Time to Vote! New Locus “All-Centuries Poll” Now Online

With Americans soon going to the polls in a close and pivotal election, another poll with long-lasting ramifications is taking place. Locus Magazine has launched a new “All-Centuries Poll” of the best science fiction and fantasy from 1900-2010!

With Americans soon going to the polls in a close and pivotal election, another poll with long-lasting ramifications is taking place. Locus Magazine has launched a new “All-Centuries Poll” of the best science fiction and fantasy from 1900-2010!

Of the lists featured on Worlds Without End based on fan popularity, I see the Locus All-Time Best Poll as being the most authoritative and interesting, since the voters in the Locus poll tend toward the industry professionals, writers, and serious fans that read the magazine. The most recent all-time poll was taken in 1998, and was restricted to books published through 1990. Leaving more recent books out of such a poll helps keep the focus on those that have stood the test of time. The number one novel in the 1998 poll (as well as in a couple of previous all-time polls) was Frank Herbert’s Dune, followed by The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, The Left Hand of Darkness, The Foundation Trilogy, and Stranger in a Strange Land.

The question now is where these novels will fall in the poll now being conducted at Locus Online, fourteen years later. The ballot is now available. Unlike the annual “best of the year” polls conducted by Locus, in which the votes of Locus subscribers are weighted more strongly than non-subscribers, this will be a popular poll with no weightings. Anyone can participate, and WWEnd members have a rare opportunity to add their opinions to the creation of one of the lists featured on the site.

There are ten categories in the poll: five each covering the best of the twentieth century and the best of the twenty-first century (2001-2010). For each of the two periods, poll participants can list their top ten in five categories: science fiction novel, fantasy novel, science fiction/fantasy novella, science fiction/fantasy novelette, and science fiction/fantasy short story. For those wanting to participate in all categories, then, up to one-hundred pieces of fiction can be listed! In order to make the process a little less daunting, Locus has made available long lists of award-winning, critically-acclaimed, and popular 20th century novels, 20th century short fiction, 21st century novels, and 21st century short fiction. Poll participants can use these lists (or not) to jog memories and help put together their top tens in the various categories, but participants are welcome to vote for works that are not on these lists.

Along with other list-lovers, I’ll be fascinated to see how this turns out. There is always a danger with popular internet polls that there will be organized attempts at “ballot-box stuffing,” though this seems much less likely to affect the twentieth century poll than the twenty-first century poll. It will be interesting to see whether Dune and the other favorites of past generations of fans remain as popular, and which more recent books appear for the first time or move up the list. Let the speculation begin! (Listen to the October 27 Coode Street podcast for some thoughts on possible outcomes by Jonathan Strahan and Gary K. Wolfe.) It will take some work, but I’m glad to have an excuse to make all those top-ten lists, and will post them in the forum at some point. I’d also be glad to see what other WWEnders list as their favorites, and hope you’ll make your voices heard in the poll! (And if you’re in the U.S., don’t forget to go to the polls!)

GMRC Review: Mission of Gravity by Hal Clement

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Hal Clement‘s Mission of Gravity (1954) is a love letter to science. Serialized in Astounding in 1953, it’s often pointed to as a prototypical “hard” science fiction novel of the ‘50s, with the story driven more by the solution of scientific problems and the achievement of scientific discovery than by character or plot. Clement, a science teacher, specialized in this sort of science fiction, which may be why he seems to be one of the more neglected of the Grand Masters from the perspective of modern SF fans. But Clement’s third novel is a cut above much of the hard SF of the time, which has a tendency to become dated as science advances, because of the way Clement melds the scientific explanations with the characters’ motivations, which in turn drive the plot and create suspense and interest in the story.

Another way Clement infuses his narrative with science is by making the exploration of the setting a major source of interest for the reader, as well as the source of the obstacles that must be overcome in order for the plot to advance and the characters to achieve their goals. The protagonists’ quest involves overcoming the environmental difficulties created by the setting itself. That setting is the planet Mesklin, a disc-shaped world with an intense gravity field. The gravity ranges from three times that of Earth’s along the equator (the “rim”) to seven-hundred times at the poles. Intelligent life, capable of living under the extreme gravity, has developed there. The Mesklinites are hydogen-breathing, chitin-shelled, caterpillar-like creatures fifteen inches long and two inches in diameter, with “dozens of suckerlike feet,” and pincers functioning as hands. The point-of-view of the novel is that of Barlennan, a merchant trader and leader of a Mesklinite crew that sails the methane oceans of the storm-tossed planet in search of profit.

Forays into Fantasy (and Horror): Bram Stoker’s Dracula and the Origin of the Vampire

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

In Greek mythology, the Lamia was a Libyan queen who was transformed into an unclean child-eating demon. The story later became part of European folklore—a story told to frighten misbehaving children. In many versions, the Lamia became a serpentine monster who seductively lured men to their doom, in order to drink their blood. According to Brian Stableford in The Encylopedia of Fantasy, this legend, combined with “Eastern European superstitions regarding cannibalistically inclined reanimated corpses,” were the roots of the literary vampire, although the latter type of story seemed to be more closely related to the modern zombie.

In Greek mythology, the Lamia was a Libyan queen who was transformed into an unclean child-eating demon. The story later became part of European folklore—a story told to frighten misbehaving children. In many versions, the Lamia became a serpentine monster who seductively lured men to their doom, in order to drink their blood. According to Brian Stableford in The Encylopedia of Fantasy, this legend, combined with “Eastern European superstitions regarding cannibalistically inclined reanimated corpses,” were the roots of the literary vampire, although the latter type of story seemed to be more closely related to the modern zombie.

In 1819, John Polidori, formerly Lord Byron’s physician, took a fragmentary story of Byron’s and expanded it into The Vampyre: A Tale, whose vampire protagonist, Lord Ruthven, was seen from the time of the book’s publication to be a thinly disguised portrayal of Byron himself—a character that became the initial template for the modern vampire in horror fiction. Ruthven was “the satanic, world-weary aristocrat whose eyes have a hypnotic effect, especially upon women, and in whom vampirism and seduction are a part of the same process. The languor of the Byronic vampire is a pose, [however,] for his energy is infernal” (John Clute, also from The Encylopedia). See the blog post on Frankenstein’s Forefathers for more on the story of the intertwined origins of the two best-known monsters in horror fiction, involving Byron, Polidori, and Mary Shelley, during the summer of 1816.

Forays into Fantasy: Robert E. Howard’s Conan

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Honestly, I didn’t think Robert E. Howard’s series of Conan stories, written and mostly published during the first half of the 1930s, would be of much interest to me. But given their importance as the tales that mark the beginning of a major subgenre that is still going strong today—what would come to be known as sword and sorcery—I thought my fantasy history tour would be incomplete without at least giving them a look. Given the continued popularity and influence of these stories, I should have known that there would be more to them than my preconceptions of a giant barbarian warrior with an equally giant sword hacking his way from one adventure to the next (not that there isn’t some truth to that description), and it turns out there are good reasons that Howard’s stories are considered central to the development of fantasy, and that the best of them are still interesting and enjoyable today.

Honestly, I didn’t think Robert E. Howard’s series of Conan stories, written and mostly published during the first half of the 1930s, would be of much interest to me. But given their importance as the tales that mark the beginning of a major subgenre that is still going strong today—what would come to be known as sword and sorcery—I thought my fantasy history tour would be incomplete without at least giving them a look. Given the continued popularity and influence of these stories, I should have known that there would be more to them than my preconceptions of a giant barbarian warrior with an equally giant sword hacking his way from one adventure to the next (not that there isn’t some truth to that description), and it turns out there are good reasons that Howard’s stories are considered central to the development of fantasy, and that the best of them are still interesting and enjoyable today.

One reason I hadn’t approached them before was my memory of the endless rows of Conan paperbacks on bookstore shelves while haunting the science fiction and fantasy sections during the 1970s, along with the multiple similar series, spinoffs, and even parodies. By that time, sword and sorcery had been stereotyped as the realm of muscular barbarians, scantily-clad damsels in distress, and escapist adventure, and the sheer repetitiveness of the cover images seemed to verify it. As it turns out, this reaction was unfair to Howard’s creation, which went through a long and confusing publishing history that in some ways took the character further and further from its origin in Howard’s stories.

GMRC Review: Ring Around the Sun by Clifford D. Simak

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Clifford D. Simak’s stories embody contradictions. Like Ray Bradbury, his writing looks back longingly to an idyllic rural Midwestern childhood. As John Clute and David Pringle put it in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Simak “reigned as the finest pastoral elegist of his genre” from the Golden Age through the 1980s. Unlike Bradbury, though, Simak stuck with science fiction, rather than drifting into realism, and his books have always struck me as a strange combination of futuristic SF ideas and a criticism of the technological, social and economic trends that make the manifestation of those ideas possible. The main theme of Ring Around the Sun (1953), one of his most acclaimed novels, and the one that may come closest to crystallizing the themes that run throughout his career, is that humanity’s biological and social evolution hasn’t kept up with its technological capabilities, resulting in the inevitability that humanity will destroy itself.

Clifford D. Simak’s stories embody contradictions. Like Ray Bradbury, his writing looks back longingly to an idyllic rural Midwestern childhood. As John Clute and David Pringle put it in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Simak “reigned as the finest pastoral elegist of his genre” from the Golden Age through the 1980s. Unlike Bradbury, though, Simak stuck with science fiction, rather than drifting into realism, and his books have always struck me as a strange combination of futuristic SF ideas and a criticism of the technological, social and economic trends that make the manifestation of those ideas possible. The main theme of Ring Around the Sun (1953), one of his most acclaimed novels, and the one that may come closest to crystallizing the themes that run throughout his career, is that humanity’s biological and social evolution hasn’t kept up with its technological capabilities, resulting in the inevitability that humanity will destroy itself.

In 1987, Earth is still threatened by Cold War superpower rivalries, with war seemingly always around the corner, while the ennui of modern life has led people to retreat into a movement called Pretentionism. Clubs have formed in which people get together to share their hobby of historical role-playing, retreating into an imagined past that implies a psychological rejection of the contemporary world. Jay Vickers is an introverted writer who disdains the Pretentionists, but realizes that his own retreat from the world into writing is just another symptom of the same social malaise.

Where to Find DRM-Free eBooks, and Why It’s Worth the Effort

A couple of weeks back, Rico penned a post saying goodbye to eBook DRM (digital rights management), following Tor Books’ announcement that it had extended its new no-DRM policy worldwide. The common sense arguments against DRM are laid out in that post, but, despite Tor’s decision, the brave new world of DRM-free eBooks isn’t quite here yet. Many authors and smaller publishers are embracing DRM-free books, but the big publishers and the major eBook retailers are still resistant.

A couple of weeks back, Rico penned a post saying goodbye to eBook DRM (digital rights management), following Tor Books’ announcement that it had extended its new no-DRM policy worldwide. The common sense arguments against DRM are laid out in that post, but, despite Tor’s decision, the brave new world of DRM-free eBooks isn’t quite here yet. Many authors and smaller publishers are embracing DRM-free books, but the big publishers and the major eBook retailers are still resistant.

This is not surprising, since an important profit-making strategy for large corporations is to restrict competition, and that is exactly what DRM does. It’s well known by this point that DRM does not prevent digital piracy—the argument usually made for it. What it does is prevent book buyers from moving their files across reading platforms. From a publisher perspective, this could increase profits by increasing the chance that some readers will end up re-buying books in the future, if they ever want to switch to a different reader, or somehow lose access to the account their books are attached to. It makes even more sense from the perspective of Amazon and Barnes and Noble, the major book retailers and producers of the two top e-readers. If you’ve already bought a hundred eBooks from Amazon, and you can’t read them on a Nook or a Sony Reader, you will feel locked into continuing to use the Kindle, even if a competing e-reader comes along that you’d like to switch to. And if you stick with the Kindle, you won’t be buying books from Barnes and Noble or any other DRM-restricted e-bookstore.

There are advantages to staying with a particular eBook “ecosystem.” Amazon makes a great e-reader, can sell you just about any eBook that’s available, and is very easy to use. Barnes and Noble can make similar claims. But whichever you choose, you’re pretty much stuck with that company (or whoever buys it out in the future) forever. And, for the moment, the big publishers are determined to “double down” on DRM, as Cory Doctorow describes here. Hatchette Book Group is trying to force its authors to sign contracts requiring them to make sure that any books they publish, even when published through other publishers, contain DRM. An author who has published with Hatchette and Tor, according to Doctorow, has received a letter pressuring the author to ensure that Tor does not remove the DRM from the author’s Tor books. It seems clear that these companies are not going to give up easily.

There are advantages to staying with a particular eBook “ecosystem.” Amazon makes a great e-reader, can sell you just about any eBook that’s available, and is very easy to use. Barnes and Noble can make similar claims. But whichever you choose, you’re pretty much stuck with that company (or whoever buys it out in the future) forever. And, for the moment, the big publishers are determined to “double down” on DRM, as Cory Doctorow describes here. Hatchette Book Group is trying to force its authors to sign contracts requiring them to make sure that any books they publish, even when published through other publishers, contain DRM. An author who has published with Hatchette and Tor, according to Doctorow, has received a letter pressuring the author to ensure that Tor does not remove the DRM from the author’s Tor books. It seems clear that these companies are not going to give up easily.

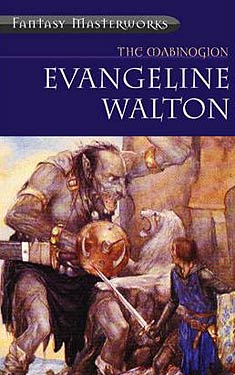

Forays into Fantasy: The Mabinogion Tetralogy by Evangeline Walton

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

The paperback republication of The Lord of the Rings in the 1960s and its subsequent wild success created a whole new audience for fantasy, and led to a fantasy publishing boom in the 1970s. Along with spawning, for better or worse, an unending stream of new epic fantasy, the belated popularity of J. R. R. Tolkien also sent publishers looking for other older fantasy novels to reprint. One result was Ballantine’s Adult Fantasy series, which reprinted sixty-five novels between 1969 and 1974, under the editorship of Lin Carter. Books by Lord Dunsany, Clark Ashton Smith, H. P. Lovecraft, William Hope Hodgson, James Branch Cabell, and many others now considered fantasy classics were brought back into print and released as affordable paperbacks for fantasy-hungry readers. One of Carter’s more obscure finds was the eighteenth book in the series, The Island of the Mighty by Evangeline Walton, a novelistic retelling of the fourth “branch” of the Mabinogion—a series of Welsh-language legends of the British Isles dating from the fourteenth century, the stories themselves most likely originating in the twelfth. Though it had received some critical acclaim on release in 1936 under its original unfortunate (though not inaccurate) title The Virgin and the Swine, it had failed to sell and was pretty well forgotten by the time Carter brought it to Ballantine’s attention.

The paperback republication of The Lord of the Rings in the 1960s and its subsequent wild success created a whole new audience for fantasy, and led to a fantasy publishing boom in the 1970s. Along with spawning, for better or worse, an unending stream of new epic fantasy, the belated popularity of J. R. R. Tolkien also sent publishers looking for other older fantasy novels to reprint. One result was Ballantine’s Adult Fantasy series, which reprinted sixty-five novels between 1969 and 1974, under the editorship of Lin Carter. Books by Lord Dunsany, Clark Ashton Smith, H. P. Lovecraft, William Hope Hodgson, James Branch Cabell, and many others now considered fantasy classics were brought back into print and released as affordable paperbacks for fantasy-hungry readers. One of Carter’s more obscure finds was the eighteenth book in the series, The Island of the Mighty by Evangeline Walton, a novelistic retelling of the fourth “branch” of the Mabinogion—a series of Welsh-language legends of the British Isles dating from the fourteenth century, the stories themselves most likely originating in the twelfth. Though it had received some critical acclaim on release in 1936 under its original unfortunate (though not inaccurate) title The Virgin and the Swine, it had failed to sell and was pretty well forgotten by the time Carter brought it to Ballantine’s attention.

As explained in publisher Betty Ballantine’s introduction to Overlook’s 2002 omnibus edition of The Mabinogion Tetralogy (also published under the Fantasy Masterworks banner, of which The Island of the Mighty is the fourth and final book, Ballantine’s desire to publish the novel set in motion a heartwarming series of events. Having initially been informed that the book’s copyright had expired, and having searched fruitlessly for Walton, Ballantine prepared the work for publication, finding out at the last minute that the copyright had in fact been renewed, and that Walton was alive and well and living in Phoenix. Walton’s childhood had been marked by illness that kept her in her home, and medical treatments that resulted in a skin condition that would make her reluctant to appear in public later in life. Seeking refuge in books, she developed a love of fantasy and medieval literature, leading to a determination to retell The Mabinogion as a series of fantasy novels.

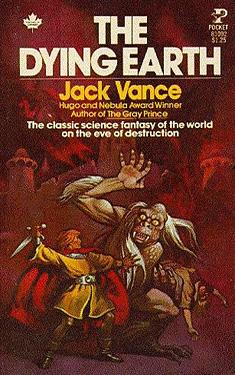

Forays into Fantasy: The Dying Earth by Jack Vance

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Jack Vance creates a subgenre: The Dying Earth

Jack Vance creates a subgenre: The Dying Earth

The work of Grand Master Jack Vance can be segmented into science fiction and fantasy (actually, he wrote some mysteries, too), but they all straddle the borderline between the two genres. Both his fantasy, beginning with The Dying Earth (1950), and his science fiction, beginning with Big Planet (1952), can be seen as the earliest of the modern “planetary romances” – stories set on alien worlds, with plots involving exploration of the sociological and anthropological aspects of these worlds. An important precursor is Clark Ashton Smith, whose tales were often set in far future settings where “technology is indistinguishable from magic,” to borrow Arthur C. Clarke‘s maxim. Leigh Brackett‘s stories of Mars and Venus, in turn influenced by Edgar Rice Burroughs, are also important early examples. These stories are not hard science fiction – the nature of the technology is not a focus of the stories, and there are no technological problems to understand or solve. But they are not pure fantasy either, since they are set on alien worlds or in the far future of Earth, and may include the trappings of SF such as spaceships and aliens.

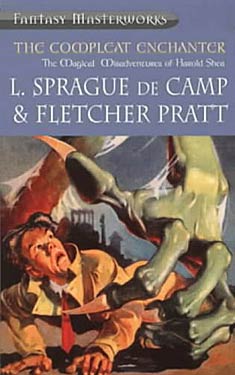

Forays into Fantasy: The Compleat Enchanter by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

In 1939, L. Sprague de Camp, just embarking on a writing career, was introduced to Fletcher Pratt, who had published a number of stories in the science fiction pulps beginning in 1928, while working for Hugo Gernsback as a translator of European SF stories. De Camp became a regular at Pratt’s gatherings based around his elaborate naval war games. When John W. Campbell‘s Unknown fantasy magazine debuted in 1939, Pratt suggested a collaboration between the two authors–a series of novellas "about a hero who projects himself into the parallel worlds described in our world in myths and legends. We made our protagonist a brash, self-conceited young psychologist named Harold Shea," as de Camp explains in his 1975 essay "Fletcher and I."

In 1939, L. Sprague de Camp, just embarking on a writing career, was introduced to Fletcher Pratt, who had published a number of stories in the science fiction pulps beginning in 1928, while working for Hugo Gernsback as a translator of European SF stories. De Camp became a regular at Pratt’s gatherings based around his elaborate naval war games. When John W. Campbell‘s Unknown fantasy magazine debuted in 1939, Pratt suggested a collaboration between the two authors–a series of novellas "about a hero who projects himself into the parallel worlds described in our world in myths and legends. We made our protagonist a brash, self-conceited young psychologist named Harold Shea," as de Camp explains in his 1975 essay "Fletcher and I."

De Camp credits Pratt with the original idea behind the series, and considers him the "senior member" of the collaboration. They brainstormed the plots together, with Pratt providing most of the background for the stories’ mythological and literary settings. De Camp would take notes, and then write a rough draft, which Pratt would turn into a final draft. Lastly, de Camp would make the final edits prior to sending them to Campbell. The stories were a perfect fit for Unknown, where the first three novellas were published in 1940 and 1941. As John Clute and John Grant explain in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Campbell sought to ensure the fantasy elements in Unknown obeyed some set of laws, in effect treating the supernatural as another science."

The title of the second novella, "The Mathematics of Magic" (1940), nicely encapsulates the rationalized approach to fantasy Campbell was looking for in the magazine. In each story, a mental technique developed by a group of psychologists is used to transport Shea and his companions to an alternate universe based on a national mythology or well-known literary setting. As lead psychologist Dr. Chalmers puts it, "the method consists of filling your mind with the fundamental assumptions of the world in question…. If one of these infinite other worlds–which up to now may be said to exist in a logical but not in an empirical sense–is governed by magic, you might expect to find a principle like that of dependence invalid, but principles of magic, such as the Law of Similarity, valid." Our world, in which cause and effect are linked by physical laws (dependence), is then replaced by a world where "effects resemble causes. It’s not valid for us, but primitive peoples firmly believe it. For instance, they think you can make it rain by pouring water on the ground with appropriate mumbo jumbo." By internalizing these magical laws, our heroes not only transport themselves to alternate worlds, but, once achieving a thorough enough understanding of the laws of these worlds, become practicing magicians there.

The title of the second novella, "The Mathematics of Magic" (1940), nicely encapsulates the rationalized approach to fantasy Campbell was looking for in the magazine. In each story, a mental technique developed by a group of psychologists is used to transport Shea and his companions to an alternate universe based on a national mythology or well-known literary setting. As lead psychologist Dr. Chalmers puts it, "the method consists of filling your mind with the fundamental assumptions of the world in question…. If one of these infinite other worlds–which up to now may be said to exist in a logical but not in an empirical sense–is governed by magic, you might expect to find a principle like that of dependence invalid, but principles of magic, such as the Law of Similarity, valid." Our world, in which cause and effect are linked by physical laws (dependence), is then replaced by a world where "effects resemble causes. It’s not valid for us, but primitive peoples firmly believe it. For instance, they think you can make it rain by pouring water on the ground with appropriate mumbo jumbo." By internalizing these magical laws, our heroes not only transport themselves to alternate worlds, but, once achieving a thorough enough understanding of the laws of these worlds, become practicing magicians there.

In the first novella, "The Roaring Trumpet" (1940), Shea, feeling vaguely dissatisfied with his humdrum life in Ohio and yearning for adventure, fires up the "syllogismobile" (his irreverent term for the logical formulations used for inter-universe transportation) for a trip to the world of Irish legend. But Shea has not grasped Dr. Chalmers concepts quite well enough to control the process precisely, and ends up in the wrong legend–that of Norse mythology. Shea is also unprepared for how to make use of magic in this world, but he gradually figures it out, becoming more proficient as he learns how the laws work. This partial understanding of the rules of the worlds he and his companions travel to means that the magic often doesn’t go quite right–the main source of the humor for which the series is known. In "The Mathematics of Magic", Shea and Chalmers, trying to conjure a dragon, get the qualitative aspect of the spell correct, but can’t nail down the quantitative. Instead of one dragon, they get 100; on the second attempt, they get .01 (a mini-dragon). They can’t figure out how to get the decimal point in the right place.

In the first novella, "The Roaring Trumpet" (1940), Shea, feeling vaguely dissatisfied with his humdrum life in Ohio and yearning for adventure, fires up the "syllogismobile" (his irreverent term for the logical formulations used for inter-universe transportation) for a trip to the world of Irish legend. But Shea has not grasped Dr. Chalmers concepts quite well enough to control the process precisely, and ends up in the wrong legend–that of Norse mythology. Shea is also unprepared for how to make use of magic in this world, but he gradually figures it out, becoming more proficient as he learns how the laws work. This partial understanding of the rules of the worlds he and his companions travel to means that the magic often doesn’t go quite right–the main source of the humor for which the series is known. In "The Mathematics of Magic", Shea and Chalmers, trying to conjure a dragon, get the qualitative aspect of the spell correct, but can’t nail down the quantitative. Instead of one dragon, they get 100; on the second attempt, they get .01 (a mini-dragon). They can’t figure out how to get the decimal point in the right place.

In another example, at the end of "The Roaring Trumpet," Shea comes up with a spell to get Heimdall and himself to Ragnarok on time by riding flying broomsticks, but the spell is not precise enough to include a reliable means of controlling their flight:

"Shea gripped the stick till his knuckles were white. Up – up – up he went, till everything was blotted out in the damp opaqueness of cloud. The broom rushed on at a steeper and steeper angle, till Shea found to his horror that it was rearing over backward. He wound his legs around the stick and clung, while the broom hung for a second suspended at the top of its loop with Shea dangling beneath. It dived, then fell over sidewise, spun this way and that, with its passenger flopping like a bell clapper."

These misapplied spells, used for comedic effect, are a hallmark of the stories, and a source of the title of the book that combines the first two novellas, and by which the series itself has come to be known–The Incomplete Enchanter (1941). As for the plot, after becoming magically proficient and helping the Norse gods in the run-up to Ragnarok, Shea is sent home by a witch prior to the world-ending battle. Making better preparations this time, Shea and Chalmers, in "The Mathematics of Magic," travel to the world of Spenser’s The Faerie Queen (1596). While helping Queen Gloriana defeat a cabal of evil magicians (ending with a rather startling scene of magical massacre), Shea meets the huntress Belphebe, who will become his wife and travel with him back to Ohio at story’s end, while Chalmers stays behind, having fallen for a magical doppelganger of Lady Florimel, who he hopes to transform into a real woman once he masters enough magic.

These misapplied spells, used for comedic effect, are a hallmark of the stories, and a source of the title of the book that combines the first two novellas, and by which the series itself has come to be known–The Incomplete Enchanter (1941). As for the plot, after becoming magically proficient and helping the Norse gods in the run-up to Ragnarok, Shea is sent home by a witch prior to the world-ending battle. Making better preparations this time, Shea and Chalmers, in "The Mathematics of Magic," travel to the world of Spenser’s The Faerie Queen (1596). While helping Queen Gloriana defeat a cabal of evil magicians (ending with a rather startling scene of magical massacre), Shea meets the huntress Belphebe, who will become his wife and travel with him back to Ohio at story’s end, while Chalmers stays behind, having fallen for a magical doppelganger of Lady Florimel, who he hopes to transform into a real woman once he masters enough magic.

A third story, "The Castle of Iron," appeared in Unknown in 1941, and was later expanded into a novel published in 1950. The three stories would ultimately be collected in 1975 as The Compleat Enchanter. This time, Chalmers has transported himself from the world of The Faerie Queen to the world of its literary source–Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1532), based on legends of the conflict between Charlemagne’s knights and the Saracens attempting to invade Europe in the eighth century–hoping to get assistance from that world’s sorcerers in restoring Florimel to humanity. In another example of "incomplete enchantment," Chalmers, attempting to snatch Shea from Ohio in order to assist his magical studies, ends up with Belphebe instead. Now in Ariosto’s world instead of Spenser’s, Belphebe becomes Belphagor, the corresponding character in Orlando Furioso, with no memory of her previous adventures or her marriage to Shea. Confined to the eponymous castle by a powerful sorcerer, Shea and his companions must master the rules of Ariosto’s magical world in order to restore Belphebe and Florimel, while avoiding getting caught in the middle of the local conflict. Their misadventures involve, among other magical madness, infantile Paladins, a mistaken werewolf, a hippogriff and a magic carpet, culminating with a storming sorcerers’ battle.

After expanding "The Castle of Iron", de Camp and Pratt went on to publish two more novellas–"The Wall of Serpents" in 1953 and "The Green Magician" in 1954. The full sequence of five eventually appeared as The Complete Compleat Enchanter. (The Fantasy Masterworks version of The Compleat Enchanter also contains all five stories. The NESFA Press collection titled The Mathematics of Magic also includes all the stories, with the addition of two more Shea stories written by de Camp in the early ‘90s.) In "The Wall of Serpents", Shea visits the world of Finnish mythology as described in the Kalevala, and finally makes it to Ireland in "The Green Magician", but the formula has become a little tiresome by that point.

After expanding "The Castle of Iron", de Camp and Pratt went on to publish two more novellas–"The Wall of Serpents" in 1953 and "The Green Magician" in 1954. The full sequence of five eventually appeared as The Complete Compleat Enchanter. (The Fantasy Masterworks version of The Compleat Enchanter also contains all five stories. The NESFA Press collection titled The Mathematics of Magic also includes all the stories, with the addition of two more Shea stories written by de Camp in the early ‘90s.) In "The Wall of Serpents", Shea visits the world of Finnish mythology as described in the Kalevala, and finally makes it to Ireland in "The Green Magician", but the formula has become a little tiresome by that point.

The basic idea is always the same–our heroes arrive in a new world where they must learn the rules of magic in order to help avert a catastrophe and find their way home. The strength of the stories is not in the plotting, but in the comedy and the excitement created by the incidents which tumble on one after another as the stories progress. The stories are also notable for their tone of near-intoxication induced in the characters and reader as a result of the pure exhilaration of their travels into the worlds of magic. (But, as with other sorts of intoxication, it can be overdone, and I was having a hard time continuing with the fourth and fifth novellas, as they began to seem repetitive. This is a series probably best experienced in smaller doses.) As in Silverlock, which also made use of Orlando Furioso as a major source (and whose author, John Myers Myers, was probably influenced by the Shea stories when writing his 1949 novel), immersion in the world of stories is a transformative and life-enhancing experience for characters who feel repressed by their mundane lives. By extension, this idea might be seen to represent the value of fantasy itself to its readers.

Along with being a key exemplar of Unknown-style fantasy, the Incomplete Enchanter sequence also fits into a long tradition of humorous fantasy, stretching back to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and forward to Terry Pratchett. Pratt and de Camp certainly would have known the work of James Branch Cabell and Thorne Smith, published earlier in the century, which mixes mythology, fantasy, and social satire. In turn, de Camp and Pratt would influence the humorous fantasies of Piers Anthony, Robert Asprin, and many others. In the 1990s, Baen would publish two anthologies of new Harold Shea stories by modern authors influenced by the series.

Along with being a key exemplar of Unknown-style fantasy, the Incomplete Enchanter sequence also fits into a long tradition of humorous fantasy, stretching back to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and forward to Terry Pratchett. Pratt and de Camp certainly would have known the work of James Branch Cabell and Thorne Smith, published earlier in the century, which mixes mythology, fantasy, and social satire. In turn, de Camp and Pratt would influence the humorous fantasies of Piers Anthony, Robert Asprin, and many others. In the 1990s, Baen would publish two anthologies of new Harold Shea stories by modern authors influenced by the series.

A major aspect of the comedy in these stories, the inability to control magic, whether as a source of comedy or suspense, also has a long history. For example, consider Goethe’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1798), which became the basis for the Mickey Mouse sequence in Disney’s Fantasia (coincidentally also released in 1940, the same year the Shea sequence began). Shea’s unending procession of dragons is reminiscent of the multiplying brooms and water pails in that story. And the idea that magical spells can be difficult to control, resulting in unintended consequences, became the starting point of nearly every plot in the hundreds of episodes of Bewitched and I Dream of Jeannie. Come to think of it, in this age of CGI, The Magical Misadventures of Harold Shea would probably work pretty well as a sitcom….

Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 by Damien Broderick and Paul Di Filippo

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and has been sharing his experience with his excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy.

Editor’s Note: We held this review back until we finished getting the Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985–2010 list added to the site.

Damien Broderick and Paul Di Filippo’s Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985–2010, presented as a companion to critic/editor David Pringle’s 1985 Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels: An English-Language Selection, 1949–1984, is a worthy successor to the earlier book. Pringle passes the torch in a Foreword to the new volume, admitting that, while a sequel is needed, “Having been unable to keep up with all those new sf works myself, I am delighted that Damien Broderick and Paul Di Filippo have taken it upon themselves to do the job, and I am very happy to endorse their excellent book.”

Damien Broderick and Paul Di Filippo’s Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985–2010, presented as a companion to critic/editor David Pringle’s 1985 Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels: An English-Language Selection, 1949–1984, is a worthy successor to the earlier book. Pringle passes the torch in a Foreword to the new volume, admitting that, while a sequel is needed, “Having been unable to keep up with all those new sf works myself, I am delighted that Damien Broderick and Paul Di Filippo have taken it upon themselves to do the job, and I am very happy to endorse their excellent book.”

Broderick and Di Filippo, for their part, certainly have kept up on the last quarter century of science fiction, and appear to have read just about everything in the earlier era as well. Each entry is laced with references to works (mostly inside, but sometimes out of) the genre, in their efforts to evoke the novel under discussion–both the experience of reading it and its place within the ongoing development of science fiction. For example, Adam Roberts’s Salt is

Like reading Crowley’s “In Blue” as rewritten by Barry Malzberg. It’s like reading Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed as rewritten by Norman Spinrad, or her The Left Hand of Darkness reworked by Ken McLeod (Entry 53). Or Robinson’s Red Mars (Entry 29) altered by Mark Geston. Or Eric Frank Russell’s Wasp redone by Stanislaw Lem. Yes, that strange and enjoyable.

John C. Wright (The Golden Age) is

“the latest of the ambitious deep future New Space Opera boom–David Zindell, Stephen Baxter, Paul McAuley, Iain M. Banks, Peter Hamilton, Alastair Reynolds, Wil McCarthy (most of them with entries in this book)” and is “a sort of extended commentary, from the right, on Olaf Stapledon’s classic, minatory, marxist Last and First Men.”

Similar quotations could be taken from any of the entries, each of which, in a couple of pages, places the relevant novel within the current context, and often in relation to science fiction as a whole–either as a new treatment of a theme the field has been grappling with for decades, or as a reaction against it, or a movement tangential to it. This valuable contextualization is given alongside brief plot and character descriptions, and background about the authors. While occasionally getting bogged down by their density, most of the entries are clear, concise, and evocative, and all are informative.

Reading the entries sequentially, then, we get an episodic history of the last quarter century of science fiction. If I were to try to come up with any general trends after reading the 101 entries, in comparison to the earlier era of Pringle’s book, it would be that stories of space travel migrated into the far future (the New Space Opera mentioned in the Wright entry), while stories of posthumanity came to the fore in medium-term futures. In looking for similarities, both books have their share of alternate histories (more prominent in later years), and dystopias, which never seem to go out of style. It’s also heartening to see the increasing appearance of women authors. Pringle included nine books by women (including two by Le Guin, and only one prior to 1969), compared to about one-third of the authors in the new survey.

Reading the entries sequentially, then, we get an episodic history of the last quarter century of science fiction. If I were to try to come up with any general trends after reading the 101 entries, in comparison to the earlier era of Pringle’s book, it would be that stories of space travel migrated into the far future (the New Space Opera mentioned in the Wright entry), while stories of posthumanity came to the fore in medium-term futures. In looking for similarities, both books have their share of alternate histories (more prominent in later years), and dystopias, which never seem to go out of style. It’s also heartening to see the increasing appearance of women authors. Pringle included nine books by women (including two by Le Guin, and only one prior to 1969), compared to about one-third of the authors in the new survey.

The new list echoes the old in several ways. There is some author overlap (Aldiss, Dick, Vonnegut, Ballard, Moorcock, Poul Anderson, M. John Harrison, Priest, Varley, Stableford, Benford, Octavia Butler, Wolfe, and Gibson), with Brian Aldiss taking the prize for the two most widely-spaced entries–Non-Stop (1958) and HARM (2007)–but that still leaves the vast majority of authors confined to either the pre- or post-1985 eras. Both books begin with a dystopic novel by an author not generally identified with the genre–Orwell’s 1984 for Pringle and Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale for Broderick/Di Filippo. And both end with what are presented as genre-shifting books. In retrospect, Neuromancer looks like a perfect ending point for Pringle’s survey. Whether The Quantum Thief “is the equivalent, for the end of the first decade of the 21st century” remains to be seen, but a good case is made, and the attempt at symmetry must have been irresistible. (Interestingly, William Gibson came close to ending this volume as well, with Zero History being listed second-to-last.)

The opening selections indicate that these critics define the field broadly, and are interested in literary quality as well as novelty or popularity within the more insular genre world. Along with Orwell, Pringle includes books by George R. Stewart, William Golding, Kurt Vonnegut, J. G. Ballard, William S. Burroughs, and Kingsley Amis, alongside Asimov, Heinlein, Silverberg, and Benford. Broderick and Di Filippo take this tendency further, presumably because the use of SF by mainstream writers has only grown in recent decades. (According to their Introduction, readers who prefer to “stick faithfully to their accustomed diversions, preferring yet another franchised episode of Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock or Luke Skywalker and his mean dad, rather as some people eat the same breakfast cereal every day”, or for whom “any attempt by sf writers to adapt [literary] techniques to broaden their canvas and elaborate their palette (or palate) is pretentious or boring or uses ‘too many hard words’,” should look elsewhere for guidance.) This time, we have Atwood, Vonnegut, Jonathan Lethem, Audrey Nifenegger, Philip Roth, Kazuo Ishiguro, Liz Jensen, Cormac McCarthy, and Michael Chabon, side by side with Ian MacDonald, Charles Stross, and Linda Nagata. The authors address the appropriateness of the SF label for some of these books directly, but clearly come down on the side of encouraging and celebrating inclusiveness, and a broad reading of the field, even when the authors themselves resist it. Apparently, for example, Philip Roth claimed to have “no literary models for reimagining the historical past” when writing the alternate history The Plot Against America! But that doesn’t keep it from being an excellent novel, which is what Broderick and Di Filippo are concerned with. (The prize for “the best alternative novel we’ve seen to date”, however, goes to Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union.)

The inclusion of a few novels that hardcore SF fans might argue with should be a little easier to accept given that the authors have found a way to expand their net beyond the 101 novels of the title. Yes, there are 101 entries, each associated with a particular novel, but, unlike in the Pringle survey, no author gets more than one entry, leaving room for a much larger variety of books. Doesn’t this mean that this is not really the “101 Best Novels”, but rather the 101 best authors? Yes and no. A strict list of the best novels would likely contain more than one entry for some authors (Pringle, for example, was especially partial to Dick, Ballard, and Aldiss), but many of the entries in Broderick and Di Filippo’s book are really about duologies, trilogies, series, or even an authors’ entire output, thus providing information and commentary on many more than the 101 novels indicated in the title. For example, the Perdido Street Station entry discusses entire Bas Lag sequence, Paul Park’s Soldiers of Paradise recommends the entire Starbridge Chronicles, and the Neal Stephenson entry explains first why, in choosing a representative novel, the authors’ narrowed his oeuvre down to Snow Crash and The Diamond Age, and then why they ultimately settled on the latter over the former. In each case, while a single novel is focused on, the lens is often pulled back for a more wide-angle discussion of a significant chunk of an author’s output, when appropriate.

The inclusion of a few novels that hardcore SF fans might argue with should be a little easier to accept given that the authors have found a way to expand their net beyond the 101 novels of the title. Yes, there are 101 entries, each associated with a particular novel, but, unlike in the Pringle survey, no author gets more than one entry, leaving room for a much larger variety of books. Doesn’t this mean that this is not really the “101 Best Novels”, but rather the 101 best authors? Yes and no. A strict list of the best novels would likely contain more than one entry for some authors (Pringle, for example, was especially partial to Dick, Ballard, and Aldiss), but many of the entries in Broderick and Di Filippo’s book are really about duologies, trilogies, series, or even an authors’ entire output, thus providing information and commentary on many more than the 101 novels indicated in the title. For example, the Perdido Street Station entry discusses entire Bas Lag sequence, Paul Park’s Soldiers of Paradise recommends the entire Starbridge Chronicles, and the Neal Stephenson entry explains first why, in choosing a representative novel, the authors’ narrowed his oeuvre down to Snow Crash and The Diamond Age, and then why they ultimately settled on the latter over the former. In each case, while a single novel is focused on, the lens is often pulled back for a more wide-angle discussion of a significant chunk of an author’s output, when appropriate.

I suppose the final question should be: Are these really the 101 best novels of the last quarter century? The appropriate answers could be: “of course not”; “I don’t know”; or, “it doesn’t matter”. (For a question like this, I don’t think “yes” or “no” really apply.) Answer number one: Of course not, because everyone’s take on the best novels will be different. A good reviewer will find a way to give you enough of the sense of a book to decide whether you might be interested in it, and I think Broderick and Di Filippo do this very well. Answer number two: I don’t know, because I haven’t read the vast majority of these novels myself. I was greatly looking forward to this book because I’m a fan of Pringle’s 100 Best, and because I’ve read very little SF from the period the new book covers, and have been looking for a guide back into the field. After reading it, I’m pretty certain their critical take on the field will match my tastes reasonably well, but I’m sure others will see a lot of their favorites missing and thus decide they have little use for it–a perfectly valid response. (The fact that they include several of my favorites from the recent period that I’ve been back reading the field– Zero History, Windup Girl, Zoo City, and Quantum Thief–adds to my confidence that I’ll like lots of others on this list.)

Finally, answer number three, and the one I prefer: It doesn’t matter whether these are really the 101 Best Novels, because the book still succeeds as an interesting survey of what’s been happening in the science fiction field during the period covered, and because, even for those whose tastes don’t jibe with the authors’, such lists always serve to start an interesting debate. Other “best of” lists from well-read critics, along with surveys based on the opinions of fans and general readers, will always differ (sometimes greatly), keeping the debate going. (Worlds Without End, of course, contains lots of them!) As readers, the trick is to find those that best match our tastes and inclinations. In my case, I’m looking for a wide-ranging and challenging critical survey, and this one seems a good guide to the period. Broderick and Di Filippo succeeded in getting me interested in dozens of books that I knew little about or, in some cases, hadn’t even heard of. List-lovers should read it, enjoy it, and argue with it.

Finally, answer number three, and the one I prefer: It doesn’t matter whether these are really the 101 Best Novels, because the book still succeeds as an interesting survey of what’s been happening in the science fiction field during the period covered, and because, even for those whose tastes don’t jibe with the authors’, such lists always serve to start an interesting debate. Other “best of” lists from well-read critics, along with surveys based on the opinions of fans and general readers, will always differ (sometimes greatly), keeping the debate going. (Worlds Without End, of course, contains lots of them!) As readers, the trick is to find those that best match our tastes and inclinations. In my case, I’m looking for a wide-ranging and challenging critical survey, and this one seems a good guide to the period. Broderick and Di Filippo succeeded in getting me interested in dozens of books that I knew little about or, in some cases, hadn’t even heard of. List-lovers should read it, enjoy it, and argue with it.

Full Details

Full Details