Forays into Fantasy: Edgar Rice Burroughs One-Hundred Years On

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

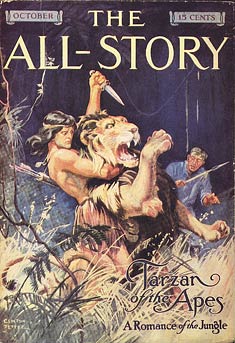

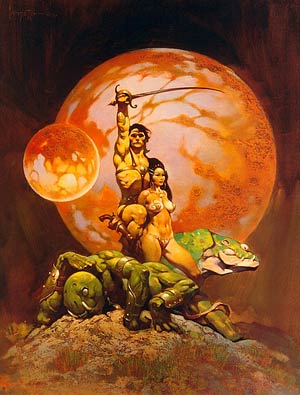

Around age eleven, Edgar Rice Burroughs was my favorite writer, and I devoured all of his books I could find. Rereading Burroughs’ first two novels today–A Princess of Mars (originally serialized in 1912 as "Under the Moons of Mars") and Tarzan of the Apes (serialized later in 1912), both of which have just been reprinted in beautiful facsimile editions by the Library of America–it’s harder to overlook the weaknesses, but the appeal remains clear. The prose is often awkward, incredible plot coincidences abound, relationships are simplistic, race and gender assumptions are problematic (more on that below), yet all these problems are (mostly) redeemed in the best of Burroughs’s novels by the relentless storytelling imagination and energy at work. Over one-hundred million copies sold, and counting…

Around age eleven, Edgar Rice Burroughs was my favorite writer, and I devoured all of his books I could find. Rereading Burroughs’ first two novels today–A Princess of Mars (originally serialized in 1912 as "Under the Moons of Mars") and Tarzan of the Apes (serialized later in 1912), both of which have just been reprinted in beautiful facsimile editions by the Library of America–it’s harder to overlook the weaknesses, but the appeal remains clear. The prose is often awkward, incredible plot coincidences abound, relationships are simplistic, race and gender assumptions are problematic (more on that below), yet all these problems are (mostly) redeemed in the best of Burroughs’s novels by the relentless storytelling imagination and energy at work. Over one-hundred million copies sold, and counting…

Burroughs was the most popular fantastic writer of the first third of the twentieth century, and it was during this period that the fantastic became “ghettoized” as it moved into the realm of the pulps, while mainstream writers for the most part stopped delving into the fantastic. As Paul Kincaid writes in “American Fantasy 1820–1950” (in The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature):

“By the 1920s and 1930s the freedom that had allowed Jack London [and, earlier, Mark Twain or Henry James, among others] to move readily between realism and the fantastic was becoming more restricted. A mode now most readily identified with the smutty comedies of [Thorne] Smith and [James Branch] Cabell or, more damningly, with the grotesque horrors of Lovecraft and the crude, highly coloured adventures of [Robert E.] Howard could not be employed for serious literary purposes.”

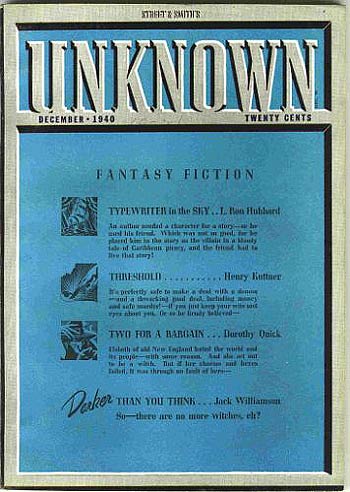

As reading for pleasure became more widespread due in part to the development of low-cost “dime novels” and pulp magazines, the literary divide widened. The three main branches of the pulp fantastic were exemplified and inspired by Burroughs’ “science fantasy” adventures, Howard’s sword and sorcery (Conan, etc.), and Lovecraft’s weird fiction. Writers with serious literary ambitions no longer wanted to be associated with a mode of writing increasingly linked to the pulps.

Burroughs got started earlier than Lovecraft or Howard and, reading him today, I think of him as the ultimate pulp writer–embodying both the positive and negative aspects of those early magazines, as well as informing all who would follow in his footsteps. Burroughs famously turned to writing relatively late, his military ambitions during the 1890s having been quashed. He failed to get into West Point or to be chosen as one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, but did spend some time in the cavalry in Arizona before being discharged for health reasons–an experience that helped inform the opening chapters of Princess–before attempting and abandoning a series of business ventures during the 1900s. He tried writing in part out of desperation, needing to support his young family, after reaching the conclusion that he could write better stories than the majority he was reading in the pulps of the time. (He was right!) His two best-known novels, both of which would spawn long-running series, both appeared in The All-Story magazine in 1912, the year Burroughs turned thirty-seven.

Burroughs got started earlier than Lovecraft or Howard and, reading him today, I think of him as the ultimate pulp writer–embodying both the positive and negative aspects of those early magazines, as well as informing all who would follow in his footsteps. Burroughs famously turned to writing relatively late, his military ambitions during the 1890s having been quashed. He failed to get into West Point or to be chosen as one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, but did spend some time in the cavalry in Arizona before being discharged for health reasons–an experience that helped inform the opening chapters of Princess–before attempting and abandoning a series of business ventures during the 1900s. He tried writing in part out of desperation, needing to support his young family, after reaching the conclusion that he could write better stories than the majority he was reading in the pulps of the time. (He was right!) His two best-known novels, both of which would spawn long-running series, both appeared in The All-Story magazine in 1912, the year Burroughs turned thirty-seven.

By his death in 1950, Burroughs had, in the prolific pulp tradition, published nearly seventy novels, and several more appeared posthumously. Along with the Barsoom (Mars) series, which eventually included eleven books, and the Tarzan series (twenty-four books), the trilogy beginning with The Land That Time Forgot probably remains best-known today. In addition, he wrote the Carson of Venus series, the Pellucidar hollow-Earth series beginning with At the Earth’s Core (which included a Tarzan crossover) and numerous other genre stories, as well as a few attempts at Westerns and contemporary fiction. To my mind, Burroughs peaked in the 1920s, with novels like Tarzan the Untamed (1920) and The Chessmen of Mars (1922), and both series are worth pursuing for readers who enjoy the opening books. After the ‘20s, however, diminishing returns set in, as will be clear to anyone who attempts to get through the last few volumes of the two series, or compares the tired-seeming Venus novels (1934–1946) to the earlier Mars books. Even as an enthusiastic adolescent, I think I gave up after sixteen or eighteen Tarzan novels.

Tarzan, of course, would live on in films, television, and comics, most of which greatly annoyed fans of the books, since they tended to leave out the more fantastic aspects (ancient lost cities, underground civilizations, dinosaurs, immortality drugs), but most importantly because they deemphasized the most interesting aspect of Tarzan’s character–his dual existence as a primordial jungle denizen and a highly intellectual English aristocrat. The combination makes him a superman. (And certainly, one of the impacts of the popularity of Tarzan and other pulp heroes would be on the creation of superhero comics beginning in the late ‘30s.)

Tarzan, of course, would live on in films, television, and comics, most of which greatly annoyed fans of the books, since they tended to leave out the more fantastic aspects (ancient lost cities, underground civilizations, dinosaurs, immortality drugs), but most importantly because they deemphasized the most interesting aspect of Tarzan’s character–his dual existence as a primordial jungle denizen and a highly intellectual English aristocrat. The combination makes him a superman. (And certainly, one of the impacts of the popularity of Tarzan and other pulp heroes would be on the creation of superhero comics beginning in the late ‘30s.)

Tarzan is really Lord Greystoke, whose parents were stranded on the African coast following a mutiny by the crew of the ship they were traveling on. Lady Alice died soon after, leaving a despairing father with no way to feed the infant. When a band of great apes–an invented species that seems to be the “missing link” between apes and humanity, with the rudiments of a spoken language–breaks into the cabin and kills Lord Greystoke, a female ape who had just lost her own baby adopts the boy and forces the rest of the band to tolerate Tarzan (“white skin” in the ape language) and allow her to raise him as one of them.

Despite having no direct contact with people, Tarzan does gain access to his parents’ cabin. Sitting with their skeletons, he discovers books, including, crucially, an illustrated dictionary, and his hereditary intelligence kicks in as he, amazingly, teaches himself to read. Once he started to identify groups of letters with accompanying pictures, “his progress was rapid… and the active intelligence of a healthy mind endowed by inheritance with more than ordinary reasoning powers” took over. For Burroughs, the aristocratic white man is clearly the peak of evolution, and even being brought up by apes cannot prevent the “higher” qualities from asserting themselves. Later, meeting Jane Porter brings his hereditary nature to the fore: “It was the hall-mark of his aristocratic birth, the natural outcropping of many generations of fine breeding, and hereditary instinct of graciousness which a lifetime of uncouth and savage training could not eradicate.” The impact of heredity and environment, and the conflicting appeals of his own kind and jungle life, will remain central to Tarzan’s character.

In A Princess of Mars, John Carter is similarly presented as a superior white aristocrat (an American southerner, in his case), who becomes the greatest man on Mars, just as Tarzan surpasses the rest of humanity due to his superior intelligence and character. Carter’s “features were regular and clear cut, his hair black and closely cropped, while his eyes were of a steel grey, reflecting a strong and loyal character, filled with fire and initiative. His manners were perfect, and his courtliness was that of a typical southern gentleman of the highest type.” Even his family’s slaves “fairly worshipped the ground he trod”! All in all, Carter is a “splendid specimen of manhood,” irresistible to the aristocratic Barsoomian princess Dejah Thoris: “Was there ever such a man! she exclaimed. ‘I know that Barsoom has never before seen your like… Alone, a stranger, hunted, threatened, persecuted, you have done in a few short months what in all the past ages of Barsoom no man has ever done.” As for Tarzan, Jane “noted the graceful majesty of his carriage, the perfect symmetry of his magnificent figure and the poise of his well shaped head upon his broad shoulders. What a perfect creature! There could be naught of cruelty or baseness beneath that godlike exterior. Never, she thought, had such a man strode the earth since God created the first in his own image.”

In A Princess of Mars, John Carter is similarly presented as a superior white aristocrat (an American southerner, in his case), who becomes the greatest man on Mars, just as Tarzan surpasses the rest of humanity due to his superior intelligence and character. Carter’s “features were regular and clear cut, his hair black and closely cropped, while his eyes were of a steel grey, reflecting a strong and loyal character, filled with fire and initiative. His manners were perfect, and his courtliness was that of a typical southern gentleman of the highest type.” Even his family’s slaves “fairly worshipped the ground he trod”! All in all, Carter is a “splendid specimen of manhood,” irresistible to the aristocratic Barsoomian princess Dejah Thoris: “Was there ever such a man! she exclaimed. ‘I know that Barsoom has never before seen your like… Alone, a stranger, hunted, threatened, persecuted, you have done in a few short months what in all the past ages of Barsoom no man has ever done.” As for Tarzan, Jane “noted the graceful majesty of his carriage, the perfect symmetry of his magnificent figure and the poise of his well shaped head upon his broad shoulders. What a perfect creature! There could be naught of cruelty or baseness beneath that godlike exterior. Never, she thought, had such a man strode the earth since God created the first in his own image.”

The racial implications are uncomfortable to the modern reader, but they are not as simplistically racist as they might at first appear. Both characters are the only white men in their respective worlds, and this is seen as a source of their superiority. Yet both are more at home in their adopted worlds than with their own kind. The racism is accompanied by the idea that the “lower” races (apes, blacks, Tharks, etc.) have positive qualities that have been lost by modern “civilized” whites. Carter is more at home with the green Tharks and red Martians, just as Tarzan feels the pull of jungle life whenever he returns to the constraints of civilization. And, despite the implication of miscegenation, Carter marries red-skinned Dejah Thoris, and the couple’s son will hatch from an egg. (Exactly how this works is happily never explained, and this is the sort of thing that, to me, makes Burroughs a fantasy rather than a science fiction writer.)

Carter is the embodiment of the Western hero suited for a frontier life–a life no longer available to him at home, but possible on Barsoom, which can be seen as an extension of the “manly” frontier life Burroughs himself had longed for in his military years. And Tarzan’s superiority to other men is not just because he is a white aristocrat in black Africa, but also because his upbringing by the apes has freed him from the constraints of civilization. Thus, it is the combination of heredity and upbringing that makes him superior to both Africans and whites. After learning the ways of civilization, which Tarzan/Greystoke takes to quite easily, he never loses the call of the wild.

Carter is the embodiment of the Western hero suited for a frontier life–a life no longer available to him at home, but possible on Barsoom, which can be seen as an extension of the “manly” frontier life Burroughs himself had longed for in his military years. And Tarzan’s superiority to other men is not just because he is a white aristocrat in black Africa, but also because his upbringing by the apes has freed him from the constraints of civilization. Thus, it is the combination of heredity and upbringing that makes him superior to both Africans and whites. After learning the ways of civilization, which Tarzan/Greystoke takes to quite easily, he never loses the call of the wild.

“Tarzan had no sooner entered the jungle than he took to the trees and it was with a feeling of exultant freedom that he swung once more through the forest branches. This was life! Ah, how he loved it! Civilization held nothing like this in its narrow and circumscribed sphere, hemmed in by restrictions and conventionalities. Even clothes were a hindrance and a nuisance. At last he was free. He had not realized what a prisoner he had been.”

Throughout the series, Greystoke would be drawn back to civilization by his family and hereditary obligations, but he would always long for and ultimately return to the jungle–his true home. Similarly, at the end of A Princess of Mars, when Carter returns to Earth as mysteriously as he had originally appeared on Mars, all he can think of is his desire to return to the dying red planet. “I can see her shining in the sky through the little window by my desk, and tonight she seems calling to me again.” He, too, will return for the sequel.

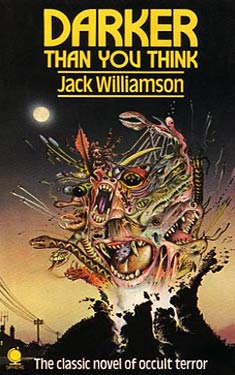

Tarzan became one of the best known character creations of the twentieth century, but it is Barsoom that would have the biggest impact on fantasy and science fiction. Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, with its dying planet crisscrossed with canals and home to ancient ruins of once-great civilizations, can be traced back to Burroughs, as can the entire subgenre of science fantasy and planetary romance, as traced through the works of Leigh Brackett (Sea-Kings of Mars), Jack Vance (Big Planet), Michael Moorcock (the Michael Kane trilogy), Gene Wolfe (The Book of the New Sun), George Lucas (Star Wars), and countless others. In a planetary romance, the alien planet and its exploration are important aspects of the story; the means of getting there are not. In Princess, Carter, longing to reach Mars, “stretched out my arms toward the god of my vocation and felt myself drawn with the suddenness of thought through the trackless immensity of space.” Such stories are often marketed as science fiction, but they are distinguished from fantasy only in that the imaginary settings are on other planets rather than undefined earthly realms like Middle Earth or Westeros.

Burroughs’s influence, then, arises from the subgenre he pioneered–exciting adventure stories set in fantastic locales with one foot in reality, and he is seen as the progenitor of science fantasy and the planetary romance. But is he still worth reading? The books have not avoided becoming dated (Tarzan more so than Barsoom), but Burroughs is a natural storyteller, and it’s easy to see why these books were so compelling to legions of readers over the years, especially younger readers like my ten-year-old self, for which Burroughs has served as a major gateway into fantasy and science fiction. It could be argued that genre readers no longer need to bother with Burroughs, but if so, this is because his influence has been so thoroughly absorbed into the field, even those who haven’t read the originals have still, in a sense, internalized them by reading so many works influenced by them. Apparently, one of the criticisms of the recent John Carter film was that, for many viewers, it seemed overly familiar and unoriginal. This is the potential fate of the most influential stories–decades of homage and imitation can make the original seem unoriginal!

Burroughs’s influence, then, arises from the subgenre he pioneered–exciting adventure stories set in fantastic locales with one foot in reality, and he is seen as the progenitor of science fantasy and the planetary romance. But is he still worth reading? The books have not avoided becoming dated (Tarzan more so than Barsoom), but Burroughs is a natural storyteller, and it’s easy to see why these books were so compelling to legions of readers over the years, especially younger readers like my ten-year-old self, for which Burroughs has served as a major gateway into fantasy and science fiction. It could be argued that genre readers no longer need to bother with Burroughs, but if so, this is because his influence has been so thoroughly absorbed into the field, even those who haven’t read the originals have still, in a sense, internalized them by reading so many works influenced by them. Apparently, one of the criticisms of the recent John Carter film was that, for many viewers, it seemed overly familiar and unoriginal. This is the potential fate of the most influential stories–decades of homage and imitation can make the original seem unoriginal!

Next up: The Enchanter stories of L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt…

Forays into Fantasy: Silverlock by John Myers Myers

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

John Myers Myers‘s Silverlock, published in 1949, is a recursive fantasy–a fantasy that makes use of settings or characters created by other authors, emphasizing the mutual influence and interrelatedness of all literature. Myers takes this conceit to its extreme, setting the novel on an island known as the Commonwealth–a reference to our shared inheritance of fictional and historical stories referred to by Joseph Addison as the "commonwealth of letters." In the Commonwealth, all stories coexist. The setting of Silverlock is all of literature and history!

John Myers Myers‘s Silverlock, published in 1949, is a recursive fantasy–a fantasy that makes use of settings or characters created by other authors, emphasizing the mutual influence and interrelatedness of all literature. Myers takes this conceit to its extreme, setting the novel on an island known as the Commonwealth–a reference to our shared inheritance of fictional and historical stories referred to by Joseph Addison as the "commonwealth of letters." In the Commonwealth, all stories coexist. The setting of Silverlock is all of literature and history!

In the first few chapters, Clarence Shandon, traveling on the Naglfar (the ship piloted by Loki during Ragnarok in Norse mythology), is shipwrecked. Assisted by Golias, who will become Shandon’s friend and guide, and who is also adrift in the ocean for reasons unknown, they witness the appearance of Moby Dick sinking the Pequod, after which they are able to make their way to the island of Aeaea, off the coast of the Commonwealth. Aeaea is the home of Circe (see Greek mythology for the details), who turns Shandon into a pig after he makes a pass at her. Golias helps him escape the island (and the influence of Circe’s spell), and they manage to swim to Robinson Crusoe’s island, where they are nearly captured by cannibals. Escaping in one of their kayaks, they nearly die of thirst before being picked up by a Viking ship, on their way to fight in the Battle of Clontarf (which took place when the Vikings invaded Ireland in 1014). Shandon is recruited as a rower, and he and Golias end up participating in the battle, barely escaping when the Vikings are routed. Separated from Golias, Shandon (now known as Silverlock, after the streak of premature gray in his hair) soon encounters Robin Hood and his men, helps Rosalette (a composite of Rosalind from As You Like It and Nicolette from the thirteenth-century French chantefable Aucassin and Nicolette) reunite with her lover, and joins the Mad Tea Party from Alice in Wonderland, among other adventures. After these travels, he manages to rendezvous with Golias, who is found in a tavern with Beowulf, celebrating the destruction of Grendel.

And all of this happens in the first third of the book. It’s the kind of novel that’s difficult to summarize without recounting too much detail, since it is so packed with incident and character, but I wanted to provide a taste of what the reading experience is like, and the way Myers combines story elements. A summary of the plot details, however, really misses the point. Instead, consider the main character. Shandon is a prototypical mid-twentieth century pragmatic American. When he is shipwrecked, he has little interest in saving himself, having become cynical and uninterested in life. "My only philosophy, if you could call it that, had been a contempt for life backed by a pride in that contempt." He is an educated man, but is clearly not the type to spend time with trivialities like art and literature. His arrival in the Commonwealth, however, plunges him into the world of stories, where he is ultimately transformed and enlightened by his exposure to the world of literature and history–in other words, the essence of human experience–and learns to reconnect with his humanity and regain a zest for living.

It’s not an easy path. At first he resists Golias’s attempts to involve him in his adventures. (I should note that Golias is a composite of various bard, minstrel, poet, and storyteller characters, and is referred to by many names throughout the novel.) He reluctantly agrees to assist a friend of Golias to claim his love and regain his inheritance, shamed into it by the presence of Beowulf, the ultimate hero. "Remembering what he had done to help out strangers, I simply could not let him hear me say that I would back out on a friend who was asking my help." The reform of his character has begun. The subsequent picaresque adventure occupies the second third of the novel, during which many other literary and historical figures are encountered. (Favorite incidents include an attempt to placate Don Quixote, and a trip on Huck Finn’s raft).

Mission accomplished, Golias unexpectedly tells Silverlock that they must separate. Shandon, who has finally gotten used to taking pleasure in the company of others, and thinks of Golias as his new best friend, doesn’t take it well, and his selfish reaction indicates that he still has some things to learn. Continuing to wander through the Commonwealth on his own, feeling bitter and cynical, his encounters become increasingly dark. He takes a ride on the Ship of Fools, runs into Job from the Old Testament (whose suffering makes it more difficult for Silverlock to feel sorry for himself), and is taken down into the Pit by "Faustophelese," where he encounters numerous examples of the dark side of human nature, along with other hellish denizens from various mythologies and Dante’s Inferno. His soul in danger, Silverlock is again rescued by Golias, now in the guise of Orpheus, and sent to drink from the spring of Hippocrene, the well of poetic inspiration in Greek myth. He doesn’t achieve the status of poet, but drinking from the spring allows him to remember his experiences in the Commonwealth, and receive passage back to his own world. He is taken aloft by Pegasus, and dropped into the ocean to be picked up by a passing ship.

Silverlock, then, is an allegory, but it’s much more fun than A Pilgrim’s Progress, as it includes much more drinking and singing. Shandon regains the joy of life, and Myers portrays that joy throughout. It’s a novel that shouldn’t work, yet does, and I put this down to the novel’s unique narrative perspective. The Commonwealth is not a fantasy setting in the usual sense. Those who read fantasy for the world-building aspect are likely to be disappointed, because this world makes no sense. Stories and characters from different historical periods coexist side by side, but the Vikings fight with bows, spears, and longships, oblivious to the fact that guns and steamboats are being used a few miles away. When Shandon encounters all of these characters and settings, he accepts them, never bringing up the fact that they are from stories. His pragmatic mind simply accepts the Commonwealth for what it is, and he never considers that his encounters seem designed to teach him lessons in living. This method allows the story to exist on several levels. The novel is narrated by Shandon, and from that direct perspective, Silverlock is a rollicking, rapidly-paced adventure story, full of excitement and interesting encounters, and can be enjoyed as such by readers mostly unaware of the literary allusions.

But for the reader with literary experience, those allusions provide another level of enjoyment. Since events are being described by someone entirely unfamiliar with the original stories, the reader must often identify the allusions without characters and settings being directly mentioned, but only described. For example, at one point Shandon and Golias find a raft and use it to travel toward their destination more quickly than they could on foot. The description of the river and their feelings while on the raft will identify it pretty quickly to anyone who has read Huckleberry Finn, but that story is never mentioned. Encountering Robin Hood or Don Quixote, Shandon doesn’t react by remembering the characters from a book or a movie, but his descriptions of their appearance and behavior will identify them to those familiar with the stories.

And I can guarantee that no reader will be familiar with all the stories. Nearly every detail in the book is taken from another story. Knowing that, I found myself continually trying to figure out the sources based on the descriptions in the novel, since they are not directly identified, and are often composites of similar characters from different stories (as in the case of Golias). This literary guessing game will be an enjoyable challenge for some readers, and is a big reason for the book’s cult following. Anyone trying to "get" all the references is bound to be disappointed, but the wonderful thing about Myers’s narrative method is that the novel can be enjoyed without getting them, so the reader can engage with that aspect of the novel to whatever degree she cares to.

And I can guarantee that no reader will be familiar with all the stories. Nearly every detail in the book is taken from another story. Knowing that, I found myself continually trying to figure out the sources based on the descriptions in the novel, since they are not directly identified, and are often composites of similar characters from different stories (as in the case of Golias). This literary guessing game will be an enjoyable challenge for some readers, and is a big reason for the book’s cult following. Anyone trying to "get" all the references is bound to be disappointed, but the wonderful thing about Myers’s narrative method is that the novel can be enjoyed without getting them, so the reader can engage with that aspect of the novel to whatever degree she cares to.

For anyone thinking of reading Silverlock, I strongly recommend getting the NESFA Press edition, which is still in print, since, along with being a beautiful book, it contains The Silverlock Companion, a hundred and fifty pages of supplementary material including, most importantly, "A Reader’s Guide to the Commonwealth," a concordance of the literary allusions. Coming across an unfamiliar character or place, it can be looked up in the guide and the original source identified. Along with discovering literary antecedents I was unaware of, or only vaguely aware of, this additional background added to my understanding of Myers’s reasons for choosing the stories for Silverlock to interact with, in relation to his own progress as a character. Browsing through this compendium of eighteenth and nineteenth century novels, Greek, Norse, Irish, Icelandic, and Chinese myths and legends, American tall tales, and Old English poetry, Myers’ amazing achievement is brought home. (And those examples just scratch the surface. There are hundreds of stories referenced in Silverlock.) His goal, however, is not to point out his own erudition, but rather to celebrate the role of stories in our lives. His story–Silverlock–is just one more small region to be annexed by the Commonwealth. Instead, he wants to remind us of the beauty–dramatic, comedic, tragic, romantic, fantastic–of the literary and historical heritage of humanity. Like Shandon, we can’t stay in the Commonwealth forever, but visiting it will enrich our lives by providing access to people, ideas, and experiences that enrich our understanding and enjoyment of life.

So, where does Silverlock fit in the history of fantastic literature? As mentioned above, it can be seen as a major exemplar of recursive fantasy, and many of its sources are the wellsprings of the fantastic–ancient myths, fairy tales, Arthurian legends, Beowulf, Dante’s Inferno…–thus being in a sense a fantasy about the fantastic. But since the narrator, Shandon, is unaware of the nature of the fantasy world he has entered, it does not come across as self-aware metafiction. As far as I know, then, Silverlock is unique in the history of fantasy. While there are plenty of other examples of recursive fantasy (Myers was probably influenced by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Incomplete Enchanter, for example), none that I know of operate in the way the Silverlock does. (If anyone knows of anything similar, I’d like to hear about it.)

Its uniqueness may explain its relative obscurity. As Myers wrote in 1980: "This was to be my big book, my contribution to the ages, and it flopped all over the place. Although it has since been revived by Ace in 1966, and again in 1979–it was an egg laid by an ostrich when it first came out and was remaindered." It’s been championed by its fans–Poul Anderson, Larry Niven, and Jerry Pournelle each wrote introductions to the 1979 edition–but it seems to be something of a cult item today, not well known to the community of fantasy readers, but extremely well-loved by those who do know it and appreciate it. According to David Pringle, who includes it in his Hundred Best, Myers "has produced a strange, harshly whimsical and rumbustious book… It will not be to every reader’s taste, but it is memorably different."

Its lack of success may have had to do with its timing. Prior to the 1920s, fantasy as a genre had yet to be ghettoized. Hawthorne, Melville, Henry James, Mark Twain, and Jack London all wrote fantasy without readers raising an eyebrow. It was just one of a number of fictional strategies used by these writers. By the time Silverlock was published, however, fantasy had mostly been relegated to the pulps. Silverlock, as a literary fantasy arriving in 1949, was ignored by the mainstream, simply because it was fantasy, while not being the sort of thing to interest the majority of the genre audience. In retrospect, we can ignore the genre prejudices and see it as part of a larger flowering of fantasy in the ‘40s and ‘50s that included, in America, de Camp and Pratt, Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser sequence; and, in the United Kingdom, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, and, of course, J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Despite being the least well-known of these contemporaries, it deserves to be considered among them.

The Drowned Cities by Paolo Bacigalupi

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for some good books to read. Luckily for us he decided to stay awhile and write some reviews. He recently launched a new blog series for us called Forays into Fantasy in which he explores the roots of the fantasy genre from a science fiction fan’s perspective.

In The Drowned Cities, Paolo Bacigalupi returns to the future America first envisioned in his 2010 young adult novel, Ship Breaker, enriching it by moving beyond his typical environmental concerns into a meditation on dysfunctional politics. Bacigalupi has said in interviews that, after a lot of work, he abandoned the attempt to write a direct sequel to Ship Breaker. Instead, The Drowned Cities introduces new characters to guide the reader further into the same world. Moving north from the setting of the previous novel, The Drowned Cities are what remains of Washington, D. C. and its environs, now engulfed by the rising ocean. Military forces led by competing warlords fight for control of the area, using conscripted child soldiers.

In The Drowned Cities, Paolo Bacigalupi returns to the future America first envisioned in his 2010 young adult novel, Ship Breaker, enriching it by moving beyond his typical environmental concerns into a meditation on dysfunctional politics. Bacigalupi has said in interviews that, after a lot of work, he abandoned the attempt to write a direct sequel to Ship Breaker. Instead, The Drowned Cities introduces new characters to guide the reader further into the same world. Moving north from the setting of the previous novel, The Drowned Cities are what remains of Washington, D. C. and its environs, now engulfed by the rising ocean. Military forces led by competing warlords fight for control of the area, using conscripted child soldiers.

Mahlia is a “castoff”–child of an African-American antiquities dealer and a Chinese peacekeeper. The peacekeepers attempted for over a decade to end the ongoing civil conflicts and promote economic development in the Drowned Cities, but eventually abandoned the effort. Mahlia’s father left with the rest of the peacekeepers, abandoning Mahlia and her mother, who is killed when the natives turn on everyone who had “collaborated” with the Chinese, including their castoff children. Mahlia loses a hand in the violence, but manages to escape due to the impulsive actions of a former farm boy named Mouse, who is also trying to survive in this violent world, having lost his parents to the fighting. Now inseparable, the two are adopted by Doctor Mahfouz, who is trying to help maintain a semblance of civilization in this fallen world, practicing medicine and stockpiling books from ruined libraries in the rural community of Banyan Town. Training her as a medical assistant, it is only his protection that keeps Mahlia relatively safe from the town’s hatred of castoffs. Their lives, already precarious, are disrupted by their discovery of the injured Tool–the one character carried over from Ship Breaker–who is on the run from soldiers of the United Patriot Front (UPF), who value him as an entertaining participant in their arena fighting tournaments. Tool is an “augment”–a genetically engineered fighting machine with human, hyena, dog, and tiger DNA. A fascinating character creation, it’s understandable that Bacigalupi wanted to explore him further.

When a band of UPF soldiers arrives, hunting for Tool, Banyan Town is caught in the middle, with serious consequences for the town, for Doctor Mahfouz, and for Mouse, who narrowly escapes death but is recruited by the UPF and forced to become a “soldier boy.” To what extent is Mahlia, who treated Tool’s injuries and refused to turn him over to the soldiers, responsible for these tragedies? Throughout the book, Bacigalupi plays with the ambiguity of responsibility in such extreme circumstances. In the midst of a war, to what extent can she be held responsible for the soldiers’ reactions in response to her refusal to give in to their demands? For that matter, to what extent are soldiers responsible for the violence they perpetrate under orders, especially when those soldiers are children who cannot survive outside of the “family” provided by their platoons? Ocho, a UPF soldier who, before the end of the novel, must make his own choice about perpetuating the cycle of war that has made him both a victim and a victimizer, defends the soldier boys, while recognizing the evil they are caught up in: “None of us asked for this! …None of us were like this…. We aren’t born like this. They make us this way.”

Unable to abandon the boy who at one time rescued her and attempting to make up for her role in these events, Mahlia makes what seems to be a suicidal decision to track Mouse into the Drowned Cities and rescue him from the UPF. Thus begins the adventure that makes up the second half of the novel, as well as Mahlia’s personal journey toward an understanding of the complexities of personal morality in a world where individuals are constrained by a dysfunctional society. Tool, who has his own scores to settle, accompanies her, their uneasy alliance growing as the novel progresses.

Like Ship Breaker, which won the Printz Award for best YA novel from the American Library Association and the 2011 Locus YA award, and was nominated for the National Book Award in the YA category, The Drowned Cities is being marketed as a young adult book, but it is a darker and more brutal story than its predecessor (which had its share of violence). Where Ship Breaker’s story arc was one of escape from a dead end life to a world of greater possibility (with much danger and hardship along the way), The Drowned Cities is a descent into the heart of darkness by its young protagonists. Hopefully, adults won’t be put off by the YA categorization. Though it lacks the narrative complexity of The Windup Girl, admirers of that novel are likely to find much to admire in this one.

Though the novel can be enjoyed strictly on the basis of Bacigalupi’s fluid prose and exciting story, a strong political subtext adds greatly to the interest for readers inclined to examine it. The future of America envisioned in the novel can be traced directly back to world we currently find ourselves in, and The Drowned Cities is firmly in the tradition of the dystopia as cautionary tale. But Bacigalupi avoids the traps of didacticism and preachiness by letting the setting and circumstances speak for themselves. Readers uninterested in this aspect of the book are still in for an exciting ride, but it is the ability to combine environmental, political and economic extrapolation with engaging storytelling and characterization that puts Bacigalupi’s work in the top rank of today’s science fiction. Readers of Bacigalupi’s other work will be familiar with the environmental aspects, but in The Drowned Cities he shows increasing concern with the political antecedents of his future America.

In this future, the country has been inundated by the effects of climate change. The southeast has devolved to a standard of living comparable to today’s undeveloped world as the result of coastal flooding, resource scarcity, and economic and political collapse. What’s left of the economy is based on scavenging resources for recycling, along with providing for only the most basic needs. The northeast is more functional, with “Seascape Boston” and “Manhattan Orleans” referred to as places the novels’ characters would like to escape to, although we haven’t yet seen what these areas are like. The northerners have created an army of augments to patrol the southern border in order to prevent the chaos, violence, and poverty of the south from spreading any further in their direction. These areas, as well as China, are home to powerful corporations that profit from recycling the salvage collected in the south, paying for safe passage through the war zones by trading weapons and ammunition to the local warlords.

Bacigalupi’s critique of America’s political direction goes beyond the inability to take steps to curb climate change. It is clear that the future plight he describes also relates to other aspects of current politics. China’s avoidance of devastation is telling, and can be extrapolated from the fact that China is currently being much more aggressive in pursuing alternative energy technologies to deal with a post-peak oil future than is the U.S., which is falling behind in investment in scientific education and research. China has responded to warming temperatures with massive investments in solar power technology, while in the U.S., politicians pray for rain. As a result, in the future of The Drowned Cities, China has the resources and political will to send peacekeeping forces to America, hoping to improve the situation there. Ironically, the Chinese effort to help is met with about as much enthusiasm among the native population as recent U.S. efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Bacigalupi’s critique of America’s political direction goes beyond the inability to take steps to curb climate change. It is clear that the future plight he describes also relates to other aspects of current politics. China’s avoidance of devastation is telling, and can be extrapolated from the fact that China is currently being much more aggressive in pursuing alternative energy technologies to deal with a post-peak oil future than is the U.S., which is falling behind in investment in scientific education and research. China has responded to warming temperatures with massive investments in solar power technology, while in the U.S., politicians pray for rain. As a result, in the future of The Drowned Cities, China has the resources and political will to send peacekeeping forces to America, hoping to improve the situation there. Ironically, the Chinese effort to help is met with about as much enthusiasm among the native population as recent U.S. efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

What we learn about the history of the conflict in the Drowned Cities also comments on current U.S. political conditions. Along with the United Patriot Front, additional factions include the Army of God and the Freedom Militia, among others. While there is little difference in their tactics and goals–they all claim to want to kill the traitors (any factions other than themselves) and reunite the country–those titles all have echoes in today’s right-wing politics, where demonization of political opponents, intolerance of opposing views, and inability to compromise have become increasingly mainstream.

“The Drowned Cities hadn’t always been broken. People broke it. First they called people traitors and said they didn’t belong. Said these people were good and those people were evil, and it kept going, because people always responded, and pretty soon the place was a roaring hell because no one took responsibility for what they did, and how it would drive others to respond.”

Doctor Mahfouz explains to Mouse and Mahlia that the soldier boys are not “stupid and crazy,” as they assume, but are convinced by their ideals, and are fighting merely “to destroy their enemies.” “’But they call each other traitors,’ Mouse had said. ‘Indeed. It’s a long tradition here. I’m sure whoever first started questioning their political opponents’ patriotism thought they were being quite clever.’” The Drowned Cities attempts to show us what happens when too many people start believing the demagogic politicians and pundits.

I’ve had people tell me that they can’t read Bacigalupi because his stories are too depressing. Typically, they are not denying the importance of the issues his stories raise. Rather, they just don’t want to think about these things, preferring not to engage with this reality, at least not while they’re relaxing with a novel. Bacigalupi is aware of this reaction, and has said that it’s a common one among adults, who tend to feel powerless or cynical when confronted with the need to take action, and so often prefer not to be reminded of the need. He began writing for young adults because they are unlikely to have this reaction, having not yet given up on the potential to change things before they turn out the way his stories describe. In that sense, such stories can be inspirational rather than depressing.

In any case, The Drowned Cities (and Ship Breaker) are not depressing. In fact, the main characters in both novels take actions to improve their own situations, and the door is opened to the potential for the stricken communities to dig themselves out of the holes they have fallen into. Mahlia is an inspiring character in her ultimate refusal to accept the irrationality of her world.

“Done with being shoved around and threatened. Done with the bargaining that always said that if she wanted to live, someone else had to die. Done with armies like the UPF and Army of God and Freedom Militia, who all claimed that they’d do right, just as soon as they were done doing wrong.”

It may be depressing to consider the implications of the future Bacigalupi shows us, but it’s even more depressing to think that we could knowingly go down that road. The hope is that, just as young science fiction fans once grew up to work in the space program, wanting to achieve the space-going future they read about in the ‘40s and ‘50s, today’s young readers will be inspired to begin the work on the political and economic changes that could help us avoid the future seen in these novels. It’s certainly possible, if we can face the facts and work together. We may have to postpone space travel for a while (though I’m not willing to give up yet), but clipper ships powered by solar kite sails are pretty cool, too.

GMRC Review: Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including several for the GMRC. Be sure to check out Scott’s excellent blog series Forays into Fantasy too!

Childhood’s End never won an award, but the Hugo wasn’t awarded for 1954, and there were no other science fiction awards at the time. It does, however, show up on the biggest "best of" lists included on Worlds Without End for which it would be eligible (except the ISFDB 100, surprisingly). It continues to be considered a classic nearly six decades after its initial publication as a Ballantine paperback. I recall it from my teenage years as being considered, pretty much by acclimation of science fiction fans and professionals, one of the best and most important SF novels, and I agreed at the time. It was voted the eighth best SF novel of all time in the 1998 Locus Best SF Novels of All-Time poll. There’s always a danger revisiting SF this old—predictions have been proved wrong, writing styles tended to be less engaging, cultural influences from the writers’ own background lead to anachronistic attitudes among characters. So, how does Childhood’s End hold up? Will it continue to be pointed to as a classic of the field?

Childhood’s End never won an award, but the Hugo wasn’t awarded for 1954, and there were no other science fiction awards at the time. It does, however, show up on the biggest "best of" lists included on Worlds Without End for which it would be eligible (except the ISFDB 100, surprisingly). It continues to be considered a classic nearly six decades after its initial publication as a Ballantine paperback. I recall it from my teenage years as being considered, pretty much by acclimation of science fiction fans and professionals, one of the best and most important SF novels, and I agreed at the time. It was voted the eighth best SF novel of all time in the 1998 Locus Best SF Novels of All-Time poll. There’s always a danger revisiting SF this old—predictions have been proved wrong, writing styles tended to be less engaging, cultural influences from the writers’ own background lead to anachronistic attitudes among characters. So, how does Childhood’s End hold up? Will it continue to be pointed to as a classic of the field?

I suspect the answer to that last question will be "yes" for a long time to come. Sure, there are a few details that stick out as dating the novel. As in all ’50s (and quite a bit of later) science fiction, calculating and problem-solving computers are predicted, but not digital data storage and instant access to information. Despite extreme technological advances, people still use paper and photographic film. There is some reflexive sexism—sexual freedom and attitudes improve, but women still seem to be tied to their reproductive roles, while men are the "thinkers and doers." These details are noticeable, especially considering that Clarke is describing a future technological and social utopia, but they are very much in the background, and thus easy to ignore, since the novel’s themes and ideas are not much concerned with them.

Arthur C. Clarke‘s prose is little more than serviceable, but it does open up at times when describing the wondrousness of alien worlds, vistas of incomprehensible scale, or the sublimity of humanity’s evolution in the concluding section.

"Through the clash and tug of conflicting gravitational fields the planet travelled along the loops and curves of its inconceivably complex orbit, never retracing the same path. Every moment was unique; the configuration which the six suns now held in the heavens would not repeat itself this side of eternity. An even here there was life. Though the planet might be scorched by the central fires in one age, and frozen in the outer reaches in another, it was yet the home of intelligence. The great, many-faceted crystals stood grouped in intricate geometrical patterns, motionless in the eras of cold, growing slowly along the veins of mineral when the world was warm again. No matter if it took a thousand years for them to complete a thought. The universe was still young, and Time stretched endlessly before them…"

Such descriptions are especially attention-getting when contrasted with the straightforward prose more typical of the novel.

Characterization is minimal, as each major section of the novel introduces a few characters to play important roles or represent prevalent attitudes necessary to move the story forward. But these characters perform these roles well, and seem believable enough. In fact, given the nature of the story, I was expecting much less characterization in the usual sense, since no individual can have much "stage time" in a novel of around two-hundred fifty pages that covers a couple of centuries of human history. And the most important character in Childhood’s End is the human race itself, a point that becomes increasingly clear as the novel progress. It is humanity’s potential for "character development" that is at the heart of the book. Clarke is interested in the potential for human development. His ideas could have been presented in non-fiction form, but he chose to do so in the form of a novel. It could easily not have worked. The fact that it is able to present such big ideas, and still work well as a novel, is impressive.

Clarke seems to be commonly thought of as a writer more interested in technology than characters—the alien ship in Rendezvous with Rama; the space elevator in Fountains of Paradise—but the future depicted in Childhood’s End is not mainly technological. Rather, it is a step in human evolution, preceded by a social utopia (with a little help from some aliens).

The space race is proceeding, and humanity seems on the brink of war, when the Overlords arrive on Earth. Speaking through a single representative "supervisor"—Karellen, the only character to be involved in every stage of the story—the alien Overlords impose utopia on the human race. How would we respond to a truly benevolent occupation? Would we be angry that we could no longer fight wars, even if our conquerors also removed any possible reason for conflict? Technically, humanity was not entirely free, but individual freedom was not interfered with as long as no one harmed anyone else. And all material needs are met, so there is nothing to fight over. Empires often believe that they are improving the lives of those whom they conquer, and such attitudes are justifiably criticized. What if the conquerors are right?

Some object (especially on religious grounds) to the loss of freedom, but humanity soon settles gratefully into a "Golden Age."

"By the standards of all earlier ages, it was Utopia. Ignorance, disease, poverty and fear had virtually ceased to exist. The memory of war was fading into the past as a nightmare vanishes with the dawn; soon it would lie outside the experience of all living men. With the energies of mankind directed into constructive channels, the face of the world had been remade."

Production is largely automated, and resources previously used for war and defense are made available for construction and consumption. Crime is practically eliminated, since there is no poverty, and the Overlords can maintain complete surveillance over the planet. Leisure is greatly increased, psychological problems fall away, and rationality prevails. People can easily travel to wherever they want and live wherever they like (flying cars!). "It was a completely secular age… The creeds that had been based upon miracles and revelations had collapsed utterly." I find this sort of speculation fascinating, and I’m sure it’s a big part of the appeal of the novel, especially to younger readers. Would it really play out this way? It’s a hopeful thought, and does not seem impossible, given the circumstances. What if the world ran on truly rational principles? That is the question posed by the "tyranny" of the Overlords. But the sticky question of freedom remains. It is still not a perfect world, and nagging questions remain. What comes next for humanity, when there seems nothing to strive for? Why have the Overlords forbidden space exploration? What is their real motivation?

Production is largely automated, and resources previously used for war and defense are made available for construction and consumption. Crime is practically eliminated, since there is no poverty, and the Overlords can maintain complete surveillance over the planet. Leisure is greatly increased, psychological problems fall away, and rationality prevails. People can easily travel to wherever they want and live wherever they like (flying cars!). "It was a completely secular age… The creeds that had been based upon miracles and revelations had collapsed utterly." I find this sort of speculation fascinating, and I’m sure it’s a big part of the appeal of the novel, especially to younger readers. Would it really play out this way? It’s a hopeful thought, and does not seem impossible, given the circumstances. What if the world ran on truly rational principles? That is the question posed by the "tyranny" of the Overlords. But the sticky question of freedom remains. It is still not a perfect world, and nagging questions remain. What comes next for humanity, when there seems nothing to strive for? Why have the Overlords forbidden space exploration? What is their real motivation?

That last issue is addressed in the concluding part of the novel. The achievement of Utopia is not childhood’s end, but a final step in the fostering of the ultimate evolution to adulthood. It involves Clarke’s interpretation of the possible meaning of mysticism and psychic phenomena, the existence of a universal "Overmind," and the meaning of the Overlords’ task. Utopia will be left behind for a future humanity cannot yet comprehend. I’m tempted to quote some of the passages describing this, as they are among the best in the book, but suffice it to say that the final chapter of Childhood’s End remains one of the most gripping in all of science fiction.

Considering humanity itself as the main character of Childhood’s End, "characterization" is actually Clarke’s major strength in this novel. We follow the character from childhood to maturity—from an existence overly determined by emotion and impulse, to one governed by rationality, to "the end of Man… an end that repudiated both optimism and pessimism alike." I questioned the journey much of the way, as my cynical attitude wanted to intrude. I kept looking for the fatal flaw in Clarke’s arguments. It remains thought-provoking. About halfway through the novel, I gave up looking for narrative or philosophical flaws, and considered the possibilities…

Forays into Fantasy: The Castle of Otranto, the Gothic Novel and the Origins of Fantasy

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

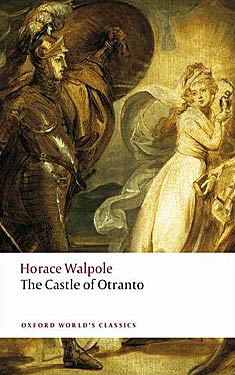

As my interest in science fiction was revived over the last couple of years, and I decided to expand my reading into fantasy as well, I went in search of context. Looking for a guide to some superior and important examples of fantasy, beyond the usual suspects, I pulled David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels off the shelf (and examples of some of these novels will continue to show up in this series of posts), but Pringle begins in 1946, and I wanted to start at the beginning. Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, published in 1988, starts in the eighteenth century. Specifically, the first book listed is Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) — no surprise there. The other three examples from the 1700s, though, I had never heard of before: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, Vathek by William Beckford, and The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis. Upon reading Cawthorn and Moorcock’s essays, it became clear that these were all examples of early Gothic novels, which make up one of the earliest strands of the fantasy genre.

As my interest in science fiction was revived over the last couple of years, and I decided to expand my reading into fantasy as well, I went in search of context. Looking for a guide to some superior and important examples of fantasy, beyond the usual suspects, I pulled David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels off the shelf (and examples of some of these novels will continue to show up in this series of posts), but Pringle begins in 1946, and I wanted to start at the beginning. Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, published in 1988, starts in the eighteenth century. Specifically, the first book listed is Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) — no surprise there. The other three examples from the 1700s, though, I had never heard of before: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, Vathek by William Beckford, and The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis. Upon reading Cawthorn and Moorcock’s essays, it became clear that these were all examples of early Gothic novels, which make up one of the earliest strands of the fantasy genre.

So, did fantasy as a genre really begin in the 1700s (clearly, there was fantastic literature prior to that), and what role did these Gothic novels play in those beginnings? During this eighteenth century, poets and philosophers debated the nature of imagination, and there was a new and rising view that the imagination was not merely a repository of memory and observation, but was a faculty capable of the visionary illumination of the unknown, as Samuel Coleridge and William Blake tried to do in their poetry. In literature, these ideas led to the ongoing distinction between the realistic and the fantastic. As Gary K. Wolfe writes in “Fantasy from Dryden to Dunsany,” in The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature (2012):

“The modern fantasy novel, and to an arguable extent the modern novel itself, is in part an outgrowth of this debate. While we can reasonably argue that the fantastic in the broadest sense had been a dominant characteristic of most world literature for centuries prior to the rise of the novel, we can also begin to discern that the fantasy genre may well have had its origins in these eighteenth- and nineteenth-century discussions of fancy vs. imagination, history vs. romance…”

In particular, Wolfe sees the fantasy genre as arising from three sources during the 1700s and 1800s: “private history” novels such as Robinson Crusoe, a revival of interest in old folk tales and fairy tales, and the vogue for Gothic novels, all three of which required the use of imagination to envision what we now think of as “the fantastic.”

Where, then, did this Gothic strand of literature arise from, and what does it entail? Our story begins during the latter stages of the Roman Empire, when the Goths pillaged their way south from Scandinavia, ultimately sacking Rome in 410. After gaining control of the Italian peninsula, they eventually lost power later in the Middle Ages, after sundry violent run-ins with the Huns, the Franks, and the Moors. Due to its association with the decline of the Classical world, the term “Gothic” came into use during the 1500s as a pejorative term for a medieval style in art and architecture, from the twelfth — through the sixteenth — centuries, which was considered during the Renaissance to be ugly and barbaric when compared to the Classical art and architecture it supplanted. It is best represented by the intricate and sculpturally adorned Medieval cathedrals with their soaring pointed arches, which took advantage of advances in structural design to achieve previously unprecedented height, with correspondingly tall windows and, of course, lots of gargoyles.

Where, then, did this Gothic strand of literature arise from, and what does it entail? Our story begins during the latter stages of the Roman Empire, when the Goths pillaged their way south from Scandinavia, ultimately sacking Rome in 410. After gaining control of the Italian peninsula, they eventually lost power later in the Middle Ages, after sundry violent run-ins with the Huns, the Franks, and the Moors. Due to its association with the decline of the Classical world, the term “Gothic” came into use during the 1500s as a pejorative term for a medieval style in art and architecture, from the twelfth — through the sixteenth — centuries, which was considered during the Renaissance to be ugly and barbaric when compared to the Classical art and architecture it supplanted. It is best represented by the intricate and sculpturally adorned Medieval cathedrals with their soaring pointed arches, which took advantage of advances in structural design to achieve previously unprecedented height, with correspondingly tall windows and, of course, lots of gargoyles.

As pointed out by Adam Roberts in his essay on “Gothic and Horror Fiction” also in The Cambridge Companion, by the time the term “Gothic” was first used to describe a form of literature, in the mid-eighteenth century, its “primary signification… was that of barbarous anti-enlightenment.” At the same time, a revival of interest in Gothic aesthetics would result in the term becoming more complimentary in the eyes of those who began to bring the now old-fashioned medieval styles back into fashion. Among these was Horace Walpole, who rebuilt his London mansion in what he considered to be a “Gothic” style, and wrote what is generally agreed to be the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto: A Story, published in 1764. (Subsequent editions would be subtitled A Gothic Story.)

Walpole originally published The Castle of Otranto under a pseudonym, claiming in the preface that it was a translation of a recently discovered manuscript printed in 1529 and most likely written between 1095 and 1243, thus pretending to establish it as an actual work of the Middle Ages. He speculates that it was written by a priest in order to “avail himself of his abilities as an author to confirm the populace in their ancient errors and superstitions” at a time when such superstitions were being challenged by the Italian intelligentsia. Although presented by the translator as a mere entertainment:

“Some apology for it is necessary. Miracles, visions, necromancy, dreams, and other preternatural events, are exploded now even from romances. That was not the case when our author wrote; much less when the story itself is supposed to have happened. Belief in every kind of prodigy was so established in those dark ages, that an author would not be faithful to the manners of the times, who should omit all mention of them. He is not bound to believe them himself, but he must represent his actors as believing them. If this air of the miraculous is excused, the reader will find nothing else unworthy of his perusal. Allow the possibility of the facts, and all the actors comport themselves as persons would do in their situation… Terror, the author’s principal engine, prevents the story from ever languishing; and it is so often contrasted by pity, that the mind is kept up in a constant vicissitude of interesting passions.”

Clearly, Walpole was aware of the debate over the role of imagination in literature described above by Wolfe, and was attempting to combine the virtues of the modern novel with the fanciful content of ancient stories and myths. Ironically, while claiming to apologize to the reader for the old-fashioned fantastical elements in the story, what Walpole was really doing, by bringing these elements into a novel, was to create something entirely new. In the Middle Ages, people really were superstitious, and such stories would not have been considered “fantastic” in the modern sense. By the 1700s, by which time the Enlightenment had banished superstition from the educated mind, bringing back the fantastic required a new use of imagination for both writers and their audience.

Clearly, people were ready for it. In a popular and commercial sense, his experiment was very successful, unleashing a sea of imitators. Despite Walpole’s apology for it, it is that very “air of the miraculous” that makes the novel intriguing. The plot itself is quite ludicrous, but individual incidents, and the overall mood, keep things interesting. Manfred, lord of the Castle of Otranto, while overseeing the wedding of his sickly son Conrad to Isabella, is shocked and dismayed when a giant helmet appears and crushes Conrad to death, leaving Manfred without an heir. The enormous helmet is otherwise identical to that once worn by Alfonso the Good, who is supposed to have granted the castle to Manfred’s grandfather many years before. Clearly concerned about the implications of this strange event, and determined to maintain his family’s succession, he announces his intention to divorce his wife Hippolita, who has been incapable of providing him with another son, and marry Isabella himself. Neither woman is pleased. Isabella escapes with the help of Theodore, whom Manfred sentences to death. Chasing Theodore and Isabella into the vaults beneath the castle, Manfred encounters an apparition of his grandfather, as well as manifestations of giant armored body parts and weapons, presumably arising from the same source as the helmet. As Manfred had feared, these visions herald the fulfillment of a prophecy that foretold the end of his family’s usurpation of the castle, and the return of its rightful heir, who turns out to be Theodore. Isabella ends up Queen of the castle after all.

Clearly, people were ready for it. In a popular and commercial sense, his experiment was very successful, unleashing a sea of imitators. Despite Walpole’s apology for it, it is that very “air of the miraculous” that makes the novel intriguing. The plot itself is quite ludicrous, but individual incidents, and the overall mood, keep things interesting. Manfred, lord of the Castle of Otranto, while overseeing the wedding of his sickly son Conrad to Isabella, is shocked and dismayed when a giant helmet appears and crushes Conrad to death, leaving Manfred without an heir. The enormous helmet is otherwise identical to that once worn by Alfonso the Good, who is supposed to have granted the castle to Manfred’s grandfather many years before. Clearly concerned about the implications of this strange event, and determined to maintain his family’s succession, he announces his intention to divorce his wife Hippolita, who has been incapable of providing him with another son, and marry Isabella himself. Neither woman is pleased. Isabella escapes with the help of Theodore, whom Manfred sentences to death. Chasing Theodore and Isabella into the vaults beneath the castle, Manfred encounters an apparition of his grandfather, as well as manifestations of giant armored body parts and weapons, presumably arising from the same source as the helmet. As Manfred had feared, these visions herald the fulfillment of a prophecy that foretold the end of his family’s usurpation of the castle, and the return of its rightful heir, who turns out to be Theodore. Isabella ends up Queen of the castle after all.

The genre ushered in by Walpole’s story remained very popular until about 1820, and continued to evolve thereafter (think of Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights, Dracula, and Rebecca). Very few of the novels from the original flowering of the Gothic are still read, but they represented an unleashing of imaginative literature that would ultimately lead to the development of the modern genres of horror (which still maintains an explicitly gothic strand), fantasy, and even science fiction, whose readers are often looking for the same “sense of wonder” as was the original audience for gothic fiction.

The characteristic feeling evoked by the Gothic story is the combination of the familiar and the foreign — the simultaneous attraction and repulsion that Freud wrote about as “the uncanny.” This characteristic of the Gothic has to do with the mood rather than the well-known trappings of the stories — the feeling of mysteriousness, that there are things happening that we can’t quite understand and that may ultimately remain obscure; that important realizations are just out of reach in the shadows and gloom. The reader wants to find out what horrors (usually evils from the past returning to haunt the present) underlie the events in the story, but at the same time is afraid to find out.

The typical elements of the settings in which these strange stories play out have become iconic. As Adam Roberts explains:

“In Otranto we find, in nascent form, many of the props and conventions that were to reappear in the scores of novels published at the height of the Gothic vogue…: moody atmospherics, picturesque and sublime scenery, darkness, buried crimes (especially murderous and incestuous crimes) revealed, and most of all a spectral supernatural focus. Many imitators tried to follow Walpole’s commercial success by littering their novels with similar props, settings and conventions — the haunted castle, the night-time graveyard, the Byronic villain and so on,”

But the elements that make the works successful are not these outward trappings, but rather their ability to invoke the uncanny and the transgressive, and to fire the reader’s imagination.

But the elements that make the works successful are not these outward trappings, but rather their ability to invoke the uncanny and the transgressive, and to fire the reader’s imagination.

As for Otranto in particular, it is the first, but not the very best. Fantasy readers today will have no problem with the fantastic elements, but may struggle with the improbable plot twists, many of which hinge on mistaken or hidden identity, and with the overwrought dialogue. Those willing to make allowances, however, will be carried along by the onrushing events and the feverish intensity of the characters’ emotions and actions, until the situation they are caught up in is finally resolved. These events, manifested through supernatural interventions into the real world, were precipitated by past injustice, a pattern which will play out again in subsequent Gothic novels, often within some variation on Walpole’s shadowy castle and subterranean vaults, literary images that have never ceased to haunt readers of the fantastic.

Next: More early Gothic novels will be reviewed in a future post, but up next is a 1949 American fantasy novel set in a land where stories are real: Silverlock by John Myers Myers.

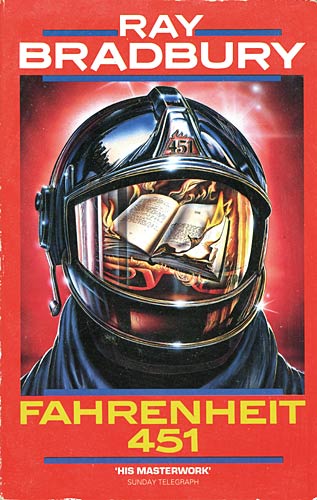

GMRC Review: Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including this latest review for the GMRC.

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for a good list of books. He found David Pringle’s Best 100 Science Fiction Novels list to his liking and is currently working his way through the list. He has posted a bunch of reviews for WWEnd including this latest review for the GMRC.

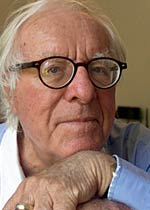

Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man and Fahrenheit 451 are two of the earliest SF books I remember reading, around age ten, probably because they were the only science fiction books on my parents’ shelves. Bradbury, then, and Asimov a little later, would be my “gateway drugs” into the genre, and I read everything I could find in the library by both authors at a young age. I remember liking both books, but preferring The Illustrated Man collection, and rereading Fahrenheit 451 today, I have to agree with my ten-year-old self that Bradbury is much better at shorter lengths. Not that Fahrenheit is very long—for a novel, it’s extremely short—but that only makes the limitation more obvious. A simple theme that works well as the basis of a short story can outstay its welcome in a novel, especially if the author fails to engage with the ambiguities and subtleties inherent in it. Much as I was looking forward to rereading this, I ended up surprisingly disappointed. What seemed profound and meaningful to me as a child, now comes across as a problematic and unsubtle screed about the dangers of conformity and mass media. The idea that “the majority,” if given its way, would stamp out individualism, seems unrealistic, and reads now like an unconvincing condemnation of communism. This is prime period Bradbury, however, so my arguments with the novel are often overcome by his striking images and the fascinating strangeness of the world he creates. (Spoilers follow, in case anyone hasn’t read this novel yet!)

Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man and Fahrenheit 451 are two of the earliest SF books I remember reading, around age ten, probably because they were the only science fiction books on my parents’ shelves. Bradbury, then, and Asimov a little later, would be my “gateway drugs” into the genre, and I read everything I could find in the library by both authors at a young age. I remember liking both books, but preferring The Illustrated Man collection, and rereading Fahrenheit 451 today, I have to agree with my ten-year-old self that Bradbury is much better at shorter lengths. Not that Fahrenheit is very long—for a novel, it’s extremely short—but that only makes the limitation more obvious. A simple theme that works well as the basis of a short story can outstay its welcome in a novel, especially if the author fails to engage with the ambiguities and subtleties inherent in it. Much as I was looking forward to rereading this, I ended up surprisingly disappointed. What seemed profound and meaningful to me as a child, now comes across as a problematic and unsubtle screed about the dangers of conformity and mass media. The idea that “the majority,” if given its way, would stamp out individualism, seems unrealistic, and reads now like an unconvincing condemnation of communism. This is prime period Bradbury, however, so my arguments with the novel are often overcome by his striking images and the fascinating strangeness of the world he creates. (Spoilers follow, in case anyone hasn’t read this novel yet!)