GMRC Review: Stepsons of Terra by Robert Silverberg

Chris Uhl (chuhl) can’t remember a time when he wasn’t a science fiction fan. He has a B.A. in Classics from Vassar College and an M.A. in English Literature from the University of Virginia. He has worked as a teacher, a legal assistant, a college development officer, a salesman, and a film extra. Chris may be the only WWEnd reviewer who has no blog. This is his third GMRC review to feature in the WWEnd blog.

Chris Uhl (chuhl) can’t remember a time when he wasn’t a science fiction fan. He has a B.A. in Classics from Vassar College and an M.A. in English Literature from the University of Virginia. He has worked as a teacher, a legal assistant, a college development officer, a salesman, and a film extra. Chris may be the only WWEnd reviewer who has no blog. This is his third GMRC review to feature in the WWEnd blog.

Stepsons of Terra is the story of Baird Ewing, a man on a mission to save his planet. His homeworld, a distant colony of Earth, lies in the path of implacable alien invaders. He travels to Earth, the first of his people to do so in 500 years, to get help, but he is shocked to find that Earthmen are not the resourceful supermen he was expecting. Instead they are weak, decadent and about to succumb to invasion themselves at the hands of the Sirians.

Like one of Alfred Hitchcock’s heroes, Ewing runs afoul of the Sirians, who refuse to believe the simple truth that he has come to enlist Earth’s help. They jump to the wrong conclusion and assume that Ewing has come to lead a revolution to save Earth so they harass, kidnap, and torture him.

In his introduction, Silverberg says that this novel, his sixth, is the first one in which “I was a trifle less flamboyant about making use of the pulp-magazine clichés [such as] feudal overlords swaggering about the stars. Rather, I would write a straightforward science fiction novel, strongly plotted but not unduly weighted towards breathless adventure.”

GMRC Review: The Stochastic Man by Robert Silverberg

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s fourth GMRC review to feature in our blog.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s fourth GMRC review to feature in our blog.

Robert Silverberg considered The Stochastic Man a valedictory offering. When he wrote the novel in the early 1970’s he had already resolved to effect his second retirement from the world of science fiction. His first retirement came around 1958, the year the science fiction magazine world imploded due to over-saturation and the growing market for paperback books. Writer and editor Frederik Pohl brought Silverberg back into the sf fold in the early 1960’s, encouraging him to write more thoughtful material than the pulp-influenced novels and stories he cranked out–and Silverberg would not himself object to that characterization–during the previous decade. But then, by the 1970’s, Silverberg discovered that he was "on the wrong side of a revolution." He joined in with the new crowd of younger writers, J. G. Ballard, Thomas M. Disch, Samuel R. Delany and others, who were producing more literary and experimental fiction. ("Younger" is a relative term here. Silverberg himself was only in his thirties at this time, but he had been publishing since he was nineteen.) This period, from 1965 – 1974, is considered to be Silverberg’s best, but he saw his readership drying up.

"What was fun for the writers, though, turned out to be not so much fun for majority of the readers, who justifiably complained that if they wanted to read Joyce and Kafka they would go and read Joyce and Kafka. They didn’t want their sf to be Joycified or Kafkaized. So they stayed away from the new fiction in droves, and by 1972 the revolution was pretty well over."

Silverberg also cites the pernicious influence of Star Wars and the craze for trilogies on the popular sf market. He considered himself out of the game and simply fulfilling contractual commitments when he wrote The Stochastic Man and Shadrach in the Furnace, published in 1975 and 1976 respectively.

The Stochastic Man may not be the worst title ever given an sf novel, but forty years later it is unappealing, opaque, and dated. Silverberg gives a history and definition of the term in the opening chapter. It comes from logic and mathematics and figures in writing on computer theory. I associate it with the titles of text books and academic monographs filled with symbols and formulas I will never understand. On the practical level, it refers to using sophisticated sampling methods to gather a large enough pool of variables to proceed to an educated guess. Sexy stuff, right? In the 1970’s it must have had buzzword novelty. I ran it through Google’s NGram viewer that tracks a term’s popularity. "Stochastic" makes a steady climb from near total obscurity in 1950 to a high point in 1990 and then, after a period of stasis, there is a decline beginning at the turn of the century. In the 1970’s it was definitely on the rise. Silverberg’s novel takes place in the 1990’s, so when Lew Nichols defines himself as a stochastician, he is using a trendy 1970’s term to describe a profession that sounds very much like what we would call a consultant, no frills attached.

The 1970’s permeates Siverberg’s near future narrative. New York City at the turn of the millennium is the worst case scenario of what New York in the early 1970’s was becoming. With the successful Disneyfication of Times Square and the city’s declining crime rates it is hard to remember that forty years ago New York City was dirty, dangerous, and nearing bankruptcy. Silverberg and his wife were both lifelong New Yorkers, but they had, like many of their friends, decamped for the West Coast by the time he wrote this novel. In Lew Nichol’s New York City, Puerto Rican and Black populations stage pitched battles. Large portions of the city are too dangerous to enter, and those who can afford them travel with protective devices that ward off attackers. The nicest, newest and safest buildings are on Staten Island while the Upper East Side is livable but crumbling. All but the finest restaurants serve artificial food.

But Lew and his wife Sundara, a glamorous woman of Indian origin, live the good life. Lew’s stochastic firm brings in an enviable income, as does Sundara’s art gallery. (Hmm, a wealthy man whose wife runs an art gallery. Silverberg got that one right.) They attend exclusive parties where the elite mingle and choose sexual partners for later in the evening. A variety of legal drugs keep the party going.

"The terrors and traumas of New York City seemed indecently remote as we stood by our long crystalline window, staring into the wintry moonbright night and seeing only our own reflections, tall fairhaired man and slender dark woman, side by side, side by side, allies against the darkness… Actually neither of us found life in the city really burdensome. As members of the affluent minority we were isolated from much of the crazy stuff…"

So what is this novel actually about? Reviewers need not worry about spoilers, since a dozen pages into it Lew Nichols, as first-person narrator, has revealed most of the plot developments. Lew will become a consultant to the political campaign of the charismatic Paul Quinn, the great hope of a city and country seeking to rejuvenate itself, but who Lew describes as "potentially the most dangerous man in the world." He imagines that American voters dream of being able to withdraw the votes that as Lew is telling the story they will not place for another four or five years. And there is the enigmatic character of Martin Carvajal, a milquetoast multimillionaire who goes beyond Lew’s stochastic methods and is able to literally see the future. Lew calls him a "wild card in the flow of time." Carvajal’s resigned, passive nature comes from not only the fact that for him the future and history are one and the same, but he is also aware of the exact moment of his rapidly approaching violent death. He wants to bring Lew on as a pupil in seeing the future, rather than simply making educated guesses about it.

Revealing all in the first chapter of a book sets up a classic suspense structure where readers stay with the story to see how the inevitable works itself out. But Silverberg’s profoundly pessimistic novel is not about keeping you on the edge of your seat. By revealing so much early on, the reader becomes, like Carvajal and increasingly like Lew, one that can only watch inexorable events unspool like the frames of a film. More or less knowing what’s coming makes all the political machinations and messy personal relationships objects of detached interest rather than elements in an engaging plot. The Stochastic Man is a stylistic exercise that is likely to leave many readers cold, but I found it the most interesting though not the best Silverberg novel I have read.

Revealing all in the first chapter of a book sets up a classic suspense structure where readers stay with the story to see how the inevitable works itself out. But Silverberg’s profoundly pessimistic novel is not about keeping you on the edge of your seat. By revealing so much early on, the reader becomes, like Carvajal and increasingly like Lew, one that can only watch inexorable events unspool like the frames of a film. More or less knowing what’s coming makes all the political machinations and messy personal relationships objects of detached interest rather than elements in an engaging plot. The Stochastic Man is a stylistic exercise that is likely to leave many readers cold, but I found it the most interesting though not the best Silverberg novel I have read.

And what is this obsession with knowing the future beyond the ability to choose lottery numbers and hot stocks? Carvajal’s resignation and depression should clue Lew in on the fact that foreknowledge does nothing but make you a passive agent of the inevitable. But like 17th century Puritans struggling with the paradoxes of predestination and free will, Lew cannot let go of his obsession with seeing. (Silverberg italicizes the term throughout the book.) At the end of the novel–and this would be a spoiler except it too is described in the opening chapter–Lew has inherited Carvajal’s millions and used them to set up an institute to develop the talent for second sight in as many people as possible. He still thinks this is a meaningful project. I thought he hadn’t read his own book.

(Biographical information in this review comes from Silverberg’s Other Spaces Other Times.

GMRC Review: Shadrach in the Furnace by Robert Silverberg

Carrie Naughton (Bookkeeper), can’t settle down. She has lived all over the US and worked as a retail clerk, short order cook, librarian, teaching assistant, farm apprentice, and office manager. For the past six years she’s been slow-roasting in Tucson, Arizona, dividing her life between bookkeeping by day and book writing by night. An astrologist once summed up Carrie’s stars by dubbing her a Hermit Opportunist. Too true. Check out her wee fledgling blog at hermitopportunist.tumblr.com.

Carrie Naughton (Bookkeeper), can’t settle down. She has lived all over the US and worked as a retail clerk, short order cook, librarian, teaching assistant, farm apprentice, and office manager. For the past six years she’s been slow-roasting in Tucson, Arizona, dividing her life between bookkeeping by day and book writing by night. An astrologist once summed up Carrie’s stars by dubbing her a Hermit Opportunist. Too true. Check out her wee fledgling blog at hermitopportunist.tumblr.com.

Editor’s Note: This review was posted in May be we missed adding it to the blog so it’s now our first June review.

I was pleasantly surprised to find Shadrach in the Furnace a page-turner with vivid characters. I expected it to be dull and dreary, but instead there’s suspense, a noble hero, and lots of sex!

I was pleasantly surprised to find Shadrach in the Furnace a page-turner with vivid characters. I expected it to be dull and dreary, but instead there’s suspense, a noble hero, and lots of sex!

That said, the plot is slightly transparent, and the ending comes a little too quickly, but this near-future dystopian story of an ailing despot, Genghis II Mao IV Khan (oh, just call him the Khan), and his personal physician, Shadrach Mordecai, pulls the reader into an enjoyable, if mild, parable of intrigue, betrayal and quiet heroism. The story hinges on whether or not the Khan will use his cadre of doctor-scientists to transfer his consciousness (or is it his soul?) into the body of Shadrach, and continue living forever while the people of his kingdom, plagued by a disease called organ rot, wait for a cure that is available, but will never be distributed if the Khan continues to reign.

Silverberg‘s use of present tense, which can often be jarring and annoying, here works fluidly, turning the narrative into a kind of sly, urgent aside. The prose reveals the dual nature of Shadrach: his responsiveness as a doctor (and a lover), and his calm, aloof personality. Despite the fact that as part of his position as royal doctor, his body has been implanted with a full range of bio-sensors that attune him to every fluctuation of the Khan’s failing systems, Shadrach possesses a yogic calm (maybe a little too calm – and how come those body sensors never cause him to experience sex from the Khan’s physical perspective?) from the first chapter, when we meet him as caregiver for the dictator, to the end, when he becomes caregiver for the human race.

The novel has a richness to it that you don’t find in too many old dystopian novels, and I think it’s partly because of the vivid allusions to religious history (whether cliched or not – Shadrach’s form of meditation happens to be carpentry) and the global settings. Most post-apocalyptic novels I’ve read take place in a battered America, but Shadrach’s tale spans the globe. And it must be pointed out that you don’t come across too many science fiction heroes in the form of young black men.

Shadrach’s bedroom romps with his two paramours (a man like Shadrach – beautiful, strong, intelligent – of course finds himself linked to two different women, both fierce and flawed) deepen what could have been a boring futuristic medical thriller. A good many racy boudoir scenes provide Silverberg with the opportunity to keep the reader turning pages but also to play upon archetypes and stereotypes (sometimes unsuccessfully). It’s the Valkyrie versus Pocahontas. One of these women will disappoint Shadrach, and one will surprise him.

Shadrach’s bedroom romps with his two paramours (a man like Shadrach – beautiful, strong, intelligent – of course finds himself linked to two different women, both fierce and flawed) deepen what could have been a boring futuristic medical thriller. A good many racy boudoir scenes provide Silverberg with the opportunity to keep the reader turning pages but also to play upon archetypes and stereotypes (sometimes unsuccessfully). It’s the Valkyrie versus Pocahontas. One of these women will disappoint Shadrach, and one will surprise him.

There’s also some hypnosis-induced recreation in the form of "dream-death," which is a kind of hallucinatory self-discovery vacation for the non-diseased elite. In a different story, this kind of Huxleyed up mind trip might be overblown and contrived. But the character of Shadrach keeps the story grounded.

Overall, not a bad tale, and surprisingly hip.

GMRC Review: Dying Inside by Robert Silverberg

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his third for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his third for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Robert Silverberg must be one of the most prolific authors in Science Fiction. I’m not sure if there is such a thing as a complete bibliography on the web but the ones I’ve seen rival those of Isaac Asimov. Since the 1950s Silverberg has written science fiction, fantasy, soft-pornography, non-fiction, countless short stories and edited shelves of anthologies. A quick search turns up at least two dozen pseudonyms. Not all of his output is highly regarded. Especially the early works, a period during which Silverberg was basically writing as fast as he could and selling his material to pulp magazines, are considered of lesser quality. Dying Inside (1972) was written during a later period in his career, lasting from the late 1960s till his first retirement in 1975. During those years Silverberg produced some his most celebrated science fiction novels. Works in which he takes a more literary approach than earlier in his career.

David Selig is a middle aged man living in New York. When we first meet him, he is making a living selling term papers to Columbia University students, a place where he once studied himself. David is not a happy man, for the last few years he’s been feeling his talent to read people’s minds fading. It is a talent that brought him an unhappy childhood as well as immense grief and countless problems in his personal life over the years, but also one that defines him as a person. Now that it is slipping away from him, he feels he is dying inside.

For a Science Fiction novel, the story contains very few speculative elements. Selig is a powerful telepath but that is just about the only thing science fictional to it. The novel is a character study of Selig, quite introspective and entirely focused on his struggles with his talent and accepting his loss of it. The author plays with memories and flashbacks in the novel, eventually covering most of Selig’s life. Maybe this lack of action and the less plot driven character of the novel are the reason why it didn’t win any of the awards it was nominated for. It was nominated for the Nebula, Hugo and Locus awards, all three of which ended up being won by Isaac Asimov’s The Gods Themselves. I haven’t read that book, but from the description I’d say it is a bit more in line with what readers would have expected from a science fiction novel in the 1970s.

Selig is obsessed with literature, poetry, plays, classical music and philosophy and Silverberg stuffs in a lot of references to famous works of art in the story. I’ve always found it interesting that a science fiction novel is much more likely to contain such references to the classics of literature than the other way around. Silverberg included one of Selig’s papers on the works of Franz Kafka for instance. Which is not only a reference to one of his literary influences but also an example of the different styles of writing we find in the novel. The author also includes letters and has Selig talk to himself in the second person in an attempt to distance himself from some of his more shameful acts. The shifts between different phases of Selig’s life, in combination with the different styles of narrative, help keep things interesting.

At several points in the novel I wondered how much of the story is autobiographical. There are some similarities between Selig and Silverberg. Both from Brooklyn, both studied at Columbia, both with an intense interest in literature. I haven’t come across any biographies that mention Silverberg being Jewish but, given his name, it is certainly possible. A writer peering into the head of his characters (or his own head if you support the idea that all characters are some aspect of the author) is not that different from reading the mind of the people around you. Selig seem to make the link between the loss of his talent and his diminishing sexual prowess. More than one critic has pointed out the parallel between the loss of Selig’s talent and Silverberg’s loss of joy in the creative process. Something that apparently appears in different forms in other novels from this period and may have contributed to his first retirement. It sounds plausible to me but given my unfamiliarity with Silverberg’s work I have no idea how accurate it is.

Selig is a very depressing character during most of the book. His life is an unhappy one. He thinks of his talent as a curse most of the time although loosing it upsets him greatly as well. Reading the minds of others is often painful to him. Their true opinion and motives are completely clear to him and it often includes things he’d rather not hear about himself. He finds it almost impossible to start a relationship with a women when he can read her mind and the few times that he does try, it inevitably ends in disaster. One of he most telling examples of Selig’s problems with his talent is when he takes a peak in the mind of the woman he is making love to and finds she can spare not a single thought about him when she is about to climax. Not entirely unexpected perhaps, but it is a devastating experience nonetheless. It is the leitmotiv of his life I guess, people don’t really want to know the truth of what other people think of them and Selig shows us why. They shade the truth, hedge or outright lie in order to function socially. I do wonder if the emphasis Selig puts on the ugly things he finds in the minds of those around him isn’t a bit overdone. Do doubts, fears, distaste and anger really outweigh the positive things that must be present in a person as well? His reaction to knowing what people think may say more about Selig himself than the people he reads.

I guess it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Selig’s talent can be used for personal gain. Selig does so himself in various, usually petty ways but not until he meets Tom Nyquist does he realize the full extend of what is possible. Nyquist is the only other character we meet that has David’s talent and he is quite unapologetic about it. He makes lots of easy money on Wallstreet with inside trading and is not adverse to using his talent to manipulate people. Selig is amazed and repulsed by his style of living, Nyquist’s life is one of luxury but Selig feels it is empty and ends up disgusted with him. Embracing his talent in that way makes Nyquist a lot more comfortable with himself than Selig is however, and to Selig, Nyquist can’t lie about that.

I guess it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Selig’s talent can be used for personal gain. Selig does so himself in various, usually petty ways but not until he meets Tom Nyquist does he realize the full extend of what is possible. Nyquist is the only other character we meet that has David’s talent and he is quite unapologetic about it. He makes lots of easy money on Wallstreet with inside trading and is not adverse to using his talent to manipulate people. Selig is amazed and repulsed by his style of living, Nyquist’s life is one of luxury but Selig feels it is empty and ends up disgusted with him. Embracing his talent in that way makes Nyquist a lot more comfortable with himself than Selig is however, and to Selig, Nyquist can’t lie about that.

Another striking thing about Selig’s view on the world is how much it revolves around sex. It motivates our actions to a much greater extend than many people would be comfortable admitting but since Selig tends to see right through others, it is very much exposed to him. Finding partners is rarely a problem for him since he knows for certain who is available and interested. Which of course takes something of the thrill of the chase away. Where sexual attraction or desires are mostly kept hidden for others, something not discussed openly or at best considered very private, it is completely exposed to Selig from a young age. It gives him a unique perspective on these matters and Silverberg is not afraid to expose his readers to it. He succeeds in showing the reader why this is as uncomfortable to Selig as it is to his surrounding.

I can see why this is a notable book among it’s contemporaries. Silverberg approaches the novel in a way you don’t see a lot in science fiction novels. It is a pretty dark and introspective book. I’m not sure everybody will appreciate the ending but I thought it was fitting. Dying Inside is a book that can make the reader uncomfortable by laying bare the innermost thoughts and feelings of the characters. It usually isn’t pretty, but like it or not, most of us will recognize a lot in what Selig is exposed to. I can see why this novel is one of the more highly regarded novels of the period. Some Science Fiction novels age badly. In some ways this is a novel of its time but certainly highly readable today. I’m going to have to read some more Silverberg.

GMRC Review: The Stochastic Man by Robert Silverberg

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog. This is Allie’s first GMRC review.

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. She has contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog. This is Allie’s first GMRC review.

The Stochastic Man by Robert Silverberg

The Stochastic Man by Robert Silverberg

Published: Harper & Row, 1975

Awards Nominated: Nebula, Campbell, Locus SF, Hugo

The Book:

“Lew Nichols is in the business of stochastic prediction. A mixture of sophisticated analysis and inspired guesswork, it is the nearest man can get to predicting the future. And Nichols is very good at it. So good that he is soon indispensable to Paul Quinn, the ambitious and charismatic mayor of New York whose sights are firmly set on the presidency.

There is nothing paranormal about stochastic prediction: Nichols can’t actually see the future. However, Martin Carvajal apparently can, and he offers to help Nichols do so, too. It’s an offer Nichols can’t resist, even though he can clearly see the devastating impact that knowing in advance every act of his life has on Carvajal. For Carvajal has even seen his own death.” ~WWend.com

At long last, here’s my first review for WWEnd’s Grand Master Reading Challenge, a challenge to read a novel by twelve different Grand Master authors during 2012. I picked up The Stochastic Man at a library discard sale, back when I was around ten years old. For some reason, 10-year-old me had a hard time getting into all the political and statistical talk, and it languished on my bookshelf unread for about two decades. This seemed like the perfect opportunity to finally get around to reading it.

My Thoughts:

In the beginning, The Stochastic Man was mostly about politics, and the use of predictive powers—either using stochastic methods or clairvoyance—to succeed in politics. As a result, there was a lot of discussion of campaigning tactics, often involving local New York City politics. I’m not a native New Yorker, so most of the references to major political figures in NYC’s history were little more than vaguely familiar names to me. Aside from the political discussions, the actual environment of NYC felt very lightly sketched, which made me feel even more distanced from the story. In broad terms, Silverberg’s ‘future’ NYC—which is set in the period of 1997-2000—was a dangerous place populated primarily by the sexually permissive, ‘bone smoking’ ultra-rich and violent, gang-dominated poor communities. I don’t think it was a particularly accurate vision of turn-of-the-century NYC, but I admit that I have only a tourist’s view of the city.

The Stochastic Man is not a particularly character-driven novel, and there is very little focus on characterization outside of the major charactrs, Lew Nichols and Martin Carvajal. I appreciated the ethnic diversity of the secondary characters, but, in the absence of significant characterization, they tended to be defined almost exclusively by their ethnicity and associated stereotypes. For instance, Lew’s wife Sundara, who grew up in California, was of Indian descent. The fact that she is Indian is explicitly referenced with respect to just about every character trait the reader is given for her—her beauty, her high libido, her mastery of the Kama Sutra, and even her supposed ‘natural affinity’ for religion, which led her to join a cult. The same goes for the Jewish financier Lombroso, whose elegant office contains a large display of historical Jewish artifacts. I’m not sure to what degree this kind of characterization might be annoying to other readers, but for me it was more of a minor irritation.

For me, the strongest part of The Stochastic Man, was its exploration of ideas relating to free will and determinism. The characters, world-building, and plot all seem to be essentially a structure within which to examine these central ideas. This theme becomes more prominent in later parts of the book, as Lew learns more about Carvajal’s clairvoyance and Sundara becomes involved with a cult known as Transit. His obsession with Carvajal’s supernatural certainty begins to take precedence over both his career as an expert at stochastic prediction and Paul Quinn’s developing presidential campaign. I liked how Silverberg used Transit and Carvajal’s clairvoyance to show two extreme views of the world, which are ultimately very similar.

For me, the strongest part of The Stochastic Man, was its exploration of ideas relating to free will and determinism. The characters, world-building, and plot all seem to be essentially a structure within which to examine these central ideas. This theme becomes more prominent in later parts of the book, as Lew learns more about Carvajal’s clairvoyance and Sundara becomes involved with a cult known as Transit. His obsession with Carvajal’s supernatural certainty begins to take precedence over both his career as an expert at stochastic prediction and Paul Quinn’s developing presidential campaign. I liked how Silverberg used Transit and Carvajal’s clairvoyance to show two extreme views of the world, which are ultimately very similar.

One the one hand, Carvajal represents absolute certainty, but that same certainty removes his own ability to control his life. He knows exactly how his life will play out, and he is powerless to change even the smallest aspect of it. As a result, he moves through his life like a puppet, slowly approaching his inevitable death. The Transit cult, on the other hand, glorifies randomness and uncertainty. Its followers attempt to set their ‘selves’ at a remove from the world, and let their lives become a series of causeless actions. Their future cannot be set in stone, because it has no pattern and no human intent. Though these two views are completely at odds, they both seem to feature the destruction of the decision-making self. Carvajal is living with a script from which he can never deviate, and the Transit followers discard their own agency in order to live without any kind of script. Therefore, neither side truly has free will—Carvajal lacks freedom, and Transit lacks will. Lew is attracted by Carvajal’s certainty, but he also wants to shape the future with his own hands. I think the story of Lew’s struggle to understand his own desires in relation to Carvajal’s power was ultimately more important, and more compelling, than the story of Paul Quinn’s political career.

My Rating: 3/5

The Stochastic Man was a story about a particular man’s political campaign, but I think its main intent was to address interesting ideas of concerning free will and determinism. I found the story to be much more interesting as it moved away from the day-to-day details of Paul Quinn’s political career and began to discuss the implications of the Transit belief system and Carvajal’s devastating supernatural clairvoyance. Aside from Lew and Carvajal, the characters weren’t particularly deeply developed, and most minor characters were primarily characterized by their ethnicity. Silverberg’s ‘future’ NYC may have little in common with actual turn-of-the-century NYC, but the location never felt much more than sketched out. I’m glad to have read The Stochastic Man, in the end, but I have a suspicion that this is not the best of Silverberg’s novels.

GMRC Review: A Time of Changes

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the second of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the second of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

In the mid-1960s we find many established genre writers starting to produce more mature and more literary fiction, culminating – amongst other brave and ground-breaking concerns – in significant stories criticizing militarism and the neo-imperialism agendas of the then US foreign policy, a trend that reached its peak with Grand Master Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War. This novel swooped most of the awards at the time and expressed just how successful the New Wave’s ideological platform had been. Arguably, the legacy of the New Wave remains inconclusive, considering the still on-going debates about the supposed “ghettoization” of the genre. Robert Silverberg is an exponent of the New Wave. Initially a prolific writer of “routine” SF in the 1950s, he began to produce some of the most interesting works in SF during this period, such as Thorns, The Masks of Time, Tower of Glass and A Time of Changes, which went on to win the Nebula Award in 1971. I have never read it before now.

In the mid-1960s we find many established genre writers starting to produce more mature and more literary fiction, culminating – amongst other brave and ground-breaking concerns – in significant stories criticizing militarism and the neo-imperialism agendas of the then US foreign policy, a trend that reached its peak with Grand Master Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War. This novel swooped most of the awards at the time and expressed just how successful the New Wave’s ideological platform had been. Arguably, the legacy of the New Wave remains inconclusive, considering the still on-going debates about the supposed “ghettoization” of the genre. Robert Silverberg is an exponent of the New Wave. Initially a prolific writer of “routine” SF in the 1950s, he began to produce some of the most interesting works in SF during this period, such as Thorns, The Masks of Time, Tower of Glass and A Time of Changes, which went on to win the Nebula Award in 1971. I have never read it before now.

A Time of Changes is clearly a literary experiment. And – sadly, dare I say – very much a product of its time. Don’t get me wrong – I did like the book, but even recognising the fact that it is a story from its decade, I feel it’s quite dated.

It is a simple story that deals plausibly with a variety of complex issues. The setting is that of a future society on the planet Borthan, earlier colonised by members of a religious sect. They followed a set of theological guidelines called the Covenant, which prohibited one from opening your heart and mind to others, essentially then, the denial of self. It is meant to prevent individuals from placing their personal burdens on others, to the extent that a ban is placed on the use of first-person pronouns. Referring to one self as “I” is a terrible breach of manners and has both dire social and legal consequences. The act of “self-bearing” is the ultimate sin, as our narrator informs us himself:

Obscene! Obscene! Already on the one sheet I have used the pronoun “I” close to twenty times, it seems. While also casually dropping such words as “my”, “me”, “myself”, more often that I dare to count. A torrent of shamelessness. I I I I I. If I exposed my manhood in the Stone Chapel of Manneran on Naming Day, I would be doing nothing so foul as I am doing here. (Orb edition 2009, page 17-18)

We see that not everyone on Borthan embraces the Covenant. The opening sentence “I am Kinnall Darival and I mean to tell you all about myself” introduces the reader to someone who eventually came to resist the Covenant. Kinnall continues to relate his experiences from early childhood onwards to this exact point where he can write his self-bearing sentence. We meet him as a prince in the province of Salla, the younger son of the prime septarch on Borthan. Tradition dictates that he has little chance of becoming septarch himself and therefore he decides to leave his home upon his father’s death. He wanders for years before making a home in the southern province. Here Kinnall meets an earthman who challenges his early assumptions about his society and convinces him to take a wonder drug that breaks down the barriers between human minds through a telepathic experience. This act changes Kinnall from a staunch bureaucrat into a prophet of self-bearing, with some tragic consequences, and ultimately leads to his self-imposed exile in the Burnt Lowlands.

I generally enjoy this type of narrative, and was often reminded of Severian’s odyssey in Gene Wolfe’s seminal The Book of the New Sun. Silverberg does a splendid job with the internal conflicts of someone who challenges the very fabric of their society and comes to question the basis of their world and its religion. Kinnall is a strong, often courageous, inquisitive character and, judging by this first-person narrative, very introspective. But, like Severian, he is also notably fallible, appalingly arrogant and destructively selfish – these traits finally lead to an unexpected tragedy near the end as he proceeds to spread the drug and the new way of thinking about his world. Silverberg handles Kinnall’s downfall with consummate skill. One can be forgiven for equating this downward spiral to the predictable calamity of established drug addiction. Perhaps, in some preternatural sense, Silverberg has crafted an ingenious rebuke against the unchecked drug use of this period.

I do have some problems with the book. The Orb edition (2009) that features an explanatory, contextual preface by Silverberg, also, thankfully, had a map. Without this map, the lengthy descriptions of the geography of Borthan and the imaginary names would have been totally lost on me. Despite the wonderfully crafted world-building in true Silverberg tradition, it had little relevance for me to the story. Well, maybe Kinnall’s exile in the Burnt Lowlands and its accompanied descriptions is perhaps an exception, as symbolic of his downfall, the ultimate destination of his personal odyssey. A big part of the book is therefore little more than world exploration and adds to the surface appearance of just an elementary story about just another drug. Yes, Silverberg’s writing is exceptional, intriguing and euphonious, but it ultimately doesn’t save the story from all the tedious musings and descriptions. At times it felt dull and lackadaisical – the story could have done with some trimming. It never really shifted past first gear.

In the preface Silverberg does acknowledge that since the publication of A Time of Changes he discovered other languages that avoided the construct “I”. It might have appeared a unique literary device at the time, but let’s not forget that Samuel R. Delany has attempted the same in Babel-17. The story would have been so much stronger if Silverberg avoided using the construct “one” all together; it is nothing else but a mere replacement of the pronoun “I”. Why bother? People were still referring to themselves directly. It would have been less artificial if he remained within the constructs of what we experience with Kinnall’s forlorn journey into Glin, where people actively avoid speaking about themselves at all, not even using the term “one”. And it is quite acceptable to refer to someone else as “you”, which felt equally contrived, for – unless I’m mistaken – “you” still implies a concept of “self”.

In the preface Silverberg does acknowledge that since the publication of A Time of Changes he discovered other languages that avoided the construct “I”. It might have appeared a unique literary device at the time, but let’s not forget that Samuel R. Delany has attempted the same in Babel-17. The story would have been so much stronger if Silverberg avoided using the construct “one” all together; it is nothing else but a mere replacement of the pronoun “I”. Why bother? People were still referring to themselves directly. It would have been less artificial if he remained within the constructs of what we experience with Kinnall’s forlorn journey into Glin, where people actively avoid speaking about themselves at all, not even using the term “one”. And it is quite acceptable to refer to someone else as “you”, which felt equally contrived, for – unless I’m mistaken – “you” still implies a concept of “self”.

It is a one-sided story, a telling from only Kinnall’s perspective. Don’t expect the opponents of self-bearing to be more than pitiable, brain-washed victims who will never know the true happiness that comes from sharing yourself with others. The story lacks a strong counter-protagonist and suffers greatly because of it.

In the final analysis, if you are looking for epic and multifarious adventures in Hard SF this book is not going to appeal to you. It is predominately a detailed character study with alluring exploration of an alien world and equally strange society that asks obstinate questions about the world around us. The first chapter and middle part of the book is engaging and exciting – pure Silverberg world-building, the remainder weaker, even disappointing. I find the book an important achievement in the history of SF, for its attempt to move away from technological explorations and pulpy space adventures into the challenging sub-genre of Soft SF, exploring difficult psychological and philosophical issues – and can appreciate why it won a Nebula Award, clearly an attempt to recognize the principles of the New Wave generation. I can’t say I agree with Silverberg’s conclusion, though. Self-repression does not need to be replaced by self-annihilation and the appearance that total intimacy is the best way through which to create a peaceful, happy society, is very naïve, typical of the idealism from that era. The idea of totally opening up to others with a certain reckless wantonness and allowing them into our minds in order to study our innermost thoughts, feelings and concerns is more than a little incommodious.

I’m glad to have read the book, but wanted to like it more. Silverberg has written much better novels, many of which did not go on to win an award.

Sources: Edward James, Science Fiction in the 20th Century. Opus (1994); Robert Silverberg, "Preface" in A Time Of Changes, Orb (2009)

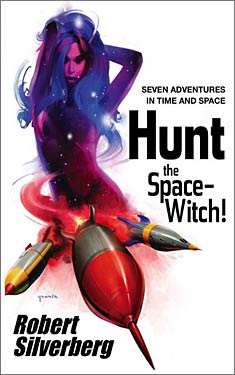

GMRC Review: Hunt the Space-Witch!

Editor’s Note: On his blog Stainless Steel Droppings blogger Carl V. Anderson reviews SF/F books and movies, conducts author interviews and even hosts his own reading challenge: The 2012 Science Fiction Experience. This is Carl’s second Grand Master review already, after The Stainless Steel Rat, and it’s a doozy!

Editor’s Note: On his blog Stainless Steel Droppings blogger Carl V. Anderson reviews SF/F books and movies, conducts author interviews and even hosts his own reading challenge: The 2012 Science Fiction Experience. This is Carl’s second Grand Master review already, after The Stainless Steel Rat, and it’s a doozy!

I first became aware of this collection of pulp-era short stories by author Robert Silverberg while perusing the internet last fall. The moment I saw Kieran Yanner’s dynamic retro cover I knew this book would have to be mine. I was reminded of the book when posting about my favorite SFF covers from books published in 2011 and promptly ordered a copy. Over the last two days I have immersed myself in the world of pulp-era science fiction and in so doing have discovered the talent that later propelled author Robert Silverberg to Grand Master status.

I first became aware of this collection of pulp-era short stories by author Robert Silverberg while perusing the internet last fall. The moment I saw Kieran Yanner’s dynamic retro cover I knew this book would have to be mine. I was reminded of the book when posting about my favorite SFF covers from books published in 2011 and promptly ordered a copy. Over the last two days I have immersed myself in the world of pulp-era science fiction and in so doing have discovered the talent that later propelled author Robert Silverberg to Grand Master status.

Pulp-era stories are all too often written off as something of inferior quality and in many ways in a best case scenario the term “pulp” has come to be synonymous with nothing more than guilty pleasure reading. I suspect that there is a great deal of merit in that. Common sense would dictate that in the heyday of pulp magazines publishers were cranking out magazines as fast as they could and authors were expected to follow a formula, write quickly, and be as prolific as possible if they wanted to make a living and keep their work in the public eye. And to be certain there is probably much in the days of pulp science fiction that wasn’t worth reading then and does not merit attention now. By the same token, there are common themes, archetypes, and story structures in pulp adventure stories that resonate with today’s audience. In my childhood it was creators like George Lucas who reached back into the pulp era for inspiration when crafting what would become the pop cultural phenomenon Star Wars. And though some may be loathe to admit it, there is a universality to these tales that are the ancestors of popular stories today.

The stories are often sensational, featuring rugged heroes prone to decisive action, conflict between defined “good guys” and “bad guys”, action over characterization or science, romantic melodrama over reason. These are space yarns, at times little different than their mystery or western counterparts. The setting may be on another planet or on Earth in the far-flung future but the stories themselves are as recognizable to fans of fiction in general as they are to fans of the genre of science fiction.

Planet Stories Books has reprinted 7 of Robert Silverberg’s stories originally published in the short-lived digest Science Fiction Adventures, edited by John Carnell. In the introduction Silverberg sets the stage for what I believe is the proper attitude with which to approach these stories–he relates the story of his first encounter with Planet Stories Magazine and how he found it to be a “treasurehouse of wonders”. He then went on to collect and devour all of the back issues of the magazine. Silverberg relates the circumstances around the creation of these seven stories and where they were originally published and at no time in his introduction does he approach this work with a self-deprecating or apologetic tone. Silverberg remembers the “heady rapture” of the pulp stories of his youth and recalls how both he and Carnell approached Science Fiction Adventures as a way to honor the love they had for Planet Stories.

Please allow me a moment to give a brief synopsis of each novella with my non-spoiler thoughts included.

Slaves of the Star Giants

Lloyd Harkins awakens in a place where quiet, melancholy giants lumber with unknown purpose and 15 foot tall robots crash pell-mell through the woods. Placed unceremoniously in a tribe of barbarians, Harkins soon finds himself at odds with the tribes’ leader and banished back to the savage forest. As events unfold, Harkins begins to suspect that he is merely a pawn in a game much larger than himself and the anger that ignites will lead him to either victory, or to death.

The future-Earth described by Silverberg called to mind other stories that I’ve read, like Jack Vance’s Tales of the Dying Earth and Larry Niven’s A World Out of Time. Technology is akin to black magic to the people who no longer know how to use it or what purpose it had. Some of the nostalgic charm that these older stories often possess was present in this first story mostly in the form of an enormous computer that required tape to be fed into the machine in order to make it function.

Spawn of the Deadly Sea

Earth lies entirely underwater, the result of a long-ago invasion by a mysterious alien race. Humanity exists in two-spheres: the floating cities that are the refuge of the progeny of those that survived the invasion and the vast oceans which are home to the Seaborn, hybrid man-made creatures that were mankind’s last hope to defeat the alien invaders. But alas they were too little, too late. In this far future the world is divided into nine sections of the sea, each ruled over by the Sea-lords, brigands who enact tribute to protect the shipments of goods from one floating city to another. Young Dovirr is tired of city life and longs for the glory he imagines is part of the life of a Thalassarch, ruler of the Sea-lords. With the bravado of untried youth Dovirr gambles and wins a spot on the Garyun, determined to make his dreams of naval conquest a reality. He soon discovers there is more to the sea than the occasional battle with would-be pirates and humanity’s pent up anger over the past alien invasion is just about to find a release.

This story is very much a rousing swash-buckling pirate adventure, yet within those confines it nevertheless touches on some very interesting concepts, like prejudice and mindless obedience. The concept of entire Earth cities being covered and remaining covered with water stirred my imagination and I couldn’t stop the flow of cinematic images of what it would look like to dive these remains.

The Flame and the Hammer

The Emperor of the Galactic Empire is growing old and feeble and grumbles of rebellion from a few wayward planets are beginning to reach his ear. Ras Duyair lives on one of these planets, Aldrynne, the capital planet of a seven planet system. His father, High Priest of the Temple of the Suns has often spoken of the mythological Hammer of Aldrynne, a weapon prophesied to bring down the fall of the Empire. When his father is killed under Imperial interrogation as to the whereabouts of this weapon it soon becomes apparent that the knowledge of what this weapon was or where it can be found has died with him. Ras Duyair flees to a neighboring planet to escape those who believe his father has passed this information down to him and he soon becomes embroiled in a rebellion against the Galactic Empire.

With shades of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, particularly in the use of an ancient Rome inspired system of government, Silverberg has crafted his version of the tale of a young hero born into obscurity who will rise up to take on an Empire.

Valley Beyond Time

Sam Thornhill lives alone in a peaceful valley, a place of utter tranquility. Or at least he thought he was alone until the arrival of a beautiful woman and a squat man shatter his peace. Soon there are nine people in the valley, six humans and three aliens. As the bliss of Thornhill’s illusions begin to fade he discovers that this majestic valley may not be all that it seems and forces beyond his imagination might never allow any of them to leave.

This is the kind of story you would expect to have been later adapted for an episode of The Twilight Zone. And in some manner it has, for this is a story that has been told many times and in many ways in short story format and also in television shows like the aforementioned Twilight Zone and the various iterations of Star Trek. Despite its familiarity, the themes of freedom and control are as compelling as ever and Silverberg builds the suspense in a satisfyingly deliberate manner.

Hunt the Space-Witch!

When the starship on which Barsac serves lands on the planet Glaurus, he begs leave of his captain to set out to track down an old friend of his to fill a vacant position on the ship. In the years of his absence, Glaurus has become considerably more dangerous and Barsac soon discovers that his friend has gone missing, a possible recruit of the enigmatic Cult of the Space-Witch. As people begin to die around him Barsac becomes more determined to rescue his friend at any cost, even if the cost is his own life.

What sounds as if it would be an incredibly hokey bad-religious-cult story demonstrates that not all pulp stories are created equal and that “space adventures” can sometimes be as dark and sinister and deadly as the cold reaches of space itself.

The Silent Invaders

Major Abner Harris of the Interstellar Development Corps is on his way to Earth for a long overdue vacation. Except that it really isn’t overdue nor is it a vacation. For Major Harris is not really Major Harris, nor is he the Terran male that he appears to be. Harris is really a member of the race of the planet Darruui, a reluctant recruit chosen to infiltrate Earth for reasons that will be revealed as the story unfolds. Harris soon finds he is not alone in his deception and that members of Darruui’s sworn enemy, the Medlin, are also on Earth in the guise of native-born Terrans. In a story worthy of the espionage/counter-espionage of noir detective stories, The Silent Invaders foretells the next stage of the evolution of humanity and examines the lengths people, and aliens, will go to in order to make sure that their self-interests are protected.

This is an interesting addition to the collection because it bucks the tradition of the rest of the stories printed here, and presumably the majority of pulp sf stories, in that it introduces a strong and capable female character into the mix and allows her to be just that. In the introduction Silverberg mentions that he has expanded this story into a novel and I can safely say it is one novel I will be keeping an eye out for.

Spacerogue

Barr Herndon has a grudge, the kind of deep-seated grudge born out of seeing his family murdered and their lands destroyed at the whim of a self-indulgent ruler. Now he is back and it soon becomes apparent that he is looking for revenge and he will stop at nothing, including an almost fanatical devotion to his own gray moral code, to get it.

This is a story of nobles and serfs, a feudal society in a far distant galaxy. More than any other tale in this collection, Spacerogue shocked me. Right from the beginning something happens that I did not see coming and the surprises continue as Herndon gets closer to his desired vengeance.

Hunt the Space-Witch! is not high literature. Deep characterization and exhaustive examination of ideas were not the order of the day. These seven novellas were written with magazine space considerations in mind and were written to capture the imagination and to hopefully infuse a sense of wonder in the reader. They were meant to thrill and to excite. Today they are works of pure nostalgia but at the same time they demonstrate that even at an early age Silverberg was talented and imaginative. The stories may follow a predictable pattern but do not always have predictable endings and I was pleasantly surprised with how often I was shocked with a particular story element or direction a story was taking. Characters made decisions I did not anticipate and there was a degree of ambiguity about some of the protagonists that made it hard to like them even when you were on their side. At the same time there is a comfort that comes with the certain knowledge that the short stories in a collection will all have a definite beginning, middle and end and will not be reliant on something esoteric or ambiguous to lend them credibility or to elicit praise.

It is akin to damning with faint praise to say that a story, or in this case a collection of novellas, is “fun”. However, it is not my intention to denigrate Silverberg’s pulp science fiction tales when I say that they are just that–pure, unadulterated FUN. I picked this collection up late yesterday evening and found myself reading well into the night. I awoke early this morning and immediately started where I left off, finishing it later this afternoon while sitting out on my back porch in warm, un-January-like weather. My disappointment when there were no more stories left to read is a compliment to how much I was entertained by Silverberg’s wonder-filled nostalgic science fiction.

Before I leave off I have to give praise to Planet Stories for their book design. I have already mentioned my affection for the cover art, but what makes the book’s presentation special is the nod to the pulp magazines that inspired Silverberg to write these stories in the first place. From the magazine-style Table of Contents to the ad-filled back pages featuring full-page book art and a retro-style subscription page, this book is an homage to a time when science fiction publishing was so very different than what it is today. I should point out that on the publishing data page it erroneously reports that these stories were previously published separately in Planet Stories magazine. This does not concur with Silverberg’s introduction in which he talks about the untimely (for him) demise of Planet Stories magazine saying, “I never did get a chance to have some grand and gaudy space adventure published in that grand and gaudy magazine”. As mentioned above these stories were published in Science Fiction Adventures magazine. A minor quibble about an otherwise snappy trade paperback.

Before I leave off I have to give praise to Planet Stories for their book design. I have already mentioned my affection for the cover art, but what makes the book’s presentation special is the nod to the pulp magazines that inspired Silverberg to write these stories in the first place. From the magazine-style Table of Contents to the ad-filled back pages featuring full-page book art and a retro-style subscription page, this book is an homage to a time when science fiction publishing was so very different than what it is today. I should point out that on the publishing data page it erroneously reports that these stories were previously published separately in Planet Stories magazine. This does not concur with Silverberg’s introduction in which he talks about the untimely (for him) demise of Planet Stories magazine saying, “I never did get a chance to have some grand and gaudy space adventure published in that grand and gaudy magazine”. As mentioned above these stories were published in Science Fiction Adventures magazine. A minor quibble about an otherwise snappy trade paperback.

And so I leave you with this. Silverberg’s stories are indeed “grand and gaudy”, filled with tropes and trappings that by this era are well worn and sometimes eyed with scorn. But Robert Silverberg is a skilled writer and evidence of that skill is present in these early stories. Where others wrote unrestrained and sometimes incredibly wacky over-the-top pulp, Silverberg concentrated on telling a good story with evidence that he was putting his heart into being a success. Hunt the Space-Witch! is a fun-filled collection of space adventures that open a window to a fascinating period of science fiction history.

Nerds Make Better Lovers

In case you weren’t convinced by the sexual conquests of the Tri-Lams in Revenge of the Nerds, io9 has uncovered more proof that it’s hip to be square. In an article mostly about careers that sci-fi authors used to hold, out comes some 1960s porn by Robert Silverberg. That was, of course, before he snagged his first noms for both the Hugo and Nebula awards for Thorns, in 1968.

Campbell winner, PKD and double-Nebula nominee, Barry N. Maltzberg was apparently dipping his pen in the illicit well, according to the article.

That got us to wondering, how many more pornographic authors might be in the WWEnd database? I suppose that depends on whether you count Stranger in a Strange Land as porn.

Full Details

Full Details