Falling Off the Classics of Science Fiction List

We’ve recently updated the Classics of Science Fiction list from version 3 to 4. Because of this, some books that were on version 3 have fallen off the latest list. My main reason for producing the classics list is to track how books are remembered and forgotten. Most books are forgotten soon after they are printed, so to get on our list and stay on it for years means a huge number of readers are remembering those books. When books fall of the list, it doesn’t mean those books are unworthy of reading anymore, but that readers are forgetting them. Sometimes books are rediscovered, especially if they get new editions, produced as audio books, or made into films or television shows. Generally, books slide into obscurity. Old readers die off, and new readers never find the better older books.

We’ve recently updated the Classics of Science Fiction list from version 3 to 4. Because of this, some books that were on version 3 have fallen off the latest list. My main reason for producing the classics list is to track how books are remembered and forgotten. Most books are forgotten soon after they are printed, so to get on our list and stay on it for years means a huge number of readers are remembering those books. When books fall of the list, it doesn’t mean those books are unworthy of reading anymore, but that readers are forgetting them. Sometimes books are rediscovered, especially if they get new editions, produced as audio books, or made into films or television shows. Generally, books slide into obscurity. Old readers die off, and new readers never find the better older books.

Many of the titles that dropped off the list were books published before 1950. For version 3, we used several lists for library collection development, or critical histories of science fiction. For version 4, we had more fan polls. Version 3 had many short stories collections and anthologies that didn’t make it to version 4. Plus, many classic titles from 1950-1975 fell off. I assume newer readers aren’t discovering older books.

I also think version 4 is a better list than version 3. Most of the second half of version 3 didn’t make it to version 4. Which makes me wonder if the bottom half of version 4 will disappear when we create version 5 in ten years.

Here are the titles that fell of the list this time. The ones in red are books I’ve reread in the recent years and think still deserve to be read. There are plenty of books on the list below I still plan to reread.

- 334 (1972) by Thomas Disch

- The Absolute at Large (1927) by Karel Čapek

- Across the Zodiac (1880) by Percy Greg

- Again, Dangerous Visions (1972) edited by Harlan Ellison

- Animal Farm (1945) by George Orwell

- Astounding Science Fiction Anthology (1952) edited by John W. Campbell

- Back to Methuselah (1921) by George Bernard Shaw

- The Battle of Dorking (1871) by Sir George Chesney

- Before the Golden Age (1974) edited by Isaac Asimov

- Behold the Man (1969) by Michael Moorcock

- The Best of C. L. Moore (1975) by C. L. Moore

- The Best of C. M. Kornbluth by C. M. Kornbluth

- The Best of Henry Kuttner (1975) by Henry Kuttner

- The Best of Science Fiction (1946) edited by Groff Conklin

- Beyond Apollo (1972) by Barry N. Malzberg

- The Big Time (1961) by Fritz Leiber

- The Black Cloud (1957) by Fred Hoyle

- Brain Wave (1954) by Poul Anderson

- Bring the Jubilee (1953) by Ward Moore

- Bug Jack Barron (1969) by Norman Spinrad

- Casey Agonistes (1973) by Richard McKenna

- Chronopolis and Other Stories (1971) by J. G. Ballard

- The Chrysalids (1955) by John Wyndham

- The Clockwork Man (1923) by E. V. Odle

- The Coming Race (1871) by Edward Bulwer Lytton

- Dark Universe (1961) by Daniel F. Galouye

- Davy (1964) by Edgar Pangborn

- The Death of Grass (1956) by John Christopher

- Deathbird Stories (1975) by Harlan Ellison

- Deathworld (1960) by Harry Harrison

- Deluge (1927) by S. Fowler Wright

- The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth and Other Stories (1971) by Roger Zelazny

- Dorsai (1976) by Gordon Dickson

- Downward to the Earth (1970) by Robert Silverberg

- The Dream Master (1966) by Roger Zelazny

- The Dying Earth (1950) by Jack Vance

- E Pluribus Unicorn (1953) by Theodore Sturgeon

- The Embedding (1973) by Ian Watson

- Engine Summer (1979) by John Crowley

- Erewhon (1872) by Samuel Butler

- Final Blackout (1948) L. Ron Hubbard

- The Girl in the Golden Atom (1922) by Ray Cummings

- Gray Lensman (1951) by E. E. “Doc” Smith

- Greybeard (1964) by Brian Aldiss

- Gulliver’s Travels (1726) by Jonathan Swift

- The Hampdenshire Wonder (1911) by J. D. Beresford

- Herland (1915) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- The Iron Dream (1972) by Norman Spinrad

- Islands in the Net (1988) by Bruce Sterling

- The Lensman Series (1948) by E. E. “Doc” Smith

- The Listeners (1972) by James Gunn

- The Long Tomorrow (1955) by Leigh Brackett

- Looking Backward (1880) by Edward Bellamy

- The Lost World (1912) by Arthur Conan Doyle

- The Lovers (1961) by Philip José Farmer

- The Machine Stops and Other Stories (1909) by E. M. Forster

- Make Room! Make Room! (1966) by Harry Harrison

- Man Plus (1976) by Frederik Pohl

- A Martian Odyssey and Other Science Fiction Tales (1975) by Stanley G. Weinbaum

- The Midwich Cuckoos (1957) by John Wyndham

- A Mirror for Observers (1954) by Edgar Pangborn

- Norstrillia (1975) by Cordwainer Smith

- Nova (1968) by Samuel R. Delany

- Of All Possible Worlds (1955) by William Tenn

- On the Beach (1957) by Nevil Shute

- On the Wings of Song (1979) by Thomas Disch

- The Past Through Tomorrow (1967) by Robert A. Heinlein

- Perelandra (1943) by C. S. Lewis

- The Persistence of Vision (1978) by John Varley

- Play Piano (1952) by Kurt Vonnegut

- The Poison Belt (1913) by Arthur Conan Doyle

- Riddley Walker (1980) by Russell Hoban

- The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume One (1970) edited by Robert Silverberg

- The Science Fiction of Edgar Allan Poe (1976) by Edgar Allan Poe

- The Science Fiction of Jack London (1975) by Jack London

- She (1886) by H. Rider Haggard

- The Sheep Look Up (1972) by John Brunner

- The Short Stories of H. G. Wells (1927) by H. G. Wells

- Sirius (1944) by Olaf Stapledon

- The Skylark of Space (1946) by E. E. “Doc” Smith

- Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) by Robert Lewis Stevenson

- That Hideous Strength (1945) by C. S. Lewis

- To-Morrow’s Yesterday (1932) by John Gloag

- Under Pressure (1956) by Frank Herbert

- Untouched by Human Hands (1954) by Robert Sheckley

- A Voyage to Arcturus (1920) by David Lindsay

- The Wanderer (1964) by Fritz Leiber

- War of the Newts (1936) by Karel Čapek

- The Weigher of Souls (1931) by Andrew Maurois

- Who Goes There? (1948) by John W. Campbell

- The Wind’s Twelve Quarters (1975) by Ursula K. Le Guin

- The Witches of Karres (1966) by James H. Schmitz

- Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) Marge Piercy

- The World Below (1930) by S. Fowler Wright

Editor’s note: WWEnd has recently updated our Classics of Science Fiction list from version 3 to match Jim and Michael’s new version 4.

Used Book Sellers – Please Put Your Barcodes on the Back Cover

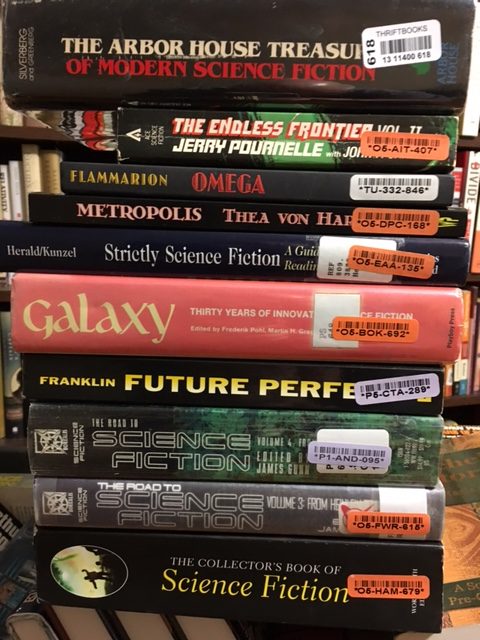

I buy lots of used books from ABEbooks.com and Amazon.com. And it appears that selling used books online is big business. And when businesses get big, they automate. Most of the used books I buy online now come with barcode stickers. I’m sure such automation is needed to keep prices down, and handling to a minimum. What I hate, though, is when they put the barcode sticker on the front of the book, or the spine.

Don’t they know that some of us are book collectors? Don’t they know that used book buyers love the cover art? I sometimes decide on buying the paperback or hardback by their cover art. And the best thing about science fiction paperback books from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s are their covers. I sometimes pass on a cheap ebook just to get an old paperback with a great cover.

It drives me nuts to get a book with a beautiful cover and a damn barcode sticker is right in the middle of the art.

Most of these barcode stickers aren’t easy to remove, or damage the cover when removing. It would be different if they peeled off easily leaving no mark. But that’s not the case.

And I can understand the urge to put the barcode on the spine of the book, because that makes shelving and finding books easier. But if the sticker doesn’t peel off, I have to look at them on my book shelves, and they’re ugly.

If you have to put a barcode sticker on a book, use the back cover. And don’t cover up the book’s original barcode. Goodreads users, as well as many other book database programs, use the ISBN barcode to scan in with a smartphone. When that barcode is covered, I have to type it in by hand.

I understand booksellers make their money by selling in volume. I don’t buy $300 first editions. When I buy from ABEbooks, which orders their default searches by lowest total cost, I’m getting an out-of-print book shipped to me from across the country for just a few dollars. So I can’t expect much. But the condition of the book, and its cover is important to me.

Some of these books are fifty years old, and their cover art takes me back to my childhood. They are a dwindling resource, and damaging them reduces their collector value.

SF v. Fantasy (1999 v. 2016)

I’m researching fan polls for favorite science fiction books for v. 4 of the Classics of Science Fiction list, and I came across something curious. In the “THE INTERNET TOP 100 SF/FANTASY LIST” there seems to be greater love for fantasy in 1999 than in the 2016 Goodreads poll “Best Science Fiction & Fantasy Books.” Both polls involved thousands of voters, which is a good sample. Now I’m just looking at the top 100 books, so many of the popular fantasy titles from the Internet 100 list might show up further down on the Goodreads list. If you look at the second and third hundred books on Goodreads, fantasy starts appearing with greater frequency.

I’m researching fan polls for favorite science fiction books for v. 4 of the Classics of Science Fiction list, and I came across something curious. In the “THE INTERNET TOP 100 SF/FANTASY LIST” there seems to be greater love for fantasy in 1999 than in the 2016 Goodreads poll “Best Science Fiction & Fantasy Books.” Both polls involved thousands of voters, which is a good sample. Now I’m just looking at the top 100 books, so many of the popular fantasy titles from the Internet 100 list might show up further down on the Goodreads list. If you look at the second and third hundred books on Goodreads, fantasy starts appearing with greater frequency.

However, comparing just the most popular 100 books suggests that fantasy is less popular in 2016 than in 1999. Do you think that’s true? Both lists where voted on by people who like to use the internet. My hunch would be more males voted in 1999. Both systems allow for multiple ranked entries with the Internet 100 using 1-10 and Goodreads using 1-5. There’s no telling what the voter demographics are like for each. My guess is younger readers voted in the Internet 100, and Goodreads appeals to all ages. If that’s true, does that mean science fiction sticks with people as they get older?

Any other ideas?

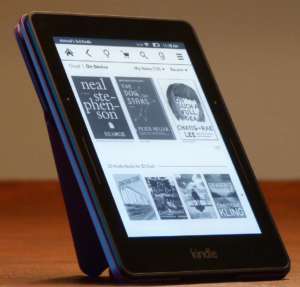

Buying Science Fiction: Paper or Digital?

At my blog, Auxiliary Memory, I’ve been adding Amazon Affiliate links to all the various lists of science fiction books I’ve created. This tedious activity is quite informative. The most obvious trend I spotted, is we’re moving away from mass market paperbacks. They still exist, but far fewer in number. How many people are buying them? Even more surprising is how often I see a mass market paperback cheaper than the Kindle edition. A common price is $7.99 for the ebook, and $7.19 for the mass market paperback. And if you’re an Amazon Prime customer, the price of shipping is built into the paper price. Are they encouraging people to keep buying paperbacks? Or, are ebook prices fixed, and Amazon is discounting the paper?

On the other hand, many classic science fiction novels are only available in Kindle editions, or Kindle and Audible editions, so the only choice is digital. And the prices for Kindle ebook editions are all over the map. Currently, you can get many of Greg Egan’s great novels from the 1990s for $2.99 each. But other books from that era go for $7.99, $9.99, $11.99 or even $13.99. I can’t believe they price older ebooks equal to cheaper trade paperback editions. But then, the prices for trade paperbacks are moving closer to what hardbacks were not many years ago, and the prices of hardbacks are soaring.

On the other hand, many classic science fiction novels are only available in Kindle editions, or Kindle and Audible editions, so the only choice is digital. And the prices for Kindle ebook editions are all over the map. Currently, you can get many of Greg Egan’s great novels from the 1990s for $2.99 each. But other books from that era go for $7.99, $9.99, $11.99 or even $13.99. I can’t believe they price older ebooks equal to cheaper trade paperback editions. But then, the prices for trade paperbacks are moving closer to what hardbacks were not many years ago, and the prices of hardbacks are soaring.

I found it quite disturbing how many books are only available in digital. My all-time favorite science fiction novel, Have Space Suit-Will Travel can only be bought in an ebook or audio editions. The Kindle is $6.99. Several of Heinlein’s books are only available in these formats. Does that mean fewer people are reading Heinlein? Or, do his fans prefer digital editions? I can understand the flood of forgotten novels from decades past having only Kindle editions. I doubt there are enough buyers to make a print edition break even. And ebooks have been wonderful for bringing back classic SF long out of print. Recently most of Clifford Simak’s novels and short stories showed up in new digital editions.

I tend to think pricing for ebooks is related to the fame of the book or author. Dune, a classic from the 1960s, goes for $9.99. The Diamond Age by Neil Stephenson, from the 1990s goes for $11.99. In the old days, age meant cheap paper editions. I remember buying pocket books costing 35 cents off of twirling wire racks when I was a kid. It’s hard to imagine children plunking down $10 for a Sci-Fi wonder today.

Since I’m adding Amazon Affiliate links I have to decide which is the edition people will most likely want. For the most part, I’ve settle on Kindle editions because they are often cheaper compared to trade paper editions, the common print format. If you consume science fiction versus collecting it, going digital is more thrifty. Digital also seems science fictional too, but I do know that many people still prefer to read off of paper. And I have to wonder how many people prefer spending $14.95 for a trade edition over $7.99 to read a Kindle edition?

I would love to know: how many people still collect science fiction in hardback?

I would love to know: how many people still collect science fiction in hardback?

Since I’m adding links to the Classics of Science Fiction list, I’m assuming most people are going through the list reading the classics, and not collecting. I’ve been building my own digital library of the Classics of Science Fiction list on the cheap. The Kindle Daily Deals, BookBub, Early Bird Books and LitFlash all send me daily reminders of ebook specials. I’ve bought dozens of books from the Classics of Science Fiction list for $1.99 each. I’m still kicking myself for not buying Jack Faust by Michael Swanwick and Blood Music by Greg Bear from yesterday’s deals. I saw the emails and thought, “I’ll do that in a minute,” and then forget. Damn. Today they are $6.15 and $7.99. Jack Faust has no paper edition, and Blood Music is $13.99 for the trade paper. Although you can get a used hardback copy for $0.01 and $3.99 shipping.

Most of my science fiction collection is digital now, either Kindle or Audible. I only buy paper if it’s much cheaper, the only available format, or I can’t get it from the library. In this regard, I know I’m atypical. I think most science fiction fans prefer to build large collections of visible books. Yet, is that practical with the rising cost of printed books?

I’ve committed to digital. All my Kindle and Audible books are available on my iPhone, which goes with me everywhere. That’s rather futuristic, because I’m carrying around a couple thousand books in my pocket. In the past, when I moved and loaded 2,000+ books in boxes into a truck, it was a huge pain in the lower back. It’s hard to believe I now carry that many books with me everywhere I go.

Literary Recognition for Science Fiction

Over the decades science fiction books have received little respect from the literary establishment. Most science fiction readers don’t give a damn either. Yet, in recent years I’m seeing signs of acceptance. I’m sure true fans of mimetic fiction still ignore our genre, but the larger society might be throwing us a few crumbs of admiration. Books that win the Pulitzer Prize tend to paint realistic portraits of complex characters. Science fiction has other goals, usually sculpting our hopes and fears about the future into an exciting story. That inherently makes science fiction a different art form compared to the literary novel. I wish the literati would recognize that the science fiction novel has its own aesthetics. But I also hope the average science fiction fan will understand what they are missing.

Over the decades science fiction books have received little respect from the literary establishment. Most science fiction readers don’t give a damn either. Yet, in recent years I’m seeing signs of acceptance. I’m sure true fans of mimetic fiction still ignore our genre, but the larger society might be throwing us a few crumbs of admiration. Books that win the Pulitzer Prize tend to paint realistic portraits of complex characters. Science fiction has other goals, usually sculpting our hopes and fears about the future into an exciting story. That inherently makes science fiction a different art form compared to the literary novel. I wish the literati would recognize that the science fiction novel has its own aesthetics. But I also hope the average science fiction fan will understand what they are missing.

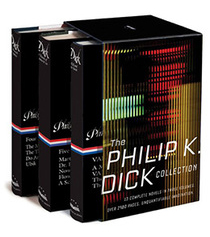

Back in 2007, when Library of America published its first collection of Philip K. Dick novels, it felt like science fiction was finally getting a nod from the big boys. Library of America describes itself: “Founded in 1979, the nonprofit organization was created with a unique and unprecedented goal: to curate and publish authoritative new editions of America’s best writing, including acknowledged classics, neglected masterpieces, and historically significant documents and texts.” Publishing Philip K. Dick with Edith Wharton, Walt Whitman, James Baldwin, Louisa May Alcott, Mark Twain, Raymond Chandler, Kate Chopin, William Faulkner, Herman Melville, seems like a literary endorsement. I wish Phil had lived to see his books in LOA editions. And I wish his literary novels had LOA editions.

Library of America has since published Ursula K. Le Guin and Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and even Edgar Rice Burroughs, and H. P. Lovecraft. In 2012, LOA produced American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in a two-volume set. Collectively, those novels portray an alternate literary view of the 1950s. This week I wrote, “Who Still Reads 1950s Science Fiction?” and thought I’d get damn few readers. It’s gotten over 700 shares on Facebook, and 1,600 views. That’s far from what a news story about Pokémon would get, but a lot for my little blog. What surprised me, was how many younger readers loved 1950s books. Sometimes great literature is defined by great writing, other times, as books that last. A handful of science fiction novels are showing signs of lasting.

Library of America has since published Ursula K. Le Guin and Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and even Edgar Rice Burroughs, and H. P. Lovecraft. In 2012, LOA produced American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in a two-volume set. Collectively, those novels portray an alternate literary view of the 1950s. This week I wrote, “Who Still Reads 1950s Science Fiction?” and thought I’d get damn few readers. It’s gotten over 700 shares on Facebook, and 1,600 views. That’s far from what a news story about Pokémon would get, but a lot for my little blog. What surprised me, was how many younger readers loved 1950s books. Sometimes great literature is defined by great writing, other times, as books that last. A handful of science fiction novels are showing signs of lasting.

Recently I noticed that Everyman’s Library has an edition of The Foundation Trilogy by Isaac Asimov, listed in their catalog under Contemporary Classics, along with A. S. Byatt, Albert Camus, Raymond Chandler, D. H. Lawrence, Thomas Mann, and other powerful wordsmiths. Everyman’s Library’s other SF titles includes, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood and Stories of Ray Bradbury by Ray Bradbury. Asimov and Bradbury were added to their collection in 2010, after Library of America had come out with their Philip K. Dick volumes. I don’t know if that was keeping up with the Joneses, or if Everyman’s Library discovered The Foundation Trilogy is the most remembered science fiction story from the 1950s.

These publishers are famous for their uniform volumes that look classy. Everyman’s Library editions are elegant hardbacks, with thin white pages and an attached ribbon bookmark, which remind me of bibles.

These publishers are famous for their uniform volumes that look classy. Everyman’s Library editions are elegant hardbacks, with thin white pages and an attached ribbon bookmark, which remind me of bibles.

I poked around Modern Library, the grandfather of classic reprints in uniform editions, but didn’t spot any science fiction. However, their famous (infamous) list of 100 Best Novels does include Brave New World, 1984, Slaughterhouse-Five, and A Clockwork Orange. My recent post, “The Classics of Science Fiction in 12 Lists” mentions six other lists from sites identifying general classics that include some science fiction.

What got me started on this literary recognition scavenger hunt was noticing that the New York Review Books Classics, a prestigious publisher of quality paperbacks for literary elite readers, had two books by John Wyndham, The Chrysalids and Chocky. Wyndham, the author of The Day of the Triffids, has always garnered a bit more respect than the average science fiction writer. But NYRB Classics also publishes a collection of short stories by Robert Sheckley. That surprised me! And they reprinted The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe by D. G. Compton. I had first read Compton when he appeared back in the 1960s in the first series of Ace Science Fiction Specials. I’ve wondered what had happened to him. Compton had become a forgotten writer. What a way to be remembered.

Vintage Books, another quality trade publisher, has a nice uniform collection of books by Samuel R. Delany. Vintage had published a uniform collection of Philip K. Dick. Now Mariner Books publishes PKD, also with uniform covers, that makes the collection appear literary. While many older science fiction writers get reprinted only in eBook editions, PKD is in print in paper, eBook and audio, and for almost everything he wrote, including his crappiest novels, and his weirdly philosophical ramblings.

Most classic science fiction novels are available on Audible.com, as audio book editions, and that’s a kind of recognition too. Unfortunately, many of those same classics have no print edition, just eBook editions. Some of Robert A. Heinlein’s famous novels currently have no book you can hold edition.

On the other hand, many of the greatest science fiction books of all time are remembered in deluxe editions, some bound in expensive leather, from publishers like The Easton Press, Franklin Books, and The Folio Society. This doesn’t mean these books are literary masterpieces by academic standards, but they are books so well loved that people will spend $$$ for enduring, beautiful, timeless, bindings.

Science fiction has finally been accepted by the Best American series. The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy is appearing for the second time in 2016. The series editor is John Joseph Adams, and the guest editor is Karen Joy Fowler. It’s not that the genre was lacking in annual best-of-the-year anthologies, but this one will be seen with the other Best American series in bookstores, and that’s a kind of endorsement for the genre too.

Science fiction has finally been accepted by the Best American series. The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy is appearing for the second time in 2016. The series editor is John Joseph Adams, and the guest editor is Karen Joy Fowler. It’s not that the genre was lacking in annual best-of-the-year anthologies, but this one will be seen with the other Best American series in bookstores, and that’s a kind of endorsement for the genre too.

Newspapers like The New York Times and The Guardian, that once shunned the genre, are now spending more time reviewing science fiction books. This might be due to the expanded space provided by the web, or it might be due to science fiction being popular with people who use technology.

Since the 1970s, science fiction has often been taught in schools and colleges, but usually in special courses. I’m not sure anyone can get a degree in science fiction, just yet, but science fiction has a growing history, and an expansive body of work. This year, The Great Courses offered How Great Science Fiction Works. I listened to it on Audible, and I’m now watching it on The Great Courses Plus on my Roku. Dr. Gary K. Wolfe gives an excellent overview of the genre in 24 lessons. The major books he discusses can be found pictured at SF Signal. Wolfe ties them all together by theme, revealing the evolution of our genre.

Before the 1950s, science fiction as a genre, was known to few people. I’ve been trying to remember the first time a science fiction book came up in a popular movie. In 1985, with Back to the Future, Marty McFly’s father, George, was a science fiction writer. But he was the butt of jokes. There’s been science fiction movies almost as long as there has been movies. But can you remember the first time a character in a movie talked about reading a science fiction book? I can’t. There’s a kind of literary recognition when a title is mentioned inside a work of pop culture. Sometimes it’s obvious, like all the books slipped into Lost. Other times it might be a minor set piece. If you pay attention, science fiction books do get mentioned more often now. Anyone want to claim the first time?

All of the above aren’t real examples of literary recognition. There’s no official stamp of literary approval. There’s even a reactionary movement against the concept of “classic” books. Too many “great” books are by dead white guys, that many feel are no longer meaningful to our times. Today, there’s a growing demand for books that are recent, relevant, and representative. Literary quality or reputation no longer matter. By the standard of popularity, then science fiction is getting tremendous recognition, and it’s showing more diversity. Even mainstream literary writers dabble with science fictional story elements.

All of the above aren’t real examples of literary recognition. There’s no official stamp of literary approval. There’s even a reactionary movement against the concept of “classic” books. Too many “great” books are by dead white guys, that many feel are no longer meaningful to our times. Today, there’s a growing demand for books that are recent, relevant, and representative. Literary quality or reputation no longer matter. By the standard of popularity, then science fiction is getting tremendous recognition, and it’s showing more diversity. Even mainstream literary writers dabble with science fictional story elements.

However, has science fiction ever come close to The House of Mirth, Their Eyes Were Watching God, On the Road, To Kill a Mockingbird, Invisible Man, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Bell Jar, or A Signature of All Things? Those are just the literary novels that came to mind in five seconds. Like I said, the goals of science fiction are different. But what if science fiction included literary aspects too? So far, I’m still not hearing any claims that’s happening.

Can Science Fiction Anticipate the Future of Gender?

Will the current concepts of male and female exist in the future? SF writer have no trouble seeing horrible futures, like The Handmaid’s Tale. So, can science fiction writers imagine desirable futures? Especially, when it comes to future gender roles? We’re seeing more stories like Too Like the Lightning, Ancillary Justice and Lock In where science fiction anticipates new views of gender. I just read The Disappearance by Philip Wylie, that rethought gender roles in 1951. Wylie wasn’t totally enlightened by today’s standards, but he saw women had far more abilities than society allowed. How much did Wylie get right? And how much can today’s SF writers get right about our future?

Is it possible for science fiction to imagine a gender equal society? Or, must we always examine the problem through dystopian failures? We assume we’re progressing towards more equality because of the changes we’ve already undergone. So how come we don’t see more positive futures in science fiction? Will we ever create a society based on individual equality? Ada Palmer explores such an idea in Too Like The Lightning.

I’m getting so tired of dystopian science fiction. I know novelists need conflict to forward their plots, but can’t they imagine conflict in a superior society that gives readers hope for the future? I want to believe in futures where killings like in Orlando never happen, and men like Jessica Valenti describes in Sex Object are as rare as dinosaurs. Can’t science fiction envision a tomorrow without all the things we hate about ourselves today? We don’t need unrealistic utopias or childlike fantasies, but more hope would be appreciated.

Do we assume since misogyny has always existed, it will always exist? I just read When Everything Changed by Gail Collins, that shows how the U.S. was dramatically transformed from 1960-2008 by women’s rights. Philip Wylie would have been gratified by Collins’ report.

The Disappearance tried to convince its readers to think different about women. Wylie anticipated attitudes that wouldn’t surface until the late 1960s. His novel is dated, yet feels relevant because our society still lacks equality. It seems tragic we can’t imagine better societies, but still have engaging conflicts for characters and readers. Star Trek might be one positive example, but was it?

The Disappearance tried to convince its readers to think different about women. Wylie anticipated attitudes that wouldn’t surface until the late 1960s. His novel is dated, yet feels relevant because our society still lacks equality. It seems tragic we can’t imagine better societies, but still have engaging conflicts for characters and readers. Star Trek might be one positive example, but was it?

We identified most gender issues long ago, but there’s some kind of barrier to solving all of them. We can ask why everyone in the 19th century didn’t see the evils of slavery. What will 22nd century people condemn us for not seeing that’s obvious to them but not us? Can science fiction writers be the new abolitionists? I’m not sure making more female characters into protagonists does the trick.

Wylie made conceptual leaps in 1951 that we’ve come to accept. Women now work at jobs that would have been unbelievable then. What will it take for us to think equally far out of the box? Most men today believe women can do anything they want, but they still see women as sex objects. Can science fiction imagine societies where humans have free will to escape their biological programming?

How many readers changed their attitudes about women by reading The Disappearance in 1951? If science fiction can imagine us solving our problems in the future, can reading it change us now?

The Disappearance uses a clever plot gimmick to explore gender issues and feminism. In the first chapter, at 4:04:52 p.m., all the women disappear from Earth, and the story begins describing how men live without women. In the second chapter, at 4:04:52 p.m., all the men disappear, beginning a second story sequence describing how the women live without men. Wylie anticipates many feminist issues that wouldn’t be recognize until decades later. He’s a tiny bit progressive with his views on homosexuality and race, but falls far short of what we know. Wylie was ahead of his time — but not all of him.

We can never know when science fiction is right about the future, but won’t contemplating more possibilities enlighten us?

Wylie gives us Dr. William Percival Gaunt, philosopher, writer, competent man (much like Heinlein’s Jubal Harshaw, but without being an ass). Gaunt becomes the central figure in the story about males. Gaunt’s home is near Coral Gables and Coconut Grove, Florida. I was born in 1951, and grew up in Coconut Grove and Coral Cables, so this novel was especially meaningful to me. In the other half of the twin plot, Paula Gaunt, Bill’s wife, is a competent woman who becomes the leader of a small group of women. Both of the Gaunts eventually travel to Washington to help decide the fate of the nation.

Like the novel The City & The City by China Miéville, the men and women occupy the same physical space without seeing each other, but their realities diverge, because the men and women react differently to the same event. Their worlds eventually become two very different places.

Modern SF writers like Ann Leckie and Ada Palmer explore the future of gender today. If their ideas become common in the future, will future readers consider their books classics? Because Wylie gets much wrong, I’m not sure The Disappearance is a classic. Wylie felt men wildly underestimated the potential of women, but ultimately theorizes it takes a male and a female to make a whole person. We, of course, would consider that silly today.

Modern SF writers like Ann Leckie and Ada Palmer explore the future of gender today. If their ideas become common in the future, will future readers consider their books classics? Because Wylie gets much wrong, I’m not sure The Disappearance is a classic. Wylie felt men wildly underestimated the potential of women, but ultimately theorizes it takes a male and a female to make a whole person. We, of course, would consider that silly today.

Wylie felt women could do they same jobs as men, had the same sexual drive as men, thought women had been falsely imprisoned by society’s expectations and roles, but he couldn’t imagine women being 100% independent. He thought men and women needed each other, and considered non-heterosexuals as misguided. Our modern view of gender and sexuality assumes everyone is equal and independent. We see gender and sexuality as important traits for identity, but differences that don’t cause inequality. We’re moving away from marriage as a bond between an unequal male and female, to a legal contract between equal individuals. But isn’t that just a start? Won’t gender roles in society be vastly altered by current trends? Can science fiction imagine those changes?

Wylie follows Plato by suggesting that man and woman are half-a-soul that make one gestalt soul. That’s where this novel idealistically fails, but I have to give Wylie tremendous credit for seeing things very differently from the 1951 normal. When Everything Changed was the perfect book to read after The Disappearance. Gail Collins’ book magnificently shows how much things have changed. I’m not sure Wylie could foresee his ideas playing out. Sex Object would have blown his mind, but not all of it.

There were 1970s feminists who advocated changes to society that would eliminate the ways we make women into sex objects. They were labeled radical, and the reaction against them helped generate a wave of anti-feminism, which also turned many against the ERA. Our society has become hypersexualized since then. Can science fiction writers imagine societies where we don’t objectify each other and still have healthy, rewarding sex lives? To many 1970s feminists we’ve gone backwards.

Any science fiction written today that shows how we outgrow gender might seem prophetic in the future if we eventually erase those traits. I think that’s what Ada Palmer is showing in her novel. Her characters claim “she” and “he” are outmoded concepts, but are sometimes used for the convenience of the 21st century reader to understand the 25th century. But the narrator explains that’s even deceptive for our primitive minds. Because sometimes the narrator will call someone a he, but only mean that person has male traits, but not necessarily male biology. As science fiction writers are discovering, getting rid of gender pronouns are difficult. Will any personality traits be considered masculine and feminine in the future? Does Palmer go far enough?

Do such science fictional speculations suggest future humans might also get rid of sex? Can we, or the science fiction writers of today, imagine future males and females with no unique gender roles? Or gender disappearing from language?

Sex Object, is a feminist memoir that beautifully illustrates the problem of sexual objectification. How could science fiction writers take the problems Valenti describes and create a fictionalized enlightened future that solves them? Valenti wants society to process out the repugnant aspects of seeing or being objects, but she doesn’t know how. Is that our future? Finding politically correct ways of pursuing sex and romance?

In the past, science fiction was mostly about traveling into space. Today, science fiction is often about staying home on Earth. We may even stop talking about men and women. Those labels might become essentially meaningless. Can writers create stories where readers comprehend gender equality? I just bought The Fate of Gender: Nature, Nurture, and the Human Future by Frank Browning. That makes me wonder what nonfiction books inspired Philip Wylie.

Do science fiction writers actually imagine new concepts, or do they observe them beginning in society, like the dots in the yin and yang symbols?

The Classics of Science Fiction in 12 Lists

If every science fiction fan voted for their favorite science fiction books, would the most popular books become the classics of science fiction? Is an academic stamp-of-approval required to validate a classic? Are classics simply the books that society fails to forget? Here are twelve sites that identify the best science fiction books. Six focus on science fiction, and I use their top ten books. Six focus on general literature, and I pull out all the science fiction they recognized.

The consistency of these results are amazing, but they also reflect a complete lack of diversity. Only eight women writers appear on these lists. If you follow the links to the full lists, you will see more women writers, and somewhat greater diversity. Worlds Without End appears to be the only site that actively seeks to discern the better newer books, which reveals that women and people of color are writing a great deal of good science fiction. But we have to recognize that the slow process of books gaining wide recognition means those books are often behind current liberal thinking. I expect in another 25-50 years, future lists using the same methods will reflect the best books being published today.

I also expect the most progressive readers in the future will consider some of our currently accepted beliefs shameful. One goal of science fiction is speculating on how future people will think, and those books written today that guess right will be declared classic and visionary. And those that guess wrong will be used as examples of how the past was politically incorrect.

And which books will be forgotten? Because over time, books that are deemed unforgettable, are forgotten. The first list, Classics of Science Fiction, is the oldest list, and its top two books aren’t remembered on the other eleven lists. Most of these books from these lists are 25-60 years old, and even though young readers vote in the polls, they grow up reading books written a generation or two before their time.

Still, it’s amazing to see how many of the old usual suspects show up time and again. It really does suggest that a few books out of every generation acquire the “classic” designation – at least for a while. I expect in a century, most of these titles, and even authors, will spark no recognition. But for now, it’s rather fascinating why and how they are cherished in our memories.

Classics of Science Fiction (meta-list based on 28 lists)

- The Demolished Man – Alfred Bester (25)

- More Than Human – Theodore Sturgeon (25)

- Dune – Frank Herbert (25)

- The Foundation Trilogy – Isaac Asimov (24)

- A Canticle for Leibowitz – Walter M. Miller, Jr. (24)

- Stand on Zanzibar – John Brunner (24)

- The Left Hand of Darkness – Ursula K. Le Guin (24)

- The Time Machine – H. G. Wells (23)

- The War of the Worlds – H. G. Wells (23)

- Childhood’s End – Arthur C. Clarke (23)

Worlds Without End Top Listed Book of All-Time (53 lists producing 9 meta-lists)

- The Dispossessed – Ursula K. Le Guin (13)

- The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood (13)

- Frankenstein – Mary Shelley (13)

- Dune – Frank Herbert (12)

- The Left Hand of Darkness – Ursula K. Le Guin (12)

- The Doomsday Book – Connie Wills (12)

- The Forever War – Joe Haldeman (11)

- Ender’s Game – Orson Scott Card (11)

- Flowers for Algernon – Daniel Keyes (11)

- Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – Philip K. Dick (11)

Listopia Best Science Fiction & Fantasy Books (ongoing poll at Goodreads, number of votes)

- Ender’s Game – Orson Scott Card (5,244)

- Dune – Frank Herbert (4,160)

- Nineteen Eighty-Four – George Orwell (3,238)

- Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury (2,358)

- Brave New World – Aldous Huxley (1,937)

- A Wrinkle in Time – Madeleine L’Engle (1,624)

- Foundation – Isaac Asimov (1,586)

- The Hunger Games – Suzanne Collins (1,454)

- The Giver – Lois Lowry (1,283)

- Slaughterhouse-Five – Kurt Vonnegut (1,283)

Listopia Best Science Fiction Books (ongoing poll at GoodReads, number of votes)

- Dune – Frank Herbert (804)

- Ender’s Game – Orson Scott Card (775)

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams (654)

- 1984 – George Orwell (552)

- Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury (428)

- Foundation – Isaac Asimov (393)

- Brave New World – Aldous Huxley (342)

- Hyperion – Dan Simmons (298)

- Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – Philip K. Dick (288)

- Stranger in a Strange Land – Robert A. Heinlein (257)

Top 100 Sci-Fi Books (ongoing poll at Sci-Fi Lists)

- Dune – Frank Herbert

- Ender’s Game – Orson Scott Card

- The Foundation Trilogy – Isaac Asimov

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams

- 1984 – George Orwell

- Stranger in a Strange Land – Robert A. Heinlein

- Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury

- 2001: A Space Odyssey – Arthur C. Clarke

- Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – Philip K. Dick

- Neuromancer – William Gibson

NPR Top 100 Science-Fiction, Fantasy Books (2011 fan poll, > 50,000 votes)

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams

- Ender’s Game – Orson Scott Card

- The Dune Chronicles – Frank Herbert

- 1984 – George Orwell

- Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury

- The Foundation Trilogy – Isaac Asimov

- Brave New World – Aldous Huxley

- Neuromancer – William Gibson

- I, Robot – Isaac Asimov

- Stranger in a Strange Land – Robert A. Heinlein

These lists cover all literature. I’m not limiting myself to the top ten, but listing any science fiction books that got recognized.

Modern Library List of 100 Best Novels (MLA)

- Brave New World – Aldous Huxley (#3)

- 1984 – George Orwell (#13)

- Slaughterhouse-Five (#18)

- A Clockwork Orange (#65)

100 Best Novels of the 20th Century (Radcliffe Publishing Course)

- 1984 – George Orwell (#9)

- Brave New World – Aldous Huxley (#16)

- Slaughterhouse-Five – Kurt Vonnegut (#29)

- A Clockwork Orange – Anthony Burgess (#49)

- Cat’s Cradle – Kurt Vonnegut (#66)

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams (#72)

- The War of the Worlds – H. G. Wells (#85)

The 150 Best English Language Novels of the 20th Century (compiled by librarians)

- Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury (#28)

- Stranger in a Strange Land – Robert A. Heinlein (#31)

- 2001: A Space Odyssey – Arthur C. Clarke (#66)

- Dune – Frank Herbert (#86)

The Best English Language Novels from 1923 to the Present (Time Magazine, alphabetical)

- 1984 – George Orwell

- A Clockwork Orange – Anthony Burgess

- Brave New World – Aldous Huxley

- Neuromancer – William Gibson

- Slaughterhouse-Five – Kurt Vonnegut

- Snowcrash – Neal Stephenson

- Ubik – Philip K. Dick

1,001 Books to Read Before You Die (Popular book, editor’s choice)

- Chocky – John Wyndham

- Cryptonomicon – Neal Stephenson

- Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – Philip K. Dick

- The Drowned World – J. G. Ballard

- Foundation – Isaac Asimov

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams

- I, Robot – Isaac Asimov

- Neuromancer – William Gibson

- Solaris – Stanislaw Lem

- Stranger in a Strange Land – Robert A. Heinlein

The Greatest Books (meta-list, 107 lists, all literature, just 17 SF books out of top 500)

- 1984 – George Orwell (#23)

- Brave New World – Aldous Huxley (#82)

- Slaughterhouse-Five – Kurt Vonnegut (#124)

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea – Jules Verne (#149)

- A Clockwork Orange – Anthony Burgess (#164)

- The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood (#189)

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams (#265)

- Dune – Frank Herbert (#270)

- Cloud Atlas – David Mitchell (#284)

- A Wrinkle in Time – Madeleine L’Engle (#295)

- Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury (#307)

- The Time Machine – H. G. Wells (#327)

- The Road – Cormac McCarthy (#366)

- The War of the Worlds – H. G. Wells (#378)

- Atlas Shrugged – Ayn Rand (#379)

- Neuromancer – William Gibson (#382)

- 2001: A Space Odyssey – Arthur C. Clarke (#411)

Update 6/29/16:

Just found a 13th list. The Library of Congress opened its 2016 version of “America Reads” exhibit June 16th, where the public voted for the books. See this explanation, “The books that have shaped American life.” Here are the SF books it includes – (order from the list):

- Slaughterhouse-Five – Kurt Vonnegut

- The Moon is a Harsh Mistress – Robert A. Heinlein

- A Wrinkle in Time – Madeleine L’Engle

- Dune – Frank Herbert

- Atlas Shrugged – Ayn Rand

- Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury

Interestingly, the 2012 exhibit, where the books were chosen by the curators, only three science fiction titles were selected, Atlas Shrugged, Fahrenheit 451 and Stranger in a Strange Land.

Do You Want To Go To Mars?

Back in 1964, when I first read Red Planet by Robert A. Heinlein, I decided my goal in life was to get to Mars. I was 12. When Mariner 4 whizzed by Mars taking crude images in July 1965, showing the red planet was more like the Moon than science fiction, I was disappointed, but I still wanted to go. I grew up with Projects Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. Sputnik flew the month after I started first grade, and Apollo 11 landed the month after I finished the twelfth grade. I assumed Americans would be on Mars before 1980, and colonization would start before I was too old to go. I don’t think I was alone having this dream. It was impossible for me to imagine in 1972 that humans would never leave Earth orbit for decades.

A warm day on Mars is what we’d call cold here on Earth, and a cold day on Mars is what we’d call hell. We’re now all afraid of getting too many X-rays, but living on Mars would cook our gonads in constant radiation. And only a geologist could admire the scenery of the fourth planet. So why do so many dream of going to Mars?

NASA just announced a series of posters advertising for jobs on Mars. There seems to be more excitement in the 2010s about Mars than anytime since the 1960s. Elon Musk has become the D. D. Harriman of Heinlein’s imagination, the man who is selling Mars. The Martian by Andy Weir and its movie version has inspired millions to daydream about adventures on Mars even though Mark Watney had one wretched experience after another. Like Dorothy in Oz, he just wanted to go home. Thousands of people applied to join Mars One, a proposed Martian colonization scheme that involves one-way trips. What is so alluring about Mars that some people are willing to give up everything?

NASA just announced a series of posters advertising for jobs on Mars. There seems to be more excitement in the 2010s about Mars than anytime since the 1960s. Elon Musk has become the D. D. Harriman of Heinlein’s imagination, the man who is selling Mars. The Martian by Andy Weir and its movie version has inspired millions to daydream about adventures on Mars even though Mark Watney had one wretched experience after another. Like Dorothy in Oz, he just wanted to go home. Thousands of people applied to join Mars One, a proposed Martian colonization scheme that involves one-way trips. What is so alluring about Mars that some people are willing to give up everything?

For those of us who dream of moving to Mars, have you ever analyzed why you want to go? Looking back to my twelve-year-old self, I have to say reading Heinlein was my first motivation, but is fiction really a good justification? And if I had known about the details of how the astronauts of Project Gemini ate and shat in space for two-weeks, I would have given up my ambition back then. If I’m honest with myself, I know I never had the Right Stuff.

I think all adolescents want to escape their situations, and mine included alcoholic parents who dragged my sister and I around the country in their own restless search for greener pastures. It’s no wonder I would have gladly gone all the way to Mars to find a life of my own. Science fiction was my escape, my positive therapy for what should have been a psychologically damaged childhood. Science fiction and rock & roll were my trip to Mars, converting an adolescence I should have suppressed to a time I nostalgically cherish.

When Red Mars by Kim Stanley Robinson came out in 1993, my Mars mania reignited. Then when The Case for Mars by Robert Zubrin showed up a few years later, with a very practical plan for getting to Mars, I got even more excited. By then I had given up any naïve dream of going to Mars myself, but I finally had hope again that humans would go. That was twenty years ago, and we’re still doing endless 90-minute laps around the home world.

I believe Elon Musk is an unrealistic optimistic about how to get to Mars, but I hope I’m wrong. I know the Mars One people are clueless, but I wish them well. There’s a practicality that comes with getting old. I’m glad the young aren’t infected. We need foolish people to do impossible things. But I’ve reached an age where I now question the value of going to Mars. I’m not sure space is suited for humans, but it is perfect for machines.

I believe Elon Musk is an unrealistic optimistic about how to get to Mars, but I hope I’m wrong. I know the Mars One people are clueless, but I wish them well. There’s a practicality that comes with getting old. I’m glad the young aren’t infected. We need foolish people to do impossible things. But I’ve reached an age where I now question the value of going to Mars. I’m not sure space is suited for humans, but it is perfect for machines.

And, if we do want to adapt humans to space, I think our starting place should be the Moon, not Mars. The Moon is three days away, and a perfect place to construct the self-sufficient industrial city to launch human space exploration of the solar system and beyond. If Homo sapiens can’t adapt to living on the Moon, going to Mars will be pointless. But if we can thrive on the Moon, Mars will be easy.

There’s one very important factor about those posters from NASA – they’re promoting jobs that involve long term stays. Going to Mars, or the Moon, can’t be about planting the flag. I didn’t understand the value of work as a kid. Space travel was a thrill. Living in space really means working in space. I just wanted to hop a rocket and escape into fictional fantasies. The people who truly want to live in space need twenty years of relentless preparation, and then will work 15-hour days on the final frontier. Pioneers don’t waste much time reading science fiction, playing video games, or enjoying VR.

Of course, such gritty self-evaluation makes me wonder about why I read science fiction. It’s still escapism. It’s now nostalgia. But it’s also a kind of hoping that humans will adapt to living in space. Where does that desire come from? Why is it important that our species go to Mars? Species have habitats. Why should we create new habitats for ourselves? Especially ones so tremendously ill-suited for our biology? What if fish wanted to live on land? Wait, some did.

Judith Merril’s Take On Classic Science Fiction

I have to thank Aqueduct Press (“Bringing Challenging Feminist Science Fiction to the Demanding Reader”) for publishing The Merril Theory of Lit’ry Criticism by Judith Merril. If you have sufficient years reading science fiction you’ll remember the annual SF collections of best short stories Judith Merril edited back in the 1950s and 1960s. What Ritch Calvin has done is collect all her introductions and summaries from those 1956-1969 annual anthologies, 38 book review columns from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (1965-1969), and a few additional essays from Extrapolation, a journal devoted to studying science fiction. For ebook readers, he also includes the introductions to all the short stories from all the anthologies. That’s 622 pages (ebook) or 360 pages (paperback) of commentary on science fiction, a goldmine of insight into old science fiction. Both editions are available from Amazon or the publisher, and hopefully your local bookstore.

I have to thank Aqueduct Press (“Bringing Challenging Feminist Science Fiction to the Demanding Reader”) for publishing The Merril Theory of Lit’ry Criticism by Judith Merril. If you have sufficient years reading science fiction you’ll remember the annual SF collections of best short stories Judith Merril edited back in the 1950s and 1960s. What Ritch Calvin has done is collect all her introductions and summaries from those 1956-1969 annual anthologies, 38 book review columns from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (1965-1969), and a few additional essays from Extrapolation, a journal devoted to studying science fiction. For ebook readers, he also includes the introductions to all the short stories from all the anthologies. That’s 622 pages (ebook) or 360 pages (paperback) of commentary on science fiction, a goldmine of insight into old science fiction. Both editions are available from Amazon or the publisher, and hopefully your local bookstore.

Judith Merril was an exceptionally well-read reviewer, not only referencing a detailed knowledge science fiction and its history, but literary works and science books. She was also pithy, funny and to the point. Here’s her 1965 review of PKD’s latest, where at the end of a previous book review had stated, “Philip Dick did it better three years ago, in The Man in the High Castle.” She then continues…

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Philip K. Dick, Doubleday, $4.95, 278 pp.

I don’t mean, this time, that his new book is similar in theme or treatment. Rather, that I wish it were more so, at least in characterizations and structure. Phil Dick is, one might say, the best writer s-f has produced, on every third Tuesday. In between times, he ranges wildly from unforgivable carelessness to craftsman-like high competence. In the case of Palmer Eldritch, I would guess he did his thinking on those odd Tuesdays, or rather on one of them, and the actual writing in every possible minute before another Good Tuesday came on him. Here is a riotous profusion of ideas, enough for a dozen novels, or one really good one; but the stuff is unsorted, frequently incompleted, seldom even clearly stated. The style is alternately dream-slow-surreal and fast-action-pulp. Thematically, he at least approaches, and sometimes stops to consider, virtually every current crucial issue: drug addiction, sexual mores, over-population, the economic structure of society, the nature of the religious experience, parapsychology, the evolution of man — you name it, you’ll find it. The book, with all this, is inevitably colorful, provocative, and (frustratingly) readable. I wish I thought it possible that Dick might some time go back to this one, publication notwithstanding, and finish writing it.

One reason why I immediately hit the buy button for The Merril Theory of Lit’ry Criticism is because I bought her anthologies a half-century ago, and started reading F&SF around that time too. For years now I’ve been meaning to order those anthologies used from ABEBooks, just so I could read the commentaries. To have Calvin throw in all the book reviews was too good to be true, but it is.

I’ve been hung up on my science fictional past, and this book is perfect for retracing steps I first took in 1965. Anyone who collects old SF from that era will find this volume to be a treasure chest of clues.

Merril, on occasion, had a lot to say about a book. She often read a book more than once to write a review. She was determined to understand science fiction at a level beyond what most readers ever try. Look at this review of Nova by Samuel R. Delany, one the more memorably SF books from the 1960s. I probably read this review at the time too. This is a great example of what Merril does when she goes long:

Leave your preconceptions behind, again, when you open Samuel Delany’s new Nova (Doubleday, $4.95). My own problem was the opposite of my friend’s with 2001: I came to this book with an anticipation keener than any I have brought to anything since — well, probably Vonnegut’s Rosewater — looking for (at least an approach to) the Great Novel I (still) expect from the author of Empire Star, Babel-17, The Einstein Intersection, “The Star-Pit,” “Aye and Gomorrah,” and (now) Nova: and what I got instead was a first-rate jim-dandy solid provocative science-fiction novel.

It took me a while to realize I had no honest cause for complaint — a while longer to discover I damn well did have cause — longer yet to understand (first) why I was so irritated, and (eventually) the real reasons to be annoyed with the book.

Delany is in an almost unique position in s-f today: everybody loves him. The “solid core,” the casual readers, the literary dippers-in, the “new thing” crowd — Delany is all things to all readers. It is an untenable position — unless, of course, he gets as good as I think he will eventually be. Swift, Melville, Carroll, Twain, Conrad are all read by children as well as litterateurs, their plots are reducible to comic book format, while their themes are subtle and complex enough to sustain reading after delighted analytical reading.

Well, Delany is not Swift or Conrad — yet; but his seven previous novels and scattered shorter works have already placed him out of the judging in the transient-writer class; and as the work of an apprentice-great, Nova must be regarded as more of a fascinating exercise than a satisfactory achievement. But —

What is wrong with the book is simply that the author tried to do — not too much, but enough: he tried to write a modern novel on all the levels required (by the same standards I am applying) of a contemporary work: if he did not quite succeed, it is well to remember that neither has anyone else — yet; and few other attempts have managed to stand up meanwhile as, at least, solid entertainment.

Here is what I wrote after my first reading of the book:

Nova is a deceptive book in several ways. Don’t let the first page stop you; the book is not — except superficially — a Planet Stories superficiality. And don’t rush in to identify with anyone too soon; it may take a while to decide whose viewpoint you are using.

The protagonist, the hero, and the viewpoint character are (in order of appearance, not necessarily identity) a 19-year-old gypsy-born spacehand-and-minstrel named the Mouse; a cosmically wealthy and powerful space captain named Lorq Von Ray; and a wandering scholar and spacehand called Katin.

The book is intriguingly, but unnecessarily, complex — mostly written underwater, as it were; that is, under the surface of a (too) familiar space adventure plot, as warm and sparkling with the strange and rich biota of Delany’s inner world.

There is, for instance, the Mouse’s “sensory-syrynx,” an instrument which can produce a complete multi-media show — visual, musical, and olfactory display; a recurrent theme involving Tarot lore; a carefully constructed cultural context in which the 20th century serves as the classical period of a culture 1000 years older, whose technological and philosophic beginnings are rooted in the transitions of today. There are the Illyrion furnaces which have made whole planets habitable and space traversable, great glowing pits called Hell here, and Gold there — and tiny battery power packs primed by micrograms of the same stuff, which run the wondrous syrynx and Katin’s tiny recorder. There is a gorgeous physiological/astrophysical/political philosophic construct in parallels; and a sweep of action from Athens to the Pleiades, with fiery fights, drinking bouts, mosques and museums, diver-hunters and cyborg-spacemen — and with all this, the book is somehow lacking. I do not know what it lacks; perhaps if it had come after Empire Star and Babel-17, and before The Einstein Intersection, I should have found no lack, at all. But, just as I went on from the first banal page, simply because it was Delany, and I could be sure of finding the richness and excitement I did find, so I went on from history lesson to battle scene to gorgeous syrynx session to Tarot lore, hoping I could be equally sure of learning why they were all there together. I think an explanation was given to me in the last pages — and I do not think it satisfied me. But never mind: the fans will love it.

That was the first time around; I have now read the book — to be precise — two and a half times (the third time, only those passages marked the second time for re-examination), and when I started to retype that earlier comment, I thought the word unnecessarily must have been a typographical error. Alas, not so: the error was not mechanical, but (doubly) human — the reader’s and writer’s both.

There is nothing in this book that did not have to be there — from the blind drunk of the spacebars to the wicked gorgeous Princess, Ruby Red; from the syntax-inversion of the Pleiades speech-pattern to Katin’s erudite lectures; from the cool halls of the Alkane Institute to the hole in the stellar doughnut. The problem is rather that some elements are so compressed as to be almost invisible, and I question whether any reader who lacks the responsibility of recording his opinion will work as hard as I did to find, and put together, all the pieces in a book so readily readable and pleasingly paced on the surface that there is no real cause to wonder how deep the channels underneath may flow — and small sign of their turbulence.

These are (at least some of) the ways you can read Nova: as a fast-action far-flung interstellar adventure; as archetypal mystical/mythical allegory (in which the Tarot and the Grail both figure prominently); as modern-myth told in the s-f idiom with powerful symbols built on solid science fiction clichés; as a futuristic vehicle for a philosophic complex of political/historical/economic/sociological ideas; as an experimental approach to literary criticism.

Among other things, the book examines: the nature and value of scholarship, mysticism, “progress,” and the varieties of the creative experience; the significance of the “instinct for workmanship” (the quote is from Veblen, not Delany) and the alienation phenomena of the industrial and (current) electronic revolutions; the relationships between the psychophysiology of the individual and the ecology of the body politic. Each of the three central characters (or the three aspects of the character?) suffers a variant form of alienation, rooted in different combinations of social, economic, geophysical, cultural, intellectual, and physiological factors. Through one or another of these viewpoints, the reader observes, recollects, or participates in a range of personal human experience including violent pain and disfigurement, sensory deprivation and overload, man-machine communion, the drug experience, the creative experience — and interpersonal relationships which include incest and assassination, father-son, leader-follower, human-pet, and lots more.

The economy of Delany’s writing is both maddening and delightful — and almost accomplishes what he seems to have been trying to do. (For instance, the culture-vista opened up when the Lunar scholar, Katin, says to the gypsy Mouse: “If somebody had told me I’d be working in the same crew, today in the 31st century, with somebody who could honestly be skeptical about the Tarot, I don’t think I would have believed it. You’re really from Earth?”) But even 279 closely written, richly embroidered, tautly thought pages are not enough: it is too much of too many, and too little of each: and — add odd complaints — it is too easy to read, on the easiest level.

If you let yourself go, it will run away with you; since the author failed to set up stop signs, the reader must either make his own (put the book down and pace the room once between chapters?) or plan on a second, slower reading after the fun of the first. Or settle, of course, for a good read, and never mind mining out the gold.

For two writers so disparately individual in concept, mood, style, background, and viewpoint Delany and R. A. Lafferty have certain startling distinctions in common. There are other notable stylists and fine prose writers in s-f today; but — in very different modes — Lafferty and Delany are currently the two outstanding poetic writers (language both lyrical and precise; images exact and evocative). There are other evolving new concepts and working out appropriate new techniques for contemporary multiplexities; and there are many others writing action-adventure yarns in the s-f idiom; but I can think of no others who so frequently manage to combine these apparently contradictory efforts.

But their greatest similarity also contains their most symptomatic difference. Among the characters in both men’s stories, a strange breed of children appear repeatedly: hardheaded/mystical creatures with electric personalities and powerful capacities. In Delany’s stories they are most often young teenagers whose essentially heroic proportions and proclivities (like almost all Delany characters) are dramatically flawed, or defective, or incurably disadvantaged, in some one area. Lafferty’s children are mostly prepubescent, and perfectly normal — except for a total lack of (parental or personal) inhibition; and a sort of amplification — of reality which permits them to act out archetypal childish fantasies on a grand-opera heroic scale.

By the way, Nova, as well as Babel-17 and Dhalgren have been recently produced for audio, and are available at Audible.com. I waited over a decade for Delany to come to audio, and the wait was well worth it, because hearing Delany read by a professional makes his rich narrative come alive in myriads of ways my own inner voice fails to find. I beg the audiobook producer gods to please come out with Distant Stars and Aye, and Gomorrah: And Other Stories next. They contain the short novel and novella, Empire Star and “The Star Pit” which are my absolute favorite science fiction stories form the 1960s.

By the way, Nova, as well as Babel-17 and Dhalgren have been recently produced for audio, and are available at Audible.com. I waited over a decade for Delany to come to audio, and the wait was well worth it, because hearing Delany read by a professional makes his rich narrative come alive in myriads of ways my own inner voice fails to find. I beg the audiobook producer gods to please come out with Distant Stars and Aye, and Gomorrah: And Other Stories next. They contain the short novel and novella, Empire Star and “The Star Pit” which are my absolute favorite science fiction stories form the 1960s.

If you’re the kind of science fiction fan I am, old and looking backwards, analyzing a lifetime of reading, The Merril Theory of Lit’ry Criticism is a book you won’t want to miss. The ebook is a real convenience, letting us read a few reviews on our phones whenever a free moment pops up.

Judith Merril also wrote science fiction, not much, but enough to make her one of the pioneer women writers of science fiction starting in 1948 with her classic short story, “That Only a Mother” appearing in Astounding. She wrote two novels on her own, Shadow on the Hearth (1950) and The Tomorrow People (1960), and two novels with C. M. Kornbluth as Cyril Judd, Gunner Cade (1952) and Outpost Mars (1952). Shadow on the Hearth and the two Cyril Judd novels have been collected by NESFA Press as Space Out: Three Novels of Tomorrow by Judith Merril and C. M. Kornbluth. The Tomorrow People is currently in print from Armchair Fiction, a company that reprints a great deal of forgotten science fiction.

Judith Merril also wrote science fiction, not much, but enough to make her one of the pioneer women writers of science fiction starting in 1948 with her classic short story, “That Only a Mother” appearing in Astounding. She wrote two novels on her own, Shadow on the Hearth (1950) and The Tomorrow People (1960), and two novels with C. M. Kornbluth as Cyril Judd, Gunner Cade (1952) and Outpost Mars (1952). Shadow on the Hearth and the two Cyril Judd novels have been collected by NESFA Press as Space Out: Three Novels of Tomorrow by Judith Merril and C. M. Kornbluth. The Tomorrow People is currently in print from Armchair Fiction, a company that reprints a great deal of forgotten science fiction.

Merril produced several short story collections: Out of Bounds (1960), Daughters of Earth (1968), and Survival Ship and Other Stories (1974), each of which has been repackaged a number of times, but all her stories are currently available as Homecalling and Other Stories: The Compete Solo Short SF of Judith Merril (2005), again from NESFA Press.

I hope both the NESFA books come to audio.

Clifford Simak Doubts His Religion

Clifford D. Simak became the third SFWA Grand Master in 1977, but few contemporary SF fans know his work today. A Heritage of Stars is one of his later books, one so obscure that Wikipedia doesn’t even have an entry for this 1977 novel. Simak was born in 1904, and died in 1988, so A Heritage of Stars was written in his mid-seventies, towards the end of his career. I think that’s significant because the book feels like a summation of Simak’s thoughts on science fiction. I know the older I get, the more I want to make sense of a lifetime of reading science fiction.

Clifford D. Simak became the third SFWA Grand Master in 1977, but few contemporary SF fans know his work today. A Heritage of Stars is one of his later books, one so obscure that Wikipedia doesn’t even have an entry for this 1977 novel. Simak was born in 1904, and died in 1988, so A Heritage of Stars was written in his mid-seventies, towards the end of his career. I think that’s significant because the book feels like a summation of Simak’s thoughts on science fiction. I know the older I get, the more I want to make sense of a lifetime of reading science fiction.

We’ve been reading A Heritage of Stars in my book club this month, and the consensus was it’s ho-hum. However, this is my second reading, and the story has improved — significantly. Simak cranked out sixteen novels in the last two decades of his life. Most of them have no entries on Wikipedia. Simak is famous for City (1952) and Way Station (1963), with his first story published in a 1931 issue of Wonder Stories. He wrote science fiction for six decades!

When you consider Simak’s unique perspective, A Heritage of Stars, takes on new meaning. It’s still just an average SF novel cranked out by a prolific writer, but I think it has something insightful to say about the genre we all love. I met Simak at a convention around this time, and I was shocked by how this Grand Master was ignored by young fans. Star Wars had just come out, and new fans were streaming into fandom. At the con they flocked to guests from media related science fiction, not old writers. Simak even looked from the past.

Writers of Simak’s era wrote science fiction as a gospel preaching promises of wondrous futures. Today, science fiction has become something different. Stories are often like fantasy, good storytelling and entertainment, with a bit of pop culture wisdom. Modern science fiction appears to inhabit the dreams of science fiction past. Something happened to science fiction when we stopped going to the Moon in 1972, and then spent over forty years just circling the Earth. NASA in the 1960s, with Projects Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo felt like it had grown out of 1950s Astounding Stories. Reading science fiction in the 1960s convinced fans we’d get to Mars in the 1970s, and the rest of the solar system by the 1990s. The 21st century would be beyond amazing. Here it’s 2016, and we’re still just jawboning about going to Mars. What happened?

Science fiction came of age with Simak in the 1950s, and peers like Heinlein, Asimov, Norton, Williamson, and Clarke. 1950s science fiction asked a lot of questions and generated its own theology. Science fiction’s true believers knew humans would go to the stars, build intelligent robots and evolve psychic powers. That’s the heaven 1950s science fiction promised, the collapse of civilization was its hell and brimstone.

A Heritage of Stars is Simak’s reevaluation of that theology. This is not a book review, so I’m going to give spoilers. If you don’t want to know them, read no further.

One thing that came through loud and clear in this novel is the legacy of L. Frank Baum and his Oz books. I read the fourteen canonical Oz books when I was a child in the early 1960s. Writers like Simak and Heinlein read them in the 1910s. Oz books became a tradition, published in time for Christmas. The original series ran from 1900-1920. Shelves of dissertations could be written on the impact of Oz books on science fiction writers. But there’s something else to note. Around the time the country was banning DC Comics, librarians decided not to carry Oz books because they claimed those books inspired unrealistic expectations in children. Couldn’t we say that about science fiction too?

Full Details

Full Details