Reading the Pulps 6: “Call Me Joe” by Poul Anderson

Read it now: Astounding Science Fiction April 1957 (from the Luminist League)

You might already own “Call Me Joe” in one of these anthologies:

- Best Science Fiction Stories and Novels 9th Series edited by T. E. Dikty

- A Century of Science Fiction edited by Damon Knight

- The Science Fiction Hall of Fame v. 2A edited by Ben Bova

- The Great SF Stories #19 (1957) edited by Asimov & Greenberg

- Masterpieces: The Best Science Fiction of the Century edited by Orson Scott Card

- Call Me Joe: The Collected Works of Poul Anderson #1

- Call Me Joe – 99 cent eBook at Amazon

Warning: This column contains spoilers.

I’ve been struggling for days to write this essay. I torture myself with self-analysis wanting to know why I keep reading these old stories. I work to build a framework for critical judgment of science fiction that keeps collapsing. I keep relearning that few people read these old stories anymore, which makes me keep asking: “Why am I making this effort?” This leads to pages and pages of theories, eventually leading to the realization the answers are too long for a single essay. So, I’ve decided to just let them leak out while I discuss a series of stories over the next few months.

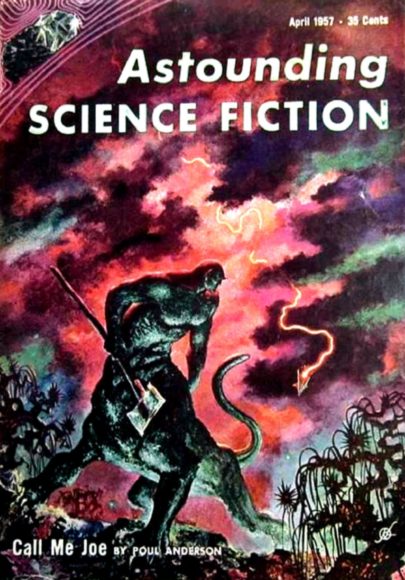

“Call Me Joe” by Poul Anderson was first published in 1957 and was selected by the Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) for inclusion in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume 2B edited by Ben Bova. Volume One and 2A have been released on audio and volume 2B is due April 10th. Listening to all these classic science fiction tales is a joy for me, but I’m haunted by the question: “Will anyone care about these old stories when old fans like me die off?”

“Call Me Joe” begins:

The wind came whooping out of eastern darkness, driving a lash of ammonia dust before it. In minutes, Edward Anglesey was blinded.

He clawed all four feet into the broken shards which were soil, hunched down and groped for his little smelter. The wind was an idiot bassoon in his skull. Something whipped across his back, drawing blood, a tree yanked up by the roots and spat a hundred miles. Lightning cracked, immensely far overhead where clouds boiled with night.

As if to reply, thunder toned in the ice mountains and a red gout of flame jumped and a hillside came booming down, spilling itself across the valley. The earth shivered.

Sodium explosion, thought Anglesey in the drumbeat noise. The fire and the lightning gave him enough illumination to find his apparatus. He picked up tools in muscular hands, his tail gripped the trough, and he battered his way to the tunnel and thus to his dugout.

It had walls and roof of water, frozen by sun-remoteness and compressed by tons of atmosphere jammed onto every square inch. Ventilated by a tiny smoke hole, a lamp of tree oil burning in hydrogen made a dull light for the single room.

Why does Edward Anglesey have four feet and a tail? And even though we are told the earth shivered, it doesn’t sound like our world at all. It’s not. We’re on Jupiter, and Edward occupies the mind of a genetically engineered animal designed to live on Jupiter. Anglesey is a man in a wheelchair working in a scientific laboratory orbiting Jupiter. With a combination of psychic powers amplified by electronic equipment Anglesey can control the being called Joe on the surface of Jupiter. When Joe is awake Edward lives in Joe’s powerful body, and when Joe sleeps Anglesey bitterly occupies his own crippled body on the space station.

In 1950s science fiction writers were imagining how humans could explore the solar system. For most writers, the gas giants were considered inhospitable to humans. Anderson wanted to find a way to explore them too. Because many science fiction writers, especially at John W. Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction assumed humans had latent psychic abilities, Anderson combined bioengineering and electronic enhanced possession to solve the problem of living on Jupiter. It’s a wonderful bit of science fictional speculation and imagination for 1957.

However, in 2018 we know there is no surface on Jupiter. We also know that humans do not have psychic powers. In 1957 “Call Me Joe” was good science fiction, in 2018 “Call Me Joe” is outdated science fiction. Modern science fiction often speculates how we could live on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, but we’ve given up on colonizing the gas giants themselves. Not all SF writers have given up on psi-powers, but no one who understands science considers ESP anything more than gimmicks for stories that appeal to childish minds.

Does this mean we should stop reading “Call Me Joe?” That’s a hard question to answer. It’s still a well-told compelling work of fiction. It’s entertaining. The first goal of writing is to sell to editors. The second goal is to sell to readers. Entertainment sells best. What makes a story last to become art involves other qualities. 99.9% of most stories don’t last. And even then, it might be overly generous to say one out of thousand stories survive the test of time.

I went to a science fiction convention this weekend looking for dealers of old books and magazines and found none. I hoped to find panels that talked about old stories and found none. Very few people read science fiction short stories anymore. For the majority of science fiction fans, they define the term by movies, television shows, games, anime, comics, role-playing, and cosplay. And I’d say most of the active science fiction readers prefer book series now. Short fiction has a declining audience.

Science fiction of 1957 is not the science fiction of 2018. In 1957 science fiction fans pursued beliefs in the future they faithfully hope science would make real. For the most part, science fiction in 2018 is a form of escape from reality. It’s a rejection of growing up. Just another fantasyland. Very little science fiction written today is about making ideas come true.

So how do we judge a dying art form? There are still science fiction writers who pursue speculation about the possible in a reality governed by science. But most fans want Star Wars. Even Star Trek has been morphed into Star Wars.

If we only consider entertainment as a measure of artistic success, popularity and sales figures are good enough yardsticks for judging. And by those measurements, the stories in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame series must have little artistic merit. This is where I’m trying to build my critical framework. Traditional art has all kinds of measures we could apply to the storytelling part of science fiction, such as how they were written, characterization, plot, theme, setting, and what they say about the times in which they were written. But what about the unique qualities of science fiction? How do we judge speculation? What makes science fiction uniquely science fiction and how do we judge it? How can we define science fiction when it becomes a catch-all for all kinds of far-out unscientific story ideas?

If we don’t consider the science in science fiction, then it’s only fiction and should be judged by the standards of all fiction. And if we do consider the science, how do we judge the science in the story, by the science of when it was written or the science of when it was read? Science fiction often speculates about realistic possibilities that eventually become probably impossibilities.

I believe “Call Me Joe” is a wonderful story about 1957 science fiction. It tells us all kinds of things about 1957 that can’t be found in history books or even Best American Short Stories 1958. If I forget that it was written in 1957, it works as a story, but the science is woefully ignorant. However, that might not be a problem for modern science fiction fans since a kind of comic book pseudo-science has taken over popular science fiction.

Science fiction has become another Disneyland. For most writers and readers, it’s always been that too. However, for a few writers and readers, it was about speculating where science had yet to statistically tabulate the odds. In 1957 there were still some long odds for psychic powers, now there’s not. Poul Anderson used those odds in a creative way. The odds haven’t played out. How do we judge his creative effort?

JWH

Full Details

Full Details

1 Comment

SF is fiction,and can be judged by the qualities that make other fiction good,as you say,but it is something different and unique.It has developed without the restraints that limit general literature,which is what makes it special.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.