Forays into Fantasy: Edgar Rice Burroughs One-Hundred Years On

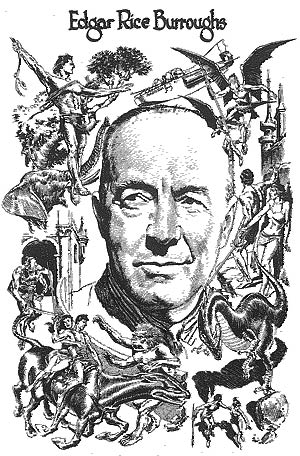

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Around age eleven, Edgar Rice Burroughs was my favorite writer, and I devoured all of his books I could find. Rereading Burroughs’ first two novels today–A Princess of Mars (originally serialized in 1912 as "Under the Moons of Mars") and Tarzan of the Apes (serialized later in 1912), both of which have just been reprinted in beautiful facsimile editions by the Library of America–it’s harder to overlook the weaknesses, but the appeal remains clear. The prose is often awkward, incredible plot coincidences abound, relationships are simplistic, race and gender assumptions are problematic (more on that below), yet all these problems are (mostly) redeemed in the best of Burroughs’s novels by the relentless storytelling imagination and energy at work. Over one-hundred million copies sold, and counting…

Around age eleven, Edgar Rice Burroughs was my favorite writer, and I devoured all of his books I could find. Rereading Burroughs’ first two novels today–A Princess of Mars (originally serialized in 1912 as "Under the Moons of Mars") and Tarzan of the Apes (serialized later in 1912), both of which have just been reprinted in beautiful facsimile editions by the Library of America–it’s harder to overlook the weaknesses, but the appeal remains clear. The prose is often awkward, incredible plot coincidences abound, relationships are simplistic, race and gender assumptions are problematic (more on that below), yet all these problems are (mostly) redeemed in the best of Burroughs’s novels by the relentless storytelling imagination and energy at work. Over one-hundred million copies sold, and counting…

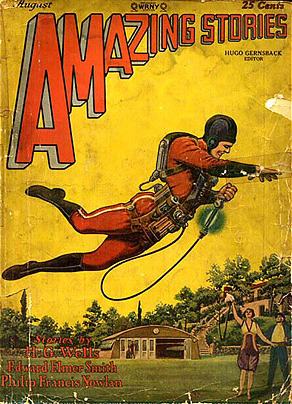

Burroughs was the most popular fantastic writer of the first third of the twentieth century, and it was during this period that the fantastic became “ghettoized” as it moved into the realm of the pulps, while mainstream writers for the most part stopped delving into the fantastic. As Paul Kincaid writes in “American Fantasy 1820–1950” (in The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature):

“By the 1920s and 1930s the freedom that had allowed Jack London [and, earlier, Mark Twain or Henry James, among others] to move readily between realism and the fantastic was becoming more restricted. A mode now most readily identified with the smutty comedies of [Thorne] Smith and [James Branch] Cabell or, more damningly, with the grotesque horrors of Lovecraft and the crude, highly coloured adventures of [Robert E.] Howard could not be employed for serious literary purposes.”

As reading for pleasure became more widespread due in part to the development of low-cost “dime novels” and pulp magazines, the literary divide widened. The three main branches of the pulp fantastic were exemplified and inspired by Burroughs’ “science fantasy” adventures, Howard’s sword and sorcery (Conan, etc.), and Lovecraft’s weird fiction. Writers with serious literary ambitions no longer wanted to be associated with a mode of writing increasingly linked to the pulps.

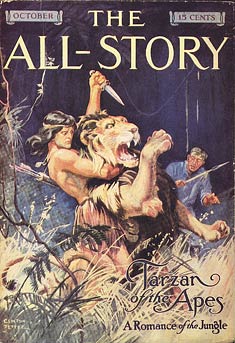

Burroughs got started earlier than Lovecraft or Howard and, reading him today, I think of him as the ultimate pulp writer–embodying both the positive and negative aspects of those early magazines, as well as informing all who would follow in his footsteps. Burroughs famously turned to writing relatively late, his military ambitions during the 1890s having been quashed. He failed to get into West Point or to be chosen as one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, but did spend some time in the cavalry in Arizona before being discharged for health reasons–an experience that helped inform the opening chapters of Princess–before attempting and abandoning a series of business ventures during the 1900s. He tried writing in part out of desperation, needing to support his young family, after reaching the conclusion that he could write better stories than the majority he was reading in the pulps of the time. (He was right!) His two best-known novels, both of which would spawn long-running series, both appeared in The All-Story magazine in 1912, the year Burroughs turned thirty-seven.

Burroughs got started earlier than Lovecraft or Howard and, reading him today, I think of him as the ultimate pulp writer–embodying both the positive and negative aspects of those early magazines, as well as informing all who would follow in his footsteps. Burroughs famously turned to writing relatively late, his military ambitions during the 1890s having been quashed. He failed to get into West Point or to be chosen as one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, but did spend some time in the cavalry in Arizona before being discharged for health reasons–an experience that helped inform the opening chapters of Princess–before attempting and abandoning a series of business ventures during the 1900s. He tried writing in part out of desperation, needing to support his young family, after reaching the conclusion that he could write better stories than the majority he was reading in the pulps of the time. (He was right!) His two best-known novels, both of which would spawn long-running series, both appeared in The All-Story magazine in 1912, the year Burroughs turned thirty-seven.

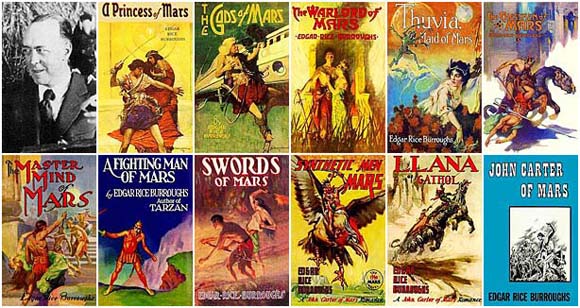

By his death in 1950, Burroughs had, in the prolific pulp tradition, published nearly seventy novels, and several more appeared posthumously. Along with the Barsoom (Mars) series, which eventually included eleven books, and the Tarzan series (twenty-four books), the trilogy beginning with The Land That Time Forgot probably remains best-known today. In addition, he wrote the Carson of Venus series, the Pellucidar hollow-Earth series beginning with At the Earth’s Core (which included a Tarzan crossover) and numerous other genre stories, as well as a few attempts at Westerns and contemporary fiction. To my mind, Burroughs peaked in the 1920s, with novels like Tarzan the Untamed (1920) and The Chessmen of Mars (1922), and both series are worth pursuing for readers who enjoy the opening books. After the ‘20s, however, diminishing returns set in, as will be clear to anyone who attempts to get through the last few volumes of the two series, or compares the tired-seeming Venus novels (1934–1946) to the earlier Mars books. Even as an enthusiastic adolescent, I think I gave up after sixteen or eighteen Tarzan novels.

Tarzan, of course, would live on in films, television, and comics, most of which greatly annoyed fans of the books, since they tended to leave out the more fantastic aspects (ancient lost cities, underground civilizations, dinosaurs, immortality drugs), but most importantly because they deemphasized the most interesting aspect of Tarzan’s character–his dual existence as a primordial jungle denizen and a highly intellectual English aristocrat. The combination makes him a superman. (And certainly, one of the impacts of the popularity of Tarzan and other pulp heroes would be on the creation of superhero comics beginning in the late ‘30s.)

Tarzan, of course, would live on in films, television, and comics, most of which greatly annoyed fans of the books, since they tended to leave out the more fantastic aspects (ancient lost cities, underground civilizations, dinosaurs, immortality drugs), but most importantly because they deemphasized the most interesting aspect of Tarzan’s character–his dual existence as a primordial jungle denizen and a highly intellectual English aristocrat. The combination makes him a superman. (And certainly, one of the impacts of the popularity of Tarzan and other pulp heroes would be on the creation of superhero comics beginning in the late ‘30s.)

Tarzan is really Lord Greystoke, whose parents were stranded on the African coast following a mutiny by the crew of the ship they were traveling on. Lady Alice died soon after, leaving a despairing father with no way to feed the infant. When a band of great apes–an invented species that seems to be the “missing link” between apes and humanity, with the rudiments of a spoken language–breaks into the cabin and kills Lord Greystoke, a female ape who had just lost her own baby adopts the boy and forces the rest of the band to tolerate Tarzan (“white skin” in the ape language) and allow her to raise him as one of them.

Despite having no direct contact with people, Tarzan does gain access to his parents’ cabin. Sitting with their skeletons, he discovers books, including, crucially, an illustrated dictionary, and his hereditary intelligence kicks in as he, amazingly, teaches himself to read. Once he started to identify groups of letters with accompanying pictures, “his progress was rapid… and the active intelligence of a healthy mind endowed by inheritance with more than ordinary reasoning powers” took over. For Burroughs, the aristocratic white man is clearly the peak of evolution, and even being brought up by apes cannot prevent the “higher” qualities from asserting themselves. Later, meeting Jane Porter brings his hereditary nature to the fore: “It was the hall-mark of his aristocratic birth, the natural outcropping of many generations of fine breeding, and hereditary instinct of graciousness which a lifetime of uncouth and savage training could not eradicate.” The impact of heredity and environment, and the conflicting appeals of his own kind and jungle life, will remain central to Tarzan’s character.

In A Princess of Mars, John Carter is similarly presented as a superior white aristocrat (an American southerner, in his case), who becomes the greatest man on Mars, just as Tarzan surpasses the rest of humanity due to his superior intelligence and character. Carter’s “features were regular and clear cut, his hair black and closely cropped, while his eyes were of a steel grey, reflecting a strong and loyal character, filled with fire and initiative. His manners were perfect, and his courtliness was that of a typical southern gentleman of the highest type.” Even his family’s slaves “fairly worshipped the ground he trod”! All in all, Carter is a “splendid specimen of manhood,” irresistible to the aristocratic Barsoomian princess Dejah Thoris: “Was there ever such a man! she exclaimed. ‘I know that Barsoom has never before seen your like… Alone, a stranger, hunted, threatened, persecuted, you have done in a few short months what in all the past ages of Barsoom no man has ever done.” As for Tarzan, Jane “noted the graceful majesty of his carriage, the perfect symmetry of his magnificent figure and the poise of his well shaped head upon his broad shoulders. What a perfect creature! There could be naught of cruelty or baseness beneath that godlike exterior. Never, she thought, had such a man strode the earth since God created the first in his own image.”

In A Princess of Mars, John Carter is similarly presented as a superior white aristocrat (an American southerner, in his case), who becomes the greatest man on Mars, just as Tarzan surpasses the rest of humanity due to his superior intelligence and character. Carter’s “features were regular and clear cut, his hair black and closely cropped, while his eyes were of a steel grey, reflecting a strong and loyal character, filled with fire and initiative. His manners were perfect, and his courtliness was that of a typical southern gentleman of the highest type.” Even his family’s slaves “fairly worshipped the ground he trod”! All in all, Carter is a “splendid specimen of manhood,” irresistible to the aristocratic Barsoomian princess Dejah Thoris: “Was there ever such a man! she exclaimed. ‘I know that Barsoom has never before seen your like… Alone, a stranger, hunted, threatened, persecuted, you have done in a few short months what in all the past ages of Barsoom no man has ever done.” As for Tarzan, Jane “noted the graceful majesty of his carriage, the perfect symmetry of his magnificent figure and the poise of his well shaped head upon his broad shoulders. What a perfect creature! There could be naught of cruelty or baseness beneath that godlike exterior. Never, she thought, had such a man strode the earth since God created the first in his own image.”

The racial implications are uncomfortable to the modern reader, but they are not as simplistically racist as they might at first appear. Both characters are the only white men in their respective worlds, and this is seen as a source of their superiority. Yet both are more at home in their adopted worlds than with their own kind. The racism is accompanied by the idea that the “lower” races (apes, blacks, Tharks, etc.) have positive qualities that have been lost by modern “civilized” whites. Carter is more at home with the green Tharks and red Martians, just as Tarzan feels the pull of jungle life whenever he returns to the constraints of civilization. And, despite the implication of miscegenation, Carter marries red-skinned Dejah Thoris, and the couple’s son will hatch from an egg. (Exactly how this works is happily never explained, and this is the sort of thing that, to me, makes Burroughs a fantasy rather than a science fiction writer.)

Carter is the embodiment of the Western hero suited for a frontier life–a life no longer available to him at home, but possible on Barsoom, which can be seen as an extension of the “manly” frontier life Burroughs himself had longed for in his military years. And Tarzan’s superiority to other men is not just because he is a white aristocrat in black Africa, but also because his upbringing by the apes has freed him from the constraints of civilization. Thus, it is the combination of heredity and upbringing that makes him superior to both Africans and whites. After learning the ways of civilization, which Tarzan/Greystoke takes to quite easily, he never loses the call of the wild.

Carter is the embodiment of the Western hero suited for a frontier life–a life no longer available to him at home, but possible on Barsoom, which can be seen as an extension of the “manly” frontier life Burroughs himself had longed for in his military years. And Tarzan’s superiority to other men is not just because he is a white aristocrat in black Africa, but also because his upbringing by the apes has freed him from the constraints of civilization. Thus, it is the combination of heredity and upbringing that makes him superior to both Africans and whites. After learning the ways of civilization, which Tarzan/Greystoke takes to quite easily, he never loses the call of the wild.

“Tarzan had no sooner entered the jungle than he took to the trees and it was with a feeling of exultant freedom that he swung once more through the forest branches. This was life! Ah, how he loved it! Civilization held nothing like this in its narrow and circumscribed sphere, hemmed in by restrictions and conventionalities. Even clothes were a hindrance and a nuisance. At last he was free. He had not realized what a prisoner he had been.”

Throughout the series, Greystoke would be drawn back to civilization by his family and hereditary obligations, but he would always long for and ultimately return to the jungle–his true home. Similarly, at the end of A Princess of Mars, when Carter returns to Earth as mysteriously as he had originally appeared on Mars, all he can think of is his desire to return to the dying red planet. “I can see her shining in the sky through the little window by my desk, and tonight she seems calling to me again.” He, too, will return for the sequel.

Tarzan became one of the best known character creations of the twentieth century, but it is Barsoom that would have the biggest impact on fantasy and science fiction. Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, with its dying planet crisscrossed with canals and home to ancient ruins of once-great civilizations, can be traced back to Burroughs, as can the entire subgenre of science fantasy and planetary romance, as traced through the works of Leigh Brackett (Sea-Kings of Mars), Jack Vance (Big Planet), Michael Moorcock (the Michael Kane trilogy), Gene Wolfe (The Book of the New Sun), George Lucas (Star Wars), and countless others. In a planetary romance, the alien planet and its exploration are important aspects of the story; the means of getting there are not. In Princess, Carter, longing to reach Mars, “stretched out my arms toward the god of my vocation and felt myself drawn with the suddenness of thought through the trackless immensity of space.” Such stories are often marketed as science fiction, but they are distinguished from fantasy only in that the imaginary settings are on other planets rather than undefined earthly realms like Middle Earth or Westeros.

Burroughs’s influence, then, arises from the subgenre he pioneered–exciting adventure stories set in fantastic locales with one foot in reality, and he is seen as the progenitor of science fantasy and the planetary romance. But is he still worth reading? The books have not avoided becoming dated (Tarzan more so than Barsoom), but Burroughs is a natural storyteller, and it’s easy to see why these books were so compelling to legions of readers over the years, especially younger readers like my ten-year-old self, for which Burroughs has served as a major gateway into fantasy and science fiction. It could be argued that genre readers no longer need to bother with Burroughs, but if so, this is because his influence has been so thoroughly absorbed into the field, even those who haven’t read the originals have still, in a sense, internalized them by reading so many works influenced by them. Apparently, one of the criticisms of the recent John Carter film was that, for many viewers, it seemed overly familiar and unoriginal. This is the potential fate of the most influential stories–decades of homage and imitation can make the original seem unoriginal!

Burroughs’s influence, then, arises from the subgenre he pioneered–exciting adventure stories set in fantastic locales with one foot in reality, and he is seen as the progenitor of science fantasy and the planetary romance. But is he still worth reading? The books have not avoided becoming dated (Tarzan more so than Barsoom), but Burroughs is a natural storyteller, and it’s easy to see why these books were so compelling to legions of readers over the years, especially younger readers like my ten-year-old self, for which Burroughs has served as a major gateway into fantasy and science fiction. It could be argued that genre readers no longer need to bother with Burroughs, but if so, this is because his influence has been so thoroughly absorbed into the field, even those who haven’t read the originals have still, in a sense, internalized them by reading so many works influenced by them. Apparently, one of the criticisms of the recent John Carter film was that, for many viewers, it seemed overly familiar and unoriginal. This is the potential fate of the most influential stories–decades of homage and imitation can make the original seem unoriginal!

Next up: The Enchanter stories of L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt…

10 Minutes of John Carter

So this is supposed to be the first 10 minutes of the movie. It feels more like a montage of scenes than 10 contiguous minutes to me but I like it pretty well. The production values are really good at least but it’s just a bit disjointed for my tastes. It’s like they’re trying to squeeze in too much back story into too little screen time so they can get on to Mars quicker. Guess I can’t blame them for that. I hope it evens out after the cave. Can’t wait for Saturday!

John Carter Sneak Peek

So far I’ve liked the John Carter trailers but the news surrounding this movie does not seem to be very positive. It has dampened my enthusiasm quite a bit. This extended scene trailer has brought me hope again. I desperately want this movie to be good. What do you think? Am I asking too much?

New John Carter Trailer!

Now this looks epic! Much more information than in the first trailer and a ton of decent looking special effects including a good look at Woola. He’s a little too cute but not bad for Disney. The Tharks feature heavily in this trailer and they look alternatingly good and bad throughout. What I’d like to see is more of the white ape. He’s freakin’ huge!

Overall I like the new trailer though I’m a little concerned about the special effects. I’m sure this is not the final version and knowing they have until March to put on whatever finishing touches are left makes me feel a bit more optimistic.

What do you think of the new trailer? How about Woola?

John Carter (of Mars) Trailer!

I’m a huge fan of the Barsoom Series by Edgar Rice Burroughs and when I heard they were making a movie, a serious non-SyFy movie, mind you, I still had the same reaction I always have when one of my favorite books gets the movie treatment: "Great, I hope they don’t f*** it up."

I’ve gone from so much hope in the idea to so much bitter disappointment in the execution in previous movie adaptations that I’ve become more than a little jaded to these things. It’s a self defense mechanism. If they screw it all to hell then I’m prepared for the letdown and I don’t have so far to fall. If somehow the stars align and they get it right then I’m pleasantly surprised. Not a bad way to exit the theater.

After seeing this trailer for John Carter I’m feeling pretty damn optimistic that the stars are favorable for Disney. John looks bad-ass but not overly muscled. I like Boris Vallejo’s John as much as the next guy but this John just looks right. Dejah Thoris looks appropriately gorgeous and capable – like someone worth fighting for. And as for Tars Tarkas, mighty Jeddak of Thark? Freakin’ amazing! This is the best rendition of a Thark that I’ve ever seen. The look of the film is spot on for me. Oh, and nobody is running around stark naked. I’m down with that… except maybe for Dejah Thoris.

What do you guys think? Am I setting myself up for a fall?

In Praise of Pulp

I have a confession to make. I. Love. Pulp. Pulp science fiction, that is.

I have a confession to make. I. Love. Pulp. Pulp science fiction, that is.

Ever since I was a kid I’ve been enamored of Pulp SF. I love the cheesy, and often-times racy, over-the-top Buck Rogers covers: the muscular man of action chasing down the fiendish alien abductor who’s trying to make off with the dame. And what a dame! Scantily-clad buxom lasses all – with incongruous fish bowl helmets that somehow hold back the vacuum of space but never muss their flowing locks. And rockets! Always with the rockets! Rocket shaped space ships poised for takeoff from some exotic alien planet with multiple moons and a few rings thrown in for good measure. That’s how you know its sci-fi, my friends.

But the goodness is not just on the front cover. Turn a pulp over and you get the glory of the blurb. The blurb never fails to amuse and entice with a combination of ridiculous hyperbole and hopelessly anachronistic phrasing. You know you’re reading a pulp blurb when you find yourself doing the Batman TV show voiceover as you read the synopsis. Go ahead; try reading the blurb for The Skylark of Space by E.E. “Doc” Smith below. You almost have to go all Batman on it.

“Scientist Richard Seaton had discovered the secret of the complete release of ultimate energy. And his discovery gave him the key to the exploration of the Universe in all its cosmic immensity. But Seaton’s arch-rival, the powerful, unscrupulous Duquesne, was determined to gain control of this awesome secret too…

The climax came in deep space, when Seaton, Duquesne and three others – two of them women – were marooned, countless light-years from Earth, with only one chance in a million of ever returning…”

Ultimate energy AND cosmic immensity? Two of them women for crying out loud! What’s not to love?

But wait, there’s more!

Pulp books are a feast for the senses! Of course, I’m talkin’ ‘bout proper books here. You know. With pages. Not sterile digital versions on your iSomething™ or Kindle. Great as those devises are, and I love them too so don’t start hating; they just don’t do a pulp justice. I love the dry texture of the brittle binding and chipped corners and the scritch-scratch sound of stiff yellowed pages turning. There is no yellow like the yellow of old pulp pages. You won’t find that in your Crayola box. Then there’s the pleasantly musty smell of old paper and ink. The noble rot. You can smell it now, can’t you? Ah yes. So much for eInk. And the dust. What’s a pulp without years of accumulated bookstore dust? Your Nook won’t make you sneeze like that.

But, of course, all of that is secondary to the real joy of a pulp: the story. Oh, the stories you’ll read.

The best pulps are short and fast reads with minimal exposition and break-neck pacing. Get in and get out. Hang on as best you can. They are rollicking adventures with no pretense to anything other than a good time. You see, there is very little depth to a pulp. No political undercurrent or social commentary. No complex structure or moral ambiguity. It’s all on the shiny space-age polymer surface. They are gloriously and unabashedly formulaic from beginning to end.

In a good pulp you’ll find enough SF tropes to make Margaret Atwood roll her eyes. These stories established the stereotypes after all. The pulp future has it all. Flying cars, ray guns, robots and time machines. Space stations, silver jump suits and artificial gravity. Galactic empires, floating cities and epic battles. Exotic aliens, beautiful women and strapping heroes. And even “talking squids in outer space.”

What about the characters? They are exactly as awesome as they are predictable and cliché.

The good guys are good guys ‘cause how else would they be? They epitomize honor and chivalry and self reliance. You want to be the good guy because he’s a badass. He gets the girl on the cover and always metes out justice to the villains along the way. True men of action like John Carter of Mars:

“I am a citizen of two worlds; Captain John Carter of Virginia, Prince of the House of Tardos Mors, Jeddak of Helium. Take this man to your goddess, as I have said, and tell her, too, that as I have done to Xodar and Thurid, so also can I do to the mightiest of her Dators. With naked hands, with long-sword or with short-sword, I challenge the flower of her fighting-men to combat.”

You don’t pull the mask off the old Lone Ranger and you don’t mess around with John….

The good women embody old time virtues of the fairer sex: beauty, grace and love with a healthy dose of can-do attitude while always remaining more or less helpless and pliant as the plot dictates. You’ll have to forgive them that. It was a different time and besides, a hero needs someone to save.

The bad guys are bad because they can’t compete with the good guys any other way. Many of the best bad guys are aliens. They’ve been poking around in our collective anus for decades – of course they’re the baddies!

“Hideous egotist,” said O-Tar, “prepare to die and assume not to dictate to O-Tar the jeddak. He has passed sentence and all three of you shall feel the jeddak’s naked steel. I have spoken!”

You just know the bad guy is gonna die after a pronouncement like that.

The bad gals are spurned lovers or victims turned cruel. They’re angry and opportunistic and sexy as all get out. They have to tempt the good guys you know. No gray areas in these characters. You’re never supposed to empathize with the bad seeds. That would just slow things down. Your job is to recognize that they’re bad and revel in their comeuppance when it eventually arrives.

Both heroes and villains alike avail themselves of the most outlandish “science” and technology imaginable. This is where the gloves come off. Pulp revels in elaborate scientific explanations that are both silly and wonderful in the extreme. There are pages of this stuff in the Skylark Series:

“The zone of force is necessary to shield certain items of equipment from ether vibrations; as any such vibration inside the controlling fields of force renders observation or control of the higher orders of rays impossible.”

Um, yeah. May the fields of force be with you.

Of course, sometimes the author can’t be bothered with too much jargon and opts to explain it all away as the product of advanced alien intelligence beyond our ken. I’ll buy that. Action is the name of the game in pulp and the second option leaves more room for space battles so we still come out winners in the end. There is no time to waste on physics or relativity. This is all pre-wormhole or subspace stuff here so it’s all about speed! The Kessel Run in four parsecs? A walk in the park. These guys fly to the other side of the galaxy at “titanic speeds”, save the day and make it back in time for a cold one.

Yes, yes, you’re right. There are certainly better books to be reading. Books that read like a steak dinner with a nice Chianti followed by an indie film. They leave you wondering about life the universe and everything. Maybe even touch your life or say something to you. I love those books too.

But every so often, I like to travel “back to the future” – to the beginnings of the genre for a ripping yarn told with earnest joy. Pulp SF books are popcorn and candy, domestic beer and an old B-movie with friends. They leave you breathless and bemused and wanting more. They make you smile and feel nostalgic. They take you away from things serious and mundane for a little while and they don’t demand too much. What more could you ask?

If you’ve never read pulp SF, give it a try. You don’t know what you’re missing. I have spoken.

Some great pulp series to consider:

- Barsoom Series by Edgar Rice Burroughs

- Before the Golden Age edited by Isaac Asimov

- Lucky Starr Series by Isaac Asimov

- Skylark Series by E.E. “Doc” Smith

- Lensman Series by E.E. “Doc” Smith

- The Conan Chronicles, Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle by Robert E. Howard

- The Conan Chronicles, Volume 2: The Hour of the Dragon by Robert E. Howard

Barsoom!

The Barsoom Series by Edgar Rice Burroughs is one of the most famed science fiction series ever written and we’ve just added it to the Worlds Without End database.

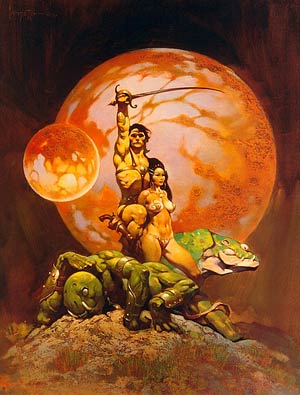

Barsoom has been around for many years and there are dozens of different printings available online and at your local independent bookstore. The covers shown here are the first edition hardcovers which are highly collectible and can be very expensive. More recent editions can be had for cheap and in a myriad of different cover styles including some illustrated by the late great Frank Frazetta.

The first five books in the series are out of copyright in the US and are freely available online via Project Gutenberg, johncarterofmars.ca and many other eBook outlets. Books six through ten are public domain in Australia and are available from Project Gutenberg Australia. You can also read the entire series online for free from Barsoomian.net. The final book, John Carter of Mars, is an omnibus of two shorter works, John Carter and the Giants of Mars (1941) and John Carter and The Skeleton Men of Jupiter (1943), so they can be read online for free but only as separate works. Neat little side step, that.

You can also do like I’m doing and get your Barsoom via email or RSS feed from DailyLit.com.They’ll send you the entire A Princess of Mars, one chapter at a time on your own schedule, so you can start your week off with a little classic SF waiting in your inbox. It’s the modern equivalent of the serialized original publication. That just feels right for some reason. Happy reading.

Full Details

Full Details