Forays into Fantasy: Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, in an attempt to understand the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Gormenghast was released in 1950, the same year as The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Lord of the Rings would soon follow. These latter two works may be seen as the defining fantasies of the second half of the twentieth century, altering the landscape of the field, popularizing the secondary world fantasy and setting the stage for the advent of fantasy as a commercial genre in the late 1960s. As well as developing an enduring popularity that continues into the present, these books (especially, or course, The Lord of the Rings) have been more influential on fantasy literature than anything since. And yet, though it is not read as widely as these two contemporaries, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, conceived in that same post-war period in England, seem to me to be just as important. Unlike Tolkien and Lewis, Peake has not inspired hordes of imitators or greatly influenced the direction of commercial fantasy. The influence of Mervyn Peake could not be based on imitating the plot structure or external trappings of his creation—the books are too idiosyncratic for that to be a temptation. Rather, the strand of Peake’s influence can be seen in those writers of modern fantasy who have rejected the commercial allure of Tolkien-like epic fantasy in order to pursue their own personal fantastic visions, and those for whom character, theme, and style are at least as important as plot and exterior world-building.

Gormenghast was released in 1950, the same year as The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Lord of the Rings would soon follow. These latter two works may be seen as the defining fantasies of the second half of the twentieth century, altering the landscape of the field, popularizing the secondary world fantasy and setting the stage for the advent of fantasy as a commercial genre in the late 1960s. As well as developing an enduring popularity that continues into the present, these books (especially, or course, The Lord of the Rings) have been more influential on fantasy literature than anything since. And yet, though it is not read as widely as these two contemporaries, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, conceived in that same post-war period in England, seem to me to be just as important. Unlike Tolkien and Lewis, Peake has not inspired hordes of imitators or greatly influenced the direction of commercial fantasy. The influence of Mervyn Peake could not be based on imitating the plot structure or external trappings of his creation—the books are too idiosyncratic for that to be a temptation. Rather, the strand of Peake’s influence can be seen in those writers of modern fantasy who have rejected the commercial allure of Tolkien-like epic fantasy in order to pursue their own personal fantastic visions, and those for whom character, theme, and style are at least as important as plot and exterior world-building.

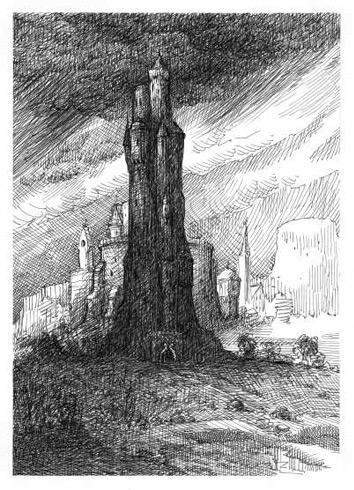

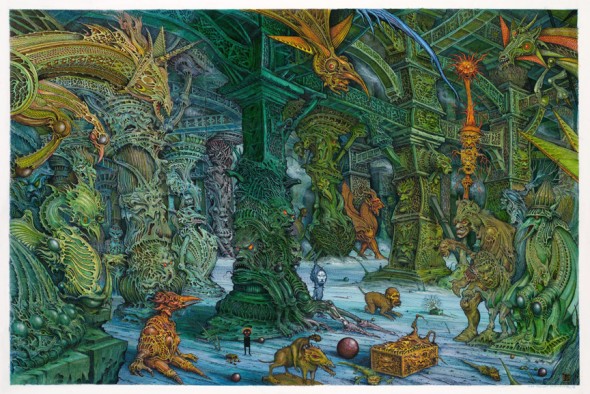

This is not to say that world-building is not important in Peake’s works, but it is not of the sort that epic fantasy fans will be looking for. The inhabitants of Gormenghast can only be defined in relation to the environment their forebears created for them, and this environment—Gormenghast castle and it’s immediate natural surroundings—is described in such visual terms that the setting is evoked in a way rarely achieved, and this setting is arguably more interesting than any individual character. But this world-building is focused interiorly on the isolated castle. There’s no need for a map to track the characters’ progress, and the outside world is never described in the first two Gormenghast novels. This aspect adds to the strangeness and dislocation created by Peake’s writing, since the reader knows nothing of the larger world in which Gormenghast is situated. The result is a strange combination of dislocation and concreteness. We do not know where or when Gormenghast exists, yet it comes to seem entirely real on its own terms. The concreteness of the castle setting is further enhanced by the fact that Gormenghast seemingly has not changed for centuries, possibly millennia (aside from a slow deterioration), and it is this fact that creates the conflict that first become apparent in the first Gormenghast novel, Titus Groan (1946, see previous post), and comes to a head in the second, Gormenghast (1950).

Titus Groan covers the first two years of the life of Titus, the 77th Earl of Gormenghast. “Titus the seventy-seventh. Heir to a crumbling summit: to a sea of nettles: to an empire of red rust: to rituals’ footprints ankle-deep in stone. Gormenghast.” That novel recounts the arrival of the rebel kitchen-boy Steerpike, as he worms his way into the life of the castle, helping move forward the events that lead to the death of Titus’s father Sepulchrave, the 76th Earl, and the banishment of faithful servant Flay—events that, at the beginning or Gormenghast, still reverberate, creating a sense of unease in both Titus’s mother Gertrude, and loyal Dr. Prunesquallor, as well as the banished Flay, who has been living in the wilderness outside the castle and occasionally sneaking in at nightfall to investigate his suspicions. Something they cannot put their fingers on has changed in Gormenghast, and that can’t be a good thing in this unchanging world. All three characters have a sense, though without direct evidence, that the changes began with the arrival of Steerpike.

Titus Groan covers the first two years of the life of Titus, the 77th Earl of Gormenghast. “Titus the seventy-seventh. Heir to a crumbling summit: to a sea of nettles: to an empire of red rust: to rituals’ footprints ankle-deep in stone. Gormenghast.” That novel recounts the arrival of the rebel kitchen-boy Steerpike, as he worms his way into the life of the castle, helping move forward the events that lead to the death of Titus’s father Sepulchrave, the 76th Earl, and the banishment of faithful servant Flay—events that, at the beginning or Gormenghast, still reverberate, creating a sense of unease in both Titus’s mother Gertrude, and loyal Dr. Prunesquallor, as well as the banished Flay, who has been living in the wilderness outside the castle and occasionally sneaking in at nightfall to investigate his suspicions. Something they cannot put their fingers on has changed in Gormenghast, and that can’t be a good thing in this unchanging world. All three characters have a sense, though without direct evidence, that the changes began with the arrival of Steerpike.

The reader already knows that Steerpike is purposefully undermining Gormenghast’s power structure, both for his own personal gain, and because it pleases him to see those born into positions above his own brought down. He takes great pleasure in manipulating the castle’s leaders, and his machinations become increasingly cruel as the story unfolds. Gormenghast is the ultimate conservative society—ritual being the source of all activity, nothing ever changes—so Steerpike’s plan involves maneuvering himself into the position of the Master of Ritual, the person who interprets the ancient texts that determine everything of importance within the castle. He makes himself indispensible to Barquentine, the old, crippled Master, whose readings of the governing texts, which Steerpike studies carefully, determine the life of Gormenghast—activities and rituals which the members of the House of Groan must follow, but which they have long since given up trying to understand. As Titus grows up, he is at once the most powerful and the least free resident of Gormenghast, expected to live out his life as a series of predetermined ritual actions.

When the time is right, Steerpike puts into effect his plan to murder Barquentine and take over his office, but despite the old man’s weakness, he is the embodiment of Gormenghast’s heritage, and his ability to fight back against Steerpike’s attack seems to draw from the castle’s ancient reserves of resistance to the change represented by the upstart: “in his adversary he was pitting himself against Gormenghast.  Before him he had a living pulse of the immemorial castle.” What should be an easy victory for Steerpike becomes a climactic battle between the forces of stability and change, as Barquentine summons “a superhuman effort, one-legged though he was,” to beat back Steerpike’s attack, tenaciously maneuvering them both onto an open flame, and sending them, both afire and gripping each other in hatred, out the castle window and into the moat below.

Before him he had a living pulse of the immemorial castle.” What should be an easy victory for Steerpike becomes a climactic battle between the forces of stability and change, as Barquentine summons “a superhuman effort, one-legged though he was,” to beat back Steerpike’s attack, tenaciously maneuvering them both onto an open flame, and sending them, both afire and gripping each other in hatred, out the castle window and into the moat below.

Steerpike survives to become the Master of Ritual, but at the cost of nearly losing his own life, and having been disfigured by the flames. The battle with Barquentine, though, does seem to be the point at which Steerpike’s ascent is halted, as the death of the Master, despite Steerpike’s own injuries pointing to its having been accidental, increases the suspicions of Gertrude, Prunesquallor, Flay, and now Titus, whose suspicion of the new Master of Ritual, who begins to exert his power over the Earl, rapidly turns to hatred. Titus begins to spy on his tormenter, waiting for him to give himself away, a possibility that grows in likelihood as Steerpike’s activities become ever less careful, his mind unbalanced by his experience with Barquentine and his ongoing battle with the relentless forces of Gormenghast. Titus’s determination only increases when Steerpike begins to implement the next step in his plan—the courtship of Titus’s sister Fuchsia. A ray of light amidst the gloom of Gormenghast in Titus Groan, Fuchsia, since her father’s death, has become a more melancholy character, and her embrace of Steerpike, and subsequent disappointment, drives her further into despair, and increases Titus’s hatred, setting the stage for their inevitable confrontation.

Their final climactic battle might seem to be the sort that ends so many fantasy novels, as the forces of good and evil collide. But Gormenghast is by no means a typical fantasy, and the “battle between good and evil” is not what Peake is interested in. In fact, Steerpike and Titus have much in common—both are rebels from the perspective of Gormenghast. Steerpike, born at the lowest level of Gormenghast’s society, destined to serve in the kitchens (which really are in the lowest levels of the castle), uses intelligence and guile to work his way into a position of power within a world whose every tradition would try to prevent his ascent. In Titus Groan, Steerpike might even be seen as heroic, though by the end of that novel, his willingness to hurt the characters we have come to care about leads the reader to withdraw sympathy. In Gormenghast, there is no doubt that Steerpike is portrayed as evil, but there is always the lingering realization that this evil has arisen as a response to the rigid society of Gormenghast, which allows no productive outlet for an ambitious, intelligent young man. Of course, this doesn’t excuse Steerpike’s actions, but it raises interesting questions. To what extent is a society responsible for creating its criminals?

Titus, put into the position of fighting Steerpike, is also a rebel. As he gets older, he increasingly chafes against the role that Gormenghast requires of him, drawn by the example of a mysterious wild child he glimpses during his roaming of the forest outside the castle, living in absolute freedom on the other side of the walls of Gormenghast. The connection is deepened by the fact that this almost supernatural child is the daughter of Titus’s nursemaid, exiled by the Bright Carvers who live outside the castle, whose roles are just as carefully constrained by ritual as those within, and who have no place for an illegitimate child in their midst. Titus longs to explore the world outside Gormenghast, and has no interest in playing his assigned role, and this makes him just as dangerous to the castle’s traditions as Steerpike. While Steerpike’s rebellion is from within, Titus’s expresses itself in the need to escape. That the two must come into conflict with each other is the result of being born into social positions neither of them asked for.

Titus, put into the position of fighting Steerpike, is also a rebel. As he gets older, he increasingly chafes against the role that Gormenghast requires of him, drawn by the example of a mysterious wild child he glimpses during his roaming of the forest outside the castle, living in absolute freedom on the other side of the walls of Gormenghast. The connection is deepened by the fact that this almost supernatural child is the daughter of Titus’s nursemaid, exiled by the Bright Carvers who live outside the castle, whose roles are just as carefully constrained by ritual as those within, and who have no place for an illegitimate child in their midst. Titus longs to explore the world outside Gormenghast, and has no interest in playing his assigned role, and this makes him just as dangerous to the castle’s traditions as Steerpike. While Steerpike’s rebellion is from within, Titus’s expresses itself in the need to escape. That the two must come into conflict with each other is the result of being born into social positions neither of them asked for.

In contrast to the drama of these two characters and their progress toward the novel’s climax, Peake also presents readers with the everyday life of those who would not think of resisting the status quo, and his often humorous character portraits are one of the major attractions of the novel. His portrayals of Titus’s schoolteachers area hilarious highlight. Of the ill-fated headmaster Deadyawn, who is transported about the school grounds in a wheeled high chair pushed by “a tiny freckled man”, Peake writes:

It was thought that he had genius, if only because he had been able to delegate his duties in so intricate a way that there was never any need for him to do anything at all. His signature, which was necessary from time to time at the end of long notices which no one read, was always faked, and even the ingenious system of delegation whereon his greatness rested was itself worked out by another.

It was thought that he had genius, if only because he had been able to delegate his duties in so intricate a way that there was never any need for him to do anything at all. His signature, which was necessary from time to time at the end of long notices which no one read, was always faked, and even the ingenious system of delegation whereon his greatness rested was itself worked out by another.

In particular, much of the first half of the book is occupied with the odd courtship of Bellgrove, the school headmaster who succeeds Deadyawn (and therein lies a tale), and Irma Prunesquallor, the doctor’s dim, earnest, but self-deluded sister. (“Every muscle in her face was pulling its weight. Not all of them knew in which direction to pull, but their common enthusiasm was formidable. It was as though all her previous contortions were mere rehearsals.”) Just as roles within the castle are unquestioned, both have the idea that marriage should be part of their personal roles. Their meeting, falling and love, and marriage take place as much in their own minds as in their actual lives, and the fact that the outcome is not what either expected comes as no surprise to the reader, yet they cannot deny their strong desire to do what is expected of them. The humorous scenes and stories of everyday life in the castle may seem to distract from the main plot and hurt the novel’s structure, but they are important in that they help us understand what Titus and Steerpike are rebelling against. These scenes are also the source of much of the humor and entertainment in the novel, in contrast again to the rather grim progress of Steerpike and the castle’s fierce resistance.

Peake is an exemplar of the “cult” writer—those who do not achieve the popular success of a Tolkien, Jordan, or Martin, but whose admirers are fiercely loyal. His work has been a major influence on authors like Michael Moorcock and Neil Gaiman, though, as mentioned at the beginning of this essay, such influence does not come by way of imitation. And for many critics, Peake’s work eclipses that of his better known contemporaries. In his Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels, critic David Pringle decides to date the beginning of the “modern fantasy” era in 1946, since this allows Titus Groan (“one of the greatest fantasy novels in the language”) to lead off the volume. And the last word goes to critic John Clute, in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, who writes that the Gormenghast sequence is “the most intensely visual fantasy ever written. It is like a gothic fantasy stripped of all plot accretions, of all intrusions of the supernatural, until only impacted ambience remains. It is something of a masterpiece.”

Full Details

Full Details

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.