Forays into Fantasy: William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, in an attempt to understand the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

In an earlier Foray into Fantasy, I looked at William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland (1908) as an influential early precursor of the weird tale, a difficult-to-define subgenre of fantasy portraying incursions of the inexplicable or uncanny into our consensual reality. Since then, I’ve been looking forward to reading The Night Land (1912), Hodgson’s fourth and final novel, which, though sometimes cited as his masterpiece, is not as often read today due to its length and distracting pseudo-archaic English. While it certainly has touches of the weird, The Night Land is also an amalgamation of fantasy, science fiction, horror, and romance, its uniqueness compounded by its extremely unusual narrative viewpoint.

In an earlier Foray into Fantasy, I looked at William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland (1908) as an influential early precursor of the weird tale, a difficult-to-define subgenre of fantasy portraying incursions of the inexplicable or uncanny into our consensual reality. Since then, I’ve been looking forward to reading The Night Land (1912), Hodgson’s fourth and final novel, which, though sometimes cited as his masterpiece, is not as often read today due to its length and distracting pseudo-archaic English. While it certainly has touches of the weird, The Night Land is also an amalgamation of fantasy, science fiction, horror, and romance, its uniqueness compounded by its extremely unusual narrative viewpoint.

The first chapter tells of the courtship and marriage of Mirdath and the unnamed narrator. Based on the writing style and details of the setting, it seems to take place in England in the seventeenth century, though this is not specified. When Mirdath dies in childbirth, the narrator, who idealized his wife with an intense degree of sentimentality, is plunged into despair. Somehow, whether through some form of clairvoyant reincarnation or psychic time travel (the ambiguous possibility of both mystical and science fictional interpretations is characteristic of the novel), he finds himself occupying the mind of a young man living on the dying earth millions of years in the future, after the sun has stopped emitting visible light, and humanity has retreated into the “Great Redoubt”—a giant metal pyramid powered by the “Earth Current” and protected from the malevolent forces of the Night Land by a sort of force field. The remainder of the novel is narrated from the perspective of this seventeenth century Englishman, now with the knowledge of the young man of the future whose mind he co-occupies, describing this future dying earth and his quest to regain his lost love—a journey through a blighted landscape teeming with evil creatures.

Forays into Fantasy: The House on the Borderland by William Hope Hodgson

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

The House on the Borderland (1908), by William Hope Hodgson, is an early and influential example of the strand of the fantastic known as weird fiction, most famously exemplified by the stories published in Weird Tales magazine from 1923 to 1954, by writers such as H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Bloch, and Fritz Leiber. (The magazine has been revived several times since, and is about to be relaunched yet again under new ownership.) I’ve been making my way slowly through Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s massive new anthology, The Weird: A Compendium of Dark and Strange Stories, which is highly recommended for anyone looking for an entry into this branch of fantasy. It traces the development of the subgenre over the last century, the earliest examples having begun appearing at about the same time as Hodgson’s novel, which is mentioned in the introduction as a key early progenitor of the weird tale. Recently, China Miéville, M. John Harrison, and other like-minded writers have promoted what they call the “New Weird,” as a modern incarnation of the form.

The House on the Borderland (1908), by William Hope Hodgson, is an early and influential example of the strand of the fantastic known as weird fiction, most famously exemplified by the stories published in Weird Tales magazine from 1923 to 1954, by writers such as H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Bloch, and Fritz Leiber. (The magazine has been revived several times since, and is about to be relaunched yet again under new ownership.) I’ve been making my way slowly through Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s massive new anthology, The Weird: A Compendium of Dark and Strange Stories, which is highly recommended for anyone looking for an entry into this branch of fantasy. It traces the development of the subgenre over the last century, the earliest examples having begun appearing at about the same time as Hodgson’s novel, which is mentioned in the introduction as a key early progenitor of the weird tale. Recently, China Miéville, M. John Harrison, and other like-minded writers have promoted what they call the “New Weird,” as a modern incarnation of the form.

Both the VanderMeers and Michael Moorcock, in his “Foreweird” to the same book, avoid providing a precise definition of weird fiction, making the point that this slipperiness is part of its appeal. According to Moorcock: “In popular terms, it came to mean a supernatural story in something of the Gothic tradition… We’re [now] clearly comfortable with a term covering pretty much anything from absurdism to horror, even occasionally social realism.” While deriving somewhat from the Gothic tradition (more on that in a future post), the VanderMeers point out that Lovecraft himself defined the weird tale as “a story that does not fall into the category of traditional ghost story or Gothic tale” of the 1800s. “Instead, it represents the pursuit of some indefinable and perhaps maddeningly unreachable understanding of the world beyond the mundane… through fiction that comes from the more unsettling, shadowy side of the fantastic tradition.” To my mind, stories in the weird fiction tradition evoke the uncanny.

It’s difficult to define, but once you’ve experienced it, you’ll know it when you read it. Most aficionados seem to agree that William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland is a good place to start. Lovecraft and Miéville, among many others, have lauded Hodgson’s work, and this short novel is a clear precursor to the even more influential Lovecraft. As in much of Lovecraft, the story is centered on the idea that there is an unseen world that threatens to leak into our reality. The nature of this foreign dimension and its denizens is never really understood. It seems to represent a threat, but is also a source of wonder. It occurs to me that the introduction of this type of story into literature early in the twentieth century is a response to a growing feeling at the time that the old certainties were giving way, change was accelerating, and the world was becoming ever more chaotic and incomprehensible, and indifferent. The continuing appeal of this branch of the fantastic could testify to the fact that this feeling has certainly not gone away.

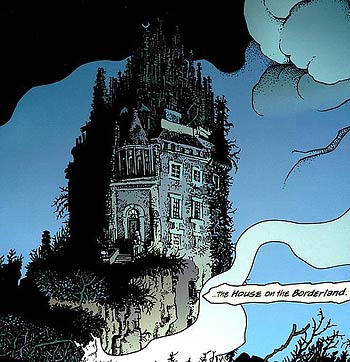

The novel begins in 1877. Two men on a fishing vacation in western Ireland come across the ruins of a large house next to a water-filled pit in a now wild but once-cultivated grove in an otherwise barren landscape. They take away a musty manuscript found in the ruins and, unable to shake off a feeling of dread and danger that seems to arise from the grove, do not return. The vacationers’ discovery of the manuscript in the first chapter, and their investigation in the final chapter into the reliability of what they’ve read, frame our reading of the first-person manuscript, which makes up most of the novel. The framing chapters provide evidence that seems to verify at least some aspects of the narrative, written by the final owner of the house, which might otherwise be dismissed as dream or hallucination. (The framing device is similar to that in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw — another first person account of the supernatural — but in this case, the framing narrators clearly come to be convinced by the account they are reading.)

The novel begins in 1877. Two men on a fishing vacation in western Ireland come across the ruins of a large house next to a water-filled pit in a now wild but once-cultivated grove in an otherwise barren landscape. They take away a musty manuscript found in the ruins and, unable to shake off a feeling of dread and danger that seems to arise from the grove, do not return. The vacationers’ discovery of the manuscript in the first chapter, and their investigation in the final chapter into the reliability of what they’ve read, frame our reading of the first-person manuscript, which makes up most of the novel. The framing chapters provide evidence that seems to verify at least some aspects of the narrative, written by the final owner of the house, which might otherwise be dismissed as dream or hallucination. (The framing device is similar to that in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw — another first person account of the supernatural — but in this case, the framing narrators clearly come to be convinced by the account they are reading.)

The manuscript’s unnamed narrator, referred to by Hodgson (in the guise of the manuscript’s editor) as The Recluse, has bought the property, knowing its evil reputation, as a refuge from the world which, we eventually learn, he has abandoned out of grief over the death of a lover.

“The peasantry, who inhabit the wilderness beyond, say that I am mad. That is because I will have nothing to do with them. I live here alone with my old sister, who is also my housekeeper. We keep no servants—I hate them. I have one friend; a dog… I have heard that there is an old story, told amongst the country people, to the effect that the devil built the place. However, that is as may be. True or not, I neither know nor care, save as it may have helped to cheapen it, ere I came.”

Just as its evil reputation cheapens the house, the Recluse’s grief seems to cheapen his estimation of his own life. After a manifestation of his lost love is revealed to him, he becomes willing to observe and tolerate all the other supernatural forces and experiences thrown at him, in the hope of finding her again.

The house is on the border between our reality and what might be another dimension, or might be manifestations of Heaven and Hell. Evil dwells in the Pit under the house, and comes spilling out in the form of a swarm of half-man half-pig “Swine-things,” who invade the grove and attack the house. In a suspenseful series of chapters, The Recluse repels the siege by fortifying the house, relying on his well-stocked arsenal and large chunks of masonry from the roof for defense. The motivations of these Swine-things, or the reason behind their appearance, are never explained. Is it a hostile response to the Recluse’s moving onto the property? A random eruption due to underground shifts that briefly give them a path to the surface? Ultimately, they leave as mysteriously as they arrive.

After these fantastic events play out, the Recluse experiences a series of visions that he regards as real. Time begins to speed up, and he realizes that everything around him is decaying as the world moves ever faster. The sun rises and sets at increasing speed, as years and millennia pass. His journey through time becomes a journey through space, and he witnesses the end of the Earth, the burning out of the Sun, and the final fate of the solar system! He finds his way to The Sea of Sleep, where he briefly finds his beloved again (Heaven, as opposed to the Hell of the Pit). Twice in the story, he is transported to a strange amphitheater surrounded by mountains, in the middle of which is a replica of the house, made of a jade-like material:

“Far to my right, away up among inaccessible peaks, loomed the enormous bulk of the great Beast-God. Higher, I saw the hideous form of the dread goddess, rising up through the red gloom, thousands of fathoms above me. To the left, I made out the monstrous Eyeless-Thing, grey and inscrutable. Further off, reclining on its lofty ledge, the livid Ghoul-shape showed—a splash of sinister colour, among the dark mountains.”

Who are these god-like creatures? This is just one of many questions left unanswered, but which suggest various possibilities. As Hodgson writes in the introduction: “The inner story must be uncovered, personally, by each reader, according to ability and desire.”

It is characteristic of the weird tale that these events are never rationalized. But they may still be understood. The Recluse’s cosmic journey reveals our individual insignificance in a universe practically beyond our comprehension, while the invasion of the Swine-things indicates the potential for such incomprehensible forces to impact our reality without warning. Psychologically, they remind us of the potential for the unconscious to impact human consciousness in unexpected ways. Writing those last sentences, I realize that this all sounds dry and analytical, yet the story works on a very visceral emotional level. The analysis only arises afterward upon reflection. Dreams may take on a new light when considered after waking.

It is characteristic of the weird tale that these events are never rationalized. But they may still be understood. The Recluse’s cosmic journey reveals our individual insignificance in a universe practically beyond our comprehension, while the invasion of the Swine-things indicates the potential for such incomprehensible forces to impact our reality without warning. Psychologically, they remind us of the potential for the unconscious to impact human consciousness in unexpected ways. Writing those last sentences, I realize that this all sounds dry and analytical, yet the story works on a very visceral emotional level. The analysis only arises afterward upon reflection. Dreams may take on a new light when considered after waking.

I came to Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland by way of Cawthorn and Moorcock’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels, and its inclusion in the Fantasy Masterworks series, but without any prior knowledge on my part. I do have some previous experience with weird stories by Lovecraft, Leiber, and Bradbury, and the connection to this tradition became obvious pretty quickly. Whatever his merits as a writer (a subject for another day!), I had always thought of Lovecraft as an original, but his approach is very clearly derived from Hodgson and other precursors, who in their works were tweaking an earlier Gothic tradition. (See Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” (1907) in The Weird anthology, for another example.) These are the type of connections I am always fascinated to discover.

The House on the Borderland is worth reading both as one of the first examples of the twentieth century weird tale, and for its own sake as an exciting, suspenseful, and mind-bending work of fantastic fiction. I enjoyed it enough to look into Hodgson’s other work, and will write about The Night Land (1912), as well as Hodgson himself, in a future Foray.

Next: #4 in Pringle’s Hundred Best Modern Fantasies: Grand Master Jack Williamson’s Darker Than You Think.

Full Details

Full Details