Forays into Fantasy: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife and the Beginnings of Urban Fantasy

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF examines some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Fritz Leiber (1910–1992) is indisputably one of the most important science fiction and fantasy writers of the twentieth century, recipient of the Science Fiction Writers of America’s Grand Master Award and the World Fantasy Award for Lifetime Achievement, as well as six Hugos and four Nebulas. His science fiction is some of the best of its era, including Gather, Darkness (1943), Hugo winner The Big Time (1958), and a series of great short stories for Galaxy during the 1950s. Despite his achievements in SF, he is better known today for his fantasy, due primarily to his sword and sorcery sequence featuring Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, which began with “Two Sought Adventure” (aka “The Jewels in the Forest”) in 1939, and continued throughout his long career (and which should be the subject for a future post in this series).

Fritz Leiber (1910–1992) is indisputably one of the most important science fiction and fantasy writers of the twentieth century, recipient of the Science Fiction Writers of America’s Grand Master Award and the World Fantasy Award for Lifetime Achievement, as well as six Hugos and four Nebulas. His science fiction is some of the best of its era, including Gather, Darkness (1943), Hugo winner The Big Time (1958), and a series of great short stories for Galaxy during the 1950s. Despite his achievements in SF, he is better known today for his fantasy, due primarily to his sword and sorcery sequence featuring Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, which began with “Two Sought Adventure” (aka “The Jewels in the Forest”) in 1939, and continued throughout his long career (and which should be the subject for a future post in this series).

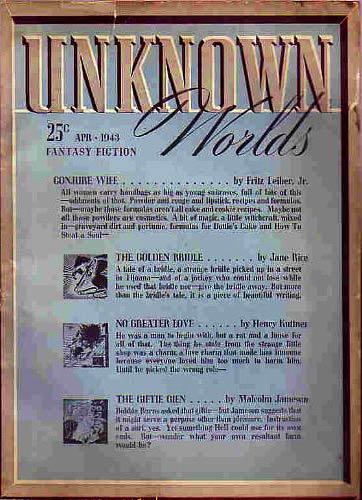

Leiber may also have been more comfortable writing fantasy, turning to science fiction at least in part due to the lack of fantasy publishing outlets following the demise of John W. Campbell’s Unknown magazine in 1943, after which science fiction would dominate the genre magazine (and eventually the book publishing) landscape until the 1970s. Due to Unknown’s market for sophisticated fantasy, the years 1939 to 1943 produced a disproportionate amount of great fantasy, much of which is still read today. Last year I wrote about three of these—Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp’s Enchanter stories, Jack Williamson’s Darker Than You Think, and A. E. Van Vogt’s The Book of Ptath—and as I return to this period in the history of fantasy, several additional Unknown stories will be looked at. Along with the first five Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories, Fritz Leiber’s contributions to Unknown include the classic “Smoke Ghost” (1941) and the novel Conjure Wife (1943), which was first published in book form, slightly revised and updated, in 1952 as part of the omnibus Witches Three.

The book revision, still available today, is essentially the same as the 1943 Unknown (by then known as Unknown Worlds) version. It’s the story of Norman Saylor, professor of sociology at conservative Hempnell College, and his wife Tansy, whose job in 1940s academia is to fulfill the duties of a “faculty wife”, supporting Norman by helping fulfill the social obligations that appear to be at least as important to success there as scholarly accomplishments.

The book revision, still available today, is essentially the same as the 1943 Unknown (by then known as Unknown Worlds) version. It’s the story of Norman Saylor, professor of sociology at conservative Hempnell College, and his wife Tansy, whose job in 1940s academia is to fulfill the duties of a “faculty wife”, supporting Norman by helping fulfill the social obligations that appear to be at least as important to success there as scholarly accomplishments.

“It seemed to Norman that there was something incredible about his success at Hempnell, something magical and frightening, as if he and Tansy were a young warrior and squaw who had blundered into a realm of ancestral ghosts and had managed to convince those grim phantoms that they too were properly buried tribal elders, fit to share the supernatural rulership; always managing to keep secret their true flesh-and-blood nature despite a thousand threatened disclosures, because Tansy happened to know the right protective charms.”

When Norman accidentally discovers that Tansy really is using witchcraft to protect him and advance his career, his rational world-view won’t let him accept that his musings are based on actual foundations. He accuses his wife of succumbing to juvenile superstitions (fittingly, Norman is a scholar of the sociology of superstitious beliefs, and has no doubts about their psycho-social origins), and she agrees to give up the practice, against her better judgment. Immediately, Norman’s world is upended—students accuse him of sexual advances and unfair grading; administrators begin to question his controversial classroom statements and the propriety of his private life. He loses the department chairmanship he had thought he was next in line for. And the stone dragon which had been a fixture on the building next to his office seems to be creeping closer each time he looks in its direction…

Eventually, Norman can no longer deny the evidence, and must accept Tansy’s story. Her charms really had been protecting him—protections that were sorely needed, given that the other Hempnell faculty wives were ready to use their own conjuring to help their own husbands and bring down the Saylors.

Eventually, Norman can no longer deny the evidence, and must accept Tansy’s story. Her charms really had been protecting him—protections that were sorely needed, given that the other Hempnell faculty wives were ready to use their own conjuring to help their own husbands and bring down the Saylors.

“…Witch women using magic as Tansy had, to advance their husbands’ careers and their own. Making use of their husbands’ special knowledge to give magic a modern twist… Why not carry it a step further? Maybe all women were the same. Guardians of mankind’s ancient customs and traditions, including the practice of witchcraft. Fighting their husbands’ battles from behind the scenes, by sorcery. Keeping it a secret; and on those occasions when they were discovered, conveniently explaining it as feminine susceptibility to superstitious fads. Half of the human race still actively practicing sorcery. Why not?”

But by the time Norman can accept this, it may be too late. Three of the Hempnell witches are working together against him and Tansy, whose soul is stolen, preventing her from helping Norman, and endangering her life. By this point, the novel has moved from an amusing story of college politics to a supernatural fantasy, and finally into an effective horror/suspense story. The Saylor’s enemies are shown to be capable of going to any means to keep Norman from regaining his position. In order to save Tansy, he must fight them by combining his own systematic intellectual approach and the application of magic. “To tackle it in dead seriousness, to open your mind deliberately to superstition—that was to join hands with the forces pushing the world back into the dark ages, to cancel the term ‘science’ out of the equation…. He could not believe it. He did not believe it. Yet somehow he had to believe it.”

The story is problematic from a gender perspective, but not unambiguously so. The men in the novel, especially Norman, are presented as rational, while the women are witches, tapping into the supernatural, which could be read as the literalization of a misogynistic stereotype. But from the perspective of the early ‘40s, when the story first appeared, could Leiber have been pointing out that, since women did not have access to men’s positions in society, they would still find a way to exercise power, even if it does have to be from the shadows? All the professors at Hempnell are men, but the women are presented as having just as much, and possibly more, influence over the college’s power structure. I’m not sure what to make of this aspect of the story, but someone better versed than I at evaluating literature from a feminist perspective ought to find Leiber’s novel an interesting challenge.

The story is problematic from a gender perspective, but not unambiguously so. The men in the novel, especially Norman, are presented as rational, while the women are witches, tapping into the supernatural, which could be read as the literalization of a misogynistic stereotype. But from the perspective of the early ‘40s, when the story first appeared, could Leiber have been pointing out that, since women did not have access to men’s positions in society, they would still find a way to exercise power, even if it does have to be from the shadows? All the professors at Hempnell are men, but the women are presented as having just as much, and possibly more, influence over the college’s power structure. I’m not sure what to make of this aspect of the story, but someone better versed than I at evaluating literature from a feminist perspective ought to find Leiber’s novel an interesting challenge.

In looking at the history of fantasy, Conjure Wife presents the opportunity to introduce urban fantasy into the picture. The term “urban fantasy” began to appear regularly during the 1980s to distinguish fantasies set in contemporary urban setting from the more popular secondary world rural-based fantasies such as The Lord of the Rings. In these stories, the fantasy elements intrude into the world we know. Though this type of story had a long history (Dracula, for example, could fit the definition), Fritz Leiber’s work was seen as its modern progenitor. According to Brian Stableford, in his Historical Dictionary of Fantasy Literature (2005):

“The development of urban fantasy was pioneered by Fritz Leiber in such stories as “Smoke Ghost” and “The Girl with the Hungry Eyes,” but the subgenre was given more definitive form in the work of Charles de Lint and such individual items as Mark Helprin’s Winter’s Tale, Megan Lindholm’s The Wizard of the Pigeons, Emma Bull’s War for the Oaks, Michael Moorcock’s Mother London, Kara Dalkey’s Steel Rose, Richard Bowes’s Minions of the Moon (1999), Tanya Huff’s Gate of Darkness, Gate of Light, Neal Shusterman’s Downsiders (1999), and Paul Brandon’s The Wild Reel (2004).”

Conjure Wife would earlier have been termed a “contemporary fantasy”, but took on the “urban fantasy” mantle once that category was coined. To further confuse the definitional picture, “urban fantasy” has recently been co-opted as the name of a popular publishing and marketing category, coming to denote “an alternate version of our modern world where humans (often with special talents) and supernatural beings—most typically vampires, werewolves, assorted other shapeshifters, and very humanlike elves or fairies—interact via adventure, melodrama, intrigue, and sex. A closely related, indeed overlapping, publishing classification is paranormal romance.” (David Langford, Encyclopedia of Fantasy, 2012).

Conjure Wife would earlier have been termed a “contemporary fantasy”, but took on the “urban fantasy” mantle once that category was coined. To further confuse the definitional picture, “urban fantasy” has recently been co-opted as the name of a popular publishing and marketing category, coming to denote “an alternate version of our modern world where humans (often with special talents) and supernatural beings—most typically vampires, werewolves, assorted other shapeshifters, and very humanlike elves or fairies—interact via adventure, melodrama, intrigue, and sex. A closely related, indeed overlapping, publishing classification is paranormal romance.” (David Langford, Encyclopedia of Fantasy, 2012).

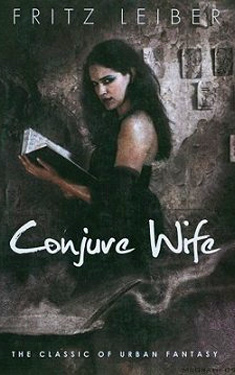

The current popularity of this new type of urban fantasy explains why the most recent edition of Conjure Wife, published by Orb in 2009, refers to it on the front cover as “The Classic of Urban Fantasy” and uses a cover painting of a vaguely gothic-looking young woman dressed in black, reminiscent of so many other urban fantasy/paranormal romance covers, which usually seem to be variations on the sexy black-clad weapon-wielding heroine. (Since the only weaponry in Conjure Wife is witchcraft, the woman on the cover wields a book of spells!)

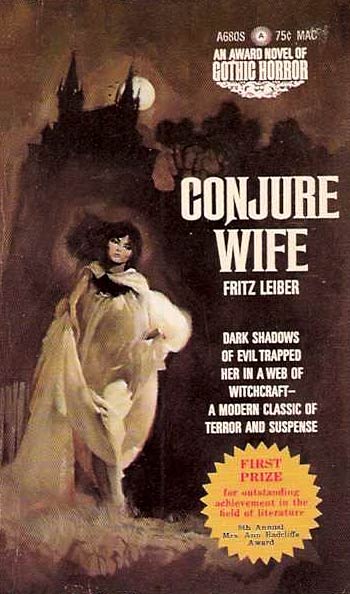

Earlier editions of the book market it as more of a contemporary horror/gothic novel, more consistent with the publishing categories of the times. (It was also re-released in the early ‘60s under the title Burn, Witch, Burn, after the title of a 1962 British film based on the novel. The film has its admirers, but I haven’t been able to see it yet…) A 1977 Ace edition seems to be going after the Exorcist/Rosemary’s Baby audience, with the tagline “No power on Earth could save her from the ultimate violation…” In 1953, a Lion Books edition refers to it as a science-fantasy novel, and tries to draw in readers with the tagline “Potions in the house… Evil in the air… And a witch in his bed”!

Conjure Wife has remained popular enough, then, to spawn a film, and remain in print almost continuously since its first book release sixty years ago. The ability of (or at least the attempts by) publishers to market it to a variety of audiences is indicative of the genre blending that it accomplishes. And don’t forget that some of the subgenres it has been marketed under didn’t even exist when the novel was written, indicating Leiber’s role as a progenitor of a variety of modern genre trends. I’m not sure whether today’s urban fantasy fans will find what they are looking for in this “classic of urban fantasy”—the supernatural and horror elements will probably seem quite understated to those used to vampire hunters and seductive werewolves—but for anyone interested in the development of modern fantasy, or anyone looking for an economically told and elegantly written (Leiber’s prose was well above the genre standard of his time) combination of social satire, suspense, horror, and the supernatural, Conjure Wife will be a great read.

Conjure Wife has remained popular enough, then, to spawn a film, and remain in print almost continuously since its first book release sixty years ago. The ability of (or at least the attempts by) publishers to market it to a variety of audiences is indicative of the genre blending that it accomplishes. And don’t forget that some of the subgenres it has been marketed under didn’t even exist when the novel was written, indicating Leiber’s role as a progenitor of a variety of modern genre trends. I’m not sure whether today’s urban fantasy fans will find what they are looking for in this “classic of urban fantasy”—the supernatural and horror elements will probably seem quite understated to those used to vampire hunters and seductive werewolves—but for anyone interested in the development of modern fantasy, or anyone looking for an economically told and elegantly written (Leiber’s prose was well above the genre standard of his time) combination of social satire, suspense, horror, and the supernatural, Conjure Wife will be a great read.

Full Details

Full Details

2 Comments

Well, seeing there is this overwhelming flood of vampire/werewolf related romances and purported horror narratives, often featuring that irritating love-triangular so familiar in most recent YA fantasy, going back to “the roots” will be a welcome reprieve … relief. I have this book on my reading list for quite some time now and guess it’s high-time I give it the attention it appears to deserve.

Hi, Emil. This is a unique situation where what was once a simple (and not very specific, really) descriptive term used to distinguish this type of fantasy from the better-known “secondary world” genre (Tolkien, etc.) got co-opted as a category used by publishers do identify a popular subgenre. Whatever anyone thinks of the current urban fantasy boom (and I suspect “Sturgeon’s Law” applies), or how antecedents like Conjure Wife relate to it, Leiber’s work will endure on its own unique merits.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.