Forays into Fantasy: Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, in an attempt to understand the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Gormenghast was released in 1950, the same year as The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Lord of the Rings would soon follow. These latter two works may be seen as the defining fantasies of the second half of the twentieth century, altering the landscape of the field, popularizing the secondary world fantasy and setting the stage for the advent of fantasy as a commercial genre in the late 1960s. As well as developing an enduring popularity that continues into the present, these books (especially, or course, The Lord of the Rings) have been more influential on fantasy literature than anything since. And yet, though it is not read as widely as these two contemporaries, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, conceived in that same post-war period in England, seem to me to be just as important. Unlike Tolkien and Lewis, Peake has not inspired hordes of imitators or greatly influenced the direction of commercial fantasy. The influence of Mervyn Peake could not be based on imitating the plot structure or external trappings of his creation—the books are too idiosyncratic for that to be a temptation. Rather, the strand of Peake’s influence can be seen in those writers of modern fantasy who have rejected the commercial allure of Tolkien-like epic fantasy in order to pursue their own personal fantastic visions, and those for whom character, theme, and style are at least as important as plot and exterior world-building.

Gormenghast was released in 1950, the same year as The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Lord of the Rings would soon follow. These latter two works may be seen as the defining fantasies of the second half of the twentieth century, altering the landscape of the field, popularizing the secondary world fantasy and setting the stage for the advent of fantasy as a commercial genre in the late 1960s. As well as developing an enduring popularity that continues into the present, these books (especially, or course, The Lord of the Rings) have been more influential on fantasy literature than anything since. And yet, though it is not read as widely as these two contemporaries, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, conceived in that same post-war period in England, seem to me to be just as important. Unlike Tolkien and Lewis, Peake has not inspired hordes of imitators or greatly influenced the direction of commercial fantasy. The influence of Mervyn Peake could not be based on imitating the plot structure or external trappings of his creation—the books are too idiosyncratic for that to be a temptation. Rather, the strand of Peake’s influence can be seen in those writers of modern fantasy who have rejected the commercial allure of Tolkien-like epic fantasy in order to pursue their own personal fantastic visions, and those for whom character, theme, and style are at least as important as plot and exterior world-building.

This is not to say that world-building is not important in Peake’s works, but it is not of the sort that epic fantasy fans will be looking for. The inhabitants of Gormenghast can only be defined in relation to the environment their forebears created for them, and this environment—Gormenghast castle and it’s immediate natural surroundings—is described in such visual terms that the setting is evoked in a way rarely achieved, and this setting is arguably more interesting than any individual character. But this world-building is focused interiorly on the isolated castle. There’s no need for a map to track the characters’ progress, and the outside world is never described in the first two Gormenghast novels. This aspect adds to the strangeness and dislocation created by Peake’s writing, since the reader knows nothing of the larger world in which Gormenghast is situated. The result is a strange combination of dislocation and concreteness. We do not know where or when Gormenghast exists, yet it comes to seem entirely real on its own terms. The concreteness of the castle setting is further enhanced by the fact that Gormenghast seemingly has not changed for centuries, possibly millennia (aside from a slow deterioration), and it is this fact that creates the conflict that first become apparent in the first Gormenghast novel, Titus Groan (1946, see previous post), and comes to a head in the second, Gormenghast (1950).

Forays into Fantasy: The Castle of Otranto, the Gothic Novel and the Origins of Fantasy

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

As my interest in science fiction was revived over the last couple of years, and I decided to expand my reading into fantasy as well, I went in search of context. Looking for a guide to some superior and important examples of fantasy, beyond the usual suspects, I pulled David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels off the shelf (and examples of some of these novels will continue to show up in this series of posts), but Pringle begins in 1946, and I wanted to start at the beginning. Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, published in 1988, starts in the eighteenth century. Specifically, the first book listed is Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) — no surprise there. The other three examples from the 1700s, though, I had never heard of before: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, Vathek by William Beckford, and The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis. Upon reading Cawthorn and Moorcock’s essays, it became clear that these were all examples of early Gothic novels, which make up one of the earliest strands of the fantasy genre.

As my interest in science fiction was revived over the last couple of years, and I decided to expand my reading into fantasy as well, I went in search of context. Looking for a guide to some superior and important examples of fantasy, beyond the usual suspects, I pulled David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels off the shelf (and examples of some of these novels will continue to show up in this series of posts), but Pringle begins in 1946, and I wanted to start at the beginning. Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, published in 1988, starts in the eighteenth century. Specifically, the first book listed is Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) — no surprise there. The other three examples from the 1700s, though, I had never heard of before: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, Vathek by William Beckford, and The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis. Upon reading Cawthorn and Moorcock’s essays, it became clear that these were all examples of early Gothic novels, which make up one of the earliest strands of the fantasy genre.

So, did fantasy as a genre really begin in the 1700s (clearly, there was fantastic literature prior to that), and what role did these Gothic novels play in those beginnings? During this eighteenth century, poets and philosophers debated the nature of imagination, and there was a new and rising view that the imagination was not merely a repository of memory and observation, but was a faculty capable of the visionary illumination of the unknown, as Samuel Coleridge and William Blake tried to do in their poetry. In literature, these ideas led to the ongoing distinction between the realistic and the fantastic. As Gary K. Wolfe writes in “Fantasy from Dryden to Dunsany,” in The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature (2012):

“The modern fantasy novel, and to an arguable extent the modern novel itself, is in part an outgrowth of this debate. While we can reasonably argue that the fantastic in the broadest sense had been a dominant characteristic of most world literature for centuries prior to the rise of the novel, we can also begin to discern that the fantasy genre may well have had its origins in these eighteenth- and nineteenth-century discussions of fancy vs. imagination, history vs. romance…”

In particular, Wolfe sees the fantasy genre as arising from three sources during the 1700s and 1800s: “private history” novels such as Robinson Crusoe, a revival of interest in old folk tales and fairy tales, and the vogue for Gothic novels, all three of which required the use of imagination to envision what we now think of as “the fantastic.”

Where, then, did this Gothic strand of literature arise from, and what does it entail? Our story begins during the latter stages of the Roman Empire, when the Goths pillaged their way south from Scandinavia, ultimately sacking Rome in 410. After gaining control of the Italian peninsula, they eventually lost power later in the Middle Ages, after sundry violent run-ins with the Huns, the Franks, and the Moors. Due to its association with the decline of the Classical world, the term “Gothic” came into use during the 1500s as a pejorative term for a medieval style in art and architecture, from the twelfth — through the sixteenth — centuries, which was considered during the Renaissance to be ugly and barbaric when compared to the Classical art and architecture it supplanted. It is best represented by the intricate and sculpturally adorned Medieval cathedrals with their soaring pointed arches, which took advantage of advances in structural design to achieve previously unprecedented height, with correspondingly tall windows and, of course, lots of gargoyles.

Where, then, did this Gothic strand of literature arise from, and what does it entail? Our story begins during the latter stages of the Roman Empire, when the Goths pillaged their way south from Scandinavia, ultimately sacking Rome in 410. After gaining control of the Italian peninsula, they eventually lost power later in the Middle Ages, after sundry violent run-ins with the Huns, the Franks, and the Moors. Due to its association with the decline of the Classical world, the term “Gothic” came into use during the 1500s as a pejorative term for a medieval style in art and architecture, from the twelfth — through the sixteenth — centuries, which was considered during the Renaissance to be ugly and barbaric when compared to the Classical art and architecture it supplanted. It is best represented by the intricate and sculpturally adorned Medieval cathedrals with their soaring pointed arches, which took advantage of advances in structural design to achieve previously unprecedented height, with correspondingly tall windows and, of course, lots of gargoyles.

As pointed out by Adam Roberts in his essay on “Gothic and Horror Fiction” also in The Cambridge Companion, by the time the term “Gothic” was first used to describe a form of literature, in the mid-eighteenth century, its “primary signification… was that of barbarous anti-enlightenment.” At the same time, a revival of interest in Gothic aesthetics would result in the term becoming more complimentary in the eyes of those who began to bring the now old-fashioned medieval styles back into fashion. Among these was Horace Walpole, who rebuilt his London mansion in what he considered to be a “Gothic” style, and wrote what is generally agreed to be the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto: A Story, published in 1764. (Subsequent editions would be subtitled A Gothic Story.)

Walpole originally published The Castle of Otranto under a pseudonym, claiming in the preface that it was a translation of a recently discovered manuscript printed in 1529 and most likely written between 1095 and 1243, thus pretending to establish it as an actual work of the Middle Ages. He speculates that it was written by a priest in order to “avail himself of his abilities as an author to confirm the populace in their ancient errors and superstitions” at a time when such superstitions were being challenged by the Italian intelligentsia. Although presented by the translator as a mere entertainment:

“Some apology for it is necessary. Miracles, visions, necromancy, dreams, and other preternatural events, are exploded now even from romances. That was not the case when our author wrote; much less when the story itself is supposed to have happened. Belief in every kind of prodigy was so established in those dark ages, that an author would not be faithful to the manners of the times, who should omit all mention of them. He is not bound to believe them himself, but he must represent his actors as believing them. If this air of the miraculous is excused, the reader will find nothing else unworthy of his perusal. Allow the possibility of the facts, and all the actors comport themselves as persons would do in their situation… Terror, the author’s principal engine, prevents the story from ever languishing; and it is so often contrasted by pity, that the mind is kept up in a constant vicissitude of interesting passions.”

Clearly, Walpole was aware of the debate over the role of imagination in literature described above by Wolfe, and was attempting to combine the virtues of the modern novel with the fanciful content of ancient stories and myths. Ironically, while claiming to apologize to the reader for the old-fashioned fantastical elements in the story, what Walpole was really doing, by bringing these elements into a novel, was to create something entirely new. In the Middle Ages, people really were superstitious, and such stories would not have been considered “fantastic” in the modern sense. By the 1700s, by which time the Enlightenment had banished superstition from the educated mind, bringing back the fantastic required a new use of imagination for both writers and their audience.

Clearly, people were ready for it. In a popular and commercial sense, his experiment was very successful, unleashing a sea of imitators. Despite Walpole’s apology for it, it is that very “air of the miraculous” that makes the novel intriguing. The plot itself is quite ludicrous, but individual incidents, and the overall mood, keep things interesting. Manfred, lord of the Castle of Otranto, while overseeing the wedding of his sickly son Conrad to Isabella, is shocked and dismayed when a giant helmet appears and crushes Conrad to death, leaving Manfred without an heir. The enormous helmet is otherwise identical to that once worn by Alfonso the Good, who is supposed to have granted the castle to Manfred’s grandfather many years before. Clearly concerned about the implications of this strange event, and determined to maintain his family’s succession, he announces his intention to divorce his wife Hippolita, who has been incapable of providing him with another son, and marry Isabella himself. Neither woman is pleased. Isabella escapes with the help of Theodore, whom Manfred sentences to death. Chasing Theodore and Isabella into the vaults beneath the castle, Manfred encounters an apparition of his grandfather, as well as manifestations of giant armored body parts and weapons, presumably arising from the same source as the helmet. As Manfred had feared, these visions herald the fulfillment of a prophecy that foretold the end of his family’s usurpation of the castle, and the return of its rightful heir, who turns out to be Theodore. Isabella ends up Queen of the castle after all.

Clearly, people were ready for it. In a popular and commercial sense, his experiment was very successful, unleashing a sea of imitators. Despite Walpole’s apology for it, it is that very “air of the miraculous” that makes the novel intriguing. The plot itself is quite ludicrous, but individual incidents, and the overall mood, keep things interesting. Manfred, lord of the Castle of Otranto, while overseeing the wedding of his sickly son Conrad to Isabella, is shocked and dismayed when a giant helmet appears and crushes Conrad to death, leaving Manfred without an heir. The enormous helmet is otherwise identical to that once worn by Alfonso the Good, who is supposed to have granted the castle to Manfred’s grandfather many years before. Clearly concerned about the implications of this strange event, and determined to maintain his family’s succession, he announces his intention to divorce his wife Hippolita, who has been incapable of providing him with another son, and marry Isabella himself. Neither woman is pleased. Isabella escapes with the help of Theodore, whom Manfred sentences to death. Chasing Theodore and Isabella into the vaults beneath the castle, Manfred encounters an apparition of his grandfather, as well as manifestations of giant armored body parts and weapons, presumably arising from the same source as the helmet. As Manfred had feared, these visions herald the fulfillment of a prophecy that foretold the end of his family’s usurpation of the castle, and the return of its rightful heir, who turns out to be Theodore. Isabella ends up Queen of the castle after all.

The genre ushered in by Walpole’s story remained very popular until about 1820, and continued to evolve thereafter (think of Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights, Dracula, and Rebecca). Very few of the novels from the original flowering of the Gothic are still read, but they represented an unleashing of imaginative literature that would ultimately lead to the development of the modern genres of horror (which still maintains an explicitly gothic strand), fantasy, and even science fiction, whose readers are often looking for the same “sense of wonder” as was the original audience for gothic fiction.

The characteristic feeling evoked by the Gothic story is the combination of the familiar and the foreign — the simultaneous attraction and repulsion that Freud wrote about as “the uncanny.” This characteristic of the Gothic has to do with the mood rather than the well-known trappings of the stories — the feeling of mysteriousness, that there are things happening that we can’t quite understand and that may ultimately remain obscure; that important realizations are just out of reach in the shadows and gloom. The reader wants to find out what horrors (usually evils from the past returning to haunt the present) underlie the events in the story, but at the same time is afraid to find out.

The typical elements of the settings in which these strange stories play out have become iconic. As Adam Roberts explains:

“In Otranto we find, in nascent form, many of the props and conventions that were to reappear in the scores of novels published at the height of the Gothic vogue…: moody atmospherics, picturesque and sublime scenery, darkness, buried crimes (especially murderous and incestuous crimes) revealed, and most of all a spectral supernatural focus. Many imitators tried to follow Walpole’s commercial success by littering their novels with similar props, settings and conventions — the haunted castle, the night-time graveyard, the Byronic villain and so on,”

But the elements that make the works successful are not these outward trappings, but rather their ability to invoke the uncanny and the transgressive, and to fire the reader’s imagination.

But the elements that make the works successful are not these outward trappings, but rather their ability to invoke the uncanny and the transgressive, and to fire the reader’s imagination.

As for Otranto in particular, it is the first, but not the very best. Fantasy readers today will have no problem with the fantastic elements, but may struggle with the improbable plot twists, many of which hinge on mistaken or hidden identity, and with the overwrought dialogue. Those willing to make allowances, however, will be carried along by the onrushing events and the feverish intensity of the characters’ emotions and actions, until the situation they are caught up in is finally resolved. These events, manifested through supernatural interventions into the real world, were precipitated by past injustice, a pattern which will play out again in subsequent Gothic novels, often within some variation on Walpole’s shadowy castle and subterranean vaults, literary images that have never ceased to haunt readers of the fantastic.

Next: More early Gothic novels will be reviewed in a future post, but up next is a 1949 American fantasy novel set in a land where stories are real: Silverlock by John Myers Myers.

Titas Groan: Favorite Fantasy

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. Check out his review of one of the all-time fantasy classics.

In Titus Groan, Mervyn Peake created a masterwork of alternate reality, unlike anything else in literature. For good reason, David Pringle begins the date range for his Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels in 1946, so that this can be the first entry on his list. It achieves its unique vision with a combination of vivid setting and characterization, both built up with a luxurious edifice of language that is a joy to read.

In Titus Groan, Mervyn Peake created a masterwork of alternate reality, unlike anything else in literature. For good reason, David Pringle begins the date range for his Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels in 1946, so that this can be the first entry on his list. It achieves its unique vision with a combination of vivid setting and characterization, both built up with a luxurious edifice of language that is a joy to read.

Titus Groan is the first novel of Peake’s Gormenghast Series, of which three novels were published during his lifetime, with other planned volumes never completed. His widow’s completion of the fourth novel, Titus Awakes, was published in 2011.

It’s a difficult novel to characterize in terms of genre definition. Though generally categorized as fantasy, it doesn’t fit neatly into the category. It takes place in a fantasy setting, in the sense that it is a place and/or time that is nonexistent, yet nothing literally “fantastic” happens in the novel. There are no explicit magical or supernatural elements in the story. The building up of the sense of place is one of the great enjoyments of the novel, so any summation will fail to do it justice, but the words that come to mind in describing Gormenghast, the castle setting, are “weight” and “tradition.” The characters have Dickensian names like Sepulchrave, Prunesquallor, and Swelter, and there are other echoes of British culture, which the setting may in part be a commentary on.

Titus, born at the beginning of the story, is destined to be the 77th Earl of Gormenghast, implying (though it is not made explicit) a 2,000-year dynasty. Throughout this time (at least), the castle and the surrounding lands have observed strict and unchanging rituals, the specifics of which are nonsensical (and are humorous in their description), but which all the characters agree on the importance of. Though such literal speculation is probably pointless, it’s even possible that the setting could be in the far future, after humanity has lost most of its technology and returned to a sort of feudal existence even more rigid than that of the Middle Ages. (It would not surprise me if Peake was an influence on Jack Vance’s Dying Earth.)

The world of Gormenghast has the “Dark Ages” feel beloved of fantasy writers, but there are oddities, such as Dr. Prunesquallor’s knowledge of anatomy and chemistry, and the fact that characters drink coffee, that seem anachronistic. Despite the lack of change, there is also a sense of decline. The reasons for the rituals are forgotten; sections of the castle have not been visited for centuries; the hereditary leaders are subject to imbecility and mental illness; only Steerpike, the outsider whose story provides the primary plot of the novel, notices details of his surroundings that the other characters give no thought to.

In this world, change is considered to be the greatest evil. Just as Titus is born to continue carrying on the traditions, Steerpike is introduced as an agent of change. There are several ways to interpret the role of Steerpike in the story. He is born as a kitchen laborer, destined to drudgery in the lowest level of the castle, but is determined to find a way out, slowly insinuating himself into the lives of the high-born characters by finding ways of making himself indispensable to them. Is he a working-class revolutionary looking to bring equality to this society (a view he espouses at times), or rather a sort of infection rising up from the depths of the castle to destroy the lives of the other characters (a reading consistent with his actions)? At times, we sympathize with Steerpike, and admire his intelligence and willingness to act, in strong contrast to the ritual-bound and seemingly lifeless existence of the other characters.

In this world, change is considered to be the greatest evil. Just as Titus is born to continue carrying on the traditions, Steerpike is introduced as an agent of change. There are several ways to interpret the role of Steerpike in the story. He is born as a kitchen laborer, destined to drudgery in the lowest level of the castle, but is determined to find a way out, slowly insinuating himself into the lives of the high-born characters by finding ways of making himself indispensable to them. Is he a working-class revolutionary looking to bring equality to this society (a view he espouses at times), or rather a sort of infection rising up from the depths of the castle to destroy the lives of the other characters (a reading consistent with his actions)? At times, we sympathize with Steerpike, and admire his intelligence and willingness to act, in strong contrast to the ritual-bound and seemingly lifeless existence of the other characters.

On the other hand, we also sympathize with the Earl’s family. They are not evil, and are just as much bound by tradition as the servants, being forced to participate in endless boring rituals, without any other purpose in life. As a result, Lord Sepulchrave (the 76th Earl) retreats into his library and is continually depressed, his wife Gertrude retreats from the society of other people and responds emotionally only to pets, and their teenage daughter Fuchsia wanders mentally and physically in search of some sort of happiness or enervation that seems out of reach. We might approve of a “shaking up” of this world, but Steerpike revels not just in change but in destruction, setting in motion a series of events that eventually erupt into violence, and his motives seem entirely selfish.

It is tempting to see an allegory. Is Gormenghast meant to represent the post-War British society in which Peake lived, its class system resisting the modernity brought on by the rapid historical changes resulting from world war and the decline of Britain’s empire? If so, it could be that Peake was both criticizing this world and regretting its destruction. This ambiguity of reaction to historical change is not atypical, as evidenced by the impulses toward both conservatism and liberalism characteristic of modern societies. An unchanging society is stifling to individuals, but change is painful to those accustomed to (especially if they are invested in) the status quo.

Part of the genius of Titus Groan, however, is that readers with no comprehension of (or interest in) the potential subtext, if they are lovers of good writing, fictional world-building, and vivid characterization, will still see the novel as a classic of fantasy. Peake immerses us in a world that is both alien and familiar. Each sentence adds a brick to the edifice of both Gormenghast and the novel that describes it. The word “classic” may be overused, but I’m using it here!

Month of Horrors: End of Month Wrap-Up

Today isn’t just Halloween, it’s also the closing day of WWEnd’s Month of Horrors, our 31-day celebration of the Horror genre in conjunction with adding this genre to the site. We’ve decided to wrap up the festivities with a dialogue between Rico and me about the genre. We may not be the biggest Horror aficionados in the world, but we both love literature, and I think we are both curious to see how it fits in the pantheon of genres, and especially how it relates to Science Fiction and Fantasy, the long-time staples of the WWEnd site.

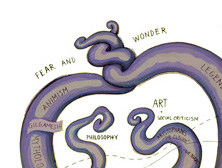

Jonathan: Ward Shelley in his infographic links genre fiction back into the primal emotions of Fear and Wonder. Arguably the Horror genre is far more about Fear than Wonder, though it often has its fair share of both. H. P. Lovecraft, of all people, occasionally wrote lyrically beautiful stories like “The White Ship” which were filled with wonder. But despite its primal roots, I don’t know of any previous body of literature that has focused so intently on the emotion of fear. In some ways, it reminds me of amusement park rides, which are built almost entirely to give the riders a thrill or a scare, the false feeling that their lives are in imminent physical danger even though everything is perfectly under control. I’ve often wondered if the thrill of fear is the primary draw for horror readers, if they are wanting to feel a “safe danger” like that of the amusement park ride. In other cases I suspect that the genre is a way of dramatically expounding on a philosophical or theological belief about the nature of the universe, the human condition, and the relationship between humanity and whatever cosmic powers might be. Do you have any thoughts on the genre from this perspective? Certainly I doubt that we will be able to fully unravel the mystery of any genre’s attraction—even Science Fiction is often more confounding than captivating to me—but I admire it if only as an outsider.

Jonathan: Ward Shelley in his infographic links genre fiction back into the primal emotions of Fear and Wonder. Arguably the Horror genre is far more about Fear than Wonder, though it often has its fair share of both. H. P. Lovecraft, of all people, occasionally wrote lyrically beautiful stories like “The White Ship” which were filled with wonder. But despite its primal roots, I don’t know of any previous body of literature that has focused so intently on the emotion of fear. In some ways, it reminds me of amusement park rides, which are built almost entirely to give the riders a thrill or a scare, the false feeling that their lives are in imminent physical danger even though everything is perfectly under control. I’ve often wondered if the thrill of fear is the primary draw for horror readers, if they are wanting to feel a “safe danger” like that of the amusement park ride. In other cases I suspect that the genre is a way of dramatically expounding on a philosophical or theological belief about the nature of the universe, the human condition, and the relationship between humanity and whatever cosmic powers might be. Do you have any thoughts on the genre from this perspective? Certainly I doubt that we will be able to fully unravel the mystery of any genre’s attraction—even Science Fiction is often more confounding than captivating to me—but I admire it if only as an outsider.

Rico: Horror does seem to have older roots than other genres. Whether it’s Odysseus trapped between the monster (Scylla) and a gaping nothingness (Charybdis), Hercules battling a hydra, or Jason facing the harpies, even the ancient Greeks felt the need for monstrous yarns. Lovecraft said this was because fear is our oldest emotion, especially fear of the unknown. In a lot of ways, it sort of drives us to find out what it is that scares us, so we can conquer it. Fear, then, is not so different from wonder.

Rico: Horror does seem to have older roots than other genres. Whether it’s Odysseus trapped between the monster (Scylla) and a gaping nothingness (Charybdis), Hercules battling a hydra, or Jason facing the harpies, even the ancient Greeks felt the need for monstrous yarns. Lovecraft said this was because fear is our oldest emotion, especially fear of the unknown. In a lot of ways, it sort of drives us to find out what it is that scares us, so we can conquer it. Fear, then, is not so different from wonder.

As to why horror is so attractive, however, we need a different explanation. Maybe one clue can be found in physiology. Sartre once observed that the symptoms of fear (dilation of the pupils, elevated heart rate, perspiration) also happen to occur when one falls in love. Two completely different conditions elicit the same bodily reactions. Because fear is so primal, it might be easier to frighten a reader than to make him/her fall in love. If the trill of a good scare gets me flushed in a way that is so love-like, why wouldn’t I enjoy it?

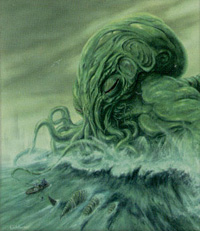

Jonathan: You mentioned both the Lovecraft and the ancient Greeks, but there’s a world of difference between the way each would approach a horrific tale. The Greeks had stories of monsters like Medusa and Typhon which, on the surface, are very similar to monsters like Lovecraft’s Cthulu, but while the Greek monsters might eat the occasional passerby and even level a mountain or two, Olympus could never truly lose the world to these monsters. Cthulu, on the other hand, will inevitably rise from the watery deeps to darken the sky and devour mankind. There’s the horror that is finite and destructible, like the Chimera and the Hydra, and then there’s the horror that devours not only people but hope. A classical tale of horror might end badly for some people, but it will also end with the sun still shining and regular people living their lives. A modern horror tale will often end with the emotional and psychological devastation of the protagonist, whose beliefs about the stability of the world have been crushed.

Jonathan: You mentioned both the Lovecraft and the ancient Greeks, but there’s a world of difference between the way each would approach a horrific tale. The Greeks had stories of monsters like Medusa and Typhon which, on the surface, are very similar to monsters like Lovecraft’s Cthulu, but while the Greek monsters might eat the occasional passerby and even level a mountain or two, Olympus could never truly lose the world to these monsters. Cthulu, on the other hand, will inevitably rise from the watery deeps to darken the sky and devour mankind. There’s the horror that is finite and destructible, like the Chimera and the Hydra, and then there’s the horror that devours not only people but hope. A classical tale of horror might end badly for some people, but it will also end with the sun still shining and regular people living their lives. A modern horror tale will often end with the emotional and psychological devastation of the protagonist, whose beliefs about the stability of the world have been crushed.

So while there is a kind of pleasurable (even love-like) thrill that can come from a frightening story, I don’t know that the Lovecraftian sort of total despair offers the same pleasure. David Hume once wrote about the stage tragedies of his day: “What [can be] so disagreeable as the dismal, gloomy, disastrous stories with which melancholy people entertain their companions?  The uneasy passion being there raised alone, unaccompanied with any spirit, genius, or eloquence, conveys a pure uneasiness, and is attended with nothing that can soften it into pleasure or satisfaction.” Do you think that modern horror perhaps offers the taste of that thrill without the pleasure, or am I being too harsh on it?

The uneasy passion being there raised alone, unaccompanied with any spirit, genius, or eloquence, conveys a pure uneasiness, and is attended with nothing that can soften it into pleasure or satisfaction.” Do you think that modern horror perhaps offers the taste of that thrill without the pleasure, or am I being too harsh on it?

Rico: I agree that there is a difference between the Greek stories and Lovecraft, but Lovecraft doesn’t define the genre. The world is still intact when the tell-tale heart stops beating, when the vampire finally gets staked, and when the last alien is flushed into space by Sigourney Weaver. Lovecraftian horror, it seems to me, is a special extremist sub genre. Of course, even it doesn’t find the world in tatters (there’d be no story if Hastur or Cthulu ever crossed over). It’s the threat of obliteration that makes the story exciting. In that sense, the Lovecraftian world really does share something in common with Odysseus and his men hovering on the brink of Charybdis, yet not quite falling in.

Also, although it’s true that the Olympic gods may not lose the world (well, there is one time, in the Iliad, when the Fates tell Zeus that he may defy them to save Troy, but that the cosmos would fall into chaos as a result), but humans certainly can lose their world. I’m thinking of Hecuba, for whom there can be no solace. Niobi (“all tears”) comes to mind. As in Lovecraft’s world, the gods take away everything.

Perhaps a better ancient analogue to Cthulu is Vishnu, the Hindu god whom Oppenheimer quoted as he reflected upon the nuclear horror he helped to create: “Now, I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

Perhaps a better ancient analogue to Cthulu is Vishnu, the Hindu god whom Oppenheimer quoted as he reflected upon the nuclear horror he helped to create: “Now, I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

Jonathan: Fair enough. In addition to the classical and modern horror narratives, it’s educational to look at the Medieval/Christian stories that most closely match the genre. Medieval poets loved singing about bizarrely chimeric beasts in addition to the demons and occult practitioners who frequently tormented the innocent. Meanwhile, Dante’s Inferno explored the greatest horror imaginable: everlasting damnation and torment. It’s a particularly interesting sort of horror, though, in that the one experiencing its pains has brought them upon himself. (Those in Dante’s version of Hell who are there by no vice of their own, like the unbaptized infants and the virtuous pagans, suffer no external pains.) When Dante tours the underworld, he is not witnessing the caprices of a cruel god, but the wasted lives of those who refused to do good and now suffer the consequences. The Medieval vision of Hell managed to combine the classical vision of celestial permanence and beauty with the all-consuming despair of a Lovecraftian apocalypse, as it’s inscribed on Hell’s doors: “Justice caused my high Architect to move… / The highest Wisdom, and the primal Love … / Abandon all hope you who enter here” (trans. Anthony Esolen).

To my mind, the best of the Horror genre is that which manages to keep both aspects of reality in play. When the balance tips entirely towards Tragedy (so to speak) or entirely in favor of Comedy, one feels that the poet or novelist isn’t being entirely honest about the way things are. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is a magnificently-written novel, but it is arguably stuck in an emotional rut of bleak despair. As a counterpoint, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings saga is a work which manages to drink the cup of futility to its last drop, without losing hope.

To my mind, the best of the Horror genre is that which manages to keep both aspects of reality in play. When the balance tips entirely towards Tragedy (so to speak) or entirely in favor of Comedy, one feels that the poet or novelist isn’t being entirely honest about the way things are. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is a magnificently-written novel, but it is arguably stuck in an emotional rut of bleak despair. As a counterpoint, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings saga is a work which manages to drink the cup of futility to its last drop, without losing hope.

Rich: That, it seems, is very much in keeping with Hallowe’en, which is a sort of twilight between the despair of loss (death) and the joy of All Saints Day (and All Souls Day, on November 2). The fact that today is an ’eve (and not the day itself) suggests a sort of lack of completion. We go out begging (trick or treating), perhaps because we lack something we want. All Hallows Evening is a darker anticipation of something miraculous, the feast day of every saint that ever was. There is, nay, there must be some sort of hope at the end of despair.

Jonathan: I’ll close simply by noting a small handful of Horror books I still plan to read, since I still feel inadequately-read in the genre. The Monk, The Castle of Otranto, and Melmoth the Wanderer are all at the top of my list as Gothic subgenre works; despite my recent bad experience with Nathaniel Hawthorne’s attempt at Gothic fiction, I still want to give it a try. I might also crack open some children’s horror with Neil Gaiman’s Coraline and The Graveyard Book. Joe Hill’s Horns is on the list, but a little further down.

What say you, Rico?

Rico: I’m likely to be more behind in my reading than you. It seems that much of the horror tradition is American, and may have roots not just in the English Gothic Novel, but also in the constant low-grade terror of North America’s indigenous population. Jung believed that tales of demonic possession waned in the American mind as rationalism took hold, and was replaced by stories of Indian abductions (and that those stories, in the 20th century turned into alien abductions!). This gets back to your idea of the unknown, and it makes me want to read all three kinds of "abduction" stories. The stories of Captain John Smith may sound more like a good old adventure story than horror, but it was a source of much anxiety to its readers in early America, who were more than familiar with the gruesome legacy of Roanoke. I also have an interest in the more recent accounts of body snatching: One such story is The Exorcist, which William Peter Blatty did not intend to be a horror novel at all. Another is I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, which has inspired how many movies? If Jung were writing today, he might say that zombies are the latest incarnation of the abduction myth, and boy is it having its heyday, today.

Rico: I’m likely to be more behind in my reading than you. It seems that much of the horror tradition is American, and may have roots not just in the English Gothic Novel, but also in the constant low-grade terror of North America’s indigenous population. Jung believed that tales of demonic possession waned in the American mind as rationalism took hold, and was replaced by stories of Indian abductions (and that those stories, in the 20th century turned into alien abductions!). This gets back to your idea of the unknown, and it makes me want to read all three kinds of "abduction" stories. The stories of Captain John Smith may sound more like a good old adventure story than horror, but it was a source of much anxiety to its readers in early America, who were more than familiar with the gruesome legacy of Roanoke. I also have an interest in the more recent accounts of body snatching: One such story is The Exorcist, which William Peter Blatty did not intend to be a horror novel at all. Another is I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, which has inspired how many movies? If Jung were writing today, he might say that zombies are the latest incarnation of the abduction myth, and boy is it having its heyday, today.

So that wraps up our Worlds Without End Month of Horrors! We hope you’ve all enjoyed our exploration of the Horror genre during the month of October. Cheery chills, and safe trick-or-treating!

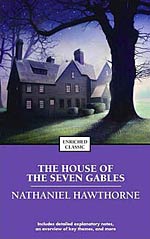

Month of Horrors: The House of the Seven Gables

My introduction to the genre of Gothic Fiction was actually made not by a novel or short story, but by a graphic novel. Unlike the films, Mike Mignola’s Hellboy series is a dark and moody walk through crumbled castles and vine-ridden monasteries, albeit with the occasional gun fight and mad Nazi scientist. Reading it got me in the mood for more of the same, and after some research I discovered that Mignola was playing with a genre that’s been around for quite some time. The addition of the Guardian List brought with it a large selection of Gothic fiction to the WWEnd site, including one novel by an author I was already familiar with, Nathaniel Hawthorne.

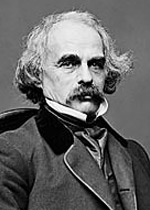

By the time Hawthorne wrote his very popular House of the Seven Gables, he was working within an established genre whose shape and borders had already been established by such writers as Horace Walpole, William Beckford, Matthew Lewis, Charles Maturin, and Edgar Allan Poe. Hawthorne doesn’t disappoint any reader who comes to his novel expecting the same as what these earlier writers provided: ancient aristocratic homes, tyrannous judges, estranged relatives, unspeakable crimes from long ago, one-sided depictions of ancient religious communities, and of course a good haunting. While his book was and is well loved, I’m not sure that I agree with those who love it.

By the time Hawthorne wrote his very popular House of the Seven Gables, he was working within an established genre whose shape and borders had already been established by such writers as Horace Walpole, William Beckford, Matthew Lewis, Charles Maturin, and Edgar Allan Poe. Hawthorne doesn’t disappoint any reader who comes to his novel expecting the same as what these earlier writers provided: ancient aristocratic homes, tyrannous judges, estranged relatives, unspeakable crimes from long ago, one-sided depictions of ancient religious communities, and of course a good haunting. While his book was and is well loved, I’m not sure that I agree with those who love it.

But the fault isn’t, I think, with the genre itself. Even though this is probably the only novel I’ve read that accurately conforms to the classical tropes of the Gothic genre—authors like Bram Stoker and of H.P. Lovecraft wrote books similar to the Gothic, but were developing their own ideas—I still have a strong draw to its peculiar atmosphere. Hawthorne, though, is something of a hack writer, and that harms the novel.  Never content to allow a metaphor to remain implicit, he often spends multiple pages explicating an image he just inserted into the narrative, as though afraid its meaning might possibly pass a reader by. His prose is hardly bad in and of itself, but he can’t stop himself from pointing out his own cleverness. Adding to this weakness is his proclivity for digression, in which he interrupts an ongoing part of the narrative to talk about a character’s or object’s history, or to wax so poetic about something or other that the wax starts dripping all over the place. But for all his literary gurning, Hawthorne leaves a hugely important occurrence at the end of the narrative unexplained even after so much else is revealed. Sometimes one wishes he would shut up and tell the story.

Never content to allow a metaphor to remain implicit, he often spends multiple pages explicating an image he just inserted into the narrative, as though afraid its meaning might possibly pass a reader by. His prose is hardly bad in and of itself, but he can’t stop himself from pointing out his own cleverness. Adding to this weakness is his proclivity for digression, in which he interrupts an ongoing part of the narrative to talk about a character’s or object’s history, or to wax so poetic about something or other that the wax starts dripping all over the place. But for all his literary gurning, Hawthorne leaves a hugely important occurrence at the end of the narrative unexplained even after so much else is revealed. Sometimes one wishes he would shut up and tell the story.

Here’s part of Hawthorne’s description of the eponymous house:

All, as they approached, looked upward at the imposing edifice, which was henceforth to assume its rank among the habitations of mankind. There it rose, a little withdrawn from the line of the street, but in pride, not modesty. Its whole visible exterior was ornamented with quaint figures, conceived in the grotesqueness of a Gothic fancy, and drawn or stamped in the glittering plaster, composed of lime, pebbles, and bits of glass, with which the woodwork of the walls was overspread. On every side the seven gables pointed sharply towards the sky, and presented the aspect of a whole sisterhood of edifices, breathing through the spiracles of one great chimney. The many lattices, with their small, diamond-shaped panes, admitted the sunlight into hall and chamber, while, nevertheless, the second story, projecting far over the base, and itself retiring beneath the third, threw a shadowy and thoughtful gloom into the lower rooms. Carved globes of wood were affixed under the jutting stories. Little spiral rods of iron beautified each of the seven peaks.

Although The House of the Seven Gables is probably not the best example of Gothic fiction, its influence, especially on American horror, cannot be denied. Hawthorne himself is something of an acquired taste, but I know many people who think he’s one of the finest literary figures from early America. Maybe someday I’ll come around to their way of thinking, but it might be a while.

Month of Horrors: The Turn of the Screw

Science Fiction and Fantasy have done a little genre merging of late. Our tech has become a little more fantastic and our magic more technical. Steampunk has crossed over into the mainstream of fandom, kindling a new interest in the 19th century, in particular. Steampunk may be new, but it’s also old. In those heady days of the late 1800s, science fiction was in its infancy, and fantasy wasn’t selling. The hot genre was the ghost story — one of the founding fathers of modern horror.

Science Fiction and Fantasy have done a little genre merging of late. Our tech has become a little more fantastic and our magic more technical. Steampunk has crossed over into the mainstream of fandom, kindling a new interest in the 19th century, in particular. Steampunk may be new, but it’s also old. In those heady days of the late 1800s, science fiction was in its infancy, and fantasy wasn’t selling. The hot genre was the ghost story — one of the founding fathers of modern horror.

One of the great ghost stories is Henry James‘ classic, The Turn of the Screw. Published in 1898, just before the turn the of the century, James’ novel tapped into the freewheeling scientific inquiry of the time. The notion of "spiritual phenomena" was considered scientific and quite legitimate. Many intellectuals of the day professed a belief in ghosts, and séances were all the rage. Yet James approached his ghosts in a way that was as mysterious as the apparitions themselves. The ghosts in The Turn of the Screw are only ever witnessed by one character, and the veracity of her narration is sometimes in doubt. The brother of William James (a famous psychologist), Henry was the first to psychologize the notion of ghosts. The reader is free to suppose the shadowy figures as the delusion of an insane nanny, yet not comfortably. The ghosts themselves never seem to really interact with the world, but, instead, beckon their victims to harm themselves, again leaving room for interpretation. This is, perhaps, why the novella has survived as well as it has (certainly longer than the "science" of spiritualism) — because the ghosts live only in the corner of the reader’s eye. Examine a phenomenon like this too closely, and it vanishes.

The story is the first in a long line of psychological thrillers that have you doubting what you are seeing. Although it isn’t the first of the ghost story genre (Homer, Shakespeare, Dickens all came before), it is possibly the most copied in modern storytelling. After reading The Turn of the Screw, you’ll see subtle homages (intended or unintended) in films like Inception, where the unreliable nature of the human mind is writ large. Life on Mars also comes to mind: "Am I mad, in a coma, or back in time!" The novella even appeared several times in the series Lost, as a clue to eery happenings to come (even after the finale, many Losties were left wondering what was real).

The story is the first in a long line of psychological thrillers that have you doubting what you are seeing. Although it isn’t the first of the ghost story genre (Homer, Shakespeare, Dickens all came before), it is possibly the most copied in modern storytelling. After reading The Turn of the Screw, you’ll see subtle homages (intended or unintended) in films like Inception, where the unreliable nature of the human mind is writ large. Life on Mars also comes to mind: "Am I mad, in a coma, or back in time!" The novella even appeared several times in the series Lost, as a clue to eery happenings to come (even after the finale, many Losties were left wondering what was real).

Horror, at its best, tortures not just its characters, but its audience. If you decide to read this one, be prepared to have the screws turned on you.

Automata 101: Gothic Romance and the Uncanny

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. This blog will outline her experiences teaching an Honors English Composition course about created entities, beginning with the golem of Jewish legend and continuing through cyborgs, robots, androids, and artificial intelligence.

My goal for this section was to introduce the students to the concept of the uncanny and connect it to humanity’s perception of robots. I also wanted to focus on different types of texts in this section. We read short stories, articles, and essays.

We began by reading the classic “uncanny” short story: E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman,” in which a university student, Nathanael, falls in love with an automaton, Olimpia, that he believes is his professor’s daughter. Sigmund Freud used this story in his famous essay on the uncanny to explain the concept. However, we did not read Freud’s essay because it focuses more on castration anxiety than the uncanny. Instead, we read an older essay on the uncanny by Ernst Jentsch, “On the Psychology of the Uncanny (PDF),” published in 1906. This essay posits that our feelings of the uncanny stem from our inability to determine if a figure is alive or not, which is a good, basic concept for us to use in the class.

We began by reading the classic “uncanny” short story: E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman,” in which a university student, Nathanael, falls in love with an automaton, Olimpia, that he believes is his professor’s daughter. Sigmund Freud used this story in his famous essay on the uncanny to explain the concept. However, we did not read Freud’s essay because it focuses more on castration anxiety than the uncanny. Instead, we read an older essay on the uncanny by Ernst Jentsch, “On the Psychology of the Uncanny (PDF),” published in 1906. This essay posits that our feelings of the uncanny stem from our inability to determine if a figure is alive or not, which is a good, basic concept for us to use in the class.

While the reading audience sees this live/not live confusion through the character of Nathanael, another Hoffmann story “The Automata” does a better job in conveying the feeling of the uncanny for everyone. When speaking of the fortune-telling automaton, The Turk, that’s all the rage, one character confesses:

“All figures of this sort,” said Lewis, “which can scarcely be said to counterfeit humanity so much as to travesty it in mere images of living death or inanimate life are most distasteful to me. When I was a little boy, I ran away crying from a waxwork exhibition I was taken to, and even to this day I never can enter a place of the sort without a horrible, eerie, shuddery feeling.

When I see the staring, lifeless, glassy eyes of all the potentates, celebrated heroes, thieves, murderers, and so on, fixed upon me, I feel disposed to cry with Macbeth: ‘Thou hast no speculation in those eyes / Which thou dost glare.’ And I feel certain that most people experience the same feeling, though perhaps not to the same extent. For you may notice that scarcely anyone talks, except in a whisper, in waxwork museums. You hardly ever hear a loud word. But it is not reverence for the Crowned Heads and other great people that produces this universal pianissimo; it is the oppressive sense of being in the presence of something unnatural and gruesome; and what I detest most of all is the mechanical imitation of human motions.”

I wanted to counter these Hoffmann stories with an activity that allowed the students to experience a bit of the uncanny rather than search for it in Hoffmann’s dense, gothic prose. I gave them the assignment to watch several videos of robots and write a response that explained why they found a certain one the most uncanny. I sent them to this Creepiest Robots web page at the Huffington Post. (I had them watch the videos numbered 1, 17, 22, and 23, although plenty of them are uncanny.)

While each one of the four robots had one student choose it as the most uncanny, numbers 1 and 17 were the robots that the students wrote about the most. The class discussion was lively as each student defended his or her choice and asked the other students questions about theirs.

Now that the students had a better grasp of the uncanny, we read “The Uncanny Valley” (1970) by roboticist Masahiro Mori. He argues that robots, androids, and cyborgs that are too human-like in appearance fall into an uncanny valley in human perception. He recommends that the creators of these machines avoid making them resemble people too much. You can see his famous graph that depicts the uncanny valley and an interesting slideshow at this blog.

We followed “The Uncanny Valley” with an article from The New Scientist, “What Puts the Creepy into Robot Crawlies? (PDF)” (2007), by Jim Giles. This article is valuable because it summarizes Mori’s argument and then presents newer research. It explains that researchers, Thierry Chaminade and Ayse Saygin of University College London, use brain scans to observe the parts of subjects’ brains that are activated when they see a human, a humanoid robot, and a mechanical robot performing similar human actions, such as picking up a cup. The researchers believe the feeling of the uncanny can be found in the specific areas of the subjects’ brains that are activated only when the humanoid robot is observed.

We followed “The Uncanny Valley” with an article from The New Scientist, “What Puts the Creepy into Robot Crawlies? (PDF)” (2007), by Jim Giles. This article is valuable because it summarizes Mori’s argument and then presents newer research. It explains that researchers, Thierry Chaminade and Ayse Saygin of University College London, use brain scans to observe the parts of subjects’ brains that are activated when they see a human, a humanoid robot, and a mechanical robot performing similar human actions, such as picking up a cup. The researchers believe the feeling of the uncanny can be found in the specific areas of the subjects’ brains that are activated only when the humanoid robot is observed.

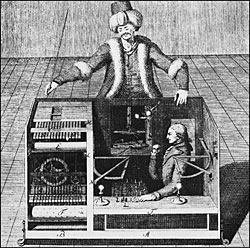

The last texts in this section make an interesting pair: Edgar Allan Poe’s 1836 essay, “Maelzel’s Chess Player” and F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre’s story, “The Clockwork Horror,” that fictionalizes Poe’s essay. In “Maelzel’s Chess Player,” Poe, as a writer for Richmond’s Southern Literary Messenger, investigates a traveling automaton show, featuring the Turk, which played chess in exhibition matches. His essay debunks the Turk and explains how a human is hidden in the elaborate box that houses the false automaton. My purpose in assigning this essay was to expose the students to the idea that robot-like automata were not uncommon exhibitions at the time that Hoffmann and his contemporaries were writing about them in fiction.

In fact, the automaton that Poe saw in 1836 was probably Hoffmann’s inspiration for his Turkish fortune-teller. The same machine had been touring Europe and America since the late 1700s. Jane Irwin has created a fabulous web comic about the history of the Turk, Clockwork Game: The Illustrious Career of a Chess-Playing Automaton. I’ve just started reading it. Too bad I didn’t know about the comic when I was teaching this section. I’ve put it on the course website.

Poe’s essay tells his readers that he commandeers the audience after the Turk’s game and explains how the box contains a hidden chess player and uses magician’s tricks to hide the player during Maezel’s lengthy exposure of the cabinet. Here we glimpse the writer who will create C. Auguste Dupin and his stories of ratiocination. Since Poe’s prose is dense and a bit hard to get through, I also assigned MacIntyre’s story to give the students an account of Poe’s reasoning in a more accessible form. MacIntyre did some research for this horror story and was able to fill in some blanks that Poe left out.

Poe’s essay tells his readers that he commandeers the audience after the Turk’s game and explains how the box contains a hidden chess player and uses magician’s tricks to hide the player during Maezel’s lengthy exposure of the cabinet. Here we glimpse the writer who will create C. Auguste Dupin and his stories of ratiocination. Since Poe’s prose is dense and a bit hard to get through, I also assigned MacIntyre’s story to give the students an account of Poe’s reasoning in a more accessible form. MacIntyre did some research for this horror story and was able to fill in some blanks that Poe left out.

I’m happy with the way this section turned out. The students read several different types of texts–from difficult nineteenth-century authors to an article from a popular science magazine–examined the uncanny from different perspectives, and gained some historical context. They’ll get more history in the next section when we begin with early-twentieth-century robots in R. U. R. and Metropolis.

Full Details

Full Details