GMRC Review: A for Anything by Damon Knight

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s seventh GMRC review to feature in our blog.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s seventh GMRC review to feature in our blog.

Since January, I have read a novel a month by one of the winners of the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award, given by the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America. I thought I was about time to read a novel by the man himself. (Knight won the award in 1994. He was a founder of the SFWA and the award was named for him after his death in 2002.) Although several of the Grand Masters I have read I have been reading for the first time this year, Knight is perhaps the one I knew the least about. I would be hard pressed to name any of his books. Even though I worked around used books for thirty years, I cannot picture any of his covers or remember that he ever merited his own shelf. Somewhere along the way I picked up the fact that he wrote the short story “To Serve Man,” which became a classic Twilight Zone episode. (Don’t get on that ship! The book… the book… it’s a cookbook!) And so I picked up A for Anything with no expectations.

Since January, I have read a novel a month by one of the winners of the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award, given by the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America. I thought I was about time to read a novel by the man himself. (Knight won the award in 1994. He was a founder of the SFWA and the award was named for him after his death in 2002.) Although several of the Grand Masters I have read I have been reading for the first time this year, Knight is perhaps the one I knew the least about. I would be hard pressed to name any of his books. Even though I worked around used books for thirty years, I cannot picture any of his covers or remember that he ever merited his own shelf. Somewhere along the way I picked up the fact that he wrote the short story “To Serve Man,” which became a classic Twilight Zone episode. (Don’t get on that ship! The book… the book… it’s a cookbook!) And so I picked up A for Anything with no expectations.

Perhaps I should not have read his first novel, although I am inclined to start at the first with an author. But I have to say this is the most peculiar book I have read in some time, and not in a particularly good way. Here’s what happens in the first three chapters.

GMRC Review: Starship Troopers by Robert A. Heinlein

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s sixth GMRC review to feature in our blog.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s sixth GMRC review to feature in our blog.

My Junior high school library had a copy of Starship Troopers on the shelf. I never read it. I had read some of the Robert Heinlein juveniles, and I think I assumed Troopers was another. I had also read a paperback copy of The Puppet Masters, which was one of my first forays into genuinely adult SF and of course I loved it. But I loved monsters more than military, and so Troopers never caught my attention although I loved that first quote, “Come on, you apes. You want to live forever?”

My Junior high school library had a copy of Starship Troopers on the shelf. I never read it. I had read some of the Robert Heinlein juveniles, and I think I assumed Troopers was another. I had also read a paperback copy of The Puppet Masters, which was one of my first forays into genuinely adult SF and of course I loved it. But I loved monsters more than military, and so Troopers never caught my attention although I loved that first quote, “Come on, you apes. You want to live forever?”

Soon I quit reading science fiction in general and I got the word that Heinlein was the bully pulpit for the military establishment. Boo. Hiss. So I was was surprised that the novel was not nearly so jingoistic as I expected. I think it would have defeated me, however, in seventh grade. Despite the good action and cool bugs, that middle section of officer training school would have done me in.

A couple of reviews I read emphasized that the novel should not be confused with what the reviewers obviously considered the vastly inferior Paul Verhoeven 1997 film version. These reviewers must be the true believers. I loved the movie when I first saw it and thoroughly enjoyed it watching it again after reading the novel the other day. Verhoeven passes Heinlein’s text through the deconstructionist mill. (Did Michel Foucault get a consulting credit?) I’ve already said the novel did not strike me as the jingoistic broadside I anticipated, but what fun to see these minor celebrities giving their severely limited all to this high-gloss parody of everything Heinlein must have held dear. There is a rumor that the actors, few of whom were the sharpest pencils in the studio box, had no idea they were being made fun of. I think that like most young actors with few credits to their names they were more interested in their paychecks than in the socio-political implications of their characters.

A couple of reviews I read emphasized that the novel should not be confused with what the reviewers obviously considered the vastly inferior Paul Verhoeven 1997 film version. These reviewers must be the true believers. I loved the movie when I first saw it and thoroughly enjoyed it watching it again after reading the novel the other day. Verhoeven passes Heinlein’s text through the deconstructionist mill. (Did Michel Foucault get a consulting credit?) I’ve already said the novel did not strike me as the jingoistic broadside I anticipated, but what fun to see these minor celebrities giving their severely limited all to this high-gloss parody of everything Heinlein must have held dear. There is a rumor that the actors, few of whom were the sharpest pencils in the studio box, had no idea they were being made fun of. I think that like most young actors with few credits to their names they were more interested in their paychecks than in the socio-political implications of their characters.

Book and film should absolutely be absorbed as a single experience. Probably the book should be read first, just so you do not have to picture Casper Van Diehm in the leading role until the last possible moment.

The Horror! The Horror! Joe McKinney

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. In this series Dee explores the darker side of genre fiction and it’s practitioners. Be sure to visit his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com for more genre goodness.

For an author of zombie novels, Joe McKinney has an unbeatable backstory. For the past twenty years or so, he has been a policeman in San Antonio, Texas, serving as a homicide detective, then in the office of emergency preparedness, and now overseeing the 911 division. It’s not that San Antonio has been especially prone to zombie attacks during that time, but cops have seen a lot of the worst parts of human nature. McKinney’s protagonists, who tend to be cops themselves, cannot possibly be prepared for the horrific situations they encounter, but they handle themselves cooly and professionally – at least for as long as such a response is possible. If I found myself in a zombie-infested quagmire, I would want to stay close to one of McKinney’s main characters, unless he proved to be one of the immoral bastards the author also throws into the mix.

For an author of zombie novels, Joe McKinney has an unbeatable backstory. For the past twenty years or so, he has been a policeman in San Antonio, Texas, serving as a homicide detective, then in the office of emergency preparedness, and now overseeing the 911 division. It’s not that San Antonio has been especially prone to zombie attacks during that time, but cops have seen a lot of the worst parts of human nature. McKinney’s protagonists, who tend to be cops themselves, cannot possibly be prepared for the horrific situations they encounter, but they handle themselves cooly and professionally – at least for as long as such a response is possible. If I found myself in a zombie-infested quagmire, I would want to stay close to one of McKinney’s main characters, unless he proved to be one of the immoral bastards the author also throws into the mix.

McKinney’s Dead World series consists of Dead City, Apocalypse of the Damned, and Flesh Eaters. In September, 2012, this trilogy will be joined by Mutated. McKinney’s titles let you know what you are getting. His initial trilogy has an interesting chronology. Dead City (2006) takes place in San Antonio during the night that the infection plaguing a storm-ravaged Houston first makes its way north. There are those inevitable early police reports: “We got a party getting out of hand down on the east side.” Apocalypse (2010) returns to Houston, a month or so after the city has been quarantined. Only if you have never watched a horror movie in your life, you know how well that quarantine is going to hold. The novel follows a band of escapees heading north to a settlement that promises protection for the zombie hordes. Again, unless you have never watched a horror movie in your life, you know how well that is going to work out.

The problem endemic to zombie fiction, on which the floodgates have now officially been opened, is that we have, after all, seen all this before. George Romero created Night of the Living Dead in 1968. To some extent, all zombie films and fiction are a gloss on the Romero original. (I am not counting earlier zombie works that based themselves on Haitian and voodoo motifs.) Something brings the dead back to life. The deadly extraterrestrial rays of forty years ago have been for the most part updated to hemorrhagic viruses. The infection spreads by bites or bodily fluids, victims crave human flesh, and there is no cure. The only real question that each author and filmmaker must decide is whether to create fast or slow zombies. I am in the slow zombie camp myself, but I admire McKinney’s solution. He allows for relative mobility based on the age and health of the victim.

McKinney’s prose has the no-nonsense, laconic rhythm that fits well with his police officer protagonists. The stories are predictable, but the secret here is to make each moment believable and to pace the gross outs with realistic depictions of what it is going to take for each character to live through the next hour. McKinney’s novels were getting noticed by those who give horror writing awards early on, and in 2011 he won a Bram Stocker Award for Flesh Eaters. And that third outing is definitely where he came into his own as a writer. Dead City was just like a zombie movie, except it took five hours to read instead of ninety minutes to watch. Apocalpyse succeeded in opening up the story, but the climax came directly from accounts of the Jonestown Massacre, only with zombies instead of federal agents on hand for the tragic conclusion.

Flesh Eaters goes back to Houston and the series of storms that not only destroy the city but through chemical spills and god knows what else sets in motion the infections that will change life on earth forever. Again, this is a zombie story, and so we know basically what is going to happen. But for the first time, McKinney creates morally complex characters capable of both courage and betrayal in the face of the unthinkable horrors they confront.

I am not going to become a fan of zombie fiction. The only other example I have read was the well-received novel Feed by Mira Grant and I absolutely hated it. But come September, I feel certain that I will be searching out McKinney’s latest, even though with the title Mutated I am pretty damn sure I now at least three fourths of what is going to happen.

You can read my reviews of Dead City, Apocalypse of the Damned, Flesh Eaters and Feed right here on Worlds Without End.

GMRC Review: The Big Time by Fritz Leiber

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s fifth GMRC review to feature in our blog.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s fifth GMRC review to feature in our blog.

The universe is at war. Leiber’s short novel is set, on one level, in the later part of the 20th century, but it seems that war has been going of forever. Here is how Greta Forzane, our narrator, states things.

The universe is at war. Leiber’s short novel is set, on one level, in the later part of the 20th century, but it seems that war has been going of forever. Here is how Greta Forzane, our narrator, states things.

“This war is the Change War, a war of time travelers – in fact, our private name for being in the war is being on the Big Time. Our soldiers fight by going back to change the past, or even ahead to change the future, in ways to help our side win the final victory a billion years or more from now. A long, killing business, believe me.”

Greta is an entertainer at The Place, a self-enclosed environment outside space and time. Solders fresh from battle follow the change winds and arrive for medical assistance and some R&R. Picture a USO with freer alcohol and relaxed sexual attitudes. Advanced technology provides state-of-the art medical treatment and sex partners to suit every fancy. If a visiting soldier does not take to one of the on-staff entertainers, or if his alien anatomy causes complications, he can always choose from the hundreds of ghost girls kept folded into envelopes in the storage area. (It would slow things down at this point to attempt an explanation of ghost girls.)

Life at The Place doesn’t seem all that bad, although it could get a bit boring since it goes on more or less forever. But those who run the place see old friends returning from battle on a regular basis, and they stay occupied with their own intrigues and affairs. They have only to wait for their maintainer, the device that keeps The Place intact outside of space and time, to start flashing its blue lights. That’s the sign that the change door is about to open and new arrivals or possibly old friends will come crashing through.

The Horror! The Horror! – Tom Piccirilli

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. In this series Dee explores the darker side of genre fiction and it’s practitioners. Be sure to visit his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com for more genre goodness.

The less Tom Piccirilli encumbers his novels with plot, the better they are. At least that has been the case in his five early horror novels I have read: Hexes (1999), The Deceased (2000), The Night Class (2001), A Choir of Ill Children (2004) and, Headstone City (2006). The novels are by no means short of grotesque and often unpleasant incidents. But Piccirilli works by accumulation not by character arcs and interwoven themes. His theme is consistently that of a young man, in his late twenties or thirties, who must come to accept his role in society, whether it is the gangland of Brooklyn or a backwater town somewhere in the American South. But the novels are not traditional bildungsromans. This is not in the world of David Copperfield or Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship. These are nightmares.

The less Tom Piccirilli encumbers his novels with plot, the better they are. At least that has been the case in his five early horror novels I have read: Hexes (1999), The Deceased (2000), The Night Class (2001), A Choir of Ill Children (2004) and, Headstone City (2006). The novels are by no means short of grotesque and often unpleasant incidents. But Piccirilli works by accumulation not by character arcs and interwoven themes. His theme is consistently that of a young man, in his late twenties or thirties, who must come to accept his role in society, whether it is the gangland of Brooklyn or a backwater town somewhere in the American South. But the novels are not traditional bildungsromans. This is not in the world of David Copperfield or Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship. These are nightmares.

Demonic evil, ghosts, astral projections, some handy knowledge of witchcraft, and alternate realities are daily issues for Piccirilli’s protagonists. In Headstone City, Johnny Danetello endures frequent visitations from the dead, ranging from the girl he could not save from an overdose to his mother to "the boy with the damaged head." Caleb Prentiss, an alcoholic upperclassman at a small, snowbound Midwestern university, wants to find out more about the girl murdered in his dorm room over winter break. He is often accompanied by his sister who committed suicide; and, when he receives the unasked-for blessing of the stigmata in both palms, he leaves bloody paths across the snowy campus. Thomas, the central character of A Choir of Ill Children has too many issues to go into here, but one involves the care of his brothers, triplets conjoined at the frontal lobe.

Demonic evil, ghosts, astral projections, some handy knowledge of witchcraft, and alternate realities are daily issues for Piccirilli’s protagonists. In Headstone City, Johnny Danetello endures frequent visitations from the dead, ranging from the girl he could not save from an overdose to his mother to "the boy with the damaged head." Caleb Prentiss, an alcoholic upperclassman at a small, snowbound Midwestern university, wants to find out more about the girl murdered in his dorm room over winter break. He is often accompanied by his sister who committed suicide; and, when he receives the unasked-for blessing of the stigmata in both palms, he leaves bloody paths across the snowy campus. Thomas, the central character of A Choir of Ill Children has too many issues to go into here, but one involves the care of his brothers, triplets conjoined at the frontal lobe.

Piccirilli’s locales are sharply observed locations that could exist nowhere but in his novels. In addition to the snowbound campus in The Night Class and the swampy town of Kingdom Come in A Choir of Ill Children, Piccirilli delineates in Hexes the town of Summerfel – Summerfell! – a small town dominated by an asylum named Panecraft, a lighthouse undermined by tunnels containing some unspeakable horror, a local hangout called Krunch Burger, and a rich man’s house that is more like a castle than a mansion. If you don’t like things in Summerfel, you can always move the next town over to Gallows. Headstone City takes place in an imaginary neighborhood of an otherwise identifiable Brooklyn, a neighborhood where the decaying mansions of stars from the earliest days of silent film surround the enormous cemetery of the title. The neighborhood is still run by some goonish gangsters who have mostly moved their money into legit businesses but who still, guided by a misplaced enthusiasm for their once glorious past, enact the occasional bloody vendetta against one another.

Piccirilli’s locales are sharply observed locations that could exist nowhere but in his novels. In addition to the snowbound campus in The Night Class and the swampy town of Kingdom Come in A Choir of Ill Children, Piccirilli delineates in Hexes the town of Summerfel – Summerfell! – a small town dominated by an asylum named Panecraft, a lighthouse undermined by tunnels containing some unspeakable horror, a local hangout called Krunch Burger, and a rich man’s house that is more like a castle than a mansion. If you don’t like things in Summerfel, you can always move the next town over to Gallows. Headstone City takes place in an imaginary neighborhood of an otherwise identifiable Brooklyn, a neighborhood where the decaying mansions of stars from the earliest days of silent film surround the enormous cemetery of the title. The neighborhood is still run by some goonish gangsters who have mostly moved their money into legit businesses but who still, guided by a misplaced enthusiasm for their once glorious past, enact the occasional bloody vendetta against one another.

Several internet customer reviews complain that these books make no sense, but I think those readers are looking for the wrong things. Like a coherent plot. Piccirilli is a lot of fun to read. There is always that central character who knows a bit more than those around him; whether it is more effective magical spells or just that so much of what is going on is bullshit. When Piccirilli brings more plotting into the mix, things tend to go wrong. The Deceased turns into little more that a pretty good horror movie, with girls, who I assume have large breasts, running around an old house during a thunderstorm. The gangster story that runs through Headstone City is not as resolved or effective as the weirdness that underlies it.

Several internet customer reviews complain that these books make no sense, but I think those readers are looking for the wrong things. Like a coherent plot. Piccirilli is a lot of fun to read. There is always that central character who knows a bit more than those around him; whether it is more effective magical spells or just that so much of what is going on is bullshit. When Piccirilli brings more plotting into the mix, things tend to go wrong. The Deceased turns into little more that a pretty good horror movie, with girls, who I assume have large breasts, running around an old house during a thunderstorm. The gangster story that runs through Headstone City is not as resolved or effective as the weirdness that underlies it.

But these books are just the kind of fun I hoped modern horror novels could offer. They are literate, amusing, at times really icky, and never slow down. I understand that Piccirilli’s recent novels are more straightforward crime stories, so I hope he has worked out those plotting issues. On the off chance that anyone reading this might actually pick up a Piccirilli novel, I recommend starting with the best, A Choir of Ill Children. If nothing else, you will learn a really interesting new use of the word "vinegar."

GMRC Review: The Stochastic Man by Robert Silverberg

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s fourth GMRC review to feature in our blog.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s fourth GMRC review to feature in our blog.

Robert Silverberg considered The Stochastic Man a valedictory offering. When he wrote the novel in the early 1970’s he had already resolved to effect his second retirement from the world of science fiction. His first retirement came around 1958, the year the science fiction magazine world imploded due to over-saturation and the growing market for paperback books. Writer and editor Frederik Pohl brought Silverberg back into the sf fold in the early 1960’s, encouraging him to write more thoughtful material than the pulp-influenced novels and stories he cranked out–and Silverberg would not himself object to that characterization–during the previous decade. But then, by the 1970’s, Silverberg discovered that he was "on the wrong side of a revolution." He joined in with the new crowd of younger writers, J. G. Ballard, Thomas M. Disch, Samuel R. Delany and others, who were producing more literary and experimental fiction. ("Younger" is a relative term here. Silverberg himself was only in his thirties at this time, but he had been publishing since he was nineteen.) This period, from 1965 – 1974, is considered to be Silverberg’s best, but he saw his readership drying up.

"What was fun for the writers, though, turned out to be not so much fun for majority of the readers, who justifiably complained that if they wanted to read Joyce and Kafka they would go and read Joyce and Kafka. They didn’t want their sf to be Joycified or Kafkaized. So they stayed away from the new fiction in droves, and by 1972 the revolution was pretty well over."

Silverberg also cites the pernicious influence of Star Wars and the craze for trilogies on the popular sf market. He considered himself out of the game and simply fulfilling contractual commitments when he wrote The Stochastic Man and Shadrach in the Furnace, published in 1975 and 1976 respectively.

The Stochastic Man may not be the worst title ever given an sf novel, but forty years later it is unappealing, opaque, and dated. Silverberg gives a history and definition of the term in the opening chapter. It comes from logic and mathematics and figures in writing on computer theory. I associate it with the titles of text books and academic monographs filled with symbols and formulas I will never understand. On the practical level, it refers to using sophisticated sampling methods to gather a large enough pool of variables to proceed to an educated guess. Sexy stuff, right? In the 1970’s it must have had buzzword novelty. I ran it through Google’s NGram viewer that tracks a term’s popularity. "Stochastic" makes a steady climb from near total obscurity in 1950 to a high point in 1990 and then, after a period of stasis, there is a decline beginning at the turn of the century. In the 1970’s it was definitely on the rise. Silverberg’s novel takes place in the 1990’s, so when Lew Nichols defines himself as a stochastician, he is using a trendy 1970’s term to describe a profession that sounds very much like what we would call a consultant, no frills attached.

The 1970’s permeates Siverberg’s near future narrative. New York City at the turn of the millennium is the worst case scenario of what New York in the early 1970’s was becoming. With the successful Disneyfication of Times Square and the city’s declining crime rates it is hard to remember that forty years ago New York City was dirty, dangerous, and nearing bankruptcy. Silverberg and his wife were both lifelong New Yorkers, but they had, like many of their friends, decamped for the West Coast by the time he wrote this novel. In Lew Nichol’s New York City, Puerto Rican and Black populations stage pitched battles. Large portions of the city are too dangerous to enter, and those who can afford them travel with protective devices that ward off attackers. The nicest, newest and safest buildings are on Staten Island while the Upper East Side is livable but crumbling. All but the finest restaurants serve artificial food.

But Lew and his wife Sundara, a glamorous woman of Indian origin, live the good life. Lew’s stochastic firm brings in an enviable income, as does Sundara’s art gallery. (Hmm, a wealthy man whose wife runs an art gallery. Silverberg got that one right.) They attend exclusive parties where the elite mingle and choose sexual partners for later in the evening. A variety of legal drugs keep the party going.

"The terrors and traumas of New York City seemed indecently remote as we stood by our long crystalline window, staring into the wintry moonbright night and seeing only our own reflections, tall fairhaired man and slender dark woman, side by side, side by side, allies against the darkness… Actually neither of us found life in the city really burdensome. As members of the affluent minority we were isolated from much of the crazy stuff…"

So what is this novel actually about? Reviewers need not worry about spoilers, since a dozen pages into it Lew Nichols, as first-person narrator, has revealed most of the plot developments. Lew will become a consultant to the political campaign of the charismatic Paul Quinn, the great hope of a city and country seeking to rejuvenate itself, but who Lew describes as "potentially the most dangerous man in the world." He imagines that American voters dream of being able to withdraw the votes that as Lew is telling the story they will not place for another four or five years. And there is the enigmatic character of Martin Carvajal, a milquetoast multimillionaire who goes beyond Lew’s stochastic methods and is able to literally see the future. Lew calls him a "wild card in the flow of time." Carvajal’s resigned, passive nature comes from not only the fact that for him the future and history are one and the same, but he is also aware of the exact moment of his rapidly approaching violent death. He wants to bring Lew on as a pupil in seeing the future, rather than simply making educated guesses about it.

Revealing all in the first chapter of a book sets up a classic suspense structure where readers stay with the story to see how the inevitable works itself out. But Silverberg’s profoundly pessimistic novel is not about keeping you on the edge of your seat. By revealing so much early on, the reader becomes, like Carvajal and increasingly like Lew, one that can only watch inexorable events unspool like the frames of a film. More or less knowing what’s coming makes all the political machinations and messy personal relationships objects of detached interest rather than elements in an engaging plot. The Stochastic Man is a stylistic exercise that is likely to leave many readers cold, but I found it the most interesting though not the best Silverberg novel I have read.

Revealing all in the first chapter of a book sets up a classic suspense structure where readers stay with the story to see how the inevitable works itself out. But Silverberg’s profoundly pessimistic novel is not about keeping you on the edge of your seat. By revealing so much early on, the reader becomes, like Carvajal and increasingly like Lew, one that can only watch inexorable events unspool like the frames of a film. More or less knowing what’s coming makes all the political machinations and messy personal relationships objects of detached interest rather than elements in an engaging plot. The Stochastic Man is a stylistic exercise that is likely to leave many readers cold, but I found it the most interesting though not the best Silverberg novel I have read.

And what is this obsession with knowing the future beyond the ability to choose lottery numbers and hot stocks? Carvajal’s resignation and depression should clue Lew in on the fact that foreknowledge does nothing but make you a passive agent of the inevitable. But like 17th century Puritans struggling with the paradoxes of predestination and free will, Lew cannot let go of his obsession with seeing. (Silverberg italicizes the term throughout the book.) At the end of the novel–and this would be a spoiler except it too is described in the opening chapter–Lew has inherited Carvajal’s millions and used them to set up an institute to develop the talent for second sight in as many people as possible. He still thinks this is a meaningful project. I thought he hadn’t read his own book.

(Biographical information in this review comes from Silverberg’s Other Spaces Other Times.

Philip K. Dickathon: The Zap Gun

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd and we’ve invited him to contribute to our blog. This is the latest in Dee’s series of Philip K. Dick reviews that he started on his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. We’ll keep posting them until he runs out of reviews or gets tired of Philip K. Dick books.

I was about fifty pages into The Zap Gun when it hit me. This PKD novel is a sustained satire on a focused topic. Each chapter did not introduce new characters with no discernible link to those I had already met. The plot had not yet splintered into blind alleys and drug-induced hallucinations. And PKD’s writing seemed relaxed. It lacked the driven quality that can inform both his best and worst books. He was having fun with this one.

I was about fifty pages into The Zap Gun when it hit me. This PKD novel is a sustained satire on a focused topic. Each chapter did not introduce new characters with no discernible link to those I had already met. The plot had not yet splintered into blind alleys and drug-induced hallucinations. And PKD’s writing seemed relaxed. It lacked the driven quality that can inform both his best and worst books. He was having fun with this one.

The object of his satire is the cold war arms race. The novel, written in 1965, is set in 2004. Lars Powderdry, known as Mr. Lars to his adoring fans, is a fashion weapons designer, the best in West-bloc. (West-bloc is us, the good guys. The enemy is a Soviet controlled Peep-east.) Lars designs while in a drug-induced trance. His sketches are whisked off to labs for fabrication and testing. His Peep-east counterpart is a young woman named Lily Topchev.

There is a dirty secret behind all this high tech militarism. None of the weapons work, nor are they needed. Agreements between West-bloc and Peep-east have made such weaponry obsolete. Films of the weapons in use are simulations using robots and special effects. The sketches are "plowshared." They become the basis for household gadgets and toys. The masquerade is necessary to keep the masses, the "pursaps," happy. They want both the threat of annihilation and the comfort afforded by weapons to avoid it. But then alien satellites appear in Earth’s skies and begin abducting entire cities to serve as slave labor in the Sirius galaxy. Lars and Lily need to make a real weapon but fast.

PKD outdoes himself with neologisms and acronyms in The Zap Gun. The concept of plow sharing has real poetry to it. The society is divided between an elite group of "cogs" and a mass of "pursaps." Lars is a cog, and he hopes the term derives from cognoscenti. I thought he was worried it might imply he was merely a cog in a wheel, but he goes back to an early English usage where "to cog" was to cheat at dice. I was pronouncing "pursaps" in a way that suggested "poor saps," but Dick makes it clear he means "pure saps." Surly G. Febbs embodies Dick’s jaundiced view of the masses. He is a self-important, deluded pursap angered because an alien invasion is delaying his appointment to what he imagines is an important government post. Febbs is a master of neologisms, hyphenated nouns, and acronyms, and he looks with disdain on those pursaps who cannot stay abreast of the lingo. That will likely include the reader, who might have trouble remembering what MACH stands for or just what a concomody does. Acronym fever reaches new heights with the creation of the BOCFDUTCRBASEBFIN. Who knows what it stands for? Just say it with confidence.

How earth repels the invaders is handled cleverly and dispatched with quickly. There is always the sense that PKD might not care much about his own plots. Of the PKD novels I have known almost nothing of before opening to page one, The Zap Gun is among the most enjoyable. I read that PKD wrote it because a publisher requested a story with Zap Gun as the title. That could be true. He once expanded a novella into a novel because the publisher had cover art he really liked. But PKD does well by his arbitrary title. In one scene the weapons designers are discussing their basic uselessness, and Lars says of the pursaps, "All they really want is a Zap Gun." That throwaway line sums up the satire and the underlying anger in the book.

GMRC Review: Rocannon’s World by Ursula K. Le Guin

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s third GMRC review in our blog.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his blog series Philip K. Dickathon and The Horror! The Horror! He can also be found on his own blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com. This is Dee’s third GMRC review in our blog.

Rocannon’s World is Ursula K. LeGuin‘s first published novel and is the first of her novels I have read. I’ve always thought that if I read Le Guin I would read The Left Hand of Darkness, since it was the big prize winner and the one everyone read back in the 1970’s, during the years after it first appeared and Le Guin’s reputation was on the rise. But I was not reading SF at that time, so I had only minimal interest, and, even worse, the novel always came with the dreaded recommendation, "No, even if you don’t like science fiction you are going to love this book." So I never read anything and only now, with both a renewed interest in SF and a self-directed tour through those writers who have earned Grand Master Status from the Science Fiction Writers of America, am I discovering the pleasures of her prose and storytelling.

Having decided to dive in, I headed straight for Left Hand but saw that it was the fifth novel in something called The Hainish Cycle. I like to start at the beginning, and in the Le Guin omnibus edition I got from the library, Rocannon’s World was a tempting ninety pages long. I didn’t know until after I finished and enjoyed it that in fact there are two chronologies to the Hainish Cycle, the order written and the order in which the stories occur. I could have started anywhere, since in some cases a millennium passes between narratives, but I still like the idea to seeing how Le Guin’s writing and sense of her future world develops in the real time of her composition.

Ninety pages, but since I was reading a bargain omnibus edition they were longish pages. Rocannon is still a short novel, only 144 pages in its PB editions. But in those few pages, and in her first novel, Le Guin creates an small-scale epic, both a classic quest tale and a story that spans several generations.

On the planet Formalhaut II, as the advanced space lords refer to the novel’s local, the culture is medieval and, unusual for all the inhabited worlds they investigate, there are multiple HILF’s, Highly Intelligent Life Forms. In the prologue, Semley, child of an ancient family wedded to the Lord of Hallam, endures the fallen estate of her family — good name but short of wealth. In a culture where display of wealth assures rank she sets out to retrieve a magnificent jewel that has somehow left the family treasure and been traded back to the Clay People who mined it. Within the first dozen pages, Semley has left her home, recruited the aid of the charming Kirien people and journeyed to the altogether less engaging caves of the Clay People. That this journey is made on large flying cats is likely to be the first narrative hurdle for readers who like their SF harder than softer. The hints of hard SF occur when the Clay People enter the action. Grungy and unappealing as they are, they live in underground cavern’s equipped with electric light and railways.

When Star Lords investigate new planets with multiple HILF’s they choose a species most likely to accept the technological head starts that will prepare them to join the League of all Planets. The Clay People have won out on Formalhaut II. They even have a space ship, into which they bundle Semley for transport to the planet where her jewel now rests in a museum of interplanetary artifacts. There she catches the eye of Rocannon, an anthropologist employed by the League, and he easily arranges for the return of the jewel. (This was written in 1966, and I wonder when the controversies over the return of imperialist plunder from European museums began to take shape.)

Upon return to Formalhaut II, Semley understands the consequences of her journey. In Le Guin’s universe, FTL travel is only possible in unmanned spacecraft. Although Semley feels her trip has taken no more than a year, she returns to a home where her husband and mother-in-law have been dead for a decade and her children are grown. Her courageous and adventurous journey has secured her nothing more than a long, solitary life.

That took me almost as long to tell as it does Le Guin, but it sets up the story of Rocannon’s establishment decades later of a base of Formalhaut II. We learn of this base only as it is destroyed, along with Rocannon’s survey team and all the work they have done. The universe is in a constant state of war preparedness, but this attack seems to have been sabotage, the first signs of divisions within The League of All Planets. Rocannon, unable to communicate with his own people, learns from satellite surveys that the enemy has established a base in the still unexplored Southern Continent. He puts together his own plucky crew of various species and it is back onto the flying cats.

That took me almost as long to tell as it does Le Guin, but it sets up the story of Rocannon’s establishment decades later of a base of Formalhaut II. We learn of this base only as it is destroyed, along with Rocannon’s survey team and all the work they have done. The universe is in a constant state of war preparedness, but this attack seems to have been sabotage, the first signs of divisions within The League of All Planets. Rocannon, unable to communicate with his own people, learns from satellite surveys that the enemy has established a base in the still unexplored Southern Continent. He puts together his own plucky crew of various species and it is back onto the flying cats.

This is a quest adventure, that without Rocannon’s, or more properly, Le Guin’s eye for anthropological detail and interesting world building, would slide into adventure fantasy of a most ordinary sort. But the swiftness of her writing, the predicaments she creates for her believable multi-species characters, and also her willingness to kill off so many protagonists kept me wrapped up in a narrative that seemed much larger than its ninety pages. Before his departure, an aging Semley gives Rocannon her precious jewel, should he need it along the way. And so this absurd, medieval artifact remains as crucial to the story as the special body suit Rocannon has on hand that although it makes him appear naked allows him to survive fire and torture.

When men like Rocannon join the star service, they know they are abandoning anything resembling a normal life of family or human contact. They may age slowly and inexorably as they poke about the universe, but centuries will pass on earth. Although contacts with home can be accomplished with a device capable of instantaneous communication across 120 light years, they have volunteered to become exiles in the name of science. It’s the respect Le Guin feels for their choices and the fundamental loneliness of their existence that give the novel its emotional depth. And I liked the flying cats.

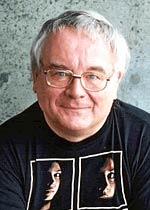

The Horror! The Horror! – Ramsey Campbell

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. This is a new series where Dee explores the darker side of genre fiction and it’s practitioners. Be sure to visit his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com for more genre goodness.

Ramsey Campbell‘s home page opens with a quote from the Oxford Companion to English Literature. It informs us that Campbell is "Britain’s most respected living horror writer."

Ramsey Campbell‘s home page opens with a quote from the Oxford Companion to English Literature. It informs us that Campbell is "Britain’s most respected living horror writer."

My copy of the OCEL is a fifth edition and has no entry for Campbell at all. If it did, that first statement might be followed by this bit of information: Charles Dee Mitchell has attempted to read five of Mr. Campbell’s works and only succeeded in finishing three. And trust me, in the case of those I abandoned it was not because I was too terrified to turn another page.

Ramsey Campbell may neither travel well nor date well. He has an American following but is a much bigger deal, obviously, in Great Britain. He is, after all, their most respected living horror writer. He has been publishing since the late 1950’s, and his most recent novel came out just this year from one of the presses that do high-priced, short runs of fantasy, horror, and science fiction titles. The books I tried were early to mid career novels. The Doll Who Ate His Mother (1976), The Face that Must Die (1979), The Nameless (1981), The Hungry Moon (1986), and The Influence (1988). Perhaps the past two decades have seen a remarkable transformation of his style and storytelling, but it is not as though the ones I read came un-recommended. The Face That Must Die was a somewhat fancy reprint with an introduction by Poppy Z. Brite and a few really bad illustrations. The Influence won the 1989 British Fantasy Award and is on the Guardian’s list of best sf and fantasy. The Hungry Moon, absolutely the worst of the lot, is the novel chosen by the Horror Writers Association to represent Campbell’s work.

Ramsey Campbell may neither travel well nor date well. He has an American following but is a much bigger deal, obviously, in Great Britain. He is, after all, their most respected living horror writer. He has been publishing since the late 1950’s, and his most recent novel came out just this year from one of the presses that do high-priced, short runs of fantasy, horror, and science fiction titles. The books I tried were early to mid career novels. The Doll Who Ate His Mother (1976), The Face that Must Die (1979), The Nameless (1981), The Hungry Moon (1986), and The Influence (1988). Perhaps the past two decades have seen a remarkable transformation of his style and storytelling, but it is not as though the ones I read came un-recommended. The Face That Must Die was a somewhat fancy reprint with an introduction by Poppy Z. Brite and a few really bad illustrations. The Influence won the 1989 British Fantasy Award and is on the Guardian’s list of best sf and fantasy. The Hungry Moon, absolutely the worst of the lot, is the novel chosen by the Horror Writers Association to represent Campbell’s work.

So is it just me? Of course, if that turned out to be the case, I would be the last person to admit it. I found the books mildly entertaining to unreadable. The thought that they might be genuinely frightening or even unnerving never crossed my mind.

So is it just me? Of course, if that turned out to be the case, I would be the last person to admit it. I found the books mildly entertaining to unreadable. The thought that they might be genuinely frightening or even unnerving never crossed my mind.

I’ll start with the ones I didn’t finish. The Hungry Moon is an overlong tale of Druid magic resurrected in the modern day by a religious nut. Campbell introduces us to too many of the residents of Moonwell, a village in Northern England. We learn what supposedly makes each one interesting and that takes a while. Then the event happens and we see how each of them react. Since I started skimming and finally quit the book, I don’t know the full panoply of horrible things that go on. But in the first chapter you learn that the village of Moonwell not only no longer exists but has been removed from maps, memories, and the telephone directory. The Influence concerns an evil great aunt out to possess the soul of her grandniece. If it had been a movie on TV and I could fast forward the commercials I would have watched it. But I couldn’t read it.

The other three novels are about psychopaths, two of them with some black magic references. The best of them is The Face that Must Die. The anti-hero, a Mr.Horridge, is a deranged young man obsessed with the evils of homosexuality. Great Britain decriminalized homosexuality in 1967, and decade later, Horridge sees the twisted results of the legislation everywhere he turns. He and his hammer will do what they can to remedy this situation. When the book first came out, portions were excised supposedly because they were too shocking. The complete text did not come out until 1982. Now the book just seems like fun. Horridge is crazy, and the block of flats on which he focuses his rage is peopled by characters only one of whom is gay and none of whom have any idea what’s coming. Like some of those old British stage thrillers, this is a shocker that now plays as black comedy.

The other three novels are about psychopaths, two of them with some black magic references. The best of them is The Face that Must Die. The anti-hero, a Mr.Horridge, is a deranged young man obsessed with the evils of homosexuality. Great Britain decriminalized homosexuality in 1967, and decade later, Horridge sees the twisted results of the legislation everywhere he turns. He and his hammer will do what they can to remedy this situation. When the book first came out, portions were excised supposedly because they were too shocking. The complete text did not come out until 1982. Now the book just seems like fun. Horridge is crazy, and the block of flats on which he focuses his rage is peopled by characters only one of whom is gay and none of whom have any idea what’s coming. Like some of those old British stage thrillers, this is a shocker that now plays as black comedy.

Campbell lives in Liverpool, and what he does best it create the down-in-the heel atmosphere and characters of that dismal, at least in his rendering, Northern England city. Everything is rundown, the weather is miserable, the people often not very bright. I especially liked the paranoid, pot-smoking hippie and the scatterbrained artist who lets a psychopath into her flat thinking he is the plumber.

So big deal, Mr. Campbell is not my cup of tea. If anyone, however, finishes The Influence, I am curious to know if anything even vaguely unpredictable happens by the time it is over.

The Horror! The Horror! – Poppy Z. Brite

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. This is the start of a new series where Dee explores the darker side of genre fiction and it’s practitioners. Be sure to visit his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com for more genre goodness.

This is not going to be a easy to write as I thought. I had my first line all planned out and can still use it:

This is not going to be a easy to write as I thought. I had my first line all planned out and can still use it:

"Of course her real name is not Poppy Z. Brite. It’s a pseudonym used by Melissa Ann Brite, born May 25, 1967 in New Orleans, Louisiana."

I got that much by glancing at Brite’s Wikipedia entry. But further down the page I picked up this bit of information: "Brite is a transgender man, born biologically female. He has written and talked much about his gender dysphoria/gender identity issues. He self-identifies with gay males, and as of August 2010, has begun the process of gender reassignment."

That I didn’t know, but it goes some ways towards explaining why almost all of Brite’s male characters, whether they are vampires, musicians, artists, drug dealers, or serial killers tend to be gay men.

When I decided to read some horror fiction, I thought I would start with Brite because I had heard the novels were good, moody, sexy, and very bloody. She, as I thought at the time, represented the new generation of horror writers, steeping the novels in a gothic punk atmosphere that no other writer at the time — the early 1990’s — had explored. Although she wrote stand alone novels, some characters and settings reappeared, creating a world of the supernatural and the grotesque that alternated between Missing Mile, North Carolina and New Orleans. (I love that name, Missing Mile.)

Brite’s horror publishing career lasted only half a decade and produced three novels and two volumes of short stories. His first novel, Lost Souls, he began while still a teenager. When his last horror novel, Exquisite Corpse came out in 1996, he was 29. Brite then turned to writing comic novels centered around the New Orleans restaurant scene. For the past several years, he as been on an official hiatus from writing at all. But I think with Lost Souls, Drawing Blood, and Exquisite Corpse Brite has left a significant legacy in the horror genre. (I have not read the short stories.)

Lost Souls is a lushly over-written, almost plotless tale of vampires traveling the country in what must be a very smelly van given their sloppy feeding habits. Their handsome leader, Zillah, keeps things somewhat under control with his more party-minded friends Molochai and Twig. They meet up with a confused, not yet out of the vampire closet fifteen-year old named Nothing. Nothing and Zillah almost instantly hit the sack. In a scene that involves killing his best friend, Nothing learns he is a vampire. Later he learns that Zillah, due to a one night stand in New Orleans many years ago, is his father, a fact that does not put a crimp in the sexual activity. They hang out in Missing Mile, NC, which is a much hipper place than it sounds. They seduce some people, they kill some people, they meet up with an old friend from New Orleans and relocate. There they get involved with some other kinky types — there’s no point in going any further with this. Brite’s enthusiastic prose keeps things happening if not exactly moving in any particular direction. It’s fun, although long.

Lost Souls is a lushly over-written, almost plotless tale of vampires traveling the country in what must be a very smelly van given their sloppy feeding habits. Their handsome leader, Zillah, keeps things somewhat under control with his more party-minded friends Molochai and Twig. They meet up with a confused, not yet out of the vampire closet fifteen-year old named Nothing. Nothing and Zillah almost instantly hit the sack. In a scene that involves killing his best friend, Nothing learns he is a vampire. Later he learns that Zillah, due to a one night stand in New Orleans many years ago, is his father, a fact that does not put a crimp in the sexual activity. They hang out in Missing Mile, NC, which is a much hipper place than it sounds. They seduce some people, they kill some people, they meet up with an old friend from New Orleans and relocate. There they get involved with some other kinky types — there’s no point in going any further with this. Brite’s enthusiastic prose keeps things happening if not exactly moving in any particular direction. It’s fun, although long.

Drawing Blood returns to Missing Mile where the sole survivor of a family massacre returns twenty years later to confront family ghosts. He meets up with a computer hacker on the run from the feds and guess what, they spend almost all their time in bed — or on the floor or in the shower. They are at the age when erections are so hard they ache. If the traditional horror audience of 16 to 25 year old males actually read this book, things have changed. Or maybe that demographic only applies to horror movies and not horror fiction. Drawing Blood is a haunted house story of sorts, with lots of rock and roll, gay sex, and mushroom ingestion. It is also a romance with a happy romance ending that I personally thought was out of place, but I suspect Brite, or at least his publishers, know their audience.

Drawing Blood returns to Missing Mile where the sole survivor of a family massacre returns twenty years later to confront family ghosts. He meets up with a computer hacker on the run from the feds and guess what, they spend almost all their time in bed — or on the floor or in the shower. They are at the age when erections are so hard they ache. If the traditional horror audience of 16 to 25 year old males actually read this book, things have changed. Or maybe that demographic only applies to horror movies and not horror fiction. Drawing Blood is a haunted house story of sorts, with lots of rock and roll, gay sex, and mushroom ingestion. It is also a romance with a happy romance ending that I personally thought was out of place, but I suspect Brite, or at least his publishers, know their audience.

And what to make of Exquisite Corpse? Brite says his original publishers turned it down because it was too extreme. They would have had a point. The descriptions of necrophilia, torture, and cannibalism are like nothing in the previous novels. The book has at least a couple of images that unfortunately will most likely always be with me. But her publishers might also rightly have considered this novel something of a mess. HIV and AIDS are prominent elements in the story, and perhaps the serial killers are meant to represent the death sentence the disease was considered at the time. This is Brite’s best writing. The grotesque sex is like the Marquis de Sade minus all the frou-frou. or Georges Baitaille without the pretension. What ever was intended, Exquisite Corpse might best be considered grand guignol fun. It is also a book I would never recommend to anybody I know, fearing recriminations.

And what to make of Exquisite Corpse? Brite says his original publishers turned it down because it was too extreme. They would have had a point. The descriptions of necrophilia, torture, and cannibalism are like nothing in the previous novels. The book has at least a couple of images that unfortunately will most likely always be with me. But her publishers might also rightly have considered this novel something of a mess. HIV and AIDS are prominent elements in the story, and perhaps the serial killers are meant to represent the death sentence the disease was considered at the time. This is Brite’s best writing. The grotesque sex is like the Marquis de Sade minus all the frou-frou. or Georges Baitaille without the pretension. What ever was intended, Exquisite Corpse might best be considered grand guignol fun. It is also a book I would never recommend to anybody I know, fearing recriminations.

Brite’s three novels are quickly becoming period pieces, and you have to find them squeezed onto the shelves surrounded by all the paranormal romance and zombie crap that dominates the field. I like to imagine some unsuspecting Laura K. Hamilton fan will pick up Exquisite Corpse and live to regret it.

Full Details

Full Details