Philip K. Dickathon: Martian Time-Slip

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

Philip K. Dick just couldn’t be bothered by some of the standard verities of science fiction. He knew SF should often take place in outer space, but whereas other novelists placed their narratives in the 2200’s, 2300’s, or some unimaginable distant future, in the novels Dick wrote in the 1950’s and 1960’s, he thought that 40 or so years was plenty of time for man to start populating the universe. He also didn’t pay much attention to the news coming out from astrophysicists that the weather on other planets seemed to be uniformly bad. Martian Time-Slip takes place in 1994. Mars has scattered settlements and townships, mostly sponsored by national groups from Earth. The exception, and the most powerful group of all, is a Plumbers Union. I assume Dick had had some unpleasantness involving plumbers when he sat down to write this book.

Philip K. Dick just couldn’t be bothered by some of the standard verities of science fiction. He knew SF should often take place in outer space, but whereas other novelists placed their narratives in the 2200’s, 2300’s, or some unimaginable distant future, in the novels Dick wrote in the 1950’s and 1960’s, he thought that 40 or so years was plenty of time for man to start populating the universe. He also didn’t pay much attention to the news coming out from astrophysicists that the weather on other planets seemed to be uniformly bad. Martian Time-Slip takes place in 1994. Mars has scattered settlements and townships, mostly sponsored by national groups from Earth. The exception, and the most powerful group of all, is a Plumbers Union. I assume Dick had had some unpleasantness involving plumbers when he sat down to write this book.

But plumbers are essential to the workings of the settlements. The weather is bearable if a little dry. One good trade-off is that you only weigh about fifty pounds, and housewives slip into halter-tops and Capri pants to visit neighbors. But water is in short supply and closely rationed. Arnie Kott, the vulgarian union boss, is one of the richest and most powerful men on the planet, although that may change. Rumor has it that the U.N. is planning to develop the FDR Mountains, drilling deep water wells and creating self-sustaining luxury living complexes. The land grab is on.

Wikipedia has a coherent synopsis of the book, and I congratulate whoever wrote it. Topics touched on include: schizophrenia (which is almost epidemic), black marketing, adultery, extensive drinking and drug ingestion, pesky neighbors — in other words, it is Dick’s Northern California neighborhood transfered to Mars. Much of the plot hinges on Manfred, an autistic child who becomes a test subject for the main character’s experiments with extrasensory communication and ultimately time travel.

And let’s not forget the Beakmen, the remnants of the Martian race who are now reduced to wandering the deserts or working in the homes of wealthy earthlings. Dick always presents himself as progressive in terms of race and social policies in general, but his portrait of the Beakmen is among his strangest concoctions. Just as he didn’t care much for astrophysics, Dick also didn’t seem to keep up with physical anthropology. The Beakmen are described as "Negroid" and descended from the same source as earthly Africans. (Phil, all homo sapiens come from common stock, long predating any division into races. And so unless you are saying some Central African natives somehow found their way to Mars 30,000 years ago, you are really off on this one.) Also, this is a novel written in the early sixties, and Dick was certainly aware of the Civil Rights movement. So what does it mean that Mars has a society somewhat reflecting the Antebellum South? The word slave is never used, but wealthy settlers have "tame" Beakmen working for them, refer to them as niggers, and enjoy giving them such high-falutin’ names as Heliogabalus. But of course, the Beakmen have deep, secret knowledge. Where was Dick going with this?

This is one of Dick’s enjoyable train wrecks of a novel. I don’t want to slip into biographical criticism, but it reads like a combination of Dick’s marital problems, his extensive experience with psychiatrists, a general dislike of land speculators and plumbers, and some cock-eyed ideas about autism. And as nutty as the whole thing is, the conclusion is not only satisfying on many levels but genuinely strange as well.

Philip K. Dickathon: The Man in the High Castle

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

I’ve never been big on Alternate History novels. Never been tempted by those Harry Turtledove books that show spacecraft flying Confederate flags or Doughboys crouching behind armor-plated dinosaurs. But this is Dickian alternative history, and The Man in the High Castle is the novel that won him the Hugo award. He claims in a letter from the mid-sixties that he was not that crazy about this book. Maybe like Henry James he craved success but then tended to look down on works that brought him the most attention. In James’ case it was Washington Square, Daisy Miller, and The Turn of the Screw. And that is the only comparison I would ever think to make between Philip K. Dick and Henry James.

I’ve never been big on Alternate History novels. Never been tempted by those Harry Turtledove books that show spacecraft flying Confederate flags or Doughboys crouching behind armor-plated dinosaurs. But this is Dickian alternative history, and The Man in the High Castle is the novel that won him the Hugo award. He claims in a letter from the mid-sixties that he was not that crazy about this book. Maybe like Henry James he craved success but then tended to look down on works that brought him the most attention. In James’ case it was Washington Square, Daisy Miller, and The Turn of the Screw. And that is the only comparison I would ever think to make between Philip K. Dick and Henry James.

The Allies have lost WWII. The United States is now officially only those states on the Eastern seaboard, and they are under Reich Rule. No one has shown much interest in the Midwest, and, although still part of a conquered empire, it exists as a marginally freer buffer zone. The Japanese control the Pacific States of America, and the bulk of the novel takes place in San Francisco. In the PSA, most Americans have made their peace with the Japanese occupation. No Patrick Swayze has risen to the fore and led a group of teenagers, strangely proficient in advanced military weaponry, to stage a Red Dawn style insurgency. Most San Franciscans are working profitably with, or for, the Japanese, but in alliances that are marked with crippling levels of anxiety. This is, after all, a Philip K. Dick novel.

Dick establishes a dozen or so characters, several of whom are even who they claim to be, and sets things rolling so that paths seemed destined to cross in disastrous ways. But in fact things run rather smoothly with the exception of a couple of spectacular outbreaks of violence. This is a novel of anxiety, not action. It’s a story where anxiety can arise from the excruciating decision of what will be the proper gift to "graft" in a given situation, or by the discovery that the Nazi’s are planning a massive nuclear holocaust. Linked characters are scattered across the continent, and I was worried that somehow everything was going to tie together neatly as in one of the machines-for-winning-Academy-Awards like Crash. But the stories run parallel more often than they cross. One character does save another’s life, but he never meets the man and acts because he is pissed off and wants to exert some authority.

And then there is "the man in the high castle," the reclusive author Hawthorn Abendsen — how does Dick think up these names? Abendsen is the author of the controversial and absurdly titled novel The Grasshoper Lies Heavy. This is an alternative history in which the allies win the war, and although banned by the Nazis, Japanese and American readers are snatching it up. The final question in Dick’s novel centers on the possibility that Abendsen’s novel is not fiction. The Allies did win the war. History is not a progression of events but an infinite play of possibilities. But still a play where some people get killed, some go insane, and some plan to blow the whole thing up.

Philip K. Dickathon: The Cosmic Puppets

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

If written today, The Cosmic Puppets could have been Philip K. Dick‘s foray into YA fantasy fiction. He would have needed to change the protagonist into a plucky teenager instead of a full-grown man, but other than that all the elements are in place.

If written today, The Cosmic Puppets could have been Philip K. Dick‘s foray into YA fantasy fiction. He would have needed to change the protagonist into a plucky teenager instead of a full-grown man, but other than that all the elements are in place.

On a road trip to Florida with his almost estranged wife, Ted Barton wants to stop off at Millgate, the Virginian town he left as a young man eighteen years before. They find the town, but everything about it has changed. (Cue the Twilight Zone theme music here.) Street names, buildings, people, everything is different and slightly decrepit. Then Ted finds his name in an old newspaper, a victim of scarlet fever in 1935.

The Cosmic Puppets is pure fantasy — no science fiction involved. There are two children, Peter who makes tiny clay golems to report of Ted’s movements, and Mary who gets regular reports from moths and bees on Peter’s activities. Mary and Peter do not get along. Peter reveals to Ted the enormous beings who make up the valley’s mountainsides and whose heads reach into the heavens. Little Millgate, Virginia, has become the host of an epic battle between the forces of good and evil. (Just their bum luck.) Ted and the town drunk who somehow escaped "the change" have to will the real Millgate back into existence.

There are some creepy elements here, mostly dependent upon how you feel about spiders and rats. But the Twilight Zone theme continues to hum along in the background, and Rod Serling could make an appearance at any moment.

Philip K. Dickathon: Vulcan’s Hammer

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

Even Lawrence Sutin, PKD’s biographer, refers to Vulcan’s Hammer as dreck. As per usual for Dick’s novels of this period, there has been a devastating war in the 1970’s, and this time around humanity’s bad idea for how to handle post-war society it to turn everything over to computers. These machines’ decisions will be based purely on logic, war will come to an end, but of course an elaborate police system must be put into place to maintain this logical utopia. Underground movements are breaking out across the globe.

Even Lawrence Sutin, PKD’s biographer, refers to Vulcan’s Hammer as dreck. As per usual for Dick’s novels of this period, there has been a devastating war in the 1970’s, and this time around humanity’s bad idea for how to handle post-war society it to turn everything over to computers. These machines’ decisions will be based purely on logic, war will come to an end, but of course an elaborate police system must be put into place to maintain this logical utopia. Underground movements are breaking out across the globe.

The computer has had three incarnations, Vulcan I, Vulcan II, and the current Vulcan III that only one man can access in its impregnable stronghold deep underground in Switzerland. The current director maintains a fondness for dusty old Vulcan II. He enjoys making the punch cards that feed it information and then reading the printouts it releases, although those messages now take up to a day or so to appear. There’s something a little creepy about Vulcan III with its digital screens and its suspicion that its humans are not telling it the whole story. Of course, Vulcan III decides to take matters into its own hands.

Dick’s novel has all the pieces in place but then has nowhere to go with them. The conclusion is as predictable as it is anti-climactic. Vulcan’s Hammer was the "B side" of an Ace Double, so it has if nothing else the virtue of brevity.

Automata 101: Robots and the Mechanical Age

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. This blog will outline her experiences teaching an Honors English Composition course about created entities, beginning with the golem of Jewish legend and continuing through cyborgs, robots, androids, and artificial intelligence.

This section focuses on two texts and a film: Karel Capek’s play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and Isaac Asimov’s collection of short stories and essays Robot Visions. I chose the latter instead of the more popular I, Robot for two reasons. First, the number of stories plus their mixture with essays gave me a great choice of texts. The essays provided the students with some background and analytical exploration of robots. The second reason is the collection contained the novelette The Bicentennial Man, which I wanted to teach to provide a longer example of Asimov’s work. The students were excited to get to robots, the shiny humanoid forms, after the automata of the previous section.

This section focuses on two texts and a film: Karel Capek’s play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and Isaac Asimov’s collection of short stories and essays Robot Visions. I chose the latter instead of the more popular I, Robot for two reasons. First, the number of stories plus their mixture with essays gave me a great choice of texts. The essays provided the students with some background and analytical exploration of robots. The second reason is the collection contained the novelette The Bicentennial Man, which I wanted to teach to provide a longer example of Asimov’s work. The students were excited to get to robots, the shiny humanoid forms, after the automata of the previous section.

We began with Capek’s play, which gave the world the word “robot,” which is the Czech word for “serf.” Capek’s dystopic play, performed and published in 1921, is very concerned with the rights of the worker. It appeared in a time and a place where communism, socialism and capitalism were beginning to clash. The play enjoyed international success, debuting on Broadway in 1922 and in the West End in 1923. By the time it was performed in London, the play had been translated into thirty languages and performed in many other cities.

While the students’ expectations of CP3O-like robots were not exactly met, they were not disappointed. They learned that these “original” robots of R.U.R. were not mechanical at all but were instead organic in composition. However, this fact does not matter too much because the mechanical mode of production Capek describes puts one in mind of Henry Ford’s assembly line with robots working to produce more robots ad nauseum. We talked a lot about Capek’s world and why a world freed from work might be appealing, especially when many workers of the time felt as if they were dehumanized and only a part of the machinery of capitalism.

While the students’ expectations of CP3O-like robots were not exactly met, they were not disappointed. They learned that these “original” robots of R.U.R. were not mechanical at all but were instead organic in composition. However, this fact does not matter too much because the mechanical mode of production Capek describes puts one in mind of Henry Ford’s assembly line with robots working to produce more robots ad nauseum. We talked a lot about Capek’s world and why a world freed from work might be appealing, especially when many workers of the time felt as if they were dehumanized and only a part of the machinery of capitalism.

I structured the class so that the students read the Prologue and Act 1 for a Monday, on Wednesday we watched excerpts of Metropolis in class, and then we finished the play on Friday. Showing them Metropolis really helped them visualize how Capek thought about labor. The class is only 50 minutes, so I had to choose sections of the movie carefully. We focused on the first few minutes that juxtapose the workers at shift change with the rich boy Freder in the Eternal Gardens. The second section we watched was the explosion of the M-Machine in the factory, and finally we watched Maria’s transformation into the “machine-man.” Some of these moments are in this restoration trailer. (The students did finally get their shiny robot.)

We concluded our discussion of R.U.R., focusing on the character of Helena, who through her desire to be a do-gooder, dooms mankind to extinction. Many of them noticed that Helena represented the upper class who wanted to improve the world but did not know the price of a loaf of bread. She has the charm of her namesake, Helen of Troy, and uses it to convince Dr. Gall to give the robots souls. This change created a new race of robots, who suddenly cared that they were working for beings who were weaker and dumber than they were. This caused the worldwide revolt and slaughter of all of humanity, except for one man who could build any more robots because Helena had destroyed the formula as a last-ditch effort to remedy her mistakes.

We concluded our discussion of R.U.R., focusing on the character of Helena, who through her desire to be a do-gooder, dooms mankind to extinction. Many of them noticed that Helena represented the upper class who wanted to improve the world but did not know the price of a loaf of bread. She has the charm of her namesake, Helen of Troy, and uses it to convince Dr. Gall to give the robots souls. This change created a new race of robots, who suddenly cared that they were working for beings who were weaker and dumber than they were. This caused the worldwide revolt and slaughter of all of humanity, except for one man who could build any more robots because Helena had destroyed the formula as a last-ditch effort to remedy her mistakes.

The ending of the play is ambiguous but points toward a super-evolved robot couple, Primus and Helena (named after the character), repopulating the earth the old-fashioned way. The Robot Helena is a commentary on her namesake. Dr. Gall remarks: “She is as lovely and foolish as the spring. Simply good for nothing.” Unlike the sterile human Helena, she developed the ability to procreate and with Primus (whose name means “first”) becomes, the new Adam and Eve.

The ending of the play is ambiguous but points toward a super-evolved robot couple, Primus and Helena (named after the character), repopulating the earth the old-fashioned way. The Robot Helena is a commentary on her namesake. Dr. Gall remarks: “She is as lovely and foolish as the spring. Simply good for nothing.” Unlike the sterile human Helena, she developed the ability to procreate and with Primus (whose name means “first”) becomes, the new Adam and Eve.

We noticed that Capek, like Mary Shelley, was not interested in the science of robot creation; Isaac Asimov, however, adds the concept of the positron brain and his three laws to bring in some science. I tried to choose stories that demonstrated Asimov’s exploration of his robots’ humanity, such as “Robbie,” “Evidence,” and “Robot Vision.” (Personally, I prefer the puzzle stories that demonstrate robots acting strangely because the laws are in conflict or a human gives a confusing order, such as “Runaround” or “Little Lost Robot.”)  We also read essays in which Asimov explored why humanity would make robots in a human shape (“The Friends We Make”) and what mankind would do if robots replaced it as workers (“Whatever You Wish”). The second one provided an interesting counterpoint to R.U.R.

We also read essays in which Asimov explored why humanity would make robots in a human shape (“The Friends We Make”) and what mankind would do if robots replaced it as workers (“Whatever You Wish”). The second one provided an interesting counterpoint to R.U.R.

The students wrote papers that connected the ideas emerging in this section back to earlier ones. Some explored two reasons that humans fear robots in Asimov’s stories and Capek’s play. Others tried to define Asimov’s term “Frankenstein Complex,” which he never really defines, and to investigate its implications. I asked them to argue if Asimov’s use of the term seems to perpetuate or combat the Frankenstein Complex. Only one student chose the creative option to write a dialog between Capek and Asimov discussing robots, humans and work. All of these themes will transition us nicely to the next section which contains Marge Piercy’s He, She and It and Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Philip K. Dickathon: Dr. Futurity

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

I hope Phil was able to pay some bills with whatever money he got from Dr. Futurity. It is filled with the kind of prose that sounds like the author is thinking through what his character might do next, making notes rather than telling a story.

I hope Phil was able to pay some bills with whatever money he got from Dr. Futurity. It is filled with the kind of prose that sounds like the author is thinking through what his character might do next, making notes rather than telling a story.

This one is definitely for completists only.

Philip K. Dickathon: Time Out of Joint

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

Throughout the 1950’s, Philip K. Dick continued to write mainstream novels involving working class characters and realistic situations. His agents were never able to place any of these titles with publishers, at least not until several years after Dick’s death when the Dickian industry began in earnest and publishers were scrounging for new material. Dick sometimes disparaged his sf output, but he continued to have faith in these realist novels into the 1960’s.

Throughout the 1950’s, Philip K. Dick continued to write mainstream novels involving working class characters and realistic situations. His agents were never able to place any of these titles with publishers, at least not until several years after Dick’s death when the Dickian industry began in earnest and publishers were scrounging for new material. Dick sometimes disparaged his sf output, but he continued to have faith in these realist novels into the 1960’s.

Time out of Joint, published in 1959, is a science fiction story that reads, for much of the time, as one of Dick’s mainstream efforts. The characters are middle management types, one manages the produce department of a local grocery store, another works for the water department. They live in a new suburb of modest homes and are somewhat civically active. One couple, Vic and Margo, share their home with Margo’s brother, Raigle, a war veteran who makes a comfortable living by answering a daily newspaper quiz, Where Will the Little Green Man Land Next. He is always right and has become something of a celebrity.

The first odd moment arrives when Vic looks through a newly arrived brochure from the Book-of-the-Month Club and wonders who Harriet Beecher Stowe might be. It’s possible he wouldn’t know, but later Raigle sees a layout in Life Magazine and marvels that the featured starlet’s breasts can maintain the tilt they have in the photographs. Since this is a Philip K. Dick novel, all three characters analyze the breasts in some detail but then also wonder among themselves just who Marilyn Monroe could be that she would merit so much attention.

The next day, while Raigle contemplates adultery with the neighbor’s wife, he takes her to the municipal swimming pool, and when he goes to the refreshment stand for cokes, the stand and its manager fade from sight leaving behind only a piece of paper with the printed words SOFT-DRINK STAND. Raigle puts the note into a box he keeps in his pocket where similar messages read DOOR, FACTORY BUILDING, BOWL OF FLOWERS.

We are now in Dickian territory, where few people are who they claim to be, and a trip past the city limits is a trip to another world. Dick earns his standing as the connoisseur of American paranoia with this one. Early on Raigle has the insight that he may be the most important person in the world. He’s no dummy.

Philip K. Dickathon: The World Jones Made

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

Philip K. Dick published The World Jones Made in 1956 and didn’t give "life as we know it" much time. A devastating world war breaks out in the 1970’s, but humankind proves remarkably resilient. By the mid 1990’s, when the story begins, we are already zipping around town in airborne taxis and traveling cross country in the matter of an hour or so. You may live in Detroit but you party in San Francisco. "Relativity" is the accepted philosophy of the day, and I found it one of Dick’s vaguer concepts. People can not only do most anything they want, but they must let others do so as well, and they cannot, under any circumstances, express a belief in anything. This live and let live code must be enforced by an elaborate security police force, and Cussick, the central character, is on the force.

Philip K. Dick published The World Jones Made in 1956 and didn’t give "life as we know it" much time. A devastating world war breaks out in the 1970’s, but humankind proves remarkably resilient. By the mid 1990’s, when the story begins, we are already zipping around town in airborne taxis and traveling cross country in the matter of an hour or so. You may live in Detroit but you party in San Francisco. "Relativity" is the accepted philosophy of the day, and I found it one of Dick’s vaguer concepts. People can not only do most anything they want, but they must let others do so as well, and they cannot, under any circumstances, express a belief in anything. This live and let live code must be enforced by an elaborate security police force, and Cussick, the central character, is on the force.

Jones threatens this world because he is a prophet, able to see into the future for up to one year. This means that the future is known, it is a sure thing, and so the Relativity world will fall apart. The mob longs for Jones’s message and forms a devoted following that transforms into a worldwide movement. He can’t be stopped because he already knows every move that will be made against him. Cussick’s gorgeous Scandinavian wife aligns herself with the Jones movement and becomes a senior officer in the organization. There is a subplot concerning human mutants specially bred to survive on Venus, and an inconvenient but not very dangerous invasion of giant space amoebas that the Jones followers raucously destroy.

All of this does not make into a very coherent novel, and, for as nutty as much of it is, The World Jones Made is a little downbeat for Dick. The characters, other than Jones, are exhausted and justifiably pessimistic, caught up in defending a world order they know is doomed and which they no longer really believe in. No wonder they go to night clubs and make concoctions of heroin and marijuana their first drink of the night.

Philip K. Dickathon: The Man Who Japed

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll be posting one every week until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

I was going to say that The Man Who Japed was for Philip K. Dick completists only, but then I read that in the mid 60’s he considered it the best thing he had written to date. And this was after Man in the High Castle had won the Hugo Award.

I was going to say that The Man Who Japed was for Philip K. Dick completists only, but then I read that in the mid 60’s he considered it the best thing he had written to date. And this was after Man in the High Castle had won the Hugo Award.

I don’t know why he was so fond of it. The Man Who Japed was originally half of an Ace Double, so it could pass as a novella. It is also just one of about five book-length works Dick wrote or put under copyright in 1956. Familiar PKD elements are all in place: a postwar dystopian future, a lone hero going against the code, incredibly fast pacing, digs at psychiatry, a brief trip to another planet. This is a moral world where the morality is enforced by neighborhood watch societies headed by middle-aged women in floral print dresses. (Such beings seem to be a particular horror to PKD. They show up in Eye in the Sky as well.) The ladies get their information from "the juveniles," two-foot-long mechanical centipedes charged with keeping a watch on things. Alan Purcell is part of this system. He works in a form of advertising that broadcasts campaigns with moral lessons that are good for the populace. During the course of the book he falls very afoul of the system and plots to overthrow it.

Satire and action here are good, but Dick’s most prescient insights have to do with real estate. In the 22nd century people with tiny apartments close to the center of town live in fear of code violations that will exile them to what I suppose are tenements or something equally unpleasant further out.

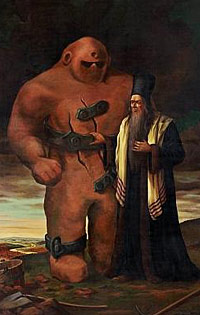

Automata 101: Introduction

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. This blog will outline her experiences teaching an Honors English Composition course about created entities, beginning with the golem of Jewish legend and continuing through cyborgs, robots, androids, and artificial intelligence.

This semester I’m teaching a course that examines the relationship between humans and created beings. (I wish I had a catchier name, but "created beings" seems to cover the various organic, mechanical and digital creatures that inhabit my syllabus.) Since the Worlds Without End site, especially the sub-genre lists, was instrumental in my syllabus development, I decided to share my reading list in the forum. From there, Dave, Rico and I decided that it might be interesting if I blogged about my experiences and those of my students. This first blog will serve as an overview while the subsequent ones will focus on specific texts or issues.

This semester I’m teaching a course that examines the relationship between humans and created beings. (I wish I had a catchier name, but "created beings" seems to cover the various organic, mechanical and digital creatures that inhabit my syllabus.) Since the Worlds Without End site, especially the sub-genre lists, was instrumental in my syllabus development, I decided to share my reading list in the forum. From there, Dave, Rico and I decided that it might be interesting if I blogged about my experiences and those of my students. This first blog will serve as an overview while the subsequent ones will focus on specific texts or issues.

First, a bit about the class: Coker College offers one section of Honors Composition each semester. The students are all good readers and writers as well as enthusiastic and industrious — a pleasure to teach. Most of them are first-semester, first-year students. Often it is a challenge to find literary texts that these students have not studied in their AP or Honors English classes or read on their own, so I always try to pick out-of-the-mainstream texts that most of them have not read or often have not heard about.

This year my inspiration for the course is the keynote speaker for the Coker College Undergraduate Humanities Conference in February. He is J. Andrew Brown, author of Cyborgs in Latin America. (You can download a free copy of the book here.) The conference co-founder, Dr. Mac Williams, is an Assistant Professor of Spanish, and he informed me that there are many innovative Hispanophone novels that explore the relationships between technology and humanity, posthumanity, and the like. I decided that this would be a great way to tie my recreational reading with a class whose goal would be to have student papers worthy for presentation at the conference in February. This type of presentation will be a new experience for freshman students who usually don’t have such opportunities.

In the class, we will read novels, short stories, essays, and articles from social science journals and popular magazines. We will also watch movies. I will talk about the secondary works as I blog about each section, but in this overview it is my intention to discuss each section and the primary works in it.

In Frankenstein’s Monster as Golem, we will apply several texts about the Golem and creation to Mary Shelley‘s Frankenstein. The primary questions we will explore in this section are: Why does Victor Frankenstein try to create a being? What is his responsibility to the being once created? What is at stake when one pushes the boundaries of science and knowledge? Can scientists/inventors ever "get it right" if they are afraid to "get it wrong"?

In Frankenstein’s Monster as Golem, we will apply several texts about the Golem and creation to Mary Shelley‘s Frankenstein. The primary questions we will explore in this section are: Why does Victor Frankenstein try to create a being? What is his responsibility to the being once created? What is at stake when one pushes the boundaries of science and knowledge? Can scientists/inventors ever "get it right" if they are afraid to "get it wrong"?

In Gothic Romance and the Uncanny, we will read several short texts — E. T. A. Hoffmann‘s stories, "The Sandman" and "The Automata," Edgar Allan Poe‘s essay, "Maelzel’s Chess Player," and F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre‘s "The Clockwork Horror," which is a retelling of Poe’s essay. My goal in this section is to introduce the students to the concept of the uncanny. The texts all focus on 19th century "robots," or clockwork beings, which will allow us to test the boundaries of what makes these machines uncanny.

In Gothic Romance and the Uncanny, we will read several short texts — E. T. A. Hoffmann‘s stories, "The Sandman" and "The Automata," Edgar Allan Poe‘s essay, "Maelzel’s Chess Player," and F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre‘s "The Clockwork Horror," which is a retelling of Poe’s essay. My goal in this section is to introduce the students to the concept of the uncanny. The texts all focus on 19th century "robots," or clockwork beings, which will allow us to test the boundaries of what makes these machines uncanny.

In Robots and the Mechanical Age, we will read several of Isaac Asimov‘s stories and essays from Robot Visions and Karel Capek‘s play R. U. R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). We will also watch clips from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. I hope that the movie will help the students understand the context of R.U.R, which is a very powerful piece but a bit didactic in its tone. This section explores what happens when mechanical creatures learn, evolve and start making decisions. We will not ignore the Marxist overtones, but we will also look at these robots as robots and not just as symbols the proletariat. We will examine the texts as explorations of human fears and desires concerning robots.

In Robots and the Mechanical Age, we will read several of Isaac Asimov‘s stories and essays from Robot Visions and Karel Capek‘s play R. U. R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). We will also watch clips from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. I hope that the movie will help the students understand the context of R.U.R, which is a very powerful piece but a bit didactic in its tone. This section explores what happens when mechanical creatures learn, evolve and start making decisions. We will not ignore the Marxist overtones, but we will also look at these robots as robots and not just as symbols the proletariat. We will examine the texts as explorations of human fears and desires concerning robots.

In Cyborgs and Androids, we will focus on the two most intriguing novels of the bunch, Marge Piercy‘s He, She and It and Philip K. Dick‘s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? We will also watch Blade Runner. Unfortunately, this is the section that I have thought the least about. I know we will do some work on defining terms, robot, cyborg, and android and discuss their slipperiness in science fiction writing. We will also continue our discussion that we begun in the previous section about created beings and free will.

In Cyborgs and Androids, we will focus on the two most intriguing novels of the bunch, Marge Piercy‘s He, She and It and Philip K. Dick‘s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? We will also watch Blade Runner. Unfortunately, this is the section that I have thought the least about. I know we will do some work on defining terms, robot, cyborg, and android and discuss their slipperiness in science fiction writing. We will also continue our discussion that we begun in the previous section about created beings and free will.

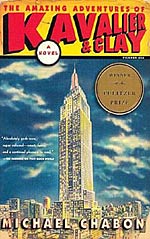

In the final section, The Artist as Golem Maker, we will read Michael Chabon‘s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. The Golem plays a small role in this novel, but this exploration of the origin of comics provides an interesting way into discussing modern and postmodern ideas of creation. I hope that by November many of the ideas we’ve discussed will represent themselves in the guise of the superheroes.

In the final section, The Artist as Golem Maker, we will read Michael Chabon‘s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. The Golem plays a small role in this novel, but this exploration of the origin of comics provides an interesting way into discussing modern and postmodern ideas of creation. I hope that by November many of the ideas we’ve discussed will represent themselves in the guise of the superheroes.

I hope this introduction has piqued your interest and you will send me feedback as I document the course. So far the students have been extremely enthusiastic and we’ve had some great discussions – more on that in my next blog.

Full Details

Full Details