GMRC Review: The Golden Apples of the Sun and Other Stories

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s third featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

Editor’s Note: Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her excellent blog series Automata 101 and her new series Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s third featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge.

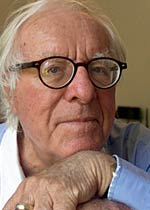

Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun and Other Stories (1990) contains short stories from two of his previous works: one by the same name, published in 1953, and R is for Rocket, published in 1962. This reprint contains all of the stories from R is for Rocket and eighteen of the original twenty-two stories in the previous edition of Golden Apples. (The two collections had a couple of stories in both.)

Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun and Other Stories (1990) contains short stories from two of his previous works: one by the same name, published in 1953, and R is for Rocket, published in 1962. This reprint contains all of the stories from R is for Rocket and eighteen of the original twenty-two stories in the previous edition of Golden Apples. (The two collections had a couple of stories in both.)

The stories from the original Golden Apples demonstrate the range of Bradbury’s writing. Many of them were originally published in mainstream publications, such as The New Yorker, Esquire, The Saturday Evening Post, and Colliers, and don’t demonstrate any science fiction or fantasy elements. They do, however, convey a sense of wonder and otherness. Because of this, many of them were recycled for HBO’s 1980s series, Ray Bradbury Theater. The strongest of these stories seem very current. “I See You Never” recounts the deportation of a Mexican immigrant who had overstayed his visa. “Sun and Shadow” is set in Mexico and explores a poor homeowner’s objection to his house being used as “local color” in the photos of an American fashion photographer. The protagonist in “The Murderer” reacts to modern technology in the same way that many of us wish we could. The murderer in “The Fruit in the Bottom of the Bowl” worries about leaving evidence behind.

The weaker stories do seem very dated. Many of them have ambiguous time settings, placed in either our past or an isolated “land that time forgot” setting. For this reason, I did not like “The Great Wide World Over There” and “Powerhouse.” I found “The Big Black and White Game” particularly puzzling. In telling about a baseball game between the white and black employees of a resort hotel, Bradbury displays that type of 1940s racism that doesn’t think it is racist. He clearly wants to denounce the overt racism of the white women in the story, but then he has the following passage, which I think is supposed to be complimentary:

"How easily the dark people had come running first, like those slow-motion deer and antelopes in those African moving pictures, like things in dreams. They came like beautiful brown, shiny animals that didn’t know that they were alive, but lived. And when they ran and put their easy, lazy, timeless legs out and followed with their big sprawling arms and loose fingers, and smiled blowing in the wind, their expressions did not say, ‘Look at me run, look at me run.’ No, not at all. Their faces dreamily said ‘Lord, but it’s sure nice to run…’"

Many reviews of “The Big Black and White Game” commend Bradbury for writing a story about racial tensions. I also learned that the story was chosen for Best American Short Stories in 1945. This story provides a good example of the way a dated story can jar a reader. I had trouble reconciling the author of Fahrenheit 451 to the author of this story. (This experience is making me add The Martian Chronicles to my list. I’m ashamed to say that I’ve never read it, but I’ve always seen it characterized as a book that exposes prejudice and racism.)

The new edition of Golden Apples does not indicate that the reader is moving from the earlier The Golden Apples of the Sun to R is for Rocket, but it does include Bradbury’s 1962 introduction to the latter book. He writes: “This is a book then by a boy who grew up in a small Illinois town and lived to see the Space Age arrive, as he hoped and dreamt it would.” This “book” is much more cohesive than the earlier section containing the Golden Apples stories. It tells about rocket ships, space colonies, and time travel (intended and unintended, physical as well as mental). Many of the stories deal with family and space travel: “R is for Rocket” and “Rocket Man” charmingly demonstrate the sacrifices that families make when one of their members decides to travel to the stars; “The Strawberry Window” shows how colonists cope with being away from home. “The Sound of Thunder” is Bradbury’s eerie story that presents the “butterfly effect” though time travel. William Contento’s index lists this story as the most reprinted and anthologized science fiction story. “Frost and Fire” is a novelette-length story of survivors who crash on a planet with extreme temperatures and high radiation. At the beginning of the story, a boy, Sim, is born with all his faculties and senses intact. He has a clear racial memory telling him that he will grow and live and die in eight days. Bradbury’s structure and premise are strong here, and I found this story much more satisfying than many of the others.

The new edition of Golden Apples does not indicate that the reader is moving from the earlier The Golden Apples of the Sun to R is for Rocket, but it does include Bradbury’s 1962 introduction to the latter book. He writes: “This is a book then by a boy who grew up in a small Illinois town and lived to see the Space Age arrive, as he hoped and dreamt it would.” This “book” is much more cohesive than the earlier section containing the Golden Apples stories. It tells about rocket ships, space colonies, and time travel (intended and unintended, physical as well as mental). Many of the stories deal with family and space travel: “R is for Rocket” and “Rocket Man” charmingly demonstrate the sacrifices that families make when one of their members decides to travel to the stars; “The Strawberry Window” shows how colonists cope with being away from home. “The Sound of Thunder” is Bradbury’s eerie story that presents the “butterfly effect” though time travel. William Contento’s index lists this story as the most reprinted and anthologized science fiction story. “Frost and Fire” is a novelette-length story of survivors who crash on a planet with extreme temperatures and high radiation. At the beginning of the story, a boy, Sim, is born with all his faculties and senses intact. He has a clear racial memory telling him that he will grow and live and die in eight days. Bradbury’s structure and premise are strong here, and I found this story much more satisfying than many of the others.

In general, this collection seems uneven. There are great stories, weak stories, and dated stories—some are genre fiction; others are more mainstream. The R is for Rocket part is certainly stronger. The stories are better, and they seem to fit together. However, three of my four favorites come from the Golden Apple part of the book. These are “Sun and Shadow” and “The Fruit at the Bottom of the Bowl,” which are not science fiction stories at all, and “The Murderer,” which centers on technology in the “future” and seems very much like now. This book has made me want to read more Bradbury.

2011 Nebula Award Nominees

The SFWA has just announced the nominees for the 2011 Nebula Award. The nominees in the novel category are:

- Among Others – Jo Walton (Tor)

- Embassytown – China Miéville (Macmillan UK; Del Rey; Subterranean Press)

- Firebird – Jack McDevitt (Ace Books)

- God’s War – Kameron Hurley (Night Shade Books)

- Mechanique: A Tale of the Circus Tresaulti – Genevieve Valentine (Prime Books)

- The Kingdom of Gods – N.K. Jemisin (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

See the official press release for the complete list of award categories. Congrats to all the nominees! What do you think of this list? Any inclusions or omissions that surprise you?

2011 Bram Stoker Award Nominees

The final ballot for the 2011 Bram Stoker Award has been announced. The nominees in the novel categories are:

Novel

- A Matrix Of Angels – Christopher Conlon (Creative Guy Publishing)

- Cosmic Forces – Greg Lamberson (Medallion Press)

- Floating Staircase – Ronald Malfi (Medallion Press / Thunderstorm Books)

- Flesh Eaters – Joe McKinney (Pinnacle Books)

- Not Fade Away – Gene O’Neill (Bad Moon Books)

- The German – Lee Thomas (Lethe Press)

First Novel

- Isis Unbound – Allyson Bird (Dark Regions Press)

- Southern Gods – John Hornor Jacobs (Night Shade Books)

- The Lamplighters – Frazer Lee (Samhain Publishing)

- The Panama Laugh – Thomas S. Roche (Night Shade Books)

- That Which Should Not Be – Brett J. Talley (JournalStone)

Young Adult Novel

- Ghosts of Coronado Bay – J.G. Faherty (JournalStone)

- The Screaming Season – Nancy Holder (Razorbill)

- Rotters – Daniel Kraus (Delacorte Books for Young Readers)

- Dust Decay – Jonathan Maberry (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers)

- A Monster Calls – Patrick Ness (Candlewick / Walker)

- This Dark Endeavor – Kenneth Oppel (Simon & Schuster / David Fickling Books)

Congrats to all the nominees. See the complete list of nominees on the Horror Writers Association web site.

SF/F Quotes: Harlan Ellison

“

And so it goes. And so it goes. And so it goes goes goes goes goes tick tock tick tock tick tock and one day we no longer let time serve us, we serve time and we are slaves of the schedule, worshippers of the sun’s passing, bound into a life predicated on restrictions because the system will not function if we don’t keep the schedule tight.

”

— Harlan Ellison "’Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman" (1965)

Grand Master Reading Challenge January Review Winner: Mattastrophic

![]() The votes are in and the Grand Master Reading Challenge January review winner is Mattastrophic for his excellent review of The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin. Congratulations, Matt!

The votes are in and the Grand Master Reading Challenge January review winner is Mattastrophic for his excellent review of The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin. Congratulations, Matt!

For his effort Matt will receive a GMRC T-shirt, a GMRC button and a set of commemorative WWEnd Hugo Award bookmarks. Matt also got his choice of books from the WWEnd bookshelf. He picked Blackdog by K. V. Johanson (Pyr 2011). I hope we’ll be seeing a review of that one in future! Be sure to visit Matt at his blog, Strange Telemetry, for more SF/F reviews.

Of course Matt’s was not the only great review and we wouldn’t want our runners up to walk away empty handed. We’ll be sending out buttons and bookmarks to them as well.

A hearty thanks to everyone for helping us get the GMRC off to such a great start. Despite missing the first 10 days of the month you guys cranked out the books and reviews and very generously helped us spread the word on your blogs. February has started off strong too and we hope to have even more readers and reviewers joining in. If you have any friends that are up for a reading challenge the GMRC is one that you can easily catch up on if you miss the start. Let ’em know it’s not too late to sign up. There are more prizes to be won too so good luck to you all!

GMRC Review: A Time of Changes

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the second of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the second of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

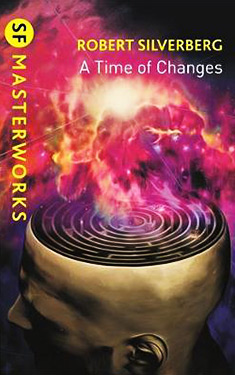

In the mid-1960s we find many established genre writers starting to produce more mature and more literary fiction, culminating – amongst other brave and ground-breaking concerns – in significant stories criticizing militarism and the neo-imperialism agendas of the then US foreign policy, a trend that reached its peak with Grand Master Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War. This novel swooped most of the awards at the time and expressed just how successful the New Wave’s ideological platform had been. Arguably, the legacy of the New Wave remains inconclusive, considering the still on-going debates about the supposed “ghettoization” of the genre. Robert Silverberg is an exponent of the New Wave. Initially a prolific writer of “routine” SF in the 1950s, he began to produce some of the most interesting works in SF during this period, such as Thorns, The Masks of Time, Tower of Glass and A Time of Changes, which went on to win the Nebula Award in 1971. I have never read it before now.

In the mid-1960s we find many established genre writers starting to produce more mature and more literary fiction, culminating – amongst other brave and ground-breaking concerns – in significant stories criticizing militarism and the neo-imperialism agendas of the then US foreign policy, a trend that reached its peak with Grand Master Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War. This novel swooped most of the awards at the time and expressed just how successful the New Wave’s ideological platform had been. Arguably, the legacy of the New Wave remains inconclusive, considering the still on-going debates about the supposed “ghettoization” of the genre. Robert Silverberg is an exponent of the New Wave. Initially a prolific writer of “routine” SF in the 1950s, he began to produce some of the most interesting works in SF during this period, such as Thorns, The Masks of Time, Tower of Glass and A Time of Changes, which went on to win the Nebula Award in 1971. I have never read it before now.

A Time of Changes is clearly a literary experiment. And – sadly, dare I say – very much a product of its time. Don’t get me wrong – I did like the book, but even recognising the fact that it is a story from its decade, I feel it’s quite dated.

It is a simple story that deals plausibly with a variety of complex issues. The setting is that of a future society on the planet Borthan, earlier colonised by members of a religious sect. They followed a set of theological guidelines called the Covenant, which prohibited one from opening your heart and mind to others, essentially then, the denial of self. It is meant to prevent individuals from placing their personal burdens on others, to the extent that a ban is placed on the use of first-person pronouns. Referring to one self as “I” is a terrible breach of manners and has both dire social and legal consequences. The act of “self-bearing” is the ultimate sin, as our narrator informs us himself:

Obscene! Obscene! Already on the one sheet I have used the pronoun “I” close to twenty times, it seems. While also casually dropping such words as “my”, “me”, “myself”, more often that I dare to count. A torrent of shamelessness. I I I I I. If I exposed my manhood in the Stone Chapel of Manneran on Naming Day, I would be doing nothing so foul as I am doing here. (Orb edition 2009, page 17-18)

We see that not everyone on Borthan embraces the Covenant. The opening sentence “I am Kinnall Darival and I mean to tell you all about myself” introduces the reader to someone who eventually came to resist the Covenant. Kinnall continues to relate his experiences from early childhood onwards to this exact point where he can write his self-bearing sentence. We meet him as a prince in the province of Salla, the younger son of the prime septarch on Borthan. Tradition dictates that he has little chance of becoming septarch himself and therefore he decides to leave his home upon his father’s death. He wanders for years before making a home in the southern province. Here Kinnall meets an earthman who challenges his early assumptions about his society and convinces him to take a wonder drug that breaks down the barriers between human minds through a telepathic experience. This act changes Kinnall from a staunch bureaucrat into a prophet of self-bearing, with some tragic consequences, and ultimately leads to his self-imposed exile in the Burnt Lowlands.

I generally enjoy this type of narrative, and was often reminded of Severian’s odyssey in Gene Wolfe’s seminal The Book of the New Sun. Silverberg does a splendid job with the internal conflicts of someone who challenges the very fabric of their society and comes to question the basis of their world and its religion. Kinnall is a strong, often courageous, inquisitive character and, judging by this first-person narrative, very introspective. But, like Severian, he is also notably fallible, appalingly arrogant and destructively selfish – these traits finally lead to an unexpected tragedy near the end as he proceeds to spread the drug and the new way of thinking about his world. Silverberg handles Kinnall’s downfall with consummate skill. One can be forgiven for equating this downward spiral to the predictable calamity of established drug addiction. Perhaps, in some preternatural sense, Silverberg has crafted an ingenious rebuke against the unchecked drug use of this period.

I do have some problems with the book. The Orb edition (2009) that features an explanatory, contextual preface by Silverberg, also, thankfully, had a map. Without this map, the lengthy descriptions of the geography of Borthan and the imaginary names would have been totally lost on me. Despite the wonderfully crafted world-building in true Silverberg tradition, it had little relevance for me to the story. Well, maybe Kinnall’s exile in the Burnt Lowlands and its accompanied descriptions is perhaps an exception, as symbolic of his downfall, the ultimate destination of his personal odyssey. A big part of the book is therefore little more than world exploration and adds to the surface appearance of just an elementary story about just another drug. Yes, Silverberg’s writing is exceptional, intriguing and euphonious, but it ultimately doesn’t save the story from all the tedious musings and descriptions. At times it felt dull and lackadaisical – the story could have done with some trimming. It never really shifted past first gear.

In the preface Silverberg does acknowledge that since the publication of A Time of Changes he discovered other languages that avoided the construct “I”. It might have appeared a unique literary device at the time, but let’s not forget that Samuel R. Delany has attempted the same in Babel-17. The story would have been so much stronger if Silverberg avoided using the construct “one” all together; it is nothing else but a mere replacement of the pronoun “I”. Why bother? People were still referring to themselves directly. It would have been less artificial if he remained within the constructs of what we experience with Kinnall’s forlorn journey into Glin, where people actively avoid speaking about themselves at all, not even using the term “one”. And it is quite acceptable to refer to someone else as “you”, which felt equally contrived, for – unless I’m mistaken – “you” still implies a concept of “self”.

In the preface Silverberg does acknowledge that since the publication of A Time of Changes he discovered other languages that avoided the construct “I”. It might have appeared a unique literary device at the time, but let’s not forget that Samuel R. Delany has attempted the same in Babel-17. The story would have been so much stronger if Silverberg avoided using the construct “one” all together; it is nothing else but a mere replacement of the pronoun “I”. Why bother? People were still referring to themselves directly. It would have been less artificial if he remained within the constructs of what we experience with Kinnall’s forlorn journey into Glin, where people actively avoid speaking about themselves at all, not even using the term “one”. And it is quite acceptable to refer to someone else as “you”, which felt equally contrived, for – unless I’m mistaken – “you” still implies a concept of “self”.

It is a one-sided story, a telling from only Kinnall’s perspective. Don’t expect the opponents of self-bearing to be more than pitiable, brain-washed victims who will never know the true happiness that comes from sharing yourself with others. The story lacks a strong counter-protagonist and suffers greatly because of it.

In the final analysis, if you are looking for epic and multifarious adventures in Hard SF this book is not going to appeal to you. It is predominately a detailed character study with alluring exploration of an alien world and equally strange society that asks obstinate questions about the world around us. The first chapter and middle part of the book is engaging and exciting – pure Silverberg world-building, the remainder weaker, even disappointing. I find the book an important achievement in the history of SF, for its attempt to move away from technological explorations and pulpy space adventures into the challenging sub-genre of Soft SF, exploring difficult psychological and philosophical issues – and can appreciate why it won a Nebula Award, clearly an attempt to recognize the principles of the New Wave generation. I can’t say I agree with Silverberg’s conclusion, though. Self-repression does not need to be replaced by self-annihilation and the appearance that total intimacy is the best way through which to create a peaceful, happy society, is very naïve, typical of the idealism from that era. The idea of totally opening up to others with a certain reckless wantonness and allowing them into our minds in order to study our innermost thoughts, feelings and concerns is more than a little incommodious.

I’m glad to have read the book, but wanted to like it more. Silverberg has written much better novels, many of which did not go on to win an award.

Sources: Edward James, Science Fiction in the 20th Century. Opus (1994); Robert Silverberg, "Preface" in A Time Of Changes, Orb (2009)

2011 Locus Recommended Reading List

Earlier this month Locus Magazine published its 2011 Recommended Reading List. "This recommended reading list, published in Locus Magazine’s February 2012 issue, is a consensus by Locus editors and reviewers…" of the best books published last year. These books make up the core of the Locus Awards Poll.

Earlier this month Locus Magazine published its 2011 Recommended Reading List. "This recommended reading list, published in Locus Magazine’s February 2012 issue, is a consensus by Locus editors and reviewers…" of the best books published last year. These books make up the core of the Locus Awards Poll.

We’ve just finished adding the missing novels to our database so you can’t say you have nothing new to read now. Check these out and let us know what you think of the list. What do you like on this list? Is there something missing that should be there? Dont’ worry, you can vote online until April 15th!

Novels – Science Fiction

- Daybreak Zero – John Barnes (Ace)

- Grail – Elizabeth Bear (Ballantine Spectra)

- Leviathan Wakes – James S. A. Corey (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- The Clockwork Rocket – Greg Egan (Night Shade Books)

- This Shared Dream – Kathleen Ann Goonan (Tor)

- 7th Sigma – Steven Gould (Tor)

- Deadline – Mira Grant (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- Earthbound – Joe Haldeman (Ace)

- 11/22/63 – Stephen King (Scribner; Hodder & Stoughton as 11.22.63)

- Wake Up and Dream – Ian R. MacLeod (PS Publishing)

- Firebird – Jack McDevitt (Ace)

- Embassytown – China Miéville (Ballantine Del Rey; Macmillan)

- All the Lives He Led – Frederik Pohl (Tor)

- The Islanders – Christopher Priest (Gollancz)

- Enigmatic Pilot: A Tall Tale Too True – Kris Saknussemm (Del Rey)

- Heart of Iron – Ekaterina Sedia (Prime Books)

- Rule 34 – Charles Stross (Ace; Orbit UK)

- Dancing With Bears – Michael Swanwick (Night Shade Books)

- The Children of the Sky – Vernor Vinge (Tor)

- The Courier’s New Bicycle – Kim Westwood (Voyager Australia)

- Zone One – Colson Whitehead (Doubleday; Harvill Secker)

- Vortex – Robert Charles Wilson (Tor)

- Home Fires – Gene Wolfe (Tor; PS)

Novels – Fantasy

- The Heroes – Joe Abercrombie (Gollancz; Orbit US)

- The Dragon’s Path – Daniel Abraham (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- Heartless – Gail Carriger (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- The Fallen Blade – Jon Courtenay Grimwood (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- The Alchemists of Kush – Minister Faust (Narmer’s Palette)

- Hidden Cities – Daniel Fox (Del Rey)

- The Uncertain Places – Lisa Goldstein (Tachyon Publications)

- Raising Stony Mayhall – Daryl Gregory (Del Rey)

- The Magician King – Lev Grossman (Viking)

- Redwood and Wildfire – Andrea Hairston (Aqueduct Press)

- The Kingdom of Gods – N. K. Jemisin (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- A Dance with Dragons – George R. R. Martin (Bantam; Harper Voyager UK)

- The Cold Commands – Richard K. Morgan (Ballantine Del Rey; Gollancz)

- Professor Moriarty: The Hound of the D’Urbervilles – Kim Newman (Titan Books)

- The Book of Transformations – Mark Charan Newton (Tor UK)

- Mr. Fox – Helen Oyeyemi (Picador UK; Riverhead)

- The Hammer – K. J. Parker (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- Snuff – Terry Pratchett (Harper; Doubleday UK)

- Briarpatch – Tim Pratt (ChiZine Publications)

- The River of Shadows – Robert V. S. Redick (Del Rey; Gollancz)

- The Wise Man’s Fear – Patrick Rothfuss (DAW; Gollancz)

- Deathless – Catherynne M. Valente (Tor)

- The Folded World – Catherynne M. Valente (Night Shade Books)

- Among Others – Jo Walton (Tor)

- Mistification – Kaaron Warren (Angry Robot UK; Angry Robot US)

Young Adult Books

- Abarat: Absolute Midnight – Clive Barker (Harper; HarperCollins UK)

- The Mostly True Story of Jack – Kelly Barnhill (Little, Brown)

- Chime – Franny Billingsley (Dial)

- Red Glove – Holly Black (McElderry)

- Beauty Queens – Libba Bray (Scholastic)

- Eona – Alison Goodman (Viking; Angus & Roberson)

- Twilight Robbery – Frances Hardinge (Macmillan; Harper as Fly Trap)

- The Shattering – Karen Healey (Allen & Unwin; Little, Brown)

- Huntress – Malinda Lo (Little, Brown)

- Planesrunner – Ian McDonald (Pyr)

- A Monster Calls – Patrick Ness (Walker UK; Candlewick)

- The Akata Witch – Nnedi Okorafor (Viking)

- Mastiff – Tamora Pierce (Random House)

- Scrivener’s Moon – Philip Reeve (Marion Lloyd)

- Across the Universe – Beth Revis (Razorbill)

- Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children – Ransom Riggs (Quirk)

- The Freedom Maze – Delia Sherman (Small Beer Press/Big Mouth House)

- The Highest Frontier – Joan Slonczewski (Tor)

- Daughter of Smoke and Bone – Laini Taylor (Little, Brown; Hodder & Stoughton)

- The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making – Catherynne M. Valente (Feiwel and Friends)

- The Boy at the End of the World – Greg van Eekhout (Bloomsbury USA)

- Goliath – Scott Westerfeld (Simon Pulse; Simon & Schuster UK)

- Across the Great Barrier – Patricia C. Wrede (Scholastic)

- The Space Between – Brenna Yovanoff (Razorbill)

First Novels

- Debris – Jo Anderton (Angry Robot US; Angry Robot UK)

- The Girl of Fire and Thorns – Rae Carson (Greenwillow; Gollancz as Fire and Thorns)

- Ready Player One – Ernest Cline (Crown; Century)

- God’s War – Kameron Hurley (Night Shade Books)

- The Desert of Souls – Howard Andrew Jones (St. Martin’s)

- Of Blood and Honey – Stina Leicht (Night Shade)

- Soft Apocalypse – Will McIntosh (Night Shade Books)

- The Night Circus – Erin Morgenstern (Doubleday)

- The Tiger’s Wife – Téa Obreht (Random House; Weidenfeld & Nicholson)

- Low Town – Daniel Polansky (Doubleday; Hodder & Stoughton as Low Town: The Straight Razor Cure)

- Mechanique: A Tale of the Circus Tresaulti – Genevieve Valentine (Prime Books)

- Blood Red Road – Moira Young (McElderry; Marion Lloyd)

- Seed – Rob Ziegler (Night Shade Books)

GMRC Review: Prelude to Space by Arthur C. Clarke

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his second for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his second for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

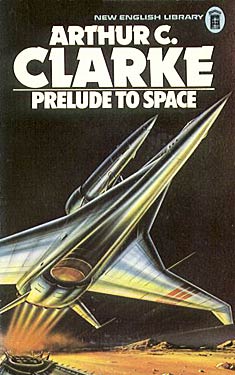

Prelude to Space by Arthur C. Clarke is my second read in the 2012 WWEnd Grand Master Reading Challenge. Last month I read Poul Anderson‘s Tau Zero (1970), which is one Anderson’s better known novels. For my second read I picked something a little less high profile. Prelude to Space is the first novel Arthur C. Clarke wrote and is generally not considered as good as Childhood’s End (1953), probably the most famous of Clarke’s early novels. The publication history of this story is not unusual for the period. Clarke wrote the novel in the space of a month in 1947 but it wasn’t until 1951 that the whole novel was published in magazine format by Galaxy Science Fiction. It was followed by a hardcover edition in 1953. What is atypical about it, is that the novel does not appear to be based on one of Clarke’s short stories. Although one of Clarke’s lesser works, it has been reprinted numerous times. The edition I have read was printed in 1977 and includes a "Post Apollo Preface", as Clarke himself puts it, written in 1969.

Prelude to Space by Arthur C. Clarke is my second read in the 2012 WWEnd Grand Master Reading Challenge. Last month I read Poul Anderson‘s Tau Zero (1970), which is one Anderson’s better known novels. For my second read I picked something a little less high profile. Prelude to Space is the first novel Arthur C. Clarke wrote and is generally not considered as good as Childhood’s End (1953), probably the most famous of Clarke’s early novels. The publication history of this story is not unusual for the period. Clarke wrote the novel in the space of a month in 1947 but it wasn’t until 1951 that the whole novel was published in magazine format by Galaxy Science Fiction. It was followed by a hardcover edition in 1953. What is atypical about it, is that the novel does not appear to be based on one of Clarke’s short stories. Although one of Clarke’s lesser works, it has been reprinted numerous times. The edition I have read was printed in 1977 and includes a "Post Apollo Preface", as Clarke himself puts it, written in 1969.

In the year 1978 humanity is ready to for the next step in exploration, the first manned mission to the Moon is about to leave Earth. Historian Drik Alexson is sent to London, where the headquarters of Interplanetary, the non-profit organization coordinating the mission, is located. He is to document the event, that will no doubt be considered one of the turning points in human history. Although Alexson is supposed to be an impartial observer, he can’t help but by swept away by the magnitude of the effort and the impact it will have on human society. As the launch date nears, Alexson realizes that this event will be his life’s work as a historian.

Although science fiction is much more about exploring ideas and what they might mean to society than actually predicting the future, seeing how many details Clarke got wrong in this novel is still almost as interesting as the story itself. Where Clarke goes for private enterprise as the driving factor and assumes the memory of the Second World War will change the way people see armed conflict, in reality is was the tension between East and West that gave space exploration a huge boost. The need for the US to prove it could outdo their Soviet rivals resulted in a moon landing nine years before the one Clarke describes, using very different rockets to get there. Many of Clarke’s novels describe futures where science, logic and reason triumph over the petty squabbles, religious dogmas and ideological differences to achieve a peaceful and stable way of running the planet. In Prelude to Space this is treated as inevitable. Would that Clarke had been right on that point.

Another thing that struck me about Clarke’s scenario is the use of atomic energy to power these rockets. These days, radioactivity makes people very nervous, and rightly so as recent events in Fukushima have shown us. Some horrendous experiments were carried out testing nuclear devices in the 1950s, clearly showing that the long term impact of radioactive substances released into he environment was still very poorly understood at the time this novel was written. The radioactivity around the launch site in the Australian desert is mentioned several times but not considered a matter of great concern. It might be technically possible to limit the risk of radioactive contamination, even in the event of a launch failure, but somehow I think it would be very hard to convince the general public that it’d be safe these days.

Clarke’s futures are generally pretty optimistic, sometimes even utopian, and this novel is no exception. Prelude to Space is something of a cross between a love letter to and an advertisement for space exploration. Clarke carefully connects the historical desire to travel to the stars, early science fiction and lots of technological developments, all leading to this one momentous occasion. The moment when humanity will finally leave its cradle and first set foot on a strange world. A first step on a path from which there will be no turning back. Where that path will lead, Clarke doesn’t dare predict but he seems to be quite sure it is one we must take to ensure survival of the species. The author may overdo it a little in the text but his enthusiasm is contagious. It was almost enough to make me wonder why the hell we are not on our way to Mars already.

Clarke’s futures are generally pretty optimistic, sometimes even utopian, and this novel is no exception. Prelude to Space is something of a cross between a love letter to and an advertisement for space exploration. Clarke carefully connects the historical desire to travel to the stars, early science fiction and lots of technological developments, all leading to this one momentous occasion. The moment when humanity will finally leave its cradle and first set foot on a strange world. A first step on a path from which there will be no turning back. Where that path will lead, Clarke doesn’t dare predict but he seems to be quite sure it is one we must take to ensure survival of the species. The author may overdo it a little in the text but his enthusiasm is contagious. It was almost enough to make me wonder why the hell we are not on our way to Mars already.

This is the tenth novel by Clarke I have read, spanning his entire career, and from those it seems obvious that Clarke didn’t change his approach to writing a whole lot during his seven decades as a published author. Some sections of the novel are highly technical, with the science of space travel the main character. Alexson is the vehicle that allows Clarke to show the events leading up to the launch from up close, but he seems to have very little interest in the man himself (perhaps not altogether surprising, he strikes me as a bright but not very interesting fellow). You don’t read Clarke for his well rounded characters or complex plots but for the hard science and Clarke’s visions of what they may mean for future society.

Sixty-five years after it was written Prelude to Space is badly dated in just about every aspect of the story. From the technical developments to the blatant sexism that plagued science fiction in those days. On top of that, Clarke wrote a novel that reads like propaganda for a space program. It is very effective propaganda though. Despite all the novel’s flaws, you can’t help but be caught up in the excitement of the enterprise and the possibilities of space travel, many of which still haven’t been realized. Clarke’s optimism has been proven unfounded in some ways but the drive to explore space is still there. This novel might well have been an inspiration to some teenager in the 1950s to pursue a career in physics or astronomy. Clarke has gone on to write more challenging novels but for a debut, it’s a decent read.

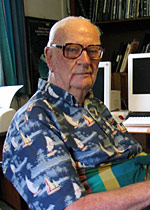

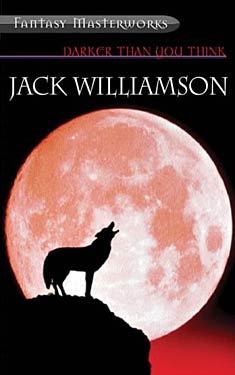

GMRC Review: Darker Than You Think by Jack Williamson

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s second GMRC review.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s second GMRC review.

Newspapermen and one gorgeous, redheaded, green-eyed newspaperwoman wait on the chilly tarmac of the Clarendon airport for the chartered plane returning the Lamarck Mondrick expedition from their two your stint in Nala-Shan. (Nala-shan actually exists. It’s a mountain range in Northern China between Ninxgia and inner Mongolia’s Alxa League. This could be the only trace of verifiable fact Williamson brings to his novel.) Along with the press are family members of the four returning explorers, including the elderly, stately Rowena Mondrick, blind since a panther ripped out her eyes in Nigeria some years before.

Newspapermen and one gorgeous, redheaded, green-eyed newspaperwoman wait on the chilly tarmac of the Clarendon airport for the chartered plane returning the Lamarck Mondrick expedition from their two your stint in Nala-Shan. (Nala-shan actually exists. It’s a mountain range in Northern China between Ninxgia and inner Mongolia’s Alxa League. This could be the only trace of verifiable fact Williamson brings to his novel.) Along with the press are family members of the four returning explorers, including the elderly, stately Rowena Mondrick, blind since a panther ripped out her eyes in Nigeria some years before.

Mark Barbee is there, an old friend of the explorers and now an alcoholic reporter for the Star. He introduces himself to the beautiful readhead, April Bell, novice reporter for Clarendon’s rival newspaper. She carries a small snakeskin bag that holds an adorable black kitten. Don’t get too attached to the kitten.

The plane lands, the much aged and visibly frightened explorers descend the ramp. They carry a heavily locked green case. The enfeebled Mondrick begins a speech, promises world-shattering revelations, then dies of asthma or a heart attack or a combination of the two, Much consternation. April Bell vanishes, but Matt Barbee has already made a date for later that night. His nose for news leads him to a dumpster near the airport terminal where he finds the snakeskin bag containing the kitten. It’s been strangled by a red ribbon and it’s heart punctured by an ivory pin decorated with a running wolf. It must be that same nose for news that does not make Barbee consider canceling his date.

This is the set-up for Jack Williamson‘s Darker Than You Think. (Oh, in case you need more clues to coming events, Rowena Mondrick drapes herself in silver jewelry and her mastiff, wearing a silver-studded collar, goes beserk when he sees April Bell.)

Williamson’s novel first appeared in John W. Cambell’s Astounding in 1940 as a 40,000 word serial. After WWII, the market for science fiction changed. Pulps were losing out to radio and paperbacks, but the now grown-up kids who loved sf from its pulpy origins wanted to see the stories in book form. Lloyd Arthur Eschbach founded Fantasy Press in 1946 and brought out Williamson’s The Legion of Space. Respectable sales prompted Llyod to ask Williams to double the length of Darker Than You Think, and its sales equaled those of the previous novel. It’s been reprinted many times. The edition I read was a Dell 1979 paperback that reproduced the original drawings by Edd Cartier, whose work, according the book’s blurb, adds an extra dimension of enjoyment. Well, maybe. Certainly it adds an extra dimension of camp. My favorite is the frontispiece that features a nude woman seated on the back of a sabre-tooth tiger. She has the perky but nipple-free breasts not uncommon to illustrations of the time.

April Bell is a witch, part of the Old Breed that Mondrick wants to eliminate from the earth. Barbee, it turns out, is a shapeshifter himself. I thought is was cheating to have them turn invisible when they took animal form, but it is necessary to make the plot work. Because Williamson wanted to write science fiction and not occult fantasy, he provides some anthropological background for this demon breed and some fanciful physics for why they can walk through walls. This theory is put forth at length several times in dialogue that bears no hint of realistic human speech.

April Bell is a witch, part of the Old Breed that Mondrick wants to eliminate from the earth. Barbee, it turns out, is a shapeshifter himself. I thought is was cheating to have them turn invisible when they took animal form, but it is necessary to make the plot work. Because Williamson wanted to write science fiction and not occult fantasy, he provides some anthropological background for this demon breed and some fanciful physics for why they can walk through walls. This theory is put forth at length several times in dialogue that bears no hint of realistic human speech.

Williamson lists this among his favorite books because it embodied much of what he learned about himself in psychoanalysis. He had been selling erractically to the pulps for years, but in 1936 he hit a wall. (He was 28.) He had been reading about psychiatry and wrote Ives Hendricks , the author of Facts and Theories of Psychoanalysis about coming to Boston from New Mexico for treatment. Hendricks suggested the Menninger Clinic in Topeka and Karl Menniger agreed to see him on April 13. With enough money to live frugally in Topeka, even paying the five dollars an hour for treatment, Williamson stayed. He was under the treatment of Dr. Charles W. Tidd, until two years kater when money ran out and he and his doctor agreed there was nowhere further to go at the time.

In Darker Than You Think Topeka becomes Clarendon. Glennhaven is an enormous and very active psychiatric hospital where Barbee makes a brief stay. There is too much plot to keep him there for any length of time. What Williamson learned with Dr. Tidd at the Menninger was to let go of some of his inner conflicts and accept parts of himself he had attempted to keep rigidly separated. How this works out for Barbee in the novel some readers found shocking.

Darker Than You Think is enjoyable but dated and creaky. Here is a clue to how you might enjoy it more. Imagine it as a black and white movie from RKO studios in the 1940’s, produced by Val Lewton and directed by Jacques Tourneur. That is if you want to emphasize the moodier aspects. For a crisper image turn the project over to Robert Wise.

(All the biographical information in this review comes from Williamson’s memoirs, Wonder’s Child: My Life In Science Fiction.)

Bilbo’s Last Song

As part of our ongoing effort to underscore the classier side of genre literature, we continue our Genre Poetry series with a selection from J.R.R. Tolkien.

As part of our ongoing effort to underscore the classier side of genre literature, we continue our Genre Poetry series with a selection from J.R.R. Tolkien.

Bilbo’s Last Song (At the Grey Havens)

by J.R.R. TolkienDay is ended, dim my eyes,

But journey long before me lies.

Farewell, friends! I hear the call.

The ship’s beside the stony wall.

Foam is white and waves are grey;

beyond the sunset leads my way.

Foam is salt, the wind is free;

I hear the rising of the sea.Farewell, friends! The sails are set,

the wind is east, the moorings fret.

Shadows long before me lie,

beneath the ever-bending sky,

but islands lie behind the Sun

that I shall raise ere all is done;

lands there are to west of West,

where night is quiet and sleep is rest.Guided by the Lonely Star,

beyond the utmost harbour-bar,

I’ll find the heavens fair and free,

and beaches of the Starlit Sea.

Ship my ship! I seek the West,

and fields and mountains ever blest.

Farewell to Middle-earth at last.

I see the star above my mast!

Full Details

Full Details