GMRC Review: Deathbird Stories by Harlan Ellison

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the fourth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the fourth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

If there ever was a kind of excessive, unorthodox or hysterical posturing in SF, Harlan Ellison definitely embodies it. And not only in the choice of the titles of his impressive stories. He certainly has a flare for verbal thrift, rarely struggling to grope for effect, as Connie Willis may well atest to. Despite his outrageous actions that often include letigation of all kinds against an impressive cast of you-know-who’s, which I believe has a lot more to do with upholding a bad-boy image than anything else of substance, Ellison certainly is gifted with literary cleverness and as such is one of the most decorated writers in the genre, winning over 100 awards. He works almost exclusively within the short story form, and consequently has remained little known outside SF circles. Apart from editing the landmark Dangerous Visions anthology, and its follow-up Again, Dangerous Visions, Ellison also did some work on Star Trek, Babylon 5 and The Outer Limits, one episode of which named "Soldier" being the inspiration for The Terminator. True to form, Ellison sued.

If there ever was a kind of excessive, unorthodox or hysterical posturing in SF, Harlan Ellison definitely embodies it. And not only in the choice of the titles of his impressive stories. He certainly has a flare for verbal thrift, rarely struggling to grope for effect, as Connie Willis may well atest to. Despite his outrageous actions that often include letigation of all kinds against an impressive cast of you-know-who’s, which I believe has a lot more to do with upholding a bad-boy image than anything else of substance, Ellison certainly is gifted with literary cleverness and as such is one of the most decorated writers in the genre, winning over 100 awards. He works almost exclusively within the short story form, and consequently has remained little known outside SF circles. Apart from editing the landmark Dangerous Visions anthology, and its follow-up Again, Dangerous Visions, Ellison also did some work on Star Trek, Babylon 5 and The Outer Limits, one episode of which named "Soldier" being the inspiration for The Terminator. True to form, Ellison sued.

His best known collection is arguably The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World, which features the definitive New Wave story "A Boy And His Dog" that won the Nebula for best novella, and upsetting almost everyone, from liberals and feminists to the right wing alike, and of course, many of the Golden Age SF writers. After having read a few of Ellison’s stories, "A Boy and His Dog" remains his best, one of the few post-apocalyptic narratives to depict how raw and brutal existence after a nuclear holocaust would be – and equally successful in protesting and allegorizing the Vietnam War. Equally ingenious is Deathbird Stories, a collection probably closest to the horror genre, with an odd few elements of science fiction and fantasy thrown in.

As the subtitle, A Pantheon of Modern Gods, suggests, the theme is gods, and in particular the "new" gods (or devils) of our modern society. These are: the god of speed, the god of beauty, the god of money, the god of mechanical and technoligcal wonders, the god of apocryphal dreams and the gods of pollution. Even the god of the guilty, if there could be such a thing, albeit a Freudian trope. The stories are tied together by the concept that gods are real only as long as they have people who believe in them. We find echoes of this in Neil Gaiman’s phenominal American Gods. Ellison writes in the introduction:

"When belief in a god dies, the god dies… to be replaced by newer, more relevant gods."

It’s not a far-fetched assumption. Afterall, Thor and Odin disappeared when the Vikings took up the cross and Apollo was reduced to rubble along with his temples. Ellison offers a litany of dead gods. These 19 stories are essentially about the merits of religion and the religious and true to form, Ellison crushes eggshells in his usual confrontational manner, with a caveat lector at the beginning that warns the reader against reading the entire collection in one sitting because of the "emotional content:"

"It is suggested that the reader not attempt to read this book at one sitting. The emotional content of these stories, taken without break, may be extremely upsetting. This note is intended most sincerely, and not as hyperbole."

Despite there being an element of humor in some of these stories, the warning should not be taken lightly. It is not the usual Ellison arrogance at play here – they did exhaust and deaden my spirit. Still, Ellison’s missive does drive home the point that mankind is drifitng away from the belief in a benevolent, all-knowing, all-loving God and is instead transferring its faith to soulless pursuits and material possessions. There are truths present here, and some of them are very uncomfortable, taking the shape of monstrous, twisted forms, old creatures of myth like basilisks, gargoyles, minotaurs and even dragons, allegories for the new gods of gambling, the modern metropolis, pollution, sex, automobile showrooms and many other depraving endeavors. The gods appear to be a remarkably fragile lot.

These are my favorite stories from the collection:

"Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes" is about the god of the slot machine and the subsequent dead-end that Las Vegas could be. A similar kind of worship is found in "Neon," about a guy who seeks carnal knowledge with neon lights.

"Along the Scenic Route" is a narrative about a freeway autoduel of the future, very prescient to our modern day road-rage fueled obsessions on the world’s freeways.

"Basilisk" perspicaciously combines the Greek myth of a serpent-like creature with a lethal gaze and Mars, the hungry God of War. Lance Corporal Vernon Lestig does terrible things but I understood, and may even have sympathised with his reasons.

"On the Downhill Side" is just a beautiful and touching story about two ghosts who meet on a street in New Orleans. The God of Love allows them one more chance to find love in each other’s arms. The man had loved too much, leading to multiple divorces and his ultimate suicide, and the woman had remained a virgin until her early death. There is a dire price to be paid, a sacrificial compromise "forming one spirit that would neither love too much, nor too little." I could not help feeling that this is probably how Ellison truly sees love and religion operating. An emotionally engaging story, perfectly paced – I simply loved it.

"Shattered Like a Glass Goblin" invokes the paranoid fears brought about by hallucinogenic drugs within the surreal atmosphere of a hippie retreat. I find this story a magnificent allegory on the all-consuming downward spiral of drug addiction, culminating in a final hallucination as deciphered symbol of the inevitable surrender of the main protagonist, who thinks he is a glass sculpture of a goblin and his girlfriend a werewolf. When he tries to talk to her for one final time, she attacks him and he shatters into a thousand pieces.

"Paingod," which is my clear favorite in the entire collection, is about Trente the Paingod, who delivers pain and suffering when and if necessary to each conscious being across all the universes, and decided one day to find out first-hand what pain feels like from a sculptor who has lost his ability to sculp. The harrowing conclusion that pain is a blessing because without it there can be no joy still reverberates strongly with me.

The three weakest stories for me are:

"Rock God" is a rather pedestrian affair, dated, with the frantic corruptness of the protagonist very stereotypical.

"At the Mouse Circus" which I can’t say anything meaningful except that it features the king of Tibet and a cadillac and that I have no idea what Ellison is trying to convey.

"The Place With No Name" has Prometheus in it, but much like the movie, disappoints with things I did not understand at all and other things that were only too clear. There is this somewhat shocking denouement: what if Jesus and Prometheus had been lovers, were aliens that felt strong and loving empathy toward earthlings and gave them gifts, only to be punished (and crucified) by the other gods for doing so?

A polarizing collection with this many narratives dealing more or less with the same subject matter is bound to have a few unappealing stories. Nonetheless, there are still other, brilliant and well crafted stories like the catchy "Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans: Lattitude 38° 54′ N, Longitude 77° 00′ 13" W" and the story the title is taken from, "Deathbird." I’m certain everyone who reads this collection will discover their own favorites. Take note of the caveat lector, though and read these divergent stories cautiously over a stretched period of time. They are hugely rewarding, even if exhausting. Ellision has always been a polemic figure who has never been afraid to articulate and share his opinions. This is true even of his writing. It is a difficult read, even painful at times, but as Ellison so expressly pointed out: what is joy without a little pain?

A polarizing collection with this many narratives dealing more or less with the same subject matter is bound to have a few unappealing stories. Nonetheless, there are still other, brilliant and well crafted stories like the catchy "Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans: Lattitude 38° 54′ N, Longitude 77° 00′ 13" W" and the story the title is taken from, "Deathbird." I’m certain everyone who reads this collection will discover their own favorites. Take note of the caveat lector, though and read these divergent stories cautiously over a stretched period of time. They are hugely rewarding, even if exhausting. Ellision has always been a polemic figure who has never been afraid to articulate and share his opinions. This is true even of his writing. It is a difficult read, even painful at times, but as Ellison so expressly pointed out: what is joy without a little pain?

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

New WWEnd member Grace (BookWithoutPics) is a bibliophile and aspiring librarian who reads a lot of books. She reviews SF/F and other books on her excellent blog Books Without Any Pictures where this review originally appeared. She has shared it with us in honor of Juneteenth.

If I had to sum up the book in one phrase, I’d say that this book is Murphy’s law applied to time travel. Everything that can go wrong does, and at the worst possible time.

If I had to sum up the book in one phrase, I’d say that this book is Murphy’s law applied to time travel. Everything that can go wrong does, and at the worst possible time.

Kindred is technically classified as sci-fi, but it is a genre-bending novel that also incorporates elements of historical fiction. It tells the story of Dana, a modern black woman from California who is pulled back in time to the early 1800s in Maryland to rescue her distant white ancestor Rufus when his life is endangered. Dana makes six visits to the past during the course of the novel and is only able to return home when she believes that her own life is threatened.

Dana is forced to confront the horrors of slavery as she spends time in the past and struggles with her own identity as she is swept into life on the plantation. Meanwhile, she finds herself in the rather awkward (and completely f’ed up) position of having to make sure that Rufus has sex with a woman named Alice so that her ancestors would be born and she wouldn’t flicker out of existence a la Back to the Future.

Kindred is such a powerful story because Dana is so easy to identify with. She’s intelligent, resourceful, and a very much a product of modern life. When we see slavery from the eyes of someone from our own world it makes everything seem so much more real than it would in a typical historical fiction novel. We see Dana react to the past in a multitude of different ways, ranging from her initial realization that she wasn’t in 1976 anymore when kid-Rufus used a racial slur against her to the panic at realizing that medicine in the early 1800s could be downright scary (bloodletting? leeches? gross!). It’s extreme culture shock on a multitude of different levels, but Dana eventually finds herself adapting and learning to understand the mindset of surviving the violence and dehumanization that her ancestors faced.

One of the things that I also enjoyed about this book was seeing Dana’s relationship with her husband Kevin. She and Kevin are both writers and are very clearly soulmates. We see some of her backstory with Kevin, including the way that both of their families handled the fact that they were an interracial couple (badly, of course). However, the problems that Dana and Kevin face in the modern world pale in comparison to the harsh reality of life in the 1800s.

One of the things that I also enjoyed about this book was seeing Dana’s relationship with her husband Kevin. She and Kevin are both writers and are very clearly soulmates. We see some of her backstory with Kevin, including the way that both of their families handled the fact that they were an interracial couple (badly, of course). However, the problems that Dana and Kevin face in the modern world pale in comparison to the harsh reality of life in the 1800s.

Dana discovers that anything she’s carrying when she gets pulled into the past goes with her, so she packs herself a bag and on one occasion even takes her husband with her. Kevin tries to use his social standing to protect her, but that doesn’t make Dana’s experience of the past any less dangerous.

I read Kindred in one sitting and was on the edge of my seat the entire time. Octavia Butler‘s writing is articulate and powerful, and she is able to make readers not just see the past but also feel it. Kindred is one of the best books that I’ve ever read, and I’d highly recommend it.

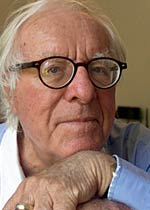

GMRC Review: The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury

Daniel Roy (triseult), has contributed over 30 reviews to WWEnd including this, his second, for the GMRC. Daniel is living his dream of travelling the world and you can read about some of his adventures on his blog Mango Blue.

Daniel Roy (triseult), has contributed over 30 reviews to WWEnd including this, his second, for the GMRC. Daniel is living his dream of travelling the world and you can read about some of his adventures on his blog Mango Blue.

There are SF books that age superbly well, staying relevant and believable decades beyond their publication dates. The Martian Chronicles is not such a book; it’s a delicate antique, the fossilized remains of dreams and terrors gone by, of a time when Mars had water irrigation canals, and everyone feared death by atomic war. It may not have remained relevant, but its lyrical beauty is intact.

Martian Chronicles is a series of loosely connected short stories set on the planet Mars; more specifically, on the planet Mars as it existed in the collective consciousness of the 1950s, when the lines slashed across its surface were water canals built by an ancient and alien civilization. In 2012, it reads not so much as science fiction, but as a form of dreamy fantasy, an alternate universe where the science fiction dreams of the Martian wild frontier are true. This gives a charming air of naïveté to the stories, a nostalgia of dreams gone by, made impossible by the images sent back by Viking and Pathfinder.

There exists a quaint notion in the public’s mind that a SF author’s greatness can be measured by his or her power to predict the future: much attention is given to Isaac Asimov anticipating the Laws of Robotics, or of Arthur C. Clarke having predicted orbital satellites. But reading The Martian Chronicles, it’s obvious that great SF writers do not so much try to anticipate and predict the future, but rather dream of all possible futures.

That’s what the stories in The Martian Chronicles feel like; a dream. They possess a dreamy, ethereal quality, the descriptions filled with a deep sense of wonder and joy at the Universe, a lyricism and poetry that depart in a formidable fashion from the dry intellectualism of Bradbury‘s contemporaries at the time. The stories themselves are enchanting, sometimes gripping; they never grow grim, even if they deal with death, yearning, sometimes murder, sometimes outright war. Some of the stories present arresting imagery to this day: the sight of all African Americans, having given up on ever being granted full civil rights, gathering their belongings and leaving for Mars; or the clockwork rhythms of an automated house, calling the children to breakfast long after Earth has died in an atomic war.

My biggest gripe with Martian Chronicles is the fate of the Martians themselves, and the relative lack of empathy given to what Bradbury imagined as beautiful, wise creatures. Their fate mirrors that of Native Americans, and perhaps because the novel was of its time, their destruction under the relentless wheels of colonization did not stir much sympathy in Mr. Bradbury. There was a huge opportunity to discuss the human/Martian cost of the American spirit of endeavor, but this is a theme which Mr. Bradbury has preferred should remain untouched.

My biggest gripe with Martian Chronicles is the fate of the Martians themselves, and the relative lack of empathy given to what Bradbury imagined as beautiful, wise creatures. Their fate mirrors that of Native Americans, and perhaps because the novel was of its time, their destruction under the relentless wheels of colonization did not stir much sympathy in Mr. Bradbury. There was a huge opportunity to discuss the human/Martian cost of the American spirit of endeavor, but this is a theme which Mr. Bradbury has preferred should remain untouched.

On a personal note, I began reading The Martian Chronicles on June 5th, 2012, unaware that Mr. Bradbury had passed away on that very day. By a strange twist of fate, despite having grown up with SF stories, I had never read any book by Mr. Bradbury before. I’m glad I finally, if a bit too late, learned to appreciate the greatness of his writings, and why so many authors consider him an inspiration.

When Mr. Bradbury passed away, Humanity has lost a dreamer. But judging by the beauty and grace of this book, the dreamer’s dreams live on.

Outside the Norm: Karen Lord’s Redemption in Indigo

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

Nalo Hopkinson calls Karen Lord‘s Redemption in Indigo "[t]he impish love child of Tutuola and Garcia Marquez." I have never read Tutuola, but I immediately understood Hopkinson’s comment when I started reading the book and thought it was a mixture of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. So, no matter what authors or book the readers use for their analogies, the most compelling feature of Redemption in Indigo is its ability to mix New World magical realism with Old African folktales, in her case the world of Barbados and its undying spirits, the djombi, with the Senegalese folktales of Anansi, the spider trickster god.

Nalo Hopkinson calls Karen Lord‘s Redemption in Indigo "[t]he impish love child of Tutuola and Garcia Marquez." I have never read Tutuola, but I immediately understood Hopkinson’s comment when I started reading the book and thought it was a mixture of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. So, no matter what authors or book the readers use for their analogies, the most compelling feature of Redemption in Indigo is its ability to mix New World magical realism with Old African folktales, in her case the world of Barbados and its undying spirits, the djombi, with the Senegalese folktales of Anansi, the spider trickster god.

The book begins by setting up the narrative as a tale told by a storyteller: an "I" who is talking to a group of "yous," of which the reader is one. The story playfully ends with the storyteller’s solicitations:

"it is terribly dry and thirsty work, speaking these lives into the dusty air of the court, speaking for you to hear and ponder and judge. Perhaps, if you would be so kind as to contribute, I could purchase some refreshments now, find a place to rest my head later, and return to you on the morrow with my voice and memory and strength restored. Please, ladies and gentlemen, if you have at all enjoyed my story, be generous as the pot goes around, and do come back again soon." (182)

He similarly begins the epilogue by telling us that he has been "authorised" to tell us more. This narrative method enhances the folktale elements because it provides an inventive way to fill in cultural background for readers who probably aren’t familiar with the ways of the greater and lesser djombi and the other supernatural beings they encounter.

Our storyteller begins with the story of Paama, who’s left her husband, Ansige, and returned with her family to her village. Paama leaves her husband because of his gluttony. He was "not an epicure, but a gourmand," his every thought and action controlled by his desire for food and his only worry about his next meal (7). When Ansige finally arrives at the village to beg her to return to him, his exploits demonstrate his origin in East African folktale characters. His gluttony gets him into all kinds of trouble from which Paama has to rescue him. However, Paama has bigger problems than her husband. Before Ansige even arrives at her village, two djombi have decided to steal Chaos from another djombi and give it to Paama, which will give her immense power. Just as Paama starts to understand her unwanted power, the indigo djombi, the original wielder of Chaos, has tracked his power to her village.

The relationships Lord forges between the supernatural beings and humanity elevate the plot beyond the typical tale of a heroine who must fight to save her people and their way of life. The supernatural beings are complex characters who are dissatisfied with the way their identities often limit their roles. The storyteller speaks about the indigo djombi:

The djombi are like the human creatures they meddle with, apt either to great evil or great good, and sometimes they switch sides.

This one was the unknown danger. He had switched sides. He had started with benevolence, with the belief that there is the fine potential in humankind waiting only to be tapped. He now viewed the whole stinking breed as a pest and a plague. (58)

As a symbol of his change from benevolent to malignant, the djombi changes his color to indigo, "a stark and utter setting apart that provoked as much of horror as of awe" (59). Another supernatural being, the Trickster, who usually appears in the form of a spider, changes in the opposite direction. He began "delighting in the frailties of humans and exploiting those weaknesses for his own entertainment" but became bored with "playing the same old practical jokes" (102). After a while he started "turning people to situations of mutual benefit rather than merely gratifying his own sense of the ridiculous" (102). The pleasure in this novel is observing these beings as they learn about their omnipotence and start to interact with Paama and her community in a meaningful way. The ending, while somewhat predictable, gives the readers the happy endings and the redemptions that the title tells them to expect.

As a symbol of his change from benevolent to malignant, the djombi changes his color to indigo, "a stark and utter setting apart that provoked as much of horror as of awe" (59). Another supernatural being, the Trickster, who usually appears in the form of a spider, changes in the opposite direction. He began "delighting in the frailties of humans and exploiting those weaknesses for his own entertainment" but became bored with "playing the same old practical jokes" (102). After a while he started "turning people to situations of mutual benefit rather than merely gratifying his own sense of the ridiculous" (102). The pleasure in this novel is observing these beings as they learn about their omnipotence and start to interact with Paama and her community in a meaningful way. The ending, while somewhat predictable, gives the readers the happy endings and the redemptions that the title tells them to expect.

Because Karen Lord explores these big ideas of omnipotence and redemption in a Caribbean setting, her book has garnered attention outside the F/SF community. It won the 2008 Frank Collymore Award, given to an unpublished Barbadian work. It was also nominated for the 2011 Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. Back in the F/SF world, the book was a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and won the 2011 Mythopoetic Award and the 2011 Crawford Award for the best fantasy novel by a new writer. For more on its awards, see Karen Lord’s interview with Chesya Burke.

The adjective that comes to mind when I think about Redemption in Indigo is fresh. The story has recognizable elements–heroes, gods meddling with the affairs with humans, mythological characters and folktales–but Lord uses these elements in unexpected ways, except for the ending, which is satisfying in its predictability. Her style of fantasy is smart, inventive, and innovative. I look forward to Lord’s next book.

Graphic Stories, Unwrapped!

The fifth in our series of Hugo Voting articles (short story, novelette, novella, and related work preceding) is Best Graphic Story. Like Best Novel and Best Related Work, these books are rarely available online for free, but that is not without exception. Although the Hugo committee is likely to make novels, novellas, novelettes and short stories available for free for convention attendees and sponsors (a supporting membership is only $50), we do not believe graphic novels will be included in that reader packet. Consequently, you will need to find some online (two are free) and purchase/borrow/check out others, if you want to read them all.

The fifth in our series of Hugo Voting articles (short story, novelette, novella, and related work preceding) is Best Graphic Story. Like Best Novel and Best Related Work, these books are rarely available online for free, but that is not without exception. Although the Hugo committee is likely to make novels, novellas, novelettes and short stories available for free for convention attendees and sponsors (a supporting membership is only $50), we do not believe graphic novels will be included in that reader packet. Consequently, you will need to find some online (two are free) and purchase/borrow/check out others, if you want to read them all.

-

Digger, by Ursula Vernon is a webcomic, so may be read online for free. If you’d rather own the paper comic, each volume is about ten bucks, give or take, on Amazon.

-

Schlock Mercenary: Force Multiplication is also online for free and begins here. Although dead tree versions of Schlock Mercenary are available, Force Multiplication does not seem to be in print, yet.

-

Locke & Key Volume 4: Keys To The Kingdom, is in print, and the nominated volume 4 may be found at your local comic book shop or on Amazon or in electronic format on Comixology. If you’d like to start from the beginning, get volume 1.

-

Fables Vol 15: Rose Red also does not appear to be available online. Volume 15 is $12, or you could start the whole series in dead tree or Kindle formats. The ebooks are formatted only for the Kindle Fire or Kindle for Android, however.

-

The Unwritten (Volume 4): Leviathan is also available in print and Kindle editions, but volume 4 (the volume that was nominated) is only available in print, so far.

If any more of these volumes become available for free online, we will update this post.

Links to all of the award winning novels are, as always, available through BookTrackr.

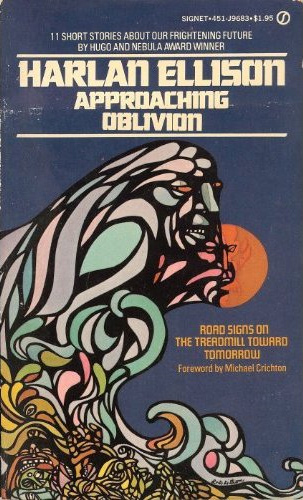

GMRC Review: Approaching Oblivion by Harlan Ellison

Harlan Ellison is one of those writers I not only love to hate but hate to love, one of those irascible writers who will permit no criticism of his work to sink in to any depth of his soul. He is also one of those wildly creative writers who is inexplicably able to form fictional worlds entirely different from one another both in setting (hard enough) and tone (nearly impossible). His progressivist politics and often blasphemous hatred of religion infuriates me, but in a seven page tour of a dying earth he can reduce me nearly to tears. Ellison has developed a powerful level of artistic talent, and he is not someone to be taken lightly. Many of the videos of the man one finds online too often depict him simplistically as an old crank—which, to be sure, he is—but this can scarcely explain the stories that could only come from a soul which feels deeply.

Harlan Ellison is one of those writers I not only love to hate but hate to love, one of those irascible writers who will permit no criticism of his work to sink in to any depth of his soul. He is also one of those wildly creative writers who is inexplicably able to form fictional worlds entirely different from one another both in setting (hard enough) and tone (nearly impossible). His progressivist politics and often blasphemous hatred of religion infuriates me, but in a seven page tour of a dying earth he can reduce me nearly to tears. Ellison has developed a powerful level of artistic talent, and he is not someone to be taken lightly. Many of the videos of the man one finds online too often depict him simplistically as an old crank—which, to be sure, he is—but this can scarcely explain the stories that could only come from a soul which feels deeply.

Too often Ellison’s wrath gets the better of him. “Knox,” the first story in this collection, depicts a liberal’s wet dream of a conservative racist party turning violent and creating a police state. Does Charlie Knox hate every person who is not wholly like himself, or is it truly himself that he hates?, Ellison asks, rather uninterestingly. The way in which Knox memorizes and recites his list of racial slurs might be revelatory in subtler hands, but with Ellison it comes off as a paranoid delusion. The great irony, though, is that Knox is revealed in the end to be telepathically manipulated by alien invaders who wish to destroy our civilization. And the worst irony is that Ellison probably didn’t understand the irony at all.

Other times Ellison’s penchant for wallowing in the bizarre and perverse gets the better of him, as in “Catman.” This is a story—if an incoherent narrative set in a incohesive future world can be called a story—which would be better left on the cutting floor, but which (I must suspect) Ellison furiously refused to trash simply because a friend recommended that course of action. Alternatively, one wonders if he wrote this story about freakishly Oedipal, immortal, machine-humping characters on a dare. There are discrete elements of creativity within the story which would be the envy of science fiction masters, but which are smashed together with such violence as to nullify any spark of humanity. The less said about it the better.

Even so, there are stories here which are worth tracking down at any cost. “Paulie Charmed the Sleeping Woman” is astoundingly different from Ellison’s usual approach, being the story of a saxophone player grieving for a dead lover, and his attempt to reach her from beyond the grave. “One Life, Furnished in Early Poverty” is a nostalgic look back at the influences that make us what we are as adults, and is haunting enough that I can forgive the time-travel conceit (well, mostly). “Hindsight: 480 Seconds” is a wistful look back at the Earth humanity is leaving behind, wondering what we could have done better, and what we still might. These are the stories which make one suspect Ellison of a hidden lycanthropic condition: the moon is new, and darkness consumes his soul; it is full, and he beholds the beauty of the night; it wanes, and he sleeps.

Even so, there are stories here which are worth tracking down at any cost. “Paulie Charmed the Sleeping Woman” is astoundingly different from Ellison’s usual approach, being the story of a saxophone player grieving for a dead lover, and his attempt to reach her from beyond the grave. “One Life, Furnished in Early Poverty” is a nostalgic look back at the influences that make us what we are as adults, and is haunting enough that I can forgive the time-travel conceit (well, mostly). “Hindsight: 480 Seconds” is a wistful look back at the Earth humanity is leaving behind, wondering what we could have done better, and what we still might. These are the stories which make one suspect Ellison of a hidden lycanthropic condition: the moon is new, and darkness consumes his soul; it is full, and he beholds the beauty of the night; it wanes, and he sleeps.

I don’t know what to make of this collection. It is distinctively bi-polar, and one must use discretion in approaching its individual parts. I suppose I must recommend it, but with all the cautions listed above intact. Ellison is a wild beast, but now and then you may find him in a sanguine, or at least tolerable, mood.

GMRC Review: The Golden Apples of the Sun and Other Stories

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s third featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s third featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun and Other Stories (1990) contains short stories from two of his previous works: one by the same name, published in 1953, and R is for Rocket, published in 1962. This reprint contains all of the stories from R is for Rocket and eighteen of the original twenty-two stories in the previous edition of Golden Apples. (The two collections had a couple of stories in both.)

Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun and Other Stories (1990) contains short stories from two of his previous works: one by the same name, published in 1953, and R is for Rocket, published in 1962. This reprint contains all of the stories from R is for Rocket and eighteen of the original twenty-two stories in the previous edition of Golden Apples. (The two collections had a couple of stories in both.)

The stories from the original Golden Apples demonstrate the range of Bradbury’s writing. Many of them were originally published in mainstream publications, such as The New Yorker, Esquire, The Saturday Evening Post, and Colliers, and don’t demonstrate any science fiction or fantasy elements. They do, however, convey a sense of wonder and otherness. Because of this, many of them were recycled for HBO’s 1980s series, Ray Bradbury Theater. The strongest of these stories seem very current. “I See You Never” recounts the deportation of a Mexican immigrant who had overstayed his visa. “Sun and Shadow” is set in Mexico and explores a poor homeowner’s objection to his house being used as “local color” in the photos of an American fashion photographer. The protagonist in “The Murderer” reacts to modern technology in the same way that many of us wish we could. The murderer in “The Fruit in the Bottom of the Bowl” worries about leaving evidence behind.

The weaker stories do seem very dated. Many of them have ambiguous time settings, placed in either our past or an isolated “land that time forgot” setting. For this reason, I did not like “The Great Wide World Over There” and “Powerhouse.” I found “The Big Black and White Game” particularly puzzling. In telling about a baseball game between the white and black employees of a resort hotel, Bradbury displays that type of 1940s racism that doesn’t think it is racist. He clearly wants to denounce the overt racism of the white women in the story, but then he has the following passage, which I think is supposed to be complimentary:

"How easily the dark people had come running first, like those slow-motion deer and antelopes in those African moving pictures, like things in dreams. They came like beautiful brown, shiny animals that didn’t know that they were alive, but lived. And when they ran and put their easy, lazy, timeless legs out and followed with their big sprawling arms and loose fingers, and smiled blowing in the wind, their expressions did not say, ‘Look at me run, look at me run.’ No, not at all. Their faces dreamily said ‘Lord, but it’s sure nice to run…’"

Many reviews of “The Big Black and White Game” commend Bradbury for writing a story about racial tensions. I also learned that the story was chosen for Best American Short Stories in 1945. This story provides a good example of the way a dated story can jar a reader. I had trouble reconciling the author of Fahrenheit 451 to the author of this story. (This experience is making me add The Martian Chronicles to my list. I’m ashamed to say that I’ve never read it, but I’ve always seen it characterized as a book that exposes prejudice and racism.)

The new edition of Golden Apples does not indicate that the reader is moving from the earlier The Golden Apples of the Sun to R is for Rocket, but it does include Bradbury’s 1962 introduction to the latter book. He writes: “This is a book then by a boy who grew up in a small Illinois town and lived to see the Space Age arrive, as he hoped and dreamt it would.” This “book” is much more cohesive than the earlier section containing the Golden Apples stories. It tells about rocket ships, space colonies, and time travel (intended and unintended, physical as well as mental). Many of the stories deal with family and space travel: “R is for Rocket” and “Rocket Man” charmingly demonstrate the sacrifices that families make when one of their members decides to travel to the stars; “The Strawberry Window” shows how colonists cope with being away from home. “The Sound of Thunder” is Bradbury’s eerie story that presents the “butterfly effect” though time travel. William Contento’s index lists this story as the most reprinted and anthologized science fiction story. “Frost and Fire” is a novelette-length story of survivors who crash on a planet with extreme temperatures and high radiation. At the beginning of the story, a boy, Sim, is born with all his faculties and senses intact. He has a clear racial memory telling him that he will grow and live and die in eight days. Bradbury’s structure and premise are strong here, and I found this story much more satisfying than many of the others.

The new edition of Golden Apples does not indicate that the reader is moving from the earlier The Golden Apples of the Sun to R is for Rocket, but it does include Bradbury’s 1962 introduction to the latter book. He writes: “This is a book then by a boy who grew up in a small Illinois town and lived to see the Space Age arrive, as he hoped and dreamt it would.” This “book” is much more cohesive than the earlier section containing the Golden Apples stories. It tells about rocket ships, space colonies, and time travel (intended and unintended, physical as well as mental). Many of the stories deal with family and space travel: “R is for Rocket” and “Rocket Man” charmingly demonstrate the sacrifices that families make when one of their members decides to travel to the stars; “The Strawberry Window” shows how colonists cope with being away from home. “The Sound of Thunder” is Bradbury’s eerie story that presents the “butterfly effect” though time travel. William Contento’s index lists this story as the most reprinted and anthologized science fiction story. “Frost and Fire” is a novelette-length story of survivors who crash on a planet with extreme temperatures and high radiation. At the beginning of the story, a boy, Sim, is born with all his faculties and senses intact. He has a clear racial memory telling him that he will grow and live and die in eight days. Bradbury’s structure and premise are strong here, and I found this story much more satisfying than many of the others.

In general, this collection seems uneven. There are great stories, weak stories, and dated stories—some are genre fiction; others are more mainstream. The R is for Rocket part is certainly stronger. The stories are better, and they seem to fit together. However, three of my four favorites come from the Golden Apple part of the book. These are “Sun and Shadow” and “The Fruit at the Bottom of the Bowl,” which are not science fiction stories at all, and “The Murderer,” which centers on technology in the “future” and seems very much like now. This book has made me want to read more Bradbury.

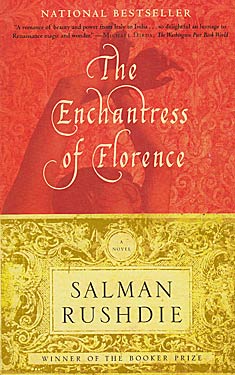

Outside the Norm: Salman Rushdie’s The Enchantress of Florence

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

When I thought about authors whom I might read for this blog, Salman Rushdie never came to my mind. The Enchantress of Florence has been on my to-read stack for a while and I vowed to read it this year, but I never thought that I’d write about it here. A few things occurred in a wonderfully serendipitous way that led me to write this blog. First, my blog about Margaret Atwood’s novels produced an interesting discussion about the label “science fiction” and started me thinking about what that label means.

When I thought about authors whom I might read for this blog, Salman Rushdie never came to my mind. The Enchantress of Florence has been on my to-read stack for a while and I vowed to read it this year, but I never thought that I’d write about it here. A few things occurred in a wonderfully serendipitous way that led me to write this blog. First, my blog about Margaret Atwood’s novels produced an interesting discussion about the label “science fiction” and started me thinking about what that label means.

Second, I recently read an anecdote from Brian Aldiss in which he recounts that he, Arthur C. Clarke, and Kingsley Amis were on a panel to give an award for best science fiction novel. These prestigious panelists chose Salman Rushdie’s first novel Grimus as the winner, but the publisher pulled the book at the last minute because they did not want Rushdie to be pigeonholed as a science fiction writer. Aldiss discusses this in an article, “Why Don’t We Love Science Fiction,” by Bryan Appleyard in The London Sunday Times (Dec. 2, 2007). Aldiss supports the publisher’s actions, saying that if Rushdie had “been labeled a science-fiction writer… nobody would have heard of him again.” I’m not sure that I agree that Rushdie would have been doomed to obscurity, but I keep running across the fact that science fiction writing is not bad writing, but the label is a bad label. Aldiss goes on to discuss the fact that the British embrace fantasy novels as books written for children that it’s okay for adults to read (ex. Tolkien, Pullman, Pratchett, Rowling), while they see science fiction as “adolescent” in the pejorative sense.

This claim, finally, leads me back to The Enchantress of Florence: it is fantasy, but fantasy written for adults. So, what do we do with it? Call it magic realism to legitimize it? We could, but this novel is different from Rushdie’s other novels that I’ve read and do consider to be magic realism. My main argument against the magic realism category is The Enchantress of Florence contains no hint of a modern setting. From the beginning, it immerses the reader in a world that is a magical past and stays there. Do I think that it belongs on the F&SF shelves on my local bookstore? Maybe, maybe not, but I do think that it is the kind of book that many WWEnders would enjoy but might not immediately pick up. (Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, his only book in the WWE database, shows only eleven readers.)

Like many of Rushdie’s works, The Enchantress of Florence juxtaposes East and West. Its historical settings are the court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar the Great and the Renaissance Florence of the de Medicis and Machiavelli. These two settings are linked by the arrival of a blond stranger in Akbar’s city of Fatehpur Sikri. This stranger is a Florentine, pretending to be Queen Elizabeth’s ambassador. (How this comes about makes an interesting start to the novel.) Once that disguise is exposed the stranger begins calling himself by the alias the Mogor dell’Amore (the Mughal of Love). Through this persona, he gains access to Akbar. He says that he has come to tell Akbar a story: “All men needed to hear their stories told. He was a man, but if he died without telling the story he would be something less than that, an albino cockroach, a louse” (89). This story concerns Akbar’s great aunt, the sister of his grandfather. Her name was Qara Köz, and she had been erased from Mughal history. As a young girl, she was a pawn in her brother’s political chess game. She and her sister were given as hostages to the enemy. When she made the choice to remain with her captor, rather than returning to her brother’s court with her sister, her brother, Babar, begins a campaign to erase all traces of her from her native culture.

While unknown in her homeland because of this, she becomes famous in other parts of the world because of her beauty. That beauty evokes power over all men who come in contact with her. Her maid servant, known as the Mirror, is only slightly less beautiful than she is. Here is the experience of one admirer:

“the women coming down toward him were more beautiful than beauty itself, so beautiful that they redefined the term, and banished what men had previously thought beautiful into the ranks of dull ordinariness. A fragrance preceded them down the stairs and wrapped itself around his heart.” (258)

Her beauty is her magic, which she uses to make her way through the world from India to Persia to Anatolia to Florence to the New World, always under the protection of powerful men.

The Mogor dell Amore’s recounting of Qara Köz’s story resembles the tale of The Thousand and One Nights. He portions out his story with digressions and necessary back stories to Akbar, and as he does so, he becomes more and more valuable to the emperor. He is not Scheherazade, telling stories to save his life. Instead he tells the story to find his own place in the world; he is a wanderer looking for a home and implicit in the story he tells is the message that the Mughal empire is his home. However, Rushdie does not model the format of the novel on The Thousand and One Nights. It is not a frame story that focuses on each part of the story as a separate story. Instead, Mogor dell Amore’s story is woven into the narrative of Akbar’s world, which is peopled with trusted advisors, rebellious sons, and multiple wives.

One of these wives, Jodha is particularly interesting, as she sets one of the novel’s themes, man’s search for the “perfect” woman. Jodha is Akbar’s “imaginary wife, dreamed up by Akbar in the way that lonely children dream up imaginary friends, and in spite of the presence of many living, if floating, consorts, the emperor was of the opinion that it was the real queens who were the phantoms and the nonexistent beloved who was real” (27). His other wives, of course, are jealous of Akbar’s phantom favorite, especially since they claim that he built her “by stealing bits of them all” (45). The only woman he wants is a woman who is not. In her well-considered review of the book, Ursula K. Le Guin points out that all the women in the book are “all stock figures, females perceived solely in relation to the male.” While Le Guin is absolutely correct, women’s power in the book comes through the stereotyped arenas of sex or magic; the men are not any better developed and fall into typical roles of mercenary, trickster, king, despot, etc. I believe that this is because Rushdie is trying to tell a fairy story about history and fable and the fine line between them. The Florentine mercenary, Antonino Argalia, is one of my favorite characters. He becomes a Janissary, fighting for Islam’s most powerful leaders and gains so much power that he can command his own mobile community. Among his loyal followers are gigantic Swiss albino brothers–Otho, Botho, Clotho, and D’Artagnan.

One of these wives, Jodha is particularly interesting, as she sets one of the novel’s themes, man’s search for the “perfect” woman. Jodha is Akbar’s “imaginary wife, dreamed up by Akbar in the way that lonely children dream up imaginary friends, and in spite of the presence of many living, if floating, consorts, the emperor was of the opinion that it was the real queens who were the phantoms and the nonexistent beloved who was real” (27). His other wives, of course, are jealous of Akbar’s phantom favorite, especially since they claim that he built her “by stealing bits of them all” (45). The only woman he wants is a woman who is not. In her well-considered review of the book, Ursula K. Le Guin points out that all the women in the book are “all stock figures, females perceived solely in relation to the male.” While Le Guin is absolutely correct, women’s power in the book comes through the stereotyped arenas of sex or magic; the men are not any better developed and fall into typical roles of mercenary, trickster, king, despot, etc. I believe that this is because Rushdie is trying to tell a fairy story about history and fable and the fine line between them. The Florentine mercenary, Antonino Argalia, is one of my favorite characters. He becomes a Janissary, fighting for Islam’s most powerful leaders and gains so much power that he can command his own mobile community. Among his loyal followers are gigantic Swiss albino brothers–Otho, Botho, Clotho, and D’Artagnan.

These names and other little gems demonstrate Rushdie’s humor and style. The sentences are lush and inventive, all the while giving the reader a knowing wink. An example of this occurs when Rushdie describes the ways that the Mogor dell Amore’s story of Qara Köz filters through the citizens of Akbar’s city:

“As the story of the hidden princess began to spread through the noble villas and common gullies of Sikri a languid delirium seized hold of the capital. People began to dream about her all the time, women as well as men, courtiers as well as guttersnipes, sadhus as well as whores…. She even bewitched the queen mother Hamida Bano, who ordinarily had no time for dreams. However, the Qara Köz who visited Hamida Bano’s sleeping hours was a paragon of Muslim devotion and conservative behavior. No alien knight was allowed to sully her purity.” (197)

The Qara Köz who visits Hamida Bano’s sister-in-law, Old Princess Gulbadan, in her dreams, is quite different:

“a free-spirited adventuress whose irreverent, even blasphemous gaiety was a little shocking but entirely delightful… Princess Gulbadan would have envied her if she could, but she was having too much fun living vicariously through her several nights a week.” (197)

If you enjoyed these sentences, you will enjoy The Enchantress of Florence. If you didn’t, you won’t. It’s that simple.

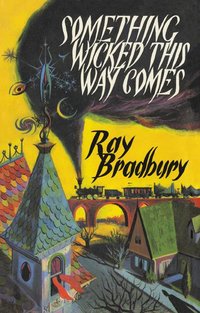

GMRC Review: Something Wicked This Way Comes

Well, you’ve got to grant that Ray Bradbury is not a boring novelist. The entire story of Something Wicked This Way Comes runs almost entirely on enthusiasm. Part morality tale and part freak show, Something Wicked finds something of a happy medium as an exuberant young adult novel, a wild and unstoppable train of delight in every moment of living. The two protagonists Jim and Will live unimpeded lives without any great danger until the day the Dark Train arrives in the middle of the night, at the witching hour. Unfortunately, Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show offers more than mere curiosities and entertainments: it offers your heart’s desire… for a price. Are you looking for true love? Your lost youth? Cooger & Dark will give it to you, just take a short ride on this carousel over here.

Well, you’ve got to grant that Ray Bradbury is not a boring novelist. The entire story of Something Wicked This Way Comes runs almost entirely on enthusiasm. Part morality tale and part freak show, Something Wicked finds something of a happy medium as an exuberant young adult novel, a wild and unstoppable train of delight in every moment of living. The two protagonists Jim and Will live unimpeded lives without any great danger until the day the Dark Train arrives in the middle of the night, at the witching hour. Unfortunately, Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show offers more than mere curiosities and entertainments: it offers your heart’s desire… for a price. Are you looking for true love? Your lost youth? Cooger & Dark will give it to you, just take a short ride on this carousel over here.

It’s easy for a reader to lose the overall geography of the novel in favor of its individual parts. Bradbury’s prose oozes with flamboyance and a baroque explosion of literary decoration. Consider this description of a library from the second chapter:

Out in the world, not much happened. But here in the special night, a land bricked with paper and leather, anything might happen, always did. Listen! and you heard ten thousand people screaming so high only dogs feathered their ears. A million folk ran toting cannons, sharpening guillotines; Chinese, four abreast, marched on forever. Invisible, silent, yes, but Jim and Will had the gift of ears and noses as well as the gift of tongues. This was a factory of spices from far countries. Here alien deserts slumbered. Up front was the desk where the nice old lady, Miss Watriss, purple-stamped your books, but down off away were Tibet and Antarctica, the Congo. There went Miss Wills, the other librarian, through Outer Mongolia, calmly toting fragments of Peiping and Yokohama and the Celebes. Way down the third book corridor, an oldish man whispered his broom along in the dark, mounding the fallen spices…

Arguably, the overall body of the novel takes second place to its members. Bradbury’s prose is such a delight to read that you might find yourself surprised to see a story wrapping itself up in the final chapters.

Arguably, the overall body of the novel takes second place to its members. Bradbury’s prose is such a delight to read that you might find yourself surprised to see a story wrapping itself up in the final chapters.

But what is this novel? A horror story? An allegory of sin and temptation? An exercise in literary gluttony? I would suggest that it’s a little bit of each. The moral, insofar as there is a coherent one at all, concerns the power of a sanguine attitude over the dark despair that comes in the middle of the night when you’re tossing awake in bed. The Dark People could be interpreted as embodiments of ennui or despondency, as noonday devils who twist one’s head around backwards to glare forever at what he has left behind. They feed on the unhappiness of ordinary people, and have so fed for centuries if not millennia.  The fact that laughter has such great power over Mr. Dark and his carnival freaks would support this approach to the story.

The fact that laughter has such great power over Mr. Dark and his carnival freaks would support this approach to the story.

Most of all, I think that Something Wicked is worth reading for its grab-life-by-the-tail-and-hang-on attitude. It lacks a certain type of literary quality, but makes up for it with spiritedness, like a child who creates a whole imaginative universe using only Legos and crayons. One might need to be in the right mood for this novel, but it’s not an unpleasant mood. Not unpleasant at all.

The Martian Chronicles: Essential and Still Relevant

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. Check out his review of one of the all-time classics of SF below and help us welcome him to WWEnd. Thanks, Scott!

It was fascinating to return to The Martian Chronicles over three decades after first reading it. (Ray Bradbury was the first SF writer I read as a child.) It remains beautiful, relevant, and unique.

It was fascinating to return to The Martian Chronicles over three decades after first reading it. (Ray Bradbury was the first SF writer I read as a child.) It remains beautiful, relevant, and unique.

Bradbury, in a series of linked short stories, presents the history of the exploration of Mars and the subsequent emigration and abandonment of the planet by humanity. The stories include rockets, robots, and Martians, but Bradbury clearly has no interest in scientific extrapolation regarding these SF tropes. Instead, they are used as plot device or metaphor to get at his real concerns about the state of humanity (Americans, especially), at the time he wrote these stories. In fact, if you think too much about the literal events of the book, it won’t work for you. The first Mars expeditions made up in part of yahoos who get drunk and vandalize ancient Martian artifacts? Thousands of people colonizing Mars within a couple of years of the earliest explorers reaching it, bringing with them all the trappings of life on Earth? Almost the entire human population of Mars returning en masse after seeing their home planet on fire as the result of a nuclear war?

Yet these events seem almost foreordained in the context of Bradbury’s themes, which include cultural and racial intolerance, imperialism, humanity’s propensity for violence, the consequences of ignorance, the repression of individuality, and the inability of people to learn from history. Yes, it’s a laundry list of cold war alienation, but the issues take on added relevance and added interest in the SF context. It seems that, for Bradbury, technology merely gives humanity’s unfortunate tendencies new venues in which and tools with which to manifest themselves. The arrival of humanity spreads Earth’s (actually, America’s) culture to Mars, wiping out the Martians in the process through the spread of disease–a point reminiscent of what happened to the Native Americans. Book censors and hot dog stands are not far behind…

The telepathic Martians take on different roles in different stories, serving mainly as metaphor rather than character. They serve alternately as victim, nightmare, conscience, oracle, empath, and mirror. They are projections of us and, at the end of the book, we must become them, if there is to be a future for humanity.

The telepathic Martians take on different roles in different stories, serving mainly as metaphor rather than character. They serve alternately as victim, nightmare, conscience, oracle, empath, and mirror. They are projections of us and, at the end of the book, we must become them, if there is to be a future for humanity.

Not every story is up to the level of the half-dozen classics in the book, but each does make a contribution to the theme. The format allows Bradbury to make use of his forte–the emotional punch of the short story–while building theme and resonance as in a novel. When I began rereading, I suspected that The Martian Chronicles might not be as good as I remembered, but I think it may be even better, though in ways I probably didn’t see back in the ’70s. Other Bradbury short stories from the late ’40s and ’50s reach the same heights as those in this book, but the added resonance of the links between them makes this the essential Ray Bradbury book. An enduring contribution to SF and to American literature!

Full Details

Full Details