing idea, at least to me. I love to think if humans go extinct life on Earth will go on. De Camp even has his Jmu (the capuchin word equal to human) complain that humans used up all the metals and other resources. As Nawputta and Chujee cross the country looking for new specimens for their museum back home, they speculate about the dead civilization of man. After finding what remains of a large stone with a partial inscription on it, they start speculating:

Notice the part where they wish they could meet a live human? Well, that comes true, but not for a couple days. First, they meet another one of their kind by a campfire, Nguchoy tus Chaw, and he’s none too friendly. This part of the story reminds me of James Fenimore Cooper and his tales about the French and English using the Native Americas. Like Cooper’s stories, there’s all kind of dishonest shenanigans going on by ambitious colonists wanting to exploit the wilderness.

Nguchoy is a timber scout who is doing something shady. Our guys get suspicious of him. After he leaves they head further into the unknown country. Eventually, they find three dead humans, not fossils, with bullet holes in them. They figured Nguchoy shot them. For some reason, the zoologist decides he wants to find and kill a fresh human for a specimen. My friend Mike thought this ruined the story because earlier they had been wishing to find a human to talk to. I assumed they meant city dwelling humans, not humans who had to devolve back to living in caves. Here’s what happens:

This is where de Camp differs from Pierre Boulle. For the rest of the story, which is mainly an adventure narrative about Nawputta and Chujee fleeing for their lives in a territory of hostiles humans who weren’t afraid of their guns. Our sympathy is with the Capuchins. De Camp portrays the humans like Native Americans in old westerns. They are fearless, ferocious, and treacherous. I don’t know if this is ironic or straight. I don’t know if de Camp was being satirical by having monkeys colonize the new world and then treat humans the same way Europeans treated the Native Americans. Or, if the story was to parallel how Cro Magnon killed off the Neanderthal. Or both. In either case, it’s accepted within this story for the monkeys to kill the humans.

In the Planet of the Apes, our perspective is on the side of the humans, and we want them to fight their way back to the top of the evolutionary heap. Boulle plays to our vanity so we want his humans to outwit the evolved apes. In “Living Fossil” de Camp doesn’t take sides but assumes a kind of naturalism where an intellectually advanced species will overcome a less advanced species.

But I have yet another theory. Maybe de Camp wanted to say humans aren’t the divinely chosen, the crown of God’s creation. Science, evolution, and the Enlightenment offer a view of reality where God isn’t needed or wanted. Readers who feel humans are special will object to this story. In fact, the faithful shouldn’t like this story at all, because it says humans aren’t the center of existence, won’t live forever, and are no different from the other animal species. In that sense, I think de Camp is sticking it to our collective egos.

That’s what I love about these old pulp magazine stories. An ordinary writer could have big ideas and get paid a 1/2 cent a word by the top science fiction magazine of the day. Science fiction allows anyone the chance to defy the common belief, the accepted orthodoxy, or even speculate beyond proven scientific knowledge.

Science fiction allowed every writer to become a Darwin, explaining reality in fiction by using their own observations, speculations, and extrapolations. Sure, most science fiction writers came up with craptastic ideas, but so what, some of them were brilliantly imaginative, and often inspired a sense of wonder, at least in adolescent geeky boys of the times.

How would you answer this question today: “Who comes after humans?” Has science fiction already explored all the obvious possibilities? Already, science fiction has suggested endless variations on Superman and mutations. We’ve imagined countless evolved animals and machines taking over. We’ve imagined aliens moving in and kicking us out. But I’m positive, if I keep reading these old pulp magazines, I will find stories that will surprise me.

[I’m surprised “Living Fossil” didn’t get the cover for February 1940.]

JWH

2017 BSFA Shortlist

The British Science Fiction Association has announced the shortlist for the 2017 BSFA Awards.

- The Rift by Nina Allan (Titan US; Titan UK)

- Dreams Before the Start of Time by Anne Charnock (47North)

- Exit West by Mohsin Hamid (Riverhead; Hamish Hamilton)

- Provenance by Ann Leckie (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

See the press release for the complete shortlists in all categories. The winners will be announced at the 69th Eastercon, Follycon, to be held March 30-April 2, 2018 at the Majestic Hotel Harrogate, UK.

2017 Aurealis Awards Finalists

The finalists for the 2017 Aurealis Awards have been announced. The nominees in the SF, Fantasy, and Horror novel categories are:

- Closing Down by Sally Abbott (Hachette Australia)

- Terra Nullius by Claire G. Coleman (Hachette Australia)

- Year of the Orphan by Daniel Findlay (Penguin Random House Australia)

- An Uncertain Grace by Krissy Kneen (Text)

- From the Wreck by Jane Rawson (Transit Lounge)

- Lotus Blue by Cat Sparks (Skyhorse)

- Crossroads of Canopy by Thoraiya Dyer (Tor)

- Gwen by Goldie Goldbloom (Fremantle)

- Cassandra by Kathryn Gossow (Odyssey)

- Godsgrave by Jay Kristoff (HarperCollins)

- Gap Year In Ghost Town by Michael Pryor (Allen & Unwin)

- Wellside by Robin Shortt (Candlemark & Gleam)

- Aletheia by J. S. Breukelaar (Crystal Lake)

- Who’s Afraid Too? by Maria Lewis (Hachette Australia)

- Soon by Lois Murphy (Transit Lounge)

See the official press release for the all the nominees in all categories.

Winners of the 2017 Aurealis Awards will be announced at the Aurealis Awards ceremony during the Easter long weekend as part of the Swancon convention at the Pan Pacific hotel, Perth.

Reading the Pulps #1: “Quietus” by Ross Rocklynne

Original Source: Astounding Science-Fiction September 1940 (link to Luminist.org where you can find old issues of Astounding Science Fiction)

In Anthologies you might own:

- Adventures in Time and Space (1946) ed. Healy & McComas

- The Great SF Stories 2: 1940 (1979) ed. Asimov & Greenberg

- The World Turned Upside Down (2005) ed. Flint, Baen, & Drake

WARNING: This column contains spoilers

I don’t remember reading any Ross Rocklynne before I started reading The Great SF Stories edited by Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg. From the 1940 volume, I read “Into the Darkness,” Rocklynne’s impressive science fiction philosophical fairy tale that felt inspired by the writings of Olaf Stapledon. I probably read “Quietus” before in my youth because I loved the Adventures in Time and Space anthology, but I’ve totally forgotten it.

I’m undergoing a reading renaissance in science fiction in my retirement years that is as exciting as when I first discovered science fiction at age twelve. But it’s for a different reason. This time around, I’m thrilled by the history of science fiction and how its ideas, themes, and concepts evolved. And because many pulp magazines from that era are available online I can study them. I love trying to imagine how readers back then (whatever the date on the magazine) felt about the story with their then current knowledge. Our culture is so filled with science, and our pop culture so filled with science fiction, it’s hard to comprehend when their science fictional ideas were fresh and original.

“Quietus” begins with “The creatures from Alcon saw from the first that Earth, as a planet, was practically dead; dead in the sense that it had given birth to life, and was responsible, indirectly, for its almost complete extinction.”

Tark and Vascar, two intelligent beings evolved from birds on the planet Alcon, are on an exploration trip. Tark is male, Vascar is female. On their way home, they spot Earth. It appears that an asteroid has hit our world and only a small patch of green is left on the globe. This 1940 story grabbed my attention right away, reminding me of an avian version of Star Trek.

The action next cuts to a naked young man on Earth killing and eating a rabbit raw. We quickly learn that Tommy survived the asteroid apocalypse as a child, becoming a feral kid living alone. He is now a young adult and his language skills are limited to that of childhood. Tommy has a crow companion named Blacky that parrots his words, and often saying phrases before Tommy, anticipating his reactions.

The action next cuts to a naked young man on Earth killing and eating a rabbit raw. We quickly learn that Tommy survived the asteroid apocalypse as a child, becoming a feral kid living alone. He is now a young adult and his language skills are limited to that of childhood. Tommy has a crow companion named Blacky that parrots his words, and often saying phrases before Tommy, anticipating his reactions.

Tommy is driven by two kinds of hunger. One he knows for food, but the second he doesn’t understand until he finds the trail of a young woman. At this point, I worried that Rocklynne was going to give us one of those cliché Adam and Eve endings that used to show up in science fiction.

The story switches back to Tark and Vascar who spot Tommy and his quest with their viewer. They argue about what to do. Vascar wants to assume the crow is the intelligent species because it rides on Tommy’s shoulders and speaks commands to him. Tark wants to keep an open mind, assuming either could be the dominant species. There’s some nice speculation about what happened to the Earth, determining its future, and the proper approach to make when contacting the intelligent species of the planet. Tark is like Mr. Spock, analytical. Vascar is more like Kirk, impulsive.

The story jumps back and forth from Tommy’s point of view to those of the Alconians.

Eventually, Tommy gets closer to the elusive female. We start to feel for him and want them to meet and mate. Whenever he gets close, she panics at the sight of the crow and takes off again. At one point, Tommy gets mad at Blacky and starts to throw stones at him, when:

“It’s all your fault, Blacky!” Tommy raged. He picked up a rock the size of his fist. He started to throw it, but did not. A tiny, sharp sound bit through the air. Tommy pitched forward. He did not make the slightest twitching motion to show that he had bridged the gap between life and death.”

WTF!?! This is cold.

Rocklynne just killed our sympathetic character. That shocked me. I had already had two assumptions about where the story might go. First, I thought Tommy and the girl would mate and the Alconians would discover the humans were the intelligent species. Then they would think about how to protect the last pair of humans surviving on Earth. Or, I thought Tark and Vascar might take them away as a breeding pair to their planet. I wasn’t expecting them to do something we’d do.

Tark was furious at Vascar for killing the human. He says, “You have killed their species.” They eventually check out the crow, but it eludes them, and they begin to assume it’s not intelligent. Eventually, they return to their ship and head home to Alcon. For us, this is a story about the end of humanity.

After a bit of contemplation, I decide I really like this ending, even though it shocked me. I admired Rocklynne for having the guts to go against convention. This story is cold like “The Cold Equations” by Tom Godwin (Astounding Science Fiction, 1954).

Which brings me to concepts and themes. Besides interstellar travel, alien cultures, and space exploration teams, the story combines post-apocalyptic survival with the last men on Earth themes. Two of my favorites. Generally, science fiction offers hope we’ll survive, but occasionally, it writes our ending. Somehow science fiction has claimed stories about the first and last men as its territory. Two stories I recently read from 1939 were about Neanderthals. And “Quietus” is at least the second story I read in the last couple weeks about our end. The other was “Living Fossil” by L. Sprague de Camp.

But there’s another theme here that’s quieter. I’m guessing between 1926-1946 science fiction was ahead of the game when it came to promoting space travel ideas, but I’m not sure. As I read pulp fiction stories I’m paying attention to ideas and trends. I’m pretty sure the concept of spacesuits were developed in science fiction before they were theorized by scientists. But what about the ideas of space navigation, orbiting planets, escape velocity, airlocks, landings, interplanetary and interstellar travel, etc. We’ve grown up knowing all kinds of things about space travel, but I’m guessing those ideas didn’t exist before a certain point in time, and maybe science fiction introduced them to the public before scientists.

At one-point Rocklynne said, “The ship made a slow circuit of Earth” and I wondered when science and science fiction would start saying “going into orbit” or “achieving orbit” or some other common phrase we use today? That got me to thinking. This is 1940, way before Americans heard about V-1s and V-2s, but Robert Goddard had been working with rockets since the 1910s. On 1/12/20 The New York Times ran a front-page story, “Believes Rocket Can Reach Moon” about Goddard’s work. In 1924 Goddard published an article in Popular Science “How My Speed Rocket Can Propel Itself in Vacuum.” Goddard’s rockets didn’t look like rockets then.

Wikipedia says Goddard was often misunderstood and mocked. Goddard didn’t achieve liquid fuel flights until 1926. Lindbergh got interested in Goddard, and then the public started noticing him more in 1929 and 1930. Throughout the 1930s Goddard continued to develop rockets that began to look like modern rockets (cylinder with fins). Goddard’s work was probably well known by this 1940 story. Here’s a 1924 article about rocketry in Popular Science that mentions Goddard and other rocket pioneers.

It’s hard to comprehend the public’s mindset of the past. Their science fiction came down to us, but not their popular science books. Yesterday I discovered I could read old issues of Popular Science online. These old issues are very revealing. In fact, they can be more fun than reading the old pulps.

My plan for this column is to discuss the stories I read and try to figure out how science fiction and science fictional ideas evolved in the popular conscience of the day.

JWH

The 2017 Bram Stoker Awards Final Ballot

The Horror Writers Association has announced the 2017 Bram Stoker Awards Final Ballot. The finalists for Superior Achievement in a Novel are:

- Ararat by Christopher Golden (St. Martin’s Press)

- Sleeping Beauties by Stephen King and Owen King (Scribner)

- Black Mad Wheel by Josh Malerman (Ecco)

- I Wish I Was Like You by S. P. Miskowski (JournalStone)

- Ubo by Steve Rasnic Tem (Solaris)

See the official press release for the nominees in all categories.

The presentation of the awards will occur during the third annual StokerCon, to be held March 1st-4th at the historic Biltmore Hotel in Providence, Rhode Island.

Full Details

Full Details

BEST SCIENCE FICTION NOVEL

BEST SCIENCE FICTION NOVEL

BEST FANTASY NOVEL

BEST FANTASY NOVEL

BEST HORROR NOVEL

BEST HORROR NOVEL