Outside the Norm: Announcing the Outside the Norm Reading Group

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

Over in the forum, several of us have been putting together an Outside the Norm Reading Group for the remainder of the year and continuing into the next. It will function much like a book club. We will read one book a month and will spend at least the first week of the following month discussing the book in the group. Emil has offered this format for discussion:

Over in the forum, several of us have been putting together an Outside the Norm Reading Group for the remainder of the year and continuing into the next. It will function much like a book club. We will read one book a month and will spend at least the first week of the following month discussing the book in the group. Emil has offered this format for discussion:

- Initial impression of the book

- Themes

- Particular theme that impressed

- Favorite scene/moment, etc.

We have planned books through next January, but we would love for this to continue longer and get your input for future books. We envision this as a fluid "book club" and hope that people will be able to join (and leave) according to their interest in the books we will discuss each month.

The July book is Victor Pelevin’s Omon Ra. We will discuss it during the first week of August. It is only 153 pages, so it will be easy to catch up this month.

The remaining schedule is:

- August: Ben Okri, The Famished Road

- September: José Saramago, Blindness

- October: Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita

- November: Angela Carter, Nights at the Circus

- December: Yevgeny Zamyatin, We

- January: Doris Lessing, Memoirs of a Survivor

Remember: We will discuss each book during the first week of the following month.

Feel free to offer up suggestions of science fiction, fantasy and horror books that you feel are "outside the norm," which we have been defining as books by women, persons of color, or non-US/UK authors. We have been using the Guardian list as a guide, but we certainly not limited to those books.

Please join us in the forum!

Outside the Norm: Dubravka Ugresic’s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

I began this Outside the Norm blog because I wanted to challenge myself to read more books by women, persons of color and nationalities other than American and British. So far I’ve read canonical authors like Le Guin and those who are starting to make a name in the F and SF world like Nnedi Okorafor. I’m also beginning to see this title as a license to write about others whose speculative work is just outside the parameters of the lists and awards compiled here. This blog is about one of those books, Dubravka Ugresic‘s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg.

This book first came to my attention because it won the 2010 James Tiptree, Jr. Award. The Tiptree’s mission, as stated on its website, is to honor a science fiction or fantasy work "that expands or explores our understanding of gender" and is given each year at WisCon. Ugresic is a Croatian academic who was forced into exile by a nationalist government. Most of her books and collections of essays are political in nature. This book was nominated for the Man Booker International Prize, so, as you can see, she’s not an author whose name would typically end up on a list of the year’s best fantasy writers. Yet, her use of myth in this book placed the book in the realm of fantasy for some readers like the Tiptree jury. The book is a three-part engagement with Baba Yaga, the witch-like character of Slavic folklore.

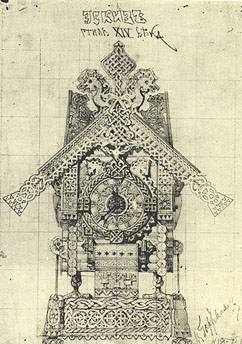

I confess that all I really knew about Baba Yaga came through an introduction via the prog rock CD Pictures at an Exhibition (1972) by Emerson, Lake and Palmer. That group had recorded a suite by the Russian composer, Modest Mussorgsky, which Mussorgsky had based on an art exhibition by the Russian artist Viktor Hartmann. (For more about Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, check out the music and new images here.) One of the images that inspired subsequent songs by Mussorgsky and Emerson, Lake, and Palmer was "The Hut of Baba Yaga." This song sent my younger self off to research Baba Yaga.  I learned that Baba Yaga lived in a giant hut that walked around on huge chicken legs. Much like the witches in Grimm’s fairy tales, she lured children to her forest hut and ate them. She flew around in a mortar, using the pestle like an oar, and used a broom to sweep away her tracks. Here you can see her connection to the more western witches on broomsticks. However, no previous knowledge of Baba Yaga is required to read this book because the reader is slowly educated through the author’s three sections. This structure and strategy is what makes this book so interesting and made me decide to write this review.

I learned that Baba Yaga lived in a giant hut that walked around on huge chicken legs. Much like the witches in Grimm’s fairy tales, she lured children to her forest hut and ate them. She flew around in a mortar, using the pestle like an oar, and used a broom to sweep away her tracks. Here you can see her connection to the more western witches on broomsticks. However, no previous knowledge of Baba Yaga is required to read this book because the reader is slowly educated through the author’s three sections. This structure and strategy is what makes this book so interesting and made me decide to write this review.

The short prologue "At First You Don’t See Them…" unapologetically tells the reader that this book will be about old women:

Sweet little old ladies. At first you don’t see them. And then, there they are, on the tram, at the post office, in the shop, at the doctor’s surgery, on the street, there is one, there is another, there is a fourth over there, a fifth, a sixth, how could there be so many of them all at once? (2)

The invisibility of these "little old ladies" is a direct comment on society’s tendency to dismiss the elderly and their needs and forget about their continued usefulness to society. Ugresic’s book goes beyond this generalization of invisibility and takes on the ways that our view of "little old ladies" is often based on gender stereotypes created by earlier patriarchal societies, especially crone figures like the Baba Yaga.

The first section "Go There – I Know Not Where – and Bring Me Back a Thing I Lack" has no speculative fiction elements. It is written in the first person. The narrator is a famous author who frequently returns to her hometown of Zagreb, Croatia to take care of her elderly mother. Her widowed mother has had a stroke: she uses a walker and her language was affected so that she often uses the wrong word. This leads to some humorous conversations between mother and daughter:

The first section "Go There – I Know Not Where – and Bring Me Back a Thing I Lack" has no speculative fiction elements. It is written in the first person. The narrator is a famous author who frequently returns to her hometown of Zagreb, Croatia to take care of her elderly mother. Her widowed mother has had a stroke: she uses a walker and her language was affected so that she often uses the wrong word. This leads to some humorous conversations between mother and daughter:

"Bring me the…."

"What?"

"That stuff you spread on bread."

"Margarine?"

"No."

"Butter?"

"You know it’s been years since I used butter!"

"Well, what then?"

She scowls, her rage mounting at her own helplessness. And then she slyly switches to attack mode.

"Some daughter if you can’t remember the bread spread stuff!"

"Spread? Cheese spread?"

"That’s right, the white stuff," she says, offended, as if she had resolved never to again utter the words ‘cheese spread.’" (11)

I think my favorite one is when she asked for "the biscuits, the congested ones," instead of the digestive ones. (11-12)

We learn that the mother is Bulgarian and came to Croatia as a young wife. Some of her most treasured curios represent Bulgaria or are mementos of her early life. The daughter decides that she wants to visit Bulgaria as her mother’s bedel: "[c]enturies ago the wealthy would send someone else off on the hajj or the army in their stead as a bedel, a paid surrogate" (41). The daughter wants to bring back pictures of her mother’s city so that her mother can remember her youth. She enlists the help of a Bulgarian fan, Aba, who had written the author earlier, wanting to visit her in Croatia. Aba, a student in folklore, was in Croatia on an academic fellowship. The author was unable to meet Aba but facilitated a relationship between her mother and Aba, as fellow Bulgarians. The mother and Aba hit it off, so the daughter later arranges for Aba to accompany her while in Bulgaria. Her best-laid plans of "bedelship" go astray: she finds her mother’s hometown a victim of the communist and post-communist economies and finds the locations of her mother’s home and school changed and worn down; she also finds Aba annoying because the young fan wants to quote the author’s writing back to her. Thus, this first section is a look at aging, relationships and post-communist Eastern Europe.

We learn that the mother is Bulgarian and came to Croatia as a young wife. Some of her most treasured curios represent Bulgaria or are mementos of her early life. The daughter decides that she wants to visit Bulgaria as her mother’s bedel: "[c]enturies ago the wealthy would send someone else off on the hajj or the army in their stead as a bedel, a paid surrogate" (41). The daughter wants to bring back pictures of her mother’s city so that her mother can remember her youth. She enlists the help of a Bulgarian fan, Aba, who had written the author earlier, wanting to visit her in Croatia. Aba, a student in folklore, was in Croatia on an academic fellowship. The author was unable to meet Aba but facilitated a relationship between her mother and Aba, as fellow Bulgarians. The mother and Aba hit it off, so the daughter later arranges for Aba to accompany her while in Bulgaria. Her best-laid plans of "bedelship" go astray: she finds her mother’s hometown a victim of the communist and post-communist economies and finds the locations of her mother’s home and school changed and worn down; she also finds Aba annoying because the young fan wants to quote the author’s writing back to her. Thus, this first section is a look at aging, relationships and post-communist Eastern Europe.

The second section, "Ask Me No Questions and I’ll Tell You No Lies," continues the theme of playing with language that Ugresic began in the first section. One character, Beba, says the wrong word when nervous which leads her to say things like "Have a nice lay," when she means to say "Have a nice day." This playfulness continues throughout section two whose genre is closest to magical realism. It is full of improbable happenings and unbelievable coincidences that the characters never seem to notice. Also all the characters seem more symbolic and less real. Each seems like an archetype for an idea that I don’t quite grasp. (This is not a criticism. I didn’t feel lost at all.)

In this section, three old Croatian ladies, Pupa, Kukla, and Beba, ranging in age from sixty to eighty (or maybe more), visit the Wellness Centre, a spa in the Czech Republic. Their only connection to section one is that Pupa is mentioned there as one of the mother’s friends. Most of the men that the women meet in this section are part of the beauty and anti-aging industry. Mr. Shaker is an American who owns a business that sells pills, potions, and remedies, "bearing the food label supplement" (92). His American market is collapsing because reports are emerging that his remedies "pump up muscles" but "reduced potency" (93). So now he is looking into the "post-communist market" (93). Dr. Topolanek, the owner of the Wellness Centre, makes his living via "human vanity," selling his theory of longevity as well as spa treatments and massages (98). Finally, the old women meet Mevludin, a young Bosnian refugee, who works as a masseur at the Centre. The women spend a fantastic six days at the Centre. The endings are "happy" for Pupa, Kukla, and Beba, but they each travel from the spa into unknown worlds and challenges.

Here Ugresic criticizes the cult of youth and beauty. Her Croatian perspective is interesting because in Eastern Europe this cult is directly tied to post-communist capitalism. Dr. Topolanek sees his generation’s revolution as an internal one, one that allows people to change their bodies to whatever they want them to be. One of the best moments of this section shows Beba, who has been portrayed as an airhead up to this point, relaxing in a bath of warm chocolate (one of the therapeutic treatments) and musing upon the reproduction of Renior’s Woman with Parrot, hung on the wall. Beba’s thoughts carry us through an art history lecture that connects parrots with women’s sexuality in western art. This is a fun (and unexpected) tangent, but again illustrates why the book appealed to the Tiptree jury.

Here Ugresic criticizes the cult of youth and beauty. Her Croatian perspective is interesting because in Eastern Europe this cult is directly tied to post-communist capitalism. Dr. Topolanek sees his generation’s revolution as an internal one, one that allows people to change their bodies to whatever they want them to be. One of the best moments of this section shows Beba, who has been portrayed as an airhead up to this point, relaxing in a bath of warm chocolate (one of the therapeutic treatments) and musing upon the reproduction of Renior’s Woman with Parrot, hung on the wall. Beba’s thoughts carry us through an art history lecture that connects parrots with women’s sexuality in western art. This is a fun (and unexpected) tangent, but again illustrates why the book appealed to the Tiptree jury.

The third section continues on this scholarly tone. It begins with a letter that Dr. Aba Bagay, presumably the Bulgarian folklore student in section one, writes to an unknown editor who has asked her to read a manuscript and "explicate the correspondences between [the] author’s text and the myth of Baba Yaga" (239). The remainder of the section is her response, "Baba Yaga for Beginners," which discusses symbols related to Baba Yaga, supporting these with quotations from Eastern European myths and legends as well as quotations from scholars in the field, such as Maria Gimbutas and Marina Warner. Aba includes discussions of Baba Yaga’s name, her connection with witches and cannibalism and all her symbols, such as the hut, the mortar and pestle, birds and eggs. After each part, Aba provides "Remarks" that analyze the fictional author’s text in reference to the topic she just explained.

The surprising part is that the text that Aba is reading and commenting upon is made up of the two sections we just read. So, effectively, we have an author in the guise of an academic analyzing the book she just wrote. Ugresic shows her readers all of the Baba Yaga symbols and allusions that she included and they missed (at least many were missed on my part). For example, following her discussion of the hut, Aba writes:

Returning home, your author returns to the maternal ‘hut’ and repeats the initiation rite for the nth time. She must respect the law of Baba Yaga’s hut, otherwise Baba Yaga will eat her up. (263)

I’ve tried to find some other examples, but many of them give away too much about the plot. Just trust me; I couldn’t wait to finish each part so that Aba could connect my new knowledge of Baba Yaga to the previous plots. This set up makes for a very rich reading experience. I’ve never read a book before that taught its readers how to read it. I enjoyed being educated about the myth of Baba Yaga in this unorthodox manner.

I’ve tried to find some other examples, but many of them give away too much about the plot. Just trust me; I couldn’t wait to finish each part so that Aba could connect my new knowledge of Baba Yaga to the previous plots. This set up makes for a very rich reading experience. I’ve never read a book before that taught its readers how to read it. I enjoyed being educated about the myth of Baba Yaga in this unorthodox manner.

The ending brings in an element of the supernatural and that, along with the heavy dose of myths and folklore in section three and the magical realism of section two, shows me why this book was nominated for and won the Tiptree Award, even though at first glance this is not an obvious candidate. I found this book a very pleasurable read because I was continually intrigued about the way the story was being told.

Outside the Norm: Karen Lord’s Redemption in Indigo

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

Nalo Hopkinson calls Karen Lord‘s Redemption in Indigo "[t]he impish love child of Tutuola and Garcia Marquez." I have never read Tutuola, but I immediately understood Hopkinson’s comment when I started reading the book and thought it was a mixture of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. So, no matter what authors or book the readers use for their analogies, the most compelling feature of Redemption in Indigo is its ability to mix New World magical realism with Old African folktales, in her case the world of Barbados and its undying spirits, the djombi, with the Senegalese folktales of Anansi, the spider trickster god.

Nalo Hopkinson calls Karen Lord‘s Redemption in Indigo "[t]he impish love child of Tutuola and Garcia Marquez." I have never read Tutuola, but I immediately understood Hopkinson’s comment when I started reading the book and thought it was a mixture of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. So, no matter what authors or book the readers use for their analogies, the most compelling feature of Redemption in Indigo is its ability to mix New World magical realism with Old African folktales, in her case the world of Barbados and its undying spirits, the djombi, with the Senegalese folktales of Anansi, the spider trickster god.

The book begins by setting up the narrative as a tale told by a storyteller: an "I" who is talking to a group of "yous," of which the reader is one. The story playfully ends with the storyteller’s solicitations:

"it is terribly dry and thirsty work, speaking these lives into the dusty air of the court, speaking for you to hear and ponder and judge. Perhaps, if you would be so kind as to contribute, I could purchase some refreshments now, find a place to rest my head later, and return to you on the morrow with my voice and memory and strength restored. Please, ladies and gentlemen, if you have at all enjoyed my story, be generous as the pot goes around, and do come back again soon." (182)

He similarly begins the epilogue by telling us that he has been "authorised" to tell us more. This narrative method enhances the folktale elements because it provides an inventive way to fill in cultural background for readers who probably aren’t familiar with the ways of the greater and lesser djombi and the other supernatural beings they encounter.

Our storyteller begins with the story of Paama, who’s left her husband, Ansige, and returned with her family to her village. Paama leaves her husband because of his gluttony. He was "not an epicure, but a gourmand," his every thought and action controlled by his desire for food and his only worry about his next meal (7). When Ansige finally arrives at the village to beg her to return to him, his exploits demonstrate his origin in East African folktale characters. His gluttony gets him into all kinds of trouble from which Paama has to rescue him. However, Paama has bigger problems than her husband. Before Ansige even arrives at her village, two djombi have decided to steal Chaos from another djombi and give it to Paama, which will give her immense power. Just as Paama starts to understand her unwanted power, the indigo djombi, the original wielder of Chaos, has tracked his power to her village.

The relationships Lord forges between the supernatural beings and humanity elevate the plot beyond the typical tale of a heroine who must fight to save her people and their way of life. The supernatural beings are complex characters who are dissatisfied with the way their identities often limit their roles. The storyteller speaks about the indigo djombi:

The djombi are like the human creatures they meddle with, apt either to great evil or great good, and sometimes they switch sides.

This one was the unknown danger. He had switched sides. He had started with benevolence, with the belief that there is the fine potential in humankind waiting only to be tapped. He now viewed the whole stinking breed as a pest and a plague. (58)

As a symbol of his change from benevolent to malignant, the djombi changes his color to indigo, "a stark and utter setting apart that provoked as much of horror as of awe" (59). Another supernatural being, the Trickster, who usually appears in the form of a spider, changes in the opposite direction. He began "delighting in the frailties of humans and exploiting those weaknesses for his own entertainment" but became bored with "playing the same old practical jokes" (102). After a while he started "turning people to situations of mutual benefit rather than merely gratifying his own sense of the ridiculous" (102). The pleasure in this novel is observing these beings as they learn about their omnipotence and start to interact with Paama and her community in a meaningful way. The ending, while somewhat predictable, gives the readers the happy endings and the redemptions that the title tells them to expect.

As a symbol of his change from benevolent to malignant, the djombi changes his color to indigo, "a stark and utter setting apart that provoked as much of horror as of awe" (59). Another supernatural being, the Trickster, who usually appears in the form of a spider, changes in the opposite direction. He began "delighting in the frailties of humans and exploiting those weaknesses for his own entertainment" but became bored with "playing the same old practical jokes" (102). After a while he started "turning people to situations of mutual benefit rather than merely gratifying his own sense of the ridiculous" (102). The pleasure in this novel is observing these beings as they learn about their omnipotence and start to interact with Paama and her community in a meaningful way. The ending, while somewhat predictable, gives the readers the happy endings and the redemptions that the title tells them to expect.

Because Karen Lord explores these big ideas of omnipotence and redemption in a Caribbean setting, her book has garnered attention outside the F/SF community. It won the 2008 Frank Collymore Award, given to an unpublished Barbadian work. It was also nominated for the 2011 Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. Back in the F/SF world, the book was a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and won the 2011 Mythopoetic Award and the 2011 Crawford Award for the best fantasy novel by a new writer. For more on its awards, see Karen Lord’s interview with Chesya Burke.

The adjective that comes to mind when I think about Redemption in Indigo is fresh. The story has recognizable elements–heroes, gods meddling with the affairs with humans, mythological characters and folktales–but Lord uses these elements in unexpected ways, except for the ending, which is satisfying in its predictability. Her style of fantasy is smart, inventive, and innovative. I look forward to Lord’s next book.

Outside the Norm: Nnedi Okorafor’s Zahrah the Windseeker and The Shadow Speaker

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

When I started thinking about authors I would read for this series, Nnedi Okorafor was at the top of my list. I started with two of her young adult novels, Zahrah the Windseeker and The Shadow Speaker because they were available in my college library. Both of these novels feature female protagonists who are about fourteen years old. Each girl has a special magical power and learns to use her power when she embarks upon a quest. As such, these are coming-of-age narratives that show how the girl, who is different, who is teased for being different, comes into her own and learns of her own strength and self-worth. This seems to me to be what many YA novels do; however, I did not really read YA novels when I was a “YA” (except that I had a great obsession with The Hardy Boys mysteries), so I am far from an expert.

When I started thinking about authors I would read for this series, Nnedi Okorafor was at the top of my list. I started with two of her young adult novels, Zahrah the Windseeker and The Shadow Speaker because they were available in my college library. Both of these novels feature female protagonists who are about fourteen years old. Each girl has a special magical power and learns to use her power when she embarks upon a quest. As such, these are coming-of-age narratives that show how the girl, who is different, who is teased for being different, comes into her own and learns of her own strength and self-worth. This seems to me to be what many YA novels do; however, I did not really read YA novels when I was a “YA” (except that I had a great obsession with The Hardy Boys mysteries), so I am far from an expert.

What amazes me is the variety of plots that YA authors devise to illustrate this common theme. As proof of this, the young heroes Zahrah Tsami and Ejii Ugabe (who is the protagonist of The Shadow Speaker) demonstrate different strengths and weaknesses as they experiment with their powers; the goals of their quests are nothing alike; and the plots are not formulaic and are paced quite differently from each other. Both Ejii and Zahrah are metahumans (or in the older lingo, dada). Ejii’s skills are apparent from the beginning of the novel, while Zahrah learns what her talents are during the course of her narrative. Zahrah is born with dadalocks, which seem to be dreadlocks that have vines incorporated in them. Here’s what Zahrah says about being born dada:

“To many, to be dada meant you were born with strange powers. That you could walk into a room and a mysterious wind would knock things over or clocks would automatically stop; that your mere presence would cause flowers to grow underneath the soil instead of above. That you caused things to rebel or that you would grow up to be rebellious yourself! And what made things even worse was that I was a girl, and only boys and men were supposed to be rebellious. Girls were supposed to be soft, quiet, and pleasant.” (Zahrah the Windseeker viii).

One great thing that these books have in common is a complex magical world that engenders these metahumans, which is what I want to discuss in this blog. According to Okorafor’s website, Who Fears Death and her other YA novel, Akata Witch are set in the same world.

Okorafor’s literary setting contains several parallel worlds, Earth, Lif, Ginen, Ngiza, and Agonia (The Shadow Speaker 301). Zahrah the Windseeker is set in the village of Kirki in the Ooni Kingdom, which is in Ginen. In this novel, few characters know that there are parallel worlds. For Zahrah and her friend, Dari, Earth is only a myth, until they meet Nsibidi who claims her mother is from Earth. The Shadow Speaker occurs later in the timeline because, in Ejii’s Earth, people are able to move between parallel worlds. Ejii’s quest requires her to leave her Nigerien village of Kwàmfà and to travel to the Ooni Kingdom in Ginen. The shadows who whisper to her have told her that only her presence at the multi-world meeting of the Golden Dawn can stop the other parallel worlds from declaring war against Earth.

The year of Ejii’s adventure is 2070. She lives after the Great Change, a series of events that engendered both magic and mutants on Earth. The Great Change is the “result of nuclear and Peace Bombs being dropped all over the earth. The Peace Bomb was the tool of an enviro-militant group called the Grand Bois, headed by a Haitian man named Dieuri [who], himself, was responsible for crossing science and magic and creating the Peace Bomb, a weapon consisting of airborne biological agents meant to counteract the effects of nuclear missiles” (55). Besides shadow speakers, who can listen to the shadows, interpret the thoughts and feelings of other sentient beings, and communicate with some of animals and non-humans, there are windseekers, like Zahrah, who can fly. Other metahumans that receive less attention in Okorafor’s books are shape-shifters, faders, firemolders, rainmakers and metalseekers. Many animals in her worlds can speak, such as Onion, Ejii’s camel:

The year of Ejii’s adventure is 2070. She lives after the Great Change, a series of events that engendered both magic and mutants on Earth. The Great Change is the “result of nuclear and Peace Bombs being dropped all over the earth. The Peace Bomb was the tool of an enviro-militant group called the Grand Bois, headed by a Haitian man named Dieuri [who], himself, was responsible for crossing science and magic and creating the Peace Bomb, a weapon consisting of airborne biological agents meant to counteract the effects of nuclear missiles” (55). Besides shadow speakers, who can listen to the shadows, interpret the thoughts and feelings of other sentient beings, and communicate with some of animals and non-humans, there are windseekers, like Zahrah, who can fly. Other metahumans that receive less attention in Okorafor’s books are shape-shifters, faders, firemolders, rainmakers and metalseekers. Many animals in her worlds can speak, such as Onion, Ejii’s camel:

“Onion was not like other camels. He was one of the few who could speak; one did not have to be a shadow speaker or any other type of metahuman to understand him. After the Great Change, Onion had realized that he had a bulge near the top of his long neck—a large, developed voice box. He’d been hearing human beings speak all his short life, for he was just a calf. It was not hard for him to do the same.” (The Shadow Speaker 74).

Like Ejii, Zahrah is able to converse with some other animals because of her dada powers.

In both cultures, metahumans are the minority and are feared by many people who say they bring bad luck or are evil creatures. The acceptance of metahumans seems more “progressive” in The Shadow Speaker, perhaps because the Great Change causes more of them. Ejii has two friends who are shadow speakers and together they train with an adult shadow speaker. On the other hand, Zahrah’s fear of her emerging abilities to levitate and fly and her desire to hide these abilities create the tragedy that brings about her quest into Ooni’s Forbidden Greeny Jungle.

Technology plays an important role in both stories. The way that Okorafor constructs technology in each parallel world is true to her overall portrayal of each. Ejii carries an e-legba, which seems to be like an iPad. The internet became immortal after the Great Change, continuing to work without either “power or maintenance” (The Shadow Speaker 93). Zahrah’s Ginen is a plant-based world. Zahrah has a floral computer:

“My father had given me the CPU seed when I was seven years old, and I had planted and taken care of it all by myself…. Its light green pod body was slightly yielding, and the large traceboard leaf fit on my lap like a part of my own body…. The computer would pull energy from my body heat, and I’d link a vine around my ear so that it could read my brain waves. It would grow in size and complexity, as I grew.” (Zahrah the Windseeker 37-38)

Many of the buildings are also engineered from plants. For example, the library in Zahrah’s village is a five-story building grown from a glassva, a transparent plant. At this library, Zahrah and her friend Dari checkout a digi-book, The Forbidden Greeny Jungle Field Guide, that accompanies her upon her quest. Okorafor has written a short story about a set of adventurers who contribute to this book and are looking for a rare wild CPU plant. (You can find “From the Lost Diary of Treefrog7” here.)

These novels are fun and exciting reads. As I read, I wished that I knew more about West African culture, mythology, and folklore. I felt as if I was missing out on some interesting nuances. For example, what am I missing when I read Ejii’s mother is New Tuareg and her father was Wodaabe? I learned a lot about these tribes from the links and was able to see how Okorafor used tribal traits of the Tuareg for characterization and plot. However, I feel that the stories of their stormy relationship is intended to be a metaphor of Niger, but I’m not well informed enough in Nigerien or West African history to understand.

These novels are fun and exciting reads. As I read, I wished that I knew more about West African culture, mythology, and folklore. I felt as if I was missing out on some interesting nuances. For example, what am I missing when I read Ejii’s mother is New Tuareg and her father was Wodaabe? I learned a lot about these tribes from the links and was able to see how Okorafor used tribal traits of the Tuareg for characterization and plot. However, I feel that the stories of their stormy relationship is intended to be a metaphor of Niger, but I’m not well informed enough in Nigerien or West African history to understand.

If I have any criticism of the books, it is that the conclusions leave you wanting more. I feel the ending of The Shadow Speaker was too abrupt. Ejji’s return home leaves open some questions about what happened in Kwàmfà while she was away. Zahrah the Windseeker has a much more extended ending, but Zahrah and Dari’s encounter with Nsibidi, a mysterious windseeker from Earth leaves the ending open. Both endings almost seem as if they are setting up sequels. However, Okorafor’s publishing history does not seem to indicate that she will revisit these characters even though she is revisiting this world in her more recent books, which I am now even more anxious to read. The conference that Ejii attends in Ginen gives us a glimpse of the peoples who live in the some of the other parallel worlds. I hope Okorafor decides to explore Lif, Ngiza, and Agonia as well.

I think some readers will not like Okorafor’s world as much as I do. She does not always explain things, and I’m sure if I looked I could find contradictions in the ways that the magic functions. However, I can very willingly suspend all sorts of disbelief when a setting is intriguing, the plot is good, and the characters are relatable. And they are.

Outside the Norm: Salman Rushdie’s The Enchantress of Florence

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

When I thought about authors whom I might read for this blog, Salman Rushdie never came to my mind. The Enchantress of Florence has been on my to-read stack for a while and I vowed to read it this year, but I never thought that I’d write about it here. A few things occurred in a wonderfully serendipitous way that led me to write this blog. First, my blog about Margaret Atwood’s novels produced an interesting discussion about the label “science fiction” and started me thinking about what that label means.

When I thought about authors whom I might read for this blog, Salman Rushdie never came to my mind. The Enchantress of Florence has been on my to-read stack for a while and I vowed to read it this year, but I never thought that I’d write about it here. A few things occurred in a wonderfully serendipitous way that led me to write this blog. First, my blog about Margaret Atwood’s novels produced an interesting discussion about the label “science fiction” and started me thinking about what that label means.

Second, I recently read an anecdote from Brian Aldiss in which he recounts that he, Arthur C. Clarke, and Kingsley Amis were on a panel to give an award for best science fiction novel. These prestigious panelists chose Salman Rushdie’s first novel Grimus as the winner, but the publisher pulled the book at the last minute because they did not want Rushdie to be pigeonholed as a science fiction writer. Aldiss discusses this in an article, “Why Don’t We Love Science Fiction,” by Bryan Appleyard in The London Sunday Times (Dec. 2, 2007). Aldiss supports the publisher’s actions, saying that if Rushdie had “been labeled a science-fiction writer… nobody would have heard of him again.” I’m not sure that I agree that Rushdie would have been doomed to obscurity, but I keep running across the fact that science fiction writing is not bad writing, but the label is a bad label. Aldiss goes on to discuss the fact that the British embrace fantasy novels as books written for children that it’s okay for adults to read (ex. Tolkien, Pullman, Pratchett, Rowling), while they see science fiction as “adolescent” in the pejorative sense.

This claim, finally, leads me back to The Enchantress of Florence: it is fantasy, but fantasy written for adults. So, what do we do with it? Call it magic realism to legitimize it? We could, but this novel is different from Rushdie’s other novels that I’ve read and do consider to be magic realism. My main argument against the magic realism category is The Enchantress of Florence contains no hint of a modern setting. From the beginning, it immerses the reader in a world that is a magical past and stays there. Do I think that it belongs on the F&SF shelves on my local bookstore? Maybe, maybe not, but I do think that it is the kind of book that many WWEnders would enjoy but might not immediately pick up. (Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, his only book in the WWE database, shows only eleven readers.)

Like many of Rushdie’s works, The Enchantress of Florence juxtaposes East and West. Its historical settings are the court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar the Great and the Renaissance Florence of the de Medicis and Machiavelli. These two settings are linked by the arrival of a blond stranger in Akbar’s city of Fatehpur Sikri. This stranger is a Florentine, pretending to be Queen Elizabeth’s ambassador. (How this comes about makes an interesting start to the novel.) Once that disguise is exposed the stranger begins calling himself by the alias the Mogor dell’Amore (the Mughal of Love). Through this persona, he gains access to Akbar. He says that he has come to tell Akbar a story: “All men needed to hear their stories told. He was a man, but if he died without telling the story he would be something less than that, an albino cockroach, a louse” (89). This story concerns Akbar’s great aunt, the sister of his grandfather. Her name was Qara Köz, and she had been erased from Mughal history. As a young girl, she was a pawn in her brother’s political chess game. She and her sister were given as hostages to the enemy. When she made the choice to remain with her captor, rather than returning to her brother’s court with her sister, her brother, Babar, begins a campaign to erase all traces of her from her native culture.

While unknown in her homeland because of this, she becomes famous in other parts of the world because of her beauty. That beauty evokes power over all men who come in contact with her. Her maid servant, known as the Mirror, is only slightly less beautiful than she is. Here is the experience of one admirer:

“the women coming down toward him were more beautiful than beauty itself, so beautiful that they redefined the term, and banished what men had previously thought beautiful into the ranks of dull ordinariness. A fragrance preceded them down the stairs and wrapped itself around his heart.” (258)

Her beauty is her magic, which she uses to make her way through the world from India to Persia to Anatolia to Florence to the New World, always under the protection of powerful men.

The Mogor dell Amore’s recounting of Qara Köz’s story resembles the tale of The Thousand and One Nights. He portions out his story with digressions and necessary back stories to Akbar, and as he does so, he becomes more and more valuable to the emperor. He is not Scheherazade, telling stories to save his life. Instead he tells the story to find his own place in the world; he is a wanderer looking for a home and implicit in the story he tells is the message that the Mughal empire is his home. However, Rushdie does not model the format of the novel on The Thousand and One Nights. It is not a frame story that focuses on each part of the story as a separate story. Instead, Mogor dell Amore’s story is woven into the narrative of Akbar’s world, which is peopled with trusted advisors, rebellious sons, and multiple wives.

One of these wives, Jodha is particularly interesting, as she sets one of the novel’s themes, man’s search for the “perfect” woman. Jodha is Akbar’s “imaginary wife, dreamed up by Akbar in the way that lonely children dream up imaginary friends, and in spite of the presence of many living, if floating, consorts, the emperor was of the opinion that it was the real queens who were the phantoms and the nonexistent beloved who was real” (27). His other wives, of course, are jealous of Akbar’s phantom favorite, especially since they claim that he built her “by stealing bits of them all” (45). The only woman he wants is a woman who is not. In her well-considered review of the book, Ursula K. Le Guin points out that all the women in the book are “all stock figures, females perceived solely in relation to the male.” While Le Guin is absolutely correct, women’s power in the book comes through the stereotyped arenas of sex or magic; the men are not any better developed and fall into typical roles of mercenary, trickster, king, despot, etc. I believe that this is because Rushdie is trying to tell a fairy story about history and fable and the fine line between them. The Florentine mercenary, Antonino Argalia, is one of my favorite characters. He becomes a Janissary, fighting for Islam’s most powerful leaders and gains so much power that he can command his own mobile community. Among his loyal followers are gigantic Swiss albino brothers–Otho, Botho, Clotho, and D’Artagnan.

One of these wives, Jodha is particularly interesting, as she sets one of the novel’s themes, man’s search for the “perfect” woman. Jodha is Akbar’s “imaginary wife, dreamed up by Akbar in the way that lonely children dream up imaginary friends, and in spite of the presence of many living, if floating, consorts, the emperor was of the opinion that it was the real queens who were the phantoms and the nonexistent beloved who was real” (27). His other wives, of course, are jealous of Akbar’s phantom favorite, especially since they claim that he built her “by stealing bits of them all” (45). The only woman he wants is a woman who is not. In her well-considered review of the book, Ursula K. Le Guin points out that all the women in the book are “all stock figures, females perceived solely in relation to the male.” While Le Guin is absolutely correct, women’s power in the book comes through the stereotyped arenas of sex or magic; the men are not any better developed and fall into typical roles of mercenary, trickster, king, despot, etc. I believe that this is because Rushdie is trying to tell a fairy story about history and fable and the fine line between them. The Florentine mercenary, Antonino Argalia, is one of my favorite characters. He becomes a Janissary, fighting for Islam’s most powerful leaders and gains so much power that he can command his own mobile community. Among his loyal followers are gigantic Swiss albino brothers–Otho, Botho, Clotho, and D’Artagnan.

These names and other little gems demonstrate Rushdie’s humor and style. The sentences are lush and inventive, all the while giving the reader a knowing wink. An example of this occurs when Rushdie describes the ways that the Mogor dell Amore’s story of Qara Köz filters through the citizens of Akbar’s city:

“As the story of the hidden princess began to spread through the noble villas and common gullies of Sikri a languid delirium seized hold of the capital. People began to dream about her all the time, women as well as men, courtiers as well as guttersnipes, sadhus as well as whores…. She even bewitched the queen mother Hamida Bano, who ordinarily had no time for dreams. However, the Qara Köz who visited Hamida Bano’s sleeping hours was a paragon of Muslim devotion and conservative behavior. No alien knight was allowed to sully her purity.” (197)

The Qara Köz who visits Hamida Bano’s sister-in-law, Old Princess Gulbadan, in her dreams, is quite different:

“a free-spirited adventuress whose irreverent, even blasphemous gaiety was a little shocking but entirely delightful… Princess Gulbadan would have envied her if she could, but she was having too much fun living vicariously through her several nights a week.” (197)

If you enjoyed these sentences, you will enjoy The Enchantress of Florence. If you didn’t, you won’t. It’s that simple.

Outside the Norm: Ursula K. Le Guin’s Rocannon’s World and City of Illusions

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

When Rocannon’s World, Planet of Exile and City of Illusions were reprinted in the mid-1970s, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote introductions for each novel. Those introductions contain two passages that tell you everything that you need to know about Rocannon’s World and City of Illusions:

When Rocannon’s World, Planet of Exile and City of Illusions were reprinted in the mid-1970s, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote introductions for each novel. Those introductions contain two passages that tell you everything that you need to know about Rocannon’s World and City of Illusions:

Most of my stories are excuses for a journey. (We shall henceforth respectfully refer to this as the Quest Theme.) I never did care much about plots, all I want is to go from A to B—or, more often, from A to A—by the most difficult and circuitous route. (“Introduction to City of Illusions” in The Language of the Night 147)

And:

But of course fantasy and science fiction are different, just as red and blue are different; they have different frequencies; if you mix them (on paper—I work on paper) you get purple, something else again. Rocannon’s World is definitely purple. (“Introduction to Rocannon’s World” in The Language of the Night 133)

Both novels are about planetary outsiders who must go on a quest. Rocannon, the ethnologist studying Fomalhaut II, is the sole survivor of his expedition group. An unknown alien race blows up his ship and his companions. The destruction of the ship eliminates his mode of communication; therefore, he can’t tell his people that the planet has been attacked. He has no way to protect the indigenous people. Traveling south to the base of the enemy to use their communication equipment to contact his people is his only option. Rocannon assembles a Tolkiensque group, and they begin their quest. The beats of their journey closely resemble Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, outlined in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. There are helpers, threshold guardians, tests, and even a bit of apotheosis. (Another good website about the monomyth is here.)

Falk’s journey in City of Illusions is a quest to learn who he is. The novel opens with Falk’s discovery by an agrarian society. He has no memory, no language. They foster him and teach him their ways, but he is not of their species. He has amber, cat-like eyes that mark him as alien. After living with these people for five years, his instinct tells him that he must journey west toward the legendary city of Es Toch to learn who he is. Unlike Rocannon, he usually travels alone, but like Rocannon, he encounters tests, helpers and threshold guardians along the way.

I enjoyed the “purpleness” of both novels as they placed the quest myth on unknown, or at least immediately unrecognizable, planets, whose cultures would be at home in high fantasy. In Rocannon’s World, Le Guin enlivens Norse myth with a slice of Tolkien. The Liuar species who travel with Rocannon has two classes: the Olgyior, who are the servants, and the Angyar, who are the lords. They live within a “feudal-heroic culture,” which Le Guin sums up this way: “They were a boastful race, the Angyar: vengeful, overweening, obstinate, illiterate, and lacking any first-person forms for the verb ‘to be unable.’ There were no gods in their legends, only heroes” (4, 37).

I enjoyed the “purpleness” of both novels as they placed the quest myth on unknown, or at least immediately unrecognizable, planets, whose cultures would be at home in high fantasy. In Rocannon’s World, Le Guin enlivens Norse myth with a slice of Tolkien. The Liuar species who travel with Rocannon has two classes: the Olgyior, who are the servants, and the Angyar, who are the lords. They live within a “feudal-heroic culture,” which Le Guin sums up this way: “They were a boastful race, the Angyar: vengeful, overweening, obstinate, illiterate, and lacking any first-person forms for the verb ‘to be unable.’ There were no gods in their legends, only heroes” (4, 37).

Also, on the planet are the Gdemiar, who had a dwarfish culture before the Hainish envoys enhanced their culture to an industrial level, and the Fiia, who live an elvish, agrarian lifestyle. The Fian, Kyo, who has lost his whole village, joins the quest, giving the reader an insight into that culture that we don’t with the Gdemiar.

In City of Illusions Falk’s journey across a post-apocalyptic North American continent exposes him to many cultures we would see in fantasy novels. There are extended-family agrarians, hunter-gatherers, Taoist hermits, and isolationists, all of whom have developed rituals that suit their cultural needs. The isolationists are the Bee-Keepers, “[a] strange lot, literate and laser armed, all clothed alike, men and women, in long shifts of yellow wintercloth marked with a brown cross on the breast” (277).  While they treat Falk well, he learns that they capture outside women solely to breed more Bee-Keepers and “worship something called the Dead God, and placate him with sacrifice—murder” (278). Each group Falk encounters serves as either helpers or hinderers on his journey, just as they should in a good quest myth.

While they treat Falk well, he learns that they capture outside women solely to breed more Bee-Keepers and “worship something called the Dead God, and placate him with sacrifice—murder” (278). Each group Falk encounters serves as either helpers or hinderers on his journey, just as they should in a good quest myth.

The characters and ideas expressed in City of Illusions are much more complex than those in Rocannon’s World. Le Guin’s Taoism is much more pronounced as she queries the difference between truth and lies throughout Falk’s journey. The characters and situations are much more gray than the starker black and white of Rocannon’s World. However, I enjoyed reading Rocannon’s World much more. I liked Rocannon more than Falk, perhaps because Falk is a mystery through most of the book. Both books give us a glimpse of the writer that Le Guin will become. We see her world-building, her fascinating cultures, and her wonderful prose.

Outside the Norm: Ursula K. Le Guin’s Planet of Exile

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

My last blog about Margaret Atwood and science fiction inadvertently led me back to Ursula K. Le Guin, who has been an important commentator on Atwood’s work. (See the comments to that blog to find some interesting links to Le Guin about Atwood and Atwood about Atwood.)

My last blog about Margaret Atwood and science fiction inadvertently led me back to Ursula K. Le Guin, who has been an important commentator on Atwood’s work. (See the comments to that blog to find some interesting links to Le Guin about Atwood and Atwood about Atwood.)

An omnibus edition of Le Guin’s works called Three Hainish Novels has been moving in and out of my to-be-read stack for more years than I’d like to admit. This edition contains the first three Hainish novels, Rocannon’s World (1966), Planet of Exile (1966), and City of Illusions (1967). I don’t know why I’ve not read these novels yet. My favorite book is The Left Hand of Darkness. (I know this because a colleague recently made me choose one book for a list he was putting together. It was very hard to choose, so I decided to pick the book that I had re-read more than any other. That was The Left Hand of Darkness.) When I read it in the late 80s, The Left Hand of Darkness changed the way that I thought about gender, writing, and science fiction. It even spurred me to do a research paper in a linguistics class about pronouns and gender. So, now, almost thirty years later, it’s time to finish the Hainish Cycle, beginning with these three novels. This blog will discuss the middle novel, Planet of Exile.

I like Soft SF, and I like world-building novels. And, lucky for me, so does Le Guin. She writes in her essay "Do-It-Yourself Cosmology":

As soon as you, the writer, have said, "The green sun had already set, but the red one was hanging like a bloated salami above the mountains," you had better have a pretty fair idea in your head concerning the type and size of green suns and red suns—especially green ones, which are not the commonest sort—and the arguments concerning the existence of planets in a binary system, and the probable effects of a double primary on orbit, tides, season, and biological rhythms; and then of course the mass of your planet and the nature of its atmosphere will tell you a good deal about the height and shape of those mountains, and so on, and on…. None of this background work may actually get into the story. But if you are ignorant of these multiple implications of your pretty red and green suns, you’ll make ugly errors, which every fourteen-year-old reading your story will wince at; and if you’re bored by the labor of figuring them out then surely you shouldn’t be writing science fiction. (The Language of the Night, 122)

This kind of specificity and willingness to play with the implications of physical systems allow Le Guin to create intriguing societies that relate to the attributes of the planet. For example, the properties of Werel, featured in Planet of Exile, will create very resilient cultures that are governed by seasonal rhythms:

The green third planet took sixty of Earth’s year’s to complete it year…. The winters of the northern hemisphere, tilted by the angle of the ecliptic away from the sun, were cold, dark, terrible: the vast summers, half a lifetime long, were measurelessly opulent. Giant tides of the planet’s deep seas obeyed a giant moon that took four hundred days to wax and wane. (City of Illusions 307)

Planet of Exile opens as this long, bitter winter comes, and one of the indigenous populations, the Tevarans, begins building its Winter City, a place where this agrarian culture will hunker down to outlast the raging winter and the raids of the nomadic culture, the Gaals, who always move south in winter. This hibernation of approximately fifteen Earth years is something the culture dreads and works to provide for throughout the rest of the long Werel year.

The fertility of the Tevarans is governed by the rhythm of the seasons. One is either Autumn-born or Spring-born. Rolery, a child born in the Summer, is out of sync with her people. Her Father, Wold, considers her place in this polygamous culture:

She looked to be about twenty moonphases old, which meant she was the one born out of season, right in the middle of the Summer Fallow when children were not born. The sons of Spring would by now be twice or three times her age, married, remarried, prolific; the Fall-born were all children yet. But some Spring-born fellow would take her for third or fourth wife; there was no need for her to complain. (Planet of Exile 150)

However, Rolery explains her situation differently:

[W]hen Winter’s over I’ll be too old to bear a Spring child. I’ll never have a son. Some old man will take me for a fifth wife one of these days, but the Winter Fallow has begun, and come Spring I’ll be old…. So I will die barren. It’s better for a woman not to be born at all than to be born out of season as I was. (Planet of Exile 150)

Rolery’s situation makes her an outsider in her own culture. She does not have an age cohort. Her loneliness fuels her curiosity about the other cultures that inhabit the planet. The book opens with Rolery brazenly entering the city of the farborns, the Alterran colonists who arrived six hundred years earlier and had lost contact with their empire, the League of All Worlds. Rolery wants to see the sea, so she travels through the Alterran city. She is almost caught by the fast moving tide, but is saved when the Alterran, Jakob Agat "bespeaks" her—he sends her a telepathic message to run.

This encounter begins a relationship between Rolery and Jakob. Her situation as a Summer-born allows her to pursue this semi-taboo relationship. (Her father once had a farborn wife, but, of course, Wold is the tribe leader and a man.) Sexual relationships between Alterrans and the planet’s indigenous populations are sterile, but Rolery knows that she is doomed to barren relationships. Therefore, she chooses to become the first wife in a monogamous marriage rather than a later wife in a polygamous marriage.

This encounter begins a relationship between Rolery and Jakob. Her situation as a Summer-born allows her to pursue this semi-taboo relationship. (Her father once had a farborn wife, but, of course, Wold is the tribe leader and a man.) Sexual relationships between Alterrans and the planet’s indigenous populations are sterile, but Rolery knows that she is doomed to barren relationships. Therefore, she chooses to become the first wife in a monogamous marriage rather than a later wife in a polygamous marriage.

This "star-crossed lovers" plot is only a sub-plot in the novel. The real marriage happens between the Alterrans and the Tevarans, who must learn to rely on one another. Those pesky Gaals, who in the past had briefly harried the Winter Cities and the Alterran city as each nomadic group journeyed southward, have organized. Under the leadership of a Gaal Ghengis Khan, these hordes are moving southward as a conquering machine, burning cities, and stealing livestock and provisions. They leave death and destruction behind. Alterran scouts report this to Jakob, who must convince Wold and the Tevarans of the danger. His relationship with Rolery damages his credibility, and as a result of the Tevaran’s inaction their Winter City is destroyed by the Gaal. Alterran guerillas are able to save many of the Tevarans and bring them into their city. The long siege begins, and the Alterrans and the Tevarans have to learn how to live together.

The book is a fun and quick read. The romance is not overdone, and the cultures that Le Guin creates are developed and are not simply opposites of each other. Each culture demonstrates some interesting nuances that fit their unique situations. I think this novel is my favorite of the three. More on the other two in my next blog.

Outside the Norm: Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin and Oryx and Crake

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

Margaret Atwood has famously denied that she writes “science fiction,” claiming instead that she writes “speculative fiction,” a claim that always sounds less condescending coming from Harlan Ellison than it does from Atwood. This is probably because Ellison knows what he’s trying to define, and Atwood is trying to craft a definition that excludes her own writing from science fiction. According to Atwood, science fiction “is when you have chemicals and rockets” or “monsters and spaceships” or “talking squids in outer space.” For analyses of Atwood’s definitions, see Peter Watts, “Margaret Atwood and the Hierarchy of Contempt” and David Langford, “Bits and Pieces.”

Margaret Atwood has famously denied that she writes “science fiction,” claiming instead that she writes “speculative fiction,” a claim that always sounds less condescending coming from Harlan Ellison than it does from Atwood. This is probably because Ellison knows what he’s trying to define, and Atwood is trying to craft a definition that excludes her own writing from science fiction. According to Atwood, science fiction “is when you have chemicals and rockets” or “monsters and spaceships” or “talking squids in outer space.” For analyses of Atwood’s definitions, see Peter Watts, “Margaret Atwood and the Hierarchy of Contempt” and David Langford, “Bits and Pieces.”

My recent reading of two Atwood novels shows me that she can write science fiction badly and that she can write science fiction well. To be fair, I believe that she was trying to write bad science fiction in The Blind Assassin (2000). This winner of the Booker Prize is a multi-layered novel in which octogenarian Iris Chase Griffen recounts the life of her sister Laura Chase, the author of The Blind Assassin. This fictional book-within-a-book was published after Laura’s untimely death and gained a cult following. The sections of Atwood’s book alternate between Iris writing the story of the Chase girls’ youth and Laura’s novel. The plot of this internal novel is simple: in the 1930s and 40s a married upper-class woman has a clandestine affair with a lower-class man who is on the run. Both these characters are unnamed. He is most likely an active communist who is being pursued by the authorities. He makes his living by writing for science fiction pulp magazines. Most of these chapters follow the formula of the woman visiting the man at his current hideout where their post-coital pillow talk consists of the man entertaining her with science fiction stories he makes up on the spot. Their first foray into storytelling begins like this:

What will it be, then? he says. Dinner jackets and romance, or shipwrecks on a barren coast? You have your pick: jungles, tropical islands, mountains. Or another dimension of space—that’s what I’m best at.

Another dimension of space? Oh really!

Don’t scoff, it’s a useful address. Anything you like can happen there. Spaceships and skin-tight uniforms, ray guns, Martians with the bodies of giant squids, that sort of thing. (9)

It is significant that the character’s list mirrors the entities that Atwood herself references in interviews as I have shown above. Clearly, Atwood, as the writer of The Blind Assassin, and the male writer have a very low opinion of science fiction and its abilities to develop character or plot. For him, science fiction is about an Other (completely undeveloped) and cheap thrills, as their negotiations show:

Then you could have a pack of nude women who’ve been dead for three thousand years, with lithe, curvaceous figures, ruby-red lips, azure hair in a foam of tumbled curls, and eyes like snake-filled pits. But I don’t think I could fob those off on you. Lurid isn’t your style.

You never know I might like them.

I doubt it. They’re for the huddled masses. Popular on the covers though—they’ll writhe all over a fellow, they have to be beaten off with rifle butts.

Could I have another dimension of space, and also the tombs and the dead women, please?

That’s a tall order, but I’ll see with I can do. I could throw in some sacrificial virgins as well, with metal breastplates, and silver ankle chains and diaphanous vestments. And a pack of ravening wolves, extra. (9)

This negotiation ends with him beginning his story of the planet Zycron, which contains some of the ideas he discusses above. The story has too many plot details, many of them never expanded nor explored. While not all of his story ideas are completely cliché in execution, these two pieces of dialog demonstrate how Atwood pigeonholes science fiction.

Unfortunately for Atwood, the story of the lovers and their pulp pursuits are much more interesting than Iris’ main narrative which grows tedious after a while. Also, I figured out the ending surprises with more than 200 pages left which did not increase my interest in the stories Iris tells in either the past or the present. Also, I had trouble reconciling the characters of Iris in the past with Iris in the present.

Oryx and Crake (2003) shows that Atwood can write good science fiction; however, she would call it speculative fiction, or writing “based on rigorously-researched science, extrapolating real technological and social trends into the future” (Watts 2). And I thought that was what science fiction was. Atwood creates an interesting post-apocalyptic world in which there is one human survivor who calls himself Snowman. Snowman is the caretaker of a race of bio-engineered humanoids, who were created by his friend Crake. According to Crake, all aggression, greed, and competition have been eliminated in this race. They have an advanced life cycle, becoming “adults” after only a few years. They live a pre-lapsarian lifestyle and eat roots, fruits, and grass. Snowman serves as kind of prophet for them. He teaches them about the flotsam they discover from the previous civilization, telling them if it is useful or dangerous.

Oryx and Crake (2003) shows that Atwood can write good science fiction; however, she would call it speculative fiction, or writing “based on rigorously-researched science, extrapolating real technological and social trends into the future” (Watts 2). And I thought that was what science fiction was. Atwood creates an interesting post-apocalyptic world in which there is one human survivor who calls himself Snowman. Snowman is the caretaker of a race of bio-engineered humanoids, who were created by his friend Crake. According to Crake, all aggression, greed, and competition have been eliminated in this race. They have an advanced life cycle, becoming “adults” after only a few years. They live a pre-lapsarian lifestyle and eat roots, fruits, and grass. Snowman serves as kind of prophet for them. He teaches them about the flotsam they discover from the previous civilization, telling them if it is useful or dangerous.

Before he became the prophet of the Crakers (as he calls them), Snowman was Jimmy, who grew up in an enclosed corporate compound called OrganInc Farms. His father was a prominent bio-engineer working on the Pigoon Project, which created pigs that would grow “an assortment of foolproof human-tissue organs” for transplanting into humans (22). These compounds were mostly self-contained with malls, schools, hospitals, etc. that served the needs of the employees and their families. The compounds are connected by tube trains. The areas in between are called pleebland (read pleeb-land), where the mass of humanity lives: economically disadvantaged, diseased, and the ultimate consumers for the products and techniques created in the compounds. This sociological layout reminds me very much of the world Marge Piercy creates in He, She and It, except that Piercy’s economy is based on computer technology and virtual reality instead of bio-engineering.

Snowman’s narrative covers just a few days in his present as he tries to survive in this devastated landscape where food is scarce and new predators, which were former science projects housed in labs, roam. There are snats (a cross between snakes and rats) and wolvogs (a cross between a dog and a wolf). Also, the pigoons have become carnivores and are getting smarter. The bulk of the past story is about Jimmy, how he came to be a survivor, his love for Oryx, and his friend Crake’s ambition to create better human beings. The end of the book finally shows the readers how the rest of humanity met its demise and the roles that Jimmy, Oryx and Crake played in that disaster.

This book was very enjoyable. The science seems science-y enough, and her portrayal of “reality” broadcasts over the internet, where one could find the Noodie News, open heart surgeries, live coverage of executions, and, of course, enough pornography to cover any viewer’s choices or fetishes, seems especially prescient. The plot is well-paced, and both the present and past events are interesting, so I never found myself wishing I could move on to the next time period, like I did with The Blind Assassin. While I cannot say that I liked The Blind Assassin as much as I liked Oryx and Crake, Atwood writes beautifully and is a pleasure to read. I plan to read The Year of the Flood and The Handmaid’s Talec later this year for this blog.

Full Details

Full Details