Seeing the Future

I’ve been having a lot of fun collecting digital scans of old pulp magazine covers. It’s great killing time on the Facebook group, Space Opera Pulp, where several thousand other fans of pulp magazines hang out. I save images to a folder called “SF Covers” and use a program, John’s Background Switcher to randomly display them on my computer’s desktop background. (It’s a free program for Windows and Mac computers.)

Then, when I want to take a break I’ll watch a slideshow of science fiction art. Sometimes I listen to a podcast or audio books while watching. I tell JBS to switch images every 15 seconds. It’s pleasantly meditative.

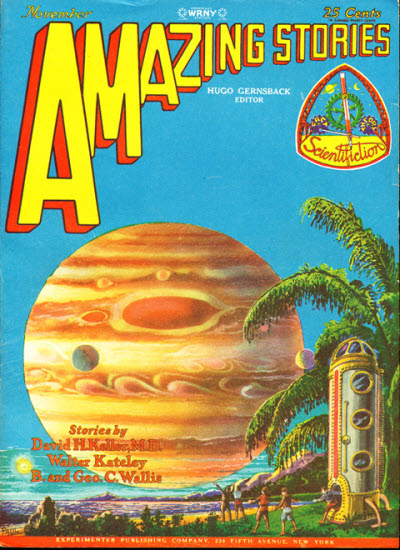

However, this activity is also proving educational. Not only am I seeing a visual history of the science fiction genre, but I’m learning how people saw the future over time. For example, the cover from Amazing Stories, November 1928 shows a rather steampunky spaceship landing on one of the moons of Jupiter. Remember, real rockets had yet to be invented.

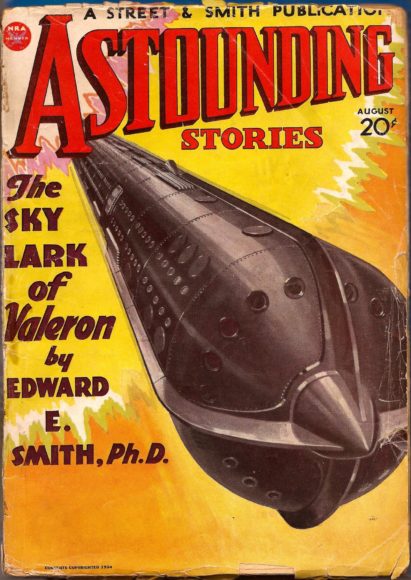

Spaceships got very weird, and very long, in the 1930s. And they also imagined some very strange machines. It’s always funny to see current-day technology adapted to look futuristic.

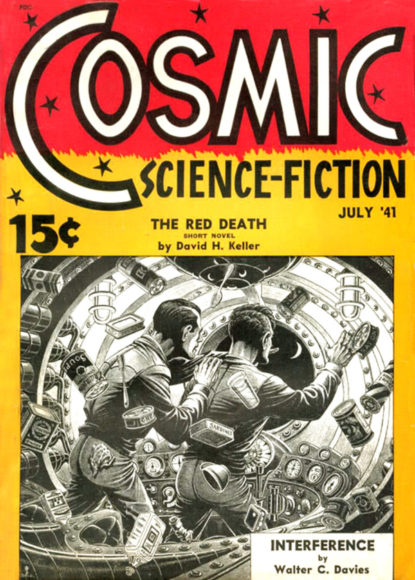

Now take a look Cosmic Science Fiction, July 1941. How many people understood the concept of weightlessness back then? I’m quite impressed with the artist here. I’m not sure if I ever read an old story that conveyed so much in words as what’s drawn here in pen and ink.

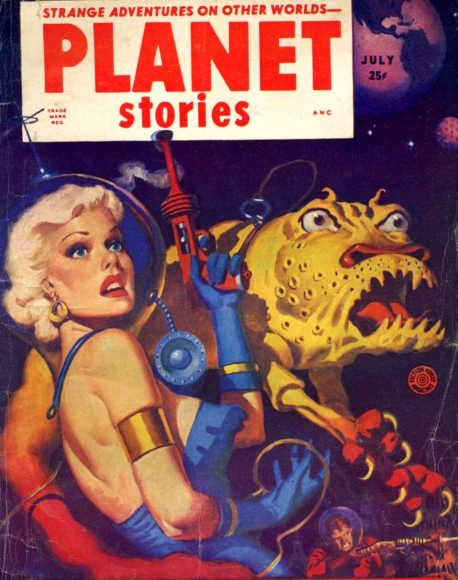

Planet Stories, with its notoriously lurid covers, gives another vision of the future. Atomic Blondes have been around a lot longer than that current film in the theater. This artist isn’t imagining our real future, but the future of comic books and Star Wars.

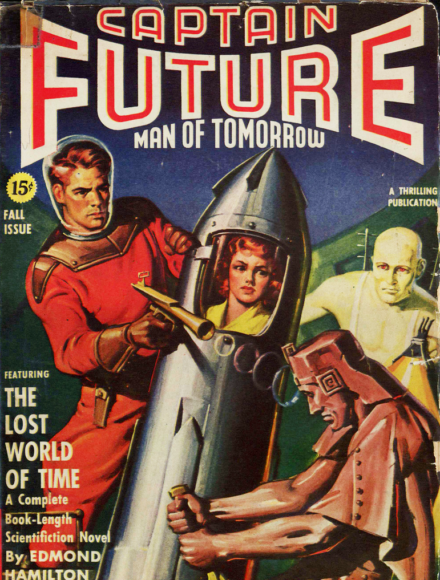

My friend Mike tells me the art in Planet Stories is corny now, but I think it captures a forgotten era. Take a look at “Galaxy Babes: The Gaudy, Brazen Cover Art Of Planet Stories” to get a better sense of its style. I get the feeling these covers convinced a good many adolescent boys in the 1940s to read science fiction. Another popular magazine was Captain Future because it had a similar artistic style on its covers.

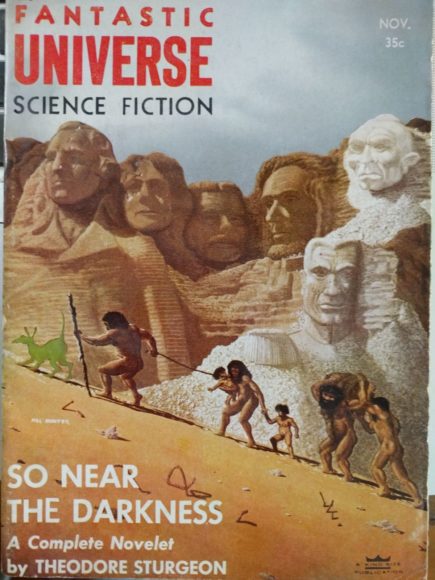

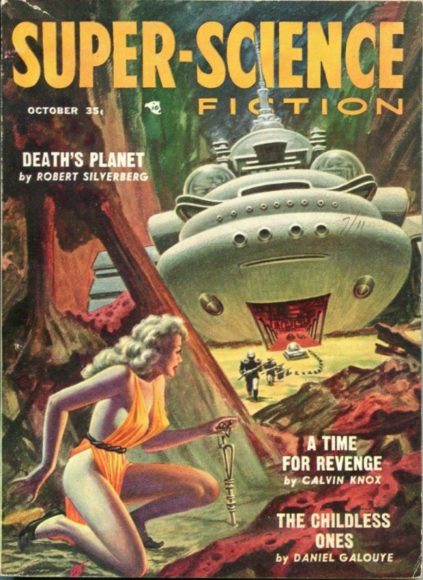

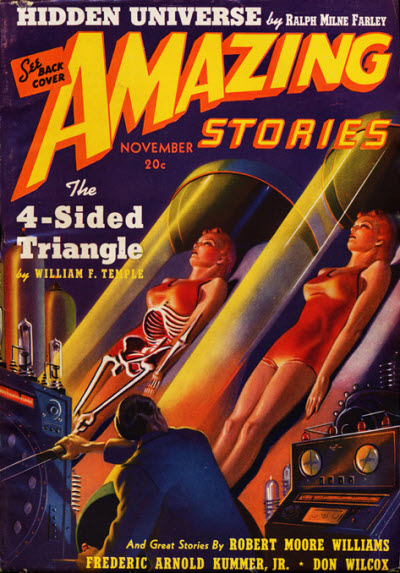

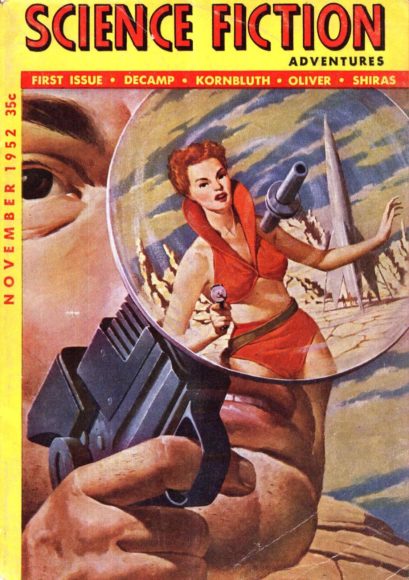

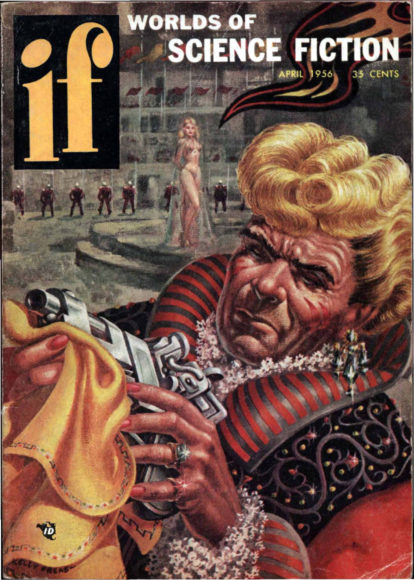

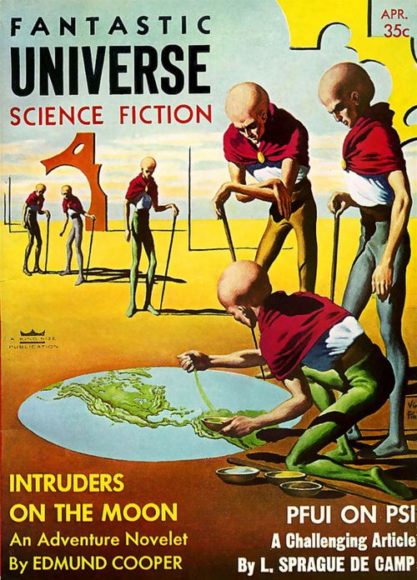

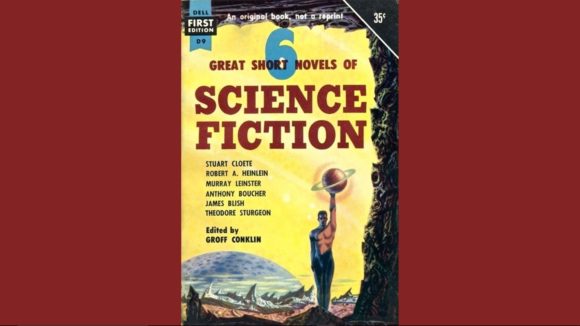

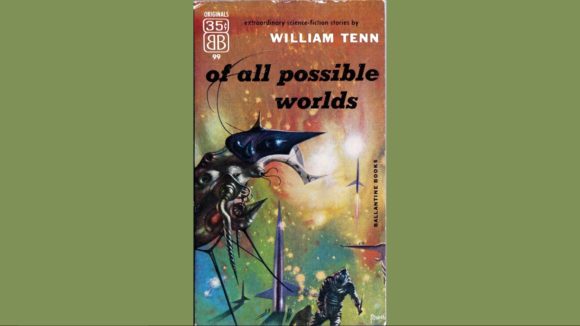

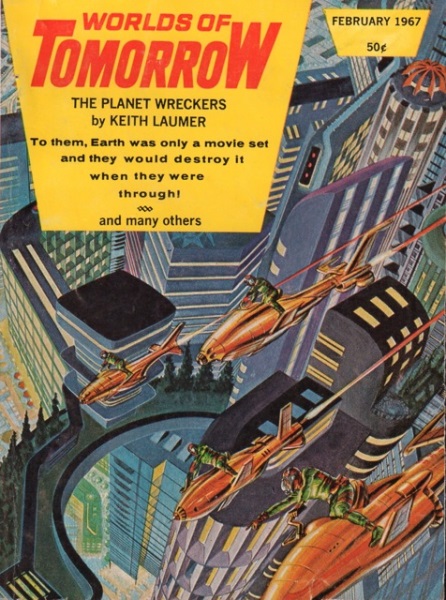

One thing I love about the old pulp art is the cover often told a story by itself. There are folks who collect 1950s paperback books because of their visually gripping covers and I think it’s for that same reason artists were so important to the pulps. I’m not sure people would collect them if they didn’t have the cover art they did. The illustrators captured a moment of action and it makes you want to buy the book/magazine to find out what happens next. Modern covers don’t do that. I wonder if 21st-century books and magazines would sell better if their covers showed in-the-moment action?

Just look at the covers below – don’t they make you want to read the stories?

JWH

Big Headed Humans With Telepathy

Our online science fiction book club is reading Before the Golden Age edited by Isaac Asimov and discussing one story a week. The first story is “The Man Who Evolved” by Edmond Hamilton, first appeared in the April 1931 issue of Wonder Stories. The story is very old fashioned, about a mad scientist, Dr. John Pollard, inviting two friends to observe an experiment. The narrator, Arthur Wright, describes what he and Hugh Dutton see when Pollard subjects himself to distilled cosmic rays.

Our online science fiction book club is reading Before the Golden Age edited by Isaac Asimov and discussing one story a week. The first story is “The Man Who Evolved” by Edmond Hamilton, first appeared in the April 1931 issue of Wonder Stories. The story is very old fashioned, about a mad scientist, Dr. John Pollard, inviting two friends to observe an experiment. The narrator, Arthur Wright, describes what he and Hugh Dutton see when Pollard subjects himself to distilled cosmic rays.

Wikipedia has a nice summary. You can read the story online in a scan of April 1931 Wonder Stories. Also, here’s a “Retro Review” that’s rather nice.

The setting is like something out of Frankenstein. Pollard has built a machine that gathers cosmic rays, which he believes is the agent of evolution. Each 15-minute exposure will alter his body as if had evolved for 50 million years. Wright and Dutton watch Pollard transform six times, each time his brain grows larger and his body becomes smaller. Pollard acquires telepathy and vast knowledge. Of course, all this is ridiculously unscientific. However, Hamilton is using the story to imagine what will happen to humans in the future. Hamilton is mining the same motherload as Olaf Stapledon, H. G. Wells, and many other early science fiction writers when they thought about the future of our species.

I love reading old science fiction stories like this because they give perspective on the nature of science fiction. You must ask yourself when you read such a tale, “What other science fiction stories have explored the same theme?” Right off the bat I thought of The Time Machine by H. G. Wells, First and Last Men by Olaf Stapledon, Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke, and Darwin’s Radio by Greg Bear – and of course “The Sixth Finger” from the old TV show, The Outer Limits, which featured a plot that Hamilton should have sued them over.

I love reading old science fiction stories like this because they give perspective on the nature of science fiction. You must ask yourself when you read such a tale, “What other science fiction stories have explored the same theme?” Right off the bat I thought of The Time Machine by H. G. Wells, First and Last Men by Olaf Stapledon, Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke, and Darwin’s Radio by Greg Bear – and of course “The Sixth Finger” from the old TV show, The Outer Limits, which featured a plot that Hamilton should have sued them over.

What all these stories boil down to is this: What will Humans 2.0 be like? Time and time again science fiction predicts people with ESP abilities. 1950s science fiction was full of such stories. And quite often, they predicted people with larger heads. Star Trek often featured many big headed aliens – the first pilot which became the episode “The Menagerie” featured big-headed aliens with telepathy.

I don’t think humans will ever evolve to have ESP powers. But we will create a species of intelligent machines that will have telepathy with radio waves and networking.

I am rather bothered by the constant desire to see humans have telepathy, telekinesis, clairvoyance, precognition and other wild talents. Aren’t they the same talents we assigned in the past to God and gods – prayer, the invisible hand of God, and prophecy? The reason why this country is so politically divided today is most citizens reject science for magic. They can’t accept evolution or global warming because it means giving up on an immortal soul and heaven.

Why can’t science fiction imagine evolution creating non-magical abilities for us? I consider science fiction failing if all it can come up with for our future evolution is reprocessed abilities from myths and religions. The insights of The Enlightenment are evolutionary. Compassion is evolutionary. Technology is evolutionary. Global cooperation is evolutionary. Computers and networking are evolutionary.

What natural abilities could we expect for biological evolution to give us in the future? I think the epitome of gifts would be a better understanding of reality without the desire for magic. If you watch the nightly news what we need is better bullshit detectors rather than telepathy. Personally, I’d like a better memory or a body that’s less prone to disease and decay. I wish I could synthesize more information and model bigger concepts in my head. I admit that telepathy could be useful, but I just can’t see any way that nature would give us built in radios. However, I can imagine us becoming more empathetic. Could that lead to being able to read each other’s moods or feelings?

One lesson I’ve learned from writing is my thoughts are not very coherent. It takes a lot of writing and editing to make them gel into something understandable. I’m not sure telepathy would be very effective. Writing takes work and time, and even then, it’s very hard to make a coherent message that others will read and interpret in the same way it was intended.

One lesson I’ve learned from writing is my thoughts are not very coherent. It takes a lot of writing and editing to make them gel into something understandable. I’m not sure telepathy would be very effective. Writing takes work and time, and even then, it’s very hard to make a coherent message that others will read and interpret in the same way it was intended.

Let’s say you are Edmond Hamilton in 1931 and want to convey the ideas of “The Man Who Evolved” to friends. Would telepathy have worked better than Wonder Stories?

I think science fiction needs to get out of the rut of big headed humans with ESP.

What’s Your Science Fiction Fantasy?

Have you ever wanted to write a science fiction novel? Do you picture yourself as the hero? Be honest – do you have what it takes to be a great protagonist? And just what kind of adventure would you want to have?

Novels, unlike real life, and especially for science fiction, can be about anything. But let’s get really far out. Let’s imagine you have died, and you regain consciousness. You’re in an empty room with another being. Let’s not be so pedestrian as to call it God. Let’s just say it’s a very advanced being with great powers. The being tells you how reincarnation works. You can now be sent anywhere in the multiverse to live again. Just pick. The multiverse is so infinite anything you can imagine exists somewhere. Just think what you want. Or you can volunteer to be randomly placed.

Do you have a favorite book or movie you’d like to live? Have you been refining a personal fantasy for years you want to try out? Think hard and long, because like a Genie with three wishes, your decision can come back to bite you in the ass. Do you want to stay on Earth, or venture out into the solar system, or beyond? Do you want to be rich? Have lots of sex? Travel far and wide? Invent wonderful machines? Do great deeds? Be a great leader? Spend a lifetime being compassionate?

Think about your favorite novels. Good ones usually involve much adversity and danger. Have you ever read Replay by Ken Grimwood? Jeff Winston, the novel’s protagonist dies at 43 and wakes up back in 1963, in his 18-year-old body to live his life again. He remembers his first life, so he tries to make his second life better. It doesn’t work out like he plans. (Do plans ever work out like planned?) Jeff dies again and gets yet another chance. Thus the title. This 1986 novel came out well before Groundhog Day in 1993. This is one of my favorite fantasies.

When I was younger, I would have picked being a colonist on Mars. Either like Heinlein’s Red Planet or Robinson’s Red Mars. Or maybe a person using suspended animation to see the future like Heinlein’s The Door Into Summer. Of course, having a time machine like the traveler in H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine would be fantastic. I can’t think of anything more rewarding than going up and down the timeline of Earth to see what happens in both the past and the future.

However, I’d still pick the Ken Grimwood type of adventure. I’d like to reincarnate into my 12-year-old self and try this life again, starting in 1963. (Strange that Grimwood and I both picked 1963.) That was the year my family moved from Miami to South Carolina. I’ve always wondered if I could have convinced my folks to let me stay with my grandmother instead. She lived alone and managed an apartment building for old people. I even met a woman there who had been on the Titanic. My grandmother could have used the help, and I could have made a much better life knowing what I know now – if I had tried harder. It would be rewarding to live another life doing everything differently.

Hinduism invented the idea of reincarnation to improve the soul. It’s a rather elegant idea once you think about it. Especially, if you could reincarnate into your own life for a second try. It’s taken me almost seven decades to figure out how things work. Would knowing what I know now at puberty make much of a difference? It would be fascinating to find out.

Science fiction is really a literature of imagining alternate lives using all of time and space. Most of the time we explore wishes gone bad. I think that’s why I’ve always loved the twelve Heinlein juvenile novels the most of any science fiction stories. Those stories published from 1947-1958 had a lot of bad things happen to the characters, but the sense-of-wonder adventures made up for any of the sufferings.

If you have the time, leave a comment about the choice you’d make.

Are You Nostalgic for Old SF Art?

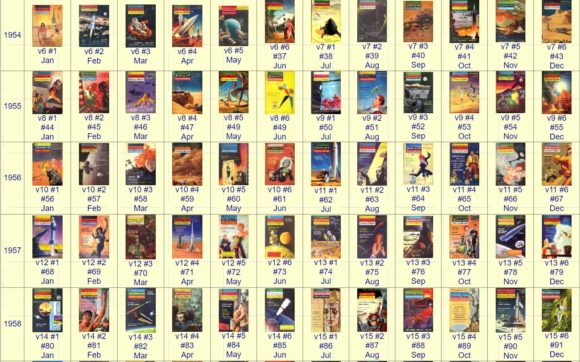

I recently joined two groups on Facebook devoted to science fiction art: Raypunk and Space Opera Pulp. It makes me wonder: How many people love science fiction art? Over the years I’ve encountered a number of blogs devoted to SF art like Joachim Boaz’s Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations and 70s Sci-Fi Art. And more databases of covers from science fiction magazines are showing up, like The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction from Phil Stephensen-Payne’s giant website. Even the Internet Science Fiction Database has become much more cover oriented. If you search Pinterest for “science fiction art” you’ll get countless collections.

Raypunk features more modern SF artwork but does include some older stuff. Space Opera Pulp is exactly what it says, and more to my nostalgic tastes. I would love to include samples of art these sites provide but I’m not sure about the rules of copyright violations.

It would be a wonderful blogging project to show the evolution of science fiction art as it parallels written science fiction. But I’m not sure how when it comes to getting permissions to use artwork. For now, I’m showing screenshots to these sites as a colorful enticement to try them. Here are some of the covers from F&SF. If you go to the site and click on a thumbnail it will show the large view. However, if you love a particular cover search for it on Google using the image view. Often larger higher resolution images are available.

For my personal use, I just right-click on images, select “Save image as…” and then put them into my SF Art folder. I search for the best scan at the highest resolution, and use my computer’s desktop background as an art gallery, using John’s Background Switcher to change images. It’s available for free and works on Windows and Mac. For Linux, I use Variety Wallpaper Changer. These programs automatically switch desktop background images at set time intervals. Here’s what my current desktop looks like:

One idea for a visual essay would be to take a single topic, say Mars, and show how fiction and illustrations have changed over time. Go year-by-year describing stories, quoting them, and showing the illustrations. Of course, that’s just another project to put on my pile of projects-to-do, but it would be fun. If anyone knows about the copyright laws that would apply to such a project, leave a comment, please.

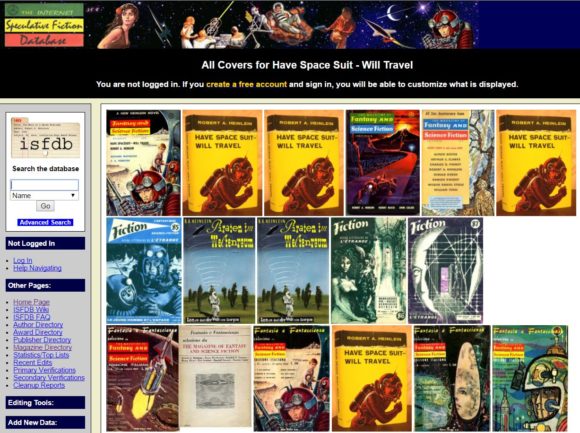

Another project would be to pick one artist, say Richard Powers, and show how their work changed with the science fiction times. ISFDB makes that easy. They list books by cover artist. I assume showing whole book covers are kosher when it comes to copyright.

That should allow a project showing all the covers for a particular book. Here’s the ISFDB page for Have Space Suit-Will Travel. It goes on and on.

But really, how many fans of SF art are out there? Is it in the hundreds, the thousands? I can’t imagine it in the tens of thousands, but maybe. Wouldn’t it be funny to find out if 167 people keep all those SF art websites going? I think they must come in two kinds. The folks that love the current work, and the folks that are nostalgic like me.

I think that because I believe that’s how people read science fiction. When you’re young you read new science fiction to imagine the future. When you’re old you read the old science fiction you loved when young and think about the past.

Here’s the desktop image as I finished this essay.

Cuteness in Science Fiction

I recently reread Little Fuzzy by H. Beam Piper and realized it’s success was probably due to cuteness. Cuteness is hard to define but generally deals with little creatures like kittens, puppies, babies, and toddlers. In the case of science fiction, cuteness comes in the form of little aliens or small robots.

Little Fuzzy was a read for my science fiction book club and most of the members enjoyed a story about cute critters being discovered by a gem miner on a distant planet. Piper’s plot examined what makes a being sentient, which is a serious, non-cute subject. However, because of the enduring popularity of fuzzy stories, we could also say Piper explored the concept of cuteness in science fiction. If you want to know more about the series read “The Fuzzy Story.”

I always pictured fuzzies sort of like Gizmo from Gremlins. Big eyes, small, furry – all the elements of cuteness. Big eyes seem to be a major element of anime. And, furry leads to furry fandom. I wonder if furries were inspired by Piper’s fuzzies? I’m not a fan of anime or furry so I’m not sure how they emerged, but I have to assume some form of cuteness was at the heart of their inspiration. Science fiction has always appealed to the young, and young at heart, so such subgenres of cute F&SF have their fans. I’m not one, but I do see cuteness as a hook for writers.

John Scalzi wrote a remake called Fuzzy Nation that has sales-appeal because of the cuteness of fuzzies.

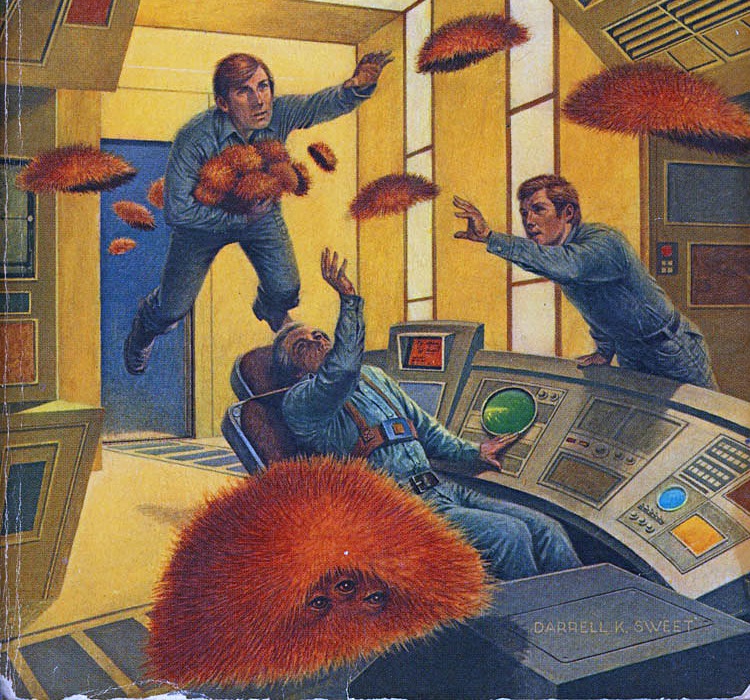

Science fiction is seldom about cute – but when science fiction does get cute, those stories are often fondly remembered. Just think of “Trouble with Tribbles,” David Gerrold’s classic Star Trek episode. Of course, I thought Tribbles were a rip off of Flat Cats from The Rolling Stones by Robert A. Heinlein, which had its cuteness appeal. And I have to assume the idea of cute critters that multiply quickly wasn’t original with Heinlein. One of the flat cats was named Fuzzy Britches. So fuzzies might have also come from flat cats.

Science fiction is seldom about cute – but when science fiction does get cute, those stories are often fondly remembered. Just think of “Trouble with Tribbles,” David Gerrold’s classic Star Trek episode. Of course, I thought Tribbles were a rip off of Flat Cats from The Rolling Stones by Robert A. Heinlein, which had its cuteness appeal. And I have to assume the idea of cute critters that multiply quickly wasn’t original with Heinlein. One of the flat cats was named Fuzzy Britches. So fuzzies might have also come from flat cats.

Cuteness is often linked to humor, like a cousin to comic relief. If the fuzzies hadn’t been cute, would Piper’s story had been as successful? Some stories can be improved with a dash of cuteness, but too much can be cloying. Most of the humor in “Trouble With Tribbles” seems strained today. It was saved by the cuteness of tribbles. I tend to think the cute fuzzies saved Piper’s story. It was reasonably well written for its time and market but it wasn’t that original. Piper was a solid genre writer back then, but isn’t well remembered today, except for creating fuzzies.

Pixar and Disney depend on a certain amount of cuteness to drive their genre and non-genre films. If there’s too much cuteness their stories will only appeal to children. Blockbuster animated films depend on attracting audiences of all ages.

My first encounter with cuteness in science fiction came from Willis, the Martian “bouncer” in Heinlein’s Red Planet. Willis was fuzzy and round like a medicine ball. Willis could protrude eye stalks or other appendages. He whistled. Which reminds me of R2D2. That’s another area of cuteness in science fiction, small robots like R2D2, WALL-E, and the little robots in Silent Running, Huey, Dewey, and Louie (for those people who remember really old science fiction).

My first encounter with cuteness in science fiction came from Willis, the Martian “bouncer” in Heinlein’s Red Planet. Willis was fuzzy and round like a medicine ball. Willis could protrude eye stalks or other appendages. He whistled. Which reminds me of R2D2. That’s another area of cuteness in science fiction, small robots like R2D2, WALL-E, and the little robots in Silent Running, Huey, Dewey, and Louie (for those people who remember really old science fiction).

So cute isn’t always fuzzy, it can be metallic, if small. The Heinlein juveniles had a number of strange alien creatures, but most of them were not cute. Often, cuteness in science fiction is repackaged puppies and kittens, reshaped, with a bit of mischievous intelligence. Hardly original, but it does tap into our fondness for cuteness.

One of the ironic aspects of Little Fuzzy was the main characters wanted to prove fuzzies were sentient, yet they also wanted to own them, treating them like pets. In some science fiction stories, humans have been pets to advanced aliens and we think that evil. Why is it okay when we do it?

One of the ironic aspects of Little Fuzzy was the main characters wanted to prove fuzzies were sentient, yet they also wanted to own them, treating them like pets. In some science fiction stories, humans have been pets to advanced aliens and we think that evil. Why is it okay when we do it?

Cute brings out our maternal and paternal instincts, which is a driving force in the pet industry. However, we’ve cruelly enslaved many species that aren’t suited to domestication. I haven’t read the sequels to Little Fuzzy, but I have to wonder if Piper explored fuzzy exploitation. Cuteness isn’t a great trait for many animals because we’ll cage them for our idle moments when we feel the need to be amused by something small and cute. We also tend to want our kids not to grow up and leave their cute stage, which is unfair. And doesn’t anime and furry fandom encourage arrested development?

We might not see a lot of cuteness in science fiction because it’s something we should limit. Our reality isn’t cute. Maybe I’m an old curmudgeon because I thought the best parts of Little Fuzzy were its serious aspects, and the cute aspects were misguided. Shouldn’t the humans have left the fuzzies alone, and just observed them? Shouldn’t the Prime Directive apply to cute critters too?

Is Oasis Science Fiction?

Amazon has rolled out a pilot for a new science fiction series called Oasis, based on the novel The Book of Strange New Things by Michel Faber. Unfortunately, I have not read the novel. The novel’s description barely sounds like what unfolded in the pilot. Readers compare the book to A Case of Conscience or A Canticle for Leibowitz, while I thought of Solaris while watching the TV show. Because we’ve only seen the 59-minute pilot, there’s no telling where the show will go, but I hope it incorporates more of the book – The Book of Strange New Things sounds fascinating.

As I watched the pilot, I felt I was seeing a series of iconic science fiction tropes that should appeal to the average science fiction fan looking for a new science fiction show. The only thing, the story didn’t feel very science fictional – at least not so far, and not to me. Peter Leigh (Richard Madden) is a pastor/chaplain whose wife has died and he’s mysteriously invited to travel to another planet because they claim to desperately need his skills. Peter arrives at the colony world only to find a miserable outpost where people suffer from menacing hallucinations. Three have died already. In the book, the preacher goes to another planet to teach the natives about Christianity. Now that could still happen in the television series, but the pilot didn’t introduce any native inhabitants on the colony world. It seems quite barren.

I ask, “Where’s the science fiction,” because of the nature of the story. It feels like a mystery. Why is a pastor needed to solve what might be a psychological or medical problem? Why are the people hallucinating? The same plot could be set on Earth today. Of course, this might reflect my jaded feelings toward science fiction. Spaceships and colony worlds don’t equal science fiction to me anymore. Conflicts built around off-world corporate shenanigans or galactic palace intrigue no longer means science fiction to me. I need something more.

All too often stories are called science fiction because of their costumes, sets, and scenery. A single-action .45 makes a western, a 9mm Glock makes a thriller, and a ray-gun makes a science fiction story if the plot is only about good guys vs. bad guys. That’s not good enough for me. I need science speculation in my science fiction.

Arrival had its audience thinking about communicating with aliens and how difficult that could be. I’d call that science fiction. The Martian and Gravity both dealt with problems unique to space exploration. Even Passengers which was nearly all Sci-Fi set redeemed itself with a uniquely ethical problem that would only come about because of long space missions using suspended animation.

So far Oasis seems completely cliché to me. I do hope it goes into production and explores new science fiction territory. The pilot had the feel of too many other science fiction series, but it hints at potential. The appearance of humans working in space is starting to develop a mundane sameness, which is a problem for many new SF shows. That’s why I loved the visuals of Gattaca – it made the future look different.

I fell in love with science fiction because of its ability to imagine things never imagined. Too often current science fiction works from templates. Every genre has to worry about running its tropes into the ground. And if you live long enough, it appears every genre does that.

I fell in love with science fiction because of its ability to imagine things never imagined. Too often current science fiction works from templates. Every genre has to worry about running its tropes into the ground. And if you live long enough, it appears every genre does that.

Of course, getting older is my problem. The young people who create and consume science fiction today probably won’t see what I’m talking about. At least not until they get older. I still crave new science fiction. It’s hard for me to find it when everything new looks old. For example, I admire Humans. But even its ideas are old. Still, I love Humans for presenting ideas about robots, AI, and consciousness in a fresh way.

Oasis did not seem fresh to me, or even science fictional, but that could change. The trouble is, I compare all first episodes to the first episode of Breaking Bad, which is a ridiculously high standard. All my favorite series have had a gang-buster of a first episode. That has me worried about Oasis, but I’m trying to stay positive. I think I’ll go read The Book of Strange New Things while waiting to see if Oasis gets the green light.

A Distance Too Far

In Beyond Earth: Our Path to a New Home in the Planets, Charles Wohlforth and Amanda R. Hendrix propose colonizing Titan, the largest moon of Saturn, and the second largest moon in the solar system. They reject constructing colonies on Mars and the Moon, claiming Titan offers the most resources for creating a permanent human settlement.

In Beyond Earth: Our Path to a New Home in the Planets, Charles Wohlforth and Amanda R. Hendrix propose colonizing Titan, the largest moon of Saturn, and the second largest moon in the solar system. They reject constructing colonies on Mars and the Moon, claiming Titan offers the most resources for creating a permanent human settlement.

Even though I don’t buy their premise, Wohlforth and Hendrix have written a book that nicely sums up the current knowledge on human space travel. What’s damning and depressing is their long litany of obstacles we face living in space. Over the years I’ve read news reports about the various dangerous health effects of space travel, but reading them all in one place makes me wonder if science fiction is completely wrong about the future of humans in space.

Oddly enough, near the beginning of their story, Wohlforth and Hendrix report books on space colonization are never taken seriously by professionals in the space industry. Evidently, such wild ideas are a danger to the careers of real space scientists. Wohlforth and Hendrix say books about colonizing space give amateur space enthusiasts hope, but those folks lie on the fringe, closer to science fiction fans than scientists. I’m a space enthusiast and a science fiction fan, so Beyond Earth is my kind of book, but I couldn’t help taking this news as a slight.

Between what W&H report on the dangers of space travel and the politics of the space industry, it feels like they have damned their own hopes in Beyond Earth to oblivion. The upside of their story is the reporting on private space programs, like SpaceX. That news is very encouraging, if not inspirational.

However, I have a problem with colonizing Titan. It’s a distance too far. Earth’s moon is three days away, Mars is six months. Titan is seven years! Wohlforth and Hendrix do make a case for faster space travel, but even if Titan was only hours away, it’s still too far, too cold, too strange, and, too inhuman. Science fiction hasn’t prepared us for living on Titan like it has for the Moon and Mars.

For the past fifty years, I’ve heard many arguments for colonizing the Moon or Mars. The whites and the reds, you might say. We know those worlds well enough to feel they aren’t so strange. They are barren, not fit for man nor beast, but we have already psychologically imagined ourselves there nonetheless. Titan is too far in distance and conceptualization.

From all the medical studies that Wohlforth and Hendrix review, I’m not sure humans are meant to live in space at all. Maybe our science fictional dreams are flat-out impractical. No matter what hurdle Wohlforth and Hendrix report, they don’t get discouraged, always coming up with hopeful workarounds. I was discouraged. Is it time for science fiction to start speculating about futures where humans never leave Earth? When do we give up? I’m not ready yet, but I do believe we need to start contemplating the possibility.

From all the medical studies that Wohlforth and Hendrix review, I’m not sure humans are meant to live in space at all. Maybe our science fictional dreams are flat-out impractical. No matter what hurdle Wohlforth and Hendrix report, they don’t get discouraged, always coming up with hopeful workarounds. I was discouraged. Is it time for science fiction to start speculating about futures where humans never leave Earth? When do we give up? I’m not ready yet, but I do believe we need to start contemplating the possibility.

After reading Beyond Earth I believe we should put all our manned space efforts into building bases on the Moon. We need to test humans living in low gravity for years. We’ve already discovered that living in microgravity for longer than six months causes permanent bodily damage. We’re learning that living in space will eventually cause permanent brain damage from galactic radiation. The safe time limit might be just 1-2 years, and there’s no practical shielding for spacecraft.

We should send robots to the Moon to construct an underground city safe from radiation. Those robots need to mine all the resources on the Moon that’s possible, so we fly the least weight from Earth. Robots should then fill the underground city with plants and test animals. When the robots have created a sustaining livable habitat, then send humans to stay for several years. Only then will we know what happens to our bodies living in less than 1 G. After we’ve gained knowledge from such an experiment, then we’ll know if we should travel greater distances. If we survive living on the Moon, then go to Mars or even Titan.

We should send robots to the Moon to construct an underground city safe from radiation. Those robots need to mine all the resources on the Moon that’s possible, so we fly the least weight from Earth. Robots should then fill the underground city with plants and test animals. When the robots have created a sustaining livable habitat, then send humans to stay for several years. Only then will we know what happens to our bodies living in less than 1 G. After we’ve gained knowledge from such an experiment, then we’ll know if we should travel greater distances. If we survive living on the Moon, then go to Mars or even Titan.

Wohlforth and Hendrix make a great case that we’re intentionally ignoring medical evidence. That we don’t want to believe that space is ultimately unhealthy. That our gung-ho nature makes us believe we can either use technology to overcome obstacles, or we can push our bodies further than the evidence suggests. I wonder if such optimism is just a way of fooling ourselves because we don’t want our science fictional dreams to come to an end.

I don’t know about you, but Titan is too far for me. What if Mars and the Moon are too far too? As Beyond Earth progresses it becomes more like science fiction than science fact. Anyone who writes science fiction might want to mine it for ideas. On the other hand, this book’s optimism makes me question the optimism of science fiction. Should we expect the future to give us everything we imagine?

Recommended Reading

When Did You Discover Time Travel?

How old were you when you first encountered the concept of time travel? I used to believe it was when I first saw the George Pal version of The Time Machine which came out in 1960, and I didn’t see until 1962 or 1963 when I was ten or eleven. Memory is a highly unreliable resource, especially for dating. I vaguely remember that seeing the movie made me get the book from my school library the next day. What’s weird, is I don’t remember being blown away by the idea of a time machine at that time. And time travel is certainly a concept that was mind blowing. What I remember, was being blown away at the idea that humans could mutate into new species. Now that was something to think about.

How old were you when you first encountered the concept of time travel? I used to believe it was when I first saw the George Pal version of The Time Machine which came out in 1960, and I didn’t see until 1962 or 1963 when I was ten or eleven. Memory is a highly unreliable resource, especially for dating. I vaguely remember that seeing the movie made me get the book from my school library the next day. What’s weird, is I don’t remember being blown away by the idea of a time machine at that time. And time travel is certainly a concept that was mind blowing. What I remember, was being blown away at the idea that humans could mutate into new species. Now that was something to think about.

My guess is I already knew about time travel. But when did I first encounter the idea?

In past decades I assumed all the great science fiction concepts like aliens, robots, time travel, interstellar travel, artificial intelligence came from reading science fiction. But in more recent years, as I wrote about my past, struggling to get the facts right, I realized that assumption was wrong. This line of thought started when I tried to remember when I first learned about dinosaurs. I wondered why little kids love dinosaurs, and if they understood dinosaurs existed millions of years ago and are now extinct. Those are heavy concepts too – vast times and extinction. I remember having dreams about dinosaurs when I was four or five, well before I could read, or attend school. And I don’t remember my parents telling me about dinosaurs. How did I learn about them?

Finally, I assumed I was introduced to all the far out ideas of science fiction via television, even though I grew up in the 1950s when television was primitive. That’s why I’ve felt I’ve always known about outer space, robots and traveling through time. Hell, I might have been exposed to time travel before I could tell time.

Evidently, childhood was a phase when my mind was a mass of proto-concepts gathered from television – like Pangaea before splitting into distinguishable continents. Reading science fiction shaped those vague impressions into precise concepts. Although reading Time Travel by James Gleick made me realize that time travel is a tremendously complex subject that we continue to refine.

Now here’s the thing I really want to talk about. In this age of alternate facts, should we be raising kids by stuffing them with fantasy and fantastic beliefs before they understand the nature of reality? We believe that make-believe is perfect for young minds, but is that true? Can you imagine a different way, where we taught kids facts first, and then later introduced them to fantasy?

Can you imagine growing up only seeing science shows that carefully explained what we know and how we know it? How would that change society? Would a fact-based early childhood education make us more realistic about reality? Is fiction the driving force that makes us constantly reshape reality with alternative facts? Does fantasy consumption encourage fantasy viewpoints? What an idea for a science fiction/fantasy novel! Imagine our world without science fiction and fantasy.

Let’s consider one more thing. What if we raised kids without fiction — at what age would they invent time travel on their own? When would they imagine building robots that could think like people, or traveling to Mars? Do we cheat our kids by telling them about all the far out ideas before they could invent them on their own?

Science fiction is a technology for transmitting speculative ideas, ones that writers have predigested for us, sort of like when Neo in The Matrix is taught martial arts with a program injected into his brain. I’m just wondering if we’d have more grit if we acquired our concepts through working out ideas ourselves.

Recommended Recent Reads:

- The Making of Future Man – James Gleick writes about Hugo Gernsback

- 30 years of Culture: what are the top five Iain M Banks novels?

- Disunion: Vision of Our Fragmented Future – Paul Di Filippo

- Beware the Retrofuture: Elan Mastai and Jack Womack Navigate the Problems of SciFi Nostalgia

- Groundhog Day Breaks the Rules of Every Genre

Science Fiction–Old and New

At The Little Red Reviewer, they are having Vintage Science Fiction Month where readers post reviews of older science fiction books they’ve recently read. I read The Stars Are Ours! and it’s sequel Star Born by Andre Norton, and The Drowned World by J. G. Ballard. I reviewed the process at my blog. But since then I’ve been thinking about why we read vintage science fiction, and if the why changes because of our age. Does someone who is twelve today, perceive The Stars Are Ours! different than I did when I was twelve in 1963?

At The Little Red Reviewer, they are having Vintage Science Fiction Month where readers post reviews of older science fiction books they’ve recently read. I read The Stars Are Ours! and it’s sequel Star Born by Andre Norton, and The Drowned World by J. G. Ballard. I reviewed the process at my blog. But since then I’ve been thinking about why we read vintage science fiction, and if the why changes because of our age. Does someone who is twelve today, perceive The Stars Are Ours! different than I did when I was twelve in 1963?

I assume the main appeal of vintage science fiction is nostalgia, and most of us who read it are older. In other words, we’ve lived long enough for some books to age. Do they age like fine wine or a stack of old newspapers? What is the essence of vintage?

That we notice a difference implies books written in the 1950s are different from books written in the 2010s. From my perspective, that’s true. Science fiction written in the 1920s has a distinctive style than science fiction written in any of the decades since. For proof of my point, check out The Pulp Magazine Archive. This site has scans of pulp magazines that you can read online, including early issues of Amazing Stories. I’m going to assume you’ll agree with me that the stories change. Now the question: Do we change?

If I could send a copy of The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu back to my teenage self to read and write a review, how would it be different from the review I would write today? Even President Obama was impressed with this book. Do all of us experience the same wow or is that impact different if the reader is young or old? Or if readers back in the 1960s could read The Three-Body Problem would they perceive it as something very different? Could they sense that it was written in the future like my younger self could sense reading The Skylark of Space by E. E. Smith was very old, written in the past?

Maybe another way to approach my query is to ask: Does an older reader today feel The Drowned World is vintage science fiction in the same way a young reader would? Our feeling of “vintage” might be a sense of nostalgia, while a young person might define it as feeling old-fashioned and quaint. But what if the young reader hadn’t read much science fiction? Would an unsophisticated 12-year-old reader of 2017 be that different from one in 1967? It could be possible they’d react to the story in many of the same ways.

When I first read Foundation by Isaac Asimov in the 1960s, I was reading stories written in the 1940s, and it didn’t seem old or vintage. Could a kid today get an ebook copy of Star Flight by Andre Norton that reprints The Stars Are Ours! and Star Born, not noticed the 1954 and 1957 copyright dates, read these books and think they were written today? Or would they sense their vintage quality?

Why Do You Love the Science Fiction You Love?

Science fiction has always been more than adventure stories for me. Science fiction is my Aristotle and Augustine, giving meaning to our meaningless reality. When you recall the science fiction tales that meant the most to you, were they thrill rides? Or maps of speculation? I use science to statistically explain how reality works, but I use science fiction to speculate how we can manipulate reality. That was when I was young. Now that I’m older, I use science fiction to imagine how things might play out on Earth after I leave.

Science fiction has always been more than adventure stories for me. Science fiction is my Aristotle and Augustine, giving meaning to our meaningless reality. When you recall the science fiction tales that meant the most to you, were they thrill rides? Or maps of speculation? I use science to statistically explain how reality works, but I use science fiction to speculate how we can manipulate reality. That was when I was young. Now that I’m older, I use science fiction to imagine how things might play out on Earth after I leave.

I’ve often wondered why science fiction is my chosen literature. Why do we pick the things we love? Is it free will, or some kind of adaptation or instinct? If a super-AI studied my habits like human scientists study chimps, what would it make of my choices in literature? Do aspects of my personality explain why I was drawn to science fiction?

Over at the Classic Science Fiction book club, we’ve been discussing our personal top ten favorite science fiction stories. What surprised me was the diversity of titles we embraced. Many of the stories are not on my Classics of Science Fiction, a list of the statistically most remembered science fiction books. You can see what stories members picked listed here. This made me wonder why we love the science fiction stories we do. The picks are as individualistic as fingerprints. There’s been some discussion at the group about all of this, but it inspired me to write this essay. Are we attracted to objectively great books, or do we seek books that mirror our subjective selves?

Sometimes I feel there’s no such thing as a great book, at least not in a measurable sense. The books we think are great are merely the ones that reflect our strongest desires. They don’t need to be well written, brilliant, or literary. They just need to trigger emotions. With me it might be accidental that they are science fiction. Or, are science fiction fans the kind of people drawn to the fantastic? Is mundane reality too tame for our ordinary lives?

Here are the ten titles I sent the book club. The list might be different on another day, or maybe not. These are the books I reread. These are the books I keep writing about. (Title links in the list go to WWEnd pages, title links in the essay are to older essays.)

- Have Space Suit-Will Travel by Robert A. Heinlein (1958)

- “The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany (1967)

- Tunnel in the Sky by Robert A. Heinlein (1955)

- Earth Abides by George R. Stewart (1949)

- Time for the Stars by Robert A. Heinlein (1956)

- Empire Star by Samuel R. Delany (1966)

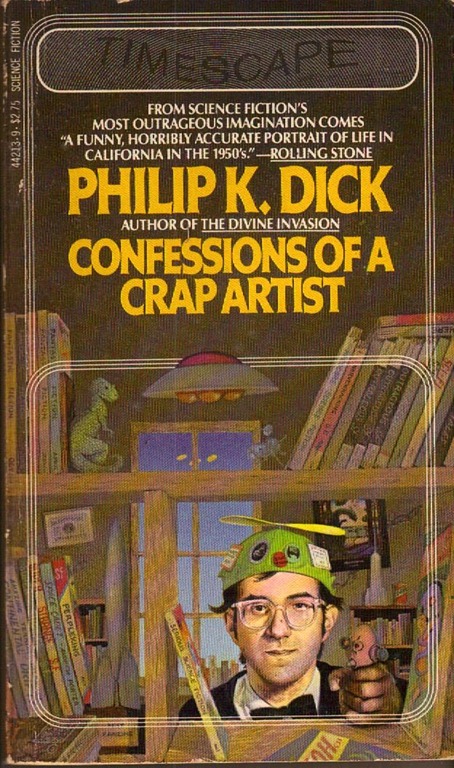

- Confessions of a Crap Artist by Philip K. Dick (1959)

- The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick (1962)

- The Time Machine by H. G. Wells (1895)

- The Door Into Summer by Robert A. Heinlein (1957)

My favorite science fiction is 50 years or older, and written by men. Is this list a Rorschach test for my personality? I do love modern science fiction, and often think it better written and more sophisticated than my favorites here. And I do prefer the diversity of modern SF. Yet, these are the stories burned in my memory. I read most of these stories before I turned 20. It might be our life-time favorites are the books we read in youth. First impressions are often the lasting impressions.

I first read Have Space Suit-Will Travel during the 1964-65 school year, at the dawn of Project Gemini. I was in the 8th grade and dying to blast off into space – just like Kip, the main character. I wished I was like Kip in many ways, but I wasn’t. I wanted to work hard in school, have my own science workshop, and live in a stable happy family located in a small town. None of those were true for me. I’ve read Have Space Suit-Will Travel six or eight times. It is the definitive science fiction novel for me. Back then it was my road map of the future, now it’s the tintype of my nostalgic past. For some baby boomers growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, the Heinlein juveniles were our substitute for religion. Those twelve books gave us faith, not in a sacred heaven, but in a secular outer space.

I first read Have Space Suit-Will Travel during the 1964-65 school year, at the dawn of Project Gemini. I was in the 8th grade and dying to blast off into space – just like Kip, the main character. I wished I was like Kip in many ways, but I wasn’t. I wanted to work hard in school, have my own science workshop, and live in a stable happy family located in a small town. None of those were true for me. I’ve read Have Space Suit-Will Travel six or eight times. It is the definitive science fiction novel for me. Back then it was my road map of the future, now it’s the tintype of my nostalgic past. For some baby boomers growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, the Heinlein juveniles were our substitute for religion. Those twelve books gave us faith, not in a sacred heaven, but in a secular outer space.

“The Star Pit” is also about the relentless desire to go into space, but ultimately deals with the limitations that hold us back. I first read this story in 1968, when I was slightly older and knew I wasn’t going into space. “The Star Pit” is tattooed on my heart, and whenever I reread it, the story squeezes tears out of my eyes, like beautiful songs of heartbreak. It might be the most mature of the ten stories I list here, even though it was written by the youngest writer at the time. The main character and my father were alcoholics who always had the restless urge to run away. I was Ratlit, and I wished my father had been the older Vyme. This story could easily have been a mainstream literary work without science fictional elements. I imagine its based on Delany’s own experiences, and he knew he wasn’t going into space too.

“The Star Pit” is also about the relentless desire to go into space, but ultimately deals with the limitations that hold us back. I first read this story in 1968, when I was slightly older and knew I wasn’t going into space. “The Star Pit” is tattooed on my heart, and whenever I reread it, the story squeezes tears out of my eyes, like beautiful songs of heartbreak. It might be the most mature of the ten stories I list here, even though it was written by the youngest writer at the time. The main character and my father were alcoholics who always had the restless urge to run away. I was Ratlit, and I wished my father had been the older Vyme. This story could easily have been a mainstream literary work without science fictional elements. I imagine its based on Delany’s own experiences, and he knew he wasn’t going into space too.

I read Tunnel in the Sky and Time for the Stars during the same school year as Have Space Suit-Will Travel. Both were about boys who left their families to be on their own. My parents’ marriage was a train wreck, and I wished I could have divorced them. I grew up loving stranded on deserted island stories, and Tunnel was a science fiction version of one. I believe the reason I was so attracted to the Heinlein juveniles is because their teen heroes always found ways to leave their parents.

Earth Abides also belongs to one of my favorite kinds of stories – last man on Earth stories. There is a side of me that wishes I was the last man on Earth. I love the idea of starting civilization over with a few other people or even being the last person watching nature reclaim the planet. I’ve always been kind of a loner even though I’ve been married for 38 years and have many friends. My childhood would have crushed most children, but I survived by dreaming, especially science fiction dreams.

Earth Abides also belongs to one of my favorite kinds of stories – last man on Earth stories. There is a side of me that wishes I was the last man on Earth. I love the idea of starting civilization over with a few other people or even being the last person watching nature reclaim the planet. I’ve always been kind of a loner even though I’ve been married for 38 years and have many friends. My childhood would have crushed most children, but I survived by dreaming, especially science fiction dreams.

Empire Star fits me philosophically. I read it maybe in 1967. Delany was closer to my age, and his work felt radically different from all the older science fiction writers I was discovering. Heinlein was like a father figure, but Delany was like a brother. Empire Star has wise advice for young people going out on their own for the first time. Delany’s insight into simplex, complex and multiplex was the best concept I ever learned from science fiction. I completely identified with both Comet Jo and Ni Ty.

I love Confessions of a Crap Artist because it’s how I remember the 1950s. My uncles were crap artists. I think all science fiction fans have a bit of crap artist in them. I love this novel because it shows we’re all crazy in unique ways. I believe this is PKD’s best book. Confessions is somewhat autobiographical, and one of Dick’s attempts to write literary. I love The Man in the High Castle because it’s about a little guy trying to survive in a very strange reality and make sense of it. How universal is that? PKD was great at writing about powerless people. His wife at the time he wrote these novels, Anne R. Dick, has written a memoir of those years, The Search for Philip K. Dick. To become a Dickhead means falling down the rabbit hole of trying to decipher PKD. I keep rereading his literary novels and his biographies to figure out why he wrote all those bizarrely wonderful novels that resonate with me.

I love Confessions of a Crap Artist because it’s how I remember the 1950s. My uncles were crap artists. I think all science fiction fans have a bit of crap artist in them. I love this novel because it shows we’re all crazy in unique ways. I believe this is PKD’s best book. Confessions is somewhat autobiographical, and one of Dick’s attempts to write literary. I love The Man in the High Castle because it’s about a little guy trying to survive in a very strange reality and make sense of it. How universal is that? PKD was great at writing about powerless people. His wife at the time he wrote these novels, Anne R. Dick, has written a memoir of those years, The Search for Philip K. Dick. To become a Dickhead means falling down the rabbit hole of trying to decipher PKD. I keep rereading his literary novels and his biographies to figure out why he wrote all those bizarrely wonderful novels that resonate with me.

I love The Time Machine because I consider it the archetype of science fiction. The time machine was cool, but not the point. Wells’ speculative explorations were epic. That’s how I define science fiction – as speculation. I love The Time Machine in the same way I love Olaf Stapledon’s majestic speculations. This is what I want from science fiction – to think really big thoughts.

I fell in love with The Door into Summer for two reasons. First, it’s about inventing robots in a home workshop. I always wanted to build robots. Second, Daniel Boone Davis slept his way into the future, and I would love to do that. I wish I could take 50-year naps to see how history progresses.

There are many other science fiction books I love, but for the moment, these are the ten I picked to share with the book club members. Picking ten books is just something fun we did this week, but I think our choices are revealing. Certainly more telling than exchanging astrological signs, maybe with as much validity as a Briggs-Myers test.

If you want to be revealing, list the ten science fiction stories you love most in the comments below.

Full Details

Full Details