Recent Releases: The Deep Sea Diver’s Syndrome by Serge Brussolo

David Sarella works with a trusted crew. His accomplice Nadia is a gorgeous redhead dressed in black leather. Jorgo may be a bit simple-headed, but he is an excellent driver. They plan to break into an upscale jewelry store in an exclusive shopping district and empty the safe. Their immediate problem is that the sleek, black automobile they have chosen for this escapade is transforming into a shark. The metal frame has become slimy and the fish smell is unbearable. These are “stability issues,” and Nadia’s job is to monitor David, to see that he takes the proper maintenance drugs. The team is operating at a depth of 3300 feet, but they are already rising. David must complete the theft before he is forced to surface.

David is a master thief but a professional dreamer. In Serge Brussolo’s near-future Paris, mediums like David enter their dream worlds, perpetrate their crimes, and bring back their takes to the waking world. David’s dreams are informed by the pulp fiction he’s read since childhood, and the dreaming process is, as for most mediums, experienced as a plunge into ocean depths. He absconds with jewels that on the surface manifest themselves as mounds of ectoplasm, that white sticky stuff nineteenth century mediums supposedly exuded from their mouths, noses, and other orifices during séances.

But David and his fellow dreamers are not fakes. Their ectoplasmic creations, delicate a newborns, get whisked away for quarantine and testing. Once they are stable they go onto the art market, a market they have destroyed and transformed. Museums have sold off their collections of old art to junk dealers and replaced paintings and sculptures with ectolplasmic abstractions, the most accomplished of which sell in auction for millions. Our hero is not in that league. He makes a living as a minor artist whose works end up in museum gift shops. He’s more or less made his peace with that, but he is facing a crisis. Recently he’s come up empty handed after his dives, and some of what he has brought back is too feeble to make it past quarantine. His is the uncertain future of a failed artist.

Readers are left wondering for the first half of the story just what is the deal with this new art form? The descriptions of the objects are vague and not particularly appealing, but we learn that these creations make people feel good. They can make them feel really good. Even David’s tchotchkes lighten the spirits of those who collect them. A major work, like the monumental creations of Soler Mahus, can transform lives. David goes to revisit Soler’s magnum opus in its permanent public installation.

The great dream that had stopped the war had sat enthroned on Bliss Plaza for five years…It’s presence had driven up the apartment prices in the neighborhood, everyone wanting to live close to the work to benefit from its soothing emanations…residents in buildings overlooking Bliss Plaze were totally free of psychosomatic complaints. Better still: incurable diseases had completely vanished in a three hundred yard radius of the oneiric object. The lucky few lived with their windows open, naked most of the time…Those without the means to rent apartments nearby made pilgrimages to Bliss Plaza…a silent, naked crowd sprawled on the steps and grass.

As a practicing dreamer, David also knows the downside of ectoplasmic art. The objects have a shorter shelf life that of the old art. When they begin to decompose they not only stink, they become sticky and toxic. Art disposal is a growth industry, but there is a “finger in the dike” element to its struggle against a growing mountain of fetid art. And then there are the health problems faced by its creators. All that ectoplasm can never be fully expelled, and build up over time causes esophageal and pulmonary issues.

On one level, Brussolo’s novel is a satire on the distinctly Parisian vision of the starving artist in his garret, the failed genius in feverish pursuit of a vision that remains beyond his grasp. Despite his lessening powers and declining health, David cannot forsake his dream world, which is admittedly more vivid than the drab life he lives between dives. He will be willing to risk all for a final plunge to a greater depth than any dreamer has either ever attempted or lived to tell about.

The publishers describe The Deep Sea Diver’s Syndrome as a “visionary neo noir thriller.” There is a trace of marketing legerdemain here. David may be a trapped man in a system that once supported him and that now has little use for him, but Brussolo doesn’t employ the mounting tensions of David’s predicament to build suspense or a sense of panic. He creates an inventive progression of scenes that illustrate aspects of this bizarre world. The novel might better be described as “entertaining and very cerebral science fiction,” which admittedly doesn’t have the ring of ”visionary neo noir thriller.”

The good news for readers who find they like Brussolo’s technique and vision is that in France he has published somewhere in the neighborhood of 200 novels. The bad news is that this is his only work to have made its way into English, and there are no plans in place for future translations.

New Publications: The Blizzard by Vladimir Sorokin

Whenever I review of a foreign language work of speculative fiction, I find myself including a statement reflecting my certainty that readers of the work in its original language – Russian, Spanish, Estonian, whatever – have a fuller experience of its subtleties, humor, and imagery than I. That statement usually comes towards the end of the review, but with Vladimir Sorokin’s The Blizzard, I have decided to put it up front. I feel certain that his Russian readers have a – well, as I said.

Whenever I review of a foreign language work of speculative fiction, I find myself including a statement reflecting my certainty that readers of the work in its original language – Russian, Spanish, Estonian, whatever – have a fuller experience of its subtleties, humor, and imagery than I. That statement usually comes towards the end of the review, but with Vladimir Sorokin’s The Blizzard, I have decided to put it up front. I feel certain that his Russian readers have a – well, as I said.

It helps to learn that Russian readers, by the time they reach adulthood, have received a steady diet of “lost in the snow” narratives. The motif appears in fiction, verse, and folklore, and the stories almost always end poorly for their protagonists. The Blizzard opens with Dr. Garin, who is desperate to find transportation for himself and his serum to the plague-struck village of Delgoye, learning that snow has shut down the railway. It’s a set-up that will prompt Russian readers to think, “Here we go again.”

The forested, rural setting seems nineteenth century, and the frantic Dr. Garin, with his pince-nez and mustache, steps out of a Chekov story. That atmosphere continues when Dr. Garin learns that Crouper, the peasant who handles local bread deliveries, may have horses and a sleigh available. He approaches the man, who does indeed have horses. He has fifty of them. This is a reasonable number, since they are the size of partridges, and they propel his sleigh by running inside a drum. The doctor convinces Crouper to undertake the journey, which in normal circumstances would take only a few hours. The village will be saved from what we learn about this time is an outbreak of zombies caused by a virus brought back from Colombia. The dead are tunneling through the village, breaking into homes, and infecting the living. Dr. Garin does not approve of foreign travel.

Sorokin is one of the most popular contemporary novelists in Russia. His work employs fantastic elements in narratives that range from traditional science fiction to the sort of weird environment he builds in The Blizzard. It is never clear if he has set this tale in an alternate nineteenth century or some future that has devolved into a combination of new technology crippled by a collapsed infrastructure. (Thanks to another review, I learned that there are internal clues that place the story in our own present day.) One development running throughout the story is the twin phenomena of biological miniaturization and gigantism. Crouper’s tiny horses are distantly related to horses the size of small apartment blocks. These are used to haul trains that no longer have a power source. On their journey, Garin and Crouper take refuge in the home of a miller the size of a samovar. Garin has a sexual encounter with his full-sized and delectable wife. One of the men’s many road accidents occurs when a runner of their sleigh crashes into and breaks off in the nostril of a dead giant.

The details of all this are enjoyable and expertly drawn, even if their import remains vague. Dr. Garin becomes increasingly unsympathetic, his humanitarian zeal a cover for his temper, condescension, and poor impulse control. My sympathies all went to Crouper and his tender concern for his hard-working horses. You don’t have to be Russian to guess that this trip into the snow will end badly. But again I find myself wondering if a Russian reader finds all this more than a mildly entertaining curiosity.

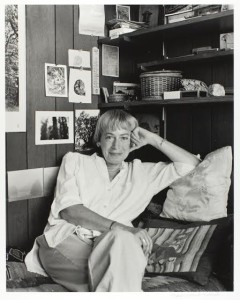

LeGuin Documentary Starts Kickstarter Campaign

Documentary filmmaker Arwen Curry has worked seven years assembling footage for Worlds of Ursula K. LeGuin. Curry has produced significant documentaries on Susan Sontag and the California architect and designer Charles Eames, but this is her most personal project. She grew up immersed in LeGuin’s fiction, and for this film she has traveled with the author to the many landscapes that inspired her fantastic worlds. Along the way she learned just “how deeply Le Guin’s otherworldly made-up places are informed by real places in the real world. She’s a very rooted writer, and person.”

Documentary filmmaker Arwen Curry has worked seven years assembling footage for Worlds of Ursula K. LeGuin. Curry has produced significant documentaries on Susan Sontag and the California architect and designer Charles Eames, but this is her most personal project. She grew up immersed in LeGuin’s fiction, and for this film she has traveled with the author to the many landscapes that inspired her fantastic worlds. Along the way she learned just “how deeply Le Guin’s otherworldly made-up places are informed by real places in the real world. She’s a very rooted writer, and person.”

This film gives us a chance to hear the LeGuin’s voice recounting her “journey of self-discovery as she comes into her own as a major feminist author, inspiring generations of women and other marginalized writers along the way.” Curry also brings in commentary by such figures as Margaret Atwood, Samuel R. Delany, and Karen Joy Fowler.

The National Endowment for the Humanities awarded Worlds of Ursula K. LeGuin a production grant, but those funds will not be released until the filmmakers raise a remaining $80,000. A Kickstarter campaign began on Februrary 1 and runs through the end of the month. It’s a chance to participate in a project that will help define the central role science fiction and speculative literature plays in American society.

Use this link to access the Kickstarter campaign.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/arwencurry/worlds-of-ursula-k-le-guin

The Universe Wants You Dead: The Return of Cosmic Horror

It’s a phrase I expect to find written in fat, drippy letters on the cover of an EC comic book from the 1950’s. Or one of the empty promises hurled at the audience in the previews for what will prove to be a predictably ordinary 1940’s horror film: Fiendish Tortures!… Ghastly Terrors!!… Cosmic Horror!!!

It is not a term I expect to find in the subtitle of not one but two current releases from New York Review Book Classics – Shadows of Carcosa, Tales of Cosmic Horror edited by D. Thin; and, The Rim of Morning, Two Tales of Cosmic Horror by William Sloane. NYRB Classics is an admirably eclectic sampling of world literature where major if obscure works of European Modernism find themselves shelved alongside noirish crime fiction of both U.S. and European vintages and the novels, memoirs and travel journals of excellent prose stylists who the editors have rightly decided deserve a fresh hearing.

But “Cosmic Horror”?

First of all, what are they talking about? And are they just trying to avoid the even pulpier term, Weird Fiction, which is, by the way, what they are talking about. Weird Fiction found its home in the classic pulp magazine Weird Tales. That magazine had a long run from 1923 – 1954 and several incarnations since, one of which remains in print. Hundreds of authors, many lost to time, appeared in the magazine, but it remains best known for the presence of H.P. Lovecraft in its early issues.

First of all, what are they talking about? And are they just trying to avoid the even pulpier term, Weird Fiction, which is, by the way, what they are talking about. Weird Fiction found its home in the classic pulp magazine Weird Tales. That magazine had a long run from 1923 – 1954 and several incarnations since, one of which remains in print. Hundreds of authors, many lost to time, appeared in the magazine, but it remains best known for the presence of H.P. Lovecraft in its early issues.

Although Lovecraft acknowledged his many forbearers, his florid, visionary style defined the genre. This new NYRB anthology quotes him on the back cover. He writes that in the true weird tale —

An atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; a hint of that most terrible conception of the human brain – a malign and particular suspension of defeat of those fixed laws of nature what are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.

Lovecraft’s was a cosmic vision, and later writing on the genre introduced and refined the term “cosmic horror.” A Wikipedia entry covers the field but has the unfortunate term “comicism” as a title. The website TV Tropes takes a more casual and entertaining approach. They offer a five-question quiz readers can use when confronting possible entries to the cosmic horror canon. Two negative answers means that you have slipped into the watered down realm of “Lovecraft Lite.”

With the first season of the HBO series True Detective, the Cosmic Horror genre wormed its way into the minds of a great swath of the American public that had probably never considered reading Lovecraft or Weird Fiction. The ritualistic murders and the decadent sect that the protagonists uncovered in the American South made references to The King in Yellow and Carcosa. Viewers and commentators rushed to the internet to unpack those references and found the peculiar 1895 work by R.W. Chambers, a popular if not particularly good writer of the time who specialized in romance novels but turned out several anthologies of weird fiction. In Chamber’s work, The King in Yellow is the name of a forbidden play, a work so diabolical that reading it, particularly reading Act Two, will drive a person mad. The play is set in Carcosa, an imaginary city Chambers borrowed from an 1891 Ambrose Bierce short story. The HBO series employs the terms divorced from any of their previous fictional uses, but weirdness and cosmic horror is all about hints and evocations. True Detective’s grand guignol set pieces and its pessimistic denouement did the tradition proud.

Shadows of Carcosa includes both the Bierce short story and a tale from the Chambers collection. It’s a chronological anthology that begins with Edgar Allan Poe and ends with Lovecraft, therefore much of what is here is “proto-weird.” It’s a progression of established tales that allows editor D. Thin to make a case for a genuine tradition. Genre fans will find mostly familiar material with a few hard-to-come-by entries, and such terror masterpieces as Poe’s “MS Found in a Bottle” or Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” are always worth rereading in a new context. For people only familiar with Dracula, Bram Stoker’s “The Squaw” proves that he was a refined purveyor or Victorian frights that had found their way into a more modern world than their Gothic predecessors. Arthur Machen is an enthusiasm I have long aspired to without ever quite attaining, but rereading “The White People” makes me want to have another go at him. Including Henry James and Walter de la Mare may be a stretch for the editor, but I am not one to complain given the quality of their stories.

This was my first encounter with M.P. Shiel, who I know wrote The Purple Cloud (1901), an apocalyptic novel kept in print by Penguin Classics. “The House of Sounds,” his story collected here, is an off-the-rails variation on the theme of a young man’s journey to the remote home of an old college friend. I am not surprised to learn that his contemporaries considered Shiel “gorgeously mad,” and that he had become a “reclusive religious maniac” by the time of his death.

Prose as feverish as Shiel’s or Lovecraft’s, and situations as extreme as those that fill these stories, ask the committed reader not to find the enterprise ridiculous. The writing at its best, or at its worst – these terms can become relative – may be bonkers, but woven through the lurid fireworks are passages effective as both visceral horror and exciting of explorations of extreme psychological states. The diarist in Poe’s “MS Found in a Bottle” is trapped on a ship blown off course and headed for oblivion. His lucidity is the last remnant of his humanity.

To conceive the horror of my sensations is, I presume, utterly impossible; yet a curiosity to penetrate the mysteries of these awful regions predominates even over my despair, and will reconcile me to the most hideous aspect of death. It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge – to some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction.

To conceive the horror of my sensations is, I presume, utterly impossible; yet a curiosity to penetrate the mysteries of these awful regions predominates even over my despair, and will reconcile me to the most hideous aspect of death. It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge – to some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction.

The two William Sloane novels from the 1930’s gathered in The Rim of Morning may seem like tame stuff compared to the stories in D. Thin’s anthology. To Walk the Night and The Edge of Running Water were Sloane’s only two novels. He wrote a few stories, edited a couple of significant sf anthologies, but spent most of his career as the director of Rutgers University Press. Stephen King writes the admiring introduction to the NYRB volume, and he lets the reader know not to anticipate the kind of horror show that we have come to expect from the genre:

Sloane builds his stories in carefully wrought paragraphs, each one clear and direct. He is a man of the old school, who learned actual grammar in grammar school…and probably Latin at the high school and college levels.

King may be weeding out the sensation seekers, but, like King, I was hooked by the first sentence of each of Sloane’s novels. These openings promise the kind of storytelling I weaned myself on as a child and still find irresistible.

The form in which this narrative is cast must necessarily be an arbitrary one. In the main it follows the story pieced together by Dr. Lister and myself as we sat on the terrace of his Long Island house one night in the summer of 1936.

To Walk the Night

The man for whom this story is told may or may not be alive.

The Edge of Running Water

Sloane’s novels bring in university settings and academic protagonists, which is not surprising given his background. In To Walk the Night, two young men making their way in the New York City financial markets return to their alma mater for a homecoming football game. When they go to visit a favorite astronomy professor, they find him seated in the chair at his telescope in the school’s observatory and burned to a crisp. (Small North Eastern colleges have observatories in these types of stories the same way college professors have elaborate laboratories in their remote country homes – see The Edge of Running Water ff.) The deceased professor had recently acquired, to his ex-students’ surprise, a young, beautiful, otherworldly wife. To the reader’s surprise, when this woman shows up in Manhattan one of the young men falls under her spell, marries her, and moves to the desert. Distressed letters from the young husband brings his friend to Cloud Mesa and sets up Sloane’s final set piece, a conclusion that proves that this director of Rutger’s University Press knew how to put on quite a show.

In The Edge of Running Water, a young science professor answers a distressed message from his mentor who has retired – in disgrace – to some New England backwater. There he continues researches that may change the way we think about life and death. That sounds like the hackneyed plot to some minor, 1940’s Universal Studios Boris Karloff vehicle, and in fact it is. You can stream it on Your Tube under its more suitable Saturday matinee title, The Devil Commands. (I recommend it on principle, not having yet watched it myself.) Sloane squeezes all the action of his final novel into a forty-eight-hours and incorporates a love interest for the young protagonist, a creepy medium whose agenda may run counter to the aging professor’s best interests, and a possible murder. What the novel lacks in suspense it makes up for in characterization and a frenzied conclusion. Sloane’s novels may appeal to only a small segment of the horror market, but they definitely have their place in the history of American fantastic literature. They are best read on rainy afternoons.

NYRB Classics have sprinkled horror and science fiction through their lists, and these two volumes are welcomed additions. Two new titles do not mark a trend, but given the depth and quality of their crime list, weird fiction, cosmic horror, or however they choose to label it is a promising field should they choose to commit to it.

Tomorrow I Will Wake Up And Scald Myself With Tea

The Taste of Cinema website has published a list of twenty Eastern European science fiction films worth checking out. Some are the expected classics, but there are possible gems here if you can track them down. The title of this posting is the title of film number 14.

NEW RELEASES: The Man Who Spoke Snakish by Andrus Kivirahk

Leemet is a young man of the forest people. When he was a child, too young to remember the experience, his parents had made the move to the village. His father learned to work the fields and even developed a taste for bread, but Leemet’s mother became bored and could not adjust to village life. This made her easy pickings for a bear, those lotharios notorious for stealing away human wives. When Leemet’s father caught his wife and her lover in flagrante delicto, the startled animal bit his head off. Leemet’s mother, subsequently abandoned by the bear, returned to the forest with her infant son.

Leemet is a young man of the forest people. When he was a child, too young to remember the experience, his parents had made the move to the village. His father learned to work the fields and even developed a taste for bread, but Leemet’s mother became bored and could not adjust to village life. This made her easy pickings for a bear, those lotharios notorious for stealing away human wives. When Leemet’s father caught his wife and her lover in flagrante delicto, the startled animal bit his head off. Leemet’s mother, subsequently abandoned by the bear, returned to the forest with her infant son.

For Leemet this has been a good thing. His life in the forest is fun and adventurous. His uncle is one of the last fluent speakers of Snakish, the language that allows humans to communicate with snakes, those wisest of forest inhabitants, and exercise control over other animals. Without Snakish, it is difficult to maintain an adequate herd of wolves, and wolves are needed for both transportation and their milk. Leemet masters the ancient language, and he spends his days with human friends his own age, his older male relatives, and the invaluable snakes who offer both advice and the warmth of their burrows in the winter. He is also friendly with the primates, an older hominid species who has not left the trees and spend most of the time breeding wood lice the size of sheep.

Andrus Kivirahk is the most popular contemporary author in Estonia, known as a satirical journalist and a bestselling novelist. This novel, which appears to take place in a fantastic version of his homeland during the early middle ages, is his first to be translated into English. It is an engaging tale of old ways giving way to modernity, filled with episodes of comic invention, family drama, young love, and the sadness of old traditions giving way to a modernity that offers much but exacts a stiff toll.

Leemet is the perfect hero for such a tale, a tenth-century, Estonian Huckleberry Finn. Despite his snakish wisdom, he can be very naïve. He perceives the armored knights that come from across the sea on their armored horses as single, metallic creatures. He is surprised to discover how relatively easy they are to kill. The obese, berobed monks who accompany them he assumes are their ever-pregnant wives.

Leemet may be naïve, but he is not stupid like those who have abandoned the forest for the village. Village dwellers, vehement about their newly acquired civilized skills and Christianity, believe all sorts of superstitious nonsense about the forest and its supposedly demonic denizens. And they rejoice in their subservience to their German-speaking masters. The village leader was taken as a young man across the sea for training in civilization and the new religion. When he speaks with pride of his time spent as the bedmate to an archbishop, Leemet cannot help but feel that there is something off about this arrangement.

But Kivirahk’s novel will be the story of sad, funny, and inevitable change. As I read it, I wondered what added resonance it had for its Estonian audience, who have taken it so to heart that a popular board game has been created around it. For English readers it is a thoroughly enjoyable historical fantasy and an introduction to a major European writer.

(I received an advanced ebook of this title from Net Galley.)

NEW RELEASES: The Night Clock by Paul Meloy

I had this as an advanced reader’s copy through Net Galley, and I went into it knowing nothing of the author or the plot. I don’t know, however, that much prior information would have helped me with the first couple of chapters. Meloy dumps us into a netherworld where the planet Mars takes the place of the moon, and characters I sensed were the good guys kept to their side of the street while a pub across the way served as a passageway for very bad things to enter their world. The next chapter involved a farm house bothered by a zombiefied relative who ate hot stew with his bare hands, had to be led away on the tines of a pitchfork, and set on fire in a field.

I had this as an advanced reader’s copy through Net Galley, and I went into it knowing nothing of the author or the plot. I don’t know, however, that much prior information would have helped me with the first couple of chapters. Meloy dumps us into a netherworld where the planet Mars takes the place of the moon, and characters I sensed were the good guys kept to their side of the street while a pub across the way served as a passageway for very bad things to enter their world. The next chapter involved a farm house bothered by a zombiefied relative who ate hot stew with his bare hands, had to be led away on the tines of a pitchfork, and set on fire in a field.

It took me several pages into the next sequence to realize that Meloy was settling down to his plot. A housing estate somewhere in the UK, with its boarded up shops, council flats, graffiti-covered walls, and threats of violence suggested a dystopian, post-apocalyptic setting, but no, this is just a miserable place to live. Meloy can really pack in the information. With the background of a mass shooting at a day care center, he introduces us to a feckless estate patrolman, an alcoholic hanging onto some sense of dignity, and a social worker whose cases have begun to either kill themselves or others. And there are monsters, hideous creatures that can possess the weak and pursue those who might be a threat to them.

Meloy has worked as a psychiatric nurse, and this section grounded in the world of the housing estate, with his hero Phil Travena dealing with suicidal and homicidal clients, a weaselly new boss brought in to “tighten the ship,” drunks and a growing sense that these monsters may not be hallucinations sets the action in both a very real and very creepy world. Once we are part of the pitched battle between good and evil, things take on the more predictable cast that such battles usually entail. But Meloy continues to create inventive situations, engaging characters, and grand set pieces. His monsters are spectacular creations that wear their debt to Lovecraft lightly. The talking animals are a problem, but that could be my inherent resistance to talking animals.

Much of the plot involves the impending birth of Chloe, a child whose existence is crucial to victory over the dark forces. In one of Meloy’s most successful narrative devices, we get to know Chloe as an adult character, stranded in a dangerous world as she waits to be born. There are also a man and his son who start as characters in a children’s book who become major players in the battle.

At times I felt that Meloy’s story needed a larger canvas than he provides, but when I weighed that against his ability to wrap things up as quickly as he did, I decided he made the right choice. He ties things up well. That illogical zombie scene from the first pages even makes sense by the time the story is over. And although he doesn’t end with cliffhangers, Meloy could easily return to this world for further novels.

Falling for Falling in Love with Hominids

This collection of stories has been my introduction to Nalo Hopkinson. I have read a few other stories in anthologies, but I’ve never settled down with one of her novels, although I have the best intentions of doing so.

This collection of stories has been my introduction to Nalo Hopkinson. I have read a few other stories in anthologies, but I’ve never settled down with one of her novels, although I have the best intentions of doing so.

Especially after having read Falling in Love with Hominids, which is a pleasure from beginning to end. All of what I have thought of as Hopkinson’s major themes are here: race, gender, feminism and the folklore of her Caribbean heritage. (Unless you are really up on your Caribbean folklore, expect to do some serious googling with a few of these stories. I learned the Jamaican slang term for off-brand sneakers among other things.)

Hopkinson writes a short introduction for each story. In one of these she remembers her response to a student worried about tactics for suspending the reader’s disbelief. Hopkinson’s advice was, “…never give them time to disbelieve.”

I think that must work, because looking over the notes I jotted down in an attempt to remember these eighteen stories, I find descriptions that sound much weirder than the stories as I experienced them.

Delicious Monster – son visits father now living with gay lover. Why is Vishnu to leave with Garuda during solar eclipse?

The Smile on the Face – St. Margaret of Antioch. Google her. Do kids still play post office?

Raggy Dog Shaggy Dog – ruthless orchid pollination

Message in a Bottle – kids with big heads travelers from our future. All species make art.

Emily Breakfast – lazy Saturday morning for gay couple. A stolen chicken. Cats can fly. Chickens breathe fire. Lizard messenger service.

Old Habits – why would one shopping mall have such a high mortality rate?

So she doesn’t give the reader time to think about all the strangeness because it surrounds you from the first sentence. Or it could also sneak up on you.

So she doesn’t give the reader time to think about all the strangeness because it surrounds you from the first sentence. Or it could also sneak up on you.

Hopkinson has contributed to the Bordertown Project, a shared world anthology begun by Terry Windling. Bordertown exists on the edge where the mundane world meets the world of magic. That actually sounds terrible to me, but “Ours is the Prettiest,” Hopkins contribution included here, navigates the terrain with grace and humor. And her description of how her protagonist made the transition to Bordertown could describe the process she puts her readers through in her own ficition.

The Change happened slowly… At some point it crossed my mind that the flashily overlit Honest Ed’s Discount Emporium seemed to have seamlessly metamorphosed into a store called Snappin’ Wizard’s Surplus and Salvage… but they were always bulldozing the old to replace it with something else… By the time I had to accept that I was no longer in Toronto and those weren’t just tall, skinny white people with dye jobs and contact lenses, it didn’t seem so remarkable. People changed and grew apart. As you aged, your body altered and became a stranger to you, and one day you woke up and realized that you were in a different country. It was just life. I hadn’t needed to travel to the Border; it’d come to me.

Hopkinson brings the border to us.

China Miéville’s Three Moments of an Explosion: How Weird Is It?

China Miéville is both a proponent and practitioner of New Weird writing. Some of you are probably ready to quit reading at this point. “New Weird” is a term that can seem both vague and unnecessary. Weird writing has its canon revolving around H.P Lovecraft and company with their themes of ancient evil and cosmic terror. Defining a new variety of weirdness can come down to a long list of writers who to greater or lesser degrees produce it – whatever exactly it is. Is it just a more explicit, visceral version of what came before, or is it marked chiefly by its effort to incorporate literary ambitions that divorce it from its pulp origins?

China Miéville is both a proponent and practitioner of New Weird writing. Some of you are probably ready to quit reading at this point. “New Weird” is a term that can seem both vague and unnecessary. Weird writing has its canon revolving around H.P Lovecraft and company with their themes of ancient evil and cosmic terror. Defining a new variety of weirdness can come down to a long list of writers who to greater or lesser degrees produce it – whatever exactly it is. Is it just a more explicit, visceral version of what came before, or is it marked chiefly by its effort to incorporate literary ambitions that divorce it from its pulp origins?

Whatever the case, it is staking out its territory in the speculative fiction arena. Anne and Jeff VanderMeer, who in 2011 established a weird canon with the 1100 page anthology, The Weird, A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories, had already in 2008 anthologized 30 stories and essays as The New Weird. This year, weirdness enters the crowded arena of annuals with Laird Barron editing The Year’s Best Weird Fiction, Volume I. (If they have come out in the past year, I assume they are “New” Weird by default.)

Miéville contributed both a story to the VanderMeers’ 2011 anthology and an “Afterweird: The Efficacy of a Worm-eaten Dictionary.” He addresses the origins of The Weird without making a specific case for the new variety, but his arguments give a good picture of how his personal vision has been formed. He starts by leading us down an etymological dead end, deriving “weird” from the Anglo-Saxon “wyrd,” a word conjuring a vision of fate and doom as a “cat’s cradle, intricate and splendid as a Sutton Hoo buckle.” He proposes that the weird could be the feral child of the wyrd, but then, in Miévillian fashion, pulls the rug from his own argument. “What if etymology is fucking useless?” Late 19th and early 20th century writers did not engage their Gothic fathers in an Oedipal struggle to develop a new language. Theirs was not a new literature of fatefulness but its rebuke.

The fact of the weird is the fact that the worldweave is ripped and unfinished. Moth-eaten, ill-made. And through the little tears, from behind the ragged edges, things are looking at us.

(You may either read that last bit as a simple declarative statement, or creep it out with internal italicization: things are looking at us.)

His verdict on the VanderMeer anthology: “This is a worm farm. These stories are worms.”

The stories in Three Moments of an Explosion can get pretty wormy. The book is not announced as an exercise in New Weirdness, but the publisher drops a hint on the back cover. We are told to expect “a cast of damaged yet hopeful seekers who come face-to-face with the deep weirdness of the world – and at times the deeper weirdness in themselves.”

Miéville titles this 400-page collection after the three paragraphs of science fiction that opens it. In an unspecified future, a crowd gathers to watch the destruction of a derelict warehouse. At the moment of the explosion, three intrepid thrill seekers ingest tachyon laced MDMA and rush into the collapsing building. They experience it in a moment outside of time. The drug begins to wear off, and only two make it out alive. But two out of three’s not bad, and the thrill was worth it.

Perhaps Miéville is letting us know that he will be slipping us the tachyon/ecstasy pill for each of the upcoming tales, leaving us wide-eyed observers suspended in his visions of collapse and morbid wonders.

To lure us in he opens with “Polynia”, a crowd pleaser about giant icebergs appearing in the sky over London. It’s an offbeat coming-of-age story that progresses from boyish adventure to adult lives lived in an irrevocably changed world.

After “Polynia,” things turn darker and tend to stay there. “Rope” is another sf story, but the mood is dour. Earth has long ago perfected the technology for space elevators, but we have not been able to keep them in good operating condition. A telling moment comes when intergalactic visitors have to feign interest in our pitifully out-of-date wonders. When he leaves sf behind, Miéville cranks up the weirdness dial in stories set in dismal worlds peopled by anxiety-ridden characters performing tasks that have lost their meaning and pursuing lives that offer no safeguards against the chaos engulfing them.

“The Buzzard’s Egg” takes place in a time of religious wars where the battles involve capturing the enemy’s god. In a remote tower, an old man tends to an old god with whom he’s grown quite fond. But the tides of war are changing. Miéville’s writing here takes on the tone of a Samuel Beckett monologue. In “Estate,” a young man, now living alone in his family’s house, is kept awake nights first by birds, then foxes, then rowdy kids. An acquaintance he hasn’t seen since his schooldays returns, and soon the old neighborhood is going up in flames. In “Keep,” the world succumbs to a disease that causes circular fissures to surround the infected. These fissures eventually swallow up entire cities, leaving the sufferer on a small island of solid ground, hence the title “Keep.” (You would probably have to read that one to have any idea what I am trying to describe.)

If you have read much Miéville, you know that it is wise to keep the dictionary app open while you proceed. “The Dusty Hat” has a dense, baroque verbal style perhaps meant to serve no other purpose than to put the reader as out of his depth as is the story’s left-leaning protagonist who slides into a phantasmagoric world of politics made corporeal. (Again, just read it.)

Since I was reviewing this book, I read it through from start to finish. Normally if I were to take up a book like this I would pick may through it, skipping around and possibly never reading every story. So for full disclosure purposes, looking back over the table of contents, I see titles that no longer mean anything to me, and I question the accuracy of my memories of other stories. What I remember most clearly is Miéville’s ability to find a new voice specific to each story. His American movie critic narrator of “Junket” is fully realized and far removed from the medical student in 1930’s Glasgow who tells the tale in “The Design.” It’s true that you are often left marveling at the author’s virtuosity rather than caring about the characters, but I don’t see that as the negative quality some readers report.

I also don’t agree that Miéville’s stories are poorly plotted and tend to wind down rather than end. They don’t wind down. The bottom falls out, taking you with it. And as Miéville said in his attempt to define the essence of Weird fiction, while in free fall you dread that you are about to learn exactly what those things are that are looking back through the holes at us.

Stories for Chip: Fellow Writers Salute Samuel R. Delany

Stories for Chip is a collection of fiction and essays in honor of Samuel R. Delany. Two ways of approaching this review suggest themselves.

Stories for Chip is a collection of fiction and essays in honor of Samuel R. Delany. Two ways of approaching this review suggest themselves.

1. Since I have read only two Delany novels and would place neither on my favorite list, I could humbly remove myself from making further comment.

2. I could consider my relative lack of first hand experience of Delany’s work as a plus when it comes to considering the stories anthologized here strictly on their own merits.

Obviously I am going to go with the second option, but I need to say something more about the first.

I read Nova and The Einstein Intersection about four years ago. Nova I didn’t particularly like for reasons I no longer clearly remember. Einstein entertained and intrigued me, although I remember not quite “getting” the end. Looking at other reader reviews, I saw that I was not alone in that response. Looking recently at a range of reader reviews I see that Delany can be a polarizing author. Encomia are balanced out by disparaging comments from those who find the work opaque or over-written. This is especially true when it comes to Delany’s big books, Dahlgren and Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand. In one of his letters, Philip K. Dick, an author I think very highly of, reports throwing his copy of Dahlgren across the room before he was a hundred pages into it. In some cases, readers are put off by Delany’s content. These negative, sometimes angry responses, combined with what I’ve read in this new book, have actually renewed my interest in going back to Delany.

I have also read a third Delany novel. When I was in the book business, a small gay publishing house needed to remainder a few hundred copies of Hogg, one of Delany’s forays into pornography. I bought them and sold them for between $10 and $50 as their number decreased. I also read it. I can’t take the time to be shocked, but it is a variety of violent, transgressive pornography that leaves me puzzled about both its purpose and its audience. But a recent edition of the Los Angeles Review of Books ran an article on Hogg, “Uses of Displeasure: Literary Value and Affective Disgust,” by Liz Janssen. Again, the jury is split.

Stories for Chip is not a collection of pastiches. The writers have apparently been chosen because they work under Delany’s influence and address his themes. I have to say “apparently” because the book comes with essentially no editorial content, and it is badly needed. This situation was worsened by the advance ebook I received from Net Galley. The Table of Contents listed a Contributors page, but it was nowhere to be found. And the transcription was the worst I have ever encountered. Words were run together, sometimesuptotheextentofanentire sentence. A couple of stories with particularly dense or playful language were unreadable.

There is a lot of very good stuff here, and even the absence of the Contributors section worked to my advantage. I knew only a fraction of these writers, and several of those only by name. Most of the stories occasioned a trip to Google, where I found information and links I would not have in the couple of sentences the book itself might have contained.

The contributors are an international, multiethnic roster whose interest in Delany shows in their attention to race and gender and the pleasure they take in language. The book was funded by an Indiegogo campaign, and the publisher’s website had an open call for submissions. Somehow I doubt that Junot Diaz, Nalo Hopksinson, Kit Reed, Michael Swanwick and a few of the others answered an open call. And then there is Thomas Disch, who died in 2008. As I said above, more editorial content is badly needed, but finally that can’t take away from the enjoyment of the 30 stories and four critical essays included.

A few personal favorites, specifically from authors I did not know:

Claude Lalumiere: “Empathy Evolving as a Quantum of Eight-Dimensional Perception.” A misanthropic human time traveler finds himself millions of years in the future. Octopi are the dominant species, and if they don’t eat you they absorb you. This sets off a change of incarnations over the eons, in one of which the cephalopod/human entity may become God.

Anil Menon: “Clarity.” A professor of computer science in India finds himself living inside one of the theoretical models he and his co-workers consider thought experiments.

Geentajali Dighe: “The Last Dying Man.” According to Hinduism, the world destroys and recreates itself in cycles involving millions of years. And yet it has to happen sometime. A man and his daughter in Mumbai find themselves dealing with the day-to-day reality of the transition.

Weslyan University Press keeps in print around 1,500 pages of Delany’s critical and theoretical writing, and he prompts a fair amount of critical writing from others. There are several essays here, but Walida Imarisha’s very personal account of her engagement with both the man and his writing best conveys the significance Delany has had on writers of color. “So long seen as the lone Black voice in commercial science fiction Delany held that space for all the fantastical dreamers of color who came after him.” She goes on to propose that she and other writers become “walking science fiction…living, breathing embodiments of the most daring futures our ancestors were able to imagine.”

She is not asking anyone to sign onto her vision, but reading Stories for Chip you see that vision in action.

Full Details

Full Details