Forays into Fantasy: Edgar Rice Burroughs One-Hundred Years On

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

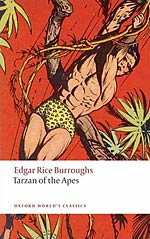

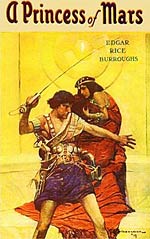

Around age eleven, Edgar Rice Burroughs was my favorite writer, and I devoured all of his books I could find. Rereading Burroughs’ first two novels today–A Princess of Mars (originally serialized in 1912 as "Under the Moons of Mars") and Tarzan of the Apes (serialized later in 1912), both of which have just been reprinted in beautiful facsimile editions by the Library of America–it’s harder to overlook the weaknesses, but the appeal remains clear. The prose is often awkward, incredible plot coincidences abound, relationships are simplistic, race and gender assumptions are problematic (more on that below), yet all these problems are (mostly) redeemed in the best of Burroughs’s novels by the relentless storytelling imagination and energy at work. Over one-hundred million copies sold, and counting…

Around age eleven, Edgar Rice Burroughs was my favorite writer, and I devoured all of his books I could find. Rereading Burroughs’ first two novels today–A Princess of Mars (originally serialized in 1912 as "Under the Moons of Mars") and Tarzan of the Apes (serialized later in 1912), both of which have just been reprinted in beautiful facsimile editions by the Library of America–it’s harder to overlook the weaknesses, but the appeal remains clear. The prose is often awkward, incredible plot coincidences abound, relationships are simplistic, race and gender assumptions are problematic (more on that below), yet all these problems are (mostly) redeemed in the best of Burroughs’s novels by the relentless storytelling imagination and energy at work. Over one-hundred million copies sold, and counting…

Burroughs was the most popular fantastic writer of the first third of the twentieth century, and it was during this period that the fantastic became “ghettoized” as it moved into the realm of the pulps, while mainstream writers for the most part stopped delving into the fantastic. As Paul Kincaid writes in “American Fantasy 1820–1950” (in The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature):

“By the 1920s and 1930s the freedom that had allowed Jack London [and, earlier, Mark Twain or Henry James, among others] to move readily between realism and the fantastic was becoming more restricted. A mode now most readily identified with the smutty comedies of [Thorne] Smith and [James Branch] Cabell or, more damningly, with the grotesque horrors of Lovecraft and the crude, highly coloured adventures of [Robert E.] Howard could not be employed for serious literary purposes.”

As reading for pleasure became more widespread due in part to the development of low-cost “dime novels” and pulp magazines, the literary divide widened. The three main branches of the pulp fantastic were exemplified and inspired by Burroughs’ “science fantasy” adventures, Howard’s sword and sorcery (Conan, etc.), and Lovecraft’s weird fiction. Writers with serious literary ambitions no longer wanted to be associated with a mode of writing increasingly linked to the pulps.

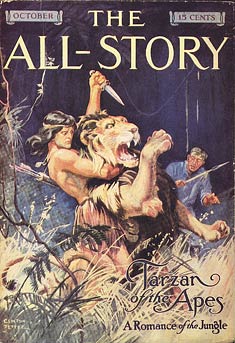

Burroughs got started earlier than Lovecraft or Howard and, reading him today, I think of him as the ultimate pulp writer–embodying both the positive and negative aspects of those early magazines, as well as informing all who would follow in his footsteps. Burroughs famously turned to writing relatively late, his military ambitions during the 1890s having been quashed. He failed to get into West Point or to be chosen as one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, but did spend some time in the cavalry in Arizona before being discharged for health reasons–an experience that helped inform the opening chapters of Princess–before attempting and abandoning a series of business ventures during the 1900s. He tried writing in part out of desperation, needing to support his young family, after reaching the conclusion that he could write better stories than the majority he was reading in the pulps of the time. (He was right!) His two best-known novels, both of which would spawn long-running series, both appeared in The All-Story magazine in 1912, the year Burroughs turned thirty-seven.

Burroughs got started earlier than Lovecraft or Howard and, reading him today, I think of him as the ultimate pulp writer–embodying both the positive and negative aspects of those early magazines, as well as informing all who would follow in his footsteps. Burroughs famously turned to writing relatively late, his military ambitions during the 1890s having been quashed. He failed to get into West Point or to be chosen as one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, but did spend some time in the cavalry in Arizona before being discharged for health reasons–an experience that helped inform the opening chapters of Princess–before attempting and abandoning a series of business ventures during the 1900s. He tried writing in part out of desperation, needing to support his young family, after reaching the conclusion that he could write better stories than the majority he was reading in the pulps of the time. (He was right!) His two best-known novels, both of which would spawn long-running series, both appeared in The All-Story magazine in 1912, the year Burroughs turned thirty-seven.

By his death in 1950, Burroughs had, in the prolific pulp tradition, published nearly seventy novels, and several more appeared posthumously. Along with the Barsoom (Mars) series, which eventually included eleven books, and the Tarzan series (twenty-four books), the trilogy beginning with The Land That Time Forgot probably remains best-known today. In addition, he wrote the Carson of Venus series, the Pellucidar hollow-Earth series beginning with At the Earth’s Core (which included a Tarzan crossover) and numerous other genre stories, as well as a few attempts at Westerns and contemporary fiction. To my mind, Burroughs peaked in the 1920s, with novels like Tarzan the Untamed (1920) and The Chessmen of Mars (1922), and both series are worth pursuing for readers who enjoy the opening books. After the ‘20s, however, diminishing returns set in, as will be clear to anyone who attempts to get through the last few volumes of the two series, or compares the tired-seeming Venus novels (1934–1946) to the earlier Mars books. Even as an enthusiastic adolescent, I think I gave up after sixteen or eighteen Tarzan novels.

Tarzan, of course, would live on in films, television, and comics, most of which greatly annoyed fans of the books, since they tended to leave out the more fantastic aspects (ancient lost cities, underground civilizations, dinosaurs, immortality drugs), but most importantly because they deemphasized the most interesting aspect of Tarzan’s character–his dual existence as a primordial jungle denizen and a highly intellectual English aristocrat. The combination makes him a superman. (And certainly, one of the impacts of the popularity of Tarzan and other pulp heroes would be on the creation of superhero comics beginning in the late ‘30s.)

Tarzan, of course, would live on in films, television, and comics, most of which greatly annoyed fans of the books, since they tended to leave out the more fantastic aspects (ancient lost cities, underground civilizations, dinosaurs, immortality drugs), but most importantly because they deemphasized the most interesting aspect of Tarzan’s character–his dual existence as a primordial jungle denizen and a highly intellectual English aristocrat. The combination makes him a superman. (And certainly, one of the impacts of the popularity of Tarzan and other pulp heroes would be on the creation of superhero comics beginning in the late ‘30s.)

Tarzan is really Lord Greystoke, whose parents were stranded on the African coast following a mutiny by the crew of the ship they were traveling on. Lady Alice died soon after, leaving a despairing father with no way to feed the infant. When a band of great apes–an invented species that seems to be the “missing link” between apes and humanity, with the rudiments of a spoken language–breaks into the cabin and kills Lord Greystoke, a female ape who had just lost her own baby adopts the boy and forces the rest of the band to tolerate Tarzan (“white skin” in the ape language) and allow her to raise him as one of them.

Despite having no direct contact with people, Tarzan does gain access to his parents’ cabin. Sitting with their skeletons, he discovers books, including, crucially, an illustrated dictionary, and his hereditary intelligence kicks in as he, amazingly, teaches himself to read. Once he started to identify groups of letters with accompanying pictures, “his progress was rapid… and the active intelligence of a healthy mind endowed by inheritance with more than ordinary reasoning powers” took over. For Burroughs, the aristocratic white man is clearly the peak of evolution, and even being brought up by apes cannot prevent the “higher” qualities from asserting themselves. Later, meeting Jane Porter brings his hereditary nature to the fore: “It was the hall-mark of his aristocratic birth, the natural outcropping of many generations of fine breeding, and hereditary instinct of graciousness which a lifetime of uncouth and savage training could not eradicate.” The impact of heredity and environment, and the conflicting appeals of his own kind and jungle life, will remain central to Tarzan’s character.

In A Princess of Mars, John Carter is similarly presented as a superior white aristocrat (an American southerner, in his case), who becomes the greatest man on Mars, just as Tarzan surpasses the rest of humanity due to his superior intelligence and character. Carter’s “features were regular and clear cut, his hair black and closely cropped, while his eyes were of a steel grey, reflecting a strong and loyal character, filled with fire and initiative. His manners were perfect, and his courtliness was that of a typical southern gentleman of the highest type.” Even his family’s slaves “fairly worshipped the ground he trod”! All in all, Carter is a “splendid specimen of manhood,” irresistible to the aristocratic Barsoomian princess Dejah Thoris: “Was there ever such a man! she exclaimed. ‘I know that Barsoom has never before seen your like… Alone, a stranger, hunted, threatened, persecuted, you have done in a few short months what in all the past ages of Barsoom no man has ever done.” As for Tarzan, Jane “noted the graceful majesty of his carriage, the perfect symmetry of his magnificent figure and the poise of his well shaped head upon his broad shoulders. What a perfect creature! There could be naught of cruelty or baseness beneath that godlike exterior. Never, she thought, had such a man strode the earth since God created the first in his own image.”

In A Princess of Mars, John Carter is similarly presented as a superior white aristocrat (an American southerner, in his case), who becomes the greatest man on Mars, just as Tarzan surpasses the rest of humanity due to his superior intelligence and character. Carter’s “features were regular and clear cut, his hair black and closely cropped, while his eyes were of a steel grey, reflecting a strong and loyal character, filled with fire and initiative. His manners were perfect, and his courtliness was that of a typical southern gentleman of the highest type.” Even his family’s slaves “fairly worshipped the ground he trod”! All in all, Carter is a “splendid specimen of manhood,” irresistible to the aristocratic Barsoomian princess Dejah Thoris: “Was there ever such a man! she exclaimed. ‘I know that Barsoom has never before seen your like… Alone, a stranger, hunted, threatened, persecuted, you have done in a few short months what in all the past ages of Barsoom no man has ever done.” As for Tarzan, Jane “noted the graceful majesty of his carriage, the perfect symmetry of his magnificent figure and the poise of his well shaped head upon his broad shoulders. What a perfect creature! There could be naught of cruelty or baseness beneath that godlike exterior. Never, she thought, had such a man strode the earth since God created the first in his own image.”

The racial implications are uncomfortable to the modern reader, but they are not as simplistically racist as they might at first appear. Both characters are the only white men in their respective worlds, and this is seen as a source of their superiority. Yet both are more at home in their adopted worlds than with their own kind. The racism is accompanied by the idea that the “lower” races (apes, blacks, Tharks, etc.) have positive qualities that have been lost by modern “civilized” whites. Carter is more at home with the green Tharks and red Martians, just as Tarzan feels the pull of jungle life whenever he returns to the constraints of civilization. And, despite the implication of miscegenation, Carter marries red-skinned Dejah Thoris, and the couple’s son will hatch from an egg. (Exactly how this works is happily never explained, and this is the sort of thing that, to me, makes Burroughs a fantasy rather than a science fiction writer.)

Carter is the embodiment of the Western hero suited for a frontier life–a life no longer available to him at home, but possible on Barsoom, which can be seen as an extension of the “manly” frontier life Burroughs himself had longed for in his military years. And Tarzan’s superiority to other men is not just because he is a white aristocrat in black Africa, but also because his upbringing by the apes has freed him from the constraints of civilization. Thus, it is the combination of heredity and upbringing that makes him superior to both Africans and whites. After learning the ways of civilization, which Tarzan/Greystoke takes to quite easily, he never loses the call of the wild.

Carter is the embodiment of the Western hero suited for a frontier life–a life no longer available to him at home, but possible on Barsoom, which can be seen as an extension of the “manly” frontier life Burroughs himself had longed for in his military years. And Tarzan’s superiority to other men is not just because he is a white aristocrat in black Africa, but also because his upbringing by the apes has freed him from the constraints of civilization. Thus, it is the combination of heredity and upbringing that makes him superior to both Africans and whites. After learning the ways of civilization, which Tarzan/Greystoke takes to quite easily, he never loses the call of the wild.

“Tarzan had no sooner entered the jungle than he took to the trees and it was with a feeling of exultant freedom that he swung once more through the forest branches. This was life! Ah, how he loved it! Civilization held nothing like this in its narrow and circumscribed sphere, hemmed in by restrictions and conventionalities. Even clothes were a hindrance and a nuisance. At last he was free. He had not realized what a prisoner he had been.”

Throughout the series, Greystoke would be drawn back to civilization by his family and hereditary obligations, but he would always long for and ultimately return to the jungle–his true home. Similarly, at the end of A Princess of Mars, when Carter returns to Earth as mysteriously as he had originally appeared on Mars, all he can think of is his desire to return to the dying red planet. “I can see her shining in the sky through the little window by my desk, and tonight she seems calling to me again.” He, too, will return for the sequel.

Tarzan became one of the best known character creations of the twentieth century, but it is Barsoom that would have the biggest impact on fantasy and science fiction. Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, with its dying planet crisscrossed with canals and home to ancient ruins of once-great civilizations, can be traced back to Burroughs, as can the entire subgenre of science fantasy and planetary romance, as traced through the works of Leigh Brackett (Sea-Kings of Mars), Jack Vance (Big Planet), Michael Moorcock (the Michael Kane trilogy), Gene Wolfe (The Book of the New Sun), George Lucas (Star Wars), and countless others. In a planetary romance, the alien planet and its exploration are important aspects of the story; the means of getting there are not. In Princess, Carter, longing to reach Mars, “stretched out my arms toward the god of my vocation and felt myself drawn with the suddenness of thought through the trackless immensity of space.” Such stories are often marketed as science fiction, but they are distinguished from fantasy only in that the imaginary settings are on other planets rather than undefined earthly realms like Middle Earth or Westeros.

Burroughs’s influence, then, arises from the subgenre he pioneered–exciting adventure stories set in fantastic locales with one foot in reality, and he is seen as the progenitor of science fantasy and the planetary romance. But is he still worth reading? The books have not avoided becoming dated (Tarzan more so than Barsoom), but Burroughs is a natural storyteller, and it’s easy to see why these books were so compelling to legions of readers over the years, especially younger readers like my ten-year-old self, for which Burroughs has served as a major gateway into fantasy and science fiction. It could be argued that genre readers no longer need to bother with Burroughs, but if so, this is because his influence has been so thoroughly absorbed into the field, even those who haven’t read the originals have still, in a sense, internalized them by reading so many works influenced by them. Apparently, one of the criticisms of the recent John Carter film was that, for many viewers, it seemed overly familiar and unoriginal. This is the potential fate of the most influential stories–decades of homage and imitation can make the original seem unoriginal!

Burroughs’s influence, then, arises from the subgenre he pioneered–exciting adventure stories set in fantastic locales with one foot in reality, and he is seen as the progenitor of science fantasy and the planetary romance. But is he still worth reading? The books have not avoided becoming dated (Tarzan more so than Barsoom), but Burroughs is a natural storyteller, and it’s easy to see why these books were so compelling to legions of readers over the years, especially younger readers like my ten-year-old self, for which Burroughs has served as a major gateway into fantasy and science fiction. It could be argued that genre readers no longer need to bother with Burroughs, but if so, this is because his influence has been so thoroughly absorbed into the field, even those who haven’t read the originals have still, in a sense, internalized them by reading so many works influenced by them. Apparently, one of the criticisms of the recent John Carter film was that, for many viewers, it seemed overly familiar and unoriginal. This is the potential fate of the most influential stories–decades of homage and imitation can make the original seem unoriginal!

Next up: The Enchanter stories of L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt…

Full Details

Full Details

5 Comments

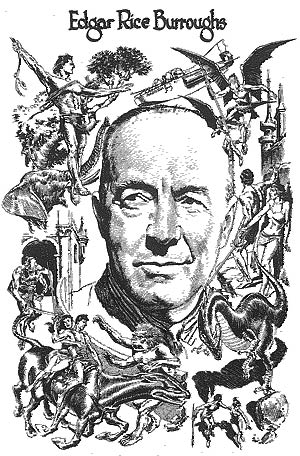

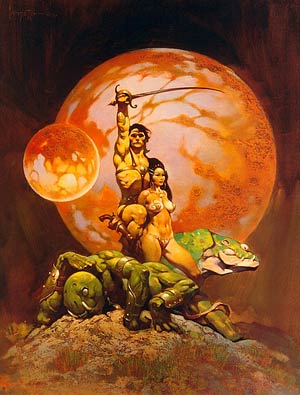

Scott, thanks for another great post. It’s been a loooong time since I’ve read any Burroughs, but I still vividly remember my first encounter with him. It was my father’s copy of Tarzan the Terrible (1921), read when I had at most only the vaguest notion of who Tarzan might be, and it was an incredibly immersive and satisfying experience. You’re right that Burroughs tapered off after the ’20s, but at least he had his shining moments in the sun. Thanks also for highlighting the great art. The art from those LoA covers is stunning, as is the Frazetta. Where did the art of Burroughs surrounded by his creations come from?

Engelbrecht: I found that illustration on the front page of the official ERB website. It’s by Al Williamson and Reed Crandall (best known for their work on EC Comics in the ’50s), but I don’t know when the illustration was done (or for what). The Frazetta piece was on the cover of the Science Fiction Book Club edition of The Princess of Mars from 1970; it was one of the "4 books for a dollar" I got when I joined as a kid! I wish I could better articulate why these books are so immersive and satisfying, as you note, despite the weak writing. I guess it’s the power of pure storytelling…

@Scott I think you are spot on! These are wonderful, imaginative stories and as such have a lasting appeal. Thanks for another excellent piece and the effort you make in crafting it.

Thanks for another interesting addition to your series! I’m enjoying learning more about older fantastic fiction through your posts :). I think you’re right that Tarzan and John Carter have been absorbed into the field. I’ve never actually read any Burroughs, but I’m still familiar with the premise and general story of each series. I feel as though I should read at least a few of his novels at some point (maybe from the 1920s, as you mentioned!), because they are so well-known and influential.

Thanks, Emil & Allie. I’ve been enjoying writing them… @Allie: I’ve heard it argued that Princess of Mars is no longer a necessary book for understanding the field, due to its influence being transmitted through so many other works that are more palatable to a modern reader. (I think the idea is that we end up absorbing it without actually reading it.) Whether it is only of "historical interest" or is still a good read will probably depend on your tolerance for the writing style…

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.