GMRC Review: The Ship Who Sang

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. It’s no surprise to us that Rhonda’s is the first featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. It’s no surprise to us that Rhonda’s is the first featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Anne McCaffrey’s The Ship Who Sang is a collection of six novelettes and novellas published between 1961 and 1969. Most of them stand alone but also work well as the continuous story of Helva, the ship who sang. McCaffrey creates a world in which humans have colonized other planets and have discovered many types of life forms “out there.” In this world, however, humans are still born with birth defects. These babies are tested for high levels of brain functions. If they do not pass the tests, they are euthanasized. If they do pass the test, their parents are given the choice between euthanasia or placing them in a school to learn to be the “brains” of a spaceship. These spaceships work for Cencom, delivering important cargo, transporting dignitaries, and other humanitarian or emergency jobs.

Anne McCaffrey’s The Ship Who Sang is a collection of six novelettes and novellas published between 1961 and 1969. Most of them stand alone but also work well as the continuous story of Helva, the ship who sang. McCaffrey creates a world in which humans have colonized other planets and have discovered many types of life forms “out there.” In this world, however, humans are still born with birth defects. These babies are tested for high levels of brain functions. If they do not pass the tests, they are euthanasized. If they do pass the test, their parents are given the choice between euthanasia or placing them in a school to learn to be the “brains” of a spaceship. These spaceships work for Cencom, delivering important cargo, transporting dignitaries, and other humanitarian or emergency jobs.

These babies are taken from their parents and entered into a school, where they are placed into smaller machine bodies and trained for their ultimate insertion into a ship. The children are given drugs to stunt their growth so that they may be permanently fitted into the control column of the ship. For Helva, the ship’s mobility is her mobility; its sensors are her senses. Her body is pumped nutrients, and she never sleeps. McCaffrey’s cyborg ship idea is fascinating, and she explores its potential in the first chapter. Readers learn more about Helva’s existence in the successive chapters.

The class of ship that Helva becomes is called a BB ship, signaling the two components, the brains, Helva and her ilk, and the brawns, the fully mobile human pilots who travel with the ships. The chapters explore Helva’s relationships with her brawns as she and they undertake the assignments given to them by Cencom. In my opinion, the first three chapters are the strongest narratives, both in their relation to one another and as independent stories.

Reading this collection more than forty years after the individual parts were written, I can see how McCaffrey is working with early feminist ideas. Helva is strong, opinionated, and smarter than all of the men she encounters. She is able to choose her brawns, who must court her (McCaffrey’s term). She becomes financially independent in the course of the book, fights for her rights, makes choices that will ensure her growth and well-being. However, the weakness is that McCaffrey can’t quite break out of the idea that the brain-brawn relationship is a traditional concept of marriage. We see Helva fall in love with, break up with and enter into an “oil and water” relationship with various brawns. McCaffrey does not exactly force compulsory heterosexuality on Helva because she once has a female brawn (whom she often misses when the men seem incompatible to her).

Reading this collection more than forty years after the individual parts were written, I can see how McCaffrey is working with early feminist ideas. Helva is strong, opinionated, and smarter than all of the men she encounters. She is able to choose her brawns, who must court her (McCaffrey’s term). She becomes financially independent in the course of the book, fights for her rights, makes choices that will ensure her growth and well-being. However, the weakness is that McCaffrey can’t quite break out of the idea that the brain-brawn relationship is a traditional concept of marriage. We see Helva fall in love with, break up with and enter into an “oil and water” relationship with various brawns. McCaffrey does not exactly force compulsory heterosexuality on Helva because she once has a female brawn (whom she often misses when the men seem incompatible to her).

I applaud McCaffrey for what she was trying to do, but from my future perspective The Ship Who Sang is dated in the way it handles (and focuses on) relationships. I would like to see Helva using her brains to solve problems related to her assignments rather than worrying about her relationships with past, present, and future brawns. However, Helva is a fantastic feminist character and offers strong evidence against the critics who say that science fiction authors can’t create characters with depth.

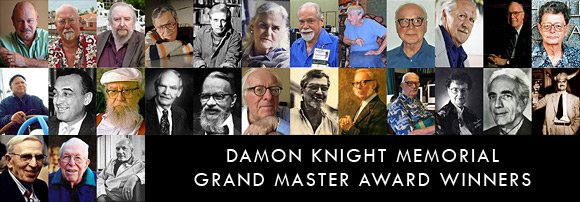

2012 WWEnd Grand Master Reading Challenge

Well, we’re a little bit late to the party but we have finally launched our reading challenge! As you may have guessed from the title and the badge our reading challenge is focused on the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award winning authors. If you’re not familiar with the Grand Master Award it’s an award for lifetime achievement in SF/F given out by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. The award is given semi-annually to a living author usually during the Nebula Award ceremony though it’s not a Nebula itself.

Well, we’re a little bit late to the party but we have finally launched our reading challenge! As you may have guessed from the title and the badge our reading challenge is focused on the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award winning authors. If you’re not familiar with the Grand Master Award it’s an award for lifetime achievement in SF/F given out by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. The award is given semi-annually to a living author usually during the Nebula Award ceremony though it’s not a Nebula itself.

Heinlein, Bester, McCaffrey, Asimov, Clarke and of course Damon Knight himself… these authors are some of the giants of genre fiction and after adding the list to the site we hit on the idea of building a challenge around them. But not just a challenge. Here at WWEnd we have to do things just a bit differently so we decided to incorporate BookTrackr™ into it so you can track your progress throughout the year.

Why? Well, your typical reading challenge usually starts out with a lot of enthusiasm but over time it’s easy to get lazy and lose interest. Reading for a challenge is a solitary endeavor that goes something like this: you pick a book for your challenge, bugger off to read it, two weeks later when you’re done you blog about it and hope somebody reads your blog. Then you do it again and again – pretty much in a vaccuum. Sure you can hit the blogs to see how other people are doing but that takes a lot of time and gets pretty spread out as the months go on.

BookTrackr makes it easy to get involved and stay involved. If you look at the Grand Master Reading Challenge page you’ll see our solution in action. Every particpant in the challenge goes into a single table where you can directly compare your progress with everyone else. From that page you’ll be able to see which authors and books are being read and access all the reviews for the challenge. It’s meant to foster a bit of friendly competition between members; where we can all help to keep each other motivated. Plus, it’s just fun to fill out all the slots!

How the GMRC works:

The goal of the WWEnd Grand Master Reading Challenge is to read 12 books — 1 each by 12 Grand Master authors — in 12 months and write at least 6 reviews. That’s it. Not a huge challenge compared to some others you’ve probably seen but it’s a good steady challenge for those of us with limited time. It’s also one that won’t scare off the slow readers amongst us. Raise your hand if you’re one of us.

Now I know some of you Evelyn Wood grads are thinking "I can read 12 books in a couple months…" That’s awesome, but that’s not what this challenge is about. You’re supposed to pace yourself and read a book each month then share your thoughts with the rest of us. Think of it as a "relax-a-challenge" if you will. Read a book. Post your review here on WWEnd, or post an extract here and link back to your blog for the full review. Then do it again. Read. Review. Repeat.

Further incentive:

We get a lot of great reviews here on WWEnd every week and we expect that we’ll get a bunch more through this challenge so we want to reward you for the effort with some prizes and some love. Each week we’re going to cherry pick the best reviews to feature in the WWEnd blog as a guest post. We’ll include an intro for you and promote your blog to our members. Try and drive a little traffic your way. You’ll also receive a GMRC button for the effort. Wear it proudly to your next convention.

At the end of each month WWEnd members will vote on the featured reviews and the winner will earn everlasting glory and some swag from the WWEnd prize box. Prizes include: T-Shirts, buttons, books and bookmarks etc. Remember how I said we want you to pace yourself? If you do, you’ll have 12 chances to win. And, of course, everyone who completes the challenge will receive a prize at the end. Schweet.

Anyway, I’ve gone on too long. Kudos if you read down this far! There’s more information and instructions on the GMRC page and on the Grand Master Award page and you can hit us with questions in the comments or in the forums.

So, who’s in? What do you think of our little scheme of marching up and down the square?

2011 Philip K. Dick Award Shortlist

The shortlist for the 2011 Philip K. Dick Award has been announced. The nominees are:

- The Company Man – Robert Jackson Bennett (Orbit)

- Deadline – Mira Grant (Orbit)

- The Other – Matthew Hughes (Underland Press)

- A Soldier’s Duty – Jean Johnson (Ace)

- The Postmortal – Drew Magary (Penguin)

- After the Apocalypse – Maureen F. McHugh (Small Beer Press)

- Samuil Petrovitch Trilogy – Simon Morden (Orbit)

The winner will be announced April 6, 2012 at Norwescon 35 in SeaTac WA. Congratulations to all the nominees.

What do you think of this list? Any favorites to win?

Titas Groan: Favorite Fantasy

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. Check out his review of one of the all-time fantasy classics.

In Titus Groan, Mervyn Peake created a masterwork of alternate reality, unlike anything else in literature. For good reason, David Pringle begins the date range for his Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels in 1946, so that this can be the first entry on his list. It achieves its unique vision with a combination of vivid setting and characterization, both built up with a luxurious edifice of language that is a joy to read.

In Titus Groan, Mervyn Peake created a masterwork of alternate reality, unlike anything else in literature. For good reason, David Pringle begins the date range for his Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels in 1946, so that this can be the first entry on his list. It achieves its unique vision with a combination of vivid setting and characterization, both built up with a luxurious edifice of language that is a joy to read.

Titus Groan is the first novel of Peake’s Gormenghast Series, of which three novels were published during his lifetime, with other planned volumes never completed. His widow’s completion of the fourth novel, Titus Awakes, was published in 2011.

It’s a difficult novel to characterize in terms of genre definition. Though generally categorized as fantasy, it doesn’t fit neatly into the category. It takes place in a fantasy setting, in the sense that it is a place and/or time that is nonexistent, yet nothing literally “fantastic” happens in the novel. There are no explicit magical or supernatural elements in the story. The building up of the sense of place is one of the great enjoyments of the novel, so any summation will fail to do it justice, but the words that come to mind in describing Gormenghast, the castle setting, are “weight” and “tradition.” The characters have Dickensian names like Sepulchrave, Prunesquallor, and Swelter, and there are other echoes of British culture, which the setting may in part be a commentary on.

Titus, born at the beginning of the story, is destined to be the 77th Earl of Gormenghast, implying (though it is not made explicit) a 2,000-year dynasty. Throughout this time (at least), the castle and the surrounding lands have observed strict and unchanging rituals, the specifics of which are nonsensical (and are humorous in their description), but which all the characters agree on the importance of. Though such literal speculation is probably pointless, it’s even possible that the setting could be in the far future, after humanity has lost most of its technology and returned to a sort of feudal existence even more rigid than that of the Middle Ages. (It would not surprise me if Peake was an influence on Jack Vance’s Dying Earth.)

The world of Gormenghast has the “Dark Ages” feel beloved of fantasy writers, but there are oddities, such as Dr. Prunesquallor’s knowledge of anatomy and chemistry, and the fact that characters drink coffee, that seem anachronistic. Despite the lack of change, there is also a sense of decline. The reasons for the rituals are forgotten; sections of the castle have not been visited for centuries; the hereditary leaders are subject to imbecility and mental illness; only Steerpike, the outsider whose story provides the primary plot of the novel, notices details of his surroundings that the other characters give no thought to.

In this world, change is considered to be the greatest evil. Just as Titus is born to continue carrying on the traditions, Steerpike is introduced as an agent of change. There are several ways to interpret the role of Steerpike in the story. He is born as a kitchen laborer, destined to drudgery in the lowest level of the castle, but is determined to find a way out, slowly insinuating himself into the lives of the high-born characters by finding ways of making himself indispensable to them. Is he a working-class revolutionary looking to bring equality to this society (a view he espouses at times), or rather a sort of infection rising up from the depths of the castle to destroy the lives of the other characters (a reading consistent with his actions)? At times, we sympathize with Steerpike, and admire his intelligence and willingness to act, in strong contrast to the ritual-bound and seemingly lifeless existence of the other characters.

In this world, change is considered to be the greatest evil. Just as Titus is born to continue carrying on the traditions, Steerpike is introduced as an agent of change. There are several ways to interpret the role of Steerpike in the story. He is born as a kitchen laborer, destined to drudgery in the lowest level of the castle, but is determined to find a way out, slowly insinuating himself into the lives of the high-born characters by finding ways of making himself indispensable to them. Is he a working-class revolutionary looking to bring equality to this society (a view he espouses at times), or rather a sort of infection rising up from the depths of the castle to destroy the lives of the other characters (a reading consistent with his actions)? At times, we sympathize with Steerpike, and admire his intelligence and willingness to act, in strong contrast to the ritual-bound and seemingly lifeless existence of the other characters.

On the other hand, we also sympathize with the Earl’s family. They are not evil, and are just as much bound by tradition as the servants, being forced to participate in endless boring rituals, without any other purpose in life. As a result, Lord Sepulchrave (the 76th Earl) retreats into his library and is continually depressed, his wife Gertrude retreats from the society of other people and responds emotionally only to pets, and their teenage daughter Fuchsia wanders mentally and physically in search of some sort of happiness or enervation that seems out of reach. We might approve of a “shaking up” of this world, but Steerpike revels not just in change but in destruction, setting in motion a series of events that eventually erupt into violence, and his motives seem entirely selfish.

It is tempting to see an allegory. Is Gormenghast meant to represent the post-War British society in which Peake lived, its class system resisting the modernity brought on by the rapid historical changes resulting from world war and the decline of Britain’s empire? If so, it could be that Peake was both criticizing this world and regretting its destruction. This ambiguity of reaction to historical change is not atypical, as evidenced by the impulses toward both conservatism and liberalism characteristic of modern societies. An unchanging society is stifling to individuals, but change is painful to those accustomed to (especially if they are invested in) the status quo.

Part of the genius of Titus Groan, however, is that readers with no comprehension of (or interest in) the potential subtext, if they are lovers of good writing, fictional world-building, and vivid characterization, will still see the novel as a classic of fantasy. Peake immerses us in a world that is both alien and familiar. Each sentence adds a brick to the edifice of both Gormenghast and the novel that describes it. The word “classic” may be overused, but I’m using it here!

Outside the Norm: Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin and Oryx and Crake

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

Margaret Atwood has famously denied that she writes “science fiction,” claiming instead that she writes “speculative fiction,” a claim that always sounds less condescending coming from Harlan Ellison than it does from Atwood. This is probably because Ellison knows what he’s trying to define, and Atwood is trying to craft a definition that excludes her own writing from science fiction. According to Atwood, science fiction “is when you have chemicals and rockets” or “monsters and spaceships” or “talking squids in outer space.” For analyses of Atwood’s definitions, see Peter Watts, “Margaret Atwood and the Hierarchy of Contempt” and David Langford, “Bits and Pieces.”

Margaret Atwood has famously denied that she writes “science fiction,” claiming instead that she writes “speculative fiction,” a claim that always sounds less condescending coming from Harlan Ellison than it does from Atwood. This is probably because Ellison knows what he’s trying to define, and Atwood is trying to craft a definition that excludes her own writing from science fiction. According to Atwood, science fiction “is when you have chemicals and rockets” or “monsters and spaceships” or “talking squids in outer space.” For analyses of Atwood’s definitions, see Peter Watts, “Margaret Atwood and the Hierarchy of Contempt” and David Langford, “Bits and Pieces.”

My recent reading of two Atwood novels shows me that she can write science fiction badly and that she can write science fiction well. To be fair, I believe that she was trying to write bad science fiction in The Blind Assassin (2000). This winner of the Booker Prize is a multi-layered novel in which octogenarian Iris Chase Griffen recounts the life of her sister Laura Chase, the author of The Blind Assassin. This fictional book-within-a-book was published after Laura’s untimely death and gained a cult following. The sections of Atwood’s book alternate between Iris writing the story of the Chase girls’ youth and Laura’s novel. The plot of this internal novel is simple: in the 1930s and 40s a married upper-class woman has a clandestine affair with a lower-class man who is on the run. Both these characters are unnamed. He is most likely an active communist who is being pursued by the authorities. He makes his living by writing for science fiction pulp magazines. Most of these chapters follow the formula of the woman visiting the man at his current hideout where their post-coital pillow talk consists of the man entertaining her with science fiction stories he makes up on the spot. Their first foray into storytelling begins like this:

What will it be, then? he says. Dinner jackets and romance, or shipwrecks on a barren coast? You have your pick: jungles, tropical islands, mountains. Or another dimension of space—that’s what I’m best at.

Another dimension of space? Oh really!

Don’t scoff, it’s a useful address. Anything you like can happen there. Spaceships and skin-tight uniforms, ray guns, Martians with the bodies of giant squids, that sort of thing. (9)

It is significant that the character’s list mirrors the entities that Atwood herself references in interviews as I have shown above. Clearly, Atwood, as the writer of The Blind Assassin, and the male writer have a very low opinion of science fiction and its abilities to develop character or plot. For him, science fiction is about an Other (completely undeveloped) and cheap thrills, as their negotiations show:

Then you could have a pack of nude women who’ve been dead for three thousand years, with lithe, curvaceous figures, ruby-red lips, azure hair in a foam of tumbled curls, and eyes like snake-filled pits. But I don’t think I could fob those off on you. Lurid isn’t your style.

You never know I might like them.

I doubt it. They’re for the huddled masses. Popular on the covers though—they’ll writhe all over a fellow, they have to be beaten off with rifle butts.

Could I have another dimension of space, and also the tombs and the dead women, please?

That’s a tall order, but I’ll see with I can do. I could throw in some sacrificial virgins as well, with metal breastplates, and silver ankle chains and diaphanous vestments. And a pack of ravening wolves, extra. (9)

This negotiation ends with him beginning his story of the planet Zycron, which contains some of the ideas he discusses above. The story has too many plot details, many of them never expanded nor explored. While not all of his story ideas are completely cliché in execution, these two pieces of dialog demonstrate how Atwood pigeonholes science fiction.

Unfortunately for Atwood, the story of the lovers and their pulp pursuits are much more interesting than Iris’ main narrative which grows tedious after a while. Also, I figured out the ending surprises with more than 200 pages left which did not increase my interest in the stories Iris tells in either the past or the present. Also, I had trouble reconciling the characters of Iris in the past with Iris in the present.

Oryx and Crake (2003) shows that Atwood can write good science fiction; however, she would call it speculative fiction, or writing “based on rigorously-researched science, extrapolating real technological and social trends into the future” (Watts 2). And I thought that was what science fiction was. Atwood creates an interesting post-apocalyptic world in which there is one human survivor who calls himself Snowman. Snowman is the caretaker of a race of bio-engineered humanoids, who were created by his friend Crake. According to Crake, all aggression, greed, and competition have been eliminated in this race. They have an advanced life cycle, becoming “adults” after only a few years. They live a pre-lapsarian lifestyle and eat roots, fruits, and grass. Snowman serves as kind of prophet for them. He teaches them about the flotsam they discover from the previous civilization, telling them if it is useful or dangerous.

Oryx and Crake (2003) shows that Atwood can write good science fiction; however, she would call it speculative fiction, or writing “based on rigorously-researched science, extrapolating real technological and social trends into the future” (Watts 2). And I thought that was what science fiction was. Atwood creates an interesting post-apocalyptic world in which there is one human survivor who calls himself Snowman. Snowman is the caretaker of a race of bio-engineered humanoids, who were created by his friend Crake. According to Crake, all aggression, greed, and competition have been eliminated in this race. They have an advanced life cycle, becoming “adults” after only a few years. They live a pre-lapsarian lifestyle and eat roots, fruits, and grass. Snowman serves as kind of prophet for them. He teaches them about the flotsam they discover from the previous civilization, telling them if it is useful or dangerous.

Before he became the prophet of the Crakers (as he calls them), Snowman was Jimmy, who grew up in an enclosed corporate compound called OrganInc Farms. His father was a prominent bio-engineer working on the Pigoon Project, which created pigs that would grow “an assortment of foolproof human-tissue organs” for transplanting into humans (22). These compounds were mostly self-contained with malls, schools, hospitals, etc. that served the needs of the employees and their families. The compounds are connected by tube trains. The areas in between are called pleebland (read pleeb-land), where the mass of humanity lives: economically disadvantaged, diseased, and the ultimate consumers for the products and techniques created in the compounds. This sociological layout reminds me very much of the world Marge Piercy creates in He, She and It, except that Piercy’s economy is based on computer technology and virtual reality instead of bio-engineering.

Snowman’s narrative covers just a few days in his present as he tries to survive in this devastated landscape where food is scarce and new predators, which were former science projects housed in labs, roam. There are snats (a cross between snakes and rats) and wolvogs (a cross between a dog and a wolf). Also, the pigoons have become carnivores and are getting smarter. The bulk of the past story is about Jimmy, how he came to be a survivor, his love for Oryx, and his friend Crake’s ambition to create better human beings. The end of the book finally shows the readers how the rest of humanity met its demise and the roles that Jimmy, Oryx and Crake played in that disaster.

This book was very enjoyable. The science seems science-y enough, and her portrayal of “reality” broadcasts over the internet, where one could find the Noodie News, open heart surgeries, live coverage of executions, and, of course, enough pornography to cover any viewer’s choices or fetishes, seems especially prescient. The plot is well-paced, and both the present and past events are interesting, so I never found myself wishing I could move on to the next time period, like I did with The Blind Assassin. While I cannot say that I liked The Blind Assassin as much as I liked Oryx and Crake, Atwood writes beautifully and is a pleasure to read. I plan to read The Year of the Flood and The Handmaid’s Talec later this year for this blog.

Full Details

Full Details