Forays into Fantasy (and Horror): Bram Stoker’s Dracula and the Origin of the Vampire

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

In Greek mythology, the Lamia was a Libyan queen who was transformed into an unclean child-eating demon. The story later became part of European folklore—a story told to frighten misbehaving children. In many versions, the Lamia became a serpentine monster who seductively lured men to their doom, in order to drink their blood. According to Brian Stableford in The Encylopedia of Fantasy, this legend, combined with “Eastern European superstitions regarding cannibalistically inclined reanimated corpses,” were the roots of the literary vampire, although the latter type of story seemed to be more closely related to the modern zombie.

In Greek mythology, the Lamia was a Libyan queen who was transformed into an unclean child-eating demon. The story later became part of European folklore—a story told to frighten misbehaving children. In many versions, the Lamia became a serpentine monster who seductively lured men to their doom, in order to drink their blood. According to Brian Stableford in The Encylopedia of Fantasy, this legend, combined with “Eastern European superstitions regarding cannibalistically inclined reanimated corpses,” were the roots of the literary vampire, although the latter type of story seemed to be more closely related to the modern zombie.

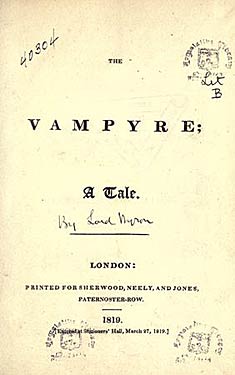

In 1819, John Polidori, formerly Lord Byron’s physician, took a fragmentary story of Byron’s and expanded it into The Vampyre: A Tale, whose vampire protagonist, Lord Ruthven, was seen from the time of the book’s publication to be a thinly disguised portrayal of Byron himself—a character that became the initial template for the modern vampire in horror fiction. Ruthven was “the satanic, world-weary aristocrat whose eyes have a hypnotic effect, especially upon women, and in whom vampirism and seduction are a part of the same process. The languor of the Byronic vampire is a pose, [however,] for his energy is infernal” (John Clute, also from The Encylopedia). See the blog post on Frankenstein’s Forefathers for more on the story of the intertwined origins of the two best-known monsters in horror fiction, involving Byron, Polidori, and Mary Shelley, during the summer of 1816.

In 1872, Sheridan le Fanu, author of numerous supernatural stories and the eerie locked-room mystery Uncle Silas, published a novella called Carmilla, about a female vampire who seduces young women, appearing as a cat-like creature to drink their blood. The lesbian overtones are clear, though never made explicit. Laura, the protagonist who befriends Carmilla and becomes her victim, seems to be the model for Bram Stoker’s Mina in Dracula, while the vampire expert Baron Vordenburg, who organizes the resistance to Carmilla, is the prototype for Stoker’s Van Helsing. Carmilla may also have been the model for the female vampire Lucy in Dracula.

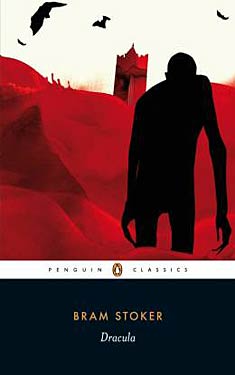

All these influences, then, came together in Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, which put forward the version of the vampire character that became the starting point for almost all subsequent vampire literature and film since. From direct adaptations to the many variations, reactions, and even parodies, Stoker’s version, which combined Polidori’s Byronic aristocratic vampire with many of the plot points found in le Fanu’s Carmilla, and included the sexual undertones of both, is the model. From very early folkloric roots, then, the vampire has come to be an irresistible trope in fantasy and horror—the character that represents a combination of attraction and repulsion; a beautiful monster expressing the psychological uneasiness that surrounds human sexuality. Stoker’s Dracula represents both the near-irresistibility and the potential mystery and danger of intimate relationships, and subsequent writers and filmmakers have expanded on the possibilities of this idea in countless variations.

All these influences, then, came together in Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, which put forward the version of the vampire character that became the starting point for almost all subsequent vampire literature and film since. From direct adaptations to the many variations, reactions, and even parodies, Stoker’s version, which combined Polidori’s Byronic aristocratic vampire with many of the plot points found in le Fanu’s Carmilla, and included the sexual undertones of both, is the model. From very early folkloric roots, then, the vampire has come to be an irresistible trope in fantasy and horror—the character that represents a combination of attraction and repulsion; a beautiful monster expressing the psychological uneasiness that surrounds human sexuality. Stoker’s Dracula represents both the near-irresistibility and the potential mystery and danger of intimate relationships, and subsequent writers and filmmakers have expanded on the possibilities of this idea in countless variations.

Dracula, then, is an important book in the history of horror and fantasy, but does it still hold up as a readable novel over a century after its initial appearance? It’s widely praised as a classic by horror fans and critics alike, but I have to wonder if it hasn’t become somewhat overrated due to its iconic stature. In rereading it, I tried not to be influenced by the fact that the plot has become over-familiar, but that is unavoidably part of what modern readers will bring to it. Much of Stoker’s suspense-building is based on the slow accretion of information about the true nature of the vampire threat, which would work much better with readers who do not already know the story. As a result, the horror is diluted.  The novel is quite long, and the full realization that Dracula is a vampire does not emerge until nearly two-thirds of the way through the book. The first four chapters, detailing Harker’s experience at Dracula’s castle, are eerie and suspenseful—for me, the highlight of the novel—but once the action shifts back to England and Dracula becomes more of a background presence, things slow considerably, and the pace of the plot development began to try my patience.

The novel is quite long, and the full realization that Dracula is a vampire does not emerge until nearly two-thirds of the way through the book. The first four chapters, detailing Harker’s experience at Dracula’s castle, are eerie and suspenseful—for me, the highlight of the novel—but once the action shifts back to England and Dracula becomes more of a background presence, things slow considerably, and the pace of the plot development began to try my patience.

Despite these drawbacks, for the patient reader, I think he novel is still worth reading for those interested in the history of fantasy, as well as for its better moments and its interesting structure. The epistolary approach (the story is told entirely by way of the protagonists’ diaries and letters, and a few relevant news clippings) is an interesting way to immerse the reader in the characters’ slow realization, by way of accumulating evidence, of the true horror they have become involved in.

Also interesting is the role of science in the novel. Van Helsing is presented as one of the leading medical scientists of the time, and yet he must convince the other characters to accept the supernatural explanation for what is happening. For him, it comes down to keeping an open mind and being willing to accept the empirical evidence. (In fact, one of the narrative frustrations is his refusal to explain to the other characters what he thinks is going on until he’s sure they’ve seen enough for them to overcome their disbelief.) If this leads to superstitions being verified, so be it. He then fights vampirism with whatever works, be it blood transfusions or garlic flowers and crucifixes. I’m not sure how this would have come across to a reader in 1897, but it seems an odd juxtaposition now: the ultimate man of science using Christian symbols to fight off a supernatural menace.

As for the writing, the novel contains much extraneous detail as the characters tell their stories, long speeches that might work in the theater but seem artificial here (Stoker was better known at the time for his plays than for his novels), histrionic sentimentality (the male characters’ worship of the feminine perfection of Lucy and Mina gets old quickly), and distracting attempts to phonetically reproduce vernacular speech. I might forgive these problems as artifacts of the time the book was written, if some of the best writing in English had not come from the same period. (It’s doubtful Henry James or Mark Twain were worried about the competition.)

As for the writing, the novel contains much extraneous detail as the characters tell their stories, long speeches that might work in the theater but seem artificial here (Stoker was better known at the time for his plays than for his novels), histrionic sentimentality (the male characters’ worship of the feminine perfection of Lucy and Mina gets old quickly), and distracting attempts to phonetically reproduce vernacular speech. I might forgive these problems as artifacts of the time the book was written, if some of the best writing in English had not come from the same period. (It’s doubtful Henry James or Mark Twain were worried about the competition.)

For readers patient enough to overlook these defects, there are rewards to be had in the novel. If nothing else, those first four chapters are well worth the time, and the book’s place in the history of horror and fantasy is undeniable. But is it still a “must-read” for fantasy or horror fans? I don’t think so. It’s one of those stories that have become so iconic that it’s almost as though we have all absorbed it without actually reading it, by way of all the subsequent stories and films that have channeled it into the present. Its familiarity tends to work against it for a twenty-first century reader, so it’s difficult to judge simply as a literary production, but I came away from my reread thinking of it as a good, but not great, novel. Consider reading the opening “Harker’s Journal” chapters for a Halloween treat. You already now how it ends…

Full Details

Full Details

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.